Technology is fast becoming a fulcrum issue in international geopolitics. Securing supply chains, critical tech such as semiconductors, building domestic capacities to hedge over-reliance on others (including allies), have all come to fore as new dynamics at play. For India’s outreach to West Asia, this could become a new area of contestation.

The

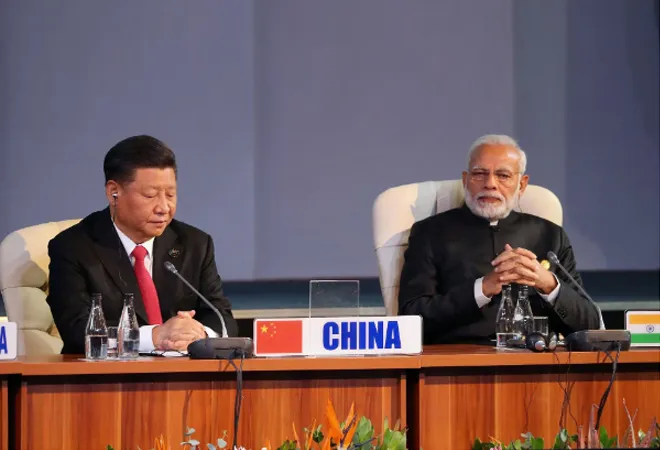

recent expansion of the BRICS consortium to add Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Iran, and Egypt as permanent members shows Beijing’s footprints across such multilateral forums. Considering BRICS has not achieved much since its last expansion in 2010 with the addition of South Africa, this second expansion was made possible in a large part due to the

peace deal between Riyadh and Tehran brokered by Beijing earlier this year. BRICS is set to be another venue for

Indo-Sino contestations under a garb of collaboration.

A wider West Asian region stretching from Iran to Israel and everything in the middle is witnessing fast movements when it comes to securing future technologies. The reasons behind this ‘tech rush’ are a plenty, ranging from an anchoring role of technology in all upcoming economic designs, from energy and food security, and delivering effective governance to developing robust defence equipment that stands the test of time in the coming decades.

A wider West Asian region stretching from Iran to Israel and everything in the middle is witnessing fast movements when it comes to securing future technologies.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia, among others, are increasingly looking to diversify their long-standing geopolitical moorings — that is decades long security partnership with the United States (US) — to secure these investments that are not shackled by terms and conditions, specifically when it comes to issues such as human rights, democracy, and other ideological demands that are often sought by Western states. One of the most prevalent alternatives today offering access to such technologies with very few strings attached is China.

China in West Asia

One report recently

highlighted that Saudi Arabia was becoming an attractive destination for Chinese engineers and experts working on artificial intelligence (AI) who are today unable to access the US job market. On the defence side,

Chinese firms have successfully sold armed drones and light aircraft to the UAE, allowing Abu Dhabi to bypass concerns and roadblocks faced by within the US Congress which has a powerful say in export of such equipment.

Chinese technology companies, such as Huawei, today are important stakeholders in building many projects directly aligned with the Gulf’s critical tech infrastructure for the future. In April,

Huawei hinted towards its willingness in setting up its West Asian headquarters in Saudi Arabia. Friction between the US and the UAE over sale of high-tech defence equipment, including the currently

stalled deal for top-of-the-line F-35 fighter aircraft, is at least in part due to the increasing proximity of US defence equipment to China-provided technology hardware and software.

These trends are not exclusive to Saudi Arabia and the UAE; even smaller regional states such as Bahrain, Kuwait, and Qatar have been increasingly open to co-operation and trade with Beijing, specifically in the tech sector.

Economic overhaul

China’s approach towards the region has increasingly become bolder. This is not necessarily only due to Xi Jinping’s strategic designs, but also how the likes of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, UAE’s President Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan along with other regional leaders are looking at the unravelling of a post-WWII order being pushed through by the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s war against Ukraine, and the view of an incoming Cold War-like US-China rivalry.

Friction between the US and the UAE over sale of high-tech defence equipment, including the currently stalled deal for top-of-the-line F-35 fighter aircraft, is at least in part due to the increasing proximity of US defence equipment to China-provided technology hardware and software.

From the vantage point of these Arab states, many have launched blueprints of major overhaul of their economies with an aim to move away from a stark dependency on hydrocarbons to building their own services, manufacturing, tech sectors, and market themselves as new centres of global finance. While oil will continue to play a defining role in this transition, investing abroad, and attracting business into the region relies on long-term political stability, something that has been historically elusive to achieve in the region.

Challenge for India

For India, the above pose new challenges. Economies such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia have come forward as premier partners for India, however, China’s incremental gains and acceptance there, specifically in the tech sectors, has potential to re-draw lines of economic conservatism. Formation of economic co-operation-led ‘minilateral’ groups such as the I2U2 (Israel-India-UAE-US) have a strong tinge in their construct to both, push back on China’s influence while simultaneously keep the US involved.

India’s view on Chinese companies such as Huawei, among many others, has been aggressive to make sure they are not integrated into the country’s economic infrastructures. After

the border skirmishes in 2020, China’s view within India’s public opinion and perception has drastically tanked, making punitive measures against Beijing from an economic perspective more palatable while remaining realistic about the lop sidedness of bilateral trade between the two which continued to stand in China’s favour at

$135.98 billion in 2022.

Formation of economic co-operation-led ‘minilateral’ groups such as the I2U2 (Israel-India-UAE-US) have a strong tinge in their construct to both, push back on China’s influence while simultaneously keep the US involved.

While India’s diplomatic and political outreach with West Asia has been a success story over the past decade, the geopolitics of technology has the potential to offer a challenge. West Asia’s courtship with China is basically arrival of the concept of strategic autonomy, hedging their bets, and spreading risk — all strategies also employed by India to pursue its own national interests.

However, in this case, while pursuing the same concept, the strategic aims are divergent. States in West Asia collaborating more with China instead of ‘de-risking’, will demand a versatile diplomacy tool kit to make sure clean borders are drawn between advent of Chinese tech there and its potential after-effects here, without disturbing the positive India-West Asia economic story.

This commentary originally appeared in Deccan Herald.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.