[1] NSS 2017, “National Security Strategy of the United States of America”, White House – The Donald J. Trump administration, December 2017, accessed April 22, 2020 https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf

[2] Alyssa Ayres, “US Relations with India – Prepared statement by Alyssa Ayres – Before the Committee on Foreign Relations – Hearing on ‘US–India Relations: Balancing Progress and Managing Expectations’,” Council on Foreign Relations, May 24, 2015, accessed April 22, 2020, https://www.cfr.org/content/publications/attachments/052416_Ayres_Testimony.pdf

[3] Mike Pompeo, “Remarks by Secretary Pompeo at the India Ideas Summit & 44th Annual Meeting of USIBC”, US Embassy and Consulates in India, June 13, 2019, accessed April 29, 2020, https://in.usembassy.gov/remarks-by-secretary-pompeo-at-the-india-ideas-summit-44th-annual-meeting-of-u-s-india-business-council/

[4] Jeff Smith, “Modi 2.0: Navigating Differences and Consolidating Gains in India–U.S. Relations”, The Heritage Foundation, August 05, 2019, accessed April 28, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/modi-20-navigating-differences-and-consolidating-gains-india-us-relations

[5] USTR press release, “United States Will Terminate GSP Designation of India and Turkey”, The Office of the United States’ Trade Representative, March 04, 2019, accessed April 28, 2020, https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2019/march/united-states-will-terminate-gsp

[6] Neha Dasgupta & Aditya Kalra, “Exclusive: U.S. tells India it is mulling caps on H-1B visas to deter data rules – sources”, Reuters, June 19, 2019, accessed April 22, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trade-india-exclusive/exclusive-u-s-tells-india-it-is-mulling-caps-on-h-1b-visas-to-deter-data-rules-sources-idUSKCN1TK2LG

[7] Sriram Lakshman, “U.S. will consider ‘301 probe’ on India, says trade official”, The Hindu, July 12, 2019, accessed April 28, 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/us-will-consider-301-probe-on-india-says-trade-official/article28415242.ece

[8] USIBC press release, “USIBC Prepares Executive Defense Mission to DefExpo 2020”, US-India Business Council, January 29, 2020, accessed April 29, 2020, https://www.usibc.com/press-release/usibc-prepares-executive-defense-mission-to-defexpo-2020/

[9] The Hindu report, “India’s arms imports from U.S. up by 550%: report”, The Hindu, March 13, 2018, accessed April 29, 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/indias-arms-imports-from-us-up-by-550-report/article23166097.ece

[10] Sanjaya Baru, “An agreement that was called a deal”, The Hindu, July 21, 2015, accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/indiausa-stand-in-nuclear-deal/article7444348.ece

[11] SIPRI factsheet, “The Sipri Top 100 Arms‐Producing And Military Services Companies, 2018”, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, December 2019, accessed April 29, 2020, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/1912_fs_top_100_2018.pdf

[12] DSCA press release, “Fiscal Year 2016 Sales Total $33.6B”, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, November 08, 2016, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/news-media/news-archive/fiscal-year-2016-sales-total-336b

[13] DSCA press release, “Fiscal Year 2017 Sales Total $41.93B”, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, November 28, 2017, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/news-media/news-archive/fiscal-year-2017-sales-total-4193b

[14] DSCA press release, “Fiscal Year 2018 Sales Total $55.66 Billion”, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, October 09, 2018, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/news-media/news-archive/fiscal-year-2018-sales-total-5566-billion

[15] DSCA press release, “Fiscal Year 2019 Arms Sales Total of $55.4 Billion Shows Continued Strong Sales”, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, October 15, 2019, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/news-media/news-archive/fiscal-year-2019-arms-sales-total-554-billion-shows-continued-strong-sales

[16] Aaron Gregg, “Revolving door between Pentagon and defense contractors continues to spin”, Stars and Stripes, November 05, 2018, accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.stripes.com/news/us/revolving-door-between-pentagon-and-defense-contractors-continues-to-spin-1.555340

[17] NPR, “Investigation Finds Acting Defense Secretary Shanahan ‘Did Not Promote Boeing’”, NPR, April 25, 2019, accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2019/04/25/717158531/investigation-finds-acting-defense-secretary-shanahan-did-not-promote-boeing

[18] Joe Gould, “Trump advances ‘Buy American’ arms sales plans”, Defense News, July 16, 2018, accessed April 28, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/digital-show-dailies/farnborough/2018/07/16/trump-advances-buy-america-arms-sales-plans/

[19] Julian Borger, “Rex Tillerson: ‘America first’ means divorcing our policy from our values”, The Guardian, May 04, 2017, accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/may/03/rex-tillerson-america-first-speech-trump-policy

[20] Mike Stone & Matt Spetalnick, “Exclusive: Trump to call on Pentagon, diplomats to play bigger arms sales role – sources”, Reuters, January 08, 2018, accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-weapons/exclusive-trump-to-call-on-pentagon-diplomats-to-play-bigger-arms-sales-role-sources-idUSKBN1EX0WX

[21] DSCA news release, “Fiscal Year 2019 Arms Sales Total of $55.4 Billion Shows Continued Strong Sales”, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, October 15, 2019, accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/news-media/news-archive/fiscal-year-2019-arms-sales-total-554-billion-shows-continued-strong-sales

[22] Aaron Mehta, “The US brought in $192.3 billion from weapon sales last year, up 13 percent”, Defense News, November 08, 2018, accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/industry/2018/11/08/the-us-brought-in-1923-billion-from-weapon-sales-last-year-up-13-percent/

[23] Santanu Chaudhury, “India Approves $4.1 Billion Boeing Order”, The Wall Street Journal, June 06, 2011, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304432304576369183889074472

[24] Snehesh Alex Philip, “INS Arihant, Chinook, P-8I — game-changing Indian military inductions in the last decade”, The Print, December 29, 2019, accessed May 14, 2020, https://theprint.in/defence/ins-arihant-chinook-p-8i-game-changing-indian-military-inductions-in-the-last-decade/342022/

[25] Snehesh Alex Philip, “Army and IAF fought over Apache choppers, costing us Rs 2,500 crore more. Blame their silos”, The Print, February 28, 2020, accessed May 14, 2020, https://theprint.in/opinion/brahmastra/army-and-iaf-fought-over-apache-choppers-costing-us-rs-2500-crore-more-blame-their-silos/372553/

[26] Biswarup Gooptu, “India signs deal for Harpoon Block II missiles with US”, The Economic Times, September 02, 2010, accessed May 14, 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/india-signs-deal-for-harpoon-block-ii-missiles-with-us/articleshow/6477810.cms?from=mdr

[27] ET Bureau, “India signs pact with US to buy 10 C-17 airlifters”, The Economic Times, July 15, 2011, accessed May 14, 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/india-signs-pact-with-us-to-buy-10-c-17-airlifters/articleshow/8865467.cms?from=mdr

[28] TNN report, “India to buy US torpedoes for maritime patrol”, The Economic Times, June 29, 2011, accessed May 14, 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/india-to-buy-us-torpedoes-for-maritime-patrol/articleshow/9038318.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

[29] PTI report, “US accepts India’s request for supplying 6 more C-130J planes”, The Economic Times, July 20, 2012, accessed May 14, 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/us-accepts-indias-request-for-supplying-6-more-c-130j-planes/articleshow/15058063.cms

[30] PTI report, “India signs contract with US firm for 72,400 assault rifles”, The Economic Times, February 12, 2019, accessed May 14, 2020, https://m.economictimes.com/news/defence/india-signs-contract-with-us-firm-for-72400-assault-rifles/articleshow/67962476.cms

[31] Franz-Stefan Gady, “Upgraded Indian Attack Submarines to Receive US Anti-Ship Missiles”, The Diplomat, October 05, 2016, accessed May 14, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2016/10/upgraded-indian-attack-submarines-to-receive-us-anti-ship-missiles/

[32] Franz-Stefan Gady, “India Approves Procurement of 10 More P-8I Maritime Patrol Aircraft”, The Diplomat, June 26, 2019, accessed May 14, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2019/06/india-approves-procurement-of-10-more-p-8i-maritime-patrol-aircraft/

[33] Rahul Singh, “India set to sign $930-mn deal for 6 Apache attack helicopters”, The Hindustan Times, December 21, 2019, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-set-to-sign-930-mn-deal-for-6-apache-attack-helicopters/story-R9BPnHdYmyYnimvHzOa7uJ.html

[34] US Embassy factsheet, “U.S. – India Defense Relations Fact Sheet”, US Embassy and Consulates in India, December 09, 2016, accessed May 14, 2020, https://in.usembassy.gov/u-s-india-defense-relations-fact-sheet-december-8-2016/

[35] Bureau report, “India To Buy C-130J Super Hercules For $134 Million”, Defense World, August 19, 2016, accessed May 14, 2020.

[36] Kalyan Ray, “India seals $3 billion deal with USA to buy 24 helicopters for Navy, 6 for Army”, Deccan Herald, February 25, 2020, accessed May 14, 2020.

[37] Kalyan Ray, “India seals $3 billion deal with USA to buy 24 helicopters for Navy, 6 for Army”, Deccan Herald, February 25, 2020, accessed May 14, 2020.

[38] Cara Abercrombie, “Removing Barriers to U.S.-India Defense Trade”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 10, 2018, accessed April 30, 2020.

[39] Varghese K. George, Open Embrace: India-US Ties in the Age of Modi and Trump (New Delhi: Penguin Viking, 2018) p. 145

[40] State Dept. factsheet, “U.S. Security Cooperation With India”, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs — US State Department, June 04, 2019, accessed April 30, 2020.

[41] Lalit K Jha, “India third Asian nation to get STA-1 status from US”, LiveMint, August 04, 2018, accessed April 30, 2020.

[42] Masaya Kato, “Trump sees big arms sales as quick fix for Japan trade deficit”, Nikkei Asian Review, April 20, 2018, accessed April 30, 2020.

[43] Aaron Mehta, “With massive F-35 increase, Japan is now biggest international buyer”, Defense News, December 18, 2018, accessed April 30, 2020.

[44] Kashish Parpiani, “ORF Issue Brief 339 – Understanding India–US trade tensions beyond trade imbalances”, Observer Research Foundation, February 05, 2020, accessed April 30, 2020.

[45] Donald Trump, “Remarks by President Trump at a Namaste Trump Rally”, US Embassy and Consulates in India, February 25, 2020, accessed May 02, 2020.

[46] Harsh Pant & Kashish Parpiani, “A Trump India visit, in campaign mode”, The Hindu, February 20, 2020, accessed May 02, 2020.

[47] Jack Guy, “Russia now second-largest global arms producer, overtaking UK”, CNN, December 10, 2018, accessed May 02, 2020.

[48] HT report, “India was 2nd largest arms importer in 2015-19, Russia’s share of Indian arms market declined”, The Hindustan Times, March 09, 2020, accessed May 02, 2020.

[49] Zhenhua Lu, “China sells arms to more countries and is world’s biggest exporter of armed drones, says Swedish think tank SIPRI”, South China Morning Post, March 12, 2019, accessed May 02, 2020.

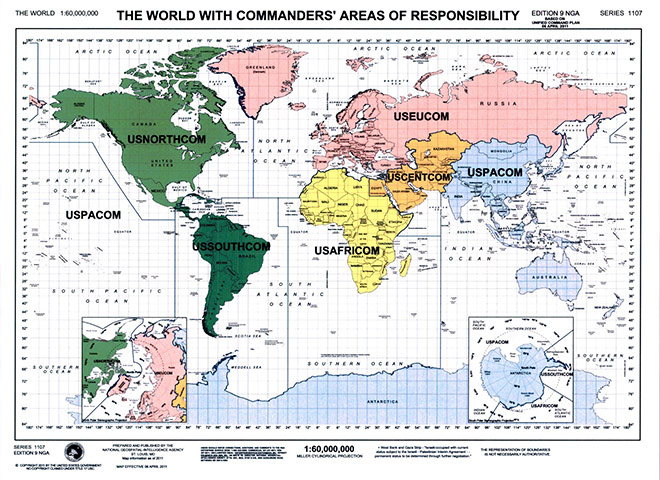

[50] Richard Weitz, “Pivot Out, Rebalance In”, The Diplomat, May 03, 2012, accessed May 02, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2012/05/pivot-out-rebalance-in/

[51] US INDOPACOM, “About US INDOPACOM”, The US Indo-Pacific Command, accessed May 02, 2020, https://www.pacom.mil/About-USINDOPACOM/

[52] Idrees Ali, “In symbolic nod to India, U.S. Pacific Command changes name”, Reuters, May 31, 2018, accessed May 02, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-defense-india/in-symbolic-nod-to-india-us-pacific-command-changes-name-idUSKCN1IV2Q2

[53] Prakash Karat, “Nationalism Made In USA”, Outlook India, January 29, 2018, accessed May 02, 2020, https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/nationalism-made-in-usa/299717

[54] Sriram Lakshman, “U.S. ends waiver for India on Iran oil”, The Hindu, April 22, 2019, accessed May 02, 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/us-ends-waiver-for-india-on-iran-oil/article26914949.ece

[55] PTI report, “India’s energy trade with US to jump 40% to $10 billion in FY20: Pradhan”, Business Standard, October 22, 2019, accessed May 03, 2020, https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/india-s-energy-trade-with-us-to-jump-40-to-10-bn-in-fy20-pradhan-119102100690_1.html

[56] Sandeep Unnithan, “Exclusive: We can match China in the Indian Ocean region, says Navy chief Sunil Lanba”, India Today, November 17, 2018, accessed May 03, 2020, https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/interview/story/20181126-we-can-match-china-in-the-indian-ocean-region-admiral-sunil-lanba-1388904-2018-11-17

[57] Prakash Karat, “Nationalism Made In USA”, Outlook India, January 29, 2018, accessed May 02, 2020, https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/nationalism-made-in-usa/299717

[58] Dinakar Peri, “Military Cooperation Group dialogue postponed”, The Hindu, March 08, 2020, accessed May 02, 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/military-cooperation-group-dialogue-postponed/article31016621.ece

[59] Yashwant Raj, “US to monitor end use of Pak F-16s, clears C-17 India deal”, The Hindustan Times, July 27, 2019, accessed May 03, 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/us-clears-670-million-arms-related-sales-to-support-india-s-c-17-aircraft-sop-for-pakistan/story-jBbdtJuaWfsncJcHTHwkSK.html

[60] ORF, “Coalitions and Consensus: In Defense of Values that Matter | Showstopper at Raisina Dialogue 2020”, Observer Research Foundation, January 18, 2020, accessed May 03, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gotKrQTVKQ4

[61] DSCA press release, “India – AGM-84L Harpoon Air-Launched Block II Missiles”, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, April 13, 2020, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/major-arms-sales/india-agm-84l-harpoon-air-launched-block-ii-missiles

[62] DSCA press release, “India – Integrated Air Defense Weapon System (IADWS) and Related Equipment and Support”, Defense Security Cooperation Agency,February 10, 2020, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/major-arms-sales/india-integrated-air-defense-weapon-system-iadws-and-related-equipment-and-support

[63] DSCA press release, “India – MK 54 Lightweight Torpedoes”, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, April 13, 2020, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/major-arms-sales/india-mk-54-lightweight-torpedoes-0

[64] DSCA press release, “India – MK 45 Gun System”, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, November 20, 2019, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/major-arms-sales/india-mk-45-gun-system

[65] DSCA press release, “India – 777 Large Aircraft Infrared Countermeasures Self-Protection Suit”, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, February 06, 2019, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/major-arms-sales/india-777-large-aircraft-infrared-countermeasures-self-protection-suite

[66] Huma Siddiqui, “Long wait over! Indian Armed forces to get high-tech US Armed Drones equipped with missiles”, The Financial Express, February 24, 2020, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.financialexpress.com/defence/long-wait-over-indian-armed-forces-to-get-high-tech-us-armed-drones-equipped-with-missiles/1877652/

[67] Abhishek Bhalla, “Defence Ministry gives clearance for procurement of military equipment worth Rs 22,800 crore”, India Today, November 28, 2019, accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/defence-ministry-gives-clearance-for-procurement-of-military-equipment-worth-rs-22-800-crore-1623487-2019-11-28

[68] Aman Thakkar, “U.S.-India Maritime Security Cooperation”, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, October 08, 2019, accessed May 03, 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/us-india-maritime-security-cooperation

[69] DoD archives, “Remarks by Secretary Panetta at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses in New Delhi, India”, The US Department of Defense, June 06, 2012, accessed May 03, 2020, https://archive.defense.gov/transcripts/transcript.aspx?transcriptid=5054

[70] Christopher K. Colley & Sumit Ganguly, “The Obama administration and India”, The United States in the Indo-Pacific — Obama’s legacy and the Trump transition (eds) Oliver Turner and Inderjeet Parmar, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), p. 56

[71] Amrita Nayak Dutta, “Why India wants to buy the MH-60 ‘Romeo’ helicopters from the US”, The Print, November 18, 2018, accessed May 03, 2020, https://theprint.in/defence/why-india-wants-to-buy-the-mh-60-romeo-helicopters-from-the-us/151140/

[72] DSCA press release, “India – AGM-84L Harpoon Air-Launched Block II Missiles”, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, April 13, 2020, accessed May 04, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/major-arms-sales/india-agm-84l-harpoon-air-launched-block-ii-missiles

[73] ANI report, “Came to know of Navy’s P-8I aircraft’s capabilities during Doklam episode: General Bipin Rawat”, The Economic Times, February 18, 2020, accessed May 04, 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/came-to-know-of-navys-p-8i-aircrafts-capabilities-during-doklam-episode-general-bipin-rawat/articleshow/74179809.cms

[74] DoD report, “Enhancing Defense and Security Cooperation with India – Joint Report to Congress”, The US Department of Defense, July 2017, accessed May 04, 2020, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/NDAA-India-Joint-Report-FY-July-2017.pdf

[75] Franz-Stefan Gady, “Upgraded Indian Attack Submarines to Receive US Anti-Ship Missiles”, The Diplomat, October 05, 2016, accessed May 04, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2016/10/upgraded-indian-attack-submarines-to-receive-us-anti-ship-missiles/

[76] Shiv Aroor, “Delighted With Fleet, Indian Navy Clears Decks For 6 More P-8Is”,LiveFist Defence, November 28, 2019, accessed May 04, 2020, https://www.livefistdefence.com/2019/11/delighted-with-fleet-indian-navy-clears-decks-for-6-more-p-8is.html

[77] Manu Pubby, “India may go for only naval UAVs from US”, The Economic Times, August 29, 2019, accessed May 04, 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/india-may-go-for-only-naval-uavs-from-us/articleshow/70882886.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

[78] Gayathri Iyer, “Sense for sensibility: Maritime domain awareness through the information fusion centre – Indian Ocean Region”, Observer Research Foundation, January 28, 2020, accessed May 08, 2020, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/sense-for-sensibility-maritime-domain-awareness-through-the-information-fusion-centre-indian-ocean-region-ifc-ior-60811/

[79] PIB press release, “Raksha Mantri Inaugurates Information Fusion Centre – Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR)”, Press Information Bureau, December 22, 2018, accessed May 08, 2020, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=186757

[80] PTI report, “Indian Navy forces Chinese naval ship to retreat from Andaman”, The Times of India, December 03, 2019, accessed May 08, 2020, timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/72352285.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

[81] ANI report, “Came to know of Navy’s P-8I aircraft’s capabilities during Doklam episode: General Bipin Rawat”, The Economic Times, February 18, 2020, accessed May 04, 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/came-to-know-of-navys-p-8i-aircrafts-capabilities-during-doklam-episode-general-bipin-rawat/articleshow/74179809.cms

[82] Pushan Das, “India’s defence procurement policy 2020: Old wine in a new bottle”, Observer Research Foundation, April 15, 2020, accessed May 04, 2020, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/indias-defence-procurement-policy-2020-old-wine-in-a-new-bottle-64673/

[83] DoD report, “Enhancing Defense and Security Cooperation with India – Joint Report to Congress”, The US Department of Defense, July 2017, accessed May 04, 2020, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/NDAA-India-Joint-Report-FY-July-2017.pdf

[84] ANI report, “Making in India: TLMAL delivers 100th C-130J Super Hercules empennage”, Business Standard, February 20, 2019, accessed May 07, 2020, https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ani/making-in-india-tlmal-delivers-100th-c-130j-super-hercules-empennage-119022000468_1.html

[85] Boeing India press release, “Tata Advanced Systems Delivers First CH-47 Chinook Crown and Tailcone for India to Boeing”, Boeing India, June 08, 2017, accessed May 07, 2020, https://www.boeing.co.in/news-and-media-room/news-releases/2017/june/tasl-delivers-first-ch-47-chinook-crown-and-tailcone.page?

[86] Manish Kumar Jha, “Committed To Create An Aerospace Ecosystem In India: Leanne Caret, President & CEO, Boeing Defence Space & Security”, Business World, August 09, 2019, accessed May 07, 2020, http://www.businessworld.in/article/Committed-To-Create-An-Aerospace-Ecosystem-In-India-Leanne-Caret-President-CEO-Boeing-Defence-Space-Security/09-08-2019-174586/

[87] Manu Pubby, “Boeing given time till 2020 to show offsets work on naval jet”, The Economic Times, November 30, 2018, accessed May 07, 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/boeing-given-time-till-2020-to-show-offsets-work-on-naval-jet/articleshow/66874523.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

[88] Vivek Raghuvanshi, “India’s audit agency questions $2.13B deal with Boeing”, Defense News, August 09, 2018, accessed May 07, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/industry/2018/08/09/indias-audit-agency-questions-213b-deal-with-boeing/

[89] Franz-Stefan Gady, “India Approves Procurement of 10 More P-8I Maritime Patrol Aircraft”, The Diplomat, June 26, 2019, accessed May 07, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2019/06/india-approves-procurement-of-10-more-p-8i-maritime-patrol-aircraft/

[90] Kashish Parpiani, “US export of Mahanian thought and India’s alignments in the Indian Ocean”, Observer Research Foundation, December 09, 2019, accessed May 07, 2020, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/us-export-of-mahanian-thought-and-indias-alignments-in-the-indian-ocean-58552/

[91] Franz-Stefan Gady, “Russia Offers India Three Refurbished Kilo-Class Submarines”, The Diplomat, April 03, 2020, accessed May 07, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/russia-offers-india-three-refurbished-kilo-class-submarines/

[92] Sushant Singh, “Washington lets Delhi know: Buy our F-16s, can give Russia deal waiver”, The Indian Express, October 20, 2018, accessed May 07, 2020, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/washington-lets-delhi-know-buy-our-f-16s-can-give-russia-deal-waiver-5409894/

[93] ANI report, “India concerned over ‘very high price’ of American missile shield for Delhi”, ANI News, February 16, 2020, accessed May 07, 2020, https://www.aninews.in/news/national/general-news/india-concerned-over-very-high-price-of-american-missile-shield-for-delhi20200216154517/

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV