The deaths of

22 jawans in an encounter with the Maoists in Bijapur, Chhattisgarh came as a huge shock for India and its security forces. The usual questions of intelligence failures, forces making tactical mistakes, and not following up standard operating procedures have been raised by experts and analysts. These are very pertinent questions given this was a massive combing operation jointly conducted by the elite CoBRA unit of the Central Reserve Police Force, Special Task Force, District Reserve Guard, and District Force of Chhattisgarh Police to attack and capture Hidma, the commander of the lethal Battalion 1 of the Maoists. How did such a planned counterinsurgency operation based on prior intelligence inputs fail to anticipate an ambush by the Maoists?

Not strong enough

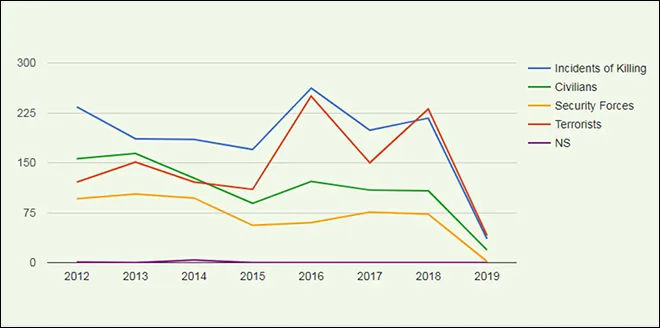

The irony is that a massacre of this scale happened at a juncture when the security forces have acquired better combat experience and are in a dominant position compared to the Maoists. The year 2019 (see below graph) saw one of lowest fatalities among security forces in the last two decades. A coordinated and well-calibrated counterinsurgency operation by the Centre and affected states have helped to bring down Maoist sponsored violence to an all-time low, reducing their dominance to few

tri-junction districts of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Odisha. Unsurprisingly, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA)

removed 44 districts from the Naxal-affected list, while the ‘worst-affected category’ was brought down to 30 in 2019. According to

ACLED data, Maoist-related incidents in 2020 took even bigger dip (30 per cent less) than 2019 due the Covid-19 pandemic. The

national lockdown proved a massive blow for Maoists, as it cut critical supplies for many months and pushed them to desperation.

Maoist-related fatalities | Source: Author’s own estimation from multiple sources.

Maoist-related fatalities | Source: Author’s own estimation from multiple sources.

The once-formidable insurgency appears very weak and dispirited as the group is experiencing deep fissures within. Its top leadership is getting thinner every day. The security forces have succeeded in capturing more than 8,000 active cadres in the last four years, while an equal number of Maoists have surrendered before authorities. According to

Ganapathi, the top Maoist leader who retired recently, the Maoist organisation has had no new recruits in the past decade, and it has lost its hold over many liberated zones.

Practically, the Maoist organisation’s presence is limited to the Bastar region with an area of 40,000 square kilometer. This is a phenomenal achievement considering that a decade ago India was staring at an insurgency that was spreading like rapid-fire and held sway over one-third of its territories.

Therefore, while it is necessary to go to the drawing room and seriously assess what went wrong with the combing operations in Bijapur and how a repeat of any such incident can be best avoided, there is no need to give in to the war cry that has taken over social media. Revenge has no place in counterinsurgency. This is a long-drawn battle, and any rush to deploy more forces and launch an all-out offensive may bring with it huge humanitarian costs. This is precisely the mistake the ultras want the security forces to commit.

Change the approach

The Chhattisgarh experience demands an urgent revisiting of the existing counterinsurgency strategy that lays excessive focus on a security-centric approach. Years of a persistent security-centric approach to capture the Maoist fortress (Bastar) has not yielded any significant positive results. Rather, it has brought more casualties among forces. Based on

global counterinsurgency experience, the most appropriate thing at this juncture would be to open the channels for political dialogues with Maoists. Therefore, a solution cannot be found in a security approach alone. Proof lies in its five-decade-long existence notwithstanding the State offensives. And the best time to have a peace dialogue with insurgency anywhere is when they are weak.

All evidence suggests the Maoist organisation is considerably weaker and have their back against the wall. It is here the Indian State can take a leaf from the successful negotiation by the Columbia government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC. If the Columbia government can engage in dialogue with the world’s most dreaded Left-wing insurgency, which has

taken 260,000 lives and displaced more than 6.9 million people in less than six decades, a democratic India should not shy away from trying this option too. In fact, with their domination being very weak and confidence low, rebels might be much more eager for political dialogue than ever before.

While the Maoist leadership has avoided dialogues in the past, they did this during the peak of their domination. The Columbia

lesson can come handy here. Only after liquidating most top leaders and pushing FARC to the margins could the Colombia government prevail over the rebels. FARC leadership resisted the government’s offers for many years, yet with persistent efforts and their movement losing its popular appeal forced it to agree to a truce.

We have seen the end of a decade-long insurgency in our own neighbourhood with Nepal. It was through political negotiation that this violent Left-wing insurgency was

brought to an end in 2006. Therefore, the opening up of democratic process is crucial.

Will a nationalist government that perceives political dialogues or peace overtures as a sign of ‘weakness’ rise to grab the opportunity? This is highly unlikely considering the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government has consistently projected national security through a muscular approach. There is an unprecedented level of

politicisation of national security, evident in the use of ‘surgical strikes’ and other covert operations for political gains. The peace process would require the critical roles of civil society actors, expect now they have been branded ‘Urban Naxals’.

Still, all is not lost. The Chhattisgarh government is well placed to initiate this dialogue as well. To its advantage, a robust civil society conglomeration from Raipur recently organised a peace march — ‘

Dandi March 2.0’ — appealing for political dialogue and an end to violence. Hundreds of participants covered the 222-kilometre peace rally for 11 days. In short, time is ripe for exploring an unconventional approach to end the five-decades-long insurgency. Armed means alone cannot crush a revolutionary movement that draws its roots from underdevelopment, injustice, exclusion and lack of governance.

This commentary originally appeared in The Print.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

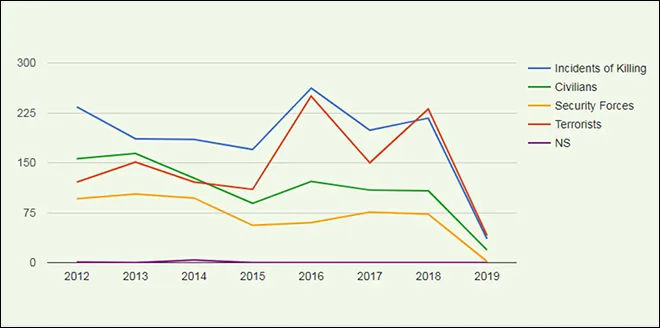

Maoist-related fatalities | Source: Author’s own estimation from multiple sources.

Maoist-related fatalities | Source: Author’s own estimation from multiple sources. PREV

PREV