-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Attribution: Alexis Crow, “Is India the Next ‘Bright Spot’ for Global Investors?,” ORF Special Report No. 204, January 2023, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

Amidst a somewhat unprecedented amount of turmoil in the global macroeconomic environment and geopolitical landscape—from the return of interstate war in Europe and the associated energy and cost of living crises unfurling across advanced and emerging market economies, to the ensuing tensions between the US and China and a deepening of the technological decoupling between the two countries—India has emerged as the next “bright spot”[1] for global investors. Indeed, the World Bank has recently highlighted that India is better positioned to “weather global spillovers”, relative to most other emerging markets.[2]

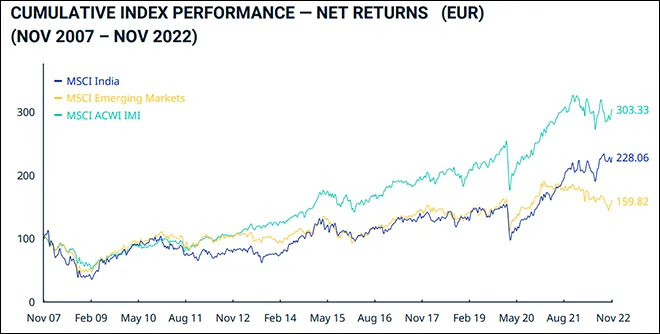

As India retains its position as one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, local benchmarks have hit historic highs. As we can see in Figure 1, on an emerging market basis, Indian stock markets have outperformed their MSCI peers, and rank among the best performing equity markets on a global basis in 2022.[3]

Figure 1: MSCI India vs MSCI Emerging Markets: Cumulative Index Performance – Net Returns (in EUR; November 2007-November 2022)

Foreign investors have played a role in propelling such market rallies, posting steady inflows into Indian equities.[5] In part, investors have responded positively to India’s position as the potential next great growth miracle, as the economy steadily emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic, with a relatively resilient and robust domestic consumer base.[a],[6]

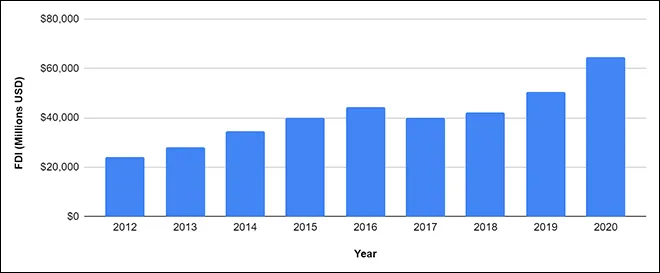

Beyond the compelling macroeconomic story, India’s geostrategic position is also an alluring draw for global pools of capital—and indeed for ‘sticky’ capital, in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI). As we can see in Figure 2, FDI into India has steadily risen in recent years, partly in response to the escalation of the US-China trade tensions in 2018, and likely also increasingly as a factor of the ‘China offset’: amidst the sustained zero COVID policies, some foreign investors and executives have diverted capital allocation from mainland China to India, amongst other emerging market and developing economies and Asian economies.

Figure 2: Foreign Direct Investment into India in value terms (2005-2020)

And yet, one should ask, is India benefiting from what might be described as a chiaroscuro moment, and thus only temporarily touted as a ‘bright spot’ because the current global horizon is otherwise so dark? In short, just how durable is this geographical investing theme of deploying long-term capital to India?

As we shall see, India is not without its own challenges—at the macroeconomic and financial level, and indeed within the geopolitical landscape. Nevertheless, despite both short- and medium-term headwinds, India’s shining star investment status is veritably merited. ‘The next China’, it is not. But as India continues the manufacturing miracle and boosts competitive services exports, it generates the growth for a consumer market that is only at the cusp of blossoming.[b],[8] And, in considering which sectors are likely ripe for capital allocation, the very sectors subject to reforms—including energy, transport, and agriculture technology (AgTech)—provide stellar opportunities for long-term patient capital in private equity, infrastructure, and venture capital. Additionally, both traditional and non-traditional forms of finance continue to provide alluring sectors for allocation amongst foreign investors. Finally, as we shall see, in considering which countries ‘get it right’ by investing in India, Japan provides an excellent role model for other countries as they seek to strategically engage in India.

Macro Snapshot

Despite the extraordinary twin health and economic crises stemming from COVID-19, India actually posted record GDP growth emerging from the pandemic.[9] Policymakers in the Reserve Bank of India were also successful in maintaining smoothly running financial markets during the waves of the virus and associated economic stops, taking measures to provide liquidity to mutual funds, as well as to provide sufficient US dollar liquidity across markets.[10]

More recently, in considering the external outlook, central bankers in India have had to contend with the impacts of ‘geopolitical spillovers into monetary policy’.[11] In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, policymakers have had to contend with imported inflation, resulting both from an elevated commodity price environment and from a depreciating Indian rupee vis-a-vis a strong greenback performance in the wake of US Federal Reserve (Fed) tightening (which is further strengthened from a crowding in to the US dollar as a safe haven asset during such a period of heightened volatility and uncertainty). This current imbalance is likely to moderate in 2023, as it seems that the Fed and central bankers in other advanced economies might have successfully managed to restore price stability, and so to achieve a moderately ‘soft landing’, potentially averting a deep or prolonged recession.

Looking out over the longer-term, India is forecasted to become the world’s third-largest economy by 2030, surpassing both Germany and Japan.[12] Indian GDP is set to double within the next nine years.[13] And, even in the wake of the sudden stops of COVID-19, the Indian middle class is expected to grow by 8.5 percent per year through to 2030, at which time it is forecasted to reach 800 million people.[14] Looking out to the start of the next century, India is set to hold the world’s largest foreign net foreign asset position,[c] again, effectively replacing the positions of Germany and Japan.

In achieving such positions, trials do remain. One such challenge emanates from India’s status as a “democratic cacophony”[15]: as the country’s citizens speak 121 languages and 270 mother tongues, within 28 states and eight union territories, a sense of political cohesion may be somewhat absent amidst these “million negotiations of democracy.”[16] Thus, in considering the prospects for the further implementation of pro-business reforms,[d] as well as for the potential for India to create “public facilities to support private individuals,”[17] India’s democratic polity must be taken into account. To work through the next generation of reforms to land, labour, and intellectual property, a national consensus is required that may not be entirely visible at this point. One big question for the medium term is how such consensus-building might be achieved in order to pave a firm foundation for the development of opportunities for domestic entrepreneurs.

India’s Geostrategic Position: the China Offset, and Implications of Increased Prosperity

Looking out to the regional level—and in considering India within the context of other emerging market peers, or together with other Asian economies—the relatively autonomous position of the country—independent as it is from China—renders it alluring to foreign investors and executives increasingly contending with geopolitical risks between the US and China. Within the context of our current geopolitical landscape—one characterised by fragmentation, rather than that dominated by one hegemon in the form of the US, or two powers, such as the US and China—India’s stance is in part reminiscent of its strategy of non-alignment throughout the Cold War. During the bipolar confrontation between the US and Russia, India adopted a position of foreign policy autonomy, rather than relationally or ideologically becoming beholden to one camp.[18]

Even today, despite being a pillar of the so-called ‘Quad’ regional relationship between Australia, Japan, and the US,[19] India’s stewardship of a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ does not render it a servant of the US. Indeed, despite its active diplomatic and commercial dialogue with the US, India continues to import record volumes of Russian crude oil,[20] despite demands from the Biden administration to curtail such imports.[21]

Additionally, as India is set to achieve extraordinary dynamism of wealth creation and prosperity imbedded in the economic forecasts noted above, it may also face geopolitical challenges with the US over the medium- to longer-term, as such income generation in India is likely to be set in contrast with the continued decline of the American middle class. To put it simply: by some politicians in the US, economic security is often mistakenly viewed as a zero-sum game, according to which the gains of one country (read: Japan in the 1980s, and China in the 2000s) are often correlated with a corresponding loss of livelihood for segments of the domestic population in the US.

Accordingly, to the extent that continuing trade and cross-border economic activity supports Indian growth, Indian policymakers, diplomats, and executives should adroitly engage in dialogue with their American (and perhaps even European) counterparts regarding the “benefits of interdependence.”[22] Otherwise, an unintended consequence of India’s increasing prosperity might be to render it a subject of ire in American policy circles over the medium to longer term.

Japan: The Exemplary Foreign Investor

While much of the attention on India’s favourable geostrategic position tends to be discussed in light of its relationship with the US or China, another country presents an ideal example for others to follow with a horizon for long-term value creation in India—Japan. Indeed, a facet of the strong relationship between the late Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi[23] has been that of a favourable position for Japanese companies and investors capitalising on long-term growth prospects in India. Japan has been an active infrastructure investor in India;[24] while some of its major banks continue to deepen their stance within the Indian financial sector.[25] One of its leading industrial companies is currently expanding its investments in India in order to instill greater supply chain flexibility,[26] as well as—ostensibly—to be closer to a growing customer base.

Such active investment by Japan’s government entities[27]—into critical sectors such as affordable housing and low carbon infrastructure[28]—and its leading companies is rooted in the benefits of a true collaborative relationship between the two countries, one of mutual benefit. Although many of these investments are couched in the language of the Indo-Pacific framework, part of Japanese corporate investment into India can also be seen as an unemotional pursuit of growth (as opposed to a fraught or charged repositioning away from China). Such commercial ties will hopefully be augmented by renewed shuttle diplomacy between current Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and Modi, all in a pursuit of a ‘butter over guns’ mentality.

Sectors of Opportunity: Reform-minded Investing

In considering the brightest sectors for long-term investment in India, as noted above, some of the industries currently beckoning large reforms present substantial opportunities. As the outlook for grain production increases in India,[29] so do the prospects for investing up and down the food system, particularly in food storage and AgTech.[30]

As India assumes the presidency of the G20, its avowed focus on decarbonisation[31] will also naturally spur opportunities across the energy and infrastructure space, both in instilling greater efficiencies in traditional forms of energy and in the electrification of transport. In fact, in a marriage of the promising outlook for private consumption and low carbon transport, one local electric motorbike company has recently attracted investment from a prominent US venture capital arm[32]—an industry likely set to blossom as India has a goal of reaching 30 percent of electrification of transport by 2030.[33]

Such reforms are set within the wider global trend of the return of industrial policy: in the emergence from the pandemic—and amidst the backdrop of the energy crisis, and ongoing trade tensions between the US and China—politicians have prioritised growth, investment, and job creation in critical sectors including advanced manufacturing, AI and cloud computing, and innovation in the energy transition. As India progresses along the tech manufacturing spectrum, and ostensibly attracts supply chain activity diverted from China,[34] investors will do well to follow such signals, which are likely to be supported by governments over the medium to longer term.

Conclusion

In sum, the investor spotlight shining on India is indeed merited. In secular terms, as India’s economy and employment base grow from agrarian activity to manufacturing and to services, likely so, too, will the domestic consumption base steadily grow and expand. The potential for this consumption story has been tested during the twinned health and economic crises of COVID-19, as well as from the geopolitical spillovers from the Russia-Ukraine conflict (resulting in higher inflation, and thus diminished purchasing power). Although Indian policymakers confront a host of challenges in both the short and medium term, the very sectors ripe for reforms—including agriculture, energy, and transport—correspond to direct opportunities for long-term, patient capital from private equity, venture capital, and institutional investors.

India’s robust macroeconomic position is further augmented by its geographical position, and stance of relative autonomy amidst a fragmented world. In considering the deployment of capital to Asia, and set against the backdrop of what may likely be the unfurling technological decoupling between the US and China, India continues to magnetise foreign capital for the long duration, and increasingly in the tech manufacturing space. And yet, while the world often focuses on the US, it is actually Japan that has set an example as a model way of commercial and diplomatic engagement in India, in terms of mutual benefit, and prioritising the value creation—rather than defence characteristics—of minilateralism. In such a way, investments by the Japanese government and by its leading corporations have the potential to spur a positive feedback loop, further cementing the conditions for sustainable economic growth, as well as serving as a role model for other countries seeking to create long term value in India.

Endnotes

[a] Private consumption supports some 60 percent of GDP in India, providing a positive feedback loop to longer term growth.

[b] India’s fast moving consumer goods market expanding by 16 percent in 2021, with sustained double-digit growth in 2022.

[c] Defined as the value of foreign assets held by a country, less the value of its own domestic assets owned by foreigners.

[d] Including, but not limited to, the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and the ‘Make in India’ manufacturing campaign.

[1] International Monetary Fund, “Transcript of October 2022 MD Kristalina Georgieva Press Briefing on GPA,” October 13, 2022, IMF.

[3] Shuo Xu, “Performance-Leadership Change and Market Fundamentals,” MSCI.

[4] “MSCI India Index,” MSCI.

[5] Ashutosh Joshi and Akshay Chinchalkar, “Foreign Investor Bets Show Indian Stocks Rally Has More Legs,” Bloomberg, November 28, 2022.

[6] Michael Debabrata Patra, “Geopolitical spillovers and the Indian economy” (speech, New Delhi, June 24, 2022), Bank for International Settlements, https://www.bis.org/review/r220624e.pdf

[7] World Bank, Foreign direct investment, net flows (BoP, current US$), World Bank Group, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.CD.WD?view=map

[8] Nalin Patel, Meghna Jain and Antrikch Rastogi, “India’s Consumer Goods Market Drives Growth In the Post-COVID Era,” Site Selection, November 2022; “FMCG in India continues to recover with double-digit growth in Q2 2022,” NielsenIQ, September 1, 2022.

[9] “India GDP Annual Growth Rate,” Trading Economics.

[10] Carlos Cantú, Paolo Cavallino, Fiorella De Fiore and James Yetman, “A global database on central banks’ monetary responses to Covid-19,” BIS Working Papers No. 934, March 2021.

[11] IMF, “Transcript of October 2022 MD Kristalina Georgieva Press Briefing on GPA”

[12] Lee Ying Shan, “India may become the third largest economy by 2030, overtaking Japan and Germany,” CNBC, December 1, 2022.

[13] Shan, “India may become the third largest economy by 2030, overtaking Japan and Germany”

[14] “China vs. India – Where is the momentum in consumer spending?,” World Data Lab, April 16, 2021.

[15] “A democratic cacophony,” University of Cambridge, October 23, 2015.

[16] Gurcharan Das, India Unbound (New Delhi: Penguin Random House India, 2015)

[17] Mihir Sharma, Restart:The Last Chance for the Indian Economy (New Delhi: Penguin Random House India, 2015)

[18] Kanti Bajpai, “India: Modified Structuralism,” in Asian Security Practice: Material and Ideational Influences, ed Muthiah Alagappa, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998)

[19] Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australian Government, Quad.

[20] James Cockayne and Megan Byrne, “India Crude Imports: Russia Volumes Surge To New Record,” Mees, December 2, 2022.

[21] Steve Holland and Trevor Hunnicutt, “Biden to Modi: Buying more Russian oil is not in India’s interest,” Reuters, April 12, 2022.

[22] Ken Moriyasu, Mariko Kodaki, and Shigesaburo Okumura, “Inside the Trilateral Commission: Power elites grapple with China’s rise,” Nikkei Asia, November 23, 2022.

[23] Manjari Chatterjee Miller, “India’s Special Relationship With Abe Shinzo,” July 14, 2022.

[24] Rupakjyoti Borah, “Japan’s Infrastructure Investment in Northeast India,” The Diplomat, February 8, 2022.

[25] https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Finance/Japan-s-Sumitomo-Mitsui-to-buy-major-Indian-lender-for-2bn

[26] “Japan’s Sumitomo Mitsui to buy major Indian lender for $2bn,” Nikkei Asia, July 6, 2021.

[27] Subhash Narayan & Shashank Mattoo, “Japan’s JICA looks to step up investments in private sector projects in India,” Mint, October 19, 2022.

[28] Japan Bank for International Cooperation.

[29] Michael Debabrata Patra, “Geopolitical spillovers and the Indian economy” (speech, New Delhi, June 24, 2022), Bank for International Settlements.

[30] Alexis Crow, “Annual Outlook 2021: Silver Linings,” ORF Special Report No. 128, January 2021.

[31] Saul Elbein, “India shakes up global approach to climate change as G20 chair,” The Hill, December 1, 2022.

[32] “India’s Ultraviolette Automotive raises funding from Qualcomm,” Nikkei Asia, November 25, 2022.

[33] Abishur Prakash, “Sustainability has brought a new dimension to Asia’s geopolitics,” Nikkei Asia, November 25, 2022.

[34] Chloe Cornish, “India chases dividend from China trade tensions,” Financial Times, December 20, 2022.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr Alexis Crow is Partner and Chief Economist of PwC US. A global economist who focuses on geopolitics and long-term investing, she works with the ...

Read More +