Introduction

The new India-France Indo-Pacific Roadmap released in July 2023 during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Paris marked an interesting development. The fifth paragraph outlines a shared commitment between the two nations to strengthen “plurilateral arrangements with Australia and the UAE and build new ones in the region”.[1] This statement signifies several noteworthy evolutions in how India and France engage at the regional level. By referencing the cooperation frameworks established between the two countries in recent years, it provides tangible evidence of the intentions articulated in the Joint Strategic Vision of India-France Cooperation in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) in 2018[2] to associate “other strategic partners in the growing cooperation between India and France, as and when required and (...) establish trilateral dialogues”.[3] By using the term ‘plurilateralism’ instead of simply referring to trilateral dialogues, it injects a more political and more conceptual dimension into initiatives that had previously been described primarily by their nature. In essence, by broadening the scope of their bilateral cooperation from the IOR to encompass the entire Indo-Pacific region, the Roadmap underscores the importance of moving beyond the traditional self-centred approach to foster a more outward-looking dynamic with key regional partners. The cooperative mechanisms established by India and France recently—India-France-Australia (IFA) in 2020 and India-France-UAE (IFU) in 2023—represent initial steps in this direction.

Definitional implications

The use of the term ‘plurilateral arrangements’ in this context is rooted in India’s approach to international cooperation around the concept of plurilateralism, which is often considered to be inherited from its non-alignment stance. Interestingly, ‘plurilateral arrangements’ is not a term that is frequently found in the French strategic lexicon, except for the occasional usage within the European context to describe certain types of agreements and projects.[4] In such cases, ‘plurilaterals’ often refer to agreements involving a limited number of stakeholders and occupying an intermediate space between bilateral and multilateral arrangements;[5] therefore, the term ‘plurilateral’ is used interchangeably with ‘minilateral’. In the French context, the term can also refer to negotiations “allowing voluntary actors to define a regulatory framework and more advanced mutual recognition of jointly defined efforts”.[6] India, on the other hand, has positioned itself, as described by Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar, as “an industry leader of such plurilateral groups”.[7] These groups, emerging from “the compulsions of common concerns,” are defined by Jaishankar as “coalitions of convenience” and characterised by a result-oriented cooperation approach “reconciled with contrary commitments”.

While the terminologies around plurilateral arrangements may differ in the strategic vocabularies of the two countries, there is some convergence in describing the form of minilateralism involving three actors and marked by its flexibility, its lack of institutional structure (no permanent headquarters or secretariat, no constitutive charter), and its informality (often taking place on the sidelines of multilateral summits). In essence, such formats represent an ad-hoc and voluntary mode of cooperation, “gathering the ‘critical mass’ of members necessary for a specific purpose, in contrast to the broad and inclusive approach associated with multilaterals”.[8] Highlighting the lack of a permanent institution typically associated with these arrangements, Alice Pannier explains that “direct coordination between governments and administrations” offers an alternative approach to addressing the necessity for defence cooperation, particularly when coalition interventions are commonplace.[9] Sebastian Haug et al. define minilaterals as “informal, non-binding, purpose-built partnerships, and coalitions of the interested, willing, and capable set up to address challenges in specific issue areas”.[10]

Beyond their emphasis on practical problem solving in specific areas, another crucial aspect of minilateral setups is the composition of the participating actors. These actors are often connected by factors such as their geographical proximity, shared strategic culture, or a common understanding of existing threats.[11] Indian diplomats and military officials concur on the value of minilateralism to support institutional frameworks, perceived as having limited initiative capacity, and overcome the inherent challenges of coordination within larger groups.[12] The informal and adaptable nature of minilaterals allows them to be a comfortable format for countries like India that are averse to formal security alliances. Minilaterals also address the limited capabilities and capacities of single actors by bringing together an assortment of solutions to advance member states’ shared interests.

Trilaterals with India and France in the Indo-Pacific

Minilaterals have been a frequent part of the architecture of the contested and strategic Indo-Pacific region, which has several such arrangements, including the Quad (India, Japan, Australia, and the US) and the I2U2 (India, Israel, the UAE, and the US). In the Indo-Pacific, minilateralism primarily brings together ‘like-minded partners’ rallying around 'shared values'. Minilaterals are perceived to be more effective due to their direct organisation and lower operational costs than multilateral institutions. The challenges associated with seeking consensus within multilateral bodies explain why “certain actors concurrently invest in more restricted arrangements aimed at achieving operational or ideological objectives or fostering political rapprochement”.[13] In this context, the numerous recent dialogues, especially trilateral dialogues, have aimed to establish practical cooperation mechanisms within a partnership framework. Some of these dialogues are characterised by their autonomous nature in relation to multilateral arrangements.[14] India’s increased involvement in trilateral dialogues has coincided with the rise of the Indo-Pacific concept. New Delhi participates in about a dozen such formats (see Table 1), of which ten have been initiated since the early 2010s, with half of them established after 2016, when the concept was already circulating in the strategic vocabulary of several countries.

Table 1: Trilateral Mechanisms Involving India

| Trilateral |

Year of Creation |

| India-China-Russia |

1990s |

| India-Brazil-South Africa |

2003 |

| India-USA-Japan |

2011 |

| India-USA-Afghanistan |

2012 |

| India-Japan-Australia |

2015 |

| India-Iran-Afghanistan |

2016 |

| India-Oman-Iran |

2017 |

| India-Australia-Indonesia |

2017 |

| India-France-Australia |

2020 |

| India-Japan-Italy |

2021 |

| India-Iran-Armenia |

2023 |

| India-France-UAE |

2023 |

Source: Authors’ own

While trilaterals are not new to India’s cooperation practices, as demonstrated by the India-China-Russia format in the 1990s and the IBSA with Brazil and South Africa in 2003, the focus of recent trilaterals has shifted towards key partners in the Indo-Pacific. Since 2011, India has established three trilaterals with Japan, three with Australia, two with the US, two with France, and one each with Indonesia and the UAE. However, these trilateral arrangements do not necessarily share the same objectives or aspirations. While some of these ad-hoc mechanisms are designed to achieve practical goals—such as the India-Iran-Afghanistan partnership under the Chabahar Agreement (2016), the India-Australia-Japan trilateral focused on supply-chain resilience, the India-Iran-Armenia trilateral aimed at boosting the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), or the India-Iran-Oman format centred on gas pipelines—at first glance, most of them appear to serve political and strategic purposes sometimes related to ideological objectives, such as a common understanding of threats and references to shared values.

On the French side, trilateral engagements date back to the early 1990s but remain relatively limited within France’s broader cooperative practices. In addition to participating in multilateral formats, France’s Indo-Pacific strategy is reflected in its increasing involvement in various minilateral arrangements. The signing of the FRANZ Arrangement with Australia and New Zealand in 1992 was followed, a few decades later, by the establishment of other more informal and politically oriented trilateral formats, especially in the Indo-Pacific context. The FRANZ Arrangement aimed for improved coordination of civil and military aid and resources from France, Australia, and New Zealand for Pacific Islands nations during natural disasters, as evinced in Papua New Guinea in 1998 and during cyclones in Fiji (2003, 2012, 2026), Solomon Islands (2003), Niue (2004), and Vanuatu (2010, 2015). The Arrangement differs from France’s more recent trilaterals in the Indo-Pacific context because of its greater institutional nature (a signed tripartite agreement), an extremely well-defined ambition (to aid the pooling of resources during natural disasters for Pacific Islands), and its operational and action-based nature (with regular follow-up annual meetings).

The India-France-Australia Trilateral

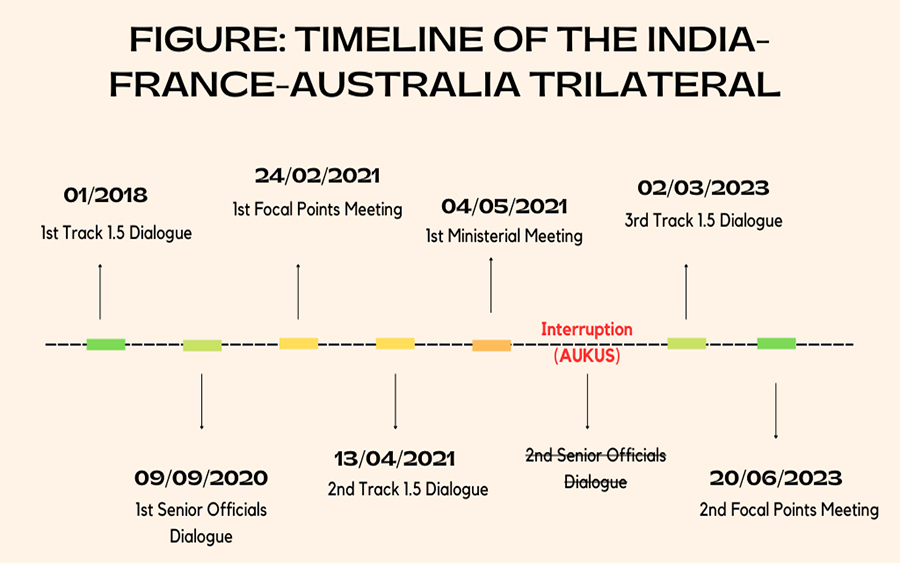

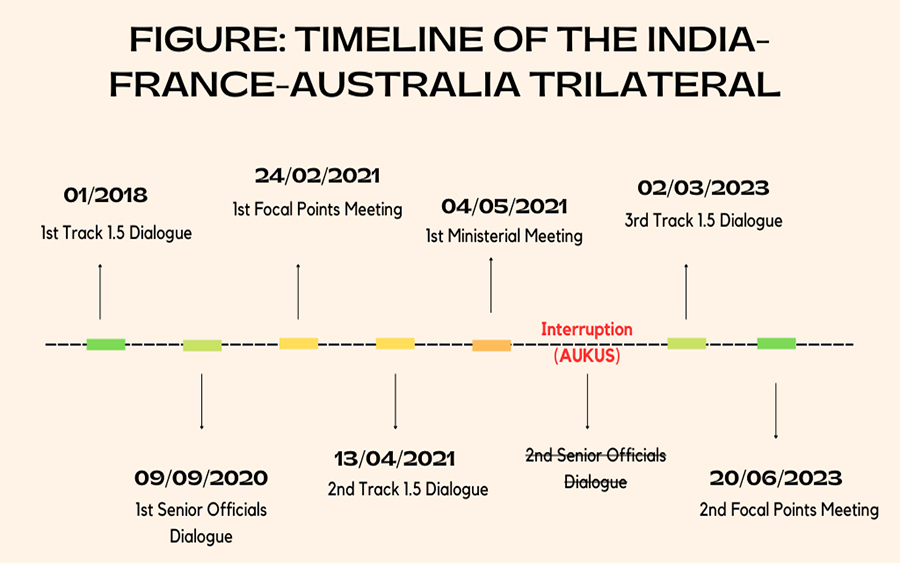

A trilateral mechanism between India, France, and Australia was established in September 2020 with the first senior officials’ dialogue, which was held virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic.[15] This meeting between the foreign secretaries of the three countries introduced the trilateral format within the India-France context at the official level. The meeting also marks the establishment of a longer political rapprochement between the three countries, which emerged in parallel to the Indo-Pacific diffusion in their strategic vocabularies. In such a context, France’s understanding of the Indo-Pacific at the presidential level, unveiled during Emmanuel Macron’s speech at Garden Island, Australia, in May 2018, was accompanied by a call for a Paris-Delhi-Canberra Axis, which was considered as “absolutely key to frame the region and frame our common interests in the Indo-Pacific,” with Australia and India being described here as “critical partners to this new Indo-Pacific alliance and axis”.[16]

The speech made a direct link between the trilateral axis and the India-France joint strategic vision for cooperation in the IOR, which was established two months prior. Consequently, the official trilateral was preceded by a Track 1.5 meeting in January 2018, which saw the involvement of experts and officials from the three countries. Besides being preceded by a more informal 1.5 format unlike the IFU, an initial lack of clarity in objectives also characterised the IFA. The statements released after the first meeting of the senior officials mentioned a vague focus on strengthening and enhancing cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region,[17] with discussions about broad economic and geostrategic challenges, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.[18] The issues discussed included the maritime sector and marine global commons, as well as strengthening and reforming multilateralism. This first meeting, therefore, laid the foundation for “concrete cooperation projects”,[19] “practical cooperation at the trilateral and regional level,” and an “outcome oriented” approach for the three stakeholders to meet regularly.[20]

Figure 1: Timeline of the India-France-Australia Trilateral

Source: Authors’ own

India’s September 2020 statement introduced three guidelines for the mechanism within the three countries: “synergising their respective strengths” in line with the objective of outcome-oriented cooperation; the need for practical cooperation, “including through regional organisations”; and the importance of “strong bilateral relations” between each of the participating nations as an underlying and indispensable condition for the trilateral to last.[21] The selectivity of such formats is often seen as enabling groups of actors that already interact within multilateral arenas to cooperate more effectively, without the constraints inherent to institutional processes.[22] When viewed through the lens of these objectives, the evolution of the trilateral dialogue between India, France, and Australia over the last three years yields several observations.

Synergising strengths for outcome-oriented action

The initial posture of the trilateral, which sought concrete cooperation through an outcome-oriented approach, has struggled to be effective due to the lack of a specific theme on which the three countries could work together in a complementary manner. The first Focal Points Meeting, held in February 2021 at the division-chief level, reaffirmed the objective of bringing forth “tangible projects in the region to ensure its security, prosperity and sustainable development”.[23] However, discussions around the proposals made during the senior officials’ meeting of September 2020 have raised doubts about the operationality of the format, primarily due to the number of themes mentioned in the statement and the lack of detail around further progress in this regard. The discussions focused on the five themes intended to guide joint trilateral action: maritime security, humanitarian assistance in disasters, the blue economy, marine resources and the environment, and multilateralism. While establishing the Focal Points Meeting aligns with the operationalisation of the trilateral, the number of identified cooperation axes perpetuates the dispersion of collective action and resources, which can only be effective when they address a limited number of specific issues and favour concrete, long-term cooperation projects.

The second Focal Points Meeting, which took place in June 2023 after a period of interruption due to the Franco-Australian diplomatic crisis following the announcement of the Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) security partnership (which also prevented the second senior officials’ dialogue), has contributed to streamlining the approach of the dialogue by focusing on three pillars: maritime safety and security, including Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR); global maritime commons and environment; and multilateral engagement.[24] These three pillars were already specified in the joint declaration emerging from the elevation of the trilateral dialogue to the foreign ministers’ level, who met for the first time in London on the sidelines of the G7 in May 2021.[25] Nevertheless, the dialogue was diluted given the multitude of common-interest topics under focus, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the situation in Myanmar, climate change, counterterrorism, and cybersecurity.

This heterogeneity of topics undermined the action-oriented approach initially desired by stakeholders and conveyed a lack of clarity and visibility in terms of cooperation among the three countries, especially to other regional partners. This dialogue risks becoming an exclusively political initiative guided solely by a convergence of shared values, without a tangible contribution to regional security and prosperity.

The India-Australia-Japan format, focusing on supply-chain resilience, and the FRANZ Arrangement between France, Australia, and New Zealand on HADR offer examples of trilaterals focusing effectively on a limited number of issues (with the latter having recently proven its concrete functionality by providing emergency help to the Kingdom of Tonga after a massive volcanic eruption). Therefore, in the India-France-Australia context, a clearer focus on maritime security and maritime safety issues, encompassing both traditional and non-traditional security approaches and including activities such as HADR, combating organised crime at sea, addressing illegal fishing, and environmental marine protection issues, would be worth considering. This approach makes even more sense as France is responsible for the ‘marine resources’ pillar and Australia leads the ‘marine ecology’ pillar within the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative (IPOI) launched by India in 2019.

Practical cooperation in multilateral arenas

Beyond prioritising “upholding and reforming”[26] multilateralism, the stated goal of the IFA to align with the main multilateral mechanisms of the region also reflects a desire to contribute effectively by pooling resources from a limited number of actors to direct them at efforts undertaken within broader regional deliberative frameworks to address certain transnational issues. By operationalising the general objectives identified within multilateral arenas, minilateral frameworks may be better accepted regionally than extra-regional initiatives, “whose functional significance seems secondary to strategic and political displays”.[27] India’s statement following the first senior official meetings mentioned establishing practical cooperation in this regard, “including through regional organisations such as ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations], IORA [Indian Ocean Rim Association], and the Indian Ocean Commission [IOC]”.[28] The foreign ministers’ meeting a few months later broadened the spectrum of relevant regional multilateral organisations for the trilateral action to include the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS), the East Asia Summit (EAS), and the Pacific Islands Forum. Furthermore, the joint statement extended beyond the Indo-Pacific region, discussing the possibility of coordinated actions within global institutions such as the World Health Organization, the UN Human Rights Council, and the G20.[29]

The risk of dilution of collective action and the resources mobilised within the trilateral format are accentuated by the multiple multilateral mechanisms available for the three countries. The ambiguity about the concrete objectives of this initiative and the means employed to achieve them also perpetuates the lack of clarity and functionality of the dialogue to regional partners. Moreover, several multilateral bodies do not include all three countries among their members, which then complicates practical trilateral cooperation within the three countries, such as the IOC, where Australia is not a participating country and India only holds observer status; the EAS, where France is absent; and the Pacific Islands Forum, where India and France are only dialogue partners.[a] Therefore, the trilateral dialogue would benefit from establishing mechanisms for enhanced coordination within multilateral formats in which all three countries are fully engaged (see Annexure).

In the fields of blue economy and marine environment, the three countries could leverage their pooled efforts to concretise and operationalise collectively agreed-upon objectives at the regional level within IORA, whether through ministerial-level conferences[b] or joint political declarations made in recent years.[c] In the realm of maritime security and safety, India, France, and Australia can make positive contributions to strengthening the role of the IONS and operational efforts in regional maritime security, alongside organising trilateral naval exercises to enhance synergy, coordination, and interoperability among the three navies. The trilateral information sharing workshop on maritime domain awareness, created in the India-led Information Fusion Centre-Indian Ocean Region and including liaison officers deployed by France and Australia, is a positive step in this direction.[30]

The strength of bilateral ties

The strength of the bilateral relationships between the three countries is also crucial for the effectiveness and functionality of the trilateral format. Like the relationship between India and Australia, the bilateral relationship between France and India has significantly strengthened in recent years. This strengthening has been particularly evident through a shared engagement and convergent understanding of the Indo-Pacific concept. Both countries share an ambition for strategic autonomy and a multipolar world, as well as a common perception of the geographic scope covered by the concept. The areas of cooperation between the two countries include counterterrorism, combating piracy and organised crime, environmental security, and the fight against illegal fishing. This increased cooperation has been accompanied by enhanced naval cooperation on an operational level. It has also been marked by joint patrols in the Indian Ocean in 2019 and 2022, and the signing of a logistics support agreement in March 2018, which granted the Indian Navy access to the French military base in La Réunion. At a broader regional level, the Indo-Pacific Parks Partnership, announced in 2022,[31] serves as an example of both countries’ willingness to leverage bilateral efforts to benefit the broader region.

However, an unprecedented diplomatic crisis between France and Australia also impacted the Paris-New Delhi-Canberra axis, following the announcement of AUKUS in September 2021 and the cancellation of the submarine deal between the two countries. It also highlighted the sensitivity of trilateral mechanisms to changes in bilateral relations among members; the crisis interrupted interactions with the trilateral dialogue with India and derailed the organisation of the second senior officials’ working group, initially announced for the second half of 2021.[32]

According to some experts, a combination of factors led to the progressive normalisation of relations between the two countries: Canberra’s recognition of France as a key player in the Indo-Pacific; the payment of US$835 million for the cancellation of the agreement; and, most importantly, the change in leadership in Australia in May 2022.[33] This was evident during the visit of the new Australian Prime Minister, Anthony Albanese, to Paris in July 2022, during which Australia and France expressed their ambition to build a closer and stronger relationship centred on a new cooperation agenda.[34] In addition to ongoing discussions regarding reciprocal access to military infrastructure,[35] the second Franco-Australian 2+2 format meeting (foreign and defence ministers) convened in January 2023 also announced a joint project to produce 155mm ammunition to support Ukraine against Russia’s invasion.[36] The joint statement issued following the meeting also highlighted bilateral ambitions concerning biodiversity, HADR, and maritime security in the Pacific region and, more broadly, in the Indo-Pacific region. This underscores the relevance of concrete collaboration efforts within the IFA trilateral framework, especially since these issues also play a significant role in the France-India bilateral relationship in the region.[37]

The resumption of the trilateral dialogue, first in a Track 1.5 format in March 2023 on the sidelines of the Raisina Dialogue and more officially through the second Focal Points Meeting in June, provides new possibilities and opportunities for the three countries to rethink the trilateral initiative by concretely implementing the various objectives that were originally formulated. Thus, in light of the experience gained since 2020, synergising strengths around an outcome-oriented approach, coordinating action within relevant multilateral mechanisms, and ensuring strong bilateral relations are essential for the functioning of new trilateral mechanisms involving France and India in the Indo-Pacific region, as outlined in the France-India roadmap of July 2023. This is particularly true for the new trilateral format between India, France, and the UAE, which was formalised in February 2023.

The India-Frane-UAE Trilateral

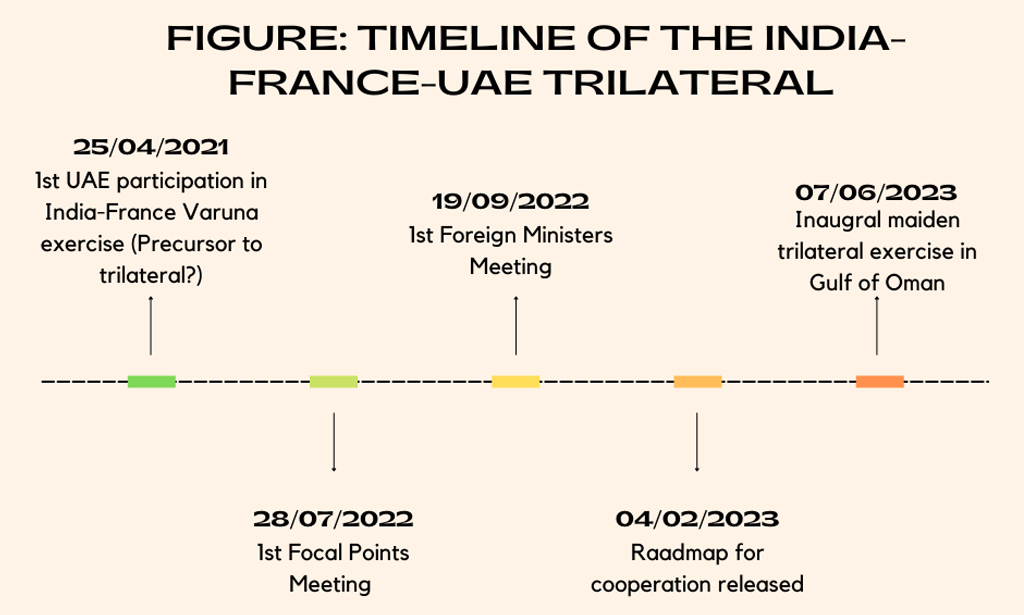

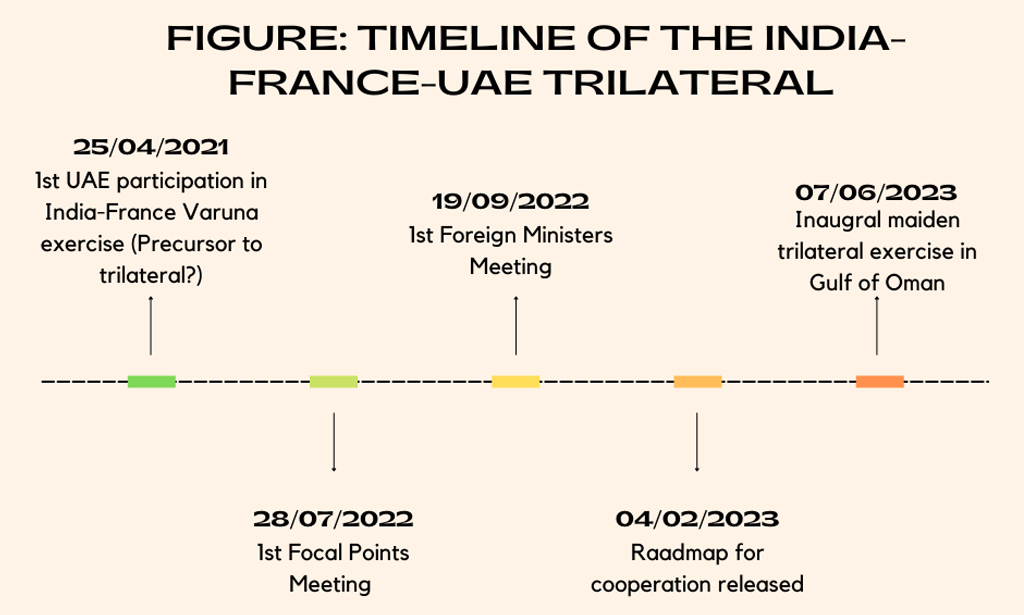

Just as the AUKUS trilateral, which included a deal between the US and the UK to supply submarines to Australia, was announced, another trilateral, comprising India, the UAE, and France, was also underway. This trilateral, while still in its infancy, is underpinned by well-established bilateral relations that have strong political, economic, and security convergences.

Figure 2: Timeline of the India-France-UAE Trilateral

Source: Authors’ own

Robust bilateral partnerships

France is India’s oldest comprehensive strategic partnership, signed in 1998, involving extensive cooperation in sectors ranging from security and space to climate and the blue economy. France has emerged as a strong defence partner, particularly as India seeks alternative suppliers from Russia in its quest for military modernisation. Similarly, the UAE has embarked on a military modernisation programme while seeking alternative arms exporters in the wake of American retrenchment from the Gulf. India and the UAE are buyers of French Rafale jets, paving the way for three-way joint exercises and training.

Simultaneously, a strategic partnership and several high-level visits since 2008 have also strengthened France-UAE ties. Interestingly, on the day AUKUS was announced (15 September 2021), Macron was hosting Emirati leader Mohammed bin Zayed in Paris. France’s first Gulf military base is in Abu Dhabi, and large volumes of France’s energy needs transit through the West Indian Ocean (WIO) region. The UAE also hosts the Gulf’s largest French community, of 35,000 expats and 600 companies.[38] Security cooperation has grown, and in 2022, France activated the countries’ 1995 defence agreement after a Houthi-led drone attack.[39]

India-UAE relations have moved beyond remittance flows to include cooperation in energy, food security, and defence sectors. Ties have rapidly progressed since the signing of the India-UAE Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, which aims to double non-oil bilateral trade from US$48 billion in 2022–23 to over US$100 billion by 2030.[40] The two countries also share economic complementarities, such as the UAE’s status as a primary energy supplier for the rapidly growing Indian economy.

Over the years, intra-Gulf rivalries have resulted in military bases and commercial ports emerging as points of competition, with the UAE being among the strongest players.[41] On the other hand, the UAE and France have found congruence on regional issues such as Libya and the Eastern Mediterranean,[42] where, along with India, they are enhancing ties with Greece to balance challenging relations with Türkiye. West Asian realignments, such as the normalisation of UAE-Israel ties, further unleash the region’s potential.

Geographical scope

While the IFA focuses largely on the Pacific within the broader Indo-Pacific construct, the IFU’s focus is the Indian Ocean, specifically the WIO subregion at the crossroads of three continents—Asia, Africa, and Europe. The WIO extends “from the Red Sea, along coastal East Africa, to the Gulf of Oman and the island nations of the Arabian Sea”.[43] A large chunk of international maritime trade flows through this region, which includes sea lanes of communication and choke points such as the Strait of Hormuz, the Mozambique Channel, the Bab al-Mandab Strait, and the Gulf of Aden. In addition to the natural assets of fisheries, coral reefs, and mangroves, the region’s importance has increased owing to its vast energy resources in the context of the Russia-Ukraine war, rendering maritime security and freedom of navigation vital.

India’s SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region) vision includes the entire Indian Ocean and the WIO subregion in its definition of the Indo-Pacific and is “a way to re-engage with the region”, particularly in the context of China’s rising influence.[44] Amid wider geopolitical competition, the WIO constitutes a vital area in India’s strategic outlook, as identified in its 2015 Maritime Strategy,[45] rendering relations with the Gulf and key island states such as Mauritius and the Seychelles imperative. This explains India’s naval presence as a regional security provider, particularly in non-traditional security areas such as HADR operations, and through port calls and joint naval exercises with countries like Tanzania and Mozambique.[46] India considers West Asia its extended neighbourhood, and its stakes in the Gulf include the security of a sizeable diaspora population. Therefore, a strategic footprint with the UAE at its core l is crucial for India. With its pivot to Africa, as evident during its G20 presidency, India has also prioritised relations with the African continent.

Similarly, France, with its vast geographical definition of the Indo-Pacific, “from Djibouti to Polynesia,” accords prominence to the WIO in its Indo-Pacific strategy and to India as its preferred partner in the Indian Ocean.[47] With over 1.6 million French citizens and major exclusive economic zones, France is a resident power in the WIO through its overseas territories of Mayotte and Réunion. This explains France’s consequential military presence in the WIO, including a military base in its erstwhile colony Djibouti, in addition to bases in Mayotte, Réunion, and the UAE.

Thus, there are definitive convergences in the WIO region’s importance for both India and France, with resultant aims to be stabilising powers. Yet, India’s more immediate security challenges at its borders and France’s security challenges in Europe, besides substantial colonial baggage in Africa, limit Indian and French capabilities, making cooperation with partners central to achieving interests. This is where the UAE comes in.

In recent years, the UAE has developed a more ambitious foreign policy, intending to become a prominent regional hub by diversifying from being a predominantly oil-based economy to a more balanced trade- and knowledge-oriented economy.[48] To attain the UAE’s goal of becoming “the node of nodes” across continents in the context of intra-Gulf rivalries,[49] it is vital to secure the WIO from the spillover of crises in Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Myanmar, and Mozambique; ensuring the stability of trade routes; and enhancing connectivity. Through its “string of ports” strategy, the UAE has undertaken massive investments in the region’s ports and expanded its strategic footprint in Africa.[50] Thus, the UAE is a credible alternative to China’s ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ and infrastructure projects under its Belt and Road Initiative. Increased naval and military deployments, such as a strategic base in Djibouti on the coast of the Horn of Africa in 2017, have accompanied China’s predatory investments.

Compared to the IFA, the IFU trilateral may be more useful for India since its interests are more oriented towards the Indian Ocean rather than the Pacific Ocean. France is an Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean country, with overseas territories in both oceans.[51] On the contrary, Australia employs a narrower geographical scope to define the Indo-Pacific and includes only the Eastern Indian Ocean region (and not the WIO) while devoting greater attention to the Pacific.[52] The Pacific Ocean is also the focus of US engagement, although it has expanded its definition of the Indo-Pacific to include the entire Indian Ocean, with the aim of integrating African countries. Yet, even while the Eastern Indian Ocean receives some American attention, the WIO remains largely neglected,[53] leaving an important vacuum for the IFU trilateral to address.

Scripting a third way

A striking factor that differentiates the IFU trilateral from the IFA is its vision. Unlike Australia, with its unipolar world vision with the US at its core, India, France, and the UAE aspire for a thriving multipolar order that allows them to retain their strategic options.

The IFU trilateral brings together three middle powers, each with a keen interest in preserving strategic autonomy—“the ability of a state to pursue its national interests and adopt its preferred foreign policy without being constrained in any manner by other states”.[54] Diverse partnerships are a means to enhance this strategic autonomy—a goal that has gained greater momentum in the geopolitical context of the heightening US-China power competition.

Macron outlined this approach in April 2022, saying, “The aim of France is not to submit to the great divisions that paralyse, but to know how to exchange with each region and continue to build new alliances”.[55] For India as well, cooperation with partners to secure the global commons is more important than a club against a particular country.[56] The UAE has a ‘multi-aligned’ foreign policy, where it partners with India and France as well as with China to enhance its leverage with traditional partners like the US.

Moreover, several minilaterals (such as the Quad and the I2U2) and security alliances (such as AUKUS) include the US, which is often perceived by West Asian countries as a driver of regional instability. In addition, the humiliating French experience from AUKUS, pressures attached to acquiring the American F-35 fighter jets involving limiting Huawei in the UAE’s 5G networks,[57] and India’s objections to expanding US naval presence in areas such as the Lakshadweep islands[58] have lent greater credibility to the rationale for the IFU trilateral.

China is a vital partner in the UAE’s economic diversification, and bilateral security ties are also expanding, with reports of a Chinese military base being set up in the UAE.[59] The UAE’s “mercantile grand strategy of controlling access to key maritime checkpoints in the Indian Ocean, the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea, made Abu Dhabi an important partner for Beijing”.[60] Yet, despite the UAE’s divergent outlook on China, the preference for strategic autonomy means that India, France, and the UAE do not factor in strong conditions in their foreign relations, choosing to focus on alignments rather than differences.

Priority areas for cooperation

A multitude of factors renders the UAE an ideal country to join the trilateral format with India and France. This includes a progressive foreign policy, a strategic location in West Asia, robust bilateral partnerships with both India and France, a wealth of financial assets for a nation of only nine million people, and a shared interest in strategic autonomy.

Despite the trilateral being in a nascent stage, convergences and complementarities between the three countries provide a strong impetus for cooperation. The following priority areas— some of which have been identified in the roadmap for cooperation released in February 2023—could help maximise potential and result in action-based outcomes.[61]

The roadmap acknowledges defence, including joint development and co-production, as an area for close cooperation. Indian and Emirati purchases of the French Rafales provide solid foundations while demonstrating that France is a less complicated arms supplier with nominal preconditions than the US. The Emirati Air Force’s midair refuelling support for India’s Rafales already constitutes significant trilateral defence cooperation.[62] India and the UAE aim to develop their indigenous defence capacities, and through France, the trilateral can play a role in the transfer of technology. Companies across the three countries are engaging in co-development activities; for instance, India’s HAL and UAE’s EDGE plan to co-develop missile systems and unmanned aerial vehicles.[63]

Maritime security is another relevant area. Building on the Gulf of Oman’s trilateral exercise, existing bilateral exercises can be trilateralised to focus on specific chokepoints and monitor fishing, piracy, and other illegal activities. The trilateral can also provide security alternatives to the WIO’s littoral states and small island states, which have limited capacities and rely on outside powers for stability. Surveillance, maritime domain awareness, and HADR operations could be areas for engagement. The IPOI, aimed at progress in the blue economy through the ecological use of marine resources, and the India-France Triangular Development Cooperation Fund, with its goal of supporting sustainability-focused start-ups from third countries, can also provide avenues.[64]

Energy transition is a priority, given that all three countries are members of the International Solar Alliance (ISA) spearheaded by India and France. The UAE has some of the world’s most affordable solar electricity worldwide, at 2.5 cent per kilowatt hour,[65] and is looking to move away from its traditional association with fossil fuels. Existing bilateral initiatives, such as developing hydrogen technologies and increasing renewable capacities, can be trilaterised. The trilateral could provide clean energy solutions and build climate-resilient infrastructure in African countries, many of which are members of the ISA, as well as in climate-vulnerable island states.

Given the disruptive impact of the Russia-Ukraine war, the issue of food security can also be addressed by the IFU trilateral. The Global Report on Food Crises estimates that, in 2022, 258 million people across 58 countries faced acute food insecurity.[66] India and the UAE are already cooperating in this sector through the I2U2, where Emirati funding is building agricultural parks in India. France is well known for its agricultural technological innovations, and despite the potential overlap of initiatives with the I2U2, an issue of this magnitude requires the attention of multiple actors. In addition, the Israel-Palestine war could impact some of the initiatives under the I2U2, given the grouping’s foundations based on the Abraham Accords and the normalisation of ties between Israel and the UAE.

- Development projects in third countries

The trilateral can take a leaf out of the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor between India and Japan that focuses on development projects in Africa. India and the UAE already have joint projects in the healthcare sector in Tanzania and Kenya. To boost connectivity and growth in the WIO region, trade and logistics infrastructure (such as ports) may be prioritised, given the UAE’s expertise in this domain.

Despite the trilateral’s Indian Ocean focus, each country is also individually building infrastructure in the Pacific, where Macron warned against “a new imperialism”.[67] The UAE has spent over US$50 million on renewables projects in climate-vulnerable Pacific islands,[68] while India is establishing a superspecialty cardiology hospital in Fiji and also expanding its solar STAR-C initiative to the Pacific island nations.[69] The trilateral can coordinate some of these disjointed efforts and pool in capacities to make a greater difference.

Extremism from non-state actors afflicts all three countries, and there is substantial bilateral cooperation, such as through annual counterterrorism working groups. The trilateral can push for the adoption of the Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism at the UN, which provides a universal definition of terrorism and a legal framework to deny funds and safe havens to terror groups.[70] As the current chair of the Counter-Terrorism Committee, the UAE can encourage other Organisation of Islamic Cooperation members that continue to oppose the convention first proposed by India in 1996 to come on board.

- Other areas of cooperation

The roadmap also identifies cultural cooperation through joint projects. Abu Dhabi already hosts a branch of France’s Louvre Museum and campuses of the French universities INSEAD and the Sorbonne. The Indian Institute of Technology is also slated to open a campus in the Emirati capital. But there is substantial scope to scale up educational exchanges. For instance, only 10,000 Indian students currently study in France compared to 34,000 in Germany.[71]

Since France and the UAE have adopted India’s United Payments Interface system, which facilitates cashless transactions, the trilateral can play a role in expanding India’s digital public infrastructure and services to developing countries in the Global South to foster inclusive development and bridge the digital divide.

Conclusion

The IFU brings together the complementary advantages of each of the three countries—namely, Emirati financial capacity, Indian human resources, and French technologies. By leveraging these strengths, the trilateral can play a crucial balancing role both in the WIO and the wider Indo-Pacific region while providing alternatives to other countries that are free from the constraints of great power competition. With its focus on preserving strategic autonomy and providing common public goods, the IFU trilateral is less vulnerable to internal geopolitical divergencies undermining its agenda and cohesion. Yet, it is important to note that several of these outcomes and cooperation through the IFU could be contingent on how the Israel-Palestine war evolves, given the geopolitical risks and uncertainties associated with a conflict of this nature and scale.

This paper has taken different approaches to both trilaterals, with a more critical approach adopted towards the IFA, an older trilateral that is yet to achieve significant results. The IFU, on the other hand, is still in its early stages. Therefore, the paper adopts a more futuristic and positive approach towards this trilateral.

Annexure: Membership in Key Multilateral Mechanisms

| Organisation and Grouping (International) |

India |

France |

Australia |

UAE |

| UN Security Council |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| G20 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Guest country during India’s presidency |

| G7 |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| BRICS |

Yes |

No |

No |

New member |

| Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Member of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) |

| Organisation (Regional) |

India |

France |

Australia |

UAE |

| Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) |

Observer |

Yes |

No |

No |

| Pacific Community |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Pacific Islands Forum |

Dialogue partner |

Dialogue partner (French Polynesia and New-Caledonia as members) |

Yes |

No |

| Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) |

Yes |

No |

No |

Dialogue partner |

| APG (Asia Pacific Group on Money Laundering) |

Yes |

Observer |

Yes |

Observer |

| Dialogue and Forum (Regional) |

India |

France |

Australia |

UAE |

| East Asia Summit (EAS) |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

| ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) |

Yes |

Member through the EU |

Yes |

No |

| Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative (IPOI) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| ADMM+ |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Western Pacific Naval Symposium (WPNS) |

Observer |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| South Pacific Defence Ministers’ Meeting (SPDMM) |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Conference on Interaction & Confidence-Building Measure sin Asia (CICA) |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Asia-Middle East Dialogue (AMED) |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Information Sharing Centre (Regional) |

India |

France |

Australia |

UAE |

| ReCAAP Information Sharing Centre |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Information Fusion Centre (IFC) |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Information Fusion Centre – Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Endnotes

[a] If France is considered a dialogue partner, the territories of French Polynesia and New Caledonia are part of the 18 permanent members of the Forum.

[b] On the blue economy in 2015, 2017, and 2019; on the management and sustainable development of fisheries resources in 2017; or on renewable energies in 2014 and 2018.

[c] Such as the Dhaka Declaration on the Blue Economy in 2019; the Delhi Declaration on Renewable Energy in the Indian Ocean Region in 2018; and the Declaration of IORA on the Principles for Peaceful, Productive and Sustainable Use of the Indian Ocean and its Resources in 2013.

[1] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, India-France Indo-Pacific Roadmap, July 14, 2023, https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/36799/IndiaFrance+IndoPacific+Roadmap.

[2] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Joint Strategic Vision of India-France Cooperation in the Indian Ocean Region, March 10, 2018, https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/29598.

[3] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, India-France Indo-Pacific Roadmap

[4] Ministry of Europe and External Affairs (France), Union européenne – Participation de Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne à la visioconférence des ministres de l’Union européenne chargés du commerce [European Union - Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne takes part in the videoconference of European Union trade ministers], June 9, 2020, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/la-france-et-l-europe/evenements-et-actualites-lies-a-la-politique-europeenne-de-la-france/actualites-europeennes/article/union-europeenne-participation-de-jean-baptiste-lemoyne-a-la-visioconference.

[5] Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, French Government, Traité entre la République française et la République italienne. Pour une coopération bilatérale renforcée [Treaty between the French Republic and the Italian Republic. For enhanced bilateral cooperation], November 26, 2021, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/26_11_2021_traite_bilateral_franco-italien_cle07961c.pdf.

[6] Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, French Government, Propositions françaises pour la révision de la stratégie de politique commerciale de l’UE [French proposals for revising the EU's trade policy strategy], November 20, 2020, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/propositions_francaises_pour_la_revision_de_la_strategie_de_politique_commerciale_de_l_ue_cle8efbbc.pdf.

[7] Subrahmanyan Jaishankar, The India Way: Strategies for an Uncertain World, (Harper Collins India, 2020), pp. 37.

[8] Aarshi Tirkey, “Minilateralism: Weighing the Prospects for Cooperation and Governance”, ORF Issue Brief No. 489, September 2021, Observer Research Foundation, https://www.orfonline.org/research/minilateralism-weighing-prospects-cooperation-governance/.

[9] Alice Pannier, “Le ‘minilatéralisme’ : une nouvelle forme de coopération de défense” [Minilateralism: a new form of defence cooperation], No. 1, 2015, p. 37-48, Politique étrangère, https://www.cairn.info/revue-politique-etrangere-2015-1-page-37.htm.

[10] Sung-Mi Kim, Sebastian Haug, and Susan Harris Rimmer, “Minilateralism Revisited: MIKTA as Slender Diplomacy in a Multiplex World,” Global Governance 24, 4, Pg 478 (2018), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332154294_Minilateralism_Revisited_MIKTA_as_Slender_Diplomacy_in_a_Multiplex_World.

[11] Pannier, “Le ‘minilatéralisme’ : une nouvelle forme de coopération de défense”.

[12] Interviews conducted in New Delhi, March 2023.

[13] Delphine Allès and Thibault Fournol, “Multilateralisms and minilateralisms in the Indo-Pacific. Articulations and convergences in a context of saturation of cooperative arrangements”, Fondation pour la recherche stratégique, June 28, 2023, https://www.frstrategie.org/en/publications/recherches-et-documents/multilateralisms-and-minilateralisms-indo-pacific-articulations-and-convergences-context-saturation-cooperative-arrangements-2023.

[14] Allès and Fournol, “Multilateralisms and minilateralisms in the Indo-Pacific. Articulations and convergences in a context of saturation of cooperative arrangements”.

[15] Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Government of Australia, https://www.dfat.gov.au/news/media-release/first-australia-india-france-trilateral-dialogue.

[16] French Government, Déclaration de M. Emmanuel Macron, Président de la République, sur les relations entre la France et l'Australie, à Sydney le 2 mai 2018 [Statement by Mr Emmanuel Macron, President of the Republic, on relations between France and Australia, in Sydney on May 2, 2018], May 2, 2018, https://www.vie-publique.fr/discours/206113-declaration-de-m-emmanuel-macron-president-de-la-republique-sur-les-r.

[17] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, https://www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/32950/1st+Senior+Officials+IndiaFranceAustralia+Trilateral+Dialogue.

[18] French Embassy in India, The Indo-Pacific: 1st Trilateral Dialogue between France, India and Australia, September 9, 2020, https://in.ambafrance.org/The-Indo-Pacific-1st-Trilateral-Dialogue-between-France-India-and-Australia.

[19] French Embassy in India, The Indo-Pacific: 1st Trilateral Dialogue between France, India and Australia.

[20] Ministry of External Affairs, 1st Senior Officials’ India-France-Australia Trilateral Dialogue.

[21] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, https://www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/32950/1st+Senior+Officials+IndiaFranceAustralia+Trilateral+Dialogue.

[22] Allès and Fournol, “Multilateralisms and minilateralisms in the Indo-Pacific. Articulations and convergences in a context of saturation of cooperative arrangements”.

[23] Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, French Government, Indo-Pacific – Trilateral dialogue between France, India and Australia – First focal points meeting, February, 24, 2021, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/asia-and-oceania/news/article/indo-pacific-trilateral-dialogue-between-france-india-and-australia-first-focal.

[24] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, https://www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/36688/IndiaFranceAustralia+Trilateral+DialogueSecond+Focal+Points+Meeting.

[25] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, India-France-Australia Joint Statement on the occasion of the Trilateral Ministerial Dialogue, May 5, 2021, https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/33845/IndiaFranceAustralia_Joint_Statement_on_the_occasion_of_the_Trilateral_Ministerial_Dialogue_May_04_2021.

[26] French Embassy in India, The Indo-Pacific: 1st Trilateral Dialogue between France, India and Australia.

[27] Allès and Fournol, “Multilateralisms and minilateralisms in the Indo-Pacific. Articulations and convergences in a context of saturation of cooperative arrangements”.

[28] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, https://www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/32950/1st+Senior+Officials+IndiaFranceAustralia+Trilateral+Dialogue.

[29] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, India-France-Australia Joint Statement on the occasion of the Trilateral Ministerial Dialogue, May 5, 2021, https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/33845/IndiaFranceAustralia_Joint_Statement_on_the_occasion_of_the_Trilateral_Ministerial_Dialogue_May_04_2021.

[30] Ministry of External Affairs, India-France-Australia Joint Statement on the occasion of the Trilateral Ministerial Dialogue.

[31] Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, French Government, Indo-French call for an “Indo-Pacific Parks Partnership” Joint Declaration, February 20, 2022, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/india/news/article/indo-french-call-for-an-indo-pacific-parks-partnership-joint-declaration-paris.

[32] Ministry of External Affairs, India-France-Australia Joint Statement on the occasion of the Trilateral Ministerial Dialogue.

[33] Eglantine Staunton, “France-Australia: Salving the wounds of AUKUS”, The Interpreter, Lowy Institute, February 2, 2023, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/france-australia-salving-wounds-aukus.

[34] Charles Edel and Pierre Morcos, “Time to Reboot Franco-Australian Relations”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 7, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/time-reboot-franco-australian-relations.

[35] Presidency of the French Republic, French Government, Joint statement by France and Australia , July 1, 2022, https://www.elysee.fr/en/emmanuel-macron/2022/07/01/joint-statement-by-france-and-australia.

[36] Staunton, “France-Australia: Salving the wounds of AUKUS”.

[37] Department of Defence, Government of Australian, Joint statement - Second France-Australia Foreign and Defence Ministerial Consultations, January 30, 2023, https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/statements/2023-01-30/joint-statement-second-france-australia-foreign-and-defence-ministerial-consultations.

[38] Country Files, The Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, France and United Arab Emirates, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/united-arab-emirates/france-and-united-arab-emirates-65102/.

[39] Louis Vitrand, “UAE and France: A Key, and Challenging, Relationship”, September 07, 2023, Foreign Policy Research Institute, https://www.fpri.org/article/2023/09/uae-and-france-a-key-and-challenging-relationship/.

[40] “India-UAE agree to raise non-petroleum bilateral trade to $100 billion by 2030: Piyush Goyal”, The Economic Times, June 12, 2023, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/india-uae-non-petroleum-bilateral-trade-to-be-100-billion-by-2030-piyush-goyal/articleshow/100929744.cms?from=mdr.

[41] Eleonara Ardemagni, “Gulf Powers: Maritime Rivalry in the Western Indian Ocean”, Italian Institute for International Political Studies, April 11, 2018, https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/gulf-powers-maritime-rivalry-western-indian-ocean-20212.

[42] Abel Abdel Ghafar and Silvia Colombo, "France and the UAE: A deepening partnership in uncertain times”, Brookings Institution, October 28, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/france-and-the-uae-a-deepening-partnership-in-uncertain-times/.

[43] Rushali Saha, "Western Indian Ocean: The Missing Piece in the US Indo-Pacific Strategy, South Asian Voices, September 26, 2022, https://southasianvoices.org/western-indian-ocean-the-missing-piece-in-the-u-s-indo-pacific-strategy/.

[44] Shivali Lawale and Talmiz Ahmad, “UAE-India-France Trilateral: A Mechanism to Advance Strategic Autonomy in the Indo-Pacific?”, Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, Vol. 15, Issue, January 06, 2022, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/25765949.2021.2024401.

[45] Indian Navy, Indian Maritime Strategy, 2015, https://www.indiannavy.nic.in/content/indian-maritime-security-strategy-2015.

[46] "India Sees Itself As Net Security Provider in Indian Ocean Region”, NDTV, September 16, 2021, https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/india-sees-itself-as-net-security-provider-in-indian-ocean-region-ambassador-taranjit-singh-sandhu-2541662.

[47] Wada Haruko, “The Indo-Pacific Concept: Geographical Adjustments and Their Implications”, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Working Paper No. 326, March 16, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep24283?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

[48] Mohammed Soliman, ”I2U2 lies at the core of India-UAE relationship”, Hindustan Times, July 18, 2023, https://www.hindustantimes.com/opinion/i2u2-lies-at-the-core-of-india-uae-relationship-101689686967588.html.

[49] Eleonara Ardemagni, “Across the Regions: The UAE’s Network Approach to Cooperation”, Italian Institute for International Political Studies, March 10, 2023, https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/across-the-regions-the-uaes-network-approach-to-cooperation-119375.

[50] Brian Gicheru Kinyua, “UAE’s Overarching Role in African Ports Development”, The Maritime Executive, July 23, 2023, https://maritime-executive.com/article/uae-s-overarching-role-in-african-ports-development#:~:text=“This%20string%20of%20ports%20strategy,hub%20linking%20Africa%20and%20Asia.

[51] Nicolas Mazzucchi, “The French Strategy for the Indo-Pacific and the issue of European cooperation”, The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, April, 2023, https://hcss.nl/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/04-Nicolas-Mazzucchi-The-French-Strategy-for-the-Indopacific-and-the-issue-of-European-cooperation.pdf.

[52] Commodore Lalit Kapur (Retd), “Reviving India-France-Australia Trilateral Cooperation in the Indian Ocean”, Delhi Policy Group, Policy Brief July 18, 2022, https://www.delhipolicygroup.org/publication/policy-briefs/reviving-india-france-australia-trilateral-cooperation-in-the-indian-ocean.html.

[53] Saha, "Western Indian Ocean: The Missing Piece in the US Indo-Pacific Strategy”.

[54] “Aravind Devanathan asked: What is ‘strategic autonomy’? How does it help India's security?”, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, January 20, 2015, https://idsa.in/askanexpert/strategicautonomy_indiasecurity.

[55] “The Alternative to a ‘China Versus U.S.’ World”, Asia Society, April 20, 2022, https://asiasociety.org/switzerland/alternative-china-versus-us-world.

[56] Priya Chacko and Jeffrey Wilson, “Australia, Japan and India: A Trilateral Coalition in the Indo-Pacific?”, Perth US Asia Centre, September 2020, https://perthusasia.edu.au/getattachment/Our-Work/Australia,-Japan-and-India-A-trilateral-coalition/PU-175-AJI-Book-WEB(2).pdf.aspx?lang=en-AU.

[57] Nick Wadhams and Sylvia Westall, “Biden Prods UAE to Dump Huawei, Sowing Doubts on Key F-35 Sale”, Bloomberg, June 11, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-06-11/biden-prods-uae-to-dump-huawei-sowing-doubts-on-key-f-35-sale#xj4y7vzkg.

[58] Rezaul H Laskar, Rahul Singh, “India objects to US Navy operations near Lakshadweep”, Hindustan Times, April 10, 2021, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-objects-to-us-navy-ops-near-lakshadweep-101617992954884.html.

[59] John Hudson, Ellen Nakashima and Liz Sly, “Buildup resumed at suspected Chinese military site in UAE, leak says”, The Washington Post, April 26, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2023/04/26/chinese-military-base-uae/.

[60] Andreas Krieg, “The UAE’s tilt to China”, Middle East Eye, October 1, 2020, https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/why-security-partnership-between-abu-dhabi-and-beijing-growing.

[61] French Embassy in New Delhi, France-India-UAE - Establishment of a Trilateral Cooperation Initiative, February 04, 2023, https://in.ambafrance.org/France-India-UAE-Establishment-of-a-Trilateral-Cooperation-Initiative.

[62] Shishir Gupta, “UAE Air Force to help 3 Rafale fighters reach India, 7 more in April”, Hindustan Times, January 22, 2021, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/in-a-first-3-rafales-reaching-india-to-be-refuelled-mid-air-by-uae-air-force-101611209885564.html.

[63] “Abu Dhabi defence firms signs MoU with India’s HAL at UAE’s defence expo”, Live Mint, February 23, 2023, https://www.livemint.com/news/india/abu-dhabi-defence-firm-signs-mou-with-india-s-hal-at-uae-s-defence-expo-11677109205445.html.

[64] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Horizon 2047: 25th Anniversary of the India-France Strategic Partnership, Towards A Century of India-France Relations, July 14, 2023, https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/36806/Horizon_2047_25th_Anniversary_of_the_IndiaFrance_Strategic_Partnership_Towards_A_Century_of_IndiaFrance_Relations.

[65] Ashwani Kumar, “Solar energy is integral element of UAE's climate response, says Minister”, Khaleej Times, July 25, 2023, https://www.khaleejtimes.com/business/energy/solar-energy-is-integral-element-of-uaes-climate-response-says-minister%2523:~:text=Dr%252520Ajay%252520Mathur%25252C%252520Director%252520General,energy%252520in%252520the%252520Asia%252520Pacific.

[66] Food Security Information Network, “Global Report on Food Crises 2023”, World Food Programme, May 02, 2023, https://www.wfp.org/publications/global-report-food-crises-2023.

[67] “Emmanuel Macron denounces ‘new imperialism’ in Pacific on historic visit to Vanuatu",The Guardian, July 27, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jul/27/emmanuel-macron-vanuata-visit-pacific-imperialism.

[68] Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “UAE-Pacific Partnership Fund”, United Nations, https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/uae-pacific-partnership-fund.

[69] “PM Modi announces 12-point new development initiatives for Pacific Island nations”, May 22, 2023, India Today, https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/pm-narendra-modi-12-point-development-agenda-for-pacific-island-nations-2382854-2023-05-22.

[70] “What is the Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism?”, Live Mint, September 28, 2016, https://www.livemint.com/Politics/Ee84kLhbyP5NJ9mFnMzkKO/Will-Sushmas-speech-at-the-UNGA-give-fresh-push-to-antiter.html

[71] Christophe Jaffrelot, “How strategic are France’s relations with India?”, Le Monde Diplomatique, 2023, https://mondediplo.com/2023/07/14india-france.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV