-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Nivedita Kapoor, “India-Russia Ties in a Changing World Order: In Pursuit of a ‘Special Strategic Partnership’”, ORF Occasional Paper No. 218, October 2019, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

India and Russia shared decades of close linkages at the highest levels during the Soviet era. The tumult of the immediate post-Soviet years, however, reverberated through the Indo-Russia relationship as well, as the newly established Russian Federation sought to rebuild its foreign policy. The years immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union saw the Boris Yeltsin administration adopting a pro-Western foreign policy orientation. For India, meanwhile, it was the time it began liberalising its economy and looking to the West for trade and investment. Both countries, therefore, were occupied with domestic priorities while adjusting to a changed world order with the United States (US) as the sole superpower.

Even so, India and Russia both made efforts to revive their relationship. In 1993 they signed a Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, and a year later they followed it up with a Military-Technical Cooperation agreement. India would eventually become a leading importer of Russian weapons, following a brief period from 1990-93 when there was a sharp fall in the volume of arms sales.[1] By the mid-1990s, Russia’s exports to India and China were contributing 41 percent of the total revenue of its defence industry.[2] This was crucial for the survival of Russia’s arms industry, which suffered as its own military reduced orders in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Indeed, as early as 1992, India and Russia had negotiated arms agreements worth $650 million.[3] A particularly high point since then has been the evolution from “a purely buyer-seller relationship to joint research, design development and production of state of the art military platforms,”[4] a successful example of it being Brahmos missile. The two are also involved in indigenous production of tanks and fighter jets, along with the upgrade of existing systems.

However, there has been no parallel revival in economic relations. In the 1990s, disputes regarding rupee-rouble rate and repayment of amount owed by India continued.[5] The Russian economy’s downslide, alongside competition from other fast-developing nations, as well as the opacity of laws in the post-Soviet state, all contributed to the decline in the share of India in Russian trade. By 1996, Russia’s trade with India contributed a mere one percent of Russia’s overall trade.[6]

The cultural and people-to-people contacts that had flourished during the Soviet Union period—bolstered by significant funding and scholarships for regular exchange—also dropped. The number of institutions in India teaching Russian language declined, as well as the number of students enrolled in these courses.[7]

A renewed effort to strengthen the bilateral relationship was made at the beginning of the presidency of Vladimir Putin in 2000, when the annual summits between India and Russia were instituted. In 2010, marking a decade of the ‘Declaration on Strategic Partnership’ between the two countries, the joint statement proclaimed that the relationship had reached “the level of a special and privileged strategic partnership.”[8]

The process of re-establishing the multi-dimensional relationship has been long; it has also had to contend with the geo-political and geo-economic shifts[9] both at the regional and global levels. This has required the two countries to overcome the old romanticism of the Indo-Soviet ties and engage at a pragmatic level.[10] Today there is no denying the mutual trust and friendship that exists between the two countries. However, the divergences in the goals of the two nations have sharpened in recent times – fuelled by both bilateral and international factors – and have the potential to deeply impact the future of Indo-Russia relationship. These factors were brought under renewed focus during the first five years of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government.

India-Russia Relations, 2014-18: Key Aspects

In 2014, India saw a change of government with Narendra Modi of the BJP taking over as prime minister. For Russia, it was a year when its focus was firmly on the domestic situation after the Ukrainian crisis and annexation of Crimea,[a] and the resulting deterioration of ties with the West. Both these events would influence the foreign policy trajectories of the two governments in the coming years, albeit in different ways. For Russia, this led to a growing dependence[11] on China both economically and strategically. India, responding to a rising power in its backyard, had already been moving towards building closer ties with the US, which had introduced its own pivot to Asia. This focus was carried forward by the newly-elected Modi government, witnessed in a steady rise in economic and defence ties between India and the US. India also strengthened its relations with Japan, West Asia and the immediate neighbourhood in the five-year period.

In a nutshell, PM Modi’s foreign policy has been marked by whirlwind visits across the globe[12] aimed at revitalising ties with a host of countries. This sense of exuberance, however, was missing in the country’s relations with Russia in the years immediately following Modi’s assumption to the prime ministership. To be sure, this is not to say that the drift in the partnership began in 2014. Even without the inertia of the second UPA term (2009-14), there were already signs of stagnating relations for some time. It only became more pronounced during Modi’s first term, due to a combination of domestic and global factors.

At the systemic level, the period 2014-18 saw a continuation of the changes underway in the global order, with the decline of US primacy and the rise of other emerging powers, particularly China. This has led to an attempt by these powers to shore up their influence, especially in Asia – reflected in China advancing its Belt and Road Initiative (or BRI, which India opposed),[13] the enunciation of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ (opposed by Russia[14] and China[15]) and Russia’s aim of a “greater Eurasian partnership.”[16]

Political

Political relations between India and Russia have historically been steady and cordial. The two countries have had the advantage of what analysts refer to as a “problem-free environment”[17] despite a weak economic base. A total of 19 annual summits have been held uninterrupted, alternately in India and Russia, since they were first instituted in 2000. The leaders of the two countries also meet regularly at the meetings—or on the side-lines—of various multilateral organisations like the grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and G20. Indeed, it was Russia that pushed for India’s entry into SCO; India became a full member in 2017. A major reason for this was Moscow’s desire to prevent the organisation from being dominated by China,[18] a concern that was shared by the Central Asian states as well. China, while initially resistant to the idea, agreed on the condition that Pakistan too joined the multilateral body.[19]

The two sides also signed the ‘Strategic Vision for Strengthening Cooperation in Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy’ in 2014 and agreed on the ‘Partnership for Global Peace and Stability’ in 2016. In early 2019, Russia bestowed the Order of St Andrew the Apostle on PM Modi for his “distinguished contribution to the development of a privileged strategic partnership between Russia and India and friendly ties between the Russian and Indian peoples.”[20]

Apart from the annual summits, the defence ministers of the two countries get the chance to meet regularly as they co-chair the Inter-Governmental Commission on Military Technical Cooperation (IRIGC-MTC). These annual meetings seek to review defence cooperation between the two countries. India’s external affairs minister is the co-chair of the Inter-Governmental Commission on Trade, Economic, Scientific, Technological and Cultural Cooperation (IRIGC-TEC), while the Russian side is represented by the deputy prime minister. Other ministerial level meetings also take place annually, ensuring regular contacts at different levels of the government between the two countries.

Economic

The 2014 joint statement issued by India and Russia—meant to provide a vision for the coming decade for their relationship—identified the areas of energy, technology and innovation and economic cooperation as focal points. Some of the recommendations included participating in oil, gas, petrochemical and power projects in each other’s countries, joint design and development of technology in areas like space, defence, aviation, IT, new materials as well as an increased focus on high-technology sectors – while declaring that they will “facilitate the full realization” of “enormous untapped potential in bilateral trade, investment and economic cooperation.”

That year, India was 18th in the list of Russia’s top exporters while its ranking in the latter’s imports was at 23rd.[21] While this was an improvement from 2005, the trade relationship clearly needed an overhaul, with bilateral trade having reached a mere $9.51 billion in 2014 which was nowhere near the goal of $20 billion by 2015. The Druzbha-Dosti 2014 joint statement then set the target of attaining the trade level of $30 billion by 2025.

The balance of trade remains in favour of Russia and the deficit has risen two times in the last decade to reach $3.1 billion in 2014.[22] Russia mainly exports pearls and precious stones, machines, electronic equipment, fertilisers, photo and technical apparatus to India. Meanwhile, Indian exports consist of pharmaceuticals, electrical equipment, coffee, tea, apparels and pearls and precious stones.

The energy sector saw a certain degree of forward movement in 2015, with an MoU signed regarding exploration and production of hydrocarbons in Russia. Important agreements in the field of nuclear energy were finalised during 2014 and 2015: the construction of at least 12 nuclear power plants over the next two decades; “localization of manufacturing” for nuclear power plants; and supply of crude oil and helicopter engineering. In 2016, several deals in the hydrocarbon sector were also signed, the most important of which were a 23.9-percent stake in Vankorneft by Oil India Limited, OVL acquiring 11 percent more in Vankor oilfield and Rosneft buying a 49-percent stake in Essar Oil. The Rosneft acquisition of Essar at $12.9 billion was the largest FDI in India in the sector. It was also Russia’s largest outbound deal.[23] For India, Russia is the largest oil and gas investment destination, with a total of $15 billion in cumulative investments. In 2016, Indian companies spent $5.4 billion in acquiring oil and gas assets in Russia.[24] Russia was also added as a new source for long-term LNG imports and the first cargo of Russian LNG reached India at Dahej, Gujarat in June 2018.

The bilateral trade saw a decline for the second year in a row, despite the directive of the 2014 statement that called for realising the potential of the economic ties.

Table 1. INDIA-RUSSIA BILATERAL TRADE (2010-17)

| YEAR | BILATERAL TRADE ($ BILLION) |

| 2010 | 8.5 |

| 2011 | 8.9 |

| 2012 | 11.04 |

| 2013 | 10 |

| 2014 | 9.51 |

| 2015 | 7.83 |

| 2016 | 7.71 |

| 2017 | 10.17 |

Source: Ministry of External Affairs, Indian embassy in Moscow[25][26][27]

Table 1 shows the slow growth in the bilateral trade, which has hovered between $7-10 billion for almost a decade now. The contrast has been especially significant since both the countries have witnessed an increase in economic cooperation with other states but have failed to replicate the same with each other. In 2016, as a trade partner, India stood at 17th position in Russia’s list while Russia stood at 26th. A report of the India-Russia joint study group noted that in 2005-06, India constituted a mere 1.1 percent of the total Russian trade on average.[28] A decade since then, that figure still stood at 1.2 percent while the corresponding figure for Russia also stands at just one percent.[29]

Table 2a. RUSSIA’S TOP 5 TRADE PARTNERS (2018)

| COUNTRY | BILATERAL TRADE ($ BILLION) |

| China | 108.3 |

| Germany | 59.6 |

| Netherlands | 47.2 |

| Belarus | 34 |

| Italy | 27 |

Source: RT.com[30]

Table 2b. INDIA’S TOP 5 TRADE PARTNERS (2017-18)

| COUNTRY | BILATERAL TRADE ($ BILLION) |

| China | 89.7 |

| USA | 74.5 |

| UAE | 49.9 |

| Saudi Arabia | 27.5 |

| Hong Kong | 25.4 |

Source: Department of Commerce, Government of India[31]

There are several factors that have contributed to this weakness in India and Russia’s economic ties: lack of involvement of the private sector; absence of logistics; poor connectivity; and more recently, the stalling of the International North-South Economic Corridor, resulting in higher costs.[32] Russia’s main exports to the world consist of energy – oil, gas, nuclear – and arms sales. While the Indo-Russia energy sector has in recent years seen increased cooperation through two-way investment, difficulties involved in direct supply through pipelines remain present as ever. In a welcome development, the two-way investment target set at $30 billion by 2025 was met eight years ahead of schedule, in 2017. The new target has been reset to $50 billion by 2025.[33]

In another development, looking for alternative routes to deal with the logistics issue, India has indicated its intent to establish a shipping corridor from Chennai to Vladivostok, which would reduce the time for goods to be shipped to the Russian Far East by 16 days. However, it must be noted that this is still an initial proposal and a more concrete pitch for implementation on the ground is yet to be received from the Indian side. The idea finds more resonance when seen in the light of the Chinese Maritime Silk Route.

Defence

While India and Russia’s economic relationship has been a weak point in the post-Cold War period, the most glaring sign of the stagnation may yet be that in 2014, the US emerged as the top arms supplier to India, pushing Russia to the second position based on data for the preceding three years.[34] At the same time, India became the top foreign buyer of US weapons in 2014.[35] Given that the military-technical ties were historically the bedrock of India and Russia’s relationship, a drop in the sector was a clear matter of concern.

While in overall terms, Russia remained India’s top supplier of defence items during the period 2014-18, the total exports fell by 42 percent between 2014-18 and 2009-13.[36] Russia still commands 58 percent of total arms imports by India, followed by Israel and the US at 15 and 12 percent, respectively.[37] This figure, however, is a step down from 2010-14 when Russia had a share of 70 percent[38] of the Indian defence market.

Despite this, Russia’s market share ensures that the country remains a critical supplier to India, both of new arms and spare parts. The military-technical cooperation that includes transfer of technology and joint production is a unique relationship that is extremely valuable to India. Also, the low of 2014 has since been corrected and in 2016, crucial inter-government agreements were signed at the annual summit including the supply of S-400 Triumph Air Defence Missile System and four Admiral Grigorovich-class frigates[39] (the deals were finalised in 2018), as well as a shareholder deal regarding the manufacture of Ka-226T helicopters in India.

Table 3. INDIA-RUSSIA DEFENCE DEALS (2018-19)

| YEAR | DEAL | AMOUNT |

| 2018 | S-400 missile defence system | $5.2 billion |

| 2018 | Project 11356 class frigates (2) | $950 million |

| 2019 | Akula class nuclear-powered submarine | $3 billion |

| 2019 | T-90 tanks | $2 billion |

| 2019 | Igla-S Very Short-Range Air Defence Systems | $1.47 billion |

| 2019 | JV to manufacture of AK-203/103 rifles | $ 1 billion |

Source: Business Standard[40] Indian Defence Industries [41]

The first ever TriServices exercise under the annual INDRA format and joining of India as a full member of SCO were positive developments of 2017. Earlier, the format of INDRA was set as single-service exercises but this changed with the involvement of all three services – army, navy and air force. There were no significant arms deals signed in 2017.[42] This development came in the backdrop of the cancelled Multi-role Transport Aircraft[43] and India pulling out of the Fifth Generation Fighter Aircraft project[44] that had begun in 2007. The latter project, after 11 years, remained stonewalled on issues of cost-sharing and technology to be used; India then decided to drop it.

Several factors have been identified for the gradual decline in the orders of India from Russia: India’s desire to diversify its defence imports and therefore a heightened competition for Russia with other suppliers; and dissatisfaction in India with post-sales services and maintenance being offered by Russia.[45] Moreover, India has also had concerns in the past regarding supply and servicing of defence supplies. Some of these included a five-year delay in the delivery of aircraft carrier Admiral Gorshkov (later renamed INS Vikramaditya) as well as its cost escalation from $974 million to $2.35 billion. India was also displeased by the high cost and low quality of spare parts for weaponry imported from Russia in the past, as well as delays in the supply.[46]

Cultural

There are 20 educational institutions across Russia that teach Indian languages. Latest figures suggest that about 11,000 Indian students are studying in Russia, primarily in medical and technical courses.[47] The number of tourists from Russia to India has been on the rise, and in 2017 it was the eighth largest source of foreign arrivals to India.[48] In comparison, the number of Indian tourists to Russia, though having increased, still remains low.

Table 4. TOURIST EXCHANGE (2016-17)

| 2016 | 2017 | |

| Russian tourists to India | 2,27,749 | 2,78,904 |

| Indian tourists to Russia | 59,000 | 71,000 |

Source: India Tourism Statistics[49], Russia Tourism[50]

The Case for a Reset

In 2017, the 70th year since the establishment of diplomatic relations between India and Russia, PM Modi was invited as the Guest of Honour for the St Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF). Despite having released the 2014 joint statement as a vision document for the coming ten years, a mere three years later, the June 2017 St. Petersburg declaration was again titled ‘Vision for the 21st century.’ Several of the sectors recognised in the 2014 for enhanced cooperation were once again identified in the 2017 joint statement; however, “concrete initiatives…to make the bilateral institutional dialogue architecture more result-oriented and forward-looking”[51] were once again missing. Some agreements were signed during the annual summit in 2017, including on cultural exchanges, construction of the third stage of Kudankulam nuclear power plant and railways; precious stones ; academic exchanges; and investments.[52] Not one of them, however, were big-ticket announcements.

Energy and defence form the core of the bilateral relationship but are no longer enough on their own, necessitating a search for new areas to serve as “catalysts for expanded cooperation.”[53] As Dmitri Trenin, director of the Carnegie Moscow Center noted, the “pattern” of the relationship had failed to evolve in the changing global scenario and the ties had not been put on a “qualitatively new level.”[54] Still, both countries have repeatedly expressed their commitment to their ties. India’s former external affairs minister Sushma Swaraj visited Russia three times in a period of 11 months in 2017-18 in an attempt to shore up ties, especially in the economic domain.

The Sochi Informal Summit

In May 2018, it was announced that PM Modi will meet President Putin for an informal summit at Sochi, the first interaction in such format with the Russian leader. The announcement came just a month after the Wuhan informal summit between PM Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping. While the latter had followed the Doklam standoff in July-August 2017, with an aim to remove “misconceptions”[55] and seek areas of cooperation, no specific reason was given for the summit with Russia except for “further strengthening our Special and Privileged Strategic Partnership.”[56]

Coming only four months before the October 2018 annual summit between India and Russia, the Sochi summit was an acknowledgement of the need to bring about a change in the relationship. The intent was also reflected in the directive given by the two leaders to their officials to “prepare concrete outcomes for the forthcoming summit,”[57] noting the lack of such during past ones, apart from the energy and defence sector.

The change was reflected in the joint statement, titled ‘Enduring Partnership in a Changing World,’ that contained several concrete plans for the year: the “conclusion of the contract for supply of S400;” first meeting of India’s NITI Aayog and Russia’s Ministry of Economic Development; start of talks on a free trade agreement (FTA) between Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and India; launch of single-window service in Russia for Indian companies; launch of Russia Plus in India to help Russian companies invest in India; holding of the India-Russia Business Summit; setting up of the Far East Agency in Mumbai; signing of the India-Russia Economic Cooperation: The Way Forward (March 2018); and the beginning of LNG supply from Gazprom (contract with GAIL).[58] There were over 50 ministerial level visits to enhance the ties. Apart from the $5.2-billion S400 deal, the year also saw the finalisation of four frigates—two to be purchased from Russia ($950 million) while two will be made at Goa Shipyard Limited ($500 million).

The S400 deal, despite the threat of it attracting Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), was a sign of India’s desire to maintain its strategic autonomy as well as build on its strong defence relationship with Russia. It remains to be seen if the US actually imposes CAATSA on the missile defence deal and if that happens, how India would respond. Moscow also remains a crucial partner in transfer of technology to help indigenous manufacturing in the defence sector. Also, the future pace of defence ties will be affected by how effectively India is able to handle the US pressure, given the ongoing tensions between the two former Cold War rivals.

Some of the defence deals signed with Russia in 2019 include a $3-billion deal for a nuclear submarine to replace INS Chakra, the approval for purchase of 464 T-90 tanks for $2 billion, and the launch of the joint project to manufacture of AK-203/103 rifle in Amethi in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Further, under emergency procurement, the defence ministry has approved the purchase of $1.47 billion ‘Igla-S Very Short Range Air Defence Systems (VSHORAD)’ from Russia.[59]

There is also an attempt to shore up the bilateral economic relationship with PM Modi being invited as the main guest for the Eastern Economic Forum in 2019. The first India-Russia Strategic Economic Dialogue was held in November 2018 to find ways to improve economic ties. It must be noted that several mechanisms already exist at the bilateral level with regard to trade issues[b] but they are hardly effective even as they have been around for more than a decade. Therefore, it remains to be seen if the latest initiatives would lead to a qualitative change in economic ties with Russia or merely follow the older pattern of inertia.

The International Context

The Indo-Russia relationship faces increasing stress from the evolving international scenario characterised by the rise of China and the impact it has on the broader regional and global order. India and Russia have followed remarkably different policies in dealing with this phenomenon, most visibly in Asia. In 2012, President Putin had called India a “key strategic partner in the Asia-Pacific region,” which assumed significance in light of an Asia “where China is looming increasingly large,” leading the two to “revise their relationship.”[60] This was also the year when Moscow’s pivot to Asia was confirmed through the APEC summit, a concept in which India occupied an important position.

However, subsequent events have led to a deepening of Russia-China strategic partnership due to a commonality of interests in political, economic and strategic domains while a similar level of engagement with other countries of Asia has not been realised. India is by no means an exception to this broader Russian policy drawback in Asia. However, given that Russia has a long history of relations with India since its independence—unlike the case of East Asia where it was largely side-lined during the Cold War period –bilateral reasons are inadequate in explaining why the potential of the strategic partnership has not been realised. In this case, Sino-Russian relations have been an important factor.

Russian Sinologist Alexander Lukin argues that the Russian officials have accepted that “cooperation with the West cannot be fully restored” after 2014, leading to a “methodical and deeply rooted pivot to China.”[61] Apart from the bilateral trade which touched over $100 billion in 2018, Russia also needs Chinese investment to fund its development needs. The two also share a common opposition to US hegemony and a focus on sovereignty, territorial integrity, non-interference in internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit. The imposition of western sanctions after the Ukrainian crisis and annexation of Crimea meant Russia had to look for a “strong external partner,” leading to a “more ambitious pivot to China.”[62] On the ground, this meant sales of S400 air missile defence system and Su35 fighter jets (overturning a decades-old policy), which will directly “affect the balance of power in Taiwan”[63] as well as beginning of joint naval exercises (2015).

On the economic front, Russia overtook Saudi Arabia as the leading oil supplier to China at certain points in 2015-16, reducing the restrictions around Chinese investment in the energy and infrastructure projects, signing of the largest ever $400 billion gas deal, proposal to connect Eurasian Economic Union to the Belt and Road Initiative after initial Russian hesitation regarding the latter as well as increase in cooperation in Central Asia. The 2016 Foreign Policy Concept of Russia also describes the “common principled approaches” of the two countries as one of the key elements “of regional and global stability.”[64] Russia concluded that in the prevailing scenario, a burgeoning relationship with China would best suit its national interests. It also needs to be acknowledged that in comparison, India would be hard-pressed to extend similar support to Russia due to its own economic limitations and strategic goals.

Moreover, these developments in Sino-Russian relations happened at a time when India was decisively reaching out to the US, distancing itself from the “rhetoric of non-alignment” to lead to one of the “most intense bilateral engagement that New Delhi enjoys with any nation.”[65] India became a major defence partner of the US (2016), began the 2+2 dialogue (2018), and signed the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA, 2016) as well as the Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA, 2018). The idea of ‘Indo-Pacific’, too, had been gaining ground at this time, with the Indo-US joint statement of June 2017 officially including the nomenclature in the bilateral document. Meanwhile, the allegation of Russian interference into the 2016 US presidential elections caused further divide between the two. In other words, Russia has directed its policy so as to counter the US predominance, one that India has shown no interest in backing due to its desire to improve its economic status and further relations with all major powers.[66]

Indeed, India has ramped up its engagement with other major powers like Japan, Israel, Germany and France.[67] In the case of Japan, which was building its own idea of Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP), it has consisted of an increased focus on relationship with India. Fuelled by economic complementarities and concerns over a rising China, the two countries have taken important steps to build a ‘Special Strategic and Global Partnership.’ Japan in 2014 announced investments of 3.5 trillion yen ($33.6 billion) over a period of five years in infrastructure and energy, areas that are of particular importance to India for its economic goals. The two are also collaborating on various connectivity projects in Asia and Africa (Asia-Africa Growth Corridor) – finding synergies in India’s Act East policy and FOIP. These developments have taken place alongside regular meetings of foreign secretary level trilateral of Japan, Australia, India since 2015; the first ‘formal official level discussions’[68] under the Quad framework (2017) and the maiden meeting of leaders of Japan, America, India (JAI) in 2018 on the side-lines of G20 summit. Interestingly, the meeting of JAI was followed by the first trilateral summit of Russia, India, China (RIC) in 12 years – at the initiative of Moscow. But the trilateral (RIC), which meets regularly at the level of foreign ministers, has seen only “nominal”[69] levels of cooperation, hobbled as it is by differences between India and China. The three leaders are again expected to meet on the side-lines of the Osaka G20 summit in 2019.

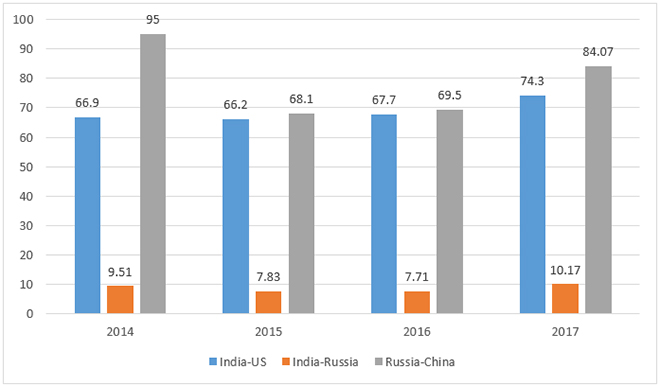

An increased focus on relations of India with the US, and of Russia with China, has also been reflected in a steady growth in the economic relationship. India-US trade in goods stood at $87.5 billion in 2018 and Russia-China trade had reached $107.06 billion[70] in the same year.

Figure 1: BILATERAL TRADE COMPARISON ($ BILLION)

This discussion highlights the different foreign policy trajectories that India and Russia have followed in the previous five years. If this status quo continues, it will only lead to widening divergences. This has been most prominently reflected in the Russian displeasure over the idea of the Indo-Pacific, with Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov calling it an “artificially imposed construct” being promoted by the US, Australia and Japan to contain China.[74] While India was not singled out by Lavrov in his remarks, it is clear that Moscow’s interpretation of the concept is different from that of New Delhi.

The remarks, made in February 2019, came despite the fact that several months earlier in June 2018, PM Modi in his Shangri La speech made it clear that the concept of Indo-Pacific for India is based on “inclusiveness, openness and ASEAN centrality and unity” and not “as a strategy or as a club of limited members.” Specifically mentioning Russia, the prime minister hailed it as a “measure of our strategic autonomy that India’s Strategic Partnership, with Russia, has matured to be special and privileged.” The prime minister also clarified that Indo-Pacific is not “directed against any country” and that India seeks to build through dialogue a common rules-based order in the region, “based on the consent of all, not on the power of the few.”[75] Former External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj in September 2018 had personally conveyed the same to Lavrov during their meeting.[76] It must be noted that Russia has been sceptical about the Indo-Pacific as enunciated by the US, favouring the description as ‘Asia-Pacific’ instead.

It is clear that while the two countries still regard each other as valued partners with a friendship built on “deep mutual trust,”[77] their foreign policy goals are taking them in different directions. Russia needs China for its national interests; India has its own policy aims. As New Delhi seeks to increase its influence in Indo-Pacific through its Act East policy, it needs partners in a region where Russia has a much weaker presence. Russia’s role in the Indo-Pacific will depend on how successful it is “in dealing with the fundamental problems hindering its economic development,”[78] making it only natural for India to look for partners that can help it achieve its goals in the region. The situation has also been complicated by their failure to find convergence on issues like multipolarity, the role of SCO, and the EAEU.[79]

Russia’s increased engagement with Pakistan has also not been received well in New Delhi. In 2014, Moscow removed the arms embargo imposed on Pakistan and sale of Mi-35 helicopters and engines for JF-17 Thunder went through. A gas pipeline between Lahore and Karachi was also funded by Moscow via a $2-billion loan. It has also been noted that the last direct mention of Pakistan in Indo-Russia joint statement was in 2010 and since then, Russian officials have at different times referred to India’s neighbour as being key in fighting terrorism.[80] The two sides also began joint military exercises—much to the dismay of India – especially in 2016 when it was reported by Russian state-run news agency TASS that the drills would be held in Gilgit-Baltistan, an area India considers as being illegally occupied by Pakistan.[81] The drills were finally held in Cherat after strong Indian protests even though Russia insisted it was always the only venue they considered.

To a certain extent, this was a message to India for its growing closeness to the US; at the same time, Moscow is looking at Pakistan with reference to its policy on Afghanistan and wider stability in Central Asia and Caucasus – where differences have now emerged with New Delhi. Zamir Kabulov, Russia’s special representative to Afghanistan, has gone on record to say that it would not be possible to eliminate terrorism “without the cooperation of Pakistan.”[82] India does not agree with Russia’s treatment of Pakistan as “part of the solution rather than part of the problem.”[83] Earlier, Russia was a supporter to the Northern Alliance, like India, but later “diversified contacts” to all “key Afghan communities.”[84] In recent times, since reports came out of the Islamic State (IS) marking its presence in Afghanistan, Russia has decided to also engage in discussions with the Taliban through the Moscow format of talks. In 2018, India participated in these talks –attended by Taliban representatives—at the ‘non-official level’ through the presence of two retired diplomats. India has never before participated in any capacity in peace talks with the Taliban even as others have done so, including the US.

Conclusion

India and Russia continue to share a common strategic rationale for their relationship: apart from bilateral synergies, the two are members of various multilateral organisations including BRICS, RIC, G20, East Asia Summit and SCO—where avenues for cooperation on issues of mutual importance exist. There is also a need for cooperation in areas like counterterrorism, cyber security, the Afghanistan conflict, outer space, and climate change. The fact that Russia holds a permanent seat at the UN Security Council and has been a supporter of India on various issues including Kashmir at the international forum is of critical importance for New Delhi.

India would do well to take steps to shore up its relations with Russia to prevent it from becoming more dependent than it already is on China. At the same time, Russia would also benefit from diversifying its relations across the region, including India, so as to prevent its pivot to Asia becoming a pivot to China. Russia has made it clear that it is not in an alliance relationship with China and wants to have a multi-vector foreign policy. It remains to be seen how Moscow plans to translate its policy pronouncement to reality. In its post-Cold War avatar, it has been in a particularly weak position in Asia and does itself no favours by becoming over-dependent on China – raising fears of becoming a junior partner in the relationship.

It is no secret that India would benefit from a closer cooperation with Russia in the Indo-Pacific. Russia’s deteriorating relations with the US make the prospects of such a move difficult, but the option of cooperating with India should be considered by the former superpower. In the May 2019 talks between US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and President Putin, the latter hoped the relationship would improve. While that might look like a tall order given the state of affairs, a stable, friendly US-Russia dynamic will benefit India as it would contribute to an increased convergence of world views. Here, the US policy can also play a role in case it decides to accommodate Russia in order to counter China, and the former superpower decides to take up the offer. In other words, an improvement of relations between the two former Cold War rivals would be a positive development for India.

The proposal of President Putin for a ‘more extensive Eurasian partnership involving the EAEU and China, India, Pakistan and Iran’ should be used by India to strengthen its presence in Eurasia. The main challenge here would be from China’s Belt and Road Initiative that covers a vast expanse of the region, which Russia has joined and plans to link the EAEU to it. India’s connectivity plans in the region, in the form of INSTC, have been languishing for a long time, constrained by problems of security issues along the corridor, ‘low economic viability and lack of financial investment,’ disputes between participant countries and other projects competing with it.[85] These issues, including the low level of container trade and streamlining of rules across countries, are yet to be addressed – despite the project having been conceived way back in 2002.

The taking over of operations at Chabahar port earlier this year has opened up India’s route to Afghanistan bypassing Pakistan and onwards to Iran and Central Asia. Given that Russia has been concerned about increasing Chinese influence in Central Asia, expanding its linkages via Chabahar and INSTC onwards to India can be considered by both countries. PM Modi at the Shangri La dialogue already noted that India was willing to ‘work with everyone’ to promote trade through connectivity. There will also need to be a push to accelerate negotiations on the creation of EAEU-India free trade zone.

India and Russia will have to diversify their areas of cooperation beyond energy and defence. The trade relationship remains weak and needs active intervention to take advantage of policies like ‘Make in India’. Also, concrete proposals in the areas already identified by the two countries need to be identified and implemented on a priority basis, including startups, infrastructure, shipbuilding, river-navigation, high speed railways, space, food processing, and high-technology products.[86] -.

India can also be of help to Russia in providing manpower for engaging in activities like agriculture, and construction[87] without engaging in permanent settlement. Given that the situation is particularly acute in the Russian Far East, which has a population of only six million and faces steady out-migration[88], India can provide a solution to the demographic problem apart from being a partner in investing in energy and other projects in the region. The two sides are already discussing this and the topic figured in the discussions between PM Modi and President Putin when they met on the side-lines of the SCO summit in June 2019. They noted that skilled Indian manpower can be used to develop the region.[89] An increase in bilateral cooperation between private sector companies of India and Russia, especially in new-age technologies can be a potential area of cooperation.

The micro, small and medium enterprises should also be encouraged to look at Russia to promote bilateral trade links. In order for business links to flourish, the prospect of issuing long-term business visas should also be considered by the two governments. The potential for collaboration with Japanese and South Korean partners to build trilateral partnerships in the RFE can be explored in the areas of mining, timber and pharmaceuticals.

India and Russia’s relationship cannot flourish on defence and historical linkages alone. With systemic changes underway in international relations, new dimensions of cooperation need to be found to build a strong economic and strategic partnership. Both India and Russia will have to learn to navigate their relationship amidst challenges emerging not just from bilateral factors but also regional and global ones, as both countries seek to strengthen their position at a time of flux in the international order.

Endnotes

[a] The Ukrainian crisis began in November 2013 when pro-Russia Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych abandoned a proposed trade deal with the European Union in order to establish closer cooperation with Russia. Following this, protests by Ukrainians gathered steam which later turned violent. In February 2014, Yanukovych disappeared, causing a power vacuum. By 27-28 February, main buildings in Crimean capital were seized by pro-Russia armed men. In early March, Russian parliament voted for authorizing use of its forces in Ukraine to protect interests of its citizens. Meanwhile, a referendum held in March 2014 in Crimea saw the majority Russian speaking peninsula vote to secede from Ukraine and join Russia.

[b] These mechanisms include the India – Russia Forum on Trade and Investment, India-Russia CEOs’ Council, India-Russia Business Council, India-Russia Trade, Investment and Technology Promotion Council, India- Russia Business Dialogue and India-Russia Chamber of Commerce.

[1] Sergey Kortunov,. “The influence of external factors on Russia’s arms export policy”, SIPRI, accessed May 25, 2019.

[2] Jerome Conley, “Indo-Russian Military and Nuclear Cooperation: Implications for U.S. Security Interests, INSS Occasional Paper no. 31 (February 2000): 11.

[3] Ian Anthony, “Economic dimensions of Soviet and Russian arms exports”, SIPRI, accessed May 25, 2019.

[4] Embassy of India, “India-Russia Defence Cooperation”, accessed May 30, 2019.

[5] Anita Singh, “India’s relations with Russia and Central Asia”, Royal Institute of International Affairs 71: 1 (January 1995):69-81.

[6] R.G. Gidadhubli, “Moving Towards Consolidation: India-Russia Trade Relations,” Economic and Political Weekly 33: 3 (January 1998), 91-92.

[7] Katherine Tsan, “Re-Energizing the Indian-Russian Relationship: Opportunities and Challenges for the 21st Century,” Jindal Journal of International Affairs 2:1 (August 2012), 140-184.

[8] Ministry of External Affairs, “Joint Statement: Celebrating a Decade of the India- Russian Federation Strategic Partnership and Looking Ahead”, accessed May 30, 2019.

[9] Meena Singh Roy, “The Trajectory of India-Russia Ties: High Expectations and Current Realities,” Indian Foreign Affairs Journal 11: 4 (December 2016), 322-331.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Alexander Gabuev, “Friends with Benefits? Russian-Chinese Relations after the Ukraine Crisis”, Carnegie Moscow Center, accessed July 2, 2019.

[12] Ashley Tellis, “Modi’s Three Foreign Policy Wins”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed July 10, 2019.

[13] Ministry of External Affairs, “Official Spokesperson’s response to a query on participation of India in OBOR/BRI Forum”, accessed October 19, 2019.

[14] Sergei Lavrov, “Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s Remarks and Answers to Media Questions During The Russia-Vietnam Conference of the Valdai Discussion Club”, accessed October 19, 2019.

[15] Xinhua, “China, ASEAN countries agree to forge closer ties”, accessed October 19, 2019.

[16] Kremlin, “Plenary session of St Petersburg International Economic Forum”, accessed October 19, 2019.

[17] Dmitri Trenin, “Pressing Need to Tap Potential of Bilateral Ties,” in the A New Era: India-Russia Ties in the 21st Century, (Moscow: Rossiyskaya Gazeta, 2015).

[18] Marc Lanteigne, “Russia, China and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization: Diverging Security Interests and the Crimea Effect,” in the Russia’s Turn to the East. Global Reordering, eds. Helge Blakkisrud and Elana Wilson Rowe (Palgrave Pivot, Cham, 2018), 119-138.

[19] Alexander Gabuev, “Shanghai Cooperation Organization at Crossroads”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed October 9, 2019.

[20] President of Russia, “Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi presented with Order of St Andrew the Apostle the First-Called”, The Kremlin, accessed June 20, 2019.

[21]Exim Bank of India, “Potential for Enhancing India’s Trade with Russia: A Brief Analysis”, Working Paper no. 42, accessed July 2, 2019.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Livemint, “Essar Oil, Rosneft say $13 billion sale completed”, accessed October 11, 2019.

[24] Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, “Annual Report 2019-19”, accessed October 9, 2019.

[25] Ministry of External Affairs, “India-Russia Relations, July 2013”, accessed October 9, 2019.

[26] Ministry of External Affairs, “India-Russia Relations, June 2015”, accessed October 9, 2019.

[27] Embassy of India Moscow, “Bilateral Relations: India-Russia Relations”, accessed October 9, 2019.

[28] “Report of the India-Russia Joint Study Group”, accessed 12 May, 2019.

[29] Russia Direct, “How to take Russia-India economic ties to the next level”, accessed 15 June, 2019.

[30] RT, “China tops list of Russia’s biggest trade partners”, accessed October 9, 2019.

[31] Department of Commerce, “Export Import Data Bank: Country – wise: Russia”, accessed October 9, 2019.

[32] See n. 28.

[33] PTI, “India attaches ‘highest importance’ to ties with Russia: Sushma Swaraj”, accessed July 2, 2019.

[34] Rajat Pandit, “US pips Russia as top arms supplier to India”, The Times of India, accessed 5 June, 2019.

[35] CNBC, “India becomes biggest foreign buyer of US weapons” accessed July 18, 2019.

[36] Pieter D. Wezeman, “Trends in International Arms Transfer 2018”, SIPRI, accessed June 18, 2019.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Pieter D. Wezeman and Siemon T. Wezeman, “Trends in International Arms Transfer 2014”, SIPRI, accessed June 8, 2019.

[39]PIB, “Signing of Military and Defence agreements”, accessed June 8, 2019.

[40]Ajai Shukla, “Russia, already India’s biggest arms supplier, in line for more”, Business Standard, accessed October 9, 2019.

[41] Indian Defense Industries, “Russia”, accessed October 9, 2019.

[42]Siemon T. Wezeman et al., “Developments in Arms Transfers, 2017,” in the SIPRI Yearbook. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[43]Franz-Stepan Gady, “India-Russia Aircraft Deal Terminated”, The Diplomat, accessed May 26, 2019.

[44]PTI, “India tells Russia to go ahead with FGFA project; says it may join at a later stage”, accessed June 13, 2019.

[45]Russia International Affairs Council and Vivekananda International Foundation, “70 th Anniversary of Russia-India Relations: New Horizons of Privileged Partnership”, RIAC, accessed July 2, 2019.

[46]Jyotsna Bakshi, “India-Russia Defence Co-operation,” Strategic Analysis 30: 2 ( April – June 2006): 449-466.

[47]Embassy of India, “Bilateral Relations: India-Russia Relations”, accessed June 15, 2019.

[48]Ministry of Tourism, “Indian Tourism Statistics at a Glance 2018”, accessed June 19, 2019.

[49]Ibid.

[50]Vikram Suhag, “China’s attractiveness as a tourist destination for the Russian traveler. Inferences India should draw”, Eurasian Studies, accessed October 9, 2019.

[51]PIB, “Joint Statement on the visit of President of the Russian Federation to India for 15th Annual India-Russia Summit”, accessed May 26, 2019.

[52]Ministry of External Affairs, “List of MOUs/Agreements signed during the 18th India-Russia Annual Summit”, accessed June 1, 2019.

[53]Andrei Zakharov, “Exploring New Drivers in India-Russia Cooperation,” ORF Occasional Paper 124 (October 2017): 1-34.

[54]Dmitri Trenin, “From Greater Europe to Greater Asia? The Sino-Russian Entente”, Carnegie Moscow Center, accessed May 24, 2019.

[55]PTI, “Modi-Xi summit in Wuhan removed several misconceptions between India and China: Indian envoy”, accessed July 2, 2019.

[56]Ministry of External Affairs, “Visit of Prime Minister to Russia”, accessed May 25, 2019.

[57]Ministry of External Affairs, “Informal Summit between India and Russia”, accessed May 17, 2019.

[58]PIB, “India-Russia: an Enduring Partnership in a Changing World”, accessed July 19, 2019.

[59]Dinakar Peri, “Army invokes emergency powers for missile deal”, The Hindu, accessed July 2, 2019.

[60]Harsh V. Pant, “India-Russia Ties and India’s Strategic Culture: Dominance of a Realist Worldview”, India Review 12:1(February 2013): 1-19.

[61] Alexander Lukin, Russia and China: The New Rapprochement, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018).

[62]Alexander Gabuev, “Friends with Benefits? Russian-Chinese Relations after the Ukraine Crisis”, Carnegie Moscow Center, accessed May 2, 2019.

[63]See n. 61; 157.

[64]The Embassy of the Russian Federation to the United Kingdom, “The Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation 2016”, Accessed July 19, 2019.

[65]Ashley Tellis, “Narendra Modi and US-India Relations,” in the New India: Transformation under Modi Government, (eds) Bibek Debroy et al., (New Delhi: Wisdom Tree, 2018).

[66]See n. 17.

[67]See n. 65.

[68]Ryosuke Hanada, “The Role of U.S.-Japan-Australia-India Cooperation, or the “Quad” in FOIP: A Policy Coordination Mechanism for a Rules-Based Order”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, accessed May 26, 2019.

[69]Bobo Lo, “New Order for Old Triangles? The Russia-China-India Matrix”, IFRI, accessed June 9, 2019.

[70]RT, “Russia’s trade with China surges to more than $107 billion”, Accessed June 23, 2019.

[71] Office of the United States Trade Representative, “India”, accessed October 9, 2019.

[72]James Dobbins, et al. “A Warming Trend in China-Russia Relations”, Accessed October 9, 2019.

[73]The Asan Forum, “Prospects and Limitations of Russo-Chinese Economic Relations”, accessed October 9, 2019.

[74]Sergei Lavrov, “Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s Remarks and Answers to Media Questions during the Russia-Vietnam Conference of the Valdai Discussion Club”, Valdai Discussion Club, accessed July 12, 2019.

[75]Ministry of External Affairs, “Prime Minister’s Keynote Address at Shangri La Dialogue”, accessed June 19, 2019.

[76]PTI, “Engagement in Indo-Pacific not directed at any country: India to Russia”, Accessed June 1, 2019.

[77]See n. 64.

[78]See n. 17.

[79]Ashley Tellis, “Troubles Aplenty: Foreign Policy Challenges for the Next Indian Government”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed June 1, 2019.

[80]Nirmala Joshi and Raj Kumar Sharma, “India-Russia Relations in a Changing Eurasian Perspective”, India Quarterly, 73: 1 (January 2017): 36-52.

[81]Nidhi Razdan, “Russia Says Military Drill With Pakistan Not In Pak-Occupied Kashmir”, Accessed June 19, 2019.

[82]Devirupa Mitra, “Pakistan Critical to Defeating ISIS, Says Russian Special Rep to Afghanistan”, The Wire, accessed July 8, 2019.

[83]See n. 80.

[84]Ekaterina Stepanova, “Russia’s Afghan Policy in the Regional And Russia-West Contexts”, IFRI, accessed June 14, 2019.

[85] Meena Singh Roy, “Strategic Contours of Connectivity between India and Russia,” in the A New Era: India-Russia Ties in the 21st Century, (Moscow: Rossiyskaya Gazeta, 2015).

[86]Ministry of External Affairs, “Saint Petersburg Declaration by the Russian Federation and the Republic of India: A vision for the 21st century”, Accessed July 8, 2019.

[87]Nandan Unnikrishnan and Uma Purushothaman, “Russian Far East & opportunities for India”, Observer Research Foundation, accessed October 9, 2019.

[88]Kazuhiro Kumo, “Demographic Situation and Its Perspectives in the Russian Far East: A Case of Chukotka”, RRC Working Paper series, accessed October 19, 2019.

[89]Ministry of External Affairs, “Transcript of Media Briefing by Foreign Secretary on the bilateral meeting between India and Russia on the sidelines of SCO Summit 2019 in Bishkek”, accessed July 15, 2019.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Nivedita Kapoor is a Post-doctoral Fellow at the International Laboratory on World Order Studies and the New Regionalism Faculty of World Economy and International Affairs ...

Read More +