The Background

Following the European withdrawal, statesmen ushering in independent Africa were faced with the dire prospect of addressing the many problems their colonial overlords had left upon them. Independent Africa was left in abject poverty with few political structures, many regional conflicts, and most importantly with artificial borders which placed little attention to genuine ethnic and linguistic linkages. States were united simply in facing the same uphill task of economic development.Theinternationalenvironment wasshapedbymajorwars between the European great powers, which had given way to the ideologically as well as geopolitically motivated Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union. Newly independent states were side-tracked from their own goals; competing alliances dominated their foreign policy and even played a role in shaping their internal politics. However, the end of the Cold War brought with it the establishment of the African Economic Community (AEC) in 1991 with the Abuja Treaty. It was fully implemented in May 1994.

The goal of the AEC was to harmonise both economic as well as human development across the board.It also sought to bring together fledgling regional economic communities (RECs), which were pursuing the same goal on a more micro level. The impetus for regional integration comes not only from the desire to pursue coordinated economic development, but to transcend the arbitrary boundaries by genuinely addressing the dispersion of ethnic and linguistic similarities across states. The last two decades have seen many of these sub-regional organisations reconstitute themselves into more functional institutions. The East African Community, originally conceived in 1967, was officially revived in July 2000. The current global economic environment has left Africa with little choice than to decisively consolidate and build its regional trading market. It is certainly the case that the commodity boom which has spurred Africa's much talked about economic growth will not continue forever and the benefits of the commodities' boom are only a small proportion of what the region could gain through an enlarged African market.

Africa in fact plays home to the world oldest surviving customs union: the South African Customs Union was established 1910, some 40 years before Europe's trade bloc. Yet despite this head-start, intra-African trade links are pitifully weak. The bulk of the region's trade is with Europe and America and only 12% with other African countries. By contrast 60% of Europe's trade is with its own continent; the same holds true for Asia.1

Intra-African trade today suffers from weak infrastructure. For African countries to actively utilise their abundant natural resources, it is imperative that they work together to develop an infrastructural capacity that is capable of harnessing these resources. Large scale infrastructure projects are prone to a large degree of corruption and having regional mechanisms of accountability can address this concern. Instituting criminal prosecutions at a regional level could introduce newfound efficiency at the state level. The same argument holds true for integrating other state institutions at the regional level to ensure that there is a larger degree of transparency and accountability.

The Two World Wars made it abundantly clear to European leaders that they needed to integrate and deliberately create mutual dependence in order to sustain peace. While Africa has had no shortage of conflicts, their cumulative effect does not seem to have created a strong enough political rational for Africans to feel the need to be integrated. Instead, African leaders have focussed on a purely economic rhetoric, highlighting regional integration as the means to overcome developmental challenges.2

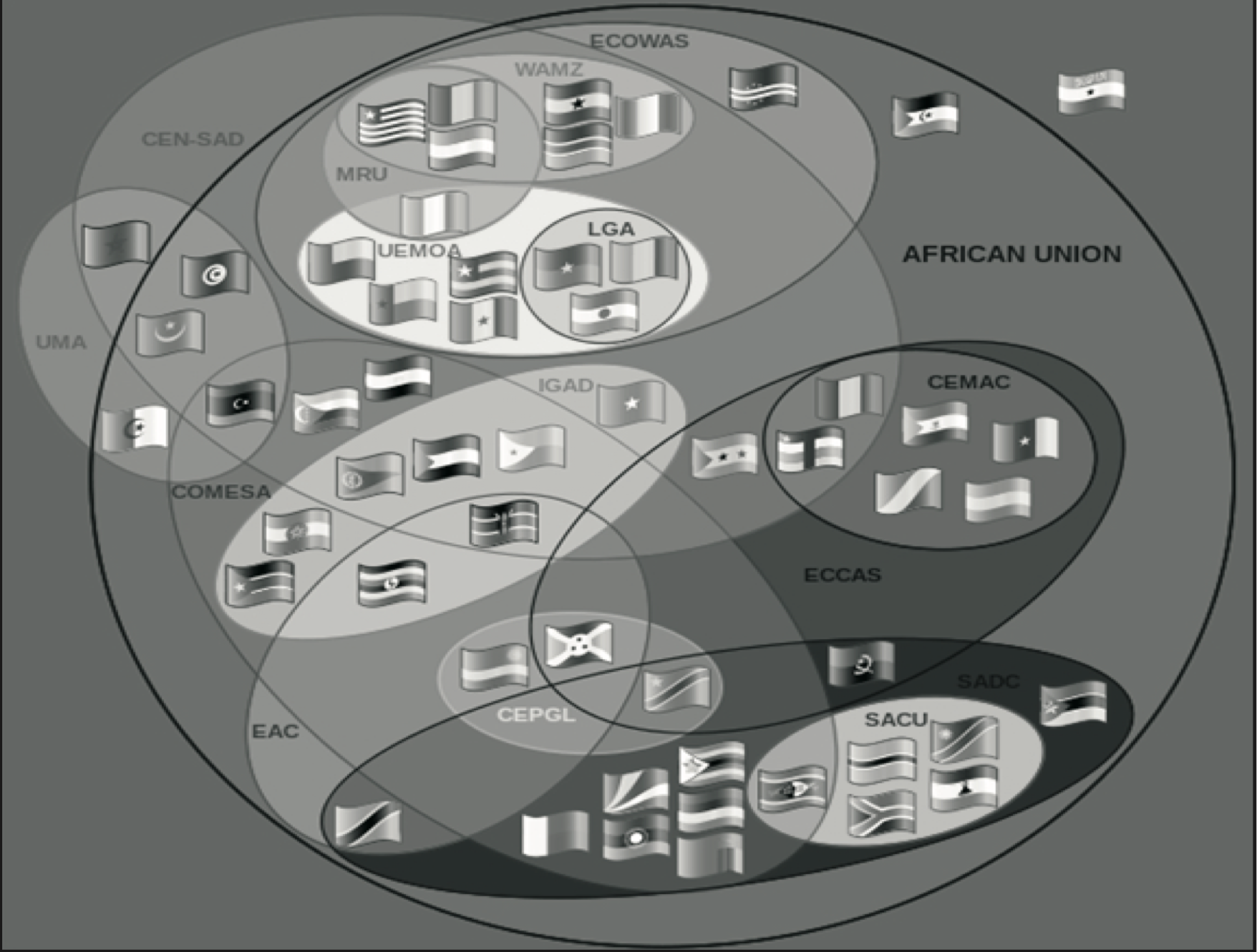

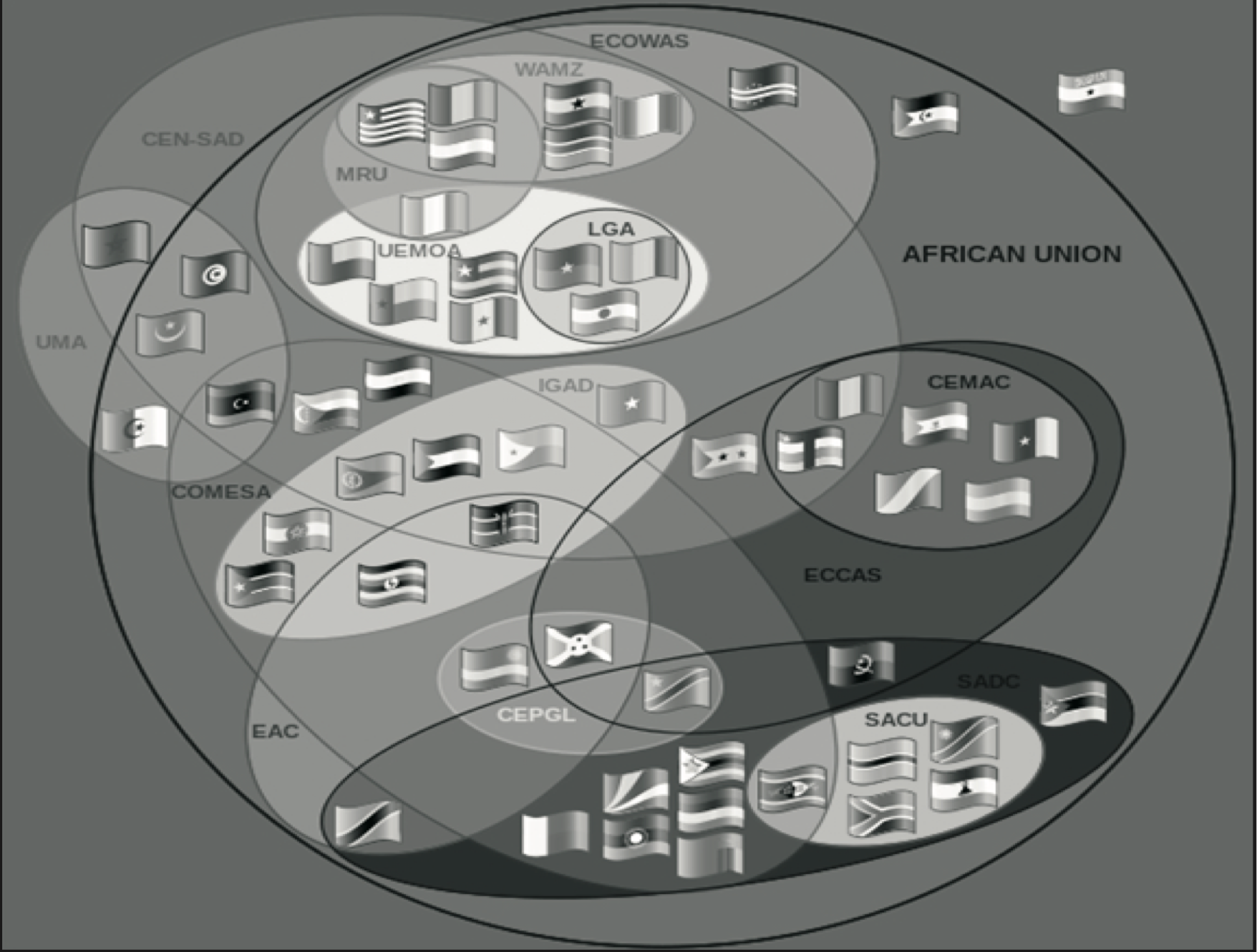

There are of course challenges facing African states from efficiently integrating; they have limited purchasing power and low technological capabilities. Perhaps the most significant of these challenges is that there is no 'lead goose'. The role played by the US in facilitating European integration with the Marshall Plan following World War II, was similarly assumed by Japan in South East Asia's experiment with integration.3 African countries have stronger colonial linkages rather than just Afro- ethnic or regional linkages, and this has hindered the regional integration process. While the African Union has attempted to play an all comprehensive role in this regard, it has however been unable to harmonise the integration process and has witnessed several different organisations emerge. Overlapping membership also is a key constraint in enabling genuine regional economic integration.

Out of the many different regional groupings operating in Africa, perhaps the most interesting is the East Africa Community. It was re- established with the primary objective to develop a single market and investment area for its member states, with the penultimate goal of achieving a political federation. Whereas many groupings have wished to undergo a similar level of economic integration, the desire to merge most state institutions at a supra-national level has not been implemented outside of this region.

This is of interest to Indian readers as India has maintained close ties with the region for centuries. There has been a historical exchange of commerce and ideology. Additionally, the adverse impact of colonisation in both India and Africa can be marginally alleviated by the fact that East Africa is now home to a large Indian diaspora. Following independence, the precursor to the African Union, the Organisation of African Unity was a full member of the India pioneered Non-Aligned Movement. The final section of this paper will address India's emerging partnership with East Africa.

The East African Community

Source: The Economist, <http://www.economist.com/node/14376512>

Understanding the East African Community

In a move reminiscent of the Benelux Agreement, which served as a precursor to European Integration, Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya established the EAC in July 2000. By 2005, the three countries had negotiated the terms of a Customs Union. Rwanda and Burundi joined the EAC in 2007 and were fully integrated into the East Africa Customs Union by 2009.4

The EACU, like many other similar blocs, works to further a common external trade policy by virtue of installing a common external tariff in respect to all goods imported into the partner states from foreign countries. In addition to this, the customs union removes non-tariff barriers to trade among the partner states along with customs duties and other charges. Its objective is to further liberalise intra-regional trade and enhance domestic, cross border, and foreign investment in the EAC. It also includes the introduction of common safety measures for regulating the import of goods such as phyto-sanitary requirements and food standards.5 The biggest aspect of a customs union therefore is that it turns five states into one contiguous market, which might have otherwise been proved to be too small to attract foreign investment.

One of the most sensitive talking points of customs union negotiations is establishing the protocol for the collection of duties and excise and the sharing of the collected revenue among member states. In the Southern African Customs Union all customs duties and excise which is collected in the common customs area is paid into the South African National Revenue Fund which is then shared with the member nations. Although it has been suggested that the EAC should work to establish a semi- autonomous regional revenue collecting body, it routinely holds top- level meetings of the commissioners from the revenue authorities in the member states.

There have been a total of 34 such meetings, with the most recent one being held on 10 May 2013. In 2011, the commissioners agreed to a scheme whereby duties and excise collected at the port of entry will serve the bond/guarantee to the transit country, while being payable at the country of destination. This is facilitated through an electronic tracking system, which will account for duty collection and revenue sharing. The scheme thus provides required security for national revenue authorities as well as reducing costs for traders in the region. However, the available information does not give an indication as to how the revenue will be proportioned among the member nations.6

EAC member nations are diverse in terms of incomes and social indicators. The EAC has a population of about 135 million, land area of 1.8 million square kilometres, and a nominal GDP of $84.7 billion dollars.7 Kenya has the largest economy with almost 41% of the total GDP, whereas Burundi is the poorest member with an average nominal per capita GDP of $180, less than a third of the EAC average.8 Regional integration is a way for the larger economies of the region such as Kenya, to enhance their own economic capacities, while at the same time encouraging and facilitating economic development of the poorer states, such as Burundi.

Although since the launch of the Customs Union, intra-EAC trade has grownfrom roughly $1.6 billion in 2006 to approximately $3.8 billion in 2010,thistrade hasbeenchieflydominatedbyprimaryproducts.Tea and coffee are produced and exported by Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania, whereas Uganda primarily exports vegetables, steel, maize, and tobacco. Kenya is the most sophisticated and developed economy in the region. Its exports include petroleum products, construction materials (limestone and cement), steel and other consumer oriented products such as soaps and polishes.9

In the face of globalisation and modern economics, integration is widely seen as a necessary way for countries to harness their true economic potential. This is only possible through widespread liberalisation of their economic structures. In order to have a more open economy, it is imperative to introduce a degree of competitiveness, which in turn would boost productivity. More competitive and productive economies are betterabletopenetrateglobalexportmarkets.Afreeflowing regional economy, as envisaged, will require a set of common banking laws and will also require common taxation of corporate income. Most importantly it will ensure that decisions at the national level that were formerlytaken keepinginmindthenationalinterest,willgivewayto decisions that will be taken at a regional level on perceived regional interest.10

While these arguments hold true for the entire continent, a study published by the World Trade Organization (WTO) on the regional integration process in Africa has argued that countries generally have efficient labour markets, well developed financial markets, and relatively sound economic institutions within the EAC. The study further maintains thatacrossAfricaitiseasiesttostartabusinessintheEAC, where the process takes the least amount of time, i.e. approximately 24.4 days and incurs the lowest costs. The study also finds that it is easiest to enforce contracts in the EAC, which can play a role in the ability of a firm to have greater access to lines of credit and to engage with new borrowers or customers.11

Amidst criticism that growth in Africa is riding on a commodity wave, all five EAC countries have attempted to diversify and solidify their economic bases. For example both Kenya and Tanzania have embraced the so-called mobile revolution. The on-going explosion in mobile technology has spurred innovations such as M-Pesa, the mobile money system, which allows users to make purchases and send cash-transfers from their cell phones. The information and communications sector in Kenya is growing at an average of 20% a year, and in 2010 it accounted for over 5% of the country's GDP.12 The telecommunications sector is of particular interest to India, with the Indian telecoms company Airtel already having 400 million customers in the African continent. The company has become the second largest operator in Kenya13 and holds a 39% stake in the Ugandan telecoms market.14 It maintains a large presence in Tanzania and entered the Rwandan market in 2012.15

As discussed earlier, the EAC has undertaken economic reforms to open up its economy to increase investment from abroad; the organisation has highlighted some key areas for investors. The EAC has opened the door to public-private partnership projects in the energy sector—highlighting the need for investment in geothermal, hydro and bio energy. It is also promoting investment in the water management sector, with both water harvesting and waste management being open to investment.16 The next section of the paper will address investment opportunities in infrastructure, which has been especially emphasised as an opportunity for foreign investment in the region.

In November 2011, the EAC organised the Lake Tanganyika Basin Development Conference and urged foreign investors to invest in Africa's longest and the world's second deepest lake. The lake's surrounding areas have over 20 million inhabitants, cradles a tremendous potential in hydroelectric power and is rich in mineral deposits. In addition to its agricultural use, the lake was touted to energy companies as potentially housing large reserves of oil or gas.17 As of June 2013, there are over 16 companies engaged in oil and gas exploration, which include Pan African Energy from the UK, Petrobras from Brazil and more importantly Motherland Industries Ltd. from India, which has been exploring the Malagarasi Basin.18 The Malagarasi River has the largest watershed of all the rivers flowing into Lake Tanganyika.

The next step for the EAC countries is the establishment of the East African Monetary Union which will culminate with the adoption of a single currency–the East African Shilling. A monetary union or currency union is considered a fundamental part of regional integration. It builds on the customs union by ensuring the member states utilise a common currency. The proposed currency was used in areas controlled by the British until 1969: the countries included Kenya, Tanganyika, Zanzibar, Uganda, Somalia, and Ethiopia.

The impetus towards a single currency is both political and economic. The European experience has shown that it can result in lower transaction costs for trade and investment. Adopting a single currency would require the creation of an EAC 'central bank', which would result in national governments being unable to print money to offset their debt. Decision making power would also see a shift from politicians to technocrats, which may result in increasing investor confidence. EAC member nations have intensified preparedness for the crucial harmonisation of monetary and exchange rate policies, payment and settlement systems, financial sector supervision, fiscal policies, and regionalisation of the financial sector to further the goal of a single financial market.19

However, a monetary union does not come without problems and a long term question mark over the prospect of an East African Shilling is the ability of its members to cope with a political or economic crisis.20 The European Debt Crisis exposed chasms amongst the different Euro zone economies; similarly, it is uncertain whether EAC member countries have ascertained a level of economic maturity to efficiently orchestrate a bailout.

Another potential problem with the adoption of a single currency is that violence in either Kenya or Tanzania would make life very difficult for the three landlocked members of the EAC. With only two major port cities—Mombasa in Kenya and Dar es Salaam in Tanzania—it is likely that instability or insecurity in either of these two countries would cause economic travails in the countries which rely on these ports for international trade. This opens the door to perhaps the focal point of integration efforts, the need to develop infrastructure in East Africa. All five nations bear enormous costs relating to transportation. The next section will make an indepth assessment of the needs, methods and challenges to infrastructural development in East Africa.

Infrastructure in East Africa

It is understood that the African continent is the richest in terms of resources, with vast reserves of diamonds, gold, important minerals as well as rich deposits of oil and gas. In order for African countries to harness these resources, it is imperative that they engage in infrastructural development. The lack of good quality infrastructure shows us why African countries are dogged by inordinately high operating costs. Road transportation offers a good illustration of this problem; exporters in the region face some of the highest transportation prices in the world. Recent statistics show that while it costs $4,000 to ship a container from Hong Kong to Mombasa, to haul the same from Mombasa to Burundi costs $10,000.21

Similarly, reports have shown that 47% of the cost of all of Rwanda's exports is related to transport overheads; one must understand that roads are too bad to enable efficient movement of goods and services, the ports are crowded and efforts to regionalise them for the benefit of the landlocked partners are still in contention.22 The difference between prices and operating costs is explained by the massive profit margins enjoyed by trucking companies in sub-Saharan Africa; many companies are able to charge hefty premiums thanks to regulations that prohibit would-be competitors from entering the trucking industry.23

A trans-national approach to infrastructural development may be met with some scepticism. Currently, private investors view multi-country projects as being even more risky than single-country projects. This means obtainingfinancecanbeaproblem.Kenya'sformerPresident Mwai Kibaki understood this problem and called on EAC member states to adopt public-private partnerships to finance infrastructure projects in the region. In the past, the region had opted for public sector investments, ignoring the private sector. For public-private partnership totakeroot,24 capitalmarketshavetobereformedandtherequiredlegal frame-work also has to be put in place. An added point is that, potentially, governments can serve as a check on each other; so while some sceptics may see a multi-country project as more risky, it can be argued that by introducing a regional commitment a greater degree of credibility is added to the scenario.25

One of the efforts taken by the EAC to improve infrastructure is a $300 million programme aimed at reducing the cost of doing business in the region by 40%. The project, run by Nairobi based Trade-Mark East Africa (TIMEA), involves automating ports, weighbridges, customs department and all other national agencies that manage the region's key transport corridors and border points.26 Another move has come in the shape of a regional shipper's council, a dedicated forum tasked with addressing the transport and logistics challenges in the region. Mr Richard Sezibera, secretary-general of the EAC has claimed that it is critical for the region to rehabilitate and expand the existing railway systems. According to him, less than five percent of cargo in East Africa is currently moved by rail. It is widely accepted that rail transport for goods is cheaper, competitive, and more efficient than road transport. Shifting a significant amount of cargo to railways will also guarantee longer life spans for newly constructed roads as well as those which have been recently repaired. It can also be seen as a more environmentally friendly way of transportation, as it can significantly reduce carbon emissions.27

Transportation via road is not just expensive, it is also time consuming. Studies have revealed that in the five days that it takes a truck to reach Kampala from Mombasa, 19 hours are spent to get clearance at borders and weighbridges. Tackling this “road block” had become a major issue for EAC legislators and in April 2013, following debate, two bills—the East African Community One Stop Border-Post Bill 2012 and the EAC Vehicle Load Control Bill—were taken up by the member states. Now, the clearance of goods and people across the EAC will be done through a single border transaction. Partner states have been assigned to implement the 'singular border processing arrangement' by setting up control zones at their respective border post. It is estimated that the reduction of only one hour spent at the border can save the region up to seven million dollars.28

Plans to develop the EAC's infrastructure go beyond the borders of the five member states. Rwanda's recent rapprochement with its vast ramshackle neighbour to the west, Congo, was made in the hope of increasing trade via the EAC's fledgling market. Congo's government seems willing to agree, and China, which is by some accounts the largest investor in the region, plainly wants Congo's timber, iron ore, and several minerals shipped across the Indian Ocean.29 It is for this and other reasons that Kenya has proposed to build a new deep sea port near the island of Lamu. The project is estimated to cost $25.5 billion, and will include the construction of a major highway, railway and oil pipeline to link up with the landlocked countries of South Sudan and Ethiopia. A consortium of companies led by China Communications Construction Company has won a $484 million contract to build the first three berths at the port. Through its flagship international arm, China Road and Bridge Corporation, China Communications signed a $66.7 million deal to expand the number of berths at Mombasa port, as well as a $2.66 billion deal to update Kenya's railways.30

Although on a smaller scale than China, India has attempted to enter both the hydrocarbon market and infrastructural development sector in East Africa. The Indian company RITES Ltd., which is a government of India enterprise, owns a 51% stake in Tanzania Railways Ltd. It has also collaborated with Kenya Railways to aid with locomotive operation and restructuring. With the emphasis being placed on developing the railway network across East Africa, this signals a prosperous future for this relationship. In June 2012, the Indian government committed $428,000 to the EAC, in what has been claimed to be the first direct assistance to be given to any regional community for a railway project. The project will be jointly coordinated by the African Development Bank and the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) and is aimed to modernise and improve the railways in the region. It is expected to be completed in 2014, and will hope to contribute to lowering transportation costs as well as enhancing trade in the region.31

South Sudan, following its independence, was invited by the governments of both Kenya and Rwanda to apply for membership to the EAC. This opens the door to another talking point in the EAC—the possibility o fexpanding its membership, not only to SouthSudan,but to other East African nations as well. Membership has become a bone of contention, both in terms of potential expansion and overlapping membership. Africa has 14 different RECs, eight of which are officially recognised by the EAC and six that are not. As shown earlier, East Africa plays host to both the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), in addition to the EAC. These issues will be addressed in the next section.

Expanding and Overlapping Membership

The EAC already has five nations with an approximate combined population of127millionpeople.Ifitexpands,itcouldaddasmanyas 120 million more to that number, making it more than twice as populous as Africa's 28 smallest countries combined. If defined by the area in which the 'lingua franca' of Swahili is used, east Africa spreads into Ethiopia and includes a chunk of Sudan, a swathe of east Congo, a strip of northern Mozambique and all of South Sudan.32 Charles Anyama, a

consultant working at the South Sudan Chamber of Commerce, has claimed that working with the EAC will help keep South Sudan's agricultural output competitive; here he is referring to the vast tracts of available arable land, which could give the country an opportunity to dominate the sector.33 If the EAC was to expand its membership to include the IGAD countries in the Horn of Africa, it may deem the latter organisation redundant. This could result in a greater degree of harmonisation.

Figure 1: The African Economic Community

In addition to Swahili, English is the de facto working language of all EAC member nations. This acts as an added benefit in the expansion rhetoric in the region. Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda were all formerly part of the British Empire, and Rwanda has made an effort to incorporate English into the primary education curriculum. English is the most widely spoken European language in Ethiopia.This is also the case in Somalia, which prior to independence was divided between British and Italian Somalilands. English is also the main working language of South Sudan.

The Africa Story: Unity or Split Loyalties?

|

Arab Maghreb Union+(UMA)

5 Members

|

Algeria, Morocco, Libya, Mauritania, Tunisia

|

|

Economic Community of West African States

15 Members

|

Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo

|

|

West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA)#8 Members

|

Benin, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Guinea Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo

|

|

West African Monetary Zone#

6 Members

|

Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone

|

|

Community of Sahel Saharan States (CEN-SAD)*

28 Members

|

Brukina Faso, Chad, Libya, Mali, Niger, Sudan, Central African Republic, Eritrea, Djibouti, Senegal, Egypt, Morocco, Nigeria, Somalia, Tunisia, Benin, Togo, Ivory Coast, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Comoros, Kenya, Mauritania, Sao Tome and Principe

|

|

Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa *

19 Members

|

Burundi, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Rwanda, Seychelles, Sudan, Swaziland, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe

|

|

East Africa Community

5 Members

|

Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania

|

|

Intergovernmental Authority on Development+(IGAD)

7 Members

|

Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya, South Sudan, Sudan, Djibouti, Uganda

|

|

Economic Community of the Great Lakes Countries (CEPGL)+

3 Members

|

Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda

|

|

Economic Community of Central African States

10 Members

|

Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Republic of Congo, Sao Tome and Principe

|

|

Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC)#

6 Members

|

Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Republic of Congo

|

|

Southern African Development Community

14 Members

|

Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Swaziland, Zambia, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Seychelles

|

|

Southern African Customs Union #

5 Members

|

South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, Swaziland

|

+ denotes inactive, in the case of the CEPGL efforts have been made to reactivate negotiations # denotes a subsidiary organisation to a larger Regional Economic Community

* denotes a Free Trade Area or a Trade Bloc as opposed to a Regional Economic Community

Overlapping membership has proved to be a major hurdle in African experiments with regional integration across the continent. The Euler diagram above illustrates the complex spaghetti bowl of African regional arrangements. This has resulted in a divergence of policy, in what should really be an exercise in the convergence of interests. Kenya is a major driving force behind the EAC, yet it is also part of IGAD, COMESA and Community of Sahel Saharan States (CEN-SAD), making it the only country in Africa, which is a part of four separate RECs. Tanzania is the only member nation of the EAC, which is a part of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

For some countries, overlapping membership in different RECs undermines binding commitments for different jurisdiction and policy environments whose mandates and objectives may not always be similar. Many Tanzanians are concerned that the EAC's political federation, which has been envisaged by the member nations, will affect their close relationship with several SADC countries.34

It is clearly not beneficial, and could in fact be problematic, to have multiple regional bodies serving the same purpose since these regimes may not necessarily have similar rules of engagement. It also flies in the face of the principles of efficiency that market integration seeks to achieve.35 Overlaps make it extremely difficult to integrate markets through common trade policy instruments such as a common external tariff.36 It is absurd to assume that a country can apply to two different tariffs by virtue of it being part of two separate unions.

Many argue that the recent commitments to establish a Free Trade Area (FTA) by the 26 member states of COMESA, EAC, and SADC is seen as an important step in addressing the problem of overlapping membership. It is believed that the tripartite FTA will be anchored on three pillars; market integration, infrastructural development, and industrialisation.37 Of the 26 countries in COMESA, EAC, and SADC, 17 are already in a customs union and are negotiating an alternative one to which they already belong, or are negotiating two separate customs unions.38 In fact, a more efficient way to harmonise efforts at regional integration is the AEC sponsored Continental Free Trade Area (CTFA). If this proposed agreement manages to move past deliberation and negotiation, it could enable the RECs to focus on other issues. For the EAC in particular, this would allow them to focus on working towards an East African Federation.

The EAC is the most advanced African REC in operation, in terms of both its holistic nature and the cohesiveness of its efforts. Of the eight RECs recognised by the AEC, only the SADC has achieved a higher rate of intra-trade growth. Intra-EAC trade grew from $1.81 billion in 2004 to $3.54 billion,39 whereas intra-SADC trade grew from 13.2 billion in 2000 to nearly 34 billion in 2011, representing an increase of about 155%.40 The SADC has 15 member countries compared to the EAC's five. Out of the 15 SADC members, only five are members of the Southern African Customs Union.

In terms of genuine advancement in regional integration, no other REC has moved at the same pace as the EAC. Both SADC and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) have made progress in building their free trade areas; however, they are lagging behind the EAC in launching a customs union.

Regional Economic Communities

|

Population

|

GDP

|

GDP

(per Capita)

|

GDP growth rate

|

Number of Members

|

|

EAC41

|

135 million

|

$84.7billion

|

$732

|

5.9%

|

5

|

|

ECCAS42

|

138million

|

$170billion

|

$1,231

|

4.3%

|

10

|

|

ECOWAS43

|

300million

|

$304.billion

|

$982

|

6.0%

|

15

|

|

SADC44

|

277million

|

$575.5billion

|

$1,999

|

5.1%

|

15

|

The Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) has launched an FTA, but it has faced varied degrees of problems in its implementation. However, its sub-group—the Economic and Monetary Community of Africa (CEMAC)—has succeeded in efforts to launch a singular currency, but to date it has not managed to achieve a customs union. The Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), the Community of Sahel- Saharan States (CEN-SAD) and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) are all moving slowly and are still in the early stages of negotiation. The AMU is virtually paralysed due to the Western Sahara dispute; it is no longer recognised by the AEC and there have been no meetings at the level of heads of state since 1994.45

Emerging Partners – East Africa and India

Supporters of COMESA and CFTA argue that a unified economic approach will help African nations have greater political clout for negotiating with emerging powers such as India, China, and Brazil. These partners have been hailed for three reasons. First, because of the basic mechanical effect of increased competition; when you multiply competitors, you lower transaction costs. The second is the experience that they bring; all these countries in addition to Turkey, South Korea, and Malaysia have managed to drag their populations into a middle income status. The relevance of their experience–be it in agriculture, low tech manufacturing or urbanisationis heldinhighregardbytheAfrican policy makers. Finally, these nations bring new financing mechanisms to the table in addition to newer markets for African products.46

Although Western countries have long had an entrenched economic presence across Africa, their relationship with the continent has predominantly been that of a donor anda recipient.The same however does not hold true for emerging powers; China's efforts at investing in Africa's infrastructure, as discussed earlier, still come in the form of a give and take relationship, where China benefits from Africa's mineral and hydrocarbon reserves. India'sinvolvementis more unique in nature.

As enumerated earlier, historical linkages as well as a post-independence ideological partnership enabled India to have a more holistic relationship with East Africa. India is by no means a new player in the region. India's flagship programme to engage with the developing world is the Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation (ITEC). The ITEC programme offered many African countries technical and economic assistance in a wide variety of fields including agriculture, hydrology, management, and information technology.

In terms of trade, India benefits from a large trade balance in its favour. All five EAC member nations import more from India than they export. In 2012 India's exports to Kenya were valued at approximately $3.7 billion; India's imports on the other hand were valued at only $100 million. Bilateral trade has also shown positive trends. India's total trade with Kenya grew from $1.4 billion in 2009 to $3.8 billion in 2012; similarly bilateral trade between Tanzania and India grew from $1.2 billion to $2.8 billion in the same time period.47 India is also one the largest trading partners in the region. It is the third largest trading partner of Kenya, the fourth of Uganda, and the second largest of Tanzania.48

Kenya's capital Nairobi is home to many Indian businesses, and some words from Indian languages have been adopted into Swahili. India's relationship with East Africa is on two levels. One is at a bilateral level whereby India has sought to form a genuine partnership with these countries. For example, India wrote off $5.236 million of government credit and interest to Uganda due to it being one of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) in 2002. India has also established several lines of credit allowing for the flow of millions of dollars through the EXIM Bank of India to boost trade with Kenya. It is also noteworthy that according to the Tanzanian government, over 118 companies with an 'Indian interest' have invested a total of $825 million in the country.49

India has also given direct aid in the shape of 100 water pumps to Uganda and The Energy & Resources Institute (TERI) has worked with the World Bank and the Ugandan government to establish four biomass producing plants to bring about rural electrification. In 2009 only 2% of Uganda's countryside had access to electricity. In the hydrocarbon market, Indian corporation Essar Energy Overseas Ltd. acquired a 50% stake in a Mombasa refinery in 2009. The refinery's products are not only sold in Kenya's domestic market but have enabled exports to Tanzania, Burundi, and Rwanda.50

Another avenue in which India has a large role to play is the pharmaceuticals industry. The recent verdict given against Novartis International in India's Supreme Court was celebrated across Africa, as a victory for the generic drugs industry. India is the largest supplier of pharmaceuticals to Uganda and its total pharma-exports to Africa are worth more than $8 billion.51 Many African countries are big beneficiaries of the cheaper generic drugs industry and India being a world leader has much to gain. Besides holding strong bilateral ties with the east African nations, India has attempted to mould a relationship with the EAC as an institution.

The Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), in association with the High Commission of India in Tanzania, organised “The India Show” to promote Indian industries' presence in the region. The event, held in Tanzania from the 25th to 27th of September 2013, hoped to attract business visitors from Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda as well. The visitor profile included CEOs, media officials, and technical experts in addition to a ministerial and trade delegation from India. In addition to the pharmaceuticals, energy, and infrastructure sectors, other focus sectors, including agriculture, construction, consumer durables, education, health care, textiles, and water management were identified for the show.52

Cooperation in the education sector can serve to cultivate a more holistic relationship between India and Africa. Indian universities are holding workshops in East African Capitals for potential students and advertising opportunities offered in their colleges. India's High Commissioner to Kenya believes that the use of English as a medium of communication in Indian educational institutions is one reason why India is a popular destination for African students. Indian universities are also considerably more affordable than their western counterparts. Some Indian universities are helping to arrange visas for recruited students, making the entire process easier.53 Additionally, there are several international scholarships that are open to students and some that are specifically directed towards Africa.

A Memorandum of Understanding between India and the EAC was signed on 28 April 2003; this was prior to Rwanda and Burundi becoming members. The following areas were identified for cooperation: railways, energy, agriculture, capacity building, tourism, and the possibility of a trade and investment framework agreement.54 There has also been a proposal for an India-EAC summit, with India's current High Commissioner in Tanzania being concurrently accredited to the EAC, whose legislative assembly is housed in Arusha—a major city in northern Tanzania—thereby the de facto capital of the REC.

Concluding Remarks – Towards Deeper Integration

There are several reasons why regional integration efforts in East Africa should be celebrated. When compared with Africa's other RECs, the EAC appears to be far more cohesive and advanced. As shown earlier, out of the eight recognised RECs in Africa, only the SADC, ECOWAS, ECCAS, and the EAC have managed to progress further than the initial stages of negotiation into something concrete. Its cohesion is best understood when contrasted against the aforementioned RECs. The SADC, ECCAS, and ECOWAS nations, in their efforts to further the integration process, have seen a number states withdraw from various operations. As mentioned earlier, the SADC has a membership of 15 states; however, the SACU only has a membership of five states. Similarly, ECOWAS has 15 member states although its monetary union has only eight members.

The EAC has also established a Food Security Action Plan to fight hunger and malnutrition in the region. The EAC single passport is in force and allows multiple entries to citizens of partner states to travel freely within the EAC region for up to six months. This has predominantly been issued to ease border crossing in the region. The single passport does not entitle its holder to work in any partner state, but the same right is extended to citizens of EAC member states through the EAC Common Market Protocol. This move was enacted in 2010, and Tanzania is currently the only country not to have completely opened up its doors to professionals, technicians, and trade workers. The country hopes to achieve this by 2015.55

In their efforts to improve infrastructure, the EAC has developed East Africa Road Network Project, in particular the Northern Corridor which connects the Kenyan port of Mombasa to Katuna, a town in Uganda, near the Rwandan border. In addition the project has included the development of the Dar-es-Salaam to Mutukula, Uganda–Central Corridor.

EAC partner states have also agreed to develop a framework for mutually recognising professional qualifications; for example, it is possible for legal practitioners to operate in any EAC country, without having to sit for new bar examinations. The effort to better harmonise education standards was facilitated by the establishment of the East African National Examination Council, which worked not only to standardise education quality but has been instrumental in the opening of the University of East Africa. The university maintains campuses in three EAC member nations.

In 1998, the EAC's then three member states exchanged their national curricula for review, with the aim of harmonising the same across the region.

The EAC then commenced a project to achieve the harmonisation of national curricula, which was divided into four phases; the first being a regional study undertaken to assess the state of curricular content, education structures, and legal frameworks in the member nations. The second phase moved to examine the study and approaches of delivering teacher training in the partner states with a view to identify gaps/overlaps in the areas to be harmonised. The study was completed in November 2009 and has since moved into phases three and four. The third phase is aimed at developing a relevant curriculum based on the recommendations of the study and the fourth and final phase is the implementation of the harmonised curricula. In 2009 it was announced that after a period of five years the EAC would be on track to complete this project.56

The five EAC nations have also established an EAC Health and Scientific Conference which will work towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals for maternal and child health, as well as improving the quality of healthcare in the region.57 On 3 December 2012 the EAC's headquarters were visited by the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation, which is a public-private global partnership committed to increasing access to immunisation in poorer regions of the world. GAVI has already announced that it plans to fund a Ugandan programme which will provide free vaccinations for pneumonia in the country—the disease is the largest cause of child deaths under 5 years of age.58

In addition to the Health and Scientific Conference, the EAC has also worked to establish a regional information exchange system, which has two projects; first, the East African Public Health Laboratory Networking Project which aims to open 25 satellite labs across the region, which will aim to enhance diagnostic capabilities in the region to provide a better understanding of both communicable and non- communicable diseases. The second project is the East African Integrated Disease Surveillance Network, which aims to harmonise disease surveillance systems in the region and is supported financially by the Rockefeller Foundation. Finally, the EAC also has a Medicines and Food Safety Unit which aims at providing quicker access to affordable essential medications. This is supported by the World Bank.

As the EAC moves forward with its integration process, it is imperative that the organisation improves its measures for fiscal and political scrutiny. As stated earlier, one of the barriers to deepening integration in the region has been the divergent forms of governance. There is an urgent need to ensure better accountability and transparency, particularly in Yoweri Musuveni's Uganda, where allegations of corruption have continuously plagued the legitimacy of the government. Such measures will thereby hope to make sure that financial misdirection is curtailed. The EAC appointed an observer mission to watch over Rwanda's September 16 elections. The role of the mission was to scrutinise the election and a mission report is expected to detail how the electoral process in Rwanda in particular and East Africa in general can be made more free and fair.60

It is also important for the EAC to strengthen the rule of law and increase the access to justice in its member nations. Although the East African Court of Justice(EACJ) has been in operation since July 2000, it serves only as a platform for member states to put pressure on each other. Provisionally the court is mandated to allow individual legal practitioners in any member state to challenge the legality of an act or a regulation; however, the functionality of this provision has been called into question. One suggestion is that EACJ function as the apex court in the region with suzerainty over its member state's courts of justice. This may result in improving the functionality of legal systems within member nations.

In a report identifying the existing barriers to trade in the region, the East Africa Business Council has made some recommendations to the EAC. They argue that certain districts in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda are invoking an old act, which mandates local councils to levy fees. This act restricts such fees to goods produced locally and not transit cargo. However,there havebeenincreasedreportsofbriberyandextortion against the local councils.61 It has therefore been recommended that the EAC move to abolish fees on transit cargo within the region.

It is clear that legislators in East Africa have made major efforts at achieving regional harmony, with the EAC having stated that it hopes to be a middle-income economy region by 2020.Their efforts must be seen as crucial to furthering that goal.

The progress that has been made over the last decade has laid a strong foundation for deepening regional integration and preparations for the establishment of a complete political federation continue. It is likely that the five nations will soon be joined by South Sudan. With the prospects of expanding membership, and the increasing size of the potential market, it is integral for emerging global heavyweights such as China and India to be fully committed to furthering the process. Support from such partners will aid efforts to integrate and thereby enable a more profitable relationship between East Africa and themselves.

Endnotes

-

“Intra-African Trade: The Road Less Travelled”, The Economist, April 17, 2013. <http://www.economist.com/blogs/baobab/2013/04/intra-african-trade>

-

Dirk Reiner Mann, “Are Lessons From European Integration Relevant For Africa”, World Bank Blog, September 28, 2010 <http://blogs.worldbank.org/ africacan/are-lessons-from-european-integration-relevant-for-africa>

-

“African Integration Is Great But It Has Its Hurdles”, New Vision Uganda, May 26, 2010 <http://www.newvision.co.ug/D/8/20/720784>

-

The East Africa Community, “History Of The EAC: Milestones In The EAC Integration Process” <http://www.eac.int/index.php?option= com_content&view=article&id=44&Itemid=54&limitstart=1>

-

East Africa Community Secretariat, “Protocol On The Establishment Of The East African Customs Union”, March 2, 2004, pg 12, 33 <http://www.eac.int/ index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=154&Itemid=148>

-

“East African Community: New Duty Collection & Revenue Collection Scheme In The EAC”, Trade Watch, Vol 10, No , Ernst & Young, March 2011, pg 33 <http://tmagazine.ey.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/7130932.pdf>

-

The East Africa Community, “EAC Quick Facts” <http://www.eac.int/ index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=169&Itemid=157>

-

Catherine McAuliffe, SwetaSaxena, MasafumiYabara, “Sustaining Growth In The East Africa Community”, in The East Africa Community After Ten Years: Deepening Integration, ed. Hamid R. Davoodi, The International Monetary Fund, 2012, pg 18 <http://www.imf.org/external/np/afr/2012/121712.pdf>

-

Pearl Thandrayan, “The EAC: Regional Engine, African Model”, World Politics Review, February 20 , 2013, pg 4 <http://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/ articles/12733/the-eac-regional-engine-african-model>

-

“Regional Integration in East Africa: What's Next?”, Trade Mark East Africa, October, 12, 2012 <http://www.trademarkea.com/regional-integration-in-east- africa-whats-next/>

-

Trudy Hartzenberg, “Regional Integration in Africa”, World Trade Organization, October 2011, pg 15 <http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/ ersd201114_e.pdf>

-

ShantayananDevarajan, Wolfgang Fengler, “Africa's Economic Boom”, Foreign Affairs, pg 4 <http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/139109/shantayanan- devarajan-and-wolfgang-fengler/africas-economic-boom?page=show>

-

“Africa-Kenya Grows Subscriber Base To Four Million”, TeleGeography, January 14, 2011<http://www.telegeography.com/products/commsupdate/articles/ 2011/01/14/airtel-kenya-grows-subscriber-base-to-four-million-3g-network-to- launch-in-march/>

-

“Airtel Signs Definitive Agreement To Acquire Warid Uganda”, Airtel, April 23, 2013 <http://www.africa.airtel.com/wps/wcm/connect/africaairtel/uganda/ home/about_us/press_release/april_23_2013>

-

“Airtel Launches Mobile Services In Rwanda”, The Economic Times, March 30, 2012 <http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2012-03-30/ news/31260864_1_joint-md-manoj-kohli-bharti-airtel-ceo-zain>

-

“EAC, Tripartite Partners In Conference To Drive Regional Infrastructure Development”, The East African Community, October 23, 2010 <http://www.infrastructure.eac.int/index.php?option=com_content&view=artic le&id=134:tripartite-igad-infrastructure-conference&catid= 40:press&Itemid=149>

-

“Come Invest In Lake Tanganyika Basin – President Nkuruziza”, The East Africa Community, November 28, 2011 <http://www.invest.eac.int/ index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=121:come-invest-president- nkurunziza&catid=40:press&Itemid=122>

-

Orton Kishweko, “Tanga Most Likely To Join Gas, Oil Producers Club Soon”, Daily News Tanzania, June 23, 2013 <http://dailynews.co.tz/index.php/local- news/18982-tanga-most-likely-to-join-gas-oil-producers-club-soon>

-

McAullife, Saxena, Yabara, “Sustaining Growth in the East Africa Community”, pg 19 <http://www.imf.org/external/np/afr/2012/121712.pdf>

-

Avi Bram, “The Road Ahead For The East African Shilling”, Think Africa Press, July 8, 2011 <http://thinkafricapress.com/economy/road-ahead-east-african-shilling>

-

“EAC Sets Up Regional Shippers Council”, Trademark East Africa, May 8, 2013 <http://www.trademarkea.com/eac-sets-up-regional-shippers-council/>

-

Kenneth Agutamba, “High Operating Costs Still Dog Business In EAC”, Rwanda Focus–AllAfrica.com, May 5, 2013 <http://allafrica.com/stories/ 201305070962.html>

-

Devarajan, Fengler, “Africa's Economic Boom”, pg 6 <http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/139109/shantayanan-devarajan-and- wolfgang-fengler/africas-economic-boom?page=show>

-

“Novelty Needed To Fund EAC Infrastructure”, Capital FM Business, November 29, 2012 <http://www.capitalfm.co.ke/business/2012/11/novelty-needed-to- fund-ea-infrastructure-kibaki/>

-

Paul Collier, “Emerging East Africa: Achievements and Goals Of The East Africa Community”, in The East Africa Community After Ten Years: Deepening Integration, ed. Hamid R. Davoodi, The International Monetary Fund, 2012, pg 14 <http://www.imf.org/external/np/afr/2012/121712.pdf>

-

George Omondi, “EAC Begins Race To Grow Trade With New Partners”, The Business Daily – Africa, February 2, 2011 <http://www.businessdailyafrica.com/Corporate-News/EAC-begins-race-to-grow-trade-with-new-partners/-/539550/1099756/-/l3cyns/-/index.html>

-

“EAC Sets Up Regional Shippers Council”, Trade Mark East Africa <http://www.trademarkea.com/eac-sets-up-regional-shippers-council/>

-

Peter Kiragu, “EAC Initiates Laws To Ease Border Crossing”, The Star – Kenya, April 12, 2013 <http://www.the-star.co.ke/news/article-116433/eac-initiates- laws-ease-border-crossing>

-

“An East African Federation: Big Ambitions, Big Question-Marks”, The Economist, September 3, 2009 <http://www.economist.com/node/14376512>

-

DrazenJorgic, “Kenya Says Chinese Firm Wins First Tender For Lamu Port Project”, Reuters, April 11, 2013 <http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/04/11/kenya- port-lamu-idUSL5N0CX38D20130411>

-

NEPAD-IPP Facility & Indian Trust Fund Join Forces To Enhance Railway Sector In EAC Region, New Partnership For Africa's Development, <http://www.nepad.org/regionalintegrationandinfrastructure/news/2741/nepad -ipp-facility-and-indian-trust-fund-join-forces->

-

“An East African Federation: Big Ambitions, Big Question-Marks”, The Economist <http://www.economist.com/node/14376512>

-

Simon Allison, “South-Sudan's Oil For Food Gambit”, Think Africa Press, February 6, 2013 <http://thinkafricapress.com/south-sudan/oil-food-gambit- eac>

-

“Assessing Regional Integration in Africa – V”, United Nations Economic Commission For Africa, UNECA Documents Publishing Unit, 2012, pg 78 <http://uneca.africa-devnet.org/files/uneca_aria_v_june_2012.pdf>

-

Mark Mngomezulu, “Applying Sense To Regional Integration”, International Political Forum, April 25, 2013 <http://internationalpoliticalforum.com/africa- regional-integration/>

-

“Assessing Regional Integration in Africa – V”, United Nations Economic Commission For Africa, pg 77 <http://uneca.africa-devnet.org/files/ uneca_aria_v_june_2012.pdf>

-

Hartzenberg, “Regional Integration in Africa”, World Trade Organisation, pg 7 <http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/ersd201114_e.pdf>

-

“Assessing Regional Integration in Africa – V ”, United Nations Economic Commission For Africa, pg 1 <http://uneca.africa-devnet.org/files/ uneca_aria_v_june_2012.pdf>

-

Augustus Muluvi, Paul Kamau, Simon Githuku and Moses Ikiara, “Kenya's Trade Within The East Africa Community”, in Accelerating Growth Through Improved Intra-African Trade, Brookings Institution, January 2012, pg 20 <http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/reports/2012/1/intra%20 african%20trade/01_intra_african_trade_full_report.pdf>

-

Southern African Development Community, “Impact of Free Trade Area” <http://www.sadc.int/about-sadc/integration-milestones/free-trade-area/>

-

<http://www.statistics.eac.int/index.php?option=com_content&view= article&id=141&Itemid=111

-

<http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/FIELD/Dakar/ pdf/RECProfileECCAS_ENG.pdf, http://www.ceeac-eccas.org/ index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2&Itemid=2

-

<http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/FIELD/Dakar/ pdf/RECProfileECOWAS_ENG.pdf

-

<http://www.sadc.int/about-sadc/overview/sadc-facts-figures

-

AtenioNdomo, “Regional Economic Communities in Africa: A Progress Overview”, GesellschaftfürTechnischeZusammenarbeit (GTZ), May 2009, pg 26 <http://www2.gtz.de/wbf/4tDx9kw63gma/RECs_Final_Report.pdf>

-

Nicholas Norbrook, Marshall Van Valen, “Africa's Emerging Partners: Friend or Foe”, The Africa Report, May 30, 2011 <http://www.theafricareport.com/News- Analysis/africas-emerging-partners-friend-or-foe.html>

-

“Bilateral Trade Statistics”, Export Import Data Bank, Department of Commerce, June 6, 2013

48. “Trade Statistics”, European Commission

-

- Kenya-EU Bilateral Trade And Trade With The World <http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/september/tradoc_113407.pdf

-

- Uganda-EU Bilateral Trade And Trade With The World <http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2011/january/tradoc_147417.pdf>

-

- Tanzania-EU Bilateral Trade And Trade With The World <http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2011/january/tradoc_147401.pdf>

-

SanjuktaBanerji Bhattacharya, “India-East Africa Ties: Future Trajectories”, Africa Quarterly, Vol 49, No. 1, February – April 2009, pg 22 <http://www.indiaafricaconnect.in/upload/newsletter/May2008- October2009.pdf>

-

Bhattacharya, “India-East Africa Ties: Future Trajectories”, Africa Quarterly, pg 22 <http://www.indiaafricaconnect.in/upload/newsletter/May2008- October2009.pdf>

-

Bhattacharya, “India-East Africa Ties: Future Trajectories”, Africa Quarterly, pg 22 <http://www.indiaafricaconnect.in/upload/newsletter/May2008- October2009.pdf>

-

“The India Show”, Confederation of Indian Industry <http://www.indiashowtanzania.com/pdf/e_brochure.pdf>

-

“Indian Universities Race to Attract East African Students”, The Times of India, <http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/education/news/Indian-universities- race-to-attract-East-African-students/articleshow/21782122.cms>

-

“The East Africa Community”, Ministry of External Affairs India, April 2011<http://mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/east-african-community-april- 2011.pdf>

-

The East Africa Community – Common Market, “Annex On The Free Movement of Labour/Workers” <http://www.eac.int/commonmarket/movement-of- labour.html>

-

The East Africa Community –Education, “Harmonization of Education & Training Curricula in East Africa” <http://www.education.eac.int/ index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=53&Itemid=106>

-

“East Africa Community Seeks To Strengthen Cooperation On Health”, Daily News Tanzania, March 26, 2013 <http://www.dailynews.co.tz/index.php/local- news/15846-east-africa-community-seeks-to-strengthen-cooperation-on-health>

-

“Uganda Government Announces Free Pneumonia Vaccination”, In2EastAfrica, November 30, 2012 <http://in2eastafrica.net/uganda-govt-announces-free- pneumonia-vaccination/>

-

The East Africa Community – Health,“ The East African Community Health Sector: Medicines and Food Safety” <http://www.health.eac.int/ index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=142&Itemid=161>

-

“EAC to Send Observer Mission for Parliamentary Elections”, News of Rwanda, September 11th 2013 <http://www.newsofrwanda.com/english/20407/eac-to- send-observer-mission-for-parliamentary-elections/>

-

“Current Barriers to Trade Within the East Africa Community”, East Africa BusinessCouncil <http://eabc.info/current-trade-barriers/>

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV