Introduction

The India-Latin America relationship has been infused with new life in the recent years. India’s External Affairs Minister (EAM) S Jaishankar has visited four Latin American and Caribbean countries since September 2019, and is visiting four more in April 2023. The last Indian EAM to visit the region was Yashwant Sinha, who went to Brazil in 2003, when BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) was being conceptualised. Since becoming EAM, Jaishankar has shown the political will—largely absent in his predecessors—to improve India’s relations with the countries of Latin America.

Jaishankar has also sought to underscore the region’s importance at home in New Delhi. At a February 2023 conference on India-Latin America relations in New Delhi, Jaishankar described his prognosis of India’s relations with the region as “hopeful and optimistic.” He emphasised that Latin America forms part of India’s larger goal of “becoming a leading global power,” adding that India must develop a footprint in the region with “relationships that really count, with investments of substance and cooperation that is really noteworthy.”[1] In April 2023, Jaishankar is visiting Guyana, Panama,[a] Colombia and the Dominican Republic—none of which has previously seen a bilateral visit by an Indian foreign minister.

The timing of these overtures could not be any better, as India and Latin America have become more economically relevant to each other in recent years. Trade was at an all-time high of US$50 billion in 2022, just a pinch higher than the previous peak of US$49 billion in 2014.[2] This is despite the minimal India-Venezuela trade of only US$414 million in 2022, which had previously reached US$15 billion in 2013,[3] consisting nearly entirely of Venezuelan oil exports to India. Venezuela has been out of the picture since 2020 due to US secondary sanctions on the country’s national oil company, Petroleos de Venezuela.[4]

Overall, however, if Latin America were a country, it would be India’s fifth largest trade partner in 2022-23,[5] after the United States (US), China, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia. The increase in bilateral trade, of 17 percent from US$42.6 billion in 2021, can be attributed to the following:

- India-Brazil trade: In 2022, India-Brazil trade peaked at US$16.4 billion, consisting primarily of the oil trade (of Brazilian exports of crude oil and India’s exports of refined petroleum), edible vegetable oils, automobiles, pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals.[6] India’s exports to Brazil in 2022-23[7] surpassed those to Germany, Australia, South Korea or Indonesia—which are among India’s biggest export partners. Brazil is now amongst India’s top 10 export destinations, with exports totaling US$9.6 billion in 2022. This massive increase in India’s exports to Brazil, 54 percent more than the previous year, owes mainly to the 295-percent increase in refined petroleum sales. India’s imports from Brazil increased by 38 percent from the previous year, buoyed by the 229-percent increase in soybean oil purchases.[8]

- The war in Ukraine has changed the edible oil equation: An immediate consequence of the war in Ukraine is the re-ordering of India’s edible oil imports. For decades, Ukraine has been the largest supplier of sunflower oil to India. Shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, India’s imports of sunflower oil from Ukraine dropped by 71 percent from the previous year.[9] India had to make up for this shortfall in edible oil imports, and Latin American countries like Argentina and Brazil stepped in. India’s imports of edible oil from Latin America increased from US$2.4 billion in 2020 to US$5.6 billion in 2022.

- An uptick in commodity prices and demand: The increase in commodity prices and inflation hurt many consumers globally but brought gains to suppliers of commodities. As one of the major global exporters of minerals and petroleum, Latin America ramped up its exports to India in 2022. The region’s mineral exports—specifically gold and copper ore—increased from US$4 billion in 2020 to US$8.6 billion in 2022.

For long, the lack of robustness in India-Latin America relations has been attributed by analysts, businesses, and the media, primarily to the issue of distance: Latin America is simply too far from India. Yet, while this may be true in geographical distance, advances in maritime trade and aviation have eased the movement of goods across the world.

The real challenge is not the physical distance that separates India and Latin America, but rather the distance in their perceptions. India and Latin America often still view each other from antiquated lenses: many Indians still remember Latin American countries as erstwhile ‘banana republics’, unstable economies with hyperinflation and burrows for drug trafficking; meanwhile, Latin Americans would still often think of India as the land of spiritualism and gurus. Indians need to discover the Latin America of today—a land of innovation in education, urban spaces and governance, as the world’s breadbasket and supplier of critical minerals, and a key emerging market. Latin America must also see India through a contemporary lens, as a global growth pole, a leader in technology and healthcare, and a breeding ground for startups.

This brief dissects how India and Latin America view one another, from the economic, political, and social lenses.

India’s Perceptions of Latin America

Economic

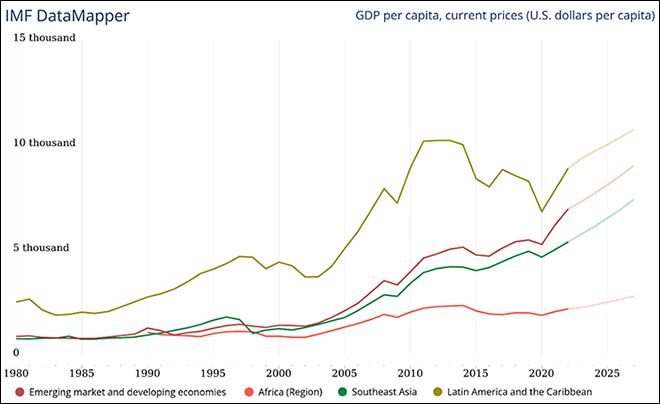

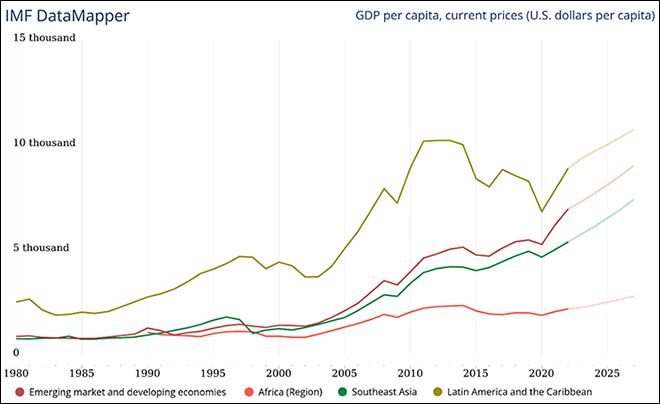

For Indian business, Latin America lies in the so-called ‘goldilocks zone’—a sweet spot between the highly regulated, competitive markets of the US and Europe, and the less competitive markets of Africa that have lower purchasing power. Indeed, as far as Indian business is concerned, Latin America is more comparable to Southeast Asia, but with higher purchasing power. In terms of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, Latin America currently stands at US$9,350, higher than Southeast Asia at US$5,750 and also the International Monetary Fund’s emerging market and developing economies classification at US$7,300; Latin America’s GDP per capita is also more than four times that of Africa’s at US$2,260 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Per Capita GDP, Select Regions

Source: The International Monetary Fund[10]

This is the primary lens with which Indian business views Latin America—as a bright spot and a growing market that is ripe for capture. No Indian company can be truly global without a reasonable presence in Latin America. Moreover, the region is a sought-after market for specific sectors that India thrives in, such as automobiles and vehicles, pharmaceuticals, information technology and services, and energy. It is thus no surprise that India exports more to Brazil than it does to Australia or Indonesia, for instance (see Table 1).

Table 1: India’s Exports, Select Countries (April 2022 to January 2023)

| Rank in India’s export basket |

Country |

Value in US$ Million |

| 9 |

Brazil |

8,504.75 |

| 10 |

Germany |

8,397.79 |

| 11 |

Indonesia |

8,278.34 |

| 15 |

South Africa |

7,279.50 |

| 16 |

Italy |

7,150.00 |

| 19 |

France |

6,501.17 |

| 21 |

Australia |

6,026.64 |

| 22 |

South Korea |

5,626.15 |

| 29 |

Mexico |

4,256.61 |

| 30 |

Spain |

3,792.70 |

| 32 |

Canada |

3,488.78 |

| 36 |

Russia |

2,482.57 |

| 48 |

Colombia |

1,243.45 |

| 49 |

Switzerland |

1,154.21 |

| 50 |

Austria |

1,068.51 |

| 51 |

Chile |

982.84 |

| 58 |

Portugal |

820.74 |

| 60 |

Argentina |

815.63 |

| 61 |

Sweden |

805.75 |

| 62 |

Morocco |

775.51 |

Source: Ministry of Commerce, Government of India

The Indian private sector’s footprint in Latin America is visible through its annual trade of nearly US$50 billion, as well as its total investments valued at US$16 billion—nearly all of which have been made in the past two decades.[11] These investments may not be as high as those from China, the US or Europe, but they are noteworthy because they create thousands of jobs in the region—more importantly, in value-added sectors, primarily in manufacturing and services. In certain sectors like pharmaceuticals, IT and vehicles, India often outcompetes China, which remains the largest trader for most South American countries. Throughout the 21st century, India exported more pharmaceutical products to Latin America than China did, although this changed in 2021 due to China’s export of Covid-19 vaccines to Latin America. Perhaps most important is India’s technological footprint in Latin America: Indian IT companies employ more than 40,000 people in the region, nearly all of whom are locals.

As a result, business and economics drives India-Latin America relations. India’s private sector continues to view Latin America in a favourable manner, prioritising the region as one of its main growth markets.

Political

Policymakers in New Delhi have given little attention to Latin America as the country has no deep political or strategic interest in the region. Latin America rarely inserts itself in the arena of geopolitics, no country in the region has nuclear weapons, and the region has not seen an intra-country war since the late 1800s. Consequently, Latin America has historically been consigned to the corners of India’s foreign policy priorities, to the last of the three concentric circles of India’s foreign policy.[b] In recent years, however, New Delhi’s political interests in Latin America have changed in two ways:

- Functional changes: India’s Ministry of External Affairs has kept the Latin American region at an arm’s length. The region falls under the purview of India’s minister of state for external affairs, a junior minister who works alongside the foreign minister. This changed in 2022, when three member countries of the G20 group—Argentina, Brazil and Mexico—were placed directly under the purview of India’s foreign minister. Since then, the Indian foreign minister has visited all three countries and engaged more deeply with each country in the numerous G20 forums that India is presiding over during its presidency in 2023.

- High-level dialogues: EAM Jaishankar has visited eight Latin American countries so far—a number that is unprecedented and gives momentum to India-Latin America ties. A number of Latin American leaders too, visited India in 2022 and plan to do so in 2023. These visits are usually accompanied by meetings between representatives from business and civil society on both sides. This renewed political interest can be leveraged to create new linkages and cement bilateral ties in the long-run by creating mechanisms for continued interaction between India and Latin America.

While these positive changes are welcome, two challenges remain. First, New Delhi has yet to formulate a mechanism to deal with the Latin American region as a whole—or even to engage meaningfully with the sub-groups in the region, such as the Central American Integration System (SICA in Spanish), the Pacific Alliance, and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC). This will continue to be difficult until Latin America achieves its long-running quest for regional integration. Until then, India must concentrate on its bilateral relationships with individual countries in the region. Moreover, it should deepen its relationship with SICA, CELAC, Mercosur,[c] the Pacific Alliance, as well as the Andean Community through regular dialogues.

Second, New Delhi has yet to exert political will to strengthen its economic relationship with the region primarily through the signing of free trade agreements (FTAs). The current preferential trade agreements (PTAs) that India has with Mercosur and Chile remain limited in scope; they are not nearly as comprehensive as India’s FTAs with South Korea, Japan or Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). This is despite India’s trade with Mercosur already having surpassed that with Japan.[12] While Latin American countries are keen to upgrade their PTAs with India to a full-fledged FTA, New Delhi has yet to signal its interest.

Social

The distance between India and Latin America is perhaps most acutely felt in the social interactions between both sides, which have been few and far between. Some historical exchanges between India and Latin America in the 19th and 20th centuries are noteworthy: these include people-to-people exchanges between India and Mexico, such as Pandurang Khankhoje, an Indian agricultural scientist who played a key role in the advancement of agricultural practices in Mexico; and MN Roy, an Indian political activist who founded both the Indian and Mexican Communist parties. There was also a constant exchange of goods, people and ideas between the Portuguese colonies and enclaves in India and Brazil. India and Latin America also saw a rich exchange of literary ideas through poet-diplomats and authors like Octavio Paz, Rabindranath Tagore and Victoria Ocampo, whose work helped influence mutual perceptions.

The 21st century has seen renewed social exchanges. One example is India’s poet-diplomat Abhay K, who has authored books of poetry on the Latin American region, such as The Alphabets of Latin America and The Prophecy of Brasilia. Abhay K notes: “From Tagore and Victoria Ocampo, to Cecilia Meireles and Octavio Paz, poets and writers have played a crucial role in building literary bridges between India and Latin America. This tradition has picked up pace in recent years with greater literary exchanges and has significantly contributed in promoting deeper understanding of India in Latin America and Latin America in India.”[13]

These social exchanges have increased gradually in the 21st century and there remains much scope to learn more from each other. After all, India and Latin America share certain similarly daunting challenges across various sectors, including financial inclusion, gender equality, poverty alleviation, and ending systemic corruption. India can and should learn more about Latin American concepts like ‘buen vivir’—literally ‘good living’ and a concept derived from indigenous communities in Latin America that emphasises a more environmentally sustainable society; India’s central and state governments can also learn from Latin America’s experience with conditional cash transfers (CCTs), given that the region is a pioneer in CCTs globally and has more than three decades of experience implementing such programs; finally, India can learn from the region’s programs of biodiversity conservation and the use of renewable energies.

The increase in people-to-people exchanges between India and Latin America is also visible through the presence of more than 90 Latin American football players in India’s local football tournament, the Indian Super League, as well as the proliferation of Latin American models and actors in India’s large and growing entertainment industry.

To be sure, distance can often be a challenge for increased social interactions between India and Latin America, perhaps most palpable in the high costs of travel. Oftentimes, Indians also find it difficult to obtain business or tourist visas to travel to Latin America. Yet, India enjoys tremendous goodwill in Latin America and this could make the difference in the long-run.

Latin America’s Perceptions of India

Economic

From an economic point of view, India has seen a resurgence in the 21st century. India’s economic growth is part of the overall story of the Global South, of which Latin America forms an integral part. Today, India is a massive market that no country can afford to ignore. It is also a means of economic diversification, vastly different from the economies in the Americas, Europe and Africa. For Latin America, India forms part of a larger, overarching Asia strategy. Soraya Caro, adviser at Colombia’s Superior Council of Foreign Trade, noted in an interview with this author that the government in Colombia has begun prioritising Asia and India for the first time, as a strategic and economic counterbalance to the country’s traditional partners in the West.[14]

India’s economic importance to the Latin American region has been most apparent in the past two decades. Since 2012, India has been amongst Latin America’s 10 largest export markets globally; in 2014, India was the third largest export destination for Latin America, after only the US and China. The region counts on India as a key partner for economic growth, as an importer of the region’s minerals, energy and agriculture, as well as an investor and job creator in Latin America. Today, India is the region’s largest export destination for vegetable oils, the third largest for copper ore, petroleum and gold, and the fourth largest for sugar and wood.

While a large majority of Latin America’s exports to India remain commodities, this trend has undergone a gradual change over the last decade as the region begins to export more value-added, finished products to India; these range from electronics produced in Mexico to processed foods from Brazil, wine from Argentina and fresh fruits from Chile. India has also become a significant investment destination for Latin American companies, particularly Multilatinas (Latin American multinationals) that seek to enter India’s large consumer market. Companies like Cinépolis from Mexico—presently the largest Latin American investor in India—have placed a long-term bet on India. More than three dozen Latin American companies have established their operations in India, investing nearly US$2 billion over the past two decades.[15] Javier Sotomayor, Managing Director for Cinépolis Asia, credits his company’s 15 successful years in India to economies of scale, demographics, and social stability.[16]

Both these trends—of Latin American exports of value-added products, and Latin American investments in India—are on the rise and will see more momentum in the coming decade in parallel to India’s economic growth and the expansion of its middle class.

Political

Given the sheer size and global profile of India, Latin American countries have always had a political interest in deepening their relationship with India. Latin American and Caribbean heads of government have visited India more than 30 times since India’s independence—this is far more than the reciprocal visits from India, when only four prime ministers have visited the Latin American region, and often to attend multilateral forums rather than conduct bilateral state visits.[17]

Still, Latin American politicians and governments have become more inclined to enhance their countries’ relationship with India. Brazil remains, by a large margin, the Latin American country with the most political linkages with India. This owes in part to Brazil’s membership in multilateral groupings like the BRICS, IBSA (India, Brazil and South Africa), as well as the G20. The other two Latin American members of the G20—Argentina and Mexico—have also given more attention to India over the past year due to India’s presidency of the grouping. The foreign ministers from Argentina, Brazil and Mexico have visited New Delhi as recently as in early 2023 and remain in constant dialogue with their counterparts in India. Peru’s Ambassador to India Javier Paulinich, who is on his second posting to the country, notes that India and Latin America benefit as much from economic complementarity and diversification as they do from shared values such as democracy and social development.

The political will from Latin America was also apparent in the signing of the PTAs between India and Chile, and India and Mercosur. Both Chile and Mercosur were intent on signing more broad-ranging FTAs with India, but settled for a PTA that could later be upgraded. While the India-Chile and India-Mercosur PTAs have been upgraded, they are still less robust than an FTA; the South American capitals in Mercosur and Chile will continue to lobby for a more meaningful FTA with India.

More recently, India and Latin America have also crossed paths in a rather new form of non-alignment—something that New Delhi calls ‘strategic autonomy,’ and Latin Americans call ‘Active Non-alignment’ (ANA). In their book, ‘Latin American Foreign Policies in the New World Order: The Active Non-Alignment Option,’ Chilean authors Jorge Heine, Carlos Fortin and Carlos Ominami note that ANA is “not about transferring in a monotonic fashion, an approach that originated in the 1960s and 1970s to the very different realities of the new century. On the contrary, the challenge lies in adapting concepts and terms rooted in another era to those of a world in rapid change and doing so with the necessary amendments and adjustments.”[18]

Over the course of 2022 and 2023, India and Latin America have maintained similar positions of ANA with regards to the war in Ukraine. They choose to focus on protecting their own national interests and reducing the overarching economic fallout of the war on inflation and interest rates.

Social

The Latin American region’s social perception of India began to be shaped by numerous literary and political figures over the 20th century. Perhaps most important is Octavio Paz, the Mexican poet-diplomat whose book Vislumbres de la India (In Light of India) remains one of the first points of knowledge about India for Latin Americans. Paz, who posted as ambassador to India from 1962 to 1968, writes: “Everything that I saw (in India) was the re-emergence of forgotten pictures of Mexico.”[19]

Many Latin Americans are also well-versed with Rabindranath Tagore, who spent two months in Argentina in 1924. Tagore’s literary works are available in Spanish and were distributed across the region through the translations by Mexican philosopher José Vasconcelos. Tagore’s relationship with Victoria Ocampo continues to be a subject of interest even today, as witnessed in the recent film ‘Thinking of Him’ by Argentine director Pablo Cesar. Another well-known Indian figure in Latin America is Mahatma Gandhi, whose teachings of non-violence remain relevant today and are celebrated by organisations like Palas Athenas in Brazil. In the 1960s, Latin Americans were introduced to a political figure from India—Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who visited eight Latin American and Caribbean countries in 1968, at a time when female heads of government were a rarity.

India’s image has seen a gradual change in Latin America in the 21st century, but most people in the region are still not acquainted with the contemporary reality of India. Caminho das Índias, a Brazilian telenovela that aired in 2009, gave Brazilians a birds-eye view of the clash between historical and modern India; it became so popular globally that the telenovela even won an Emmy Award in 2009. Although Latin Americans are discovering more about India in the 21st century, there is still some way to go until India enters the ‘mind map’ of the people in the region. “India’s presence in Latin America cannot be compared with other Asian or European countries, let alone the United States. There remains far more to be done before India can grab the attention of the general populace in Latin America,” notes ‘Leveraging India’s Goodwill in Latin America as ‘Soft Power’, an article in the Rupkatha Journal.[20]

Conclusion

As recently as the end of the 20th century, India was a distant, insignificant market for Latin America, and the Latin American region remained far outside India’s priorities, whether economic or political. This has changed rather suddenly and dramatically in the 21st century. Today, India is amongst Latin America’s most important trade partners, and the reverse is true, too—if the region were a country, it would be the fifth largest trade partner for India.

While business and economics has primarily driven India-Latin America ties, the supportive role of government could catalyse deeper and more expansive India-Latin America relations, and also redraw perceptions to reflect a more contemporary reality. Latin America will continue to have a role in India’s ambition to become a global power, and also part of the ‘goldilocks zone’ for Indian business. An increasing number of Indian companies are acknowledging that they cannot be truly ‘global’ without establishing a reasonable presence in Latin America.

Ambassador R. Viswanathan, a former Indian diplomat and an expert on Latin America and consultant to Indian companies, noted in a recent interview with this author that Latin America sees India as a hedge against the region’s overdependence on either China or the West. He adds that Indians and Latin Americans share emotional and cultural similarities, and also face similar developmental challenges.[21]

It would be in New Delhi’s interest to keep a sharp eye on Latin America and pursue two specific issues. First, to upgrade the current PTAs with Chile and Mercosur to FTAs, and also sign new, comprehensive trade agreements with other countries in the region like Peru, Colombia and Mexico. Second, New Delhi should seriously court Latin America as a provider of lithium and copper, both of which are indispensable commodities required to transition to green energy. While some challenges still remain in India-Latin America ties, such as the lack of financing and direct trade routes, the primary issue remains the misperception and the lack of knowledge between India and Latin America. The recent political overtures and the visits by high-level officials between India and Latin America are positive signs. Still, far more needs to be done to achieve the full potential of India-Latin America ties, but the 21st century has seen a promising start.

Hari Seshasayee is a Visiting Fellow at ORF. He serves as an Asia-Latin America Expert (United Nations Development Programme) and Adviser, Senior Dispatch, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Panama.

Endnotes

[a] This author is Adviser, Senior Dispatch, Ministry of Foreign, Affairs, Government of Panama.

[b] The first circle consists of India’s neighbourhood. The second includes Asia (SE Asia, West Asia, East Asia and Central Asia) as well as strategic partners. The last circle has countries in Africa and Latin America, the Pacific Islands, and others with which it has relations.

[c] Mercosur is a customs union and grouping consisting of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay.

[1] S Jaishankar, “Addressed the valedictory session of the international conference: Connected Histories, Shared Present at India International Centre,” Facebook Watch.

[2] Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Government of India.

[3] “Trade Map,” International Trade Centre.

[4] Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Government of India.

[5] Data based on calculations from Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Government of India, for Financial Year 2023 (as per the latest data available, for April 2022 to January 2023)

[6] Data based on calculations from Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Government of India, for Financial Year 2023 (as per the latest data available, for April 2022 to January 2023)

[7] Data based on calculations from Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Government of India, for Financial Year 2023 (as per the latest data available, for April 2022 to January 2023).

[8] Data based on calculations from Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Government of India, for Calendar Year 2022.

[9] Data based on calculations from Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Government of India, for Financial Year 2023 (as per the latest data available, for April 2022 to January 2023).

[10] IMF DataMapper, “GDP per capita, current prices,” International Monetary Fund.

[11] Hari Seshasayee, “Latin America’s Tryst with the Other Asian Giant, India,” Woodrow Wilson Center, May 2022.

[12] Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Government of India.

[13] Personal interview

[14] Personal interview

[15] Hari Seshasayee, “Latin American Investments in India: Successes and Failures,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 321, June 2021, Observer Research Foundation

[16] Personal interview

[17] Calculations based on annual reports from Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India and the websites of Indian Embassies in the Latin American and Caribbean region.

[18] Fortin, Carlos, Jorge Heine, and Carlos Ominami, eds. Latin American Foreign Policies in the New World Order: The Active Non-Alignment Option. Anthem Press, 2023.

[19] Embassy of Mexico in India, “Remembering Octavio Paz, 20 years after,” Medium, April 20, 2018.

[20] Seshasayee, Hari. "Leveraging India’s Goodwill in Latin America as ‘Soft Power’." Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities 14, no. 3 (2022).

[21] Personal interview

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV