Introduction

Like in most federal countries[i] in the world, healthcare in India is listed as a State subject—meaning that states are the primary agents tasked to deliver health-related services. For India, this setup has met with various issues as under existing federal arrangements, states are not vested with adequate financial powers to meet their expenditure responsibilities. After all, the Centre holds maximum control over tax revenues. The pathway to bridge such gaps is through loans and intergovernmental transfers (from various central ministries to states and local governments). This apart, as most federal countries routinely do, the central government makes specific-purpose transfers or grants on critical areas such as health and education. For example, the Union Government runs the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), one of the largest healthcare programs in the country catering to the health needs of the rural poor. Of course, states have their own resources to design and implement social schemes in their own ways.[ii]Beyond finance, the federal government plays a dominant role in the setting up and management of institutions, health infrastructure and policies—such architecture creates an impact on the state’s health outcomes which, in turn, affect the country’s overall ranking in healthcare. It is the federal government that frames and anchors a wide variety of national programs such as those concerned with diseases like leprosy, malaria, polio, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS.

Thus, the current power sharing arrangement between the centre and states is such that the federal government carries the most responsibility in decision-making. How has this addressed the issues of access, equity and regional inequalities in healthcare? Has the multiple levels of intergovernmental transfers—in particular, the specific-purpose transfers to the health sector—achieved the desired goals? To be sure, these central transfers have many positive effects in terms of creating institution, building infrastructure and improving healthcare delivery, particularly under NRHM.[iii] Evidence suggest, however, that the federal transfers architecture has generally failed the country’s healthcare system. Proof of this is the country’s poor showing in key health indicators. In fact, many of India’s poorer neighbouring countries perform better on several indicators. Given that the states are mostly in-charge of program implementation (besides shouldering the bulk of the financial burden) they are to be held accountable for the country’s poor performance in key health parameters. But this paper’s aim is not to pin the blame solely on either the Centre or the States for the challenges facing the country’s healthcare; rather, the imperative is to examine the current institutional architecture for healthcare.

This paper seeks to understand the correlation between India’s federal system, existing inter-governmental mechanisms for resource transfers, and policies and schemes to achieve health goals. It also studies the likely implications of the recommendations made by the Fourteenth Finance Commission (FFC) on health outlays.

Healthcare in India: A Snapshot

The opening words of the draft National Health Policy (NHP) 2015 perhaps best illustrate the state of healthcare in the country: “India today, is the world’s third largest economy in terms of its Gross National Income (in PPP terms) and has the potential to grow larger and more equitably, and to emerge to be counted as one of the developed nations of the world. India today possesses as never before, a sophisticated arsenal of interventions, technologies and knowledge required for providing health care to her people. Yet the gaps in health outcomes continue to widen. On the face of it, much of the ill health, disease, premature death, and suffering we see on such a large scale is needless, given the availability of effective and affordable interventions for prevention and treatment.”[iv]

This is not to say that there has been no progress at all in India’s healthcare. Indeed, gains have been achieved in certain health areas;[v] the overall picture, however, is that of a nation that remains beset with huge challenges. For example, the proportion of underweight children in India has gone down from 53.5 percent in the 1990s to 40 percent in 2015. However, this performance is well below the global goal of 26 percent. Similarly, India has missed—by a significant 65 points—the Millennium Development Goal for maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of 109 per 100,000 live births by 2015.[vi]

India’s performance in infant mortality rate (IMR) has also been below par, at 38 per 1000 live births. The country’s poorer neighbours have achieved more in this area: for Bangladesh and Nepal, IMR is much lower at 33 and 32 per 1000 live births, respectively (see Table 1).

India’s performance varies across states and regions. For instance, the difference in infant mortality rate between the best-performing state of Goa and the worst performing states (Madhya Pradesh and Assam) is nearly six-fold. Further, sharp variations are to be found across social groups. The dalit and adivasi, for example, are over-represented among India’s undernourished children.[vii]

Among the primary reasons for the country’s poor showing on health is the continued low levels of public spending, which today represents less than 30 percent of total health spending. This represents only about 1.04 percent of GDP, which is approximately 4 percent of total government expenditure. Numerically, this translates to INR 957 per capita at current market prices. The Central Government share of this is INR 325 (0.34 percent of GDP) while State Government share translates to Some INR 632 per capita at baseline scenario. Global evidence on health spending suggests that unless a country spends at least five to six percent of its GDP on healthcare—and the major part of it is from government expenditure—basic healthcare needs are rarely fulfilled.[viii]

Other factors that contribute to underachievement in health include flawed policies, a lack of capacity, inefficiency, and the weak execution of programmes. Corruption worsens the situation further.[ix] Yet very few analysts talk about the institutional and political aspects contributing to the poor delivery of healthcare services in the country. In many ways, India’s ailing healthcare system has roots that go deeper into the country’s federal system, the inter-governmental transfers system, and centralised policies and schemes.

Table1: Key Health Indicators: India vs. Neighbours

| Indicator |

India |

China |

Bangladesh |

Sri Lanka |

Pakistan |

Brazil |

Nepal |

| Infant Mortality Rate (per 1000 live births) |

38 |

9 |

31 |

8 |

66 |

15 |

29 |

| Under-5 Mortality rate (per 1000 live births) |

48 |

11 |

38 |

10 |

81 |

16 |

36 |

| Maternal mortality ratio (per 100,000 live births) |

174 |

27 |

176 |

30 |

178 |

44 |

258 |

| Per capita government expenditure on health (PPP, $) |

75 |

420 |

31 |

127 |

36 |

947 |

40 |

| Out-of-pocket health expenditure |

89.2 |

72.3 |

92.9 |

95.8 |

86.8 |

47.2 |

79.9 |

Source: World Health Statistics Report, 2015 and The World Bank Data 2015.

Healthcare and India’s Federal System: Issues and Challenges

The Constitution of India defines the distribution of power between the Centre and the States under various heads, namely, legislative, administrative and executive. The legislative section is divided into three lists: Union list; State list; and Concurrent list. The Union list consists of 99 items on which the parliament has exclusive power. The State list consists of 61 items on which state legislature has exclusive power to make laws, and the Concurrent list has 52 items of joint responsibility.[x] Healthcare belongs to the State list: it is the states that carry the primary responsibility to deliver health-related services.

At the same time, however, states are not vested with adequate financial powers to meet their expenditure responsibilities. At present, States raise about 38-40 percent of total current revenues, while they incur on an average 58-60 percent expenditure on a range of items including health and family welfare.[xi] Such vertical fiscal imbalance (limited tax bases with maximum expenditure responsibility)—which is in-built in the original constitutional design[xii]—is addressed through the inter-governmental transfers carried out via multiple channels, mainly the Finance Commission (FC), the Planning Commission (PC)[xiii]and various central ministries. Of these, the Finance Commission plays the pivotal role. Appointed every five years, the FC is vested with powers to recommend the shares of personal income tax and union excise duty and grants-in-aid to the states. The transfers through the FC consist of general purpose transfers (formula-based tax devolution and block grants), specific purpose transfers (education, health), and state-specific grants (disaster relief and special needs).[xiv] Overall, The FC’s primary role is to recommend resource transfers aimed at correcting the vertical and horizontal fiscal imbalances in an equitable and efficient manner.[xv]

The second major source of transfers to states are plan grants and loans mainly by the Planning Commission (abolished in 2014) to meet non-plan requirements in the current account.[xvi] Although a large chunk of such transfers are discretionary in nature, like the FC, the PC too disbursed funds mostly on the basis of a formula (the Gadgil-Mukherjee formula)[xvii] mainly to bridge regional imbalances and address specific needs of the states concerned. Besides these two important channels, various Central ministries provide specific-purpose transfers to states to bridge financial gaps and to help states improve their key human development indicators (such as health, education, food security, and social safety). These transfers are carried out in the form of centrally sponsored schemes (CSS) to address issues of regional imbalances and income inequality, and promote cross-learning among states. On health alone, the Centre runs a number of flagship programmes such as the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) and Rashtriya Swastha Bima Yojana (RSBY). There are also large programmes being managed by the Centre, like the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), which directly bear on health.

Beyond the instruments of central transfers, the federal government also dominates the policy and program architecture concerning the health sector in various other ways. Constitutionally speaking, the Centre’s dominance stems from the fact that while public health and sanitation, and hospitals, for example, are within the domains of the states, the tasks related to “population control and family planning” (Entry 20A), “legal, medical and other professions” (Entry 26) are in the “concurrent list”—which means they fall under the jurisdiction of the Union Government. Moreover, institutions and organisations declared by parliament to be of national importance and institutions for professional and technical training and research come under the purview of the Union Government.[xviii] As a consequence, key policies and the planning framework for the health sector have been provided by the Central government, contrary to the response of most federal countries. In the real sense, it is the federal government that frames and anchors various national programmes (such as vertical programmes for leprosy, tuberculosis, blindness, malaria, smallpox, diarrhoea, filaria, goitre and HIV/AIDS) in which the states have little say in deciding the design and components. This, in some sense, goes against the spirit of “cooperative federalism”[xix] as it distorts the principles of subsidiarity. The larger question is this: Has such a Constitutional arrangement effectively addressed the issues of access, equity and regional inequalities in healthcare?

Scholars and health policymakers in India are generally in agreement about the benefits of the current system of transfers and policy architecture dominated by the Centre. As has been brought out recently by the draft National Health Policy 2015, the central transfers and policy interventions in the past decades have led to some spectacular achievements on polio eradication, as well as in arresting the high rates of MMR and IMR. The flagship healthcare programs, particularly NRHM, established through specific-purpose transfers have helped improve maternal and neonatal health by the promotion of institutional deliveries.[xx] Yet the existing system of transfers and institutional arrangements have not achieved much, particularly with regard to key health indicators and more particularly in bridging widening inter-state disparities and wide variation among different sections of population as prominently acknowledged in the draft NHP 2015. The fiscal transfers system (particularly the specific-purpose transfers) have failed to reduce “the substantial and persistent inequalities” in health expenditure and outcomes across Indian states.

The recent working group report of the US-based Centre for Global Development (CGD) and Accountability Initiative (India) which made an in-depth examination of 12th and 13th Finance Commissions and NRHM found several weaknesses and unintended consequences with regard to specific-purpose transfers.[xxi] For instance, the 12th Finance Commission which had recommended health-specific transfers (known as equalisation grants for health) for seven states having the lowest health indicators proved less than successful. Stiff conditions attached to such transfers proved problematic and a record 20 percent of the funds remained unutilised by these states. Similarly, the 13th Finance Commission’s health-specific transfers which were conditional on states reducing their infant mortality rates, met with similar fate as the 12th FC. A handful of states with better baseline data on infant mortality captured most of the benefits.[xxii]

Similarly, NRHM[xxiii]—which came about via specific purpose grant in 2005 to improve access to effective healthcare for rural poor in 18 high-focus states—has not been able to live up to expectations. To be sure, the program has contributed to the creation of a health workforce of 900,000 community volunteers and has added 178,000 personnel to the regular public health system workforce. NRHM has also resulted in critical health infrastructures and design innovations, as reported in the draft NHP 2015. However, the failures far outweigh these benefits. While the program has had a visible positive impact on 18 “high-focus states” in reducing their IMR and MMR rates, the overall objective of “bridging widening health disparities among states” still remain unfulfilled.[xxiv] Analysts point to many reasons for the under-performance of the program, among them, NRHM’s ‘one-size-fits-all approach’ in high-focus states which does not recognise the socio-economic diversity of needs. Also a constraint is the program’s requirement for high-focus states to match allocated transfers with their own contribution.[xxv] Data show that there are low-income states which often find it difficult to arrange for this contribution, and therefore are unable to claim the transfers.[xxvi]

The above review suggests that the existing fiscal transfer architecture, with its fragmented approach (multiple channels of transfers) has not served the health sector well. Aside from the fact that the central transfers to health-related expenditure remain low (at only 0.34 percent of GDP), the more important issue is the existing transfer system which has reduced the fiscal space of states and failed to offset their fiscal imbalances fully (as reflected in the strong correlation between per-capita health spending and income levels across states.[xxvii]) The system needs major fine-tuning. With the enactment of the Fiscal Responsibility law (enacted in 2003 but operational since 2007) that provides for stiff restrictions over spending, states need bigger central transfers that are less fragmented and incentive-compatible.

Prospects After 14th Finance Commission’s Devolution

The Union Government’s acceptance of FFC recommendations in 2015 holds much promise to reset the existing fiscal transfers system mired by fragmentation and arbitrariness. The FFC’s recommendation of 42-percent tax devolution to the states is widely seen to be a game-changer. According to one estimate,[xxviii] 29 states would have about $20 billion[xxix] per year to prioritise and spend on their own. This is because a bulk of these transfers are untied funds. Preliminary assessments have shown that the FFC devolution has resulted in a significant increase in the share of untied funds available for states (rising from 20 to 30 percent).[xxx]

It is presumed that fiscal devolution of such magnitude would significantly address the issue of fragmentation in fiscal transfers (following the abolition of the Planning Commission) while enhancing fiscal space at the sub-national level. Importantly, several analysts[xxxi] believe that such bold decision by the Central government to accept FFC’s devolution proposals would have a dramatic impact on improving the spending on social sectors particularly in key provisions such as healthcare, nutrition and education. Importantly, there is huge expectation that such flow of untied funds to states (considering most states have enhanced their healthcare expenditure in the last decade[xxxii]) will have a positive effect on the country’s healthcare expenditure, which at present hovers just above 1 percent of GDP.

Important questions remain: Will more funds channelled to states in fact lead to greater allocations to healthcare? What would be the net outcome of the Centre’s scrapping of many flagship schemes[xxxiii] on key social sector expenditure by states, even if the monies for the same are transferred to states? It must be noted that the Union Government, under the stewardship of NITI Aayog, had constituted a Sub-Group of Chief Ministers to deliberate this issue of rationalising Centrally Sponsored Schemes.[xxxiv] A review of activities at the state level shows mixed trends.

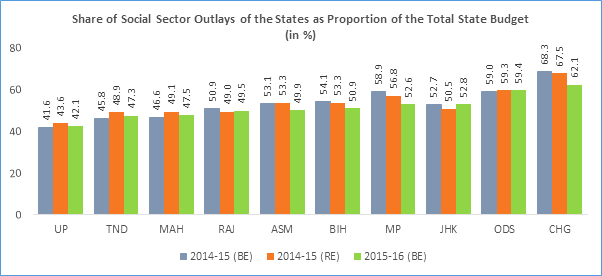

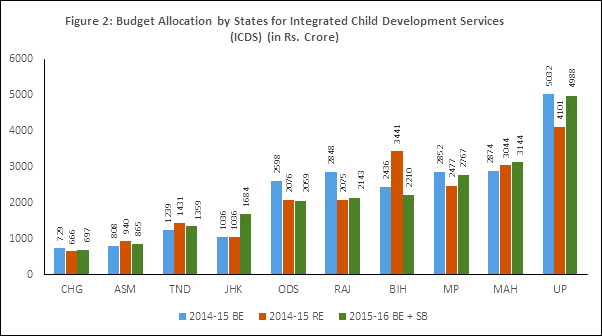

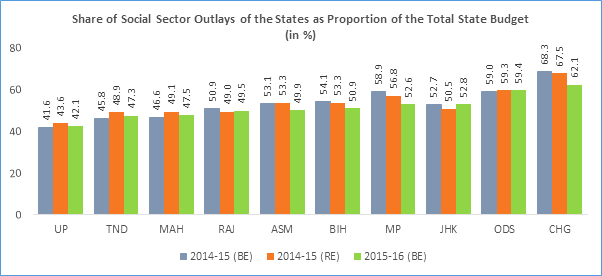

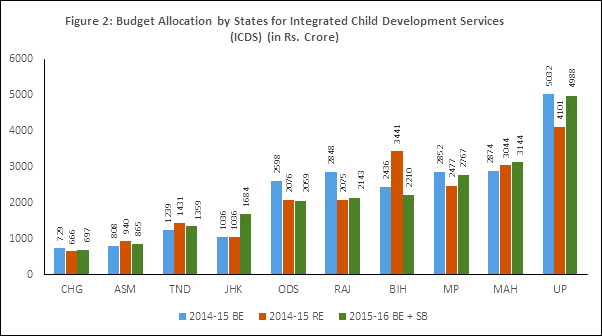

One, while the expenditure on social services as a proportion of total state government expenditure has gone up modestly from 36.1 percent in 2014-15 to 38.2 percent in 2015-16 after FFC’s devolution,[xxxv] this only reveals half the story. Such macro positive trend hides plenty of issues involving sub-sectoral allocations and expenditure which varies across states. For instance, take the case of allocation to the National Health Mission (NHM), a major programme designed to improve general health indicators in the country. Following the FFC devolution, it was assumed that states would increase their allocation for the NHM. Yet data from the last two years indicate that except for Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Tamil Nadu, all other states under the study have increased their allocation only marginally.[xxxvi] Similarly, the allocation for ICDS by states declined in 2015-16 in the case of Odisha, Rajasthan, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh (See Figure 2). While a general statement cannot be made from these illustrations, they nonetheless provide some room for rethinking.

Figure 1

Source: Based on data compiled by CBGA from various State Budget Documents. Note: Social Sector includes Education, Health, Drinking Water and Sanitation, Women and Child Development, Social Welfare (excluding women and child development), Agriculture and allied sectors (Animal Husbandry, Dairy, Fisheries, Cooperation, and Irrigation) Food and Civil Supplies, Rural Development and Panchayati Raj.

Figure 2

Source: CBGA Report, 2016

Two, greater transfers of tax revenues to states (along with greater autonomy and flexibility to prioritise their spending) have not encouraged states to increase their budgetary expenditure on social sector. According to a recent study by the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA),[xxxvii] with the exception of Chhattisgarh, all other nine states under the review have preferred to use the additional revenues to reduce budgetary deficits (See Figure 1) than push their budgetary expenditure particularly for the ailing social sector.[xxxviii]Three, available evidence suggests a different story with regards to greater flow of untied funds to the states and the likelihood of increased spending in critical social sectors such as healthcare, nutrition and education. The availability of more untied funds has failed to result in any significant positive change in expenditure prioritisation in critical sectors such as health and education by the poorer states.[xxxix] As mentioned earlier, notwithstanding the significant rise in untied funds, many states have in fact reduced their allocations to critical programmes such as NHM, Integrated Child Development Services, and Mid-Day Meal schemes.[xl]

Issues of State Capacity

What this paper has shown so far is that greater devolution of funds to the states (and their local governments[xli]) is no guarantee that more monies will be allocated to the relevant social sectors. While critical elements like the quantum of devolution and the state’s financial health would go a long way in stepping up public spending on the social sectors, the most decisive factor is state capacities to spend large, “untied” funds to shore up better outcomes.

There exist huge inequalities in state capacities in terms of financial resources, physical and social infrastructure, and administrative and technical skills among officials.[xlii] The states which lack the required infrastructure, skilled staff, technical expertise and requisite institutions to design and administer large programmes may not gain much from greater devolution. Indeed, devolution might escalate these inter-state inequalities. Incidentally, these are states that have poor records of decentralisation to local-level institutions—the critical agents for effective service delivery. Thus, to provide greater teeth to devolution (by increasing transfers and restructuring centrally sponsored schemes), the Centre needs to do more.

It is here that institutions like NITI Aayog can play a critical role as harbingers of innovative ideas by providing policy as well as support to states that lack in the areas of administration, expertise and requisite technical skills to design and administer large and complex projects in areas like healthcare, education and nutrition. Given its recognition as an in-house think-tank of the central government and a replacement of the erstwhile Planning Commission, NITI Aayog would have to play an extremely critical role. Of course, this would involve not only providing a policy framework for health, but also driving state-level initiatives to deliver on key health goals. In short, the realisation of health targets in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) would hinge on the decisive roles of NITI Aayog and its ability to reduce policy fragmentations at various levels and provide leadership on key health missions.

Conclusion

As India aspires to achieve universal healthcare coverage under the SDGs and to boost Central Government funding for health from 1.4 percent of GDP to 2.5 percent in the near future as stated by the draft NHP 2015, a major health financing choice available is the intergovernmental transfers. While the existing system of transfers, particularly the specific-purpose grants, have shored up several health indicators in the recent years and have made visible contribution to strengthen the country’s public health system, much more is needed to meet certain basic parameters that will bring the country at least at par with other developing nations, and perhaps meet global standards. With non-communicable and lifestyle diseases emerging as a major health challenge and communicable diseases continuing to be a major problem, the federal transfers need an urgent reorganisation. The intergovernmental transfers mechanism with its multiple channels of transfers has over the years eroded the fiscal space of states and made them outside participants in the key policymaking related to healthcare. Despite being the most important cogs in program implementation, states play little role in designing and shaping the contours of centrally sponsored schemes. While NITI Aayog’s recent initiative of constituting a Sub-Committee of Chief Ministers to review centrally funded schemes, the federal government continues to have the last word on policies and programs that ultimately get implemented by the states.

This is set to change in the near future, especially after the Union Government’s recent acceptance of FFC recommendations. As earlier discussed, FFC provides the much needed fresh air to the federal transfers system as, for the first time, states are pumped with large chunks of untied funds to run programs on their own. However, as shown by available evidence from selected states, such transfers would not automatically lead to greater spending on healthcare and other pressing social sector issues. Unless there are clear mechanisms and instruments in place, such flows of extra funds would be of little positive consequences. In this regard, the Centre’s job through the NITI Aayog assumes a critical nature. It cannot be overemphasised that ensuring a minimum standard of basic health services for all—as declared boldly in NHP 2015—would require the Central government’s critical leadership and policy flexibility especially in rearranging existing centre-state transfers system and providing states greater space in policymaking for the health sector. This will also hew with global best practices that make the central government play a significant role in providing quality healthcare to its citizens.

Endnotes

[i]See Govinda Rao and Mita Chowdhury, Health care financing reforms in India, NIPFP Working paper, No. 100, 2012, http://www.nipfp.org.in/media/medialibrary/2013/04/wp_2012_100.pdf

[ii]It must be noted that states in India account for 80% of spending on healthcare. Further, while the federal spending on healthcare has seen a decline in the last few years particularly since 2011-12, states have raised (20-30%) their spending on healthcare. For details see Amanda Glassman and Anit Mukherjee, “Getting Centre-State Relations right for Health in India”, Centre for Global Development blog, January, 2015, http://www.cgdev.org/blog/getting-center-state-relationships-right-health-india

[iii]For instance, without the plan grant and active support of the Planning Commission, India would not have created NRHM which has gone a long way to address several core issues involving healthcare in rural areas. For a detailed reading of federal transfers and their effects, see Govinda Rao et al 2012.

[iv] See National Health Policy (NHP) 2015, Ministry of Family Health and Welfare, Government of India, http://www.mohfw.nic.in/showfile.php?lid=3014

[v]For a positive story on healthcare, see this report: http://www.countdown2015mnch.org/documents/2015Report/India_2015.pdf

[vi] Millennium Development Goals, India Country Report 2015, Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation, Government of India, http://mospi.nic.in/Mospi_New/upload/mdg_26feb15.pdf

[vii] William Joe, Udaya S. Mishra and K. Navnetham, Inter-Group Inequalities in Child Under-nutrition in India: A Gini Co-efficient and Atkinson’s Index, Oxford Development Studies, Vol. 41, June 2013, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13600818.2013.796353?journalCode=cods20

[viii]See National Health Policy (draft) 2015. Ibid.

[ix]For an analysis of reasons behind poor healthcare situation see The High Level Expert Group Report on Universal Health Coverage for India, Planning Commission of India, Government of India, 2011, http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/rep_uhc0812.pdf, also Maureen Lewis, Governance and Corruption in Public Health Care Systems, The World Bank Working Paper , No. 78, Centre for Global Development, The World Bank, January 2006, http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/anticorrupt/Corruption%20WP_78.pdf

[x]Niranjan Sahoo, “Centre-State Relations in India: Time for a New Framework”, ORF Occasional Paper, No. 79, March 2015, https://www.academia.edu/12460985/Centre-state_relations_in_India_Time_for_a_new_framework

[xi] See Govinda Rao et al 2012

[xii]See Subrata Mitra and Malte Pehl, “Federalism”, Niraja G. Jayal and Pratap Mehta (ed.) in Oxford Companion to Politics in India, (New Delhi: Oxford University Press), 2010

[xiii] The Planning commission that was established by the Union Government through an executive order on 15 March 1950 was abolished by the current National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government in 2014. The commission has been replaced by a new institution called National Institution for Transforming India (NITI) Aayog which intends to work as a policy think tank for generating new ideas and innovation in public policies.

[xiv] For an illustration of intergovernmental transfers, see the recent report of Centre for Global Governance, 2015. http://www.cgdev.org/publication/power-states-making-fiscal-transfers-work-better-health

[xv] An illustration of this can be found in M. Govind Rao and Tapas Sen, Federalism and Fiscal Reforms in India, NIPFP Working Paper, No. 84, 2011, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.380.8305&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[xvi]With the abolition of PC in 2014, a lot of plan assistance has been subsumed in the unconditional transfers as per the recommendation of Fourteenth Finance Commission.

[xvii] Until the third Five-Year Plan (1966-69), the allocation of central plan assistance was largely discretionary. However, after a lot of states complained about this, the fourth and fifth Five-Year Plans adopted a formulaic based allocation called Gadgil Formula, named after VR Gadgil, a noted social scientist who pioneered new mode of allocation for special category states. For making allocation, this formula gave 60% weight to population, 10% to per capita income, 10% to tax effort, another 10% to special problems among other. This was, however, amended during the deputy chairmanship of Pranab Mukherjee. The Gadgil Formula was revised and renamed as Gadgil-Mukherjee formula. The new formula gave greater emphasis to tax effort, fiscal management apart from weightage given to population (based on 1971 census). For an excellent illustration of this formula, see Antra Bhatt and Pascuale Scaramozzino, Federal Transfers and Fiscal Discipline in India: An Empirical Evaluation, ADB Economic Working Paper Series, No. 343, March 2013. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/30214/economics-wp-343-federal-transfers-fiscal-discipline-india.pdf

[xviii] Govinda Rao et al 2012

[xix] In his first address to newly constituted NITI Aayog, Prime Minister Narendra Modi used the word “cooperative federalism”. See his message captured by Press Trust of India, “http://pib.nic.in/newsite/mbErel.aspx?relid=115246

[xx] Samarth Bansal, Janani Suraksha Yojana pay dividends, The Hindu, October 10, 2016, http://www.thehindu.com/data/janani-suraksha-yojana-pays-dividends-study/article9204743.ece

[xxi] For an insightful analysis on this, see CGD Report 2016.

[xxii]For instance, a huge 65 percent of allocations going to states that accounted for less than 10 percent of India’s total population. The top three states to gain from this performance-based incentive were three north-eastern states, which already had lower infant mortality rates than other states. Whereas, the formula failed to adequately compensate states that achieved substantial declines in infant mortality and had large populations. Uttar Pradesh reduced its infant mortality rate of more than 10 deaths per 1,000 live births over 2009–12 and has 16.8 percent of the national population, but it received only 0.3 percent of national allocations. Ibid.

[xxiii]Initiated in 2005, NRHM’s main goal was to revamp the public healthcare system “by increasing funding, integration of vertical health and family welfare programs, employment of female accredited social health activities in every village, decentralized health planning, community involvement in health care, strengthening of rural hospitals, providing united funds to health facilities, and mainstreaming traditional systems of medicine into the public health system.” See Srinath Reddy, S. Selvaraj, K.D. Rao, M. Chokshi, P. Kumar, V. Arora, S. Bhokare, and I. Ganguly. “A Critical Assessment of the Existing Health Insurance Models in India.” Public Health Foundation of India. The Planning Commission of India, 2011, http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/sereport/ser/ser_heal1305.pdf

[xxiv] CGD Report 2016.

[xxv] See CGD Report 2016; also see Govinda Rao et al 2012.

[xxvi] Govinda Rao et al 2012, Ibid

[xxvii]Ibid

[xxviii] Anit Mukherjee, Power to the States: Is the Indian model of Fiscal Federalism taking Shape? Global Health Policy Blog, 24 February, 2015, http://www.cgdev.org/blog/power-states-indian-model-fiscal-federalism-taking-shape

[xxix] However, there is catch here. Since the higher magnitude of states’ share in central taxes has come partly at the cost of discontinuation of central assistance for state plans and reduced funding shares of the Union Government in centrally sponsored schemes in a host of sectors, the changes in 2015-16 have led only to a modest increase in the total quantum of resources being transferred from the Union to the states. For more information, see Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA) Report 2016, http://www.cbgaindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/state_budget_Analysis.pdf

[xxx]See the link: http://www.accountabilityindia.in/power-states-making-fiscal-transfers-work-better-health

[xxxi] See Anit Mukherjee et al 2015, op.cit.

[xxxii] In sharp contrast to Union Government’s health spending since 2012-13 which took a major nose dive, spending by states grew at close to double digit rates (9.86%). See T Sundararaman, Indranil Mukhopadhya and V.R. Muraleedharan, “No Respite for Public Health”, Economic and Political Weekly, No. 16, April 16, 2016.

[xxxiii] See an excellent illustration on this by T Sundararaman et al, 2016, ibid.

[xxxiv] See the Report of Sub-Group of chief Ministers, http://niti.gov.in/content/sub-group-chief-ministers.

[xxxv] Avani Kapur,and Srinivas Choudhury, “Budget Briefs 2016:TheState of Social Sector Spending”, http://cprindia.org/research/reports/state-social-sector-expenditure-2015-16.

[xxxvi] CBGA Report, 2016, http://www.cbgaindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/state_budget_Analysis.pdf

[xxxvii] CBGA Report 2016, http://www.cbgaindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/state_budget_Analysis.pdf

[xxxviii]Ibid

[xxxix] Anit Mukherjee, India’s Budget for Health puts Ball in States’ Court, Global Health Policy Blog, January 3, 2016, link: http://www.cgdev.org/blog/indias-budget-health-puts-ball-states-court

[xl] See interesting analysis on some of these dimensions in Karnataka, Pranay Kotasthane and Varun K Ramachandra, “Karnataka’s Changing Fiscal landscape”, Economic and Political Weekly, No. 33, 13 August 2016,

[xli] As per the FFC recommendations, Rs. 287,436 crore (US$48 billion) is slated to be devolved to local governments. Dinesh Mehta and Meera Mehta, “14th Finance Commission: A Trust Based Approach towards Local Government”, Ideas for India, 24 April, 2015. More at: http://www.ideasforindia.in/article.aspx?article_id=1443#sthash.89NaMQ21.dpuf

[xlii]See Patrick Heller, “The Great Transformation of Indian States”, Seminar, No. 620, 2011, http://www.india-seminar.com/2011/620/620_patrick_heller.htm

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV