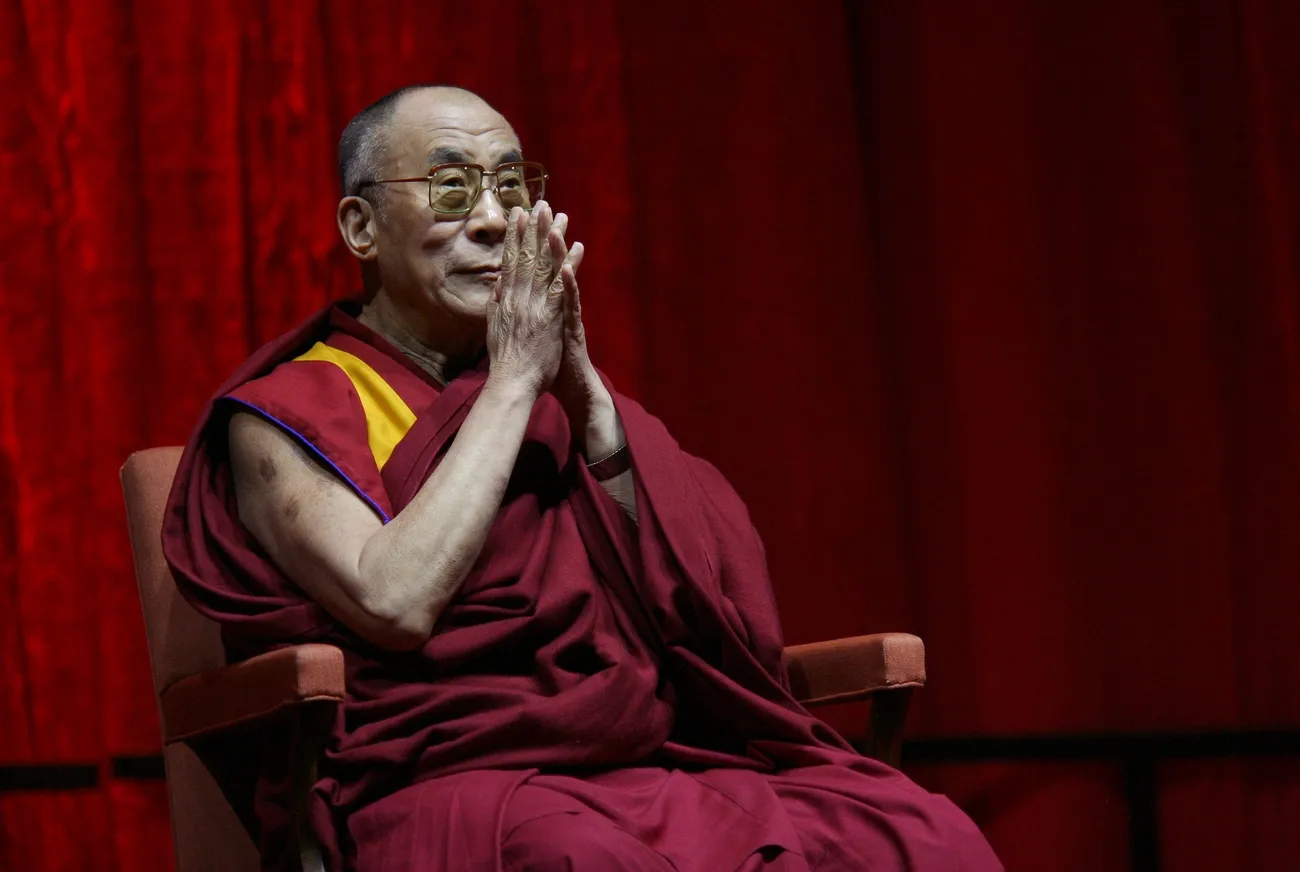

India recently announced that it will welcome the Dalai Lama, the Tibetan spiritual leader who has lived in exile in India since 1959, at an international conference on Buddhism in the state of Bihar in March. Ignoring protests from the Chinese government, India will also allow the Dalai Lama to visit the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, which China claims as part of its own territory and calls South Tibet. This represents a gradual but significant change in India’s Tibet policy, and it flows directly from China’s refusal to acknowledge India’s security concerns.

When Narendra Modi took office in 2014, his government hesitated to openly acknowledge official interactions with the Dalai Lama, ceding some ground to Chinese sensitivities. But by last month, President Pranab Mukherjee was hosting the Dalai Lama at a summit held in his official residence, the first meeting in decades between a serving Indian president and the Tibetan leader.

China reacted strongly to this meeting, saying New Delhi was disrespecting one of Beijing’s core interests. New Delhi retorted that the Dalai Lama was a revered spiritual leader and it was a nonpolitical event. China has also objected to the planned visit by the Dalai Lama to Arunachal Pradesh, saying it would damage bilateral ties.

Behind all this are broader strategic disagreements, including the “technical hold” placed by China on India’s attempt at the United Nations to designate Pakistan-based Jaish-e-Mohammad chief Masood Azhar as a terrorist. Beijing has blocked India’s move for nearly a year despite support from all other members of the 15-nation Security Council.

After India recently tested long-range ballistic missiles, China indicated it would be willing to help Pakistan increase the range of its nuclear missiles. When the Obama administration asserted that Beijing was an “outlier” in refusing to back India’s membership in the multinational Nuclear Suppliers Group, China replied that “membership shall not be some kind of farewell gift for countries to give to each other.” Meanwhile China is pursuing its $46 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor that traverses the disputed territory of Kashmir, implicitly acknowledging Pakistan’s claims there.

Still, India remains wary of upping the ante on the Tibet issue, which dates to the British Raj. The origins of the Sino-Indian war of 1962, in which India was defeated, can be traced to the asylum provided to the Dalai Lama after China’s annexation of Tibet. China’s repressive policies in the Tibet Autonomous Region have kept the Tibet question unresolved all these years. China portrays the Dalai Lama as a separatist “wolf in sheep’s clothing” and fumes at India for keeping him as an honored guest.

China has been relentless in seeking the Dalai Lama’s global isolation. After he visited predominantly Buddhist Mongolia in November, China closed a key border crossing with Mongolia and imposed new tariffs on commodity shipments. Mongolia, desperate to enhance economic ties in critical areas such as mining and infrastructure, apologized to Beijing and promised that the Dalai Lama would no longer be allowed to visit.

New Delhi seems to recognize that sacrificing the interests of the Tibetan people hasn’t yielded India any benefits, nor has there been tranquillity in the Himalayas for the past several decades. As early as 2010, New Delhi stopped referring to Tibet as part of China in joint statements with Beijing. As China’s aggressiveness grows, Indian leaders find themselves with fewer levers to affect Chinese behavior, so further supporting the legitimate rights of the Tibetan people could be an attempt to set new terms of engagement with Beijing.

This dovetails with the Modi government’s broader interest in promoting Buddhism as a means to cultivate ties with neighbors and express India’s ancient heritage. The prime minister himself has visited the Indian city of Bodh Gaya, the birthplace of Buddhism.

It remains to be seen how far the Modi government will go in challenging China on one of its core interests. But the recent evolution in India’s Tibet policy underscores that as China becomes stronger and more aggressive in pursuit of its interests, it should be ready for pushback from regional states that view its growing might with dread. Chinese hegemony will not come easy.

This commentary was published in Wall Street Journal

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.