-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The financial gap that emerging markets have to bridge is huge; between $1 trillion and 1.5 trillion annually is needed for investment in infrastructure.

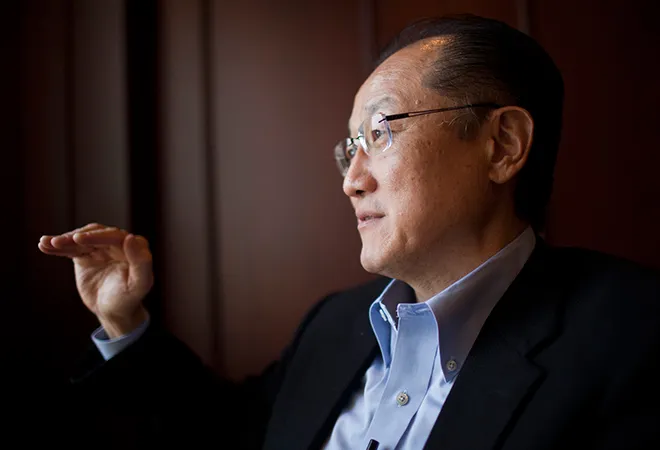

For the head of the World Bank Group to quit unexpectedly would have been big news under any circumstances. But, the reason outgoing president Jim Yong Kim gave for his resignation last Monday is even more revealing. Kim said he was leaving the world’s most influential development and infrastructure-building agency to join a private-sector infrastructure investment fund because he believed “this is the path through which I will be able to make the largest impact on major global issues like climate change and the infrastructure deficit in emerging markets.” One can hardly imagine a more potent indictment of the World Bank’s role in the developing world than having its head vote with his feet.

The truth is that Kim isn’t wrong. The World Bank has simply not been effective enough at what is supposed to be its core task: mobilising funds for infrastructure investment in poorer countries. The financial gap that emerging markets have to bridge is huge; between $1 trillion and 1.5 trillion annually is needed for investment in infrastructure. And how much can multilateral development banks raise in total? All of them put together — not just the World Bank but also regional MDBs such as the Asian Development Bank — can spend about $116 billion a year, according to the Center for Global Development’s Nancy Lee. Worse, only about $45 billion of that goes into infrastructure investment.

Now, one response to this problem could be to capitalise these banks better. But, as we’re likely to discover in the battle between the Trump administration and the rest of the world that is now inevitable after Kim’s resignation, the US isn’t terribly interested in multilateral institutions such as the World Bank. (This is a striking contrast to China, which is looking to scale up the institutions it dominates, such as the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank.) So, more money for the World Bank is out — and even if it was committed, it wouldn’t come close to addressing the “infrastructure deficit” that Kim talks about.

So where will the rest of the money have to come from? Well, from our pockets, that’s where. It’s savers across the world whose money will need to be agglomerated and sent overseas to where it can best be put to work — in the developing world. In other words, private finance will have to step in and put just a fraction of the $90-plus trillion of rich-country savings into emerging-market infrastructure.

This is where the World Bank has fallen short. Back when it was set up, in the 1940s, the bank was supposed to work closely with the private sector, not to make grants or loans of its own money. It was meant, in fact, to be an underwriter of sorts.

Henry Morgenthau, the US treasury secretary back when the Bretton Woods institutions were being designed, was pretty clear about what the bank’s role: “The primary aim of such an agency should be to encourage private capital to go abroad for productive investment by sharing the risks of private investors in large ventures ... The most important of the Bank’s operations will be to guarantee loans in order that investors may have a reasonable assurance of safety in placing their funds abroad." But, as pointed out by Chris Humphrey and Annalisa Prizzon of the Overseas Development Institute, that isn’t how things panned out. In fact, in 2013, less than two percent of the total funds mobilised by all development finance institutions took the form of loan guarantees.

Instead of working with the private sector, the World Bank has become a slack, bloated, public-sector bureaucracy that survives by flattering its host governments and playing it safe with donors. Most of its lending is direct to governments. That is great for all concerned: The bank’s staff just have to monitor the lending process; most need minimal specialist skills. Donor governments can maneuver to use the bank as a tool of their foreign policy. And recipient governments control where the cash goes — frequently into their own state-controlled companies or institutions. Nobody needs to work very hard as long as everyone gets along, which is why the bank goes out of its way not to confront, for example, major “customers” such as the Indian government.

There have been efforts to change this lazy equilibrium in recent years. Since early in Kim’s term, the World Bank and other multilateral development agencies have attempted to de-prioritise concessional loans as an instrument and raise the profile of guarantees. Kim’s premature departure, though, tells us all we need to know about how successful that effort has been.

This commentary originally appeared on Bloomberg.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Mihir Swarup Sharma is the Director Centre for Economy and Growth Programme at the Observer Research Foundation. He was trained as an economist and political scientist ...

Read More +