-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Mitu Sengupta and Asit Arora, “Protecting Cancer Care through the Covid-19 Crisis and its Aftermath,” ORF Issue Brief No. 391, August 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has demanded worldwide commitment of policy attention and resources on an unprecedented scale. A mounting concern is that care for COVID-19 patients will displace care for those with other illnesses such as cancer, especially in developing countries like India where health resources are already overstretched.

Cancer kills approximately 9.6 million people every year globally.[1] In India, cancer causes approximately 2,000 deaths every day.[2] India’s high death rate from cancer[3] is attributable to multiple policy failures such as limited access to timely diagnosis and effective treatment,[4] and is especially worrying given that the country’s cancer burden is projected to double in the next 20 years.[5]

In countries that were hit hard by the pandemic early on, cancer care suffered serious disruptions, including delays in diagnosis and treatment, and the halting of clinical trials. Alarming reports appeared in both the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US), for example, of even high-risk patients being left with changes, delays, or interruptions to their care.[6] In the US, a model created by the National Cancer Institute predicted that tens of thousands of excess cancer deaths would arise over the next decade because of missed screenings and other cutbacks in oncology care precipitated by the COVID-19 crisis.[7]

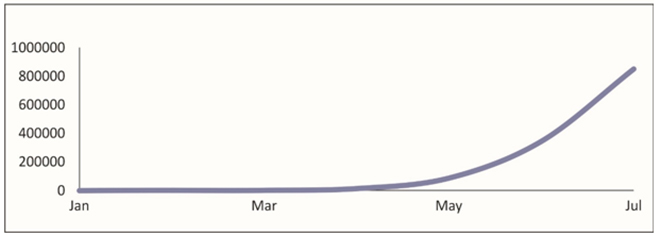

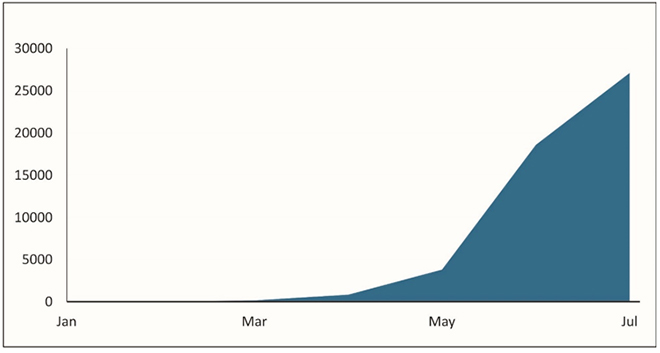

The initial months of the pandemic were relatively stable in India.[8] While various reductions in cancer care were reported,[9] specialist oncology services remained largely intact through the months of March, April, and May. The month of June, however, marked a clear turn for the worse. As the number of COVID-19 cases increased briskly, so did the strain on the country’s health systems. Notably, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases jumped from 198,370 on 1 June 2020 to 604,641 on 1 July 2020[10] (See Figures 1 and 2)

Figure 1. Confirmed COVID-19 Cases in India (Jan-Jul 2020)

Figure 2. Daily COVID-19 Cases in India (Jan-Jul 2020)

Over the next few months, India’s healthcare system is likely to remain under intense pressure. In this scenario, one can expect cancer patients to be thrust into competition with Covid patients for hospital ward and ICU beds, ventilators, blood products, staff, and even basic medical supplies. This threatens the well-being of individual cancer patients and the many important advancements made in oncology care. This is because, despite cancer’s heavy mortality burden in India, the disease did not receive appropriate policy salience until fairly recently.[11] In the last five years, new treatment centres were built in different parts of the country, awareness campaigns were launched, and clinical trials materialised. Moreover, in 2018, the Ayushman Bharat Health and Wellness Centres Program was initiated—a landmark intervention that aims to integrate screening for cancer and other non-communicable diseases into India’s primary healthcare system.[12]

India can learn from the experience of countries that were battered by the virus in the initial phases of the pandemic. The country can avoid the surprise assault on cancer care that nations such as Italy and Spain had to endure. A substantial body of literature has emerged on managing cancer care during the COVID-19 crisis that is built on the observations of oncologists practicing in the worst-off countries, as well as guidelines issued by professional societies such as the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the UK’s National Health Service (NHS).[13]

This brief draws upon the literature, as well the authors’ own clinical and practical experience, to specify some important challenges that will need to be met in three priority areas, by both healthcare providers and public policymakers, if cancer patients and their care are to be safeguarded through the course of the coronavirus pandemic and the recovery period thereafter. These challenges are in the areas of service delivery, access to care, and communication.

Priority Areas for Cancer Care

Cancer patients tend to be older, have multiple comorbidities, and are immunosuppressed either by their disease or by anti-cancer therapy. Although the data is still limited, they appear to be at greater risk of severe complications and death from the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.[14]

While ideally, cancer patients should avoid all exposure to the virus while there is no vaccine or reliable therapeutic agent in sight, the reality is that many cancer treatments are highly time-sensitive and must be delivered swiftly, in clinical settings, to check the spread of cancer. If cancer is to be curable, moreover, it must be detected early, which means being vigilant about initial signs, and seeking immediate care should they arise. Since a corona-free world is unlikely any time soon,[15] most cancer patients will have no choice but to brave the outside world in order to obtain life-saving diagnosis and treatment. The onus will be on healthcare providers and government policymakers to protect them from the virus.

Cancer patients’ exposure to the virus can be minimised through a number of different methods, including (a) Segregation of cancer and Covid facilities; (b) infection control; and (c) treatment modification.

(a) Segregation of cancer care from COVID-19 care

Perhaps the most crucial step towards ensuring that cancer patients stay safe while obtaining care during the pandemic is to partition the facilities used to treat cancer patients from those for COVID-19 patients. Wherever possible, separate buildings or building blocks should be used. If cancer facilities are not fully segregated from Covid facilities, other efforts to minimise cancer patients’ exposure to the virus (such as infection control measures) are unlikely to be effective. The clear separation of cancer and Covid facilities is strongly recommended by the UK’s NHS and other international bodies and professional medical associations.

It is likely that as pressure on resources will not abate, government authorities will be prompted to order the insertion of COVID-19 patients into hospitals wherever there is room, without sufficient regard for other uses of these facilities. Multi-specialty hospitals, which are an important site of advanced cancer care in India, will be under special pressure in this scenario due to the country’s limited health infrastructure. Merging Covid patients into the same facilities as cancer patients, however, is not a defensible option given there is reasonably reliable data indicating that cancer patients are more at risk for serious complications from the virus than many other populations. If anything, government authorities have a special duty to protect cancer patients, who constitute a vulnerable group in the face of the pandemic.

(b) Infection control

In clinical settings, the objective of infection control is to reduce opportunities for viral transmission between patients, their caregivers, and medical staff. This may be achieved through a variety of means, such as replacing some patients’ clinic visits with virtual assessments via telemedicine; arranging for home delivery of oral medicines and home collection of blood samples; rigorous screening of patients and staff before permitting entry into outpatient clinics; controlling patient flow to minimise contact between patients; restricting the visits of relatives and other ‘attendants’ in outpatient clinics and inpatient wards; creating isolation wards for confirmed cases of COVID-19; transferring patients to other cities and regions that have less incidence of infections; establishing measures for aerosol containment during surgery, endoscopies, and emergency care; and instituting training courses for hospital staff on the proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE). Many of these protocols have already become standard Covid-preparedness practice in hospitals across India.

(c) Treatment modification

Another way to minimise a patient’s exposure to the virus is to modify aspects of their treatment with the intent of reducing the intensity or frequency of their hospital visits. Treatment modification may, in fact, become unavoidable if Covid patients end up overwhelming the system, and the burden on healthcare resources becomes acute. In Italy, for instance, which suffered the worst early outbreaks of the virus, treatment modification became a fairly routine response to the pandemic by oncologists.[16]

The decision to delay or otherwise modify cancer treatment is always a serious matter, involving evidence-based choices, made in accordance with the expectations of the patient and the clinical judgment of their treating oncologist, on a case-by-case basis, following a transparent logic. Several general considerations, in line with international guidelines, could be used to steer decisions on personalised treatment modification. These include the clinical condition of the patient, the biological features of the tumour, and the weighing of expected benefits of the treatment against expected adverse effects.

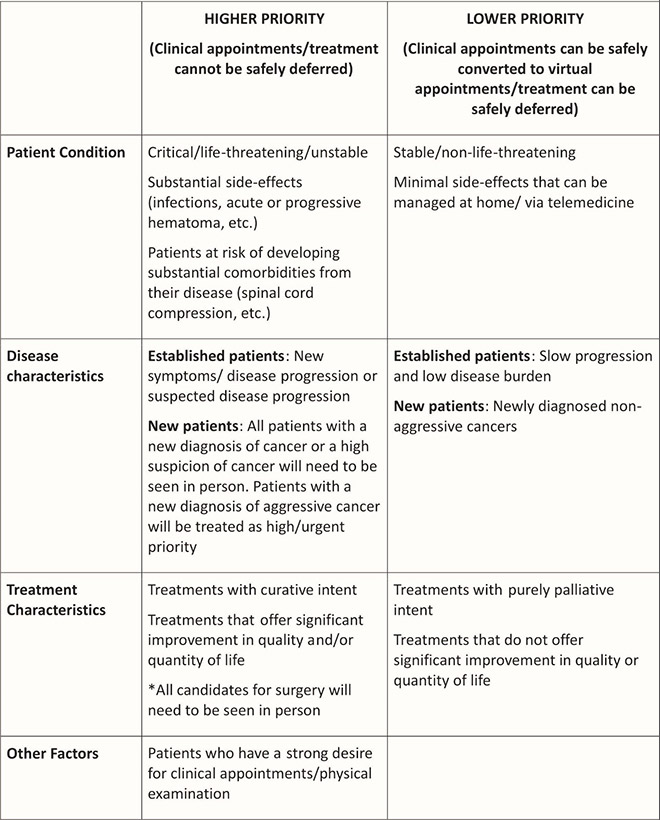

Accordingly, patients could be stratified into different priority groups for receiving active cancer therapy, with higher priority given to those whose condition is immediately life-threatening or clinically unstable; or who are at risk of developing serious comorbidities, such as spinal cord compression; or who have certain types of cancers, such as acute leukemia, that require immediate treatment. Lower priority could be given, on the other hand, to patients with early-stage breast or prostate cancers that do not require urgent treatment, or patients in second-line or third-line chemotherapy, where there is not much survival benefit associated with further treatment. While treatment modification would typically be avoided for higher priority patients, it could be considered for lower priority groups through different means, such as switching from intravenous therapies to oral therapies, or reducing the frequency of maintenance treatments. Complex surgeries that are likely to require multiple blood transfusions, respirator utilisation, and prolonged postoperative ICU care could also be postponed for lower priority groups. (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: An example of criteria that could be used to set cancer treatment modification priorities during the COVID-19 pandemic

Access to Care

Another important step towards safeguarding cancer care through the pandemic is to ensure that cancer patients retain physical and financial access to specialist services, which are crucial to treatment, as well as to primary health services, which are the first port-of-call for effective diagnosis.

(a) Financial access

In India, expenditure on cancer inpatient treatment is highest amongst all non-communicable diseases (NCDs), with out-of-pocket expenditure on cancer hospitalisation at about 2.5 times that of overall average hospitalisation expenditure. Many families resort to distressed modes of financing treatment, such as selling off household assets and borrowing from money lenders at extortionate interest rates.[17] Indeed, data show that poorer people with cancer are more likely to die of their disease before the age of 70 than those who are more affluent.[18]

The COVID-19 pandemic will only likely worsen a bad situation. The income and job losses that are following it across the world are playing out in India as well, and will leave many cancer patients and their loved ones with even less resources to pay for treatment. Given that most cancer patients are already under heavy financial stress, they should be targeted for different forms of financial support from the government as well as private sources – in the form of grants, special loans, insurance schemes, etc. –

throughout the course of the pandemic as well as during the recovery phase. Without such support, there will be more people dropping out of treatment and facing premature death in the future.

(b) Physical access

The poor geographical spread of medical services in India means that cancer patients will often need to travel long distances to access reliable care.[19] The availability of safe, reliable modes of transport is especially urgent, given that the burden of cancer is significantly higher among the elderly (70+) cohort in India, at about 385 per 100,000 persons (as compared with the overall cancer prevalence of 83 per 100,000 persons).[20]

The ‘lockdown’ phase of the Covid crisis in India was marked by complex restrictions on intra- and inter-state travel and massive disruptions in public transport systems. For many cancer patients and their families, this posed grave difficulties. Arivazhagan, a 65-year-old farm labourer in Tamil Nadu, had to travel 130 km on his bicycle from his village to a cancer centre in Puducherry, so that his wife could receive her planned chemotherapy dose on time. He was stopped by the police multiple times, and was only able to move forward after producing his wife’s medical records and chemotherapy schedule.[21] Arivazhagan’s case is presumably the exception rather than rule as the typical caregiver would be put off by the prospect of such an arduous and risky expedition with their patient. It is reasonable to assume that the Covid crisis has discouraged tens of thousands of people from obtaining medical attention, which is why fewer people are accessing treatment at all levels of the system.[22]

At the time of writing, many Covid-containment measures relating to movement and travel have only been partially lifted. Given the recent rapid spikes in Covid cases in many parts of the country, it is possible that state border closures and other limitations on travel, including passage within the city or region, will linger on for months. This will pose enormous difficulties for cancer and other non-Covid patients who are in need of time-sensitive care. Such patients should be provided with effective, targeted support – for example, in the form of simplified procedures for obtaining travel passes – as they navigate their way through Covid-related bottlenecks in the country’s transport systems.

(c) Access to primary health

The grim reality in India is that the majority of cancer cases are diagnosed in advanced stages, when treatment outcomes are poor, and many cancer cases are associated with preventable causes such as infections and tobacco use. For a vast majority of the country’s population, it is the primary healthcare provider who is first approached with complaints of symptoms that could be indicative of cancer, and who holds the key to the timely screening and referrals that are essential for the early detection of cancer. Since the primary healthcare provider is also responsible for promoting cancer awareness, any malfunction at this level could lead to a significant jump in cancer deaths in the future.

While studies on the subject are still preliminary, it seems that India’s primary healthcare system has been hit by a massive diversion of material and human resources to manage the pandemic.[23] It is being reported, for example, that much of the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) workforce has been diverted to service Covid-related health concerns, and that ASHAs who have not been diverted have had their door-to-door movement restricted.[24] Since ASHAs are typically the first healthcare resource to be accessed by poor and marginalised segments of the population, especially women and children in rural areas, any rupture in their services is likely to generate negative consequences.

The routine work performed by ASHAs in community healthcare – such as the promotion of maternal health, child immunisation, and family planning – appears to have already suffered, with reports emerging of curtailed child immunisation schedules, reduced maternal health services, and lowered access to mental health treatment.[25] The disruption of ASHAs should also be a source of concern for those who are interested in cancer care, since at least some ASHAs have been trained in cancer prevention, particularly in the screening and diagnosis of cervical cancer and breast cancer.[26] In India, where early detection constitutes a major health-system gap and is the leading factor behind the country’s high cancer death rate, ASHAs help address a vastly unmet need. For all of these reasons, restoring the services of ASHAs and other primary healthcare workers to non-pandemic tasks should be treated as a priority policy issue.

The most crucial step towards safeguarding early detection initiatives at the primary level, however, will be to ensure that the Health and Wellness Centres piece of the Ayushman Bharat Program (AB-HWC) is protected and rolled out according to plan (the target is to have 150,000 HWCs operational by December 2022).[27] The AB-HWC is a groundbreaking intervention because it aims to systematically strengthen the previously anaemic promotive and preventive dimension of India’s primary healthcare system. Key additions to primary health envisioned under AB-HWC that are relevant to cancer care include cancer screening and other diagnostic services, mental health services, palliative care services, and healthy lifestyle counselling. If implemented properly, the AB-HWC initiative will revolutionise primary health in India and help close the gap in early detection services that is responsible for many unnecessary cancer deaths.

Communication

In the words of the U.N. Secretary General, the COVID-19 pandemic has been accompanied by a parallel ‘infodemic’ of fake news.[28] False and misleading information about the pandemic has been plentiful in India, and like elsewhere, has created confusion, anxiety, and distrust among people and communities, and has served to stigmatise doctors, nurses, and other frontline medical personnel.[29]

False information about the pandemic has also deterred people from seeking time-sensitive medical diagnosis and treatment. Many cancer patients have been led to believe that there are no reliable ways of avoiding infection from the virus while accessing medical care. This, of course, is untrue. If proper infection control measures are in place, cancer treatment can be delivered safely – and is beingdelivered safely – in hospitals and other clinical settings. While, admittedly, nothing will be 100-percent safe while the virus is still active, for most cancer patients, the survival benefits of receiving timely treatment greatly outweigh the risks of infection with Covid.[30]

A key challenge for healthcare providers and public policymakers is to ensure that cancer patients are provided clear and trustworthy information about how to manage their illness within the parameters of the pandemic. False and misleading statements about the pandemic must be countered aggressively, and reliable, evidence-based knowledge must be communicated effectively. Better regulation of social media platforms is one of many initiatives that could be considered for achieving such goals.

For their part, cancer patients and their caregivers should be on alert for false and misleading information about the virus, particularly about its mode of transmission, symptoms, origins, and so-called miracle cures. Information about the pandemic should be obtained only from reliable, official sources, such as the World Health Organization’s Covid-19 Response portal and India’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare’s Coronavirus portal.[31]

Most crucially, cancer patients should never take decisions to delay or modify any aspect of their treatment without first consulting with their treating oncologist.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic is an emerging, rapidly evolving public health emergency of international concern that has taken an enormous toll on economies, societies, and health systems across the world. According to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre, which is updated daily, there were approximately 17.8 million confirmed cases and 679,516 deaths worldwide, and 1.75 million cases and 37,364 deaths in India, at the time of producing this brief.[32]

Given that cancer is a major illness in India, with a dire death toll of more than 2,000 persons per day, it should be a matter of urgent concern that cancer care could be severely undermined by efforts to manage the pandemic. It should be noted that this is what has happened in developed countries such as the UK and US, which, despite having stronger health systems than India’s, are estimating excess cancer deaths in the range of tens of thousands.[33] If cancer care suffers similar damage in India, the country’s already-high cancer mortality rate will increase even further. Oncology care, which is still at a developmental stage in the country, will also suffer a major setback.

It is still possible, however, to avert this scenario by taking a number of carefully planned steps that draw on the experience of countries that have already gone through acute constraints in their healthcare resources as a result of COVID-19. These steps, in the areas of service delivery, access to care, and communication, have been described in detail in this brief, and are key to ensuring that cancer patients retain access to the highest possible standards of care during the Covid crisis as well as its aftermath.

In the long term, many structural problems that have been laid bare by the pandemic—including India’s poor geographical spread of healthcare workers, weak telehealth networks, and chronically low investment in healthcare (never more than 1.3 percent of GDP)—will also need to be addressed with renewed commitment.[34]

About the AuthorsMitu Sengupta is Full Professor, Department of Politics and Administration, Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada. She is also Visiting Professor at the Council for Social Development (CSD), and Senior Adjunct Fellow at Research and Information Systems for Developing Countries (RIS), New Delhi. Dr. Asit Arora is Principal Consultant, Gastrointestinal and HPB Oncosurgery, Max Institute of Cancer Care, Delhi. The views expressed by the authors are their own.

Endnotes

[1] “Cancer: Key Facts,” World Health Organization, accessed August 1st, 2020.

[2] “Cancer Statistics,” India Against Cancer, accessed August 1st, 2020. According to this website, the total number of deaths due to cancer in 2018 was 7,84,821.

[3] It is noteworthy that cancer’s mortality-to-incidence ratio in India, of about 0.68, is far higher than what it is in developed countries. See Seema Gulia et al., “National cancer control programme in India: proposal for organization of chemotherapy and systemic therapy services,” Journal of Global Oncology, 3, no. 3 (June 2017): 271-74.

[4] Many factors, including poor science literacy and misinformation, impede the early detection of cancer in India, which is the main culprit behind the country’s heavy mortality burden from the disease. See Bhawna Sirohi, “Cancer care delivery in India at the grassroot level: improve outcomes,” Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology,” 35, no. 3 (2014): 187-191, https://doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.142030.

[5] Mayank Singh et al., “Cancer research in India: challenges and opportunities,” Indian Journal of Medical Research, 148, no. 4 (2018): 362-365, https://doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1711_18. Growth in India’s cancer burden, as this article suggests, is attributable to a complex mix of factors including increased life expectancy.

[6] See Sarah Marsh and Sophie Cohen, “Coronavirus crisis is ‘stopping vital cancer care’ in England“, The Guardian, April 4, 2020, and Roxanne Nelson, “Cancer patients report delays in treatment because of Covid-19,” Medscape Medical News, April 17, 2020.

[7] Norman E. Sharpless, “Covid 19 and Cancer,” Science, 368, no. 6497 (2020): 1290, https:// doi: 10.1126/science. abd3377.

[8] There are no definitive answers as to why the virus ravaged some parts of the world early on while leaving others relatively unscathed. See Hannah Beech et al., “The Covid-19 riddle: why does the virus wallop some places and spare others?” The New York Times, May 3, 2020.

[9] Sanchita Sharma, “Cancer care takes a hit during lockdown”, Hindustan Times, June 21, 2020. Also see Bhavya Dore, “Covid-19: collateral damage of lockdown in India,” The BMJ, 369 (2020): m1711.

[10] These numbers are obtained from the Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Centre, which is updated daily. “Covid-19 Dashboard,” Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Centre, accessed August 1st, 2020.

[11] Developing countries like India have historically given greater priority to combating communicable (or infectious) diseases, such as tuberculosis and cholera, than to non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, stroke, and cancer. Even in 2014, public expenditure on cancer in India was below US$10 per person (compared with more than US$100 per person in developed countries). See C.S. Pramesh et al., “Delivery of affordable and equitable cancer care in India,” The Lancet Oncology, 15, no. 6 (May 01, 2014): 223-233.

[12] For a detailed discussion of the HWC program, see Chandrikant Lahariya, “Health & Wellness Centres to strengthen primary health care in India: concept, progress, and ways forward,” The Indian Journal of Pediatrics (published online ahead of print July 8, 2020): 1–14.

[13] Some examples of this literature are: Matteo Lambertini et al., “Cancer care during the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy: young oncologists’ perspective.” ESMO Open, 5, no. 2 (2020): pp. 1-4, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000759; Talha Khan Burki. “Cancer guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic,” The Lancet Oncology, 21, no. 5 (May 01, 2020): 629-630; and Timothy Hanna et al., “Cancer, COVID-19 and the precautionary principle: prioritizing treatment during a global pandemic,” Nature Reviews: Clinical Oncology, 17 (2020): 268-270.

[14] Wenhua Liang et al., “Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China,” The Lancet Oncology, 21, no. 3 (March 01, 2020): 335-337, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. This widely-cited report currently provides the largest series (n= 1,590) on how Covid-19 outcomes may vary between patients with and without cancer. It suggests that cancer is associated with an increased risk of death and/or intensive care unit admission. The strength of this finding is limited, however, by the small sample side (data from only 18 patients with cancer are included).

[15] See Stephen M. Kissler et al., “Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period,” Science, 368, no. 6493 (May 2020): 860-868. Kissler et al. suggest that the threat of virus resurgence could linger until 2024.

[16] See, in particular, Lambertini et al., “Cancer care during the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy: young oncologists’ perspective,” 1-4.

[17] See William Joe, “Distressed financing of household out-of-pocket health care payments in India: incidence and correlates,” Health Policy and Planning, 30, no. 6 (July 2015): 728-741.

[18] See Mohandas K. Mallath et al., “The growing burden of cancer in India: epidemiology and social context,” The Lancet Oncology, 15, no. 6 (May 01, 2014): 205-212.

[19] Anup Karan et al., “Size, composition and distribution of human resource for health in India: new estimates using National Sample Survey and Registry data,” BMJ Open, 9, no. 4 (2019). Karan et al. indicate that the health workforce density in rural India and states in eastern India is lower than the WHO minimum threshold of 22.8 per 10,000 population.

[20] Sunil Rajpal et al., “Economic burden of cancer in India: evidence from cross-sectional nationally representative household survey, 2014,” PLoS One, 13, no. 2 (2018): e0193320.

[21] Bosco Dominique, “Tamil Nadu man cycles 130km with wife to give her cancer care on time”, The Times of India, April 11, 2020.

[22] For a report of the scenario at the primary level, see S. Rukmini, “How covid-19 response disrupted health services in rural India,” Live Mint, April 27, 2020.

[23] S. Rukmini, “How covid-19 response disrupted health services in rural India.”

[24] See Neetu Chandra Sharma, “Primary healthcare to take a back seat in Covid battle.” Live Mint, April 16, 2020.

[25] See S. Rukmini, “How covid-19 response disrupted health services in rural India.”

[26] See Farjana Memom et al., “Can urban Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) be change agent for breast cancer awareness in urban area: experience from Ahmedabad, India,” Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8, no. 12 (December 2019): 3881-3886.

[27] This will include both new facilities as well as upgraded versions of existing facilities. See Lahariya, “Health & Wellness Centres to strengthen primary health care in India: concept, progress, and ways forward.”

[28] The term ‘infodemic’ was used by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Tedros Ghebreyesus to emphasize the scale of the misinformation that has accompanied the pandemic. “UN tackles ‘infodemic’ of misinformation and cybercrime in COVID-19 crisis,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), accessed August 1st, 2020.

[29] See Niranjan Sahoo, “How fake news is complicating India’s war against COVID-19,” Observer Research Foundation: India Matters, May 13, 2020.

[30] This point is clearly stated in Timothy Hanna et al., “Cancer, COVID-19 and the precautionary principle: prioritizing treatment during a global pandemic,” Nature Reviews: Clinical Oncology, 17 (2020): 268-270.

[31] “Coronavirus disease (Covid-19) advice for the public,” World Health Organization (WHO), accessed August 1st, 2020, and “Novel Corona Virus,” Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, accessed August 1st, 2020.

[32] “Covid-19 Dashboard,” Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Centre, accessed August 1st, 2020.

[33] See, for example, “Coronavirus could cause 35,000 extra UK cancer deaths, experts warn,” BBC News, July 6, 2020).

[34] On this see Madhavi Mishra and Nandita Bhan, “The Covid-19 emergency in India: an investment case for health like never before,” Observer Research Foundation: Expert Speak, May 10, 2020.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Mitu Sengupta is Full Professor Department of Politics and Administration Ryerson University Canada. She is also Visiting Professor at the Council for Social Development (CSD) ...

Read More +

Asit Arora is Principal Consultant Gastrointestinal and HPB Oncosurgery Max Institute of Cancer Care Delhi.

Read More +