-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Devashish Dhar and Manish Thakre, “No Child’s Play: The Enduring Challenge of Creating Child-Friendly Cities,” ORF Issue Brief No. 415, October 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

Often it is the obvious that fails to make a case for itself. India’s two predominant demographic characteristics—a high share of young population, and surging urban populations—call on the country’s urban-policymakers to make cities more child-friendly. Yet the very concept of “child-friendly cities” has yet to be mainstreamed in India’s policy lexicon. This may be understandable given the dire situation of Indian cities, overall: they are mired in serious challenges such as acute pollution, rampant crime, infrastructure deficit, mobility congestion, and environmental hazards. However, the lack of attention on creating child-friendly cities is no longer desirable nor reasonable. Some fundamental statistics make a compelling case for the need to make India’s cities child-friendly.

According to the United Nations (UN) World Urbanisation Prospects report, some 4.2 billion people (55 percent of the world’s population) inhabit the urban areas.1 By 2050, 68 percent of the world’s population will be urban. Three countries—namely, India, China and Nigeria—will account for 35 percent of the growth in the world’s urban population between 2018 and 2050. India is projected to add 416 million to the urban population during the period; China, 255 million; and Nigeria, 189 million.2

Globally, of the entire urban population, one billion are children (23.7 percent).3 By 2050, 70 percent of all the world's children will live in urban areas.4 According to a report from the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA), ‘Status of Children in Urban India Baseline Study 2018’, India is home to 472 million children, comprising 39 percent of its population. Every fourth child in India (27.4 percent) lives in urban areas.5 Given that globally, over one-third of children in urban areas are unregistered at birth,6 there would be many more children in urban areas than is presently known.

These figures leave little room for doubt that building child-friendly cities has become an imperative for India. To be sure, the term itself found mention in the global urban development policy space not too long ago, when the ‘Child-Friendly City Initiative’ was first launched at the UN Habitat II conference in 1996.7 According to Unicef, “A child friendly city is a city or any local system of governance that is committed to fulfilling children’s rights, including their right to influence decisions about their city; express their opinion on the city they want; participate in family, community and social life; receive basic services such as healthcare, education and shelter; drink safe water and have access to proper sanitation; be protected from exploitation, violence and abuse; walk safely in the streets on their own; meet friends and play; have green spaces for plants and animals; live in an unpolluted environment; participate in cultural and social events; and be an equal citizen of their city with access to every service, regardless of ethnic origin, religion, income, gender or disability.”8

What Makes Cities Inhospitable for Children

London-based engineering and design firm, Arup,9 has provided a useful framework for studying the issues pertaining to the creation of child-friendly cities. The same framework can be applied in the Indian context. The following paragraphs outline the most essential considerations in the pursuit of planning and maintaining child-friendly urban spaces.

1. Traffic and congestion. These issues are critical given the amount of time that children spend outdoors to travel to and from their school, play areas, markets, and social gatherings. The roads, footpaths, crossings are essential in making cities safe and inclusive for children. Roads in Indian cities, for one, are occupied by car and other motorised vehicles – a reflection of the lack of thought given to children as they were being planned and built. Consider this statistic: Transport-related injuries ranked 4th as cause of death among five- to 14-year-olds in India in 2016.10

2. High-rise living and urban sprawl. While high-rise residential setups tend to limit the interactions that children can have with their communities, the urban sprawl focuses on car-focused cities. Such living design also reduces the physical activity of children. In slum areas, too, children live in conditions that are not clean, safe and conducive to their overall welfare. Data shows that over eight million children in the age group of 0-6 years live in urban slums.11 A city centred around motorised vehicles, high-rises and urban sprawls all contribute to the constriction of open and green spaces where children can play and socialise. It is not surprising that a survey (2017-18) on school health and fitness in 86 cities across 26 states in India, found that two in every three children in the age group of seven to 18 do not have a healthy body mass index (BMI); and one in every three have inadequate lower body strength.12 The problem of lack of physical activity has only exacerbated during the COVID-19 crisis as schools have remained closed and children are mostly indoors.

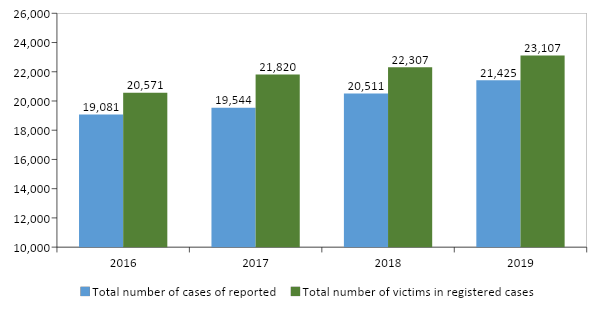

3. Crime, social fear, and risk aversion. Children’s mobility, especially for those in the younger age groups, is determined largely by their parents’ or guardians’ perceptions of the risks in their environment. According to data from the National Crime Record Bureau, the number of cases of crimes reported against children (in violation of provisions of the Indian Penal Code and other laws) in 19 metropolitan cities (cities with >2 million population) increased from 19,081 in 2016 to 21,425 in 2019. The total number of victims in registered cases increased from 20,571 in 2016 to 23,107 in 2019 (See Figure 1).13 Poor infrastructure—including the absence of street lights, footpaths and safe public spaces—pose serious threats to children’s movement in the cities and thereby contribute to the stunting of their development.

Figure 1: Crimes against children, girls and boys (IPC+SLL)14 in 19 metro cities (2016 to 2019)

Source: National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB) report, 2016, 2017, 2018 and 201915

4. Inadequate and unequal access to the city. This involves inequitable access to health and education facilities. For young girls, in particular, the problem can be disproportionately acute. According to Save the Children’s World of India’s Girls (WINGS) 2018 report, traveling in public transport gave the highest sense of risk perception to girls in urban areas (47 percent). This was followed closely by commuting to the local market (41 percent), and using the narrow streets of the neighbourhood or near their school (40 percent). The roads to their school, local market, or private tutor—was also largely perceived as unsafe (37 percent of the respondents).16 According to the Urban and Regional Development Plans Formulation and Implementation (URDPFI) Guidelines,17 there should be one anganwadi18 for every housing area or cluster of 5,000 population.19 These guidelines, however, are not being followed. As Jagriti Chandra noted in an article published in The Hindu, the government of India, in a response to a Right to Information (RTI) query, noted that only seven out of 100 anganwadi beneficiaries in the country are in urban areas and the remaining are in rural.20 While there were a total 79.5 million total beneficiaries of the anganwadi scheme in the country as of 30 September 2019, only 5.5 million were registered at urban anganwadis.21 This is primarily because of an acute paucity of anganwadi centres in urban areas. The outcome is seen in the high incidence of stunting, missed immunisations, and other health issues. For example, according to the 2015-16 National Family Health Survey(NFHS) - 4, 38 percent of India’s urban poor children are stunted.22 Moreover, 36 percent of children in urban areas miss full immunisation; the ratio is as high as 58 percent for the urban poor. The country also has some 2.27 million children in the age group of 0-19 years in urban areas who have some form of disability.23

5. Risk of isolation and intolerance: Single-use neighbourhoods24 restrict the movement of people throughout the day and prevent children from going to such spaces. During natural calamities, for example, children suffer the worst due to their limited physical ability to cope and keep themselves safe.

The other issues that impact children in India’s cities include the lack of age- and gender-disaggregated data on children living in slums and non-slum households; the limited orientation programmes for municipal and planning officials in engaging children in planning and design; and the negligible participation of children in the municipal affairs that directly affect them. A Delhi child rights body has reached out to the Delhi Development Authority to ensure that the Delhi Master Plan 2041 will not neglect to make provisions for the creation of child-friendly spaces in the capital city.25

Child-Friendly Cities: Everyone Wins

26 It cannot be overemphasised that child-friendly cities are a pillar of inclusive societies. The mere presence of children attracts certain stakeholders – schools, higher education institutes, leisure areas, local economic activity, informal employment—which all go a long way in helping create societies that are inclusive and harmonious.

Various examples can be taken from the experience of other cities. There is, for instance, the ‘Camino Imaginado (Imagined Path)’ project in Bogota City, Colombia. This project aims to improve social inclusion for the inhabitants of urban peripheries. Its objective is to promote safe access for students and teachers to schools and rehabilitate youth offenders by providing them jobs with the help of the Institute for the Protection of Children and Youth (IDIPRON). So far, some 40,000 sq.m. of public spaces and park areas have been recovered to provide access to nearly 90 public schools. It has also created 1,300 jobs for local youths.27

In other parts of the world, there are efforts that are focused on safe transportation. One such initiative is the “Safe routes to school” programme in the United States which ensures safe passage for children to walk or cycle to school using a range of measures such as enforcement, improving infrastructure, safety education, and incentives for non-motorised transport.28 In the world after COVID-19, many cities will be moving towards becoming their own versions of the idea of a “15-minutes city”— a new concept that focuses on creating cities where “daily urban necessities are within a 15-minute reach on foot or by bike”.29 Led by Paris, this initiative has the potential to be mirrored in other cities aspiring to be “smart”.

Some cities recognise that the best way to make changes in a city is at the planning level, and are leading the way. In India’s immediate neighbourhood, Dhaka is setting the tone for participatory planning. City authorities, along with the Bangladesh Institute of Planners, are engaging children in promoting child-sensitive urban planning. Elsewhere, several municipalities in Latin America are planning child-friendly infrastructure and services by engaging with children through their Mayor’s office. In Boston, the Mayor is engaging the youth (age 12 to 25) through participatory budgeting. Indeed, it is the first American city in which the youth have been empowered to make decisions regarding a portion of their city’s capital budget.30

There are also examples where an entire suburban area was planned around the needs of children. The Dutch suburb of Houten devised two transportation networks: first is a network of paths for cyclists and pedestrians which forms the core of the city and reaches important buildings and the town centre; and a second is a network for cars, which attempts to keep a distance from the first network. The city has delivered remarkable results on safety, security and health of its citizens. The children can travel for school and leisure without being endangered by the possibility of meeting with a road accident. This, however, is less efficient in terms of greenhouse gas emissions as people have to drive longer if they are using cars.31

Rotterdam has shown remarkable progress by spending resources on creating child-friendly cities. It converted an open space in a city park forest into a nature playground – Natuurspeeltuin de Speeldernis – which gives children a rare opportunity within a city to engage in unstructured play.32 The kids can access biodiversity of “wild” space and take part in associated activities such as camping and rafting.

In India, the lack of safety, particularly for poor urban children is a primary cause of concern, as discussed earlier, when conceptualising child-friendly cities. There are ongoing initiatives in certain areas that focus, for example, on making police stations child-friendly. In Rajasthan’s Dungarpur town, the child-friendly police station has a room that houses toys and books. It is designed to encourage police personnel to be sensitive to the child survivor’s needs and put them at ease if they need to be in the presence of law enforcement agents. Kerala, too, has created its first child-friendly police station; it is targeting to create one in each district.33

In Bhubaneswar, officials have launched the “Socially Smart Bhubaneswar” initiative, under which adolescent girls are being trained in self-defence techniques.34 The city has also joined the Urban95 initiative of the Bernard van Leer Foundation which aims to create cities with the needs of a three-year-old (whose average height is 95 cm, and thus the name).35 This initiative focuses on making changes at the urban planning level. Pune has also recently joined the programme.36

The wider issue of pollution and road accident fatalities is now being addressed at the national level. For instance, the draft National Urban Policy Framework (NUPF) recognises the vulnerabilities being faced by “street connected children” and mentions providing shelter to them.37 The ‘Housing for All’ scheme and national focus on reducing air pollution (such as clean air funding, promotion of e-vehicles in cities, reducing stubble burning) will help make Indian cities safer for children.

Conclusion

Planning at the city level can provide gains for children through some fundamental changes as suggested by Arup in their report.38 For instance, the cities should plan for multiple-use green infrastructure that has utility throughout the year and in all seasons. Copenhagen, for example, is building parks that also serve as ponds during rains.39 They do not only provide spaces for outdoor activities but also acts as a reservoir. Likewise, the planning can provide for spaces wherein people from different generations can spend time. This will make the city healthier and increase trust among stakeholders.

Learning from the experience of other countries, some Indian cities have started closing down roads for vehicles for certain times of the day or even for an entire day in the year.40 41 42 It would be encouraging if the city officials could engage schools and colleges nearby to come and spend their time on these streets – they can organise activities like book fairs, cultural fairs, street art, and food carnivals. The idea is to get children spending more time outside with other community members in a safe environment.

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, when children are having to deal with constraints on learning and playing, and thereby limiting the full use of their faculties, it would do well for India if the Union government, and State and City officials come together to find long-term solutions to the lack of child-friendliness in the country’s cities. Child-friendly cities will bring gains not only for the children themselves, but for the cities. This would bode well for India’s initiatives in turning its urban regions into engines of economic growth.

Devashish Dhar (@dhardevashish) is a Public Policy Specialist with the NITI Aayog. He is a Raisina Young Fellow and IVLP Fellow. Manish Thakre (@manishthakre30) is Head of Urban Programme and Policy at Save the Children India. (The views expressed in this brief are personal.)

Endnotes

[1] United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/420). New York: United Nations.

[2] United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “68% of the world population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, says UN,” 16 May 2018, New York.

[3] Arup,“Cities Alive: Designing for urban childhoods,” December 2017.

[4] Sophie Davies, “Cities go wild with child-friendly design,” This is place, May 30, 2018.

[5] NIUA (2018) “STATUS OF CHILDREN IN URBAN INDIA, BASELINE STUDY, 2018 (Second Edition)” Delhi, India.

[6] Unicef, “The State of the World’s Children 2012: Children in an Urban World,” February 28, 2012.

[7] Caroline Brown, Ariane de Lannoy, Deborah McCracken, Tim Gill, Marcus Grant, Hannah Wright & Samuel Williams (2019) Special issue: child-friendly cities, Cities & Health, 3:1-2, 1-7, DOI: 10.1080/23748834.2019.1682836

[8] Unicef, “Child Friendly Cities promoted by UNICEF National Committees and Country Offices – Fact sheet”, September 2009.

[9] Arup is an independent firm headquartered in London. It provides design, planning, engineering, architectural, consulting and technical services for all aspects of the built environment.

[10] Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME).

[11] “STATUS OF CHILDREN IN URBAN INDIA, BASELINE STUDY, 2018 (Second Edition)”

[12] “STATUS OF CHILDREN IN URBAN INDIA, BASELINE STUDY, 2018 (Second Edition)”

[13] Crime in India (2019/2018/2017 and 2016), National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, http://ncrb.gov.in/

[14] Indian Penal Code (IPC) and Special and Local Laws (SLL)

[15] Crime in India (2019/2018/2017 and 2016), National Crime Records Bureau

[16] Save the Children, “WINGS 2018, World of India’s Girls: A study on the perception of girls’ safety in public places”, 2018.

[17] Urban and Regional Development Plans Formulation and Implementation (URDPFI) Guidelines, 2014, Town and Country Planning Organisation, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. The guidelines were launched in January 2015 with amendments and comprise of two volumes. These guidelines are focused on updating the process of planning and the implementation of plans in the urban areas.

[18] Healthcare centresfor mothers and young children, set up under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) by the Women and Child Development Ministry, Government of India

[19] Town and Country Planning Organization, Ministry of Urban Development, “Urban and Regional Development Plans Formulation and Implementation (URDPFI) Guidelines,” Volume I, January 2015.

[20] Jagriti Chandra, “Only 7 in 100 anganwadi beneficiaries are in cities,” The Hindu, February 05, 2020.

[21] Chandra, “Only 7 in 100 anganwadi beneficiaries are in cities”

[22] Alok Kumar and Khushboo Saiyed, “Does India Need New Strategies For Improving Urban Health And Nutrition?”,Niti Aayog, August 05, 2019.

[23] “STATUS OF CHILDREN IN URBAN INDIA, BASELINE STUDY, 2018 (Second Edition)”

[24] A single use neighbourhood is an area of a city or town that contain single space either residential or commercial/market space. While in the mixed-use neighbourhood encompass an area of a city that contain both residential and commercial/market space.

[25] HT Correspondent, “Ensure Delhi child-friendly spaces in master plan draft: Rights body”, Hindustan Times, June 25, 2019,

[26] Isabella Buber and Henriette Engelhardt, “Children’s impact on the mental health of their older mothers and fathers: findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe”, European Journal of Ageing, 2008 Mar; 5(1): 31–45.

[27] Javier Duarte, “Imagined Path – Camino Imaginado,”

[28] U.S. Department of Transportation, “Safe Routes to School Programs”.

[29] “Welcome to the 15 minutes city”, Financial Times.

[30] Manish Thakre and Manabendranath Ray, “In Need for a National Urban Policy with Child-centered lens,” The India Saga, Opinion, April 26, 2018.

[31] Charles Montgomery, Happy City, Transforming Our Lives through Urban Design (Published November 12th 2013 by Doubleday Canada), pp 359.

[32] Laura Laker, ”What would the ultimate child-friendly city look like?,” The Guardian, February 28, 2018.

[33] Save the Children, “How India’s Police Stations can be made Child-Friendly,” March 5, 2018.

[34] NIUA (2018) ““CHILDREN” IN THE URBAN VISION OF INDIA, 2019” Delhi, India.

[35] Simon Weedy, “Bhubaneswar joins Urban95 Child-Friendly City Movement,” Child in the City, May 31, 2018.

[36] “Pune’s Vision for Streets Puts Children First,” Institute for Transportation & Development Policy (ITDP), January 13, 2020,

[37] “National Urban Policy Framework (2018)”, Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Government of India.

[38] “Cities Alive: Designing for urban childhoods,” December 2017

[39] Francesca Perry, “Copenhagen's public spaces that turn into picturesque ponds when it rains,” The Guardian, January 22, 2016.

[40] Leanna Garfield, “13 cities that are starting to ban cars,” Business Insider, August 5, 2017.

[41] Kumar Manish, “India Experiments with Car Free Sunday Streets and Bus Day to Popularize People Friendly Cities”.

[42] Parvez Sultan, “Ban on motor vehicles in Delhi’s Chandni Chowk; pedestrians, cycle and e-rickshaws to be allowed”, Hindustan Times, August 28, 2018.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Devashish Dhar works as a Policy Specialist at NITI Aayog. He is also a Raisina Young Fellow-elect for Asian Forum for Global Governance 2019 which ...

Read More +

Manish Thakre is a consultant specialising in Climate Action, Resilience, and Inclusive Urban Development. Executive MSc in Cities, London School of Economics and Political Science ...

Read More +