-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Abhishek Mishra and Satyajit Sen, “Maritime Security and Development in the South-West Indian Ocean Region: Harnessing India’s Engagement with Small Island Developing States,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 353, April 2022, Observer Research Foundation.

Image Source: Maritime Security and Development in the South-West Indian Ocean Region: Harnessing India’s Engagement with Small Island Developing States

Introduction

In the post-Cold War era, the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) experienced instability exacerbated by weak government structures and the littorals’ limited capacity in controlling the maritime domain.[1] As security threats increased in form and frequency, the IOR experienced growing militarisation by regional and extra-regional powers.

India has traditionally enjoyed close, multi-faceted bilateral and multilateral ties with these SIDS, which it considers part of its extended maritime neighbourhood. Indian interests in these island nations are guided by security, cultural, and economic factors. As a fellow developing postcolonial nation, India is also cognisant of the unique circumstances and challenges they face in their pursuit of development. As part of its commitment to South-South Cooperation (SSC) and its growing profile as a regional power, India has demonstrated its capabilities and willingness to assist them in dealing with common maritime and developmental challenges—largely in the form of robust trade, investments, and defence partnerships.

Enhancing cooperation and establishing new links with SIDS form a core tenant of India’s foreign policy in the IOR.[4] In 2015, it inaugurated its vision of SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region), in Mauritius.[5] The choice of Mauritius highlights the centrality of the SIDS of the SWIO region to India, and reflects the country’s desire to ensure that they remain part of its regional maritime and strategic consciousness. Furthermore, India has endeavoured to develop and harness their collective maritime competencies to meet and combat common challenges. To be sure, however, India’s challenges may not necessarily be in parallel with those of the SIDS.[6]

The SIDS of the SWIO region vary in area, population size and density, geographical spread, and developmental progress.[7] They all share a vulnerability to natural disasters, climate change, and external economic shocks while lacking economies of scale, diversification opportunities, and a sizeable domestic market. Due to their unique, remote geography, these island states have specific needs that any external power such as India must consider while undertaking any engagement.[8]

Following the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1982, SIDS acquired vast Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of 200 nm, often larger than their landmass. Based on this newfound jurisdiction over vast marine spaces, many SIDS began referring to themselves as “Large Ocean States.”[9] As Pete Hay has argued, “Sea, which is common to most of the islands across the globe creates a distinctive island identity.”[10] This intrinsic relationship between the islands and the surrounding ocean reinforces the island identity of SIDS. Their unique geography—surrounded by sea, their islandness,[a] absence of hinterland and perhaps their insularity and isolation—creates a distinctive sociocultural and political identity amongst islanders. External stakeholders should seek to understand this geographical and political identity of the islands and the islanders,[11] to contextualise the maritime security challenges facing the SIDS of the SWIO region.

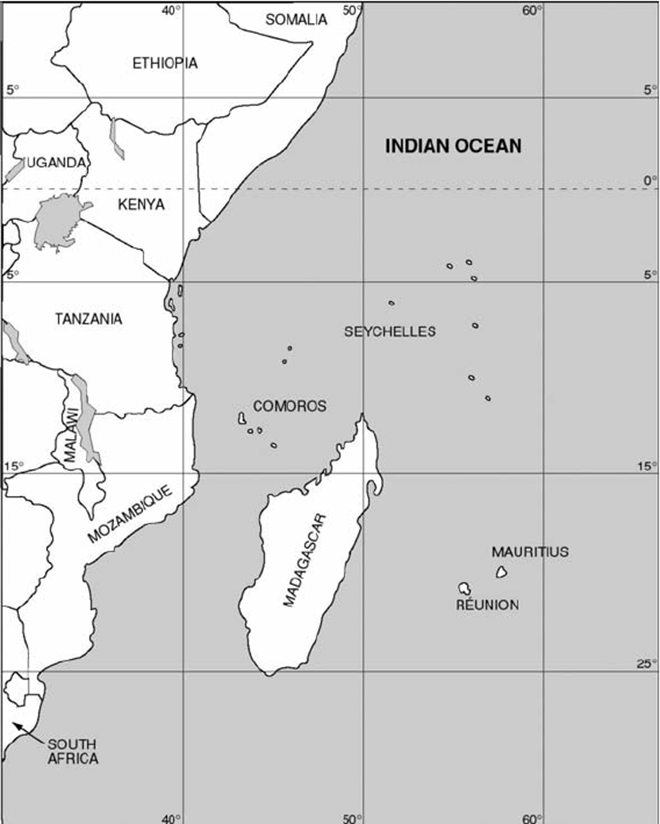

The South-West Indian Ocean: An Overview

The SWIO region can be defined as the nautical area where the African sovereign island states of Mauritius, Seychelles, Comoros, and Madagascar are strategically located—southwest of the IOR, adjoining the eastern/southeastern coastline of the African continent. The strategic significance of the SWIO region is conspicuous, because the region is close to parts of a troubled mainland in East Africa and West Asia. The SWIO region is also connected to the prominent SLOCs and the troubled waters off the coast of Somalia, where international piracy and sea-borne terrorism remain rampant.[12] Thus, the region is critical to the security and stability of the IOR and the 21st century geopolitical imperative, marked by the strategic and economic rise of regional powers such as India and China and the formation of a complex multipolar world. Given the SWIO region’s strategic importance, most rising powers, such as India and China, have a significant stake there, especially in the region’s SIDS.

Figure 1. Map of the South-West Indian Ocean Region

Source: Jeremy Kiszka, et al., 2009

India and China have competing interests in the SWIO region as their IOR maritime rivalry has intensified in recent years.[13] The SLOCs near the SWIO region that pass through the IOR are vital to these two rising powers for trade, energy, and economic security. India’s comprehensive maritime strategy in the region is driven by its aspiration for sea control to counter Beijing’s expanding blue-water naval capabilities in the IOR. Whether under the garb of anti-piracy patrols off the East African coast or deploying its research and fishing vessels and maritime militia, the Chinese Navy has maintained a continuously increasing presence in the IOR. Furthermore, East Africa and the SIDS of the SWIO region have developed into a central node in the Maritime Silk Road (MSR), connected by planned and finished ports, pipelines, railways, and power plants constructed and funded by Chinese companies and lenders.[b] China’s presence in the IOR presents an enormous political and military challenge for India, especially the scale and intensity of Beijing’s diplomatic and political energy in the SWIO region through the MSR and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).[14]

The geopolitical and strategic competition between the two nations makes the SWIO region’s SIDS particularly important as potential allies and strategic partners. Political scientist Eleanor Albert notes, “Competition between Beijing and New Delhi is not necessarily overt, but each country is seeking to strengthen ties with smaller regional states to secure their respective security and economic interests.”[15] For both India and China, losing these SIDS as regional partners will result in the loss of influence in the SWIO region. Ultimately, the competing interests between the two make for a zero-sum game, resulting in the act of balancing each other’s influence.

Other powers such as the US and France have also expressed concerns about China’s growing IOR presence and its massive overtures through the BRI. Until now, the US has been an undisputed resident power in the IOR, and it maintains a significant military presence on the island of Diego Garcia at the centre of the IOR. France is another significant security player in the greater IOR and a traditional hegemon in the SWIO region, having been a colonial power until the last century. France maintains strategic assets in the IOR, particularly in the SWIO region, including the island territories (Scattered Islands); the EEZ along the Mozambique Channel; and a military presence on Mayotte and Reunion, which remain overseas departments of France. France maintains a 2.8 million km square of EEZ in the IOR, contributing to 20 percent of its EEZ globally.[16]

The US’s and France’s activities and role in guiding the evolving maritime security architecture in the SWIO region are relevant to Indian policy and outreach to the SIDS in the region. Based on their shared concern about China’s diplomatic and political attempts to co-opt these SIDS, India has been cooperating with both the US and France to thwart the Chinese influence in the region. India has participated in US initiatives such as the CUTLASS Express, a US-Africa Command-sponsored multinational maritime exercise to promote national and regional maritime security in East Africa and the Western IOR, in which the SIDS of the SWIO region also participate.[c] France’s activities in the SWIO region take into account Indian interests, since both countries have emerged as close maritime security partners in recent years due to their shared vision of a free and open Indian Ocean and Indo-Pacific.[d]

Professor Donald Berlin notes, “India’s rise in the Indian Ocean also will have important implications for the West and China”[17] and that it “will be welcomed by the United States and other ‘Western states’ to the extent that it counteracts the challenge posed by China, the world’s other salient rising power.”[18]

Key Challenges for the SIDS of SWIO

Nearly a quarter of the world’s sovereign nations are islands, which are home to approximately 10 percent of the global population.[19] Islands and their inhabitants, however, remain marginalised amongst the community of nations and receive much less attention than they deserve. Islands scholar Godfrey Baldacchino observes, “Thanks to an apparent yet beguiling openness, it is deceptively simple to conceive ‘the island’ as the convenient platform for any whim or fancy.”[20]

Islands have been sites for military bases and political exiles in history, as well as the subject of utopian and dystopian literature.[21] They have long been an object of manifestation and a subject of colonial imagination. From specific sites for plantation economy to being gizmos for sea command, islands played an imperative role during the age of sail, when European powers were colonising distant lands across the world’s mighty oceans. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the formation of the United Nations and the subsequent fall of many European great powers dealt a heavy blow to colonial and imperial occupations. Independence and sovereignty grew amongst former large and small colonies in distant lands and waters far away from the European continent and mainland. Many of these colonies were islands and archipelagos whose independence led to small states’ large-scale proliferation, especially the SIDS. Although some chose to remain an integral part of their European metropole for economic benefits, many of these former colonial islands decided to chart their own postcolonial socioeconomic and political future despite their size, population and remote geography.

The emerging geopolitical milieu holds challenges and opportunities for the SIDS of the SWIO region. According to International Relations theorist Robert Keohane, “If Lilliputians can tie up Gulliver, or make him do their fighting for them, they must be studied as carefully as the giant.”[22] The significance of these island states is not going to fade away; instead, they are increasingly being placed at the centrestage. It is now up to these island states to decide whether they prefer to remain peripheral actors or play a bigger role in the geopolitical milieu of the IOR.

Norwegian political scientist Iver B. Neumann notes, “Small states and great powers are mutually constitutive – if there were no small states, there could be no great powers. In fact, the great powers have always been a minority in the society of states: the vast majority of states have been and are minor powers.”[23] These island states must remain vigilant and employ smart power strategies, i.e., a combination of hard and soft power elements. According to American scholar Ernest J. Wilson, “Achieving smart power requires artfully combining conceptual, institutional, and political elements into reform movement capable of sustaining foreign policy innovations into the future.”[24] Given the geopolitical and strategic considerations of the SWIO region, these SIDS must build up and capitalise on such smart power.

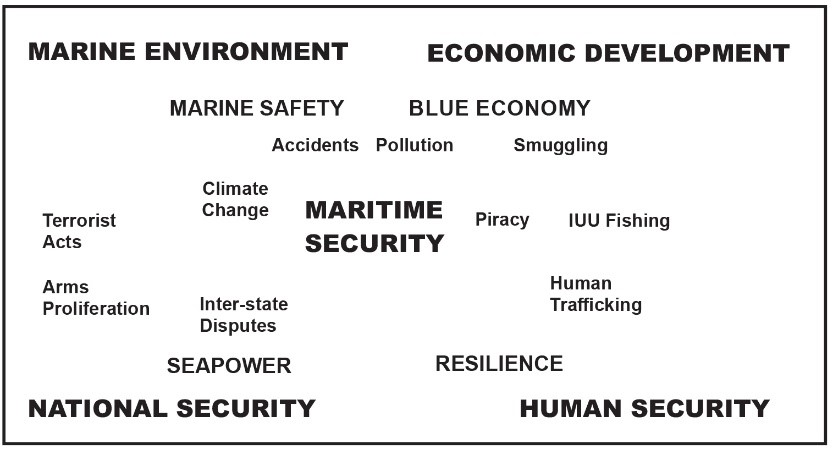

Figure 2. Christian Bueger’s Maritime Security Matrix[f]

Source: Christian Bueger, 2015.

Marine Environment Protection, Climate Change, Blue Economy, Piracy, and Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated fishing (IUU Fishing) are critical transnational security and development issues concerning the SIDS of the SWIO region. These issues are also the key drivers in their engagement with major regional and extra-regional powers. However, epistemologically, the perspectives of these SIDS towards maritime security and development significantly differ from those of regional and extra-regional powers.[28] The main concerns of the SIDS are issues that affect them directly, rather than the geopolitical and strategic competition amongst major powers in the region. Nevertheless, cognisant of the geopolitical realities, the SIDS are navigating to balance the competing strategic interests of major powers with the security interest of the region, promoting a holistic understanding of the region’s maritime security needs.

The bilateral and multilateral security engagements between global powers and SIDS reflect the importance of SIDS in regional maritime security construct. However, for the African SIDS of the region, achieving maritime security has been a significant challenge. The major powers must understand that threats to maritime security are primarily non-traditional and transnational.[g] The African SIDS, for their part, should reinforce and promote maritime security and development in their security cooperation with major powers, with a focus on holistic maritime security: inter-relational concepts of national security, marine environment, economic development, and human security.

The Centrality of SIDS in India-Africa Engagement

India enjoys a South-South Cooperation (SSC) tradition with fellow developing countries, Least Developed Countries (LDCs), and SIDS. As a developing country with a long coastline of over 7,500 kilometres and several groups of islands located away from its mainland peninsula, India understands the challenges to achieving sustainable development on small islands. Various structural deficiencies affect the SIDS due to their remoteness and lack of connectivity, limited land resources, small population, economies of scale, the stark threat of climate change and sea-level rise, lack of diversification, high transport costs, and vulnerability to external shocks—placing SIDS at a relative disadvantage.[29] The energy and food crises, compounded by the challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, have exacerbated these vulnerabilities. Amidst these obstacles, India has stood unwaveringly with its Indian Ocean SIDS neighbours as they pursue their developmental goals, despite its own limited resources and fiscal and capacity constraints. Furthermore, driven by its “share and care” approach to development and its commitment to the Global South, India has shared with them its developmental experience, expertise, and technological resources.

Much of India’s increasing developmental assistance to the SIDS of the SWIO region is aligned with the country’s attempts at developing a clear and long-term vision for engagement with the African continent. Since Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration took charge in 2014, India’s diplomatic outreach and political engagement with Africa have been sustained and regular.[30] India and Africa have been working together to improve their SSC partnership by formulating joint solutions to common challenges in areas such as clean technology, climate-resilient agriculture, maritime security, connectivity, and blue economy. PM Modi’s articulation of the “Ten Guiding Principles for India-Africa Engagement,” also known as the “Kampala Principles,” during his address to the Ugandan Parliament in July 2018 reflected a change in the nuances and priorities of India’s engagement with Africa.[31]

New initiatives, such as the Africa-India Field Training Exercise (AF-INDEX) in March 2019, the e-VidyaBharati and e-ArogyaBharati (e-VBAB) project, and the inaugural India Africa Defence Ministers Conclave (IADMC) out of which the “Lucknow Declaration” was adopted in February 2020,[32] have added new momentum to India-Africa ties. Furthermore, India is Africa’s third-largest trading partner, with the total trade growing from US$6.8 billion in 2003 to US$76.9 billion in 2018,[33] and the fifth-largest investor in the African continent, with cumulative investments from April 1996 to March 2019 amounting to US$64.6 billion.[34] Out of the overall US$10 billion Lines of Credit (LOC) that India committed to at the third India-Africa Forum Summit (IAFS) in 2015, India has already disbursed US$6.4 billion to various African countries. Additionally, India had committed over US$700 million as grant assistance—US$100 million in addition to the US$600 million that was promised during IAFS-III.[35],[h]

An important example of India’s partnership with SIDS was evident during the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), when PM Modi launched the Initiative for the Resilient Island States (IRIS) to develop small islands’ infrastructure.[36] This initiative is part of the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI),[i] which focuses on building capacity for SIDS. Furthermore, since climate change threatens the very existence of these island nations, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) is working on developing a special data window to provide the SIDS with timely information on cyclones, coral-reef monitoring, and coastline monitoring through satellites.

India’s focus on development partnership and growing two-way trade and investments continue to drive its engagement with the SIDS of the SWIO region. However, in recent years, maritime safety and security cooperation has emerged as a key subset of this engagement,[37] due to the recent increase in non-traditional threats and blue crimes in these island states. Thus, the “Vanilla Islands”[j] have emerged as a critical engagement area between India and Africa, as they increasingly turn towards India to achieve sustained national growth and development.[38] In turn, the SWIO region’s abundant and rich natural resource profile has furthered India’s interests in these nations.

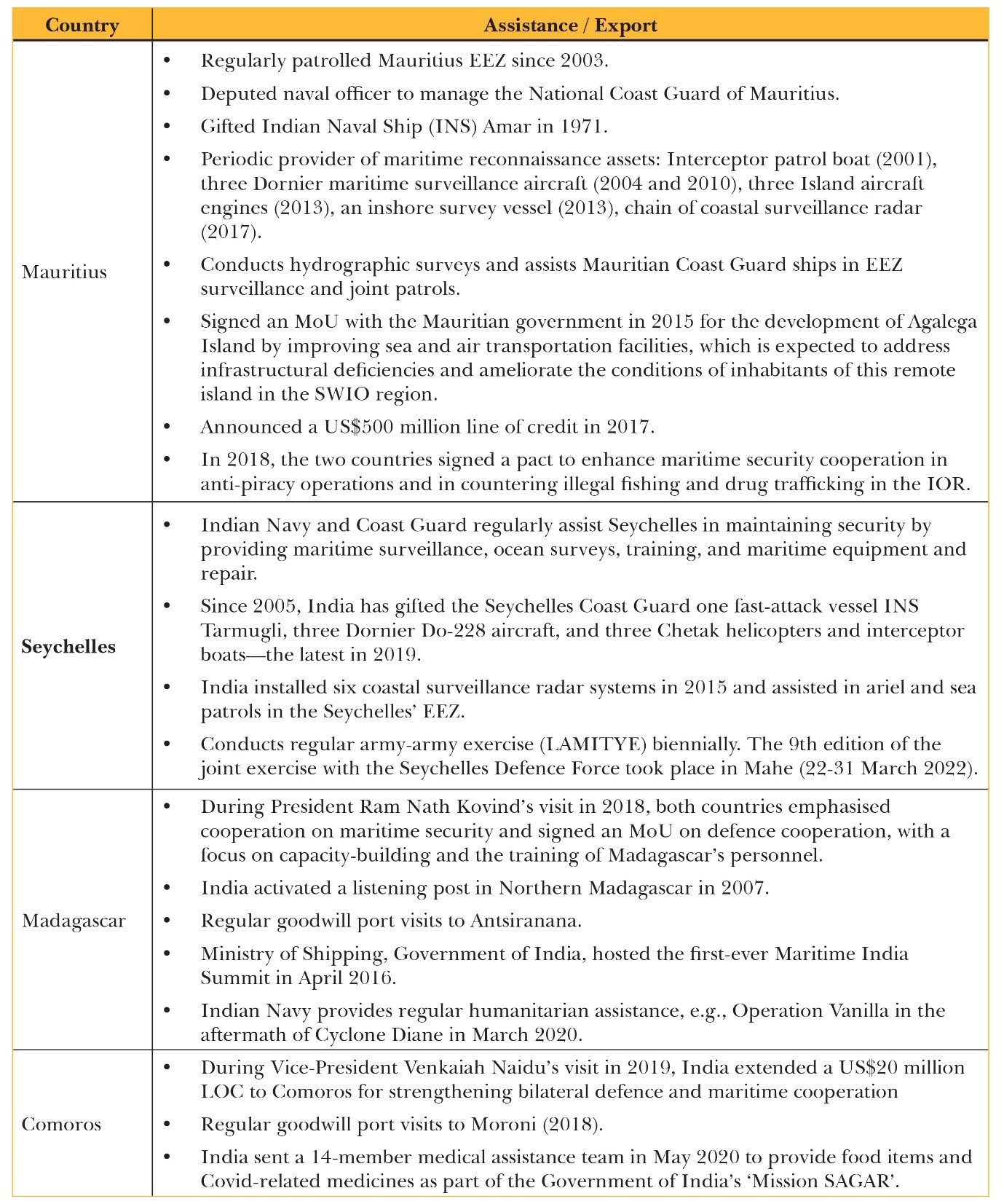

The following table shows India’s maritime assistance to the SIDS of the SWIO region over the years.

Table 1: India’s Maritime Assistance to the SIDS of the SWIO Region

Source: Premesha Saha and Abhishek Mishra, Observer Research Foundation, December 2020.

India has been a steady and vocal proponent of increased participation of African littorals and SIDS in various multilateral frameworks in the IOR. East and Southern African countries that share a coastline along the Indian Ocean and the SIDS of the SWIO region have tremendous potential to work with India in advancing their maritime security interests and advocating for the sustainable use of marine resources. While most instances of engagement between India and the region’s littorals have been bilateral thus far, there has been growing multilateral engagement through regional and subregional organisations in recent years.

Currently, all SIDS in the region require assistance in developing their maritime domain awareness,[43] since it is not possible for them to patrol their large EEZs without effective capacity. This creates a window of opportunity for India, with its demonstrated capability to assist its neighbouring SIDS partners, to play a more influential role in developing the maritime security architecture in the SWIO region. For example, the Regional Maritime Information Fusion Centre (RMIFC) based in Madagascar and the Regional Coordination Operations Centre (RCOC) based in Seychelles can benefit greatly from linking these centres with India’s Information Fusion Centre-Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR) located in Gurugram, India.

China’s Engagement with SIDS: Implications for India

India’s outreach to the SIDS of the SWIO region cannot be understood without considering China’s MRS-BRI. These SIDS have generally maintained economic links with India and China without being overly dependent on either. Instead, they have demonstrated agency in their interactions with both the rising powers, who continue to engage in a geostrategic competition for influence in the IOR and the SWIO region.

For India, the SIDS have historically been part of the extended maritime neighbourhood, and its ties with these nations are guided by security, cultural, and economic reasons. China, for its part, is driven largely by economic considerations. China’s dependence on overseas energy supplies, especially oil and natural gas, has been key in shaping its strategy and engagement in the IOR.[44] At the same time, the African SIDS of the SWIO region, too, are expanding trade and investment links with China to develop their economies. In terms of development partnership, India has distinguished itself from China by insisting that India’s approach towards development is human-centric and that its partnerships are marked by respect, diversity, future prospects, and sustainable development.[45] India maintains that, unlike China’s engagement, its development aid model is completely non-conditional and is not influenced by either political or commercial considerations.

At the same time, China positions itself as a rule- and norm-setter for global development practices of the future.[46] The country has released three white papers defining its approach to foreign assistance: in 2011, 2014, and 2021.[47] Chinese development assistance insists on the principles of mutual learning, sustainability, lasting impact, and breaking new ground. However, various industrial economies have criticised the BRI for lacking transparency, its ad-hoc nature, its tendency to push developing economies into a “debt trap,” and allegations of corruption and unfair labour practices.[48]

Both India and China view the SWIO region’s SIDS as destinations for setting up manufacturing bases to export their goods into continental Africa. Through a strategy of balancing and bandwagoning, SIDS such as the Seychelles and Mauritius have exerted their agency and ability to influence events, especially ones that concern their own security.[49] In the future, India and China will continue to position themselves as these island nations’ principal development partner, likely through economic support such as investments, and lines of credit. Further, both nations will continue to finance the construction of high-impact community development projects in line with the national priorities of these SIDS.

Mutual Avenues of Maritime Cooperation under the IOC

In March 2020, India, with the assistance of France, was inducted as an observer to the IOC.[50] This development is expected to facilitate India’s collective engagement with the SWIO region’s SIDS. As Professor Kate Sullivan de Estrada notes, “With its observer status, India will be called upon to extend its expertise in the region, put its satellite imagery to the service of the RMIFC, and establish links with its own Information Fusion Centre.”[51] Already, Seychelles has posted its first International Liaison Officer at India’s Information Fusion Centre. It is hoped that other SIDS of the SWIO region will follow suit.

According to Satyajit Sen, “The multilateral IOC shall remain pivotal in shaping the engagement of the SIDS of the SWIO region with the major powers in the era of the Indo-Pacific. Multilateral security will be a positive endeavour for these countries. With increased capabilities, the SIDS—acting under a multilateral institution and with a common voice—should engage with the major powers to secure their backyard and set their agenda on their terms as the geopolitical reality unfold.”[52] India and the SIDS of the SWIO region can promote their mutual maritime security and development interests through the IOC. Maritime Safety and Security, Maritime Domain Awareness, and tackling maritime terrorism and illicit crimes are crucial aspects of India’s engagement with the IOC, and India has adequate experience and expertise in all these aspects. Better coordination and cooperation with the IOC can enhance maritime collaboration with members and observers, resulting in a safe, secure, and prosperous SWIO region.

Cooperation in maritime security and blue economy with the SIDS of the SWIO region is vital for India, and beneficial for all parties involved. Blue economy, in particular, holds immense potential for both India, SIDS, and East African littorals, with the African Union (AU) declaring it the “new frontline of African renaissance.”[53] Similarly, both the AU’s Agenda 2063 and the 2050 Africa Integrated Maritime Strategy (AIMS 2050) emphasise the development of blue economy to drive the African continent’s growth and sustainable development. During his address at the International Fleet Review in Vishakhapatnam in February 2016, PM Modi called the oceans “the lifelines of global prosperity,”[54] and said the Blue Chakra in the Indian national flag represented the potential of blue economy. Subsequently, in the 2015 Delhi Declaration, both India and Africa reiterated their desire to collaborate more closely on this sector.[55] The African SIDS of the SWIO region are the main proponents of this concept, since the populations of these islands are heavily dependent on the oceans for livelihoods and sustenance.

With India’s inclusion as an observer to the IOC, it now has an opportunity to engage with the SIDS in a holistic manner. Through this engagement, India must address the needs of the SIDS to ensure maritime security and development on their terms, which can be aligned with India’s needs and aspirations to play a greater role in steering the waters of the SWIO towards a more stable, secure, and sustainable future.

Conclusion

The small island developing states of the South-West Indian Ocean region are becoming vital security, economic, and developmental partners for India amidst the emerging geopolitical milieu in the IOR. As India reimagines its neighbourhood along its Neighbourhood First Policy and the SAGAR vision, the country is making sure that its maritime neighbours, including the island states of IOR, no longer remain peripheral to the region’s maritime security and development paradigm. While most of India’s engagements with these island states so far have been bilateral, multilateral engagement is gaining traction. This presents India with an excellent opportunity to distinguish itself from China and play a more constructive role in the SWIO region.

Engaging bilaterally and multilaterally with these SIDS will help India facilitate stronger partnerships to address the challenges of maritime security and development in the region. However, to avoid falling into old patterns of western hegemony in the Global South, India must be cognisant of the perspective of the island states while undertaking its engagements. It is imperative for India’s commitment to supporting the SIDS of the SWIO region to be guided by a symbiosis of the island worldview and India’s own interests.

Endnotes

[a] Philip Conkling defined “islandness” as a “metaphysical sensation that derives from the heightened experience that accompanies physical isolation.” He argued that “islandness” is a sense that is absorbed by islanders through the obstinate and tenacious hold of the island community.

[b] According to a Centre for Strategic & International Studies report in 2019, there are at least 46 existing or planned port projects in sub-Saharan Africa, which are funded, built and or operated by Chinese entities. All these ports are strategically positioned along each of Africa’s coasts. This provides China with access to main maritime routes and chokepoints. Two of the most vital developments in this respect have been in Kenya and Tanzania, which are both part of the SWIO. In June 2021, China finished the construction of Lamu port in northern Kenya, which is touted to be Kenya’s second deep-water port, and reports from Tanzania suggest that its President Samiha Suluhu Hassan has decided to revive talks with China to revive the US$10 billion previously-cancelled Bagamoyo port project. While the exact nature of these ports may not be overtly military, they do serve as hubs to project Chinese maritime power in the WIO and broader IOR.

[d] In 2018, the two nations unveiled a joint strategic vision for India-France bilateral cooperation in the IOR. For more, see.

[e] In March 2008, the Comorian forces, backed by the African Union forces, including troops from Sudan, Senegal, Tanzania, and logistical support from Libya and France, led an amphibious assault to topple the leadership of Colonel Mohamed Bacar, who was the President of Anjouan from 2001-2008. The assault came after Colonel Bacar refused to step down after a disputed election, which stood in defiance of the federal government and the African Union. See.

[f] Professor Christian Bueger in his article “What is maritime security?” (2015) attempts to understand maritime security by recognising maritime security with four other concepts: seapower, marine safety, blue economy, and human resilience. Each of these concepts points us to the different dimensions of maritime security. The maritime security matrix places maritime security at the centre of these issues and attempts to understand their relationship with one another. It is important to note that while for some actors, certain issues might be linked primarily to the economic dimensions. In contrast, it is, for others, an issue of national security and safety.

[g] Speaking on the occasion of the 41st Summit of SADC Heads of State and Government on 17 August 2021, Seychelles President Wavel Ramkalawan reiterated the importance of maritime security as a prominent feature of the Seychelles security agenda. He noted that despite the Western Indian Ocean accounting for 12 percent of the global world trade, there has been a proliferation of illicit drugs and weapons, and trafficking of persons transported via these maritime routes, which undermine the regional and internal security of East African SIDS. As a result, even if maritime security might seem to be a somewhat distant concept to people on the mainland, SIDS take cognisance of the need to ensure the protection of its waters. For more, see.

[h] While the fourth iteration of the IAFS, scheduled to take place in 2020, has been delayed due to the pandemic, it is likely to be scheduled sometime in 2022.

[i] The Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI) is a multi-stakeholder global partnership of national governments, UN agencies, multilateral development banks, financing mechanisms, knowledge institutions and the private sector. It aims to promote the resilience of existing and new infrastructure systems to climate and disaster risks in support of sustainable development. The initiative was launched by PM Modi during his speech at the UN Climate Action Summit in September 2019. As of March 2022, the CDRI consists of 29 national governments and seven regional organisations. For more, see.

[j] Vanilla Islands is an affiliation of the islands of Seychelles, Mauritius, Madagascar, Reunion (France), Comoros, and Mayotte (France) in the Indian Ocean as a travel destination brand. In 2010, they came together to pool its forces and market the region as a combined tourism destination.

[k] The Priority and Focus Areas of IORA are: Maritime Safety & Security; Trade & Investment Facilitation; Fisheries Management; Disaster Risk Management; Tourism & Cultural Exchanges; Academic, Science & Technology; Blue Economy; and Women’s Economic Empowerment

[l] The Secretary General of the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) Prof. Velayoudom Marimoutou, in an interview that featured in IOC’s 2020 Annual Report, underscored why maritime security is a “prerequisite” for all the SIDS of the SWIO region. He stated that with external assistance from the EU and countries such as India, the SIDS are working on setting up a collective maritime surveillance, monitoring and response architecture for the Western Indian Ocean. He acknowledged that the sinking of the Wakashio ship demonstrated the imperative to strengthen this mechanism, and to further engage national authorities in information exchange, risk prevention, and joint interventions. For more, see.

[1] Thean Potgieter, “Maritime security in the Indian Ocean: strategic setting and features,” Institute for Security Studies, Paper No. 236, August 2012.

[2] Darshana M. Baruah, “The Small Islands Holding the Key to the Indian Ocean,” The Diplomat, February 24, 2015.

[3] James Jay Carafano, “Why Small States Matter to Big Powers,” The Heritage Foundation, August 13, 2018.

[4] Bidanda Chengappa, “India’s island diplomacy gains momentum,” The Hindu Business Line, December 22, 2020.

[5] “Text of the PM’s remarks on the Commissioning of Coast Guard Ship Barracuda,” PMIndia.gov.in, March 12, 2015, https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/news_updates/text-of-the-pms-remarks-on-the-commissioning-of-coast-ship-barracuda/

[6] Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, “The Trouble with India’s Indian Ocean Diplomacy,” The Diplomat, June 26, 2018.

[7] Fernando Cantu-Bazaldua, “Remote but well connected? Neighbouring but isolated? Measuring remoteness in the context of SIDS,” United Nations Conference for Trade and Development, UNCTAD Research Paper No. 67, May 2021.

[8] Sian Herbert, “Development characteristics of Small Island Developing States,” K4D Helpdesk Report, Institute of Development Studies, 2019, Brighton, UK.

[9] Leila Mead, “Small Islands, Large Oceans: Voices on the Frontlines of Climate Change,” International Institute for Sustainable Development, March 29, 2021.

[10] Pete Hay, “What the Sea Portends: A Reconsideration of Contested Island Tropes,” Island Studies Journal, 8, no. 2 (2013): 209-32.

[11] Godfrey Baldacchino, “Islands, island studies, island studies journal,” Island Studies Journal, 1, no. 1 (2006): 3-18.

[12] Eleanor Albert, “Competition in the Indian Ocean,” Council on Foreign Relations, May 19, 2016.

[13] Derek McDougall and Pradeep Taneja, “Sino-Indian competition in the Indian Ocean island countries: The scope for small state agency,” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 16 (2), December 2020.

[14] Vidhan Pathak, “China and Francophone Western Indian Ocean Region: Implications for Indian Interests,” Journal of Defence Studies, 3, no. 4 (October 2009).

[15] Eleanor Albert, “Competition in the Indian Ocean.”

[16] Agathe Maupin, “France in the Indian Ocean: A Geopolitical Perspective and its Implications for Africa,” South Africa Institute of International Affairs, Policy Insights No. 42, 2017.

[17] Donald L. Berlin, “India in the Indian Ocean,” Naval War College Review, 59, no 2, article 6 (2002).

[18] Donald L. Berlin, “India in the Indian Ocean.”

[19] Godfrey Baldacchino, “Islands, island studies, island studies journal.”

[20] Godfrey Baldacchino, “Islands, island studies, island studies journal.”

[21] Godfrey Baldacchino, “Islands, island studies, island studies journal.”

[22] Robert Keohane, “Lilliputian’s Dilemma: Small States in International Politics,” International Organisation, 23(2), 291-310.

[23] Iver B. Neumann, Lilliputians in Gulliver’s World? Small States in International Relations, Centre for Small State Studies, University of Iceland, 2004.

[24] Ernest J. Wilson III, “Hard power, soft power, smart power,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Public Diplomacy in a Changing World, 616, no. 1 (March 2008): 110-124

[25] Christopher Browning, “Small, smart and salient? Rethinking identity in the small states literature,” Cambridge review of international affairs, 19, no. 4 (2006): 669-84.

[26] Jacqueline Braveboy-Wagner, “Opportunities and limitations of the exercise of foreign policy power by a very small state: the case of Trinidad and Tobago,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs, September 2010, 23, no. 3 (September 2010): 407-27.

[27] Chrysantus Ayangafac, “Situation Critical: The Anjouan Political Crisis,” Africa Portal, March 5, 2008.

[28] Anthony Bergin, David Brewster and Aakriti Bacchawat, “Islands and Maritime Security,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute report, 2019.

[29] Ministry of External Affairs, September 3, 2014, https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/23971/Statement+by+High+Commissioner+of+India+to+Fiji+and+Leader+of+Indian+Delegation+at+the+3rd+United+Nations+Conference+on+Small+Island+Developing+States+in+Apia+Samoa+September+03+2014

[30] “Prime Minister’s address at Parliament of Uganda during his State Visit to Uganda,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, July 25, 2018.

[31] HHS Viswanathan and Abhishek Mishra, “The ten guiding Principles for India-Africa engagement: Finding coherence in India’s Africa policy,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 200, July 2019, Observer Research Foundation.

[32] “Lucknow Declaration: 1st India-Africa Defence Ministers Conclave 2020, Lucknow,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, February 6, 2020.

[33] Malancha Chakrabarty, “India-Africa relations: Partnership, COVID-19 setback and the way forward,” Observer Research Foundation, April 26, 2021.

[34] Export Import Bank of India, “AfCFTA: Opportunities for India in Africa’s Economic Integration,” Occasional Paper No.197, March 2020.

[35] “Joint Press Statement by India and the African Union on the Mid-Term Review Meeting of the Strategic Cooperation Framework of the India-Africa Forum Summit III,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 12 September, 2019.

[36] Urmi Goswami, “India reaches out to Island States at COP26,” The Economic Times, November 3, 2022.

[37] Commodore Anil Jai Singh, “India’s maritime engagement with Africa set to grow,” Financial Express, June 17, 2021.

[38] C. Raja Mohan, “Delhi might want to add another geography for its diplomatic lexicon – the Vanilla Islands,” The Indian Express, October 8, 2019.

[39] Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, “Colombo Security Conclave: A New Minilateral for the Indian Ocean?” The Diplomat, August 19, 2021.

[40] “Joint Press Statement of the 5th NSA Level Meeting of the Colombo Security Conclave held on 09 – 10 March 2022, in Maldives,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 10 March, 2022.

[41] John M. Ostheimer, “The Politics of the Western Indian Ocean Islands” (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1975).

[42] Lisa Otto, “Why regional efforts are key to Africa’s maritime security,” The Conversation, January 16, 2018.

[43] Christian Bueger, “Effective maritime domain awareness in the Western Indian Ocean,” Institute for Security Studies, Policy Brief. 2017, 10 pp.

[44] Joshua T. White, “China’s Indian Ocean Ambitions: Investment, Influence, and Military Advantage,” Brookings, Global China, June 2020.

[45] “India’s development aid comes without conditions, says PM Modi,” Hindustan Times, July 30, 2020.

[46] Kristen A. Cordell, “Chinese Development Assistance: A New Approach or More of the Same?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 23, 2021.

[47] “China’s International Development Cooperation in the New Era,” China Daily Global, January 11, 2021.

[48] Tanner Greer, “One Belt, One Road, One Big Mistake,” Foreign Policy, December 6, 2018.

[49] Christian Bueger and Anders Wivel, “How do small states maximize influence? Creole diplomacy and the smart state foreign policy of the Seychelles,” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 14, no. 2 (2018):170-88.

[50] “India Approved as Observer of Indian Ocean Commission,” The Wire, March 6, 2020.

[51] Kate Sullivan de Estrada, “Putting the SAGAR vision to test,” The Hindu, April 22, 2020.

[52] S.S. Sen, “Multilateralism, Security and Development: Indian Ocean Commission in the Indo-Pacific Era,” in Reflections on the Indo-Pacific: Perspectives from Africa.

[53] Johan Spamer, “Blue Economy: A New Frontier of African Renaissance?” The Institute for Security Studies Blog on Global Development and Social Justice, November 13, 2018.

[54] “SAGAR stands for Security and Growth for ALL in the Region: PM Modi at International Fleet Week in Vishakhapatnam,” February 7, 2016.

[55] “Delhi Declaration 2015 – Partners in Progress: Towards a Dynamic and Transformative Development Agenda” October 29, 2015.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Abhishek Mishra is an Associate Fellow with the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis (MP-IDSA). His research focuses on India and China’s engagement ...

Read More +

Satyajit Sen is a policy adviser at the Federation of Prince Edward Island Municipalities Canada and a researcher on islands oceans environment and local governance. ...

Read More +