-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Shoba Suri and Kriti Kapur, “POSHAN Abhiyaan: Fighting Malnutrition in the Time of a Pandemic,” ORF Special Report No. 124, December 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

Child and maternal undernutrition is the single largest health risk factor in India, responsible for 15 percent of India’s total disease burden.[1] Malnutrition in children manifests either in the form of ‘stunting’ (low height in relation to age) or ‘wasting’ (low weight in relation to height) or both. India is home to almost one-third of all the world’s stunted children (46.6 million out of 149 million) and half the world’s wasted children (25.5 million out of 51 million).[2] Data from the fourth National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) of 2015-16 shows that 38 percent and 21 percent of children under five years are, respectively, stunted and wasted.[3] At the same time, the rate of obesity in children under five, adult women and adult men has risen to 2.4 percent, 20.7 percent and 18.9 percent, respectively. India thus faces the double burden of malnutrition and obesity.

India also lags behind on other nutritional indicators, with high levels of anaemia in women of reproductive age and low prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding of infants during their first six months. Almost 50.4 percent of women in the 15-49 age group suffer from iron deficiency anaemia, and only 55 percent of children are exclusively breastfed for six months. The Global Nutrition Report 2020[4] notes that India is among the 88 countries that will miss their global nutrition targets of 2025. India has the highest rates of domestic inequalities in malnutrition, and the biggest disparities in children’s heights.

Poor nutrition in the first 1,000 days after birth leads to stunted growth, leading to an intergenerational cycle of malnutrition.[5] Malnutrition keeps people from reaching their full potential, affecting not only their health, but also their social and economic development.[6] The cost of malnutrition on the global economy is huge, at US$3.5 trillion per year or US$500 per individual.[7]

In 2017, India launched the POSHAN Abhiyaan—a flagship national nutrition mission to improve nutrition amongst children, pregnant women, and lactating mothers. This year, the COVID-19 pandemic has potentially reversed much of the progress made towards meeting the second of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): ending hunger, achieving food security, and improved nutrition. Eastern India, in particular, has been hit by twin disastrous events—the pandemic and Cyclone Amphan, which struck in May and left death and destruction in its wake. This has placed the region, and consequently its most vulnerable population, its children, at higher risk of malnutrition, food insecurity, and disease exposure.

Budget 2020-21[8] witnessed an enhanced allocation of INR 35,600 crore for nutrition-related programmes and an additional INR 28,600 crore for women-related programmes. Odisha[9] set an example by becoming the first state to prepare a separate budget document for nutritional interventions. However, the spread of COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdowns have thrown the economy and government finances into turmoil. The scale of the challenge in tackling child malnutrition is undeniable and calls for nutrition-specific budgets for the nation, states and cities.

In light of the pandemic, Observer Research Foundation (ORF), in collaboration with the Ministry of Women and Child Development, organised a digital discussion on ‘Food Insecurity, Malnutrition, Poverty, Cyclone amid COVID Crisis in Eastern India’. This discussion brought together diverse opinions from government, academic institutions, develpment partners, international organisations, and members of civil society. It aimed to understand the critical challenges faced by nutrition programmes in eastern India during the pandemic and the lockdowns that have led to the disruption of nutrition services. It sought to draw learnings from the experience of other states, seeking examples of successful scaling. This special report builds on the ideas shared during the discussion.

India’s Nutrition Challenge: An Overview

The Global Nutrition Report 2020[10] notes that malnutrition continues to be one of India’s biggest challenges. It suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic could well reverse the progress in reducing malnutrition and hunger achieved so far.

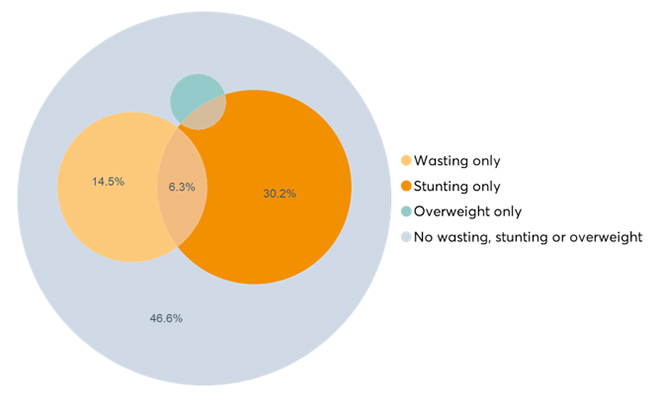

Figure 1 shows the co-existence of wasting, stunting and obesity amongst India’s under-five population. An analysis of national data[11] shows that there has been an increase in obesity in this section from 1.9 percent in 2006 to 2.4 percent in 2015-16. At the same time, stunting and wasting, at 38 percent and 25 percent, respectively, are much higher than the global developing country average[12] of 25 percent and 8.9 percent, respectively.

Figure 1: Percentage of children under five years with co-existence of wasting, stunting and obesity

In the Global Hunger Index 2020, India falls in the category of ‘serious hunger’, ranking 94th among 107 countries. India has progressed since the last such ranking, when it stood at 102 out of 117 countries. On the World Bank’s human capital index, India ranks at 116 out of 174 countries, showing steady progress in building human capital conditions for children. However, the pandemic[14] has put at risk the decade-long progress in improving human capital, including health, survival, and reduction of stunting, leading to food insecurity and poverty. At the same time, the lack of adequate investment in health and education has also led to slower economic growth. Stunting has lasting effects – a World Bank study[15] suggests that a one-percent shortening in adult height because of childhood stunting is associated with a 1.4-percent loss in economic productivity.

Despite substantial economic growth in India over the past decades, stunting in children under five reduced by only one-third between 1992 and 2016, and continues to remain high at 38.4 percent.[16] Barring Puducherry, Delhi, Kerala and Lakshadweep, all other states have a higher proportion of stunted children in rural areas than in urban. Data indicates that stunting increases with age in the early years, peaking at 18-23 months. It is irreversible after the first 1,000 days. Stunting[17] also leads to an intergenerational cycle of malnutrition.

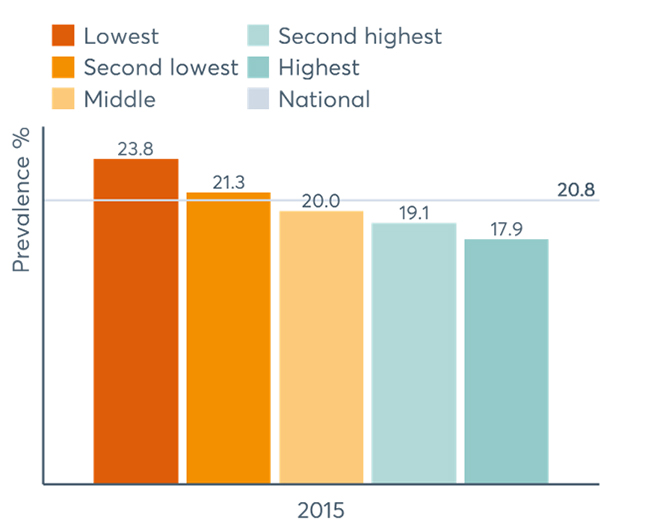

Figure 2: Percentage of wasting (by income) in children under 5 years of age

In 2015-16, more than one-third of children (35.7 percent) were reported underweight, which was, however, a reduction from 42.5 percent in 2005.

Malnutrition[20] in adults too cannot be ignored, with 23 percent of women and 20 percent of men in the 15-49 age group being underweight. Almost the same proportion – 21 percent of women and 19 percent of men – are overweight.

Timely interventions of breastfeeding, age-appropriate complementary feeding, full immunisation, and Vitamin A supplementation[21] have been deemed essential in enhancing nutrition outcomes in children. However, only 41.6 percent of children are breastfed within one hour of birth, only 54.9 percent are exclusively breastfed in their first six months, and just 42.7 percent are given timely complementary foods.[22] Furthermore, only 9.6 percent of children below two years receive an adequate diet. A more recent survey indicates a further decline to 6 percent in children receiving a minimum adequate diet.[23]

Anaemia is a public health problem affecting both children, and women in the reproductive age group. It not only leads to increased maternal mortality, but also delayed physical and mental development.[24] Poor nutrition is the underlying cause of anaemia. More than half the women of reproductive age (50.4 percent) are anaemic.[25] From 2005 to 2015, there has been a decline in the proportion of anaemic children and pregnant women by 11.1 and 8.5 percentage points, respectively. Anaemia prevalence in women shows wide variation across states, ranging from 9 percent to 83 percent.

India’s Nutrition Programmes

India is committed to addressing its nutritional challenges. In past decades, various programmes and schemes have been launched and expanded to improve the nutritional situation of the country. The oldest scheme, the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), launched in 1975, adopted a multi-pronged approach to children’s well-being by integrating health, educational and nutritional interventions through a community network of anganwadi centres (AWCs). The measures initiated included a supplementary nutrition programme, growth monitoring and promotion, nutrition and health education, immunisation, health checkups and health referrals, as well as preschool education. The primary beneficiaries were children below six years, as well as pregnant and lactating women. Today, the anganwadi services scheme operates through a network of 7,075 projects, implemented across 1.37 million anganwadi centres, providing supplementary nutrition to 83.6 million beneficiaries.[26] Between 2006 and 2016, owing to the programme, supplementary nutrition intake increased from 9.6 percent to 37.9 percent; health and nutrition education from 3.2 percent to 21 percent; and child specific services of immunisation and growth monitoring from 10.4 to 24.2 percent.[27]

The Midday Meal scheme,[28] providing hot meals to children attending government schools, dates back to 1925, having been started locally by the Madras Municipal Corporation. To enhance enrollment, retention and attendance in schools, and simultaneously improve nutritional levels among children, it was launched nationally from 1995. About 91.2 million children across 1.14 million schools benefit from the scheme. [29]

Subsequent schemes started to nurture women and children’s health, including the POSHAN Abhiyaan, all functioning under the ICDS umbrella.[30] They include the Anganwadi Service Scheme, the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY), and the Scheme for Adolescent Girls. The National Food Security Act, 2013,[31] provides for subsidised food grains under the targeted public distribution system. It covers almost one-third of the population. The PMMVY is a maternity benefit programme, launched nationally in 2016, that provides a conditional cash transfer to pregnant women for safe delivery, and good nutrition and feeding practices. Complementing the PMVVY, is the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY), wherein the beneficiaries are also eligible for a cash incentive after institutional delivery.

Despite an array of programmes providing for food security and improved maternal and child health and nutrition, the uptake of services has remained low. Only 51 percent of pregnant women attend a minimum of four antenatal clinics and only 30 percent consume iron folic acid (IFA) tablets. Uptake of supplementary nutrition varies from 14 to 75 percent among children, and is 51 percent and 47.5 percent among pregnant and lactating women respectively. Only 50 percent of pregnant and lactating women are enrolled in the maternity benefit scheme across states. Correct infant and young child feeding practices remain low. Timely initiation of breastfeeding is only at 42 percent, despite 79 percent deliveries being institutional. Exclusive breastfeeding for six months is just 55 percent, and timely introduction of complementary feeding fell from 52.6 percent in 2015 to 42.7 percent in 2016.

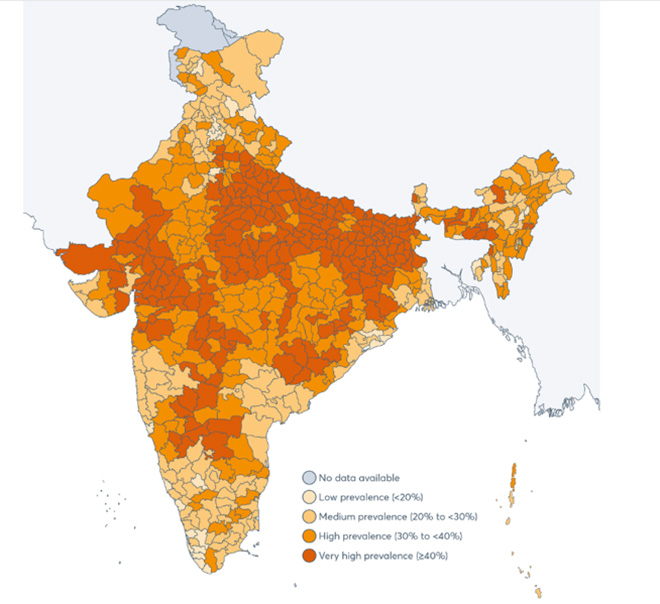

Figure 3 indicates the prevalence of stunting in under-five children at the subnational level. NFHS-4 data shows that India has more stunted children in rural areas than in urban. The prevalence of stunting is double in children born to uneducated mothers as compared to those with 12 or more years of schooling. Stunting shows a steady decline with increase in household income/wealth. There is wide variation in the geographical spread of stunting, with Bihar (48 percent), Uttar Pradesh (46 percent) and Jharkhand (45 percent) having very high rates, while Kerala and Goa (both with 20 percent) have the lowest.

In 40 percent of the country’s districts,[32] stunting levels are above 40 percent. Variation within states and between districts continues to grow: the best district (Ernakulam in Kerala) has only 12.4 percent of its children stunted, while the worst performing one (Bahraich in Uttar Pradesh) has 65.1 percent. Similar variation is observed for wasting of children under five – one district has only 1.8 percent of wasted children, but there are at least seven districts where under five wasting surpasses 40 percent.

Figure 3: Prevalence of stunting among children under five years at subnational level

The Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey 2016-18 (CNNS)[34] shows that stunted, wasted and underweight children under-five children in the eastern region are 34.7 percent, 17 percent,and 33.4 percent respectively. (The figures are, however, an improvement over those of the 2015-16 national survey.) Some states, such as Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh had a higher proportion of stunted children ranging from 37 to 42 percent, while Goa and Jammu & Kashmir had the lowest rates (16 and 21 percent). As for wasting in under-five children, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Jharkhand showed the highest prevalence (20 or more), while Manipur, Mizoram and Uttarakhand had the lowest, of 6 percent each. A higher incidence of wasting (21 percent) was observed in poorest wealth quintile, as compared to highest wealth quintile (13 percent).

Figure 4: Percentage of underweight among children aged 0–4 years by state, India, CNNS 2016–18

Figure 4 shows the incidence of underweight among children under five years across different states. Bihar, Chattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Jharkhand show the highest prevalence. There was also a stark 10 percentage-point difference between rural and urban areas with 36 percent of rural children being underweight compared to 26 percent in urban areas. Both scheduled tribes (42 percent) and scheduled castes (36 percent) recorded a higher percentage of underweight children than the national average of 33.4 percent, while the other backward classes’ (OBCs) matched the average at 33 percent. Its prevalence among children from the poorest wealth quintile was 48 percent while in the richest wealth quintile it was 19 percent.

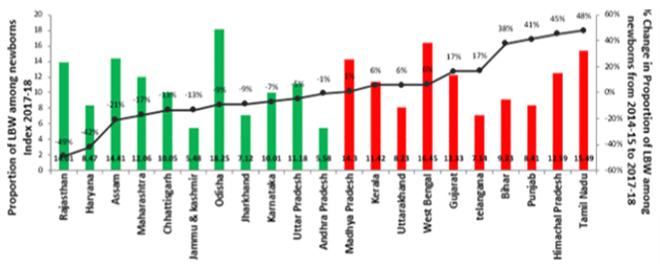

Malnutrition is significantly higher in low birth weight (LBW) children.[36] Nearly half (48 percent) of the larger states saw a falling trend in LBW (Figure 5) between 2014-15 and 2017-18. Odisha saw the highest proportion of newborns with LBW (18.25 percent), followed by West Bengal (16.45 percent) and Tamil Nadu (15.49 percent).[37]

Figure 5: Prevalence of low birth weight in larger states

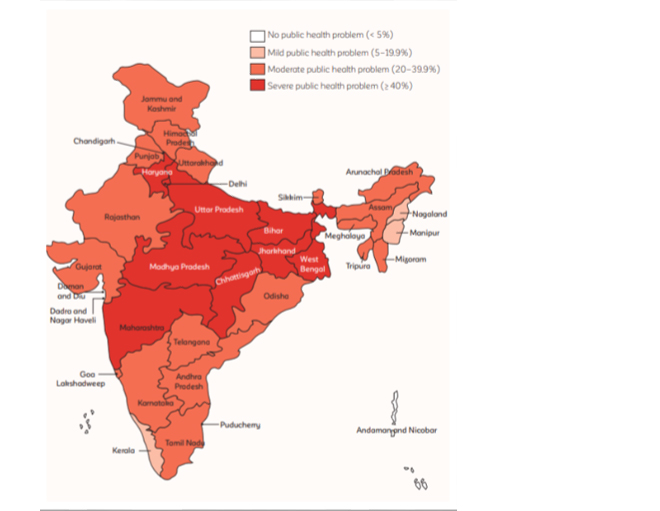

Figure 6 illustrates India’s continued struggle against anaemia. It shows that 41 percent of children under five, 24 percent of school-age children, and 28 percent of adolescents are anaemic. The prevalence of anaemia in women (31 percent) is more than two and a half times that in men (12 percent). The prevalence was highest among scheduled tribes and scheduled castes and was inversely correlated with household wealth. Among pre-schoolers anaemia ranges from 54 percent in Madhya Pradesh to 8 percent in Nagaland. Higher prevalence was observed in children and adolescents from urban areas as compared to their rural counterparts. Anaemia has been characterised a ‘severe public health problem’ in the eastern states of Bihar, Jharkhand, and West Bengal.

Figure 6: Prevalence of anaemia in children under 5 years of age

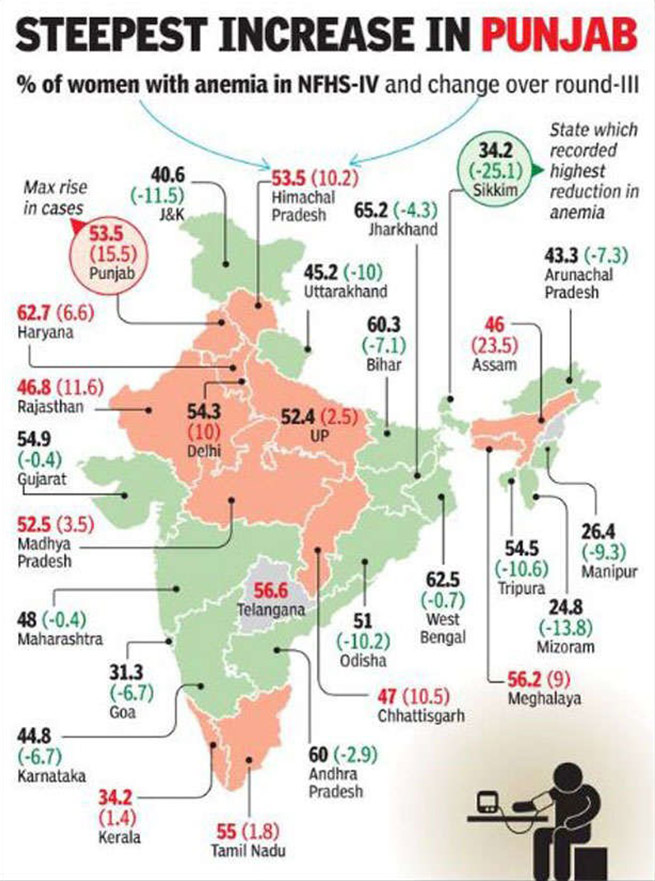

The NFHS-4[40] reveals that nationally 50.4 percent of women in the reproductive age group are anaemic. Figure 7 indicates the percentage of anaemic women in the last two rounds of the national health survey. The eastern states show high occurrence of anaemia; Jharkhand tops with 65.25 percent, followed by West Bengal (62.5), Bihar (60.3 percent), and Odisha (51 percent). All the eastern states have anaemic women above the national average. With a decline of a mere 0.7 percent in anaemic women in the decade 2005-06 to 2015-16, West Bengal is the worst performing state. Jharkhand, where the proportion is highest, saw a decline of 4.3 percent.[41]

Figure 7: Prevalence of anemia in women of reporductive age (15-49 years)

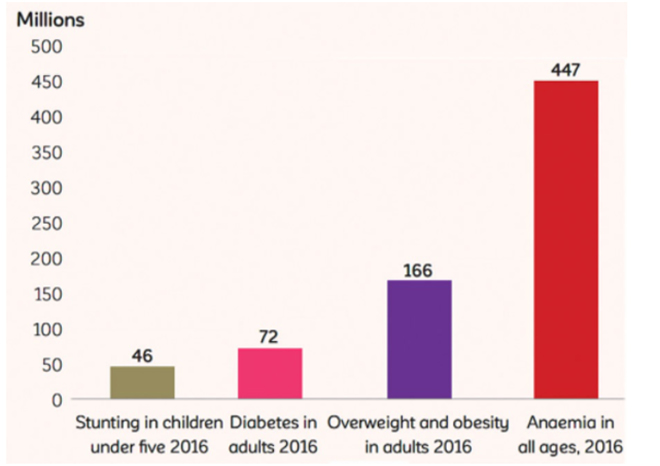

India is struggling to reduce all forms of malnutrition and lagging behind in achieving global standards and its SDG targets. Figure 8 indicates the burden of malnutrition among both children and adults. The burden is highest in the Empowered Action Group states (EAG) of Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha.

Figure 8: Burden of malnutrition among children and adults in India

POSHAN Abhiyaan: Progress So Far

The POSHAN Abhiyaan,[44] launched in 2018, is India’s flagship programme to improve nutritional outcomes for children, pregnant women and lactating mothers. All states and union territories are part of the POSHAN Abhiyaan, except West Bengal. Odisha joined the POSHAN Abhiyaan in September 2019.

POSHAN Abhiyaan’s progress report[45](October 2019-April 2020) takes stock of its on-ground status and the implementation challenges it has encountered at various levels. The report recommends improved complementary feeding using behavioural change, maintaining that this can avert 60 percent of total stunting cases. Investing in education of girls and women, and improved sanitation are other interventions which can avert a quarter of stunting cases.

Odisha’s interventions have shown how convergence of socio-economic factors can lead to holistic nutrition success. Odisha[46] has enhanced service coverage and improved coordination between the ICDS and state health programmes on both the supply and demand side. Figure 9a shows the improvement in nutrition specific intervention in Odisha over a decade. There is marked improvement in breastfeeding counselling, consumption of IFA tablets, Institutional births, and food supplementation, to name a few parameters. There is convergence in delivery of nutrition interventions, such as the Village Health and Nutrition Days – a national programme by which health workers convene a gathering at every village once a month to promote healthcare – and the state’s maternal conditional cash transfer scheme (called Mamata Scheme) by which mothers are paid INR5,000 in two installments provided they follow a set of laid down health practices (Figure 9b).

Figure 9a : Changes in nutrition specific interventions in Odisha, 2006-16 Figure 9b: Convergence of nutrition specific interventions in Odisha, 2016

The graphs indicate that Odisha still needs to increase investment in underlying determinants of malnutrition, such as combating poverty, food insecurity, low education and poor sanitation, to fully support the benefits of nutrition-specific interventions.

Tackling Malnutrition during the Pandemic: State Strategies

The foremost strategy adopted by the Centre to handle nutrition schemes and services during the Covid-19 crisis has been the provision of supplementary food and rations at the doorstep of beneficiaries through anganwadi centres and workers. The life insurance cover for anganwadi workers has been increased from INR 30,000 to INR 200,000 to support the implementation of nutrition provisions. Online training sessions have been organised by the Ministry for Women and Child Development, at which a total of 700,000 beneficiaries have discussed the necessary safety and security protocols for the pandemic and the psychosocial issues it has thrown up. An exit policy is being worked out on opening of anganwadi centres, and to amplify services. The reverse migration that occurred during the pandemic-induced lockdown, leading to many migrant workers and their families in urban areas returning to their villages, has increased the number of beneficiaries that local anganwadi centres have to support. A mobile app is being develop to further buttress the PMMVY, which has reached 1.99 million beneficiaries so far.

Health and nutrition experts have noted how the combined effects of malnutrition, the pandemic, and natural disasters like cyclones have further endangered the health of vulnerable populations. The disruption of supplies and services has accelerated malnutrition, while causing an economic slowdown—which can only worsen if malnutrition increases. Interventions to curb further worsening incidence of malnutrition are needed: nutritional self-reliance, activation of nutritional surveillance, reduction of delays in delivery of nutrition and other services such as treatment for mental health issues. Self-sufficiency is needed in four food groups – rice, lentils, vegetables and fruits, and eggs/fish. Tribal/caste panchayats should be made self-reliant in providing and promoting nutrition. Moreover, minimising the impact of the COVID-19 disaster and increasing productivity by empowering women and vulnerable groups, is imperative.

Research[47] in states such as Odisha, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh suggests that participatory learning helps to reduce the neonatal mortality rate. With home visits included in the participatory learning action agenda, there has been significant improvement in the dietary diversity of women and children. The post-COVID-19 situation has been challenging for food distribution. However, the targeted beneficiaries (children) have been provided with rations at their doorstep, encouraged to eat eggs and practice hand washing.

Jharkhand: Jharkhand has reduced stunting and ‘severe acute’ malnutrition (SAM) in children, as well as anaemia in both children and adults. It has focused on nutrition of adolescent girls and pregnant women, providing accurate interventions at the right age. However, nutritional leadership at the panchayat level needs to be developed, and engagement with agricultural communities increased, to improve nutritional outcomes. Programmes should be implemented at the district levels through local authorities. Jharkhand has started the POSHAN PEHL, focusing on five of its districts to monitor the impact of direct bank/cash transfer on the nutritional status of pregnant and lactating women.

Bihar: Bihar has successfully used a new software introduced in June 2018 called ICDS-Common Application Software (ICDS-CAS) which enables real-time monitoring of nutritional outcomes, to tag beneficiaries, while also organising home visits to deliver services. It has developed model anganwadi centres as centres of e-learning for children. Migrant workers have been enrolled in anganwadi centres and provided with nutritious food (milk and eggs) from state/flexi funds. Initiatives have been taken to improve complementary feeding, and studies shows a 70 percent increase in uptake by families. Almost INR200 crore has been disbursed under the PMMVY in the last three months (April to June 2020). The CNNS shows a decrease in stunting and wasting in Bihar as compared to the NFHS 4.

Odisha: Odisha has looked after its returning migrant population by ensuring provision of nutritious food for them under ICDS. It has been provided food grains during the pandemic. Dry rations, instead of a hot cooked meal, are being delivered to the doorstep of beneficiaries. Pregnant and lactating women have been provided rations. The state has used its anganwadi centres to care for returning migrant labourers.

A study[48] on Household-level food and nutrition insecurity and its determinants in eastern India suggests that the lack of food and nutrition security in eastern India could significantly curtail development in the region. It notes the lack of dietary diversity of food consumption in the eastern states, wherein consumption of necessary foods such as milk, fruits, or non-vegetarian foods is low. It indicates that the calorie deficiency of a household is impacted by socio economic determinants such as age and educational status of the household head, annual per capita expenditure of the household, share of food grain distributed through the public distribution system (PDS) in its cereal consumption, the type of occupation of the family members, their access to formal credit, their ownership of land and livestock and dietary diversity of the food they consumed.

A national Commitment to Action[49] has been made to achieve nutrition security in a concerted, coordinated and effective manner despite the COVID-19 pandemic. The need is for sustained leadership for food and nutrition security, and a collective multisectoral approach to ensure that POSHAN Abhiyaan is being implemented with ambitious targets and accompanying actions. The Commitment to Action aims to ensure adequate financing to deliver essential nutrition interventions at scale while paying close attention to equity. It will accelerate the efforts during the crisis to address food security, including dietary diversity and access to adequate micronutrients, primary health care, safe drinking water, environmental, and household sanitation, along with addressing gender-based issues such as women’s education and delaying age of conception.

Conclusion

Proactive measures are needed to address the longstanding issues of malnutrition and food insecurity. The imperative is to devise structured, time-bound and location-specific strategies with due consideration to the effects of socio-economic factors, and the impact of the pandemic. It is also crucial to create a comprehensive approach that will address the different sectors and dimensions of nutrition. There are two complementary approaches to reducing undernutrition: direct nutritional interventions and indirect multi-sectoral approaches. Direct interventions, such as breastfeeding, complementary feeding and handwashing practices, complement the long-term sustainable multi-sectoral approach.

The states of Odisha, Bihar and Jharkhand have tried innovative approaches that are showing encouraging trends in fighting malnutrition. These need to be sustained and accelerated. Active surveillance, enhancement of resources for nutrition programming, and micro-level participatory planning as well as monitoring, are necessary to achieve progress towards a malnutrition-free India. Strengthening convergence can also aid in better achieving nutrition and health outcomes during these challenging times.

ANNEX

Eastern Regional Workshop on POSHAN Abhiyaan: Fighting Malnutrition amidst the Pandemic

Digital Panel Discussion

31 July 2020

Participants

Aastha Saxena Khatwani, Joint Secretary & MD POSHAN Abhiyaan, Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India

Alok Kumar, Director, Integrated Child Development Services, Government of Bihar

Basanta Kar, Recepient of Global Nutrition Leadership Award and A Transform Nutrition Champion

D.K. Saxena, Director General, Nutrition Mission, Government of Jharkhand

Nirmala Nair, Founder, Ekjut

Purnima Menon, Senior Research Fellow, International Food Policy Research Institute

Rashmi Ranjan Nayak, Joint Secretary-ICDS, Department of Women & Child, Government of Odisha

[1]Swaminathan, Soumya, Rajkumar Hemalatha, Anamika Pandey, Nicholas J. Kassebaum, Avula Laxmaiah, Thingnganing Longvah, Rakesh Lodha et al. “The burden of child and maternal malnutrition and trends in its indicators in the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017.” The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 3, no. 12 (2019): 855-870.

[2] Global Nutrition Report 2018. https://globalnutritionreport.org/reports/global-nutrition-report-2018/

[3] National Family Health Survey 2015-16. http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-4Reports/India.pdf

[4] Global Nutrition Report 2020. https://globalnutritionreport.org/reports/2020-global-nutrition-report/

[5]Georgiadis, Andreas, and Mary E. Penny. “Child undernutrition: opportunities beyond the first 1000 days.” The Lancet Public Health 2, no. 9 (2017): e399. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(17)30154-8/fulltext

[6]FAO 2014. Understanding the true cost of malnutrition.

[7]Panel, Global. “The cost of malnutrition. Why policy action is urgent.” London (UK): Global panel on agriculture and food Systems for nutrition (2016). https://glopan.org/sites/default/files/pictures/CostOfMalnutrition.pdf

[8]Lola Nayar, ‘Budget 2020: Govt Allocating Rs 35,600 Crore For Nutrition-Related Programmes A Welcome Move’. Outlook India, February 1, 2020.

[9]Tingmin Koe, ‘Prioritise children and women: Odisha the first Indian state to exercise nutrition budgeting’, Nutreingredients Asia, February 28, 2020.

[10] Global Nutrition Report 2020

[11] National Family Health Survey 2015-16

[12]World Health Organization. “UNICEF/WHO/The World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates: levels and trends in child malnutrition: key findings of the 2019 edition.” https://www.who.int/nutgrowthdb/jme-2019-key-findings.pdf

[13] Global Nutrition Report 2020.

[14]India ranks 116 in World Bank’s human capital index. The Hindu, 17 September 2020.

[15] Shekar, Meera, Richard Heaver, and Yi-Kyoung Lee. Repositioning nutrition as central to development: A strategy for large scale action. World Bank Publications, 2006. https://www.unhcr.org/45f6c4432.pdf

[16] National Family Health Survey 2015-16

[17]Black RE et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-Income countries. Lancet. 2013; 6: 15-39

[18] National Family Health Survey 2005-06. http://rchiips.org/nfhs/nfhs3.shtml

[19] Global Nutrition Report 2020.

[20] National Family Health Survey 2015-16

[21]Kriti Kapur and Shoba Suri, “Towards a Malnutrition-Free India: Best Practices and Innovations from POSHAN Abhiyaan,” ORF Special Report No. 103, March 2020, Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/research/towards-a-malnutrition-free-india-63290/

[22] National Family Health Survey 2015-16

[23] Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey 2016-18. https://nhm.gov.in/WriteReadData/l892s/1405796031571201348.pdf

[24]World Health Organization. “Nutritional anaemias: tools for effective prevention and control.” (2017). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259425/9789241513067-eng.pdf

[25] National Family Health Survey 2015-16

[26] Annual Report 2019-20. Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India. https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/WCD_AR_English_2019-20.pdf (figures as on 30 November 2019)

[27] Chakrabarti, Suman, Kalyani Raghunathan, Harold Alderman, Purnima Menon, and Phuong Nguyen. “India’s Integrated Child Development Services programme; equity and extent of coverage in 2006 and 2016.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 97, no. 4 (2019): 270.

[28]Mid Day Meal Scheme. Ministry of Education. Government of India. http://mdm.nic.in/mdm_website/

[29]Barkha Mathur, ‘National Nutrition Month: 10 Things To Know About India’s Mid-Day Meal Scheme, World’s Largest School Feeding Program‘, NDTV, September 21, 2020.

[30]Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India. https://wcd.nic.in/schemes-listing/2404

[31]Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution, Government of India. https://dfpd.gov.in/nfsa-act.htm

[32] Menon, P., S. Mani, and P. H. Nguyen. 2017. How are India’s Districts Doing on Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition? Insights from the National Family Health Survey-4. POSHAN Data Note #1. New Delhi, India: International Food Policy Research Institute.

[33] Global Nutrition Report 2020.

[34] Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey 2016-18.

[35] Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey 2016-18.

[36]Rahman, M. Shafiqur, Tamanna Howlader, Mohammad Shahed Masud, and Mohammad Lutfor Rahman. “Association of low-birth weight with malnutrition in children under five years in Bangladesh: do mother’s education, socio-economic status, and birth interval matter?.” PloS one 11, no. 6 (2016): e0157814. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304611953

[37]Kriti Kapur, “How Fares India in Healthcare? A Sub-National Analysis,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 237, February 2020, Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/research/how-fares-india-in-healthcare-a-sub-national-analysis-61664/

[38] Kriti Kapur, “How Fares India in Healthcare? A Sub-National Analysis”.

[39] Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey 2016-18.

[40] National Family Health Survey 2015-16

[41] National Family Health Survey 2005-06.

[42]Shivani Azad. ‘6 states show upswing in anaemia among women’, The Times of India, January 30, 2018.

[43]India still struggling to fight anemia. Eastern Mirror, October 8, 2019.

[44]POSHAN Abhiyan. Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India.

[45]NITI Aayog 2020. Accelerating progress on nutrition in India-what will it take? Third Progress Report.

[46] Avula, R., S. S. Kim, S. Chakrabarti, P. Tyagi, N. Kohli, S. Kadiyala, and P. Menon. 2015. Delivering for Nutrition in Odisha: Insights from a Study on the State of Essential Nutrition Interventions. POSHAN Report No 7. New Delhi: International Food Policy Research Institute.

[47]Tripathy, Prasanta, Nirmala Nair, Sarah Barnett, Rajendra Mahapatra, Josephine Borghi, Shibanand Rath, Suchitra Rath et al. “Effect of a participatory intervention with women’s groups on birth outcomes and maternal depression in Jharkhand and Orissa, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial.” The Lancet 375, no. 9721 (2010): 1182-1192.

[48]Parappurathu, Shinoj, Anjani Kumar, M. C. S. Bantilan, and Pramod Kumar Joshi. “Household-level food and nutrition insecurity and its determinants in eastern India.” Current Science 117, no. 1 (2019): 71-79.

[49] Coalition Food & Nutrition Security. Tackling malnutrition in a pandemic era: A renewed commitment to action for nutrition in India.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr. Shoba Suri is a Senior Fellow with ORFs Health Initiative. Shoba is a nutritionist with experience in community and clinical research. She has worked on nutrition, ...

Read More +

Kriti Kapur was a Junior Fellow with ORFs Health Initiative in the Sustainable Development programme. Her research focuses on issues pertaining to sustainable development with ...

Read More +