-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Oommen C Kurian, “In the Shadow of COVID-19: Reimagining BIMSTEC’s Health Futures,” ORF Issue Brief No. 414, October 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

Established in 1997, the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multisectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) comprises five countries from South Asia (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka) and two countries from Southeast Asia (Myanmar and Thailand). It is often seen as a link between these two regions and their respective regional institutions: the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).[1] Fourteen sectors of cooperation have been identified by the member countries: trade, technology, energy, transport and communication, tourism, fisheries, agriculture, public health, poverty alleviation, counterterrorism, environment, culture, people-to-people contact, and climate change.[2]

In 2005, during the Eighth BIMSTEC ministerial meeting held in Dhaka, Thailand proposed that the sectoral theme of “traditional medicine” be expanded into a comprehensive area of cooperation on public health.[3] Some years later, in the 15th BIMSTEC Ministerial Meeting held in Kathmandu in 2017, a joint statement was issued recognising the importance of holistic public healthcare amongst the BIMSTEC member states and the need for establishing alliances. Since then, however, most intra-BIMSTEC collaborations have been centred on traditional medicine—which is the focus that had been set initially.[4]

COVID-19 Pandemic and the BIMSTEC Countries

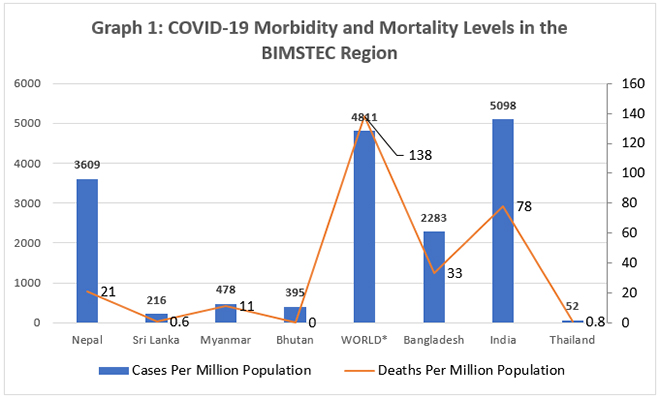

As Graph 1 shows, barring three countries—India, Bangladesh and Nepal—the BIMSTEC region has so far largely escaped the most devastating impact of the pandemic. Many countries in the region appear to be meeting with success in handling the pandemic; at the time of writing this brief, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and Bangladesh were no longer under lockdown. However, the economic costs of containing the pandemic have been immense.[5]

Although the current trend in terms of both COVID-19 cases and deaths across the BIMSTEC region is pointing downward, there is an alarming surge in Myanmar which the government is struggling to control.[6] Indeed, the South-East Asia Region (SEAR) of the World Health Organization (WHO)—which covers all the BIMSTEC members— continues to record the highest weekly increase in cumulative cases among all WHO regions. This is mostly because of the quantum of spread of infections in India. However, only Bangladesh has reported community transmission in the region.[7]

The pandemic has brought the focus back on public health. In their messages commemorating the 23rd anniversary of BIMSTEC’s establishment in June 2020, top leaders of the member countries expressed their commitment to working together and building better health resilience across the region. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared that India stands ready to share the country’s expertise, resources, capacities and knowledge with other countries in the region.[8] Some analysts have observed that the pandemic is also an opportunity for India to consolidate and strengthen both its Act East Policy (AEP) and Neighborhood First Policy (NFP), through crisis-time collaborations.[9]

WHO has called for stronger collective efforts and partnerships between member countries in the region to curtail the virus transmission; it is also urging countries to plan for efficient distribution of COVID-19 vaccines as soon as they are available, including creating “an expedited regulatory pathway for approval of new vaccine; a technical advisory group to recommend prioritization of risk groups; protocols on infection prevention and control measures to minimize exposure during immunization sessions; training plans for vaccine introduction; and monitoring systems to measure coverage, acceptability and disease surveillance”.[10]

To be sure, there are already existing collaborative projects that could contribute towards such efforts. The Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), for instance, launched the JIPMER-BIMSTEC Telemedicine Network (JBTN) in 2017 to strengthen links amongst premier medical institutions in the region. Considered one of the earliest initiatives to expand collaborations in modern medicine, it can potentially provide a platform to support the region’s COVID-19 response efforts.[11]

Beyond the immediate challenge of the pandemic, countries across the world, including those in the BIMSTEC region, are now healthier and wealthier than ever. In 1980, only 84 of every 100 children globally reached their fifth birthday, compared to 94 of every 100 in 2018. In 1980, a child born in a low-income country had a life expectancy of 52 years, which improved to 65 years in 2018.[12]In South Asia, life expectancy at birth was only 54 until 1980, improving to 69 in 2018. The corresponding improvement in life expectancy at birth within the East Asian region was 75 in 2018, an increase of 10 years since 1980.[13]

Improving skills, health, knowledge and resilience can help people become more productive, flexible and innovative, thereby finding more opportunities for social mobility. Investments in human capital, therefore, are core strategic decisions made by states, and not mere expenditure items within the social sector.[14]Biological threats in any country can pose both short-term and long-term risks to global health, international security and, above all, the global economy. This has been underlined by the COVID-19 pandemic. Communicable diseases know no borders, and there is a need to prioritise and enhance system-level capabilities to prevent, detect and rapidly respond to similar public health emergencies.[15]

Health remains as important in the second wave of the United Nations (UN) development goals—the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—as it was during the previous Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) era. It affects, and gets affected in turn, by all the other 16 SDGs, six of which deal with direct risk factors, eight with indirect determinants, and two with equity and means of implementation. Since ill health can undermine most, if not all, SDGs at the national and global level, SDG-3 on good health and well-being becomes one of the most important global goals.

Recent research has shown that people-to-people engagements can play a pivotal role in deepening the relations between BIMSTEC countries, around a ‘diplomacy for development’ focus.[16] Among the strategies that have been recommended as means to foster better integration are medical relief projects, research scholar exchange programmes, stronger institutional linkages with universities and other institutions of higher learning and research, joint research platforms, and capacity-building initiatives.[17]

The COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to wipe out years of progress the region has achieved towards SDGs, and it is widely believed that 2030 is no longer a realistic end-line for the global goals. The BIMSTEC region’s performance, in particular, will determine whether the world can achieve these goals, as it is home to more than one-fifth of the global population.[18] Although speculation around the revival of SAARC resulting in neglect of BIMSTEC was rife with the creation of a SAARC COVID-19 Emergency Fund, experts argue that there is higher coherence among BIMSTEC member states. Moreover, initiatives like the BIMSTEC Connectivity Master Plan will ensure that it remains a strategically important grouping.[19]

However, while both SAARC and ASEAN have launched deliberations to address the pandemic, BIMSTEC has yet to do the same.[20] Given this context, this brief attempts a comparative analysis of the human capital situation of the BIMSTEC region, paying specific attention to the health component, and makes broad recommendations to improve collaborative work in the health sector.

Health Components in Human Capital across BIMSTEC: A Comparative Analysis

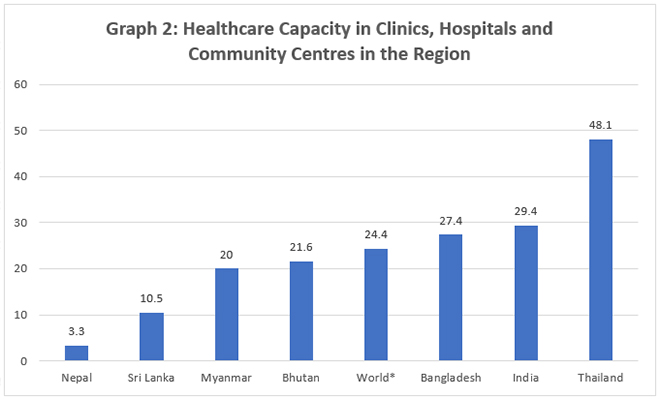

Health capacity in clinics, hospitals and community care centres is explored across BIMSTEC countries in Graph 2. ‘Healthcare capacity’ is operationally defined here as a combination of available human resources (e.g. doctors, nurses, midwives) for the broader healthcare system and the capacity of health facilities (e.g. availability of hospital beds). Sri Lanka fares significantly lower than the global average in this aspect, despite its health system being perceived as one of the better ones in the region.[21] Part of the challenge is the brain drain that remains a key factor weakening the health systems across South Asia. It had become such a binding constraint that the Government of India was forced to stop issuing the ‘No Obligation to Return to India’ (NORI) certificates required for Indian doctors to settle overseas.[22]

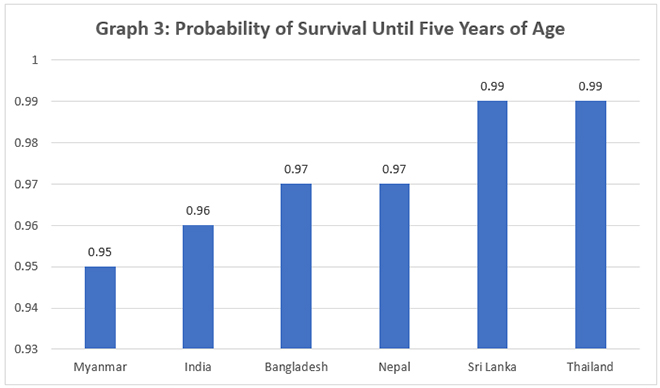

The Global Human Capital Index (HCI) was initiated by the World Bank and its partners to create a single cross-country metric for generating political awareness of the need for global action in social sectors such as health and education.[24]There are three health-related components within the HCI. First, according to the World Bank, the survival component reflects the fact that children born today must survive until the process of human capital accumulation through formal education can begin.[25] Survival is measured using the under-five mortality rate (See Graph 3). While almost all children survive from birth to school age in developed countries, preventable child deaths are still a crucial challenge in South Asia.

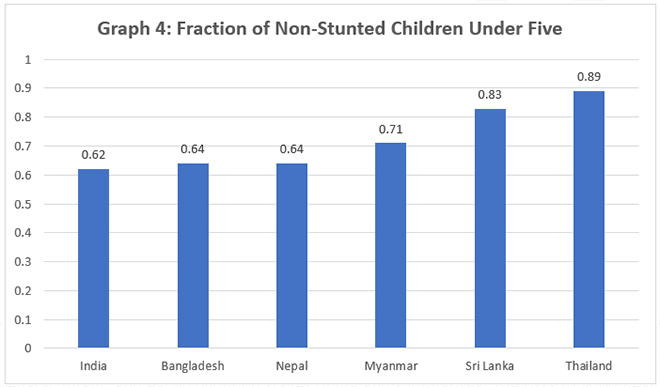

A second health-related component of human capital is the rate of stunting of children below five years old (See Graph 4). Stunting reflects the health environment experienced during the prenatal, infant, and early childhood stages of life and summarises “the risks to good health that children born today are likely to experience in their early years, with important consequences for health and well-being in adulthood.”[27] Here, “full health” is defined as absence of stunting. Compared with other BIMSTEC nations for which data is available, India fares the worst on this indicator. That the difference between the worst performer (India) and the best (Thailand) is a staggering 44 percent, underlines the health inequalities in the region and the need for immediate corrective action.

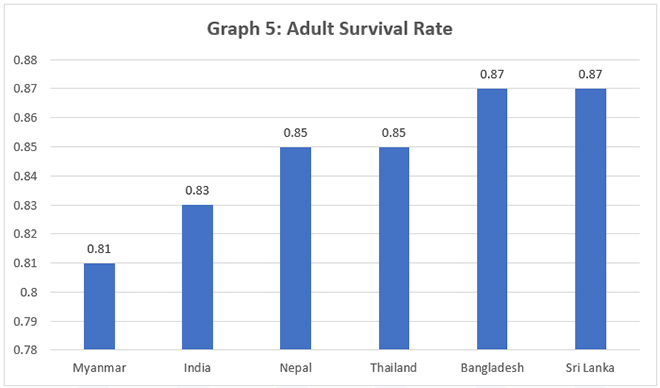

The last health-related component of human capital is the “adult survival rate,” defined as the proportion of 15-year-olds who will survive until age 60 (See Graph 5). This component reflects the range of health outcomes that a child may experience as an adult. In this context, “full health” is defined as 100-percent adult survival.[29] Amongst the BIMSTEC countries where data is available, India and Myanmar fare the worst. Using time series data between the years 2000 and 2017, the World Bank recently found that despite having many laggards, none of the countries from Asia figured among the top 5 percent of progress in adult survival rate.[30]

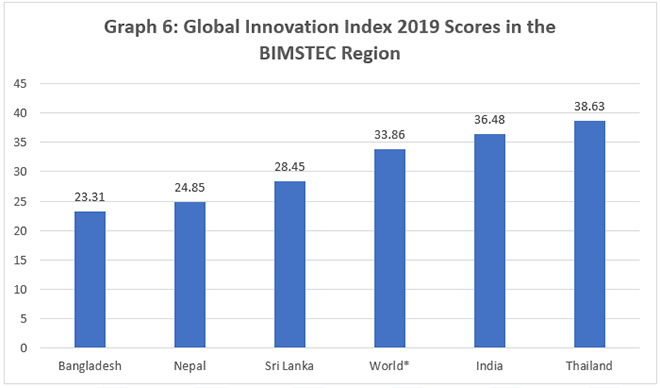

Overall, the health outcomes in the BIMSTEC region remain low, owing largely to bottlenecks within health systems. Moreover, the medical innovation landscape in the region leaves much to be desired. The Global Innovation Index 2019 focused on the future of global medical innovation and scored countries across a composite index, which pooled indicators across institutions, human capital and research, infrastructure, market sophistication, business sophistication, knowledge and technology outputs, and creative outputs. Only Thailand and India fared better than the global average (See Graph 6); both Bhutan and Myanmar remain absent from the global innovation landscape.[32]

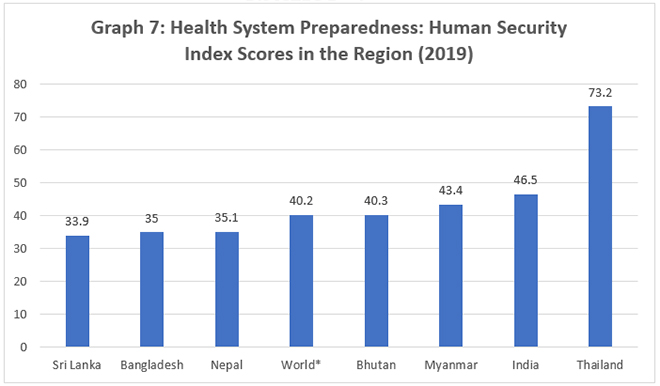

In exploring comparable data across BIMSTEC countries on “country preparedness for infectious disease outbreaks and high-consequence biological events like COVID-19,” data was taken from the Global Health Security Index 2019. On average, it was found that countries in the BIMSTEC region are poorly prepared for a globally catastrophic biological event (See Graph 7), including those “that could be caused by the international spread of a new or emerging pathogen or by the deliberate or accidental release of a dangerous or engineered agent or organism.”[34] The composite index of 34 indicators across six overarching categories scored each country on a scale of 0 to 100, wherein 100 represents the most favourable health-security conditions and 0 represents the least favourable. However, despite the gloomy scenario, BIMSTEC on average has done better so far than many other parts of the world in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion and Recommendations

An earlier paper by this author[36] observed that there are multiple areas within healthcare where BIMSTEC countries can learn from each other. These include telemedicine (Bhutan), monitoring of vital events through information technology (Bangladesh), the trial-and-error experimentation with the mother and child tracking system (India), the transformed district health information system (Bangladesh), often called a “silent revolution,” and the electronic medical records system (Sri Lanka).[37] Many of these possibilities have become even more relevant in the times of the COVID-19 pandemic and the long-term disruptions that it is causing social sectors.

The same 2017 paper observed[38] that while there have been a number of in-depth studies comparing the health systems of BRICS nations and offering valuable policy lessons, no such analyses have been undertaken for the BIMSTEC members. The situation remains the same in 2020. The COVID-19 crisis gives BIMSTEC members a collective opportunity to conduct and support comparative health system studies within the region. For a country like India, the stronger economies within BIMSTEC will provide valuable lessons for the future journey of its health sector and the relatively poorer members will offer lessons for the present. Additionally, platforms for cross-learning can be immensely beneficial for culturally and socially similar neighbouring countries to learn from each other’s successes and failures in health policy.

Considering the highly endemic nature of communicable diseases and the porous borders of BIMSTEC member states, this brief offers three recommendations. First, BIMSTEC must focus on collective action in the health arena and invest resources into developing public health as a regional public good. Under-investment in health is a problem across the region, and in addressing the issue, cross-border solidarity must be a key focus. This will contribute to regional as well as national resilience to adverse health events. Second, Thailand should take fresh initiatives as the BIMSTEC thematic lead to further public health as a sector of enhanced cooperation within the region. The country has made remarkable achievements in health and has relatively better health status as indicated by data, and could set the tone for a future health framework for regional cooperation. Third, BIMSTEC should host policy workshops and exchange programmes in the region. These efforts can culminate in the constitution of a dedicated public-health cadre within member countries, consisting of personnel for public-health management to help health systems overcome challenges such as COVID-19.

About the Author

Oommen C. Kurian is Senior Fellow, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.

Endnotes

[1] K. Yhome, “Twenty years of BIMSTEC: promoting regional cooperation and integration in the Bay of Bengal region” : edited by Prabir De, New Delhi, Knowledge World, 2018, pp. 292. ISBN 978-93-87324-35-0 (ebook). 2019, 373-376.

[2] Pratnashree Basu and Nilanjan Ghosh, “Breathing New Life into BIMSTEC: Challenges and Imperatives,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 243, April 2020, Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/research/breathing-new-life-into-bimstec-challenges-and-imperatives-65229/

[3] Soumya Bhowmick, “Reimagining BIMSTEC amidst the COVID-19 disaster”. ORF Expert Speak, 26 March 2020, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/reimagining-bimstec-amidst-the-covid-19-disaster-63736/

[4] Oommen C. Kurian, “Health policies of BIMSTEC states: The scope for cross-learning” ORF Issue Brief No. 211, November 2017, Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/research/health-policies-of-bimstec-states-the-scope-for-cross-learning/

[5] Peter Janssen, “Thailand’s Covid success turns economic failure”, The Asia Times, 14 August 2020, https://asiatimes.com/2020/08/thailands-covid-success-turns-economic-failure/

[6] World Health Organisation, “Weekly Situation Report”, Week 39, https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/searo/whe/coronavirus19/sear-weekly-reports/weekly-situation-report-week-39.pdf?sfvrsn=d87e089b_4

[7] “World Health Organisation, Weekly Situation Report”

[8] “BIMSTEC leaders pledge to collectively combat COVID-19 impact”, 6 June 2020, Bangladesh News, https://bdnews24.com/neighbours/2020/06/06/bimstec-leaders-pledge-to-collectively-combat-covid-19-impact

[9] Angshuman Choudhury and Ashutosh Nagda, “COVID-19 and the Rationale for Stronger Indian Links with Southeast Asia”, 13 May 2020, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, http://ipcs.org/comm_select.php?articleNo=5687

[10] WHO Press Release, “Collectively strengthen pandemic response; plan for COVID-19 vaccination: WHO”, 8 October 2020, https://www.who.int/southeastasia/news/detail/08-10-2020-collectively-strengthen-pandemic-response-plan-for-covid-19-vaccination-who

[11] Oommen C. Kurian, “Health policies of BIMSTEC states: The scope for cross-learning” ORF Issue Brief No. 211, November 2017, Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/research/health-policies-of-bimstec-states-the-scope-for-cross-learning/

[12]World Bank Group. World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work. World Bank, 2018.

[13]World Bank Group. World Bank Data. https://data.worldbank.org/

[14]World Bank Group. World development report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work. World Bank, 2018.

[15]Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health 2019 Global Health Security Index: building collective action and accountability. October, 2019. https://www.ghsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019-Global-Health-Security-Index.pdf

[16] C. Joshua Thomas, “Revitalising BIMSTEC through Cultural Connectivity from Northeast

India,” ORF Issue Brief No. 405, October 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

[17] C. Joshua Thomas, “Revitalising BIMSTEC through Cultural Connectivity from Northeast

India”

[18]https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/population-by-country/

[19] Nazia Hussain, “Impetus for SAARC Revival?”, RSIS Commentaries, 076-20, 14 September 2020, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, https://dr.ntu.edu.sg/bitstream/10356/143607/2/CO20076.pdf

[20] Anasua Basu Ray Chaudhury and Rohit Ranjan Rai, “Towards a Deliberative BIMSTEC,” Occasional Paper No. 263, August 2020, Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/research/towards-a-deliberative-bimstec/

[21] Dina Balabanova, Anne Mills, Lesong Conteh, Baktygul Akkazieva, Hailom Banteyerga, Umakant Dash, Lucy Gilson et al. “Good Health at Low Cost 25 years on: lessons for the future of health systems strengthening.” The Lancet 381, no. 9883, 2013, 2118-2133.

[22] Satyajit Das, “Rich countries must stop exploiting Asian nations’ health care”, 29 October 2019, Nikkie Asia, https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Rich-countries-must-stop-exploiting-Asian-nations-health-care

[23] Global Health Security Index: building collective action and accountability. October, 2019, accessed at https://www.ghsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019-Global-Health-Security-Index.pdf.

[24]The Human Capital Project. World development report 2019: The changing nature of work. World Bank, 2018.

[25]The Human Capital Project, World development report 2019

[26] World Bank Group. World Development Report 2019: The changing nature of work. The World Bank Group, 2018, https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/human-capital.

[27]World Bank Group. World Development Report 2019

[28] World Bank Group. World Development Report 2019

[29]World Bank Group. World Development Report 2019

[30] Zelalem Yilma Debebe, “What is an ambitious but realistic target for human capital progress?” , 29 January 2019, World Bank Blogs, https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/what-s-ambitious-realistic-target-human-capital-progress

[31] World Bank Group. World development report 2019: The changing nature of work. World Bank, 2018, https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/human-capital.

[32]Cornell University, INSEAD, and WIPO (2019); The Global Innovation Index 2019: Creating Healthy Lives—The Future of Medical Innovation, Ithaca, Fontainebleau, and Geneva.

[33] The Global Innovation Index 2019: Creating Healthy Lives—The Future of Medical Innovation, Ithaca, Fontainebleau, and Geneva, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_gii_2019.pdf

[34]Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health 2019 Global Health Security Index: building collective action and accountability. October, 2019. https://www.ghsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019-Global-Health-Security-Index.pdf

[35] Global Health Security Index: Building Collective Action and Accountability, October 2019. https://www.ghsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019-Global-Health-Security-Index.pdf.

[36]Oommen C. Kurian, “Health policies of BIMSTEC states: The scope for cross-learning” ORF Issue Brief No. 211, November 2017, Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/research/health-policies-of-bimstec-states-the-scope-for-cross-learning/

[37]A Decade of Public Health Achievements in WHO’s South-East Asia Region, World Health Organization, http://apps.searo.who.int/PDS_DOCS/B5003.pdf.

[38]Oommen C. Kurian, “Health policies of BIMSTEC states: The scope for cross-learning” ORF Issue Brief No. 211, November 2017, Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/research/health-policies-of-bimstec-states-the-scope-for-cross-learning/

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Oommen C. Kurian is Senior Fellow and Head of Health Initiative at ORF. He studies Indias health sector reforms within the broad context of the ...

Read More +