Introduction

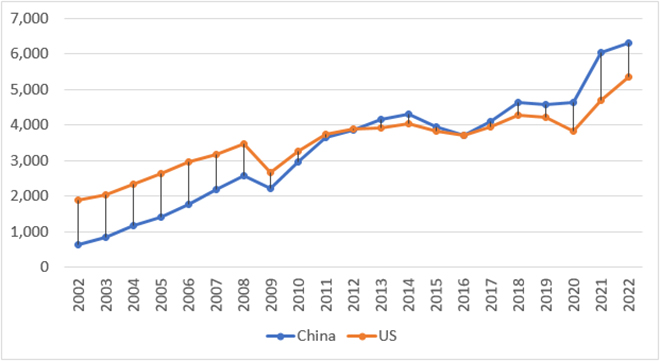

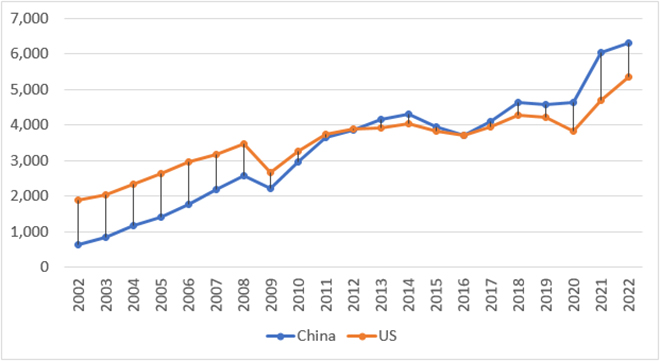

Geopolitics is intrinsically linked to geoeconomics, and neither exists in isolation. China is a fitting contemporary example of this nexus. In the 20th century, China held little geopolitical clout, if at all; it was a secondary player in a bipolar world led by the United States and the Soviet Union. Things began to change in the 21st century, and in 2002, China outperformed France to enter the top five largest merchandise traders in the world (along with the United States, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom).[1] In 2004, China’s total trade exceeded US$1 trillion for the first time in its history, while the US’s global trade stood at US$2.3 trillion in the same year. By 2013, China would overtake the US to became the world’s largest trader, and it has held the spot ever since; the gap between both economies’ total trade widened during the Covid-19 pandemic, from only 8.5 percent in 2019 to 21.2 percent in 2020, ballooning further to 28.7 percent in 2021.[2]

China swiftly transferred this increasing geoeconomic clout to the geopolitical arena, and began practicing what some analysts call ‘wolf warrior diplomacy.’ Academic Victor Cha’s essay in Foreign Affairs asserts that “China has weaponised economic interdependence” and its “acts of economic hostility are beyond the remit of the [World Trade Organisation].”[3] Such assertiveness in geopolitics is only possible because of China’s increasing economic influence. Today, three-fourths of the world conduct bigger volumes of trade with China than they do with the US.[4]

Figure 1. China’s and the US’s Total Global Trade (in US$ billion)

Source: International Trade Centre, “Trade Map”[5]

In the same vein, if India is to take its place in global geopolitics, it must first accumulate geoeconomic clout. India cannot follow China’s path by becoming the world’s factory, nor can it match its Asian neighbour in merchandise exports. In 2022, India’s annual trade exceeded US$1 trillion for the first time—a full 18 years after China crossed the mark. The Indian economy tilts far more towards services and the country remains a lightweight in global merchandise trade. In 2021, India was 18th in the list of the world’s largest exporters, below much smaller nations like Singapore and the United Arab Emirates. India, however, imports far more than it exports. In 2021, India was the world’s 10th largest importer. With a trade deficit of US$269 billion, India’s imports were approximately 60-percent more than its exports in 2022.[6] This deficit is usually portrayed in a negative light—i.e., a large deficit means that India must spend more foreign currency to import its goods, and be more economically dependent on other countries.

Yet, one specific portion of India’s import basket may be used to the country’s advantage and could potentially be used as a geopolitical tool—energy. Petroleum crude oil remains the single most traded commodity globally over the past five years.[7] India is the third largest importer of energy globally, after only China and the United States, and has a petroleum refining capacity of 5 million barrels per day (bpd), equal to those of the United Kingdom, Italy, Turkey and France combined.[8] In the geopolitical arena, India can use its position as a massive oil importer to its advantage. It appears that the wheels are already in motion.

India’s Oil Diplomacy with Moscow and Washington

Over the past few years, India has used economic diplomacy to position itself favourably in the geopolitics of oil. New Delhi’s delicate balancing of its political relationship with Washington DC, and with Moscow, has already been dissected in the media, but India’s economic manoeuvring in global oil politics has so far been overlooked by most analysts. This is most apparent in two distinct datapoints: India is the second largest importer of Russian crude (since March 2022), and was the largest importer of US crude oil (in 2021).

How exactly did India manage to become such an important market for US and Russian crude?

Russia

Remarkably, despite the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the near-global condemnation of Moscow’s aggression, oil has begun to flow in large volumes from Russia to India. This is a new development—between 2010 and 2020, Russia supplied only 0.5 percent of India’s oil imports.[9] In a world where any association with Moscow is repudiated, Western powers like the US and Germany would have normally been quick to condemn India. Instead, they have done the opposite and publicly acquiesced to India’s increasing imports of Russian oil. Germany’s Ambassador to India, Dr Philipp Ackermann noted in a February 2023 interview that “India buying oil from Russia is none of our business.”[10] Even US officials have gone on the record to say they are “comfortable with the approach India has taken” with regards to purchases of Russian crude, adding that its relationship with India is one of its “most consequential.”[11] New Delhi’s position remains clear: oil is an essential commodity in short supply in India, and the country will continue to source it from exporters that offer the best terms and prices. After all, Indians pay 20 percent more for oil at the pump than Americans,[12] whose per capita income is 30 times higher. Russian crude flowing to India comes at a considerable discount and can help minimise India’s budget deficit.[13]

Contrary to the narrative portrayed in the media, India’s imports of crude oil from Russia are motivated by economics, not politics. Despite Western sanctions on Russia and a price cap imposed by the G7 countries to limit the global purchase of Russian oil below a certain price limit, India’s imports of Russian oil have increased considerably in 2022 and 2023, to the benefit of the country’s exchequer. In 2022, India paid an average of US$91 per barrel of oil from Russia, much less than the average of US$97.5 per barrel for India’s total oil imports.[14] Despite the extra freight costs of bringing Russian crude to Indian shores, oil imports from Russia cost even less than what Indian importers paid in 2022 to lift oil from Saudi Arabia at US$103 per barrel, and from the United Arab Emirates at US$105 per barrel.

India has successfully played this situation to its advantage by continuing to court the West and the Quad on strategic issues. This, while increasing oil purchases from Russia, which faces so many Western sanctions that it has earned the moniker ”the most sanctioned country in the world.”[15]

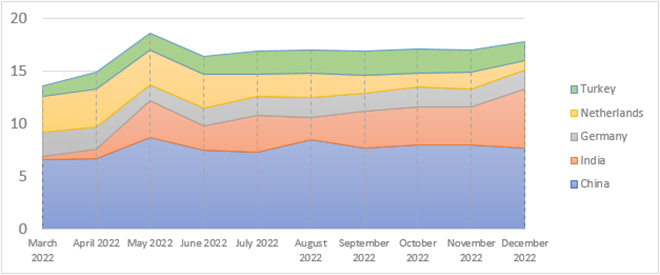

Russia has become the largest supplier of petroleum crude to India, for six months in a row from September 2022 to February 2023.[16] This was not an easy task: India’s oil companies have had to overcome numerous obstacles to do business with Russia. Russian insurance firms have gradually replaced Western insurance companies in the oil trade; due to financial restrictions on transactions with Russian firms in US$, trade now also takes place in Rupees, Rubles and Dirhams; finally, steep discounts from Russia offset the risk of doing business. Today, India is Russia’s second largest oil export destination, after only China. As a result of these exports, India-Russia trade has reached an all-time high of US$39 billion in 2022, more than three times the bilateral trade of US$11.5 billion in 2021.

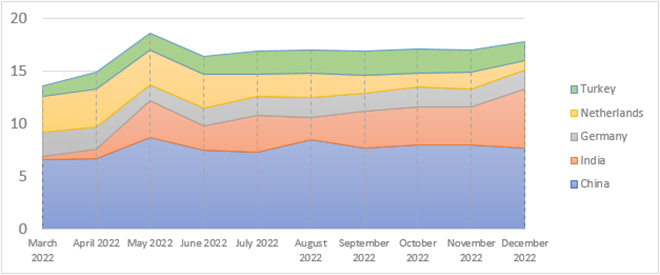

Figure 2: Russia’s Top 5 Oil Export Sources Since the Invasion of Ukraine (in million tonnes)

Source: 2023 Russia Fossil Tracker, Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air[17]

United States

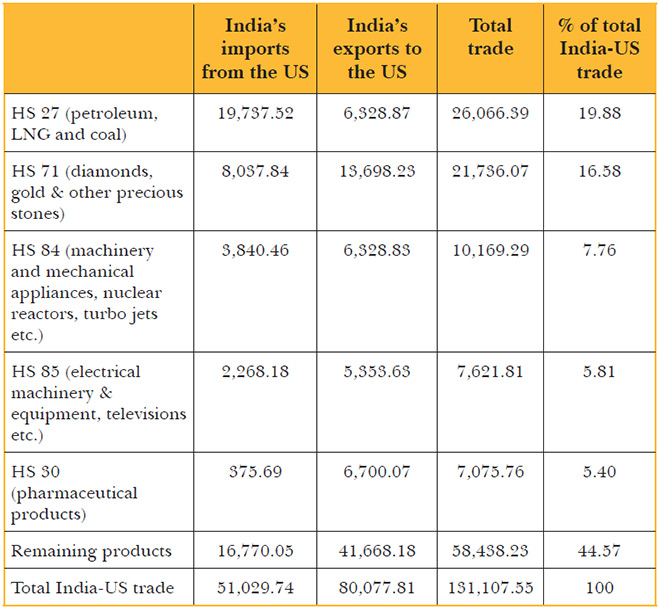

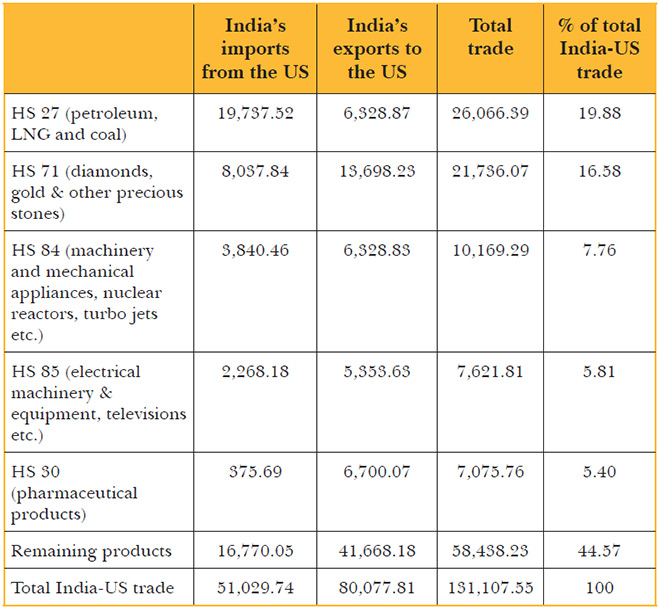

The story of Russian oil flowing to India generated enough interest, but the same cannot be said of India’s increasing salience as a market for US crude oil. Yet, the story of India’s energy trade with the US is of near-equal importance. The US is the world’s largest producer of oil and gas, and the country is arguably India’s most important strategic partner today. The India-US relationship is characterised by depth and diversity, and is constantly evolving. Like most bilateral relationships, it rests on an economic foundation of trade and investment. Since 2021, oil and gas has become the largest component of India-US trade—this includes India’s imports of crude petroleum oil, finished petroleum products and petroleum gas, as well as India’s exports of refined petroleum (see Table 1).

How did petroleum become the largest component of India-US trade? The story is complex and one that traverses multiple geographies.[18]

India’s Stakes

India’s crude oil import basket has historically favoured suppliers from West Asia. The region’s numerous wars and political instability in the 1990s and the 2000s, and the Arab Spring in the 2010s, forced India to look elsewhere for more stable suppliers. In the 2010s, India began to source as much as 40 percent of its oil from other regions, primarily Latin America and Africa—Venezuela alone accounted for 12 percent of India’s oil imports in 2013.[19] However, since 2019, three changes prompted Indian oil majors to change their import strategy. First, the US stopped granting sanction waivers to importers of Iranian oil, threatening secondary sanctions on companies that continued importing from Iran. Indian oil importers promptly stopped buying from Iran. Second, the US sanctioned Venezuela’s national oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). By late 2020, Indian importers ceased all imports from PDVSA. Finally, Mexico, which used to be amongst India’s top 10 sources of oil imports, suddenly reduced its oil exports to India in 2021 in a bid to focus more on domestic supply and refining.

In a span of just two years, India completely ceased its oil purchases from Iran and Venezuela, and considerably reduced imports from Mexico. To make up for this large shortfall, India’s oil companies switched to US crude, which provided a mix of heavy oil (similar to Venezuelan and Mexican oil) as well as lighter oil grades (similar to Iranian crude). After all, US suppliers of crude were also perceived to be more reliable. As a result, the US went from being the 10th largest supplier of oil to India in 2018 to fifth largest in 2022. In addition to crude oil, India also imports petroleum gases, specifically liquefied natural gas (LNG), from the US; these imports amounted to US$2.1 billion in 2021 and US$1.8 billion 2022. The US is currently India’s 5th largest import source for LNG.

For the US

The US lifted its 40-year ban on the export of crude oil only in December 2015—until then, all production was reserved for domestic use. Once exports began, most US crude oil exports were destined for China, the world’s largest oil importer. Soon after, as a consequence of the US-China trade war, China imposed tariffs on US crude and LNG in 2019. The US retaliated by imposing bans on investments in Chinese energy enterprises like Sinochem and China National Offshore Oil Corporation. Not unexpectedly, US oil suppliers turned their eyes to the next largest oil importer in the world—India. In 2021, approximately 14 percent of US crude oil exports totaling US$9.5 billion were destined for India, making it the largest export market for US oil.

In 2022, US suppliers turned their attention to Europe, which was keen on weaning itself off Russian oil. Still, US crude exports to India increased in 2022 to US$10.1 billion. As long as the US-China trade war festers, India is likely to benefit as one of the largest buyers of US oil. Another element of the India-US energy trade is US imports of refined petroleum from India, including gasoline. Indeed, India was the 5th largest supplier of refined petroleum to the US in 2021, totaling US$3.2 billion, which increased to US$3.7 billion in 2022.

Table 1: Top 5 Products in India-US Trade in 2022 (2-digit HS code, in US$ billions)

Source: Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Government of India[20]

India Tweaks its Energy Security Calculus

For most of the 21st century, India’s oil imports were determined mostly by commercial calculations. This has changed over the past five years, and today, India’s oil imports are intrinsically linked to geopolitics. Consequently, oil has become a card that India can play on the table of geopolitics.

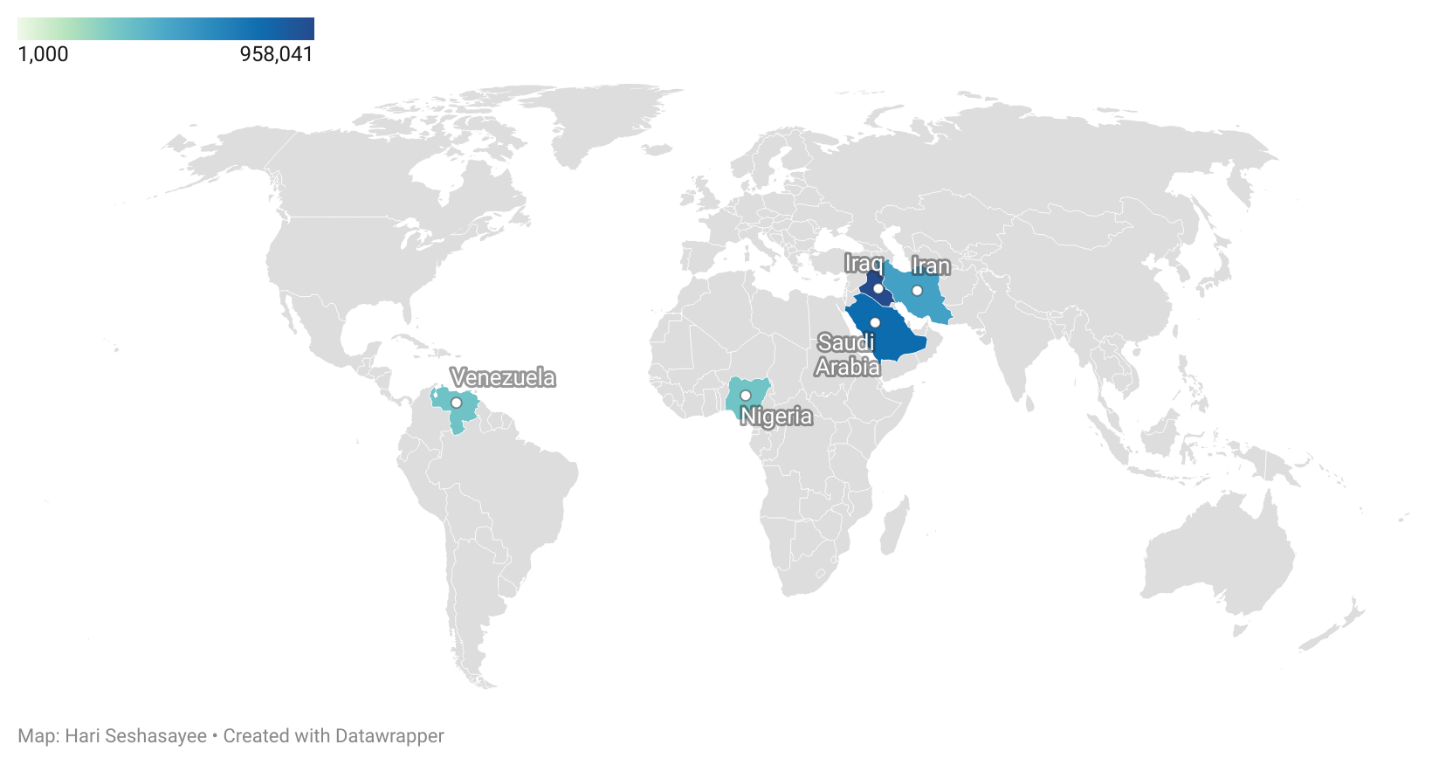

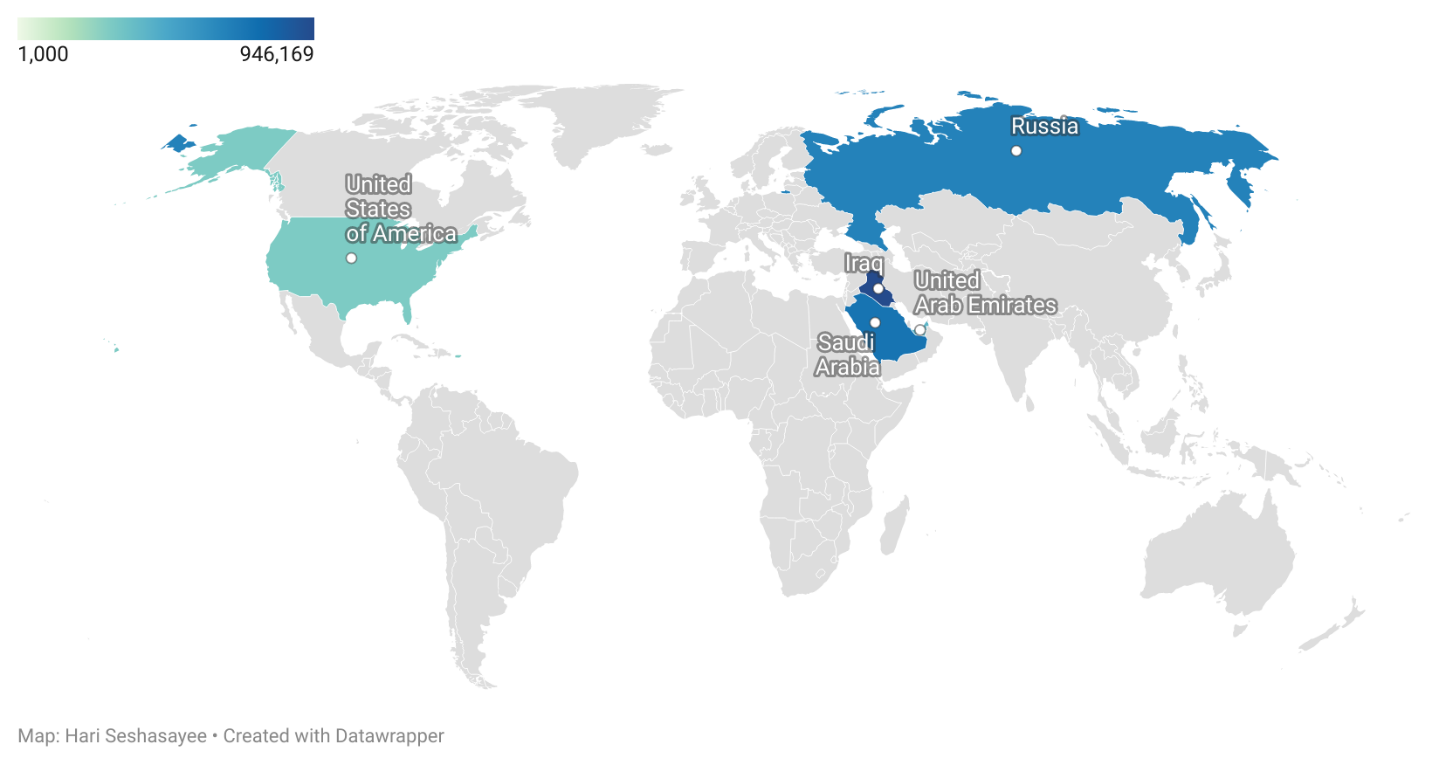

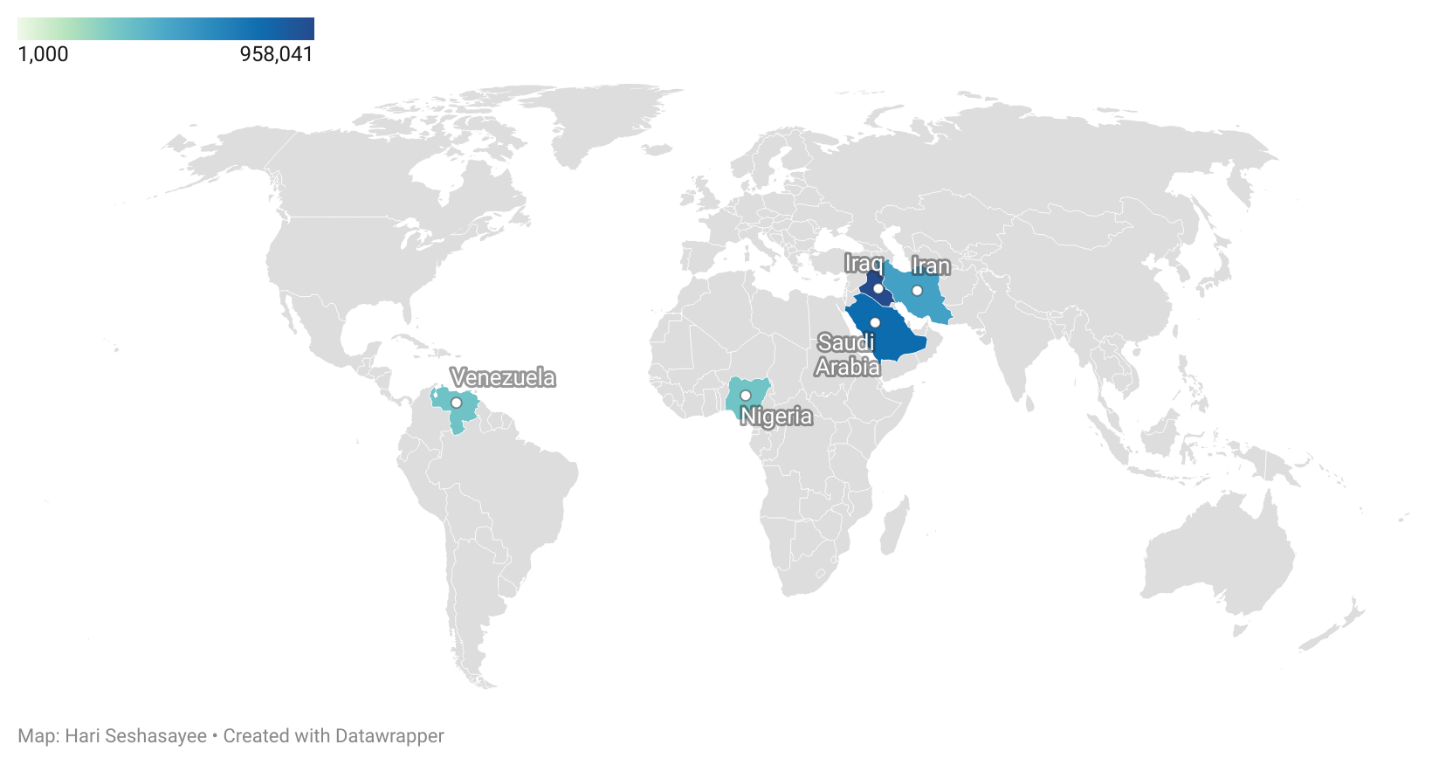

As recently as 2018, India’s top five oil import sources were Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Venezuela and Nigeria. This was a result of simple economics—i.e., buy oil from the cheapest sources, and diversify the import basket to include different regions. However, two of the top five—Iran and Venezuela—soon faced tough US secondary sanctions; it would simply not be worth the risk to continue importing oil from both countries.

Map 1: India’s Top 5 Sources of Oil Imports in 2018 (in bpd)

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India[21]

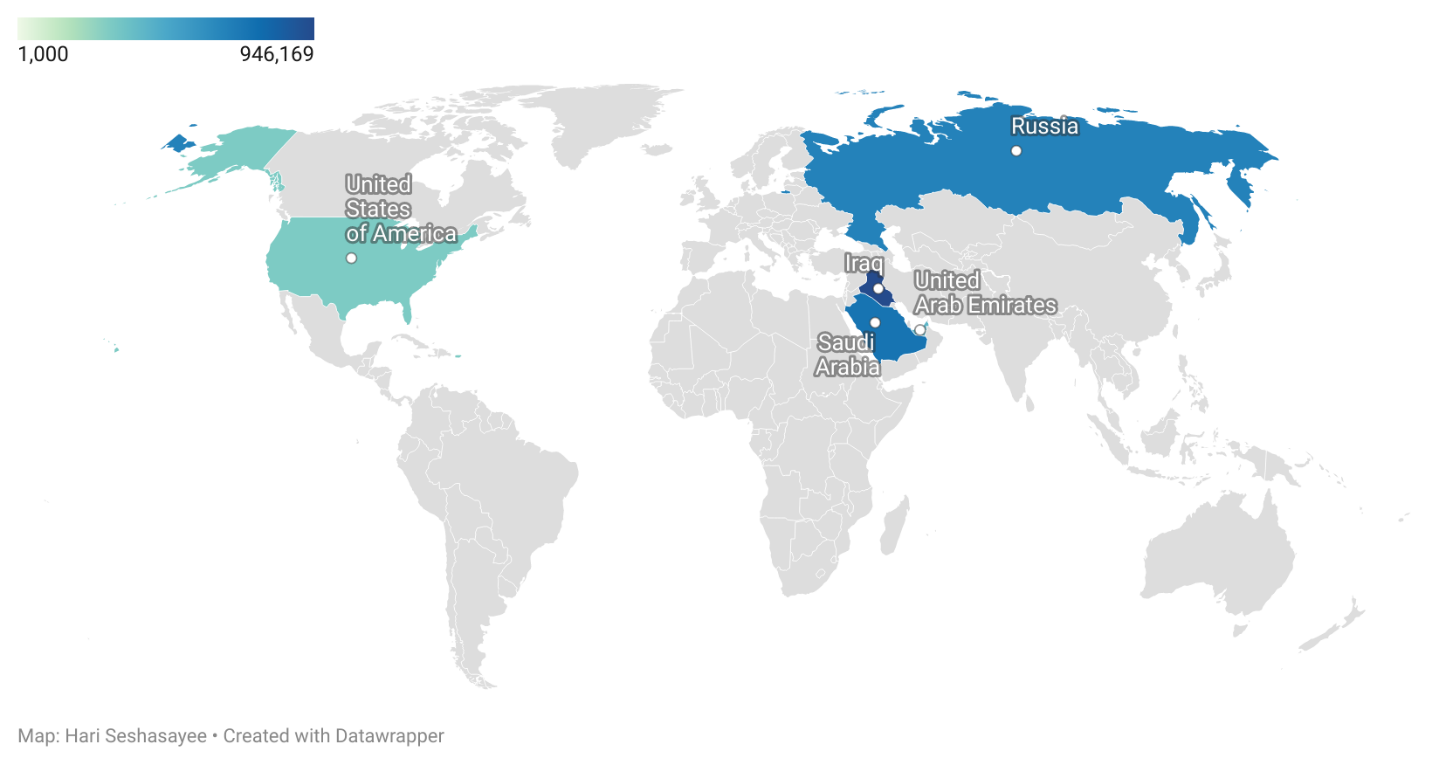

By 2022, India’s top five sources of oil imports changed considerably. While the top two from 2018—Iraq and Saudi Arabia—remain in their places, there are three new entrants: Russia is third, with imports at 664,855 bpd. More importantly, India is now Russia’s second largest oil export destination, which gives New Delhi more bargaining power. At fourth place is the United Arab Emirates, an increasingly strategic partner for New Delhi with which it signed a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement in 2022. In fifth place is the US, which managed to send large volumes of oil to India despite ramping up its exports to Europe, in order to replace Russian oil in that continent.

Map 2: India’s Top 5 Sources of Oil Imports in 2022 (in bpd)

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India[22]

This deepening of India’s energy relationship with both the US and Russia must be viewed within the context of two crucial changes in global energy markets. Both developments may prove to be advantageous to India’s place in the geopolitics of oil.

First is the West’s isolation of Russia, a global energy superpower that accounts for about 11 percent of global oil exports.[23] This portends a massive break in the energy relationship between Russia and Europe, which was once one of the most symbiotic in the world. Although some oil still makes its way from Russia to Europe by land through the Druzhba pipeline, the European Union has banned the seaborne import of Russian oil. This leaves Russia with a massive shortfall and a need for new partners. Three countries—China, India and Turkey—have stepped up their oil imports from Russia practically overnight to meet this shortfall. India benefits greatly from this new equation, as it finds itself in a buyer’s market with regards to Russian oil—one where Indian buyers can dictate terms, given the sparse market and numerous obstacles that must be overcome to import Russian oil.

Second is the looming era of decarbonisation. There is a global effort towards decarbonisation and reducing fossil fuel consumption. The targets set through the Paris Agreement and at the United Nations Climate Change Conferences are commendable, but the action on the ground has been slow. Some countries have fared better than others. In China, for instance, renewable energy capacity has already overtaken coal power capacity, and renewables now account for 47.3 percent of total installed generation, more than the 43.8 percent for coal in the country.[24] In the US, meanwhile, clean energy production has become cheaper than coal.[25]

Unfortunately, India has made less progress on this front, and coal and petroleum remain the mainstay of India’s energy basket. In the medium term, this could position India as an even more important importer of petroleum, and the country could potentially earn the dubious tag of the world’s largest importer of crude petroleum oil by 2040. If the trends do not reverse, India would then overtake China, which is increasingly turning towards renewable energy, and the US which already has copious petroleum reserves and is gradually reducing its petroleum imports.

The entry of geopolitical heavyweights, the US and Russia, into the top five of India’s oil import sources has long-term consequences. These are discussed in turn in the following paragraphs.

Oil as a tool of economic diplomacy

Oil is now an additional arrow in India’s quiver. Both Russia and the US will want to keep India on their side and would not want to risk losing the country as an oil export market. Nor would either of them risk more disruptions in global energy markets that would endanger their own economies. After all, the sheer size of India’s oil imports eclipses most other markets, with the sole exception of China. The more Russia depends on India as an oil export market, the easier it becomes for New Delhi to balance its interests between Russia and the West.

Changes in India’s energy basket

India’s oil import sources are becoming increasingly diversified, with suppliers from West Asia, Latin America, North America, Africa and now Russia added to the mix. Russia and the US will remain long-term providers of oil to India. As long as US sanctions on Iran and Venezuela persist, India will continue importing large quantities of US crude. Russia has all but lost Europe as an oil export market. Less than a handful of countries remain keen on importing Russian oil, so Moscow cannot afford to isolate India, its second largest export market. Even as West Asia continues to be India’s primary source of oil imports, Latin American and Africa suppliers will also be keen on increasing their share of exports to India. Since 12 percent of global growth in oil consumption is estimated to come from India in 2023,[26] oil exporters will be looking even more attentively at India.

The Global Energy Landscape

After the dip in energy consumption during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, both fossil fuels and renewables have seen an uptick in 2022. The year 2022 was when Western oil companies “made more money than in any year in the history of the industry.”[27] Yet, in March 2021, the director general of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) exclaimed that global oil demand may have reached its peak in 2019 and that natural gas would also peak by 2025. This may not seem surprising coming from IRENA, an inter-governmental agency mandated to promote the production of renewable energy.[28] Then in January 2023, BP, one of the world’s oldest and largest oil companies, estimated that global oil demand could indeed peak in the 2020s.[29] Others followed with a similar prognosis, including the International Energy Agency and a number of think tanks.

There seems to be growing consensus that peak oil is either already upon the world, or will come about in this decade. This has tremendous consequences for the global effort to combat climate change and reduce carbon dioxide emissions. The recent disruptions in the global energy sector and the fear of further risks are driving a faster shift to renewable energy which are, most often, a domestic resource. The Economist estimates that “the crunch caused by the war in Ukraine may, in fact, have fast-tracked the transition by an astonishing five to ten years.”[30] They add that “as green power is boosted and fossil-fuel use sags, the global economy is now expected to belch out much less carbon dioxide than had been predicted just 12 months ago. Artem Abramov of Rystad says emissions from fossil-fuel use, which he had predicted would be stable until the late 2020s, or even the 2030s, are now set to slide from 2025.”[31]

India should take heed of these global developments. Renewables may have already become cheaper than coal in the US and China, but that is far from the case in India. In 2022, India’s imports of petroleum and coal reached a record US$264 billion, which is a large 37 percent of the country’s total import bill[32] and 3.5 times larger than India’s entire defence budget of US$72.6 billion for 2023-24.[33] Given that the large majority of India’s oil and coal imports are done by government-owned companies, this has a direct impact on the country’s budget deficit and foreign exchange spending, so much that these imports singlehandedly determine the size of the country’s budget and trade deficits.

India must pivot away from fossil fuels and towards domestic sources of energy, and do so quickly if the country is to achieve energy independence by 2047, as outlined by the prime minister in India’s 75th Independence Day speech. The government’s National Policy on Biofuels and the Ethanol Blended Petrol Programme, which aims to reach a target of 20 percent of blending of ethanol in petrol, are welcome steps. So is the drive to incentivise green hydrogen production. The Government of India set an ambitious target of achieving 50 percent cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030; currently, India has an installed capacity of 175 GW of renewable energies like solar, wind, hydro and biomass, accounting for 42.5 percent of installed capacity.[34] Green hydrogen, which still remains at its nascent stages, could provide an extra push to the renewable energy sector, but it remains unlikely to have an impact before 2030. As Vikram Singh Mehta of the Centre for Social and Economic Progress notes, “The hard reality is that the Indian economy is built on fossil fuels. The transition to a new non-fossil fuel energy system will require massive investment and it will take decades. Until then, India will remain dependent on coal, oil and gas.”[35]

Conclusion

As India moves closer to becoming the world’s largest crude petroleum importer, New Delhi should use oil diplomacy to leverage its position in geopolitics. It must continue its delicate balance between the West and Russia. Along with its position as one of the world’s largest arms importers, oil may be one of the strongest cards in the deck for India in the global high table of geopolitics.

New Delhi should use this opportunity wisely, and maintain its strategic autonomy. Unfortunately, however, since India is likely to achieve its net-zero emissions target only by 2070, fossil fuels will continue to be a driver of India’s economy. Until then, India should take advantage of its moment in the geopolitics of oil.

Hari Seshasayee is a Visiting Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF). He has previously advised ProColombia, part of the Government of Colombia, and was a Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Endnotes

[1] “Trade Map,” International Trade Centre.

[2] “Trade Map,” International Trade Centre.

[3] Victor Cha, “How to Stop Chinese Coercion,” Foreign Affairs, January/February 2023.

[4] “Joe Biden is determined that China should not displace America,” The Economist, July 17, 2021.

[5] International Trade Centre, “Trade Map”.

[6] “Trade Map,” International Trade Centre.

[7] Calculations are based on data from 2017 through 2021, on 4-digit HS codes. Source: “Trade Map,” International Trade Centre.

[8] “BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2022,” BP, June 2022.

[9] “Trade Map,” International Trade Centre.

[10] News Desk, “‘If You Get it at Low Price…’ Germany Says India Buying Oil from Russia ‘Not Our Business’,” News18, February 22, 2023.

[11] ET Online, “US not looking to sanction India over Russian crude purchases as relationship is "most consequential",” Economic Times, February 09, 2023.

[12] Dorothy Neufeld, “Mapped: Global Energy Prices, by Country in 2022,” Visual Capitalist, December 3, 2022.

[13] A large percentage of India’s oil imports are done by public, government-owned companies, practically all of which are paid for in foreign currencies, primarily in USD.

[14] Calculations based on data from India’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry and conversions from tons to barrels are based on calculations from CME Group.

[15] Amit Chaturvedi, “These Are The World's Most-Sanctioned Countries. Russia Now No. 1,” NDTV, March 8, 2022.

[16] Sources: Ministry of Commerce and Industry for September 2022 to January 2023; for February 2023, see PTI, “India's Russian oil imports hit record high in February; now more than Iraq, Saudi put together,” The Hindu, March 5, 2023.

[17] “2023 Russia Fossil Tracker,” Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA).

[18] Hari Seshasayee, “Oil: A New Chapter in U.S.-India Relations,” The Wilson Center, February 10, 2022.

[19] “Trade Map,” International Trade Centre.

[20] Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Government of India.

[21] Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, https://tradestat.commerce.gov.in/meidb/Default.asp

[22] Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, https://tradestat.commerce.gov.in/meidb/Default.asp

[23] “Trade Map,” International Trade Centre, https://www.trademap.org/

[24] Zhao Xuan and Ward Zhou, “China’s Renewable Energy Capacity Overtakes Coal for First Time,” Caixin Global, February 15, 2023, https://www.caixinglobal.com/2023-02-15/chinas-renewable-energy-capacity-overtakes-coal-for-first-time-101998296.html

[25] Jeff St. John, “Clean energy is cheaper than coal across the whole US, study finds,” Canary Media, January 31, 2023, https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/fossil-fuels/clean-energy-is-cheaper-than-coal-across-the-whole-us-study-finds

[26] Calculations are based on data from the World Bank (https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/oil-prices-remain-volatile-amid-demand-pessimism-and-constrained-supply). Total growth in global oil consumption is estimated at 1.7% in 2023, out of which India accounts for 0.2%. India’s share is thus 12% of total global growth for 2023.

[27] Tom Wilson and Derek Brower, “What Big Oil’s bumper profits mean for the energy transition,” Financial Times, February 11, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/16f8800b-7300-42e0-a3c7-3400ed6c4fa5

[28] Dania Saadi, “World oil demand may have peaked in 2019 amid energy transition: IRENA,” S&P Global, March 16, 2021, https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/electric-power/031621-world-oil-demand-may-have-peaked-in-2019-amid-energy-transition-irena

[29] Tom Wilson, “BP cuts long-term forecast for oil and gas demand,” Financial Times, January 30, 2023 https://www.ft.com/content/857dfefa-98c6-4ed5-a0ad-5a7bb6669411

[30] “War and subsidies have turbocharged the green transition,” The Economist, February 13, 2023, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/02/13/war-and-subsidies-have-turbocharged-the-green-transition

[31] “War and subsidies have turbocharged the green transition,” The Economist, February 13, 2023, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/02/13/war-and-subsidies-have-turbocharged-the-green-transition

[32] Data from Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, https://tradestat.commerce.gov.in/meidb/Default.asp

[33] Manoj Kumar, “India raises defence budget to $72.6 bln amid tensions with China,” Reuters, February 1, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-raises-defence-budget-726-bln-amid-tensions-with-china-2023-02-01/

[34] “Power Sector at a Glance ALL INDIA,” Ministry of Power Govt. of India, accessed March 12, 2023, https://powermin.gov.in/en/content/power-sector-glance-all-india

[35] “28th Lalit Doshi Memorial Lecture by CSEP Chairman and Distinguished Fellow Vikram Singh Mehta,” Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP), 15 December 2022, https://csep.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Lalit-Doshi-Memorial-Lecture-by-CSEP-Chairman-1.pdf

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV