Introduction

The eight states of India’s North Eastern Region (NER) – Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura, and Sikkim – occupy a mere 8 percent of the country’s geographic area. Yet they are strategically important, as between them they share 5,300 km of international borders with the neighbouring countries of Nepal, Bhutan, China, Myanmar, and Bangladesh.[1] The NER is, however, at a logistical disadvantage as seven of the eight states are connected to the rest of India through only a narrow strip of land known as the Siliguri (or ‘chicken’s neck’) corridor.[a] Troubled, too, by recurring insurgencies, the states suffer poor connectivity. This has had an impact on the region, causing persistent underdevelopment and “alienation” from the Indian mainland. Around 28.5 percent of the NER’s population live below the poverty line—a proportion that is significantly higher than the all-India figure of 21.9 percent. The total road surface in the region is 33.7 percent, less than half the national average of 69 percent.[2]

The communities of the northeast are of the view that renewing old bonds of trade and connectivity with India’s neighbouring countries, can help them achieve prosperity.[3] After all, historically, India’s northeast had been the south-western track of the ancient Silk Route through which trade was conducted between India, south-west China, Tibet, Bhutan, and Burma (present-day Myanmar).[4] Indeed, in many parts of the world, sub-regional cooperation is today used as a strategy to stimulate growth and development in peripheral areas.[5]

Such a strategy hews with India’s overall foreign policy that seeks to enhance ties with the eastern neighbourhood. At the Shangri La Dialogue of 2018, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi eulogised the vision of Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR) by connecting India’s east and northeast with the country’s eastern neighbours via the Act East Policy.[6] The countries of Southeast Asia, under the rubric of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), occupy a central position in India’s Act East Policy, as India seeks opportunities for collaborative growth amidst China’s assertive rise in the Indian Ocean region. The ASEAN countries are suited for such engagements with India: there are no significant political disputes, the economies are on a growth trajectory, and there is also shared cultural heritage. Further, as the Act East Policy gradually morphs into ‘Act Indo-Pacific’,[7] with India’s expanding horizon for convergence and collaboration, the ASEAN countries – located at the junction of the Indian and Pacific Oceans – retain their centrality in India’s vision of the Indo-Pacific.[8]

Given ASEAN’s significance, the NER becomes important for India’s foreign policy manoeuvres as the only land ‘bridge’ between India and Southeast Asia. In recent times, New Delhi has prioritised improving trade and connectivity in the northeast, through a number of multimodal projects, linking the states themselves more closely while connecting them with the rest of India and the ASEAN nations.

However, road and railway projects are costly and carry environmental impacts, too. A more viable option could be to utilise the maze of inland waterways that intersperse the northeast to ferry cargo and passengers. It is relatively more environment-friendly and cheaper. Moreover, developing waterways that have links with seaports will provide the northeast the benefit of maritime trade, and improve its connectivity with the rest of India, Southeast Asia, and the wider Indo-Pacific. This report explores how inland waterways can be utilised to give India’s northeast states access to the sea.

The Importance of Bay of Bengal to the Northeast

In recent years, India has undertaken a number of connectivity projects in the NER. The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, for example, launched the ‘Special Accelerated Road Development Programme in North East’ in 2005, the scope of which has been enlarged occasionally since then[9] and is expected to be completed by the financial year 2023-24.[10] The government has also joined the Asian Highway (AH) network that seeks to connect 32 Asian countries, and one of whose principal routes – AH 1 – will traverse India and Bangladesh via the NER before extending into Southeast Asia. In the last four years, road and rail links in the NER have been growing apace, with INR 12,936.5 million being sanctioned for their development. Under various government schemes, 1,262 km of roads have been built during this period.[11] Several rail links across Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Mizoram, Tripura, and Assam have also been converted from meter-gauge to broad-gauge.[b] Infrastructural work to enhance air connectivity is also underway.[12]

One of the aims of the Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIM-EC) has also been to improve infrastructure and establish an appropriate regulatory framework to develop multimodal transportation between the NER and countries of East and Southeast Asia.[13] Once operational, the routes can benefit the northeast as most of these landlocked states, lacking easy access to sea ports, currently pay unduly high transportation costs. This deficiency also contributes to their further isolation.[14]

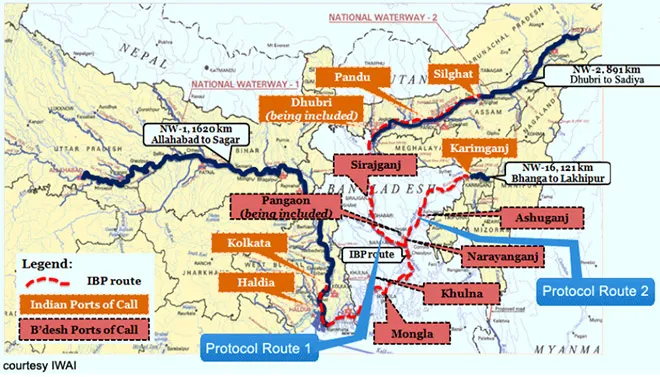

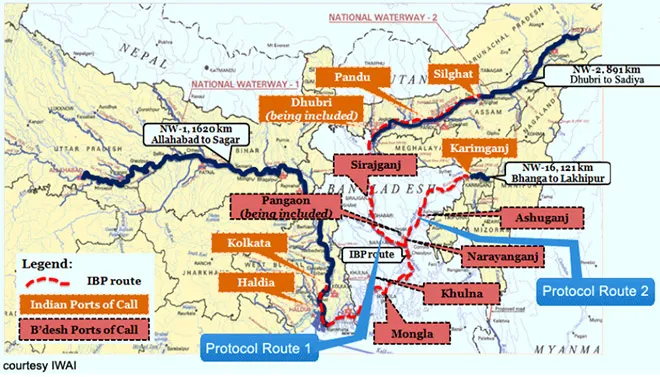

Many of the rivers that traverse the northeast, connect India with Bangladesh. Some of the old riverine routes between India and Bangladesh (when the latter was still East Bengal) have already been reactivated. Under the India-Bangladesh Protocol on Inland Water Transit and Trade (see Map 1) – first signed in 1972, and last renewed in 2015 with a clause for automatic renewal every five years – the two countries ferry goods using specified waterways passing through both territories.[c] There are five such waterways (or 10 routes, since the reciprocal route is regarded as separate).[d],[15] In 2018, India and Bangladesh agreed to develop Jogighopa in Assam’s Brahmaputra Valley as a hub/trans-shipment terminal for movement of cargo to Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland and Bhutan.[16] In 2020, Dhaka and New Delhi began operations on the ninth and 10th protocol routes – the Daudkandi (Bangladesh) to Sonamura (Tripura) route along the Gumti River – with the first-ever export consignment of cement reaching Tripura from Bangladesh.[17]

Map 1: The India-Bangladesh Protocol Route

Source: Assam Inland Water Transport Development Society

Source: Assam Inland Water Transport Development Society

Maritime or riverine connectivity has obvious advantages for the landlocked NER and strengthening this aspect of multimodal linkages can be a game-changer for the region. India’s northeast is crucial to its Act East Policy, and not merely because of its land bridge to Southeast Asia. It is also part of a maritime neighbourhood with Southeast Asia, connected by the Bay of Bengal. The Bay had once been a region unto itself – a fluid world linked through cultural and commercial ties.[18]

The northeast is criss-crossed by multiple rivers. It has an estimated 1,800 km of river routes navigable for steamers and large country boats. Cargo moved by these routes includes tea, cement, coal, fly ash, limestone, petroleum, bitumen, and food grains.[19] In Arunachal Pradesh, the rivers Lohit, Subansiri, Burhi Dihing, Noa Dihing, and Tirap are used for navigation by small country boats along those stretches where there are no rapids. The rivers Dhaleshwari, Sonai, Tuilianpui, and Chimtuipui in Mizoram are similarly used for navigation in convenient stretches. In Manipur, the Manipur River, along with its three main tributaries, the Iril, the Imphal, and the Thoubal—are used for transporting small quantities of merchandise by country boats. However, the main rivers of the region are the Brahmaputra, the Teesta, and the Barak. The Brahmaputra has several small river ports, along with more than 30 pairs of ferry ghats (crossing points). The Barak also has small ports at Karimganj, Badarpur, and Silchar and ferry services at several places.[20] While the Brahmaputra and the Barak flow into Bangladesh, coastal Myanmar is also part of the Barak river basin. Improving riverine linkages in the region thus opens up the NER to the entire Bay of Bengal.

Important sea lanes of communication traverse the Bay of Bengal and its adjoining Andaman Sea before merging into the wider waters of the Indo-Pacific via the Strait of Malacca. The need to preserve the autonomy of these shipping routes in the face of concerns posed by a rising China, coupled with the lure of the Bay’s vast hydrocarbon reserves, has attracted stakeholders to its waters in recent years. The Bay has emerged as a zone of competition and collaboration between its littoral countries and the global powers involved in the region such as Japan, the US, and Australia. If riverine connectivity is strengthened in the NER, enabling its ease of access to the Bay, such collaborations may prove beneficial for its development.

Indeed, the NER has already emerged as a focus area of development for Japan. Given China’s expanding footprint across the Indo-Pacific, its predatory economics and opacities in relation to its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a partnership has become geo-politically important for both Tokyo and New Delhi. Across the continental and maritime space of Eurasia and the Pacific, there is a growing sense of the need to push back against Beijing’s advances—this has resulted in informal groupings of countries as well as the bolstering of existing institutional mechanisms. The cooperation between India and Japan, while not borne entirely out of these compulsions, is nonetheless an expression of shared interests. Japan and India have found policy convergence in their respective visions of a free and open Indo-Pacific and established the “Japan-India Act East Forum" geared towards synergising India’s Act East policy with Japan’s “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy." For India, these undertakings form part of a definite policy shift from the earlier ‘Look East’ to ‘Act East’.[21]

As part of this initiative, India has already received assistance from Japan in improving road connectivity, power and water supply, and in skill development.[22] Some of the infrastructure projects to be undertaken by the Forum include improving National Highway 40 between Shillong and Dawki, National Highway 51 between Tura and Dalu—all four are towns in Meghalaya—and National Highway 54 between Aizawl and Tuipang in Mizoram.[23] In collaboration with the Asian Development Bank (ADB), New Delhi and Tokyo are also exploring the possibility of a corridor linking Gelephu, on the Assam-Bhutan border, and Dalu, on the Meghalaya-Bangladesh border.[24] These routes will contribute to multimodal linkages in the NER, in turn facilitating maritime connectivity. Therefore, as India strives to utilise the Bay as a stepping stone into the Indo-Pacific, the NER, with a well-connected network of ports and waterways, has the potential to become an important part of the growth story.

Exploring Port Connectivity with the Northeastern Hinterland

To ensure the NER has easy access to the sea, it is important to identify ports in India as well as in the bordering countries of Bangladesh and Myanmar which can be the immediate nodal points of sea connectivity. Three such ports are particularly important: Kolkata-Haldia in India, Chittagong in Bangladesh, and Sittwe in Myanmar. (Kolkata Port in this text refers to the Kolkata Dock System, and Haldia is the Haldia Dock Complex. Both are under the Kolkata Port Trust.) These ports, although riverine, have easy access to the sea, and if linked with the NER through multimodal connectivity will prove useful in enhancing the NER’s connectivity not only with Southeast Asia but also with the rest of India. It is thus worth assessing their potential.

The Kolkata port under the Kolkata Port Trust is situated on the River Hooghly in West Bengal and is geographically India’s closest port to the Northeast. Even so, it is still around 700 km from the border of Sikkim and over 1,100 km from the Assam border. The port, 223 km from the sea, is highly profitable, boasting hinterland connectivity with eastern India, Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh, and if better connected to the NER would be beneficial for those states as well. Using the India-Bangladesh protocol routes, particularly the ones that navigate the River Barak (National Waterway 16) can significantly reduce the port’s distance from the NER.[e] Developing the river route from Dhulian in West Bengal to Rajshahi, Aricha and Dhaka in Bangladesh also reduces distance and travel time between Kolkata and the NER.[25] During British rule, the Brahmaputra and Barak-Surma rivers[f] were used extensively for transport and trade between the NER and Kolkata.[26]

In 2018, Badarpur in Assam’s Barak Valley was declared an ‘extended port of call’ of the bigger town of Karimganj, the two lying about 25 km apart along the Barak River. Reciprocally, in Bangladesh, Ghorasal was identified as an extended port of call of Ashuganj. An extension of protocol routes through Bangladesh from Kolkata to Silchar in Assam’s Barak Valley – has also been proposed by India. The declaration of additional ports of call and extensions of protocol routes are expected to substantially augment the cargo transported through inland waterways. The northeastern states could get directly connected to the ports of Kolkata-Haldia and Mongla in Bangladesh through waterways. This would also facilitate the movement of cargo exported to and imported from Bangladesh, and reduce logistics costs.[27]

Unfortunately, despite the high functionality of the Kolkata Port and its robust road and rail connectivity,[28] it has a low draft of 7.2 meters and thus cannot accommodate large vessels. It also needs dredging, making navigation more difficult for larger vessels.[29] The Haldia Dock Complex, located 75 km from the sea,[30] has the same problem. To overcome this, India is considering building two deep-sea ports at Tajpur and Sagar in West Bengal. Once completed, these ports too, will offer the NER access to the sea.

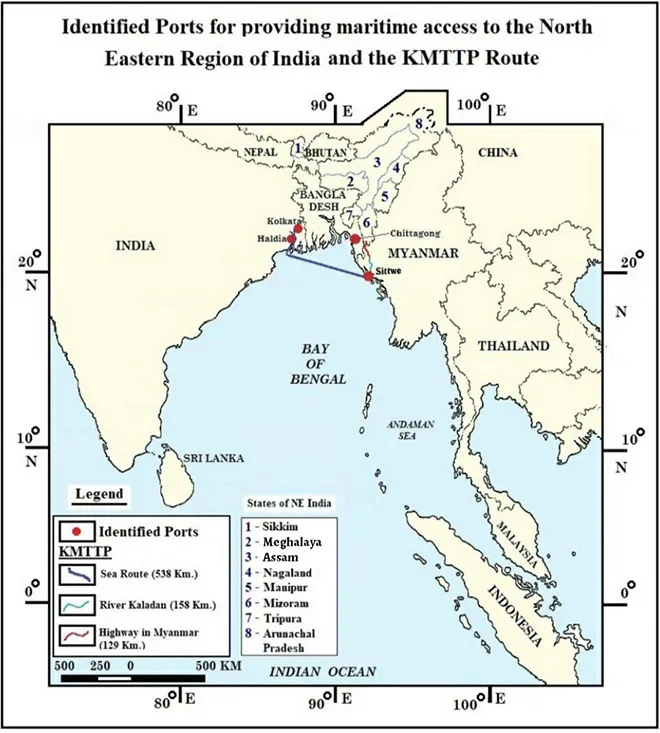

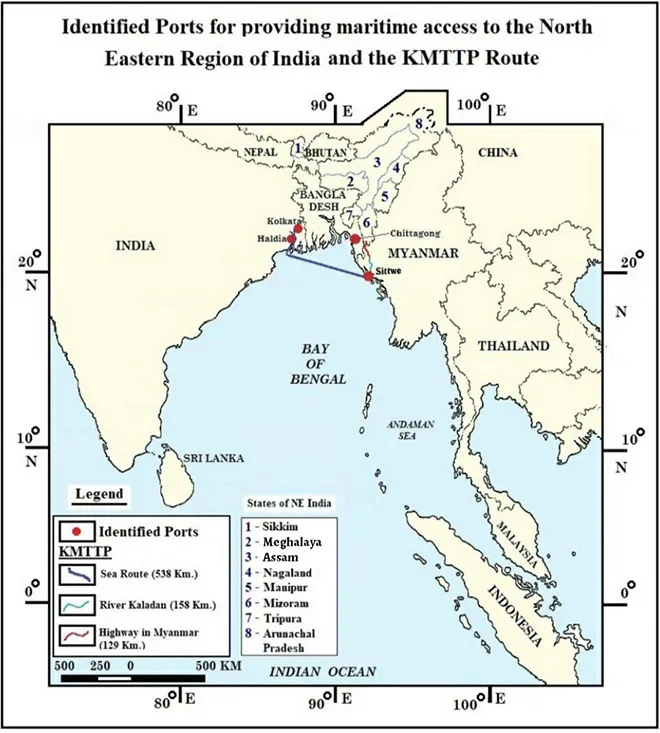

Notwithstanding Haldia’s limitations, India has also sought to connect it to Mizoram through Sittwe Port in Myanmar’s Rakhine state, which is also situated at the mouth of the Kaladan River as it enters the Bay. The Kaladan Multi-modal Transit Transport Project (KMMTTP) envisions road transport of goods from Mizoram to Paletwa in Myanmar, and thereafter river transport along the Kaladan River to Sittwe, and finally, from Sittwe to Haldia by sea through the coastal shipping route.

The Sittwe port and Inland Water Transport Paletwa jetty became operational in April 2107.[31] The countries had agreed to the project in 2008, but it has been much delayed.[32],[33] The Sittwe port finally became operational in March 2021,[34] and direct access from Kolkata to Sittwe now takes about two days.

Map 2: KMMTTP Route and identified ports for providing maritime access to India’s northeast

Source: Created by Jaya Thakur, Junior Fellow, ORF, Kolkata.

Source: Created by Jaya Thakur, Junior Fellow, ORF, Kolkata.

Geopolitically, Sittwe port, financed by India, stands as a counterbalance to the Kyaukpyu port[35] in Myanmar, built by China and part of the BRI. Myanmar is India’s immediate neighbour from Southeast Asia and is also a part of ASEAN, and thus important to India’s Act East Policy. The Sittwe project, along with the 1,360-km trilateral highway being built by India, Myanmar and Thailand, extending from Moreh, on Manipur’s eastern border, to Mae Sot in Thailand, cutting across Myanmar, is also expected to boost trade in the ASEAN-India Free Trade Area. New Delhi has proposed that the highway be extended to Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Bangladesh is also keen to join the project.[36]

With the KMMTTP proving to be a difficult undertaking, the Chittagong Port Authority in Bangladesh has floated the idea of Chittagong as an alternative to Sittwe to transfer goods to the NER via Ashuganj.[37] The Ashuganj river port is close to Tripura, and has been used to ferry rice to that state. It is expected to become even more profitable with the operationalisation of the Agartala–Akhaura (in Bangladesh) rail link. Transhipment from Ashuganj to the NER of goods coming from ports such as Chittagong using inland waterways will help boost the economies of both countries.[38]

The Chittagong port is the principal seaport of Bangladesh and ranks 76th amongst the 100 busiest ports of the world. It is situated on the Karnafuli River, 15-16 km from the sea. The Coastal Shipping Agreement between India and Bangladesh, signed in 2015, has since been expanded to allow India to use the ports of Chittagong and Mongla to deliver goods to the NER.[g],[39] The transit route of the Haldia dock through Bangladesh to Assam can be linked to Chittagong port and the connectivity extended to the southern tip of Tripura. This will be yet another link for the NER with the rest of India, and will facilitate expanding connectivity with Southeast Asia.[40]

The Chittagong Port, however, faces challenges including congestion. Being a riverine port, it also depends on tidal currents for operations. A Bay container terminal is being constructed by the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA) International—this will increase the port’s handling capacity.[41]

Coastal shipping agreements have been reached between India and Bangladesh, India and Myanmar,[42] and between Myanmar and Thailand. If Bangladesh and Myanmar come to a similar agreement and the entire coastline is linked for coastal shipping, the NER would reap substantial benefits. However, more infrastructural development is required if NER is to become an active participant in trade instead of remaining a mere conduit.

Opportunities in the Northeast

The advantage of augmenting connectivity of the NER is two-fold: it will enhance the socio-economic conditions in the region, and increase the foreign policy outreach to the east of the country. Establishing multi-modal connectivity in the north eastern region, with an emphasis on improved trade relations with emerging economies like Myanmar and Bangladesh, will bolster the economic growth of the region.[43]

Indeed, as Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has noted, the NER “has the potential to become the growth engine for India.”[44] So far, however, though India has committed around USD700-800 million for the development of trade in the northeast, there has been little productive change in the region. The region’s economies have hardly improved, despite the many projects that have been taken up over the years in the NER such as the Trilateral Highway, the Indo-Bangla Protocol Routes, improving air connectivity in the region under the UDAN (Ude Deshka Aam Nagrik) scheme, and dredging the Brahmaputra River.[45]

Despite its resources, the NER has rarely been perceived as a natural destination for investment due to the region’s thin population, difficult terrain, fragile ecology and, until recently, volatile political environment.[46] Better connectivity, it is argued, would compensate for these shortcomings and thereby improve trade and economic exchanges with neighbouring countries. Empowering local administrations, alongside enhancing regional markets, can promote peace and stability by encouraging collaboration and cooperation with trans-border ethnic groups.[47] Multimodal linkages can tap into existing overland routes of hinterland connectivity by improving linkages which are poorly developed as well as laying new road networks. Enhancing hinterland connectivity would facilitate linking these local road and river networks to the rest of India on the one hand, and with countries in the east, on the other. For a resource-rich region like the NER, functional hinterland connectivity with maritime access will boost trade in both agricultural produce and manufactured goods.

Despite being a storehouse of resources,[h] yields are low in the NER due to the use of archaic agricultural and other resource-extraction techniques.[48] Improved telecommunications and digital links in the region, alongside better waterways, road and rail connectivity would ensure easy transfer of technical knowledge, expertise and whatever else is needed to maximise outbound trade from the region. Investments in the NER ought to also focus on quality control and better marketing of regional agro-based products. Enhanced connectivity will also expand employment opportunities, which in turn would reduce the appeal of the remaining insurgent outfits in the region.[49]

Security Challenges to Connectivity

For decades since India’s independence, development in the NER has taken a backseat primarily due to the region’s perceived strategic and security-related risks. Coupled with the periodic insurgencies that have plagued the region for decades, this has resulted in limited infrastructural progress in the region, despite the disbursal of considerable funds by the Indian government and the projects that have been undertaken, albeit intermittently. The NER’s porous international borders with Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Myanmar, which make it difficult to track smuggling, drug trafficking, and undocumented migration, are enduring challenges. Healthy and flourishing trade is possible only if the law-and-order situation in these states improves.

There are also longstanding border disputes between many of the states, which have led to road blockades (and worse) by one state or another, as seen recently in the case of Assam-Mizoram[50] and Assam-Nagaland.[51] This has not only impeded development but also weakened any incentive for multilateral or bilateral cooperation. The result is persistent instability that jeopardises bilateral and multilateral initiatives, creates execution delays for projects, and hinders prospects of external investments.

The intra-region conflicts need to be resolved at the earliest for India to harness the NER’s potential. The Naga political conflict, for example, spans four states, three of which border Myanmar—[i],[52] a country of great strategic importance to India’s Bay of Bengal agenda. This importance has only increased after China built the Kyaukpyu port in Myanmar.[53] The Rohingya crisis is another area of concern. The trafficking of Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazaar to other Southeast Asian countries poses a grave threat to the security of the region. The Bangladesh government has identified the border with Myanmar as a key entry point of illegal drugs into the country.[54]

To be sure, there has been a greater degree of stability in more recent years. The Bodo Accord of 2019, the third reached with insurgents of the Bodo tribe in Assam[j]— hopefully marks the end of the Bodo insurgency and the beginning of peace-making in the lower Assam region. Further, the surrender of five militant groups in Assam’s Karbi Anglong district (which lies between the Brahmaputra and Barak Valleys), is also an indication of improving internal security. However, tensions remain in the region, and insurgent groups are still spread out in Nagaland, Manipur, and Assam. There is still a likelihood of these conflicts adversely impacting the development of these states. What would help connectivity channels to operate unhindered are measures such as effective border patrolling, close scrutiny of cross-border movements, and intelligence-sharing.

Looking Ahead: Strengthening Waterways from the NER to the Bay

To keep the inland waterways of the NER operating smoothly, it is important to maintain the draft and width necessary for year-round navigation. Sedimentation in the waterways leads to frequent grounding of vessels, which raises their fuel costs. It also makes the channels unsafe and unreliable. The appearance of unpredictable shoal along the riverbed is also a hindrance for vessels. Improved irrigation practices, along with periodic dredging, can be considered to ensure better flow in the rivers. It is also important to ensure night navigational facilities along the river routes. Such facilities are seldom available for Indian ships plying Bangladeshi routes.[55] Inclusive development of inland waterways will provide greater employment to the people of the NER.

Another problem is the dearth of vessels for inland water transport in east and northeast India. Those used are mostly owned by the Central Inland Waterway Transport Corporation, the West Bengal Transport Corporation, Vivada Transportation Corporation, and the Inland Waterways Transport and Development Authority.[56] Insufficiency of vessels may prove to be a constraint in the growth of sub-regional connectivity. Naturally, the number of vessels can only increase if there is a corresponding rise in demand for such transport.

Besides trade, the riverine routes can be used to bolster tourism in the NER, which would contribute significantly to its economy. A Memorandum of Understanding between India and Bangladesh on operating cross-border river cruises along the coastal and protocol routes[57] was signed in 2015. In 2018, a Standard Operating Procedure for movement of passengers and cruise vessels on inland protocol routes and coastal shipping routes was also finalised. The river cruise route is likely to be Kolkata–Dhaka-Guwahati–Jorhat and back.[58] If this protocol route is extended further into the NER and connected as well to rivers in Nepal, Bhutan and Myanmar, tourism in the region will receive a boost.[59]

Above all, a tripartite multimodal agreement between India, Bangladesh and Myanmar is critical to realise such aspirations. Though India has begun to augment development in the NER in keeping with its Act East policy, a lot remains to be done. As noted earlier in the report, the involvement of Japan in the NER’s development assumes importance.

The NER faces myriad challenges in terms of geography, socio-economic conditions, and political stability. Nevertheless, the revival and expansion of inland waterways, and linking them across national borders using multimodal networks, promises to transform the NER. Improvements in the NER will hinge upon the sustainability of the various policy projects agreed to, along with a distinct focus on utilising riverine routes for maritime access.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this report are drawn from points made by speakers during the session on – ‘Bay of Bengal as Stepping Stone for the Wider Indo-Pacific’ at ORF’s International Webinar on Exploring Connectivity in the Bay of Bengal Region: Importance of India’s North East, held on 6 March 2021. The session was chaired by Harsh V. Pant, Head, Strategic Studies, ORF, New Delhi, India. The speakers in the session were the following:

Alex Waterman, Research Fellow in Security, Terrorism & Insurgency, University of Leeds, England.

Gautam Mukhopadhyay, Ambassador (Retd.), Senior Visiting Fellow, Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi, India.

Madhuchanda Ghosh, Assistant Professor, Presidency University, Kolkata, India

Indrani Bagchi, Diplomatic Editor, The Times of India, New Delhi, India.

Masami Ishida, Professor, Dept. of International Development Studies, Bio-resource College, Nihon University, Japan.

About the Authors

Sohini Bose is Junior Fellow, and Pratnashree Basu is Associate Fellow at ORF, Kolkata

(Additional research by Vaishnavi Bhaskar, Research Intern at ORF, Kolkata)

Endnotes

[a] Sikkim is west of Siliguri, and not connected to India through the 'chicken neck'. Historically, too, Sikkim was not counted among the North Eastern states (which were 'seven sisters') until 2002.

[b] The distance between the inner sides of two tracks on any railway route is known as railway gauge. In a meter gauge the distance between the two tracks is 1,000 mm and it costs less. In a broad gauge, in contrast, there is a distance of 1676 mm between the two tracks—it offers more stability and is better than thinner gauges.

[c] Only Indian and Bangladeshi vessels are allowed to use them.

[d] The routes connect West Bengal to Bangladesh, Tripura to Bangladesh, West Bengal to Assam’s Brahmaputra Valley, West Bengal to Assam’s Barak Valley, and Assam’s Brahmaputra Valley to its Barak Valley. The last three all pass through Bangladesh.

[e] However, these routes are seasonal, and alternative rail and road arrangements are also necessary.

[f] The Barak River is called the Surma in Bangladesh.

[g] Bangladesh has allowed the use of the following routes: Chittagong/Mongla to Agartala (Tripura), Chittagong/Mongla to Dawki (Meghalaya) and Chittagong/Mongla to Sutarkandi (Assam).

[h] The main agricultural products of the NER are tea, rice, bamboo, black rice, pork and ginger. Some areas also have oil and mineral reserves.

[i] Nagaland, Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh (all three bordering Myanmar) and Assam.

[j] Earlier accords were reached in 1993 and 2003, but some sections of the Bodo insurgents had rejected them. The Bodos are the principal tribe in four districts of lower Assam who launched a violent movement for a separate state in the late 1980s.

[1]Anil Wadhwa, “The North East is key for India’s ties with Asean,” LiveMint, March 9, 2018.

[2] Takema Sakamoto, “India-Japan Partnership for Economic Development in the Northeast”, Japan International Cooperation Agency, March 20, 2018.

[3]Pratim Ranjan Bose, “Connectivity is No Panacea for an Unprepared Northeast India,” Strategic Analysis 43, no.4 (June 9, 2019): 336.

[4] Madhuri Saikia, “Trade and Urbanisation- India’s North East in the ancient Silk Route,” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention 9, no. 8 (August 2020): 2.

[5]Anasua Basu Ray Chaudhury, “Connectivity and Sub-regional cooperation in the East of South Asia: Importance of India’s North-East Revisited,” in Connecting Nations: Politico-Cultural Mapping of India and South East Asia, ed. Achintya Kumar Dutta and Anasua Basu Ray Chaudhury (Delhi: Primus Books, 2019), 163.

[6] Government of India, “Prime Minister’s Keynote Address at Shangri La Dialogue,” Media Centre, Ministry of External Affairs, June 1, 2018.

[7] Prabir De, “India’s Act East policy is slowly becoming Act Indo-Pacific policy under Modi government,” The Print, March 27, 2020.

[8] Government of India, “Prime Minister’s Keynote Address at Shangri La Dialogue”

[9] Government of India, “Brief Status of SARDP-NE,” Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region, March 2012.

[10] Anisha Dutta, “Funding for NE road development increased,” Hindustan Times, October 7, 2020.

[11]Government of India, “Road and rail connectivity in North Eastern Region”, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of the Development of the North-East Region, July 17, 2019.

[12] Government of India, “Road and rail connectivity in North Eastern Region”

[13]Anasua Basu Ray Chaudhury, “Connectivity and Sub-regional cooperation in the East of South Asia: Importance of India’s North-East Revisited,”159

[14] Anasua Basu Ray Chaudhury, “Connectivity and Sub-regional cooperation in the East of South Asia: Importance of India’s North-East Revisited,” 160

[15] Government of India, “Second addendum to the protocol on inland water transit and trade between the government of the republic of India and the government of the people’s republic of Bangladesh,” Ministry of Shipping.

[16] Government of India, “India and Bangladesh Sign Agreements for Enhancing Inland and Coastal Waterways Connectivity”, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Shipping and Waterways, October 25, 2018.

[17]Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury, “India, Bangladesh launch new initiative to connect landlocked North East”, The Economic Times, September 03, 2020.

[18] Varun Nayar, “Reframing Migration: A Conversation With Historian Sunil Amrith,” Pacific Standard, December 1, 2017.

[19] Government of India, “Inland Waterways in NER”, Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region.

[20] Government of India, “Inland Waterways in NER”

[21]Rajeev Bhatia, “Japan in India’s North East”, Gateway House, August 22, 2019.

[22]“The North East is key for India’s ties with Asean”

[23]Aroonim Bhuyan, “Why Northeast matters for India-Japan collaboration in Indo-Pacific”, Business Standard, October 31, 2018.

[24] “Why Northeast matters for India-Japan collaboration in Indo-Pacific”

[25]Anasua Basu Ray Chaudhury, Pratnashree Basu, Sreeparna Banerjee and Sohini Bose, “India’s Maritime Connectivity: Importance of the Bay of Bengal,” Observer Research Foundation, March 2018, 79.

[26] Government of India, Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region.

[27]Government of India, “India and Bangladesh Sign Agreements for Enhancing Inland and Coastal Waterways Connectivity,” Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Shipping and Waterways, October 25, 2018.

[28] “India’s Maritime Connectivity: Importance of the Bay of Bengal,” 20

[29] “India’s Maritime Connectivity: Importance of the Bay of Bengal,” 13

[30] “India’s Maritime Connectivity: Importance of the Bay of Bengal,” 17

[31] “India’s Maritime Connectivity: Importance of the Bay of Bengal,” 82

[32] “India, Myanmar working to operationaliseSittwe port in early 2021,” Hindustan Times, October 1, 2020.

[33]Manoj Anand, “Steps on to complete India-Mayanamr-Thailand Trilateral Highways”, Deccan Chronicle, October 6, 2020.

[34]Elizabeth Roche, “Sittwe Port in Myanmar is ready for operations: Mandaviya”, LiveMint, March 8, 2021.

[35]C Christine Fair, “As Smart as Sittwe: Going North-East by South-East”, Firstpost, April 19, 2019.

[36]Aakriti Sharma, “Bangladesh Keen To Join India’s ‘Trilateral Highway’ That Includes Myanmar & Thailand”, The Eurasian Times, December 19, 2020.

[37] “India’s Maritime Connectivity: Importance of the Bay of Bengal,” 46

[38] “India’s Maritime Connectivity: Importance of the Bay of Bengal,” 73

[39] Government of India, “India and Bangladesh Sign Agreements for Enhancing Inland and Coastal Waterways Connectivity”, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Shipping and Waterways, October 25, 2018.

[40] “India’s Maritime Connectivity: Importance of the Bay of Bengal,” 73

[41] “Bangladesh Port Boom Begins,” Port Strategy, November 27, 2020.

[42]“India’s coastal shipping agreement with Myanmar,” Maritime Gateway, October 7, 2020.

[43]Prakash Tulsiani, “Uncorking The Logistic Competencies Of India's North-East”, Business World, August 4, 2018.

[44]“Northeast has potential to become India’s growth engine: PM Modi”, Hindustan Times, July 23, 2020.

[45]K. K. Dwivedi, “Assam’s story: Making Geography History by Acting East”, Economic Times, March 15, 2021.

[46]Pratim Ranjan Bose, “Connectivity may not put North-East India on the map”, Business Line, May 17, 2019.

[47]ShristiPukhrem, “The Significance of Connectivity in India-Myanmar Relations”, Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, July 6, 2012.

[48]Pratim Ranjan Bose, “Connectivity may not put North-East India on the map”

[49]Shristi Pukhrem, “The Significance of Connectivity in India-Myanmar Relations”, Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, July 6, 2012.

[50]Karishma Hasnat, “Central forces to be deployed as Assam-Mizoram border issue remains on the boil”, The Print, November 4, 2020.

[51]Alice Yhoshü, “Assam-Nagaland border row: Deputy commissioners trying to resolve tensions”, Hindustan Times, November 22, 2020.

[52]Vikas Kumar, “India Cannot Forge Bonds With Southeast Asia Ignoring Issues of Its Northeast Region”, The Wire, February 11, 2021.

[53]Sutirtho Patranobis, “Too close for comfort: China to build port in Myanmar, 3rd in India’s vicinity”, Hindustan Times, November 9, 2018.

[54]Sreeparna Banerjee, “The Rohingya Crisis and its Impact on Bangladesh-Myanmar Relations”, Observer Research Foundation, August 26, 2020.

[55] “India’s Maritime Connectivity: Importance of the Bay of Bengal,”76

[56]“India’s Maritime Connectivity: Importance of the Bay of Bengal,” 77

[57]“The Memorandum of Understanding on the Coastal and Protocol route between the Ministry of Shipping, Government of Republic of India and The Ministry of Shipping, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh,” November 16, 2015.

[58]Government of India, “India and Bangladesh Sign Agreements for Enhancing Inland and Coastal Waterways Connectivity”, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Shipping and Waterways, October 25, 2018.

[59] “India’s Maritime Connectivity: Importance of the Bay of Bengal,” 79

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV