Introduction

In its normative form, development cooperation, also known as development partnership, involves the creation of a cooperative framework for the “promotion of social and economic development of developing countries”.[1] The traditional donor-recipient relationship has now been replaced by partnerships where the actors involved are considered equal. Indeed, development partnerships have become pivotal for catalysing resource mobilisation and leveraging global public goods.[2] The international system is currently suffering from multiple multidimensional crises.[a] These interconnected challenges have amalgamated into what is sometimes called a ‘polycrisis’.[3] Amid such a situation, progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has been steady but fragile, with significant and persistent challenges.[4] Financing for Agenda 2030 has emerged as a major bottleneck, with several developing economies—particularly the least developed countries (LDCs), low-income countries, and the small island developing states (SIDS)—suffering the most. The gap to finance the SDGs widened from US$2.5 trillion in 2020 to a staggering US$4.2 trillion in 2023.[5] A drop in external finance sources (mainly private agencies, remittances, and foreign direct investment) and the diversion of existing resources to tackle the pandemic has impacted the capital outflow in developing countries.

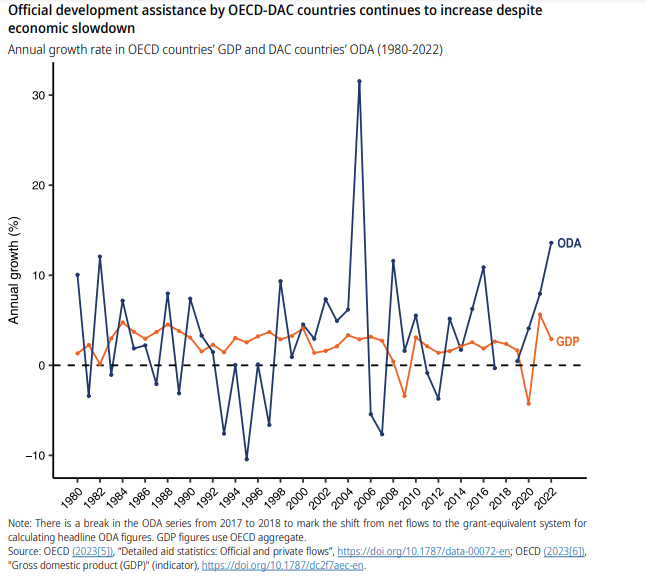

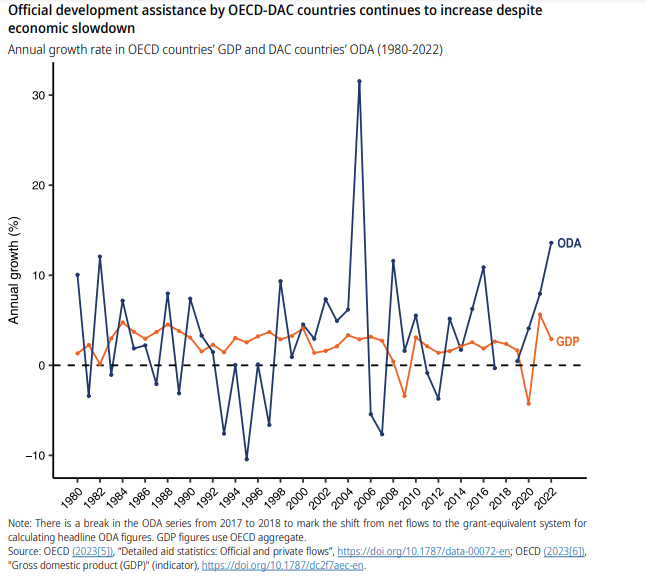

However, these multiple economic and political shocks had a mixed impact on the international developmental cooperation architecture. Despite the drastic drop in global GDP, the volume of Official Development Assistance (ODA) provided by traditional donors—i.e., the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)[b]—increased to its highest level ever in 2020, touching almost US$161 billion.[c],[6] In 2022, the DAC donors provided about US$204 billion, a 13.6 percent increase in real terms from 2021.[7] This reflects a crucial feature of ODA—acting as a shock absorber in crises. Indeed, despite an economic slowdown, ODA by DAC donors experienced its highest growth rates alongside ‘slowing-but-positive-GDP growth’ in the OECD countries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: ODA by OECD-DAC countries

Source: OECD-DAC Report, 2021[8]

According to the OECD, since its inception in 1960, ODA has become a formidable and stable source of external financing for developing countries.[9] However, as seen during the pandemic, utilising ODA as an emergency response measure could reduce funds for long-term developmental needs. Moreover, higher levels of debt and rising debt servicing costs are putting added pressure on LDCs and other developing economies. Although lending through ODA channels does not necessarily compose debts, it automatically indicates an increasing demand for concessional resources. Development cooperation has a strong economic dimension, underscoring its necessity for countering poverty, climate, and food and water scarcity, among other issues.[10] Indeed, several low-income economies rely upon the funding provided by international institutions to tackle their economic struggles. At the same time, many development providers are working on aligning foreign trade with their ODA commitments to enhance results effectiveness. For instance, the Dutch government encourages local businesses to open operational centres in developing countries to facilitate economic development. Here, development cooperation can be viewed as an economic tool.[11] From triggering a flow of investment to building resilience among the vulnerable, experts believe that development cooperation can potentially build viable partnerships between various community stakeholders (such as the private sector, civil society, and sub-national agencies).[12] For instance, the SDG financing gap of US$4.2 trillion can be closed with the increased involvement of private actors.[13]

Importantly, ODA is not free of geopolitical influence.[14] Although the idea of ‘aid’ emerged after the Second World War through the US-led Marshall Plan,[d] it is also an essential component of the interconnected web between economic diplomacy and international relations. However, the modern-day international aid architecture is not simply one country providing resources to another. It represents a highly composite tool of political manoeuvring involving several intentions and interests with varying degrees of impact and potentially detrimental results. Indeed, the great power competition is visibly penetrating the international development landscape, putting developing economies under pressure to navigate the shifting geopolitical currents.[15]

The Indo-Pacific is important in this regard. Given the global tilt towards the region for geopolitical and geoeconomic imperatives, the Indo-Pacific represents a unique case—a combination of vital security stakes and crucial sustainability issues. The continued dominance of a security-based narrative in this region has raised concerns about how nations can effectively cooperate to achieve the SDGs where resources are scarce and capabilities to access these resources are limited. Comprising about 40 countries,[e] home to nearly 65 percent of the world population, and accounting for 63 percent of the global GDP and around two-thirds of world trade,[16] the Indo-Pacific is also witnessing the emergence of several new development policies/strategies targeted towards it as countries aim to strengthen their reach, even as those in the region try to manage this interest.[17]

This brief explores the role of development cooperation as a diplomatic tool in countries’ broader foreign policy narrative in the Indo-Pacific.

Development Partnerships in the Indo-Pacific

Several Global North and South partners have undertaken crucial interventions in the Indo-Pacific in different sectoral areas, including quality infrastructure, community resilience, biodiversity protection, and health.

Global North

Several developed countries in the Global North have supported developing economies for decades. Although their interventions initially focused on poverty eradication and hunger, they moved beyond these domains to address the larger sustainability challenges in the Global South.

- Japan: Although the Indo-Pacific construct may have only recently gained traction in the global developmental landscape, several OECD-DAC donors have long been involved in the region. Japan is a crucial actor in this region, given that former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe first floated the idea of the Indo-Pacific in 2007 for “strengthening the political and economic link among democracies situated in Indian and Pacific Oceans for securing sea lanes and promoting economic prosperity”.[18] As part of the ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’, Japan (through the Japan International Cooperation Agency) focuses on enhancing governance through capacity building,[f] quality infrastructure investment, and enhancing hard and soft connectivity in the region.[19] For example, the Southern Economic Corridor[g] and the East-West Economic Corridor[h] under the Japan-ASEAN Connectivity Initiative,[20] and the Papua New Guinea Electrification Partnership with the US, Australia, and New Zealand will help facilitate the energy needs of 70 percent of the former’s population by 2030.[21]

- Australia: Australia has prioritised the Indo-Pacific, particularly the Blue Pacific, as decisive for long-term peace, stability, and prosperity in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s ODA Budget 2023-24.[22] Giving precedence to building partnerships for recovery and resilience, especially in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, Australia has been diverting its ODA to health, water, education, and social protection systems.[23] Under the Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific, the country doubled its commitment to the Pacific from US$9.9 billion to US$19.87 billion in the 2022-23 budget. It also announced an additional US$900 million as ODA to the October 2022 budget, directed towards Pacific climate resilience and mitigation targets. Moreover, it is providing US$25.5 million to rebuild schools using climate-resilient infrastructure consisting of renewable energy in Fiji; the Australia-Kiribati Climate Security Initiative focuses on strengthening coastal resilience to disasters with an ODA of US$5.6 million; and almost US$20 million is being disbursed to improve access to climate finance and enhance engagement with the carbon markets in Papua New Guinea. Australia is also working with regional integration initiatives such as the ASEAN to develop its Strategy on Carbon Neutrality and provide skills training and technical assistance programmes.[24]

- France: France is a resident power in the Indo-Pacific, with three overseas territories (French Polynesia, Réunion, and New Caledonia) in the region.[25] In 2023, the French Development Agency announced funding of US$222.5 million for the next five years to the region.[26] It has also been working extensively through initiatives such as the International Solar Alliance, promoting collaboration on climate change countermeasures in Indo-Pacific and Africa jointly with Japan,[27] and providing US$200 million in funding through Proparco[i] to support small and medium enterprises in Southeast Asia in manufacturing solar products and systems, among other items.[28] The establishment of the India-France Indo-Pacific Triangular Development Cooperation Fund in July 2023 is an important development towards financing a resilient and sustainable future, especially in the SIDS.[29] The Kiwa Initiative—a multi-donor programme launched in 2021 jointly with the European Union (EU), Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Global Affairs Canada, and New Zealand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade—to strengthen the climate resilience of the Pacific Islands’ ecosystems, communities, and economies through nature-based solutions by protecting, sustainably managing, and restoring biodiversity is also noteworthy.[30] In 2023, France provided additional funding of US$19.7 million, enhancing the overall funding to US$82 million.

- European Union: A crucial development cooperation provider, the EU and its institutions (particularly the Directorate-General for International Partnerships) have stepped up engagement in the Indo-Pacific, especially after the launch of its Indo-Pacific Strategy in 2021.[31] The EU has committed about US$820 million in funding for the 2021-2027 period for the Pacific region, which includes the Pacific Islands countries (PICs),[j],[32] Timor-Leste, and overseas countries and territories.[k],[33], The EU’s presence in the Indo-Pacific is exemplified primarily by the Global Gateway Initiative, which focuses on climate resilience, the green transition (through the Green Climate Fund), ocean governance, digital connectivity, infrastructural development, and the humanitarian aid programme. Attempting to lay a “template for sustainable and trusted connections that works for people and the planet”, the initiative aims to mobilise up to US$328 billion in investments in the digital, climate, energy, health, transport, and education sectors.

- The US: The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has supported developmental initiatives in the Indo-Pacific in disaster preparedness, health, water, democracy, and governance.[34] For instance, in 2021, USAID announced an ambitious target of mobilising US$150 billion in public and private climate finance in the Pacific by 2030.[35] Moreover, it launched the Green Recovery Investment Platform to mobilise US$2.5 billion in private finance for adaptation and mitigation by 2027 by offering incentives and risk apportionment to address the growing climate finance gap. Under the triangular development format, USAID, in collaboration with India’s Ministry of External Affairs Development Partnership Administration II, is working with Fiji to build telemedicine and psychosocial care capacity in disaster-preparedness and post-disaster settings.[36] Furthermore, under the Infrastructure Transaction and Assistance Network launched in July 2018, USAID and other partners aim to catalyse private-sector investment for high-quality infrastructural projects in the Indo-Pacific.[37]

- Germany: Germany presented its policy guidelines for engaging with the Indo-Pacific region in 2020.[38] The increasing significance of this region and China's rising influence has led Germany to realign its interests and foreign policy interventions in the Indo-Pacific.[39] Germany is involved in several programmes, such as climate risk financing, environmental and marine protection, biodiversity, increasing the security resilience of partner countries, cybersecurity, humanitarian assistance, agriculture, health, and sustainable urban development. For instance, the government has partnered with ‘Partners in the Blue Pacific’, an initiative encouraging positive engagement and cooperation between the PICs.[40] To strengthen their resilience towards climate change, Germany has committed to offer comprehensive protection packages tailored to the PICs’ national priorities under the Global Shield against Climate Risks. Further, almost US$76.2 million has been approved as part of the International Climate Initiative to support biodiversity loss, climate action, and adaptation projects in the Pacific Islands. Germany has also committed about US$21.7 million towards the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative started by India, which aims to help the PICs in their journey towards climate adaptation, preservation of biodiversity, achieving energy efficiency, and boosting their resilience against repeated climatic disasters. Furthermore, German development cooperation is expanding its outreach in the region through the triangular mode of interventions. For instance, Indo-German triangular cooperation has introduced pilot projects in potato farming, bamboo production, and agribusiness for women entrepreneurs in Malawi, Ghana, and Cameroon.[l],[41] An ongoing triangular project is also underway in Peru, focusing on agricultural social programmes.[42]

- The UK: The UK came under the scanner in 2021 for slashing its budgetary allocations for aid owing to political and economic restraints, mainly fuelled by the refugee crisis driven by the Ukraine crisis.[43] In its 2023 white paper on international development cooperation, the UK government acknowledged that the negative impacts of climate change will invariably accentuate the challenges of ending extreme poverty.[44] The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office announced a UK-ASEAN Plan of Action (2022-2026) to boost regional cooperation on maritime, connectivity, SDGs, and economic growth in the Indo-Pacific.[45] The FCDO also aims to propel developing economies’ energy transition through Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs), a country-led partnership with developed countries, development finance institutions, civil society, the private sector, and other relevant stakeholders. Through the G7, the UK has signed JETPs with Indonesia and Vietnam to run technical assistance and capacity-building programmes. As listed under the UK-India Roadmap 2030, the UK government supports India’s clean energy initiatives to tackle climate change and achieve the SDGs.[46] The launch of the Green Grids Initiative (GGI) under the One Sun One World One Grid in 2021 is a case in point. With a target of unveiling “the full potential of clean power globally with the help of interconnection of electricity grids across regions and communities, including mini-grids and off-grid solutions”, the GGI aims to provide access to energy for all. The UK government is also inclined towards the triangular partnerships format to scale up financing for SDGs, such as the UK-India Global Innovation Partnership programme that attempts to “foster, transfer and boost demonstrated and sustainable, climate-smart innovations from India to third countries” for the good of the larger sustainability narrative.[47]

Global South

South-driven partnerships have dominated the development narrative since the 2000s. Several countries from the Global South, like India, China, Indonesia, and South Africa, are driving the conversation on development partnerships, offering an alternative to the OECD-DAC donor model. Under South-South cooperation, many countries emerge as dominant players in establishing large-scale connectivity models, bolstering inclusion at multilateral forums, and fostering diversified partnerships.[48] Indeed, the role being undertaken by the Global South is paving the way for more inclusive global interactions alongside the readjustments of global agendas. Underlying these shifts is the challenge being posed to current aid orthodoxies.[m],[49]

- India: India’s Development Partnership Administration (DPA)—its main implementing body for matters related to development cooperation—performs its activities under three main pillars: lines of credit (LOCs), grants and loans, and capacity building under the Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation programme. As per its 2023 budgetary allocations, India has committed US$48.3 million to the Maldives, US$12.09 million to the Seychelles, US$18.1 million to Sri Lanka, and US$10.88 million to Mauritius as grants and loans. It has also allocated about US$55.78 million to Fiji, US$100 million to Papua New Guinea, US$691.6 million to Vietnam, and US$226.23 to Laos till September 2023.[50] India’s recent tilt towards the PICs is noteworthy. The historic first visit by an Indian prime minister to Papua New Guinea in 2023 came at a crucial juncture.[51] India’s foreign policy objectives are now reconfiguring to include the Pacific Island countries; for instance, in May 2023, India jointly hosted the Third Summit of the Forum for India-Pacific Islands Cooperation with Papua New Guinea. At the summit, India unveiled the 12-step action plan to solidify its development partnership with the PICs and consolidate the shared vision of a free, open, and prosperous Indo-Pacific.[52] India is a dialogue partner at the Pacific Islands Forum. Several Indian organisations are also implementing people-centric projects at the grassroots level. For example, the Bhagwan Mahaveer Vikalang Sahayata Samiti (Jaipur Foot Organisation) organised an artificial limb fitment unit in Fiji in collaboration with the Fijian health ministry in 2011. Other efforts by the Centre for Development and Advanced Computing,[n] include establishing a Centre of Excellence in IT at the University of South Pacific in Alofi, the capital of Niue, in coordination with the Centre for Development of Advanced Computing of India; setting up a Centre of Excellence in Information Technology at the National University of Samoa, Apia; creating a Centre of Excellence in IT in the Solomon Islands National University; establishing the Information Technology Innovation Lab Project in the Oẻ-Cusse region of Timor-Leste, and the inclusion of a US$150,000 grant in Fiji (as part of the India-UN Development Partnership Fund) for updating IT facilities at the Mahatma Gandhi Memorial High School.[53]

- China: China is the largest trading partner in the Indo-Pacific.[54] Its growing footprint in this geographical space can be attributed to two reasons: the shifting balance of power with the relative decline of the US and the mounting developmental challenges in the region. China has been aiming to ramp up its engagement with several multilateral organisations, including the UN, to align its development partnership model with Agenda 2030. The Indo-Pacific forms an essential component of the sustainability map. China’s developmental cooperation model is embedded in augmenting its visibility across the developing regions of Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, parts of Europe, and the Indo-Pacific, with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as the crucial medium. Explicitly promoting Beijing’s strategic intent, the BRI has become “a magnet of controversy and criticism”, termed a “debt-trap” diplomacy tool. Under this umbrella infrastructure project, the Chinese development cooperation model exhibits its eagerness to internationalise[55] the ensuing heavy debt burdens for several vulnerable economies. Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port is an oft-cited example, as is the severe financial distress faced by 22 African countries.[56] Although the launch of the Global Development Initiative and Global Security Initiative[o] might indicate an effort to move towards a “new development paradigm”,[57] China’s development cooperation model showcases “market imperialist designs” through the BRI for capturing the factor and product markets.[58]

- Indonesia: Indonesian development cooperation efforts can be understood from the perspective of South-South cooperation. For instance, in 1946, Indonesia sent almost 500,000 tons of rice to a famine-stricken India.[59] This early humanitarian assistance helped the country gain recognition from its southern partners and further solidified its position on the global map. As a founder of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), Indonesia is known for bolstering its technical cooperation among developing countries in sectors like agriculture, fisheries, and family planning. In 1995, Indonesia established a NAM Centre for South-South Technical Cooperation to focus on poverty alleviation and developing small and medium enterprises, agriculture, health, environment, and information and communication technologies. Moreover, Indonesia has been pursuing the triangular mode of cooperation for a long time;[60] by working closely with a developed country and multilateral forums, Indonesia has been supporting projects on knowledge transfer, sharing of expertise, capacity building, and related activities. Between 2000 and 2013, Indonesia contributed approximately US$49.8 million to South-South and triangular cooperation.[p],[61] Furthering this model to the Indo-Pacific, Indonesia has underscored its commitment towards the PICs through the ‘Bali Message for Development Cooperation’, announced at the Indonesia-Pacific Forum for Development in December 2022.[62]

Strategic Fundamentals of Development Cooperation

Foreign policy is not conducted in a vacuum. It operates in a complex web, navigating real and perceived strategic interests, building capabilities against real and calculated pressures, creating, and preserving a friendly system of global politics, and projecting power for political and economic advantages. In the international development space, states negotiate to define their position and identity while seeking to advance their interests through direct actions or by shaping global norms and regulations.[63] As diplomatic engagements cannot be independent of strategic interests, development cooperation is linked with advancing and consolidating compatible agendas.

Recognising that strategic agendas are functional and valuable rather than inimical is imperative to better assess the motivations and effectiveness of development cooperation through the nuanced understanding of attendant strategic undercurrents. Political drivers (or factors and influences within the political sphere that shape the decision-making and actions of governments, political leaders, and institutions) are not ill-disposed or unethical and do not make aid ineffective. On the contrary, they are pivotal in determining aid effectiveness and whether it successfully achieves its targeted goals. The intersection of development cooperation and geopolitical interests is a complex but integral aspect of contemporary international relations. Development partners—donors and recipients—pursue geostrategic and commercial interests through foreign aid.[64] Indeed, geostrategic agendas are “a detailed knowledge of institutions and organizations involved in cooperation, and asking searching questions about who initiates and negotiates the parameters of the projects; what financial, managerial and administrative arrangements are established within and across the different sites of the partnership; what monitoring and evaluation procedures are established, and on whose terms”.[65] This provides a comprehensive understanding of international relations, where the interplay of interests shapes the landscape of development cooperation.

Therefore, strategic underpinnings serve to level the playing field of development cooperation in several ways. First, geopolitical developments over the last decade have warranted increased levels of partnership and cooperation mechanisms, particularly in geographies like the Indo-Pacific. This region has witnessed the need to balance strong polarities. A vital way of doing so is via development cooperation modalities, underscoring its deeply political nature. In 1996, the OECD adopted a strategy called “Shaping the 21st Century: The Contribution of Development Co-operation”[66] that acknowledged the role of “strong self-interest” of donor countries in the development agenda, underscoring the benefits to donor and recipient countries rather than only the recipient country. Development cooperation has changed in recent years, particularly in how policymakers talk about development goals and how it affects developing countries. Crucially, there has been a shift from helping developing countries to focusing on mutual benefits for all those involved. Historically, various motivations have underpinned development cooperation, but the current trend is distinct in its explicit acknowledgement of these motivations. Consequently, contemporary policies are framed to portray these diverse interests as opportunities for ‘win-win’ scenarios rather than as conflicting objectives, advocating for a development agenda that benefits donors and recipients. This shift in political discourse, which shapes legal frameworks and accountability systems, has implications for public oversight and independent assessments, which traditionally have been focused primarily on evaluating the benefits conferred to developing countries.

A more comprehensive articulation of the entire spectrum of goals within development cooperation could enhance the evaluation process in this evolving context. From this perspective, outcomes previously categorised as ‘unintended’ (benefits accruing to the donor country) in the context of traditional development objectives might be seen as intentional or foreseeable when viewed through the lens of mutual benefit. The US, for instance, considers development policy as a mechanism to combat poverty, strengthen bilateral relations, and safeguard its security and commercial interests.[67] This is arguably also applicable in the case of other donor countries, with differences in the interests to be protected.

Second, alongside the recognition of mutual benefit, changes in the language used in the development cooperation narrative demonstrate the sensitivities characterising cooperation and the caution against hierarchical connotations of the traditional donor-led models. This sensitivity has strengthened with the evolution of development cooperation. For instance, terms like ‘donor’ and ‘recipient’ are now primarily eschewed in favour of the term ‘partner’ countries to identify those providing and receiving aid. For instance, India firmly rejects the use of the term ‘donor’ due to its “western” and “paternalistic” implications.[68] Similarly, the term ‘development partner’ is accepted over ‘foreign aid’, particularly by the Global South. Indeed, the term development partner “refers to a wider set of partnerships and practices often more closely integrated with trade, investment, and geopolitical interests, and sometimes situated within very different ideological and discursive frameworks to foreign aid”.[69]

Third, with middle-power countries increasingly willing and, more importantly, able to assume an active role in global affairs, many regions worldwide are undergoing a re-articulation of power. These countries are aspirational and have unique experiences and expertise that they are keen to share with other transition countries. South Korea and Taiwan, for instance, note that their experiences of transitioning to democracies and industrial modernisation can inform the experiences of others.[70] Such exchanges are vital, but aspirational states may also seek cooperative mechanisms to expand their foreign policy outreach (similar to how South Africa positioned itself as a leader in peace-building and post-conflict reconstruction following its transformation from apartheid to democratic governance). India, too, has been offering low-cost developmental solutions and sharing technical and capacity-building experiences with other developing countries. Triangular partnerships are essential in such instances. Although this form of development partnership is significant, strategic concerns cannot be delinked. Such partnerships illustrate uneven power relations, resulting in the protection and promotion of the interests of the donor country rather than the beneficiary.[71]

Debates on the Development Diplomacy Approach

Development cooperation is not just about policy but also about politics.[72] Employing development cooperation as a tool of diplomacy can cater to the larger global good, offering a roadmap for achieving developmental goals. The achievement of developmental goals is particularly vital for several Global South countries looking to fulfil their developmental needs. The accommodation of geostrategic and geoeconomic interests has become integral for establishing development partnerships. While it can be an effective means to foster global relations and advance mutual interests, several debates associated with employing geostrategic and geoeconomic interests are particularly pertinent in the context of the Indo-Pacific.

First is the concern of conditionalities and limits to sovereignty. Donor countries may impose specific policy prescriptions on recipient nations in exchange for their assistance.[q] While conditions can promote good governance and accountability, they may also raise questions about the right of sovereign states to determine their policies and priorities. This tension between donor expectations and recipient sovereignty could lead to diplomatic friction. A prominent example is China’s BRI, where several infrastructure projects are tied to conditionalities, debt sustainability, and even sovereignty. In 2018, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s government reviewed several Chinese-backed infrastructure projects, including the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) and two gas pipelines, citing concerns over high costs and potential national debt implications. Malaysia eventually sought to renegotiate terms and conditions[73] to align with its economic interests. Similarly, several PICs have received Chinese aid and investment that has facilitated infrastructural development but also raises questions about the long-term implications for debt sustainability and sovereignty.[74] For instance, in 2023, David Panuelo, the then outgoing president of the Federated States of Micronesia, spotlighted the “political warfare” induced by China over Taiwan in the Pacific Islands. This shows that China’s development partnership outlook towards the Indo-Pacific is strategically inclined to secure the allegiance of the small island nations.[75]

Second, an overreliance on foreign aid can undermine a recipient nation's efforts to build self-sufficient, independent economies. A heavy reliance on external assistance may hinder the development of the domestic industries and institutions necessary for long-term growth. It can create a dependency dynamic that may persist even after the cessation of aid. Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port is a relevant example. The project resulted in a significant debt burden for Sri Lanka, with the country being forced to lease the port to a Chinese state-owned company to alleviate its debt in 2017,[76] illustrating how large-scale projects, while initially promising economic development, can lead to financial dependence on external actors. It also highlights debt sustainability challenges and the potential impact on a country's long-term economic stability. Indonesia's efforts to develop its infrastructure, such as high-speed railways through the BRI, have similarly spurred discussions about the balance between economic development and long-term sustainability.[77]

Third, the infusion of large sums of foreign aid can also result in implementation delays, lack of clarity on the financial structure, and other administrative hurdles in beneficiary countries. Resources may also be diverted from their intended purposes due to the mismanagement or misallocation of funds. This undermines the effectiveness of development projects and erodes trust between donor and recipient nations. An illustrative example is the triangular format of partnerships. Involving three partners on different development spectrums, the triangular format may often be prone to a lack of coordination and clarity on procurement rules, resulting in high transaction costs.[78]

Fourth, in certain instances, the use of development cooperation as a diplomatic tool can be viewed through the lens of neocolonialism—as perpetuating power imbalances, with donor countries wielding significant influence over recipient nations. This perception can strain diplomatic relations and generate public resistance to foreign aid. For instance, while the BRI aims to promote economic development and connectivity through infrastructure projects across Asia, Africa, and Europe, it has also faced criticism for its potential neocolonial implications.[79] Critics argue that the BRI may lead to a form of economic dependency on China, as recipient countries may become heavily indebted to Chinese financiers. This could give China undue influence over recipient nations' political and economic affairs, resembling a neocolonial relationship where a powerful nation exerts control over less powerful ones.

Similarly, the allocation of special drawing rights (SDRs) by the International Monetary Fund during the COVID-19 pandemic has also raised some concerns about neocolonial tendencies. Some argue that the distribution of SDRs may disproportionately benefit more powerful economies, potentially perpetuating existing global economic imbalances.[80] This perception has sparked discussions about the need for more equitable and inclusive approaches to international financial cooperation. At the same time, recipient countries have also been cautious about potential neocolonial aspects of development cooperation. For example, during negotiations with global financial institutions, countries like Brazil and India[81] have advocated for more equitable terms and a greater say in designing and implementing development projects. They seek to ensure that aid and cooperation agreements are based on mutual respect and shared benefits rather than reinforcing power imbalances reminiscent of colonial-era relationships. For example, during the 2021 BRICS Academic Forum, Indian Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar underlined the necessity of establishing “human-centric globalisation” as a hallmark of the post-pandemic world order. He stated, “India is a constructive contributor to the efforts to create such an international order by sharing the developmental experience with partner countries in the Global South; undertaking humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations, particularly during the pandemic; through initiatives such as the International Solar Alliance (ISA) and the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI); and by acting as a first responder (through Vaccine Maitri) and net security provider in its diplomatic environment.”[82]

Fifth, interventions through development cooperation can sometimes inadvertently contribute to governance challenges. Well-intentioned projects may have unforeseen consequences, potentially exacerbating existing tensions or creating new issues in the recipient country. Also, if the inherent political, social, and economic impediments are not considered, development cooperation can have lower aid effectiveness. Consider the PICs[83] that have long depended on external assistance for their developmental needs. However, effective aid delivery depends on factors such as democracy deficit, high civil and political freedoms, and the larger governance milieu. To address the concern of dependence and sustainability, there has been a growing emphasis on fostering economic diversification and building the local capacity of the PICs. For instance, initiatives that empower civil society organisations and local communities to participate in monitoring and oversight processes are crucial in reducing barriers to effective aid delivery.

Notwithstanding these challenges, development cooperation, when judiciously administered, becomes an instrumental agent in catalysing sustainable economic growth. The imperative for development cooperation emanates from its profound benefits in enhancing human welfare, propelling economic progress, fostering social justice, and fortifying global stability by empowering nations to surmount developmental barriers. As countries grapple with the complex challenges of the 21st century, the continued commitment to and expansion of development cooperation emerges not merely as a moral obligation but as an astute strategic imperative in navigating the intricacies of our interconnected world.

Given its geographic expanse, the Indo-Pacific is susceptible to various vulnerabilities, such as natural disasters, economic shocks, and security threats. Development cooperation is paramount to mitigate these risks by bolstering disaster preparedness, providing critical infrastructure, and augmenting capacity-building efforts. The Indo-Pacific also faces various transnational challenges, such as climate change, environmental degradation, and illicit trade. Development cooperation is critical to confronting these predicaments by helping nations in the region mount collective responses and amplify their capacity to address complex interlinked challenges.

Thus, efforts should be made to ensure a comprehensive understanding of recipient countries’ political, social, and historical contexts by conducting conflict assessments, engaging with local stakeholders, and ensuring that development initiatives are inclusive and sustainable.

Conclusion

The politics of development cooperation encompasses a complex interplay of interests, ideologies, and power dynamics between the partner countries. It is a multifaceted arena where geopolitical, geoeconomic, and geostrategic considerations converge with the imperative to address global challenges.

Development cooperation is a tangible expression of a nation’s broader foreign policy vision. Through this prism, countries leverage aid as a multifunctional instrument to further their strategic and national interests. The deployment of aid serves several functions—fortifying diplomatic relations, enhancing economic ties, and extending a nation's influence across key strategic locations. This use of aid is not a neutral act; it carries the weight of political intentions and often reflects a country's ambition to project its soft power.

The political nuances of development cooperation are particularly evident in geopolitically sensitive areas such as the Indo-Pacific. Here, a country like India navigates the complexities of maritime geopolitics using development cooperation to cement its position as a regional power while contributing to regional stability and prosperity.

The dynamics of international development cooperation have significantly shifted in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly with the emergence of the Global South. This change signals a gradual decentralisation of power and influence, with countries from the Global South becoming recipients, donors, and partners in development.

In this evolving landscape, the politics of development cooperation is influenced by a myriad of factors. The efficacy of aid is scrutinised through the lens of its impact and sustainability, with governance challenges within recipient countries bringing to the fore questions of transparency and accountability. The spectre of neocolonialism often looms over the exchange of aid, with concerns about the imposition of external values and priorities on recipient nations. Finally, conditionalities attached to aid raise debates about the infringement on sovereignty and the autonomy of nations in directing their development paths.

These elements underscore the reality that development cooperation is a field marked by negotiation and contestation under the broader cooperation mandate. As such, it is an evident microcosm of the broader interplay of international relations, reflecting an interconnected world’s aspirations, challenges, and complexities.

Endnotes

[a] Crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change impacts, and conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine have resulted in food and energy insecurity, surging inflation, and increased debt burdens.

[b] The DAC was formed in 1960 as an international grouping of traditional development providers. Currently, it consists of 32 countries/unions: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czechia (or Czech Republic), Denmark, the European Union, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the US.

[c] Notably, although there is no automatic relationship between ODA levels and GDP growth, it has been used for the purpose of explanation by the OECD.

[d] Notably, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, an arm of the World Bank, Oxfam, the Centre for American Relief in Europe, and the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency.

[e] Since there is no commonly agreed-upon definition of the Indo-Pacific, it is difficult to state the exact number of countries in the region. Each country defines and demarcates the region according to its own geographical interests and territorial positioning. Geospatially, the Indo-Pacific is broadly understood to cover the interconnected space between the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

[f] In 2020, Japan announced capacity-building projects for 1,000 individuals over the next three years.

[g] This corridor involves the refurbishment of the national road No. 5 crossing Cambodia and the construction of a highway crossing southern Vietnam.

[h] This corridor involves the construction of roads and bridges between Mawlamyaing and Kawkareik in southeast Myanmar and the refurbishment of national road no. 9 in central Laos.

[i] Proparco is a subsidiary agency of the French Development Agency, focusing on private sector development.

[j] Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Republic of Marshall Islands, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu.

[k] The overseas countries and territories are in the Atlantic, Antarctic, Arctic, Caribbean, and Pacific regions. They include Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, French Polynesia, French Southern and Antarctic Territories, Greenland, New Caledonia, Saba, Saint Barthélemy, St. Eustatius, Sint Maarten, St. Pierre and Miquelon, Wallis, and Futuna. Although not completely sovereign, they depend, to varying degrees, on Denmark, the Netherlands, and France. They also have wide-ranging autonomy in areas of health, economics, home affairs, and customs.

[l] Germany has included Malawi, Ghana, Cameroon, and Peru in its Indo-Pacific strategy and these initiatives fall under its Indo-Pacific programmes.

[m] Aid orthodoxies refer to the systemic flaws observed in the traditional development cooperation models led by the advanced economies. These include inherent biasness and inequalities towards certain interventions which aim to leverage the interests of the development provider. One of the major loopholes include treating the beneficiary as a subsidiary rather than as an equal or partner in a development cooperative framework.

[n] A research and development wing of India’s Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology.

[o] Launched in 2021, the Global Development Initiative and the Global Security Initiative aim to recalibrate and redefine China’s outlook towards development cooperation and sustainable development.

[p] This is the latest figure available on the public portal.

[q] For the purposes of distinguishing between countries providing aid and those receiving it, the terms ‘donor’ and ‘recipient’ are used in this section.

[1] Sachin Chaturvedi et al., The Palgrave Handbook of Development Cooperation for Achieving the 2030 Agenda (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021).

[2] Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “International Development Cooperation,” United Nations, https://financing.desa.un.org/topics/international-development-cooperation

[3] Kate Whiting and HyoJin Park, “This is Why ‘Polycrisis’ is a Useful Way of Looking at the World Right Now,” World Economic Forum, 2023, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/03/polycrisis-adam-tooze-historian-explains/

[4] United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, “Partnerships: Why They Matter,” United Nations Office of Sustainable Development, 2020, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/17_Why-It-Matters-2020.pdf

[5] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, “Closing the SDG Financing Gap in the COVID-19 Era,” United Nations Development Programme, https://www.oecd.org/dev/OECD-UNDP-Scoping-Note-Closing-SDG-Financing-Gap-COVID-19-era.pdf

[6] Yasmin Ahmad and Eleanor Carey, “Development Co-operation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of 2020 Figures and 2021 Trends to Watch,” OECD Library, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/e4b3142a-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/e4b3142a-en

[7] Eleanor Carey, Harsh Desai, and Yasmin Ahmad, “Tracing the Impacts of Russia’s War of Aggression Against Ukraine on Official Development Assistance (ODA),” OECD, 2023, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/5096b978-en/images/pdf/dcd-2023-413-en.pdf

[8] OECD, “Shaping a Just Digital Transformation”

[9] Ahmad and Carey, “Development Co-operation During the COVID-19 Pandemic”

[10] “Dutch Development Policy,” Development Cooperation, Government of the Netherlands, https://www.government.nl/topics/development-cooperation/the-development-policy-of-the-netherlands

[11] Kristalina Georgieva, “The Time is Now: We Must Step Up Support for the Poorest Countries,” International Monetary Fund, March 31, 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/03/31/the-time-is-now-we-must-step-up-support-for-the-poorest-countries

[12] Jorge A. Perez-Pineda and Dorothea Wehrmann, “Partnerships with the Private Sector: Success Factors and Levels of Engagement in Development Cooperation,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Development Cooperation for Achieving the 2030 Agenda (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-57938-8_30

[13] Arun Asok, “Bridging the SDG Financing Gap Through First-Time Fund Managers,” International Institute for Sustainable Development, June 21, 2023, https://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/guest-articles/bridging-the-sdg-financing-gap-through-first-time-fund-managers/

[14] Perez-Pineda and Wehrmann, “Partnerships with the Private Sector: Success Factors and Levels of Engagement in Development Cooperation”

[15] Cynthia Liao and Bernice Lee, “The Geopolitics of Development,” Chatham House, 2022, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2022/12/building-global-prosperity/03-geopolitics-development

[16] Mohammad Masudur Rahman, Chanwahn Kim, and Prabir Dey, “Indo-Pacific cooperation: What do Trade Simulations Indicate?” Journal of Economic Structures (2020), https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-020-00222-4

[17] Cleo Paskal, “Indo-Pacific Strategies, Perceptions and Partnerships: The View from Seven Countries,” Chatham House, 2021, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/2021-03-22-indo-pacific-strategies-paskal.pdf

[18] Shinzo Abe, “Confluence of the Two Seas” (speech, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, August 22, 2007), https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/pmv0708/speech-2.html

[19] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Japan’s Effort for a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/100056243.pdf

[20] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Japan-ASEAN Connectivity Initiative,” 2020, https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/100114591.pdf

[21] Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific, “Papua New Guinea Electrification Partnership,” June 30, 2020, https://www.aiffp.gov.au/news/papua-new-guinea-electrification-partnership

[22] Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australian Government, Australia’s Official Development Assistance Budget Summary 2023-24, https://www.dfat.gov.au/about-us/corporate/portfolio-budget-statements/australias-official-development-assistance-budget-summary-2023-24

[23] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Australian Government, Australia’s New International Development Policy and Development Finance Review, 2023 https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/penny-wong/media-release/australias-new-international-development-policy-and-development-finance-review

[24] “ASEAN Capacity Building Roadmap for Consumer Protection 2025,” ASEAN, 2020, https://asean.org/asean-capacity-building-roadmap-for-consumer-protection-2025/

[25] Government of France, France’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/en_dcp_a4_indopacifique_022022_v1-4_web_cle878143.pdf

[26] Nur Asena Erturk, “France’s Macron Denounces ‘New Imperialisms’ in Indo-Pacific Region, Oceania,” Anadolu Agency, 2023, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/frances-macron-denounces-new-imperialisms-in-indo-pacific-region-oceania/2955973

[27] Japan International Cooperation Agency, “Signing of the Renewed Memorandum of Cooperation with the French Development Agency: Promoting Collaboration on Climate Change Countermeasures in the Indo-Pacific Region and Africa,” 2023, https://www.jica.go.jp/english/information/press/2023/20230425_10e.html

[28] “How Proparco is Supporting French Strategy in the Indo-Pacific Region,” Proparco, February 16, 2023, https://www.proparco.fr/en/actualites/how-proparco-supporting-french-strategy-indo-pacific-region

[29] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “India-France Indo-Pacific Roadmap,” https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/36799/IndiaFrance+IndoPacific+Roadmap

[30] Agence Française de Développement, Government of France, https://www.afd.fr/en/actualites/communique-de-presse/kiwa-initiative-launches-projects-contributions-climate-resilience-pacific-region

[31] Global Gateway, “EU Indo-Pacific Strategy,” 2023, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EU%20Indo-pacific.pdf

[32] European Union External Action, “Pacific,” https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/pacific_en;

[33] European External Action Service, “ASIA and the PACIFIC Regional Multi-Annual Indicative Programme 2021-2027,” European Union, https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-01/mip-2021-c2021-9251-asia-pacific-annex_en.pdf; “European Union Action in the Pacific,” European Union, 2023 https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EU%20Action%20in%20the%20Pacific%20-%20factsheet.pdf

[34] United States Agency for International Development, United States Government, https://www.usaid.gov/pacific-islands/our-work

[35] United States Agency for International Development, “Pacific Islands Regional Profile,” United States Government, 2022, https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-05/2022_Pacific_Islands_Regional_Profile.pdf

[36] USAID, “US and India Promote Health Collaboration Indo-Pacific Region,” 2023, https://www.usaid.gov/india/press-releases/may-05-2023-us-and-india-promote-health-collaboration-indo-pacific-region

[37] USAID, “Advancing Sustainable Infrastructure in the Indo-Pacific Region,” 2023, https://2017-2020.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1861/USAID_ITAN_Fact_Sheet_080719.pdf

[38] Federal Foreign Office, “The Indo-Pacific Region,” https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/en/aussenpolitik/regionaleschwerpunkte/asien/indo-pacific/2493040

[39] Tarveen Kaur, “Growing German Engagement in the Indo-Pacific,” Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi, 2022, https://www.icwa.in/show_content.php?lang=1&level=1&ls_id=8783&lid=5742

[40] The Federal Government, Progress Report on the Implementation of the Federal Government’s Policy Guidelines for the Indo-Pacific in 2023, https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/2617992/61051683e7e1521583b3067fb3200ad8/230922-leitlinien-indo-pazifik-3-fortschrittsbericht-data.pdf

[41] Knowledge and News Network, “Indo-German Cooperation Yields Success in Sustainable Development Projects in Five Nations, 2023, https://knnindia.co.in/news/newsdetails/sectors/others/indo-german-cooperation-yields-success-in-sustainable-development-projects-in-five-nations

[42] Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury, “India Partners with Germany to Deliver Development Projects in Benin, Cameroon, Ghana, Malawi & Peru,” The Economic Times, 2023, https://www.ris.org.in/sites/default/files/mediacentre/India%20partners%20with%20Germany%20to%20deliver%2C%20Malawi%20%26%20Peru%20-RIS%20in%20Media-Triangular%20Cooperation-2-3%20nov%202023.pdf

[43] Paul Wozniak, “Three Years of UK Aid Cuts: Where Has ODA Been Hit Hardest?” Development Initiatives, 2023, https://devinit.org/resources/three-years-of-uk-aid-cuts-where-has-oda-been-hit-hardest/

[44] UK International Development, “International Development in a Contested World: Ending Extreme Poverty and Tackling Climate Change,” 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6576f37e48d7b7001357ca5b/international-development-in-a-contested-world-ending-extreme-poverty-and-tackling-climate-change.pdf

[45] Government of United Kingdom, Plan of Action to Implement the ASEAN-United Kingdom Dialogue Partnership (2022 to 2026), 2022, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/asean-uk-dialogue-partnership-plan-of-action-2022-to-2026/plan-of-action-to-implement-the-asean-united-kingdom-dialogue-partnership-2022-to-2026

[46] Government of United Kingdom, UK and India Launch New Grids Initiative to Deliver Clean Power to the World, 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-and-india-launch-new-grids-initiative-to-deliver-clean-power-to-the-world

[47] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, UK-India Global Partnership Programme, https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/Tender/5138_2/1_4_Tender-1-1.pdf

[48] Anthea Mulakala, “India’s Approach to Development Cooperation,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Development Cooperation for Achieving the 2030 Agenda, 2019.

[49] Cheryl McEwan and Emma Mawdsley, “Trilateral Development Cooperation: Power and Politics in Emerging Aid Relationships” (paper presented at OUCAN workshop, Oxford, March 2012 and RGS-IBG Annual Conference, July, 2012).

[50] MEA Performance Dashboard

[51] Prime Minister’s Office, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1926143#:~:text=James%20Marape%20received%20Prime%20Minister,with%20the%20Pacific%20Island%20countries

[52] Ministry of External Affairs (speech, FIPIC III Summit, May 22, 2023), https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/36588/English_translation_of_Prime_Ministers_closing_statement_at_the_FIPIC_III_Summit

[53] UNESCO, “Technology in Education: A Case Study on Timor-Leste,” 2023, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000387828

[54] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, China: A Development Partner to the Pacific Region, 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/zwjg_665342/zwbd_665378/202203/t20220311_10650946.html

[55] Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmire, “The Chinese ‘Debt Trap’ is a Myth,” The Atlantic, 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2021/02/china-debt-trap-diplomacy/617953/

[56] “Inflation, Drought Push Djibouti to Suspend Loan Payments to China,” ADF Magazine, 2023, https://adf-magazine.com/2023/01/inflation-drought-push-djibouti-to-suspend-loan-payments-to-china/https://adf-magazine.com/2023/01/inflation-drought-push-djibouti-to-suspend-loan-payments-to-china/

[57] Alex Vines OBE, “Climbing out of the Chinese Debt Trap,” Chatham House, 2022, https://www.chathamhouse.org/publications/the-world-today/2022-08/climbing-out-chinese-debt-trap

[58] Swati Prabhu and Nilanjan Ghosh, “Does “Market Imperialism” Drive China’s Development Partnership Model?” Observer Research Foundation, 2023, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/does-market-imperialism-drive-chinas-development-partnership-model/

[59] United Nations Development Programme, “South-South and Triangular Cooperation in Indonesia,” 2015, https://www.undp.org/indonesia/publications/south-south-and-triangular-cooperation-indonesia

[60] Ministry of National Development Planning, Republic of Indonesia, “Indonesia’s Foreign Policy, Indonesia South-South and Triangular Cooperation,” https://www.cbd.int/financial/southsouth/Indonesia-south.pdf

[61] Nur Masripatin, “Indonesia’s South-South and Triangular Cooperation Experiences in the Context of ASEAN,” UNFCC, 2018, https://unfccc.int/ttclear/misc_/StaticFiles/gnwoerk_static/events_2018_4/081b6401e98e4f539ea5a2df9f2eb424/869985e145df42c687e51941dc937ca7.pdf

[62] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Indonesia, The Bali Message for Development Cooperation in the Pacific, The Indonesia Pacific Forum for Development, 2022, https://kemlu.go.id/portal/en/read/4233/siaran_pers/the-bali-message-for-development-cooperation-in-the-pacific-the-indonesia-pacific-forum-for-development

[63] Chris Alden, Sally Morphet, and Marco Antonio Vieira, “The South in World Politics: An Introduction,” in The South in World Politics (United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 1-23, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230281196_1

[64] Cheryl McEwan and Emma Mawdsley, “Trilateral Development Cooperation: Power and Politics in Emerging Aid Relationships,” Development and Change 43, no. 6 (2012).

[65] McEwan and Mawdsley, “Trilateral Development Cooperation: Power and Politics in Emerging Aid Relationships”

[66] Development Assistance Committee, “Shaping the 21st Century: The Contribution of Development Co-operation,” Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1996, https://www.oecd.org/dac/2508761.pdf

[67] Niels Keijzer and Erik Lundsgaarde, “When ‘Unintended Effects’ Reveal Hidden Intentions: Implications of ‘Mutual Benefit’ Discourses for Evaluating Development Cooperation,” Evaluation and Program Planning 68 (2018): 210-17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.09.003

[68] McEwan and Mawdsley, “Trilateral Development Cooperation: Power and Politics in Emerging Aid Relationships”

[69] McEwan and Mawdsley, “Trilateral Development Cooperation: Power and Politics in Emerging Aid Relationships”

[70] Soyeun Kim, “Korea: ‘Something Old’ and ‘Something Borrowed’,” NORRAG Newsletter 44, (2010): 76-78, https://resources.norrag.org/storage/documents/0R2AWkm6kjMCMKpYFvisiUzYMwueeU6Vy8SofUGo.pdf

[71] McEwan and Mawdsley, “Trilateral Development Cooperation: Power and Politics in Emerging Aid Relationships”

[72] Goran Hyden, “After the Paris Declaration: Taking on the Issue of Power,” Development Policy Review 26 (2008): 259.

[73] “Malaysia, China Agree to Resume Railway Project After Slashing Cost,” Reuters, April 12, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN1RO0LV/

[74] Prithvi Gupta, “Chinese Incursions in the South Pacific,” Observer Research Foundation, 2022, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/chinese-incursions-in-the-south-pacific/

[75] Ben Doherty and Kate Lyons, “Outgoing President of Micronesia Accuses China of Bribery, Threats and Interference,” The Guardian, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/mar/10/outgoing-president-of-micronesia-accuses-china-of-bribery-threats-and-interference

[76] “Sri Lanka Signs Deal on Hambantota Port with China,” BBC, July 29, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-40761732

[77] Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, “Why Indonesia Should Be Cautious in Extending its High-Speed Railway,” The Diplomat, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/07/why-indonesia-should-be-cautious-in-extending-its-high-speed-railway/

[78] Talita Yamashiro Fordelone, “Triangular Co-operation and Aid Effectiveness: Can Triangular Co-operation Make Aid More Effective?” ECD Journal: General Papers 1 (2010), https://doi.org/10.1787/gen_papers-2010-5kgc6cl31rnx

[79] Anthony Kleven, “Belt and Road: Colonialism with Chinese Characteristics,” Lowy Institute, May 6, 2019, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/belt-road-colonialism-chinese-characteristics

[80] Kevin P. Gallagher, Jose Antonio Ocampo, and Ulrich Volz, comment on “IMF Special Drawing Rights: A Key Tool for Attacking a COVID-19 Financial Fallout in Developing Countries,” Brookings, comment posted March 26, 2020, https://brookings.edu/articles/imf-special-drawing-rights-a-key-tool-for-attacking-a-covid-19-financial-fallout-in-developing-countries/

[81] Ministry of External Affairs, India and United Nations, 2020, https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/India_UN_2020.pdf

[82] Harsh Vardhan Shringla, “India’s Foreign Policy in the Post-Covid World: New Vulnerabilities, New Opportunities” (speech, June 18, 2021), Public Affairs Forum of India, Speeches and Statements, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/33929/Foreign_Secretarys_Remarks_on_Indias_Foreign_Policy_in_the_PostCovid_World_New_Vulnerabilities_New_Opportunities_Public_Affairs_Forum_of_India

[83] Terence Wood, Sabit Otor, and Matthew Dornan, “Why are Aid Projects Less Effective in the Pacific?” Development Policy Review, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fdpr.12573

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV