-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Terri Chapman, “How the COVID-19 Pandemic Exposes the Frailty of Social Protection in the US,” ORF Issue Brief No. 352, April 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

Even the most sceptical of welfarism in the United States (US) agree that in the ongoing pandemic of COVID-19, an infectious disease caused by the novel coronavirus or SARS-CoV-2, sweeping measures to support the people are imperative. The Trump administration in mid-March ordered a relief package to waive the costs of coronavirus testing even for those who are uninsured.[1]Moreover, in an attempt to mitigate the economic impact of the crisis, lawmakers are looking to provide financial support to companies, as well as direct cash transfers to individuals.[2]

More than these emergency measures, however, the current public health crisis highlights the need for longer-term social protection reforms. After all, basic social protections such as health insurance, unemployment protection, guaranteed minimum incomes, paid parental leave, childcare support, and pensions all help to mitigate risks for individuals and households across the life cycle. In turn, as individuals are protected, the economy and society become more resilient.

At the time of writing, the US had the most number of COVID-19 infections in the world, at 163,199 of the total 827,419 cases in 205 countries and territories.[3]Compared to the 10 OECD countries with the highest per-capita GDPs, the US consistently underprovides, in an alarming degree, basic social protections.[4]

Rich country, no Universal Health Coverage

The American welfare system is unique in that it relies heavily on private markets. There is significant geographic variation in benefits and protections across the country, and it is underpinned by an idea of the “deserving poor”. This in turn has led to skewed benefits towards the elderly and increasingly towards children, but away from the working age population.[5] The unique characteristics of the fragmented American welfare system have led to a less comprehensive and less generous system overall, when compared to other rich countries.[6]

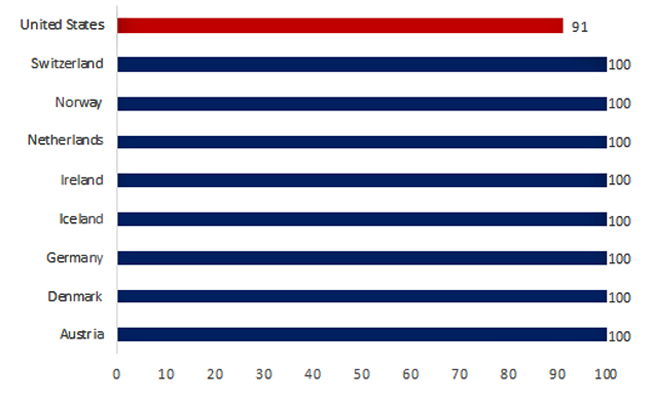

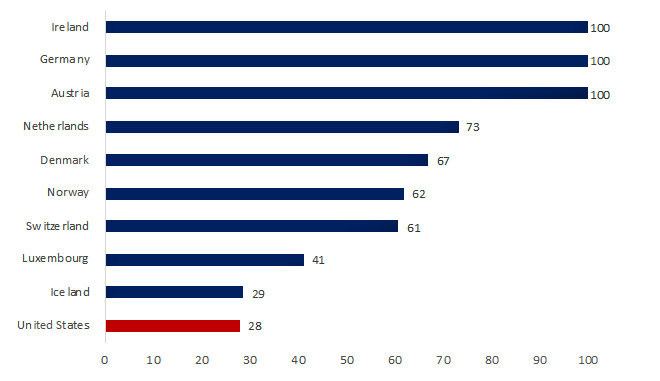

A fundamental element of a robust social protection system is health insurance; as of 2018, nine percent of the US population do not have some form of coverage.[7] The failings of the US’ safety nets do not end there. Of the unemployed, only 28 percent are receiving unemployment benefits.[8] For those who fall below the minimum standard of living, the guaranteed minimum income (GMI) is a mere six percent of the median wage, and far below the poverty threshold.[a] For new parents, paid leave is not mandated, and childcare costs amount to nearly one-third of household income.[9] In their old age, Americans can expect little financial support, with most people over 65 depending on wages from work as their main source of income.[10]

To be sure, the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—better known as ‘Obama Care’—enacted in 2010 led to an additional 20 million Americans being covered by health insurance.[11] Since Trump assumed office, however, efforts to dismantle the ACA by his administration have led to declines in the insured population.[12]Between 2016 and 2018, the number of uninsured increased by 1.2 million people;[13] indeed, the US is one of the few rich countries in the world without universal health coverage. Of those who are insured, 29 percent are underinsured.[14] The share of underinsured increased between 2014 and 2018.[b]

Cost remains a key barrier: nearly half (45 percent) of those who were uninsured in 2018 cite the cost of coverage as the reason they do not have insurance.[15]For those who are underinsured, 41 percent report forgoing needed medical treatment because of the cost.[16] Healthcare costs in the US are considerably higher than in other comparable countries, with average per-capita annual spending of $10,583.[17] And these costs are rising quickly. Between 1970 and 2018, per-capita costs increased 31-fold.[18] The share of public and private health spending as a share of GDP increased from 6.9 percent to 17.7 percent of GDP during the same period.[19] For many Americans who receive health insurance through their employer, increases in healthcare costs have translated to lower wage increases. Moreover, costs for individuals have risen, as 11 percent of health expenditure in the US is out-of-pocket. This makes medical debt a major challenge for the uninsured and the underinsured. Over half (53 percent) of uninsured individuals reported difficulty paying for a medical bill in the last year.[20]

Figure 1: Percent of the Population with Public and/or Private Health Insurance

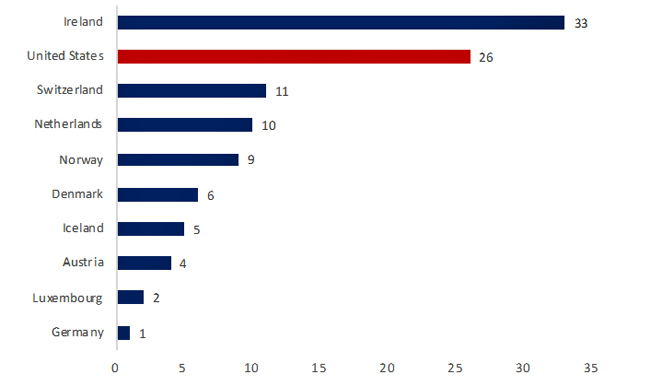

Unemployment benefits can be in the form of insurance, assistance, employment guarantees, and/or minimum income guarantees.[22] There is a strong economic case for unemployment benefits, as they ensure that those who may have lost their jobs are able to meet their needs without depleting their assets.[23] Adequate income support reduces income insecurity and the risk of slipping into poverty.[24] Moreover, it helps the unemployed avoid the trap of having to resort to taking jobs for which they are overqualified, and in the longer-term this increases productivity.[25] During periods of recession, unemployment protections help to steady the economy. In the United States, however, only 28 percent of those who are unemployed are receiving such assistance.[26] In contrast, other countries like Ireland, Germany and Austria have universal coverage, and Switzerland, Norway, Denmark and Netherlands have coverage above 50 percent.

Figure 2: Percent of Unemployed Receiving Unemployment Benefits

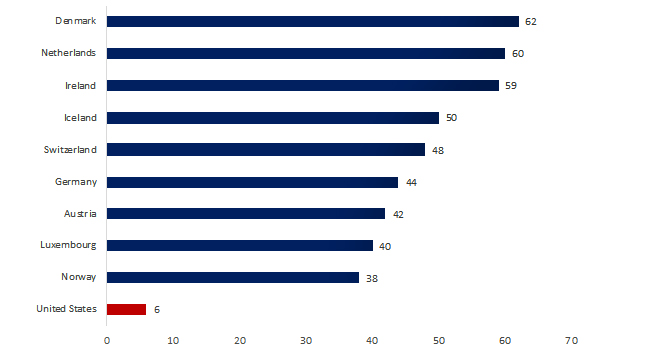

Guaranteed Minimum Income (GMI) is a social protection measure that ensures individuals or households have sufficient income to achieve a minimum standard of living. Income transfers are available to those who fall below a determined income level and meet certain eligibility criteria.[28] Figure 3 compares the GMI amount received by surveyed jobless families as a share of the median disposable income in that country.[29] In many European countries the poverty threshold is defined by a fixed percent of the median income (usually 60 percent). Figure 3 therefore shows the gap between the income of GMI recipients and the poverty line. In almost all countries, GMI alone is not sufficient for people to move out of poverty. This is especially true in the United States, where the GMI amount is just six percent of the median disposable income for a single person with no children.[30]

Figure 3: Guaranteed Minimum Income Amount as a Share of Median Disposable Income

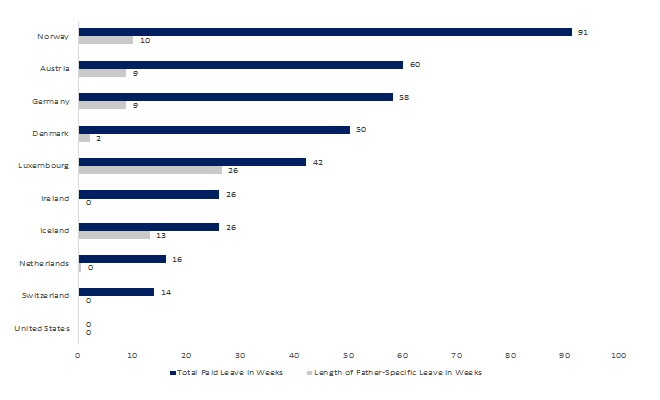

Paid parental leave improves financial security for families, especially for the less well off. It also increases female labour force participation, as more women return to their jobs after birth or adoption, improving the trajectory of their long-term earnings.[32] This in turn improves productivity and growth. The US is the only OECD country that does not have a statutory entitlement of paid leave for new parents.[33] All countries compared here with the exception of the United States and Ireland ensure between 50-100 percent of average earnings during the period of maternity leave.[34] More countries are also offering paternity leave, or parental leave that can be shared equally between parents. Longer leave for fathers is associated with improved economic outcomes for women, and equalises the costs for firms, who may otherwise be more likely to hire men.[35]

Figure 4: Total Weeks of Paid Leave for New Parents

Affordable childcare is essential for improving labour force participation. When costs for childcare are too high compared to potential earnings, people (usually women) remain outside the paid labour market. In the United States, less than one-third of 0-2 year olds are in early childhood education or childcare. That is compared to more than 60 percent in Luxembourg, and more than 50 percent in Iceland, Norway, Netherlands and Denmark.[37] Among 3-5 year olds in the US, 65 percent are enrolled in childcare or early childhood education compared to the OECD average of 85 percent.[38] Costs are one potential explanation. For a single parent with two children earning an average wage in the US, the cost for full-time childcare is nearly one-third (26 percent) of net household income.[39]

Figure 5: Net Childcare Costs for Parents Using Childcare, Percent of Net Household Income

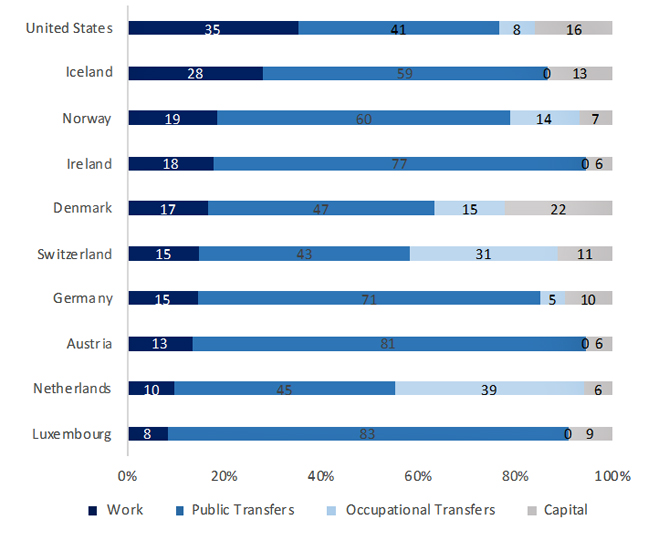

Social security is by far the largest social expenditure in the US at 7.1 percent of GDP.[40] Despite this, the US has a high rate of old-age poverty compared to other rich countries, at 23 percent of those above the age of 65.[41] The retirement savings system in the US leaves huge gaps in coverage and depends heavily on individual savings. The 2008 financial crisis hugely impacted retirement investments and individual savings and assets. Today, for more than one-third of Americans over the age of 65, their main source of income is through work.[42]Occupational transfers account for just eight percent of income for retirees, as many Americans do not have access to retirement plans through their employers. Among private-sector workers in the US in 2018, only 51 percent had access to defined contribution plans, and a mere four percent had access to defined benefit plans.[43] Gender gaps in pensions in the US are also significant, as women tend to have lower earnings and thus make smaller contributions to retirement plans, and in turn accumulate less savings.[44] Among men over 65, the poverty rate is 20 percent, while it is 26 percent for women. Even as the American system depends on individual savings, 40 percent of Americans do not have a retirement savings account.[45]

Figure 6: Income Source of Older People, Percent of Disposable Income

In times of crisis such as the ongoing pandemic, the inadequacies of the American social protection system become all too clear. Many Americans without health insurance have been afraid to get tested or to seek needed treatment; this poses a risk to many other people. Even those with health insurance worry that they will be left with exorbitant medical bills. This insecurity has led many individuals with health insurance to forgo testing and treatment.[46] Half of insured Americans have health insurance provided by their employers. Job loss now could impact insurance coverage for many, which will pose a major threat if the virus abates but comes back in another wave.

For many Americans, especially those without paid sick leave (24 percent of the workforce) the opportunity cost of not working are high. This has forced many, even those who are sick, to go to work anyway, potentially spreading the virus further.[47] Moreover, an estimated 3.4 million people filed for unemployment insurance in the week leading up to 21 March; it is the largest such population in contemporary American history.[48] Current eligibility criteria for unemployment insurance, such as proof that you are looking for work, make access to needed benefits arduous and often leave large gaps in coverage even in normal circumstances.

Conclusion

Instituting social protection measures in a time of crisis is costly, both in terms of resources and time. Yet it is clear that these safety nets are required to protect people and stabilise the economy. In the aftermath of COVID-19, institutionalising effective basic social protections for all Americans will help ensure future resilience and growth.

This will require healthcare reform that either creates a single-payer system or a public option that expands affordable healthcare coverage. In the latter, the basic requirements of private insurance outlined in the ACA or ‘Obama Care’ should be reinstated to reverse the increase in the underinsured population. The employment insurance system in the US was designed in 1935. What are needed are reforms such as those proposed by former President Barack Obama to protect workers with wage insurance, increase coverage for those who fall through the cracks, and make it easier for workers to find jobs.[49]

As has been discussed in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election, mandating paid parental leave for 12 weeks or longer is an important step. The US should follow in the footsteps of other countries by allowing that time to be split by parents. In addition, lawmakers need to improve work-family policies to guarantee affordable, quality childcare options for families, such as the Child Care for Working Families Act 2019.[50]

Finally, proposals by the Democratic presidential candidates that aim to increase social security coverage should be considered. These include counting the time that individuals have spent caring for children, elderly or the sick towards contributions, and increasing benefits for low-income workers financed through tax increases at the very top of the distribution. The current crisis has shed light on major faultlines in the US’ basic social protections. Addressing immediate needs imposed by the health crisis is priority, but longer-term reforms will be critical.

Endnotes

[a] According to the widely used poverty threshold of 60% of the median income.

[b] Individuals that had health insurance all year but forewent medical treatment due to costs.

[1] “Trump Signs Relief Package: China Reports Zero New Local Infections”, The New York Times, March 18, 2020.

[2] Emily Cochrane and Nicholas Fandos, “Congress and White House Strike Deal for $2 Trillion Stimulus Package”, The New York Times, March 25, 2020.

[3] World Health Organization, “COVID-19 Situation Dashboard”, accessed 02 April 2020.

[4] OECD, “Gross domestic product (Indicator)”, (2020). doi: 10.1787/dc2f7aec-en.

[5] Julia Lynch, , “A Cross-National Perspective on the American Welfare State,” Oxford Handbook of U.S. Social Policy, Ed. Daniel Beland l, Kimberly J. Morgan, and Christopher Howard. (2014).

[6] Julia Lynch, , “A Cross-National Perspective on the American Welfare State,” Oxford Handbook of U.S. Social Policy, Ed. Daniel Beland l, Kimberly J. Morgan, and Christopher Howard. (2014).

[7] OECD, “Total Public and Primary Private Health Insurance (Indicator)“ OECD Health Stat: Social Protections, (2017).

[8] “World Social Protection Report 2017–19: Universal social protection to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals” International Labour Office, Geneva (2017).

[9] OECD, “Net childcare costs (indicator),”(2020). doi: 10.1787/e328a9ee-en (Accessed on 25 March 2020)

[10] OECD, “Pensions at a Glance,” (2019).

[11] Jennifer Tolbert, Kendal Orgera, Natalie Singer, and Anthony Damico, “Key Facts About the Uninsured Population,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, (2019).

[12] Tolbert, Orgera, Singer, and Damico, “Key Facts About the Uninsured Population,” (2019).

[13] Tolbert, Orgera, Singer, and Damico, “Key Facts About the Uninsured Population,” (2019): 13.

[14] The Commonwealth Fund, “Underinsured Rate Rose from 2014-2018, With Greatest Growth Among People in Employer Health Plans”, The Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, (2018).

[15] Jennifer Tolbert, Kendal Orgera, Natalie Singer, and Anthony Damico, “Key Facts About the Uninsured Population,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, (2019).[16] The Commonwealth Fund, “Underinsured Rate Rose from 2014-2018, With Greatest Growth Among People in Employer Health Plans”, The Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, (2018).

[17] OECD, “Health Spending (indicator),” OECD (2020).

[18] Health System Tracker, “On a per capita basis, health spending has grown substantially”, Kaiser family Foundation Analysis of National Health Expenditure Data, (2018).

[19] Health System Tracker, “Health Spending Growth has Outpaced Growth of the U.S. Economy”, Kaiser family Foundation Analysis of National Health Expenditure Data, (2018).

[20] Liza Hamel, Mira Norton, Karen Pollitz, Larry Levitt, Gary Claxton and Mollyann Brodie, “The Burden of Medical Debt: Results from the Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times Medical Bills Survey,” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. (2016): 1.

[21] OECD, “Total Public and Primary Private Health Insurance (Indicator)”, OECD Stat. (2018).

[22] “World Social Protection Report 2017–19: Universal social protection to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals” International Labour Office, Geneva (2017): 40.

[23] Robert Moffitt, “Unemployment Benefits and Unemployment: The Challenge of Unemployment Benefits is to Protect Workers While Minimizing Undesirable Side Effects,” IZA World of Labor (2014): 13. doi: 10.15185/izawol.13

[24] “World Social Protection Report 2017–19: Universal social protection to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals” International Labour Office, Geneva (2017): 49.

[25] Robert Moffitt, “Unemployment Benefits and Unemployment: The Challenge of Unemployment Benefits is to Protect Workers While Minimizing Undesirable Side Effects,” IZA World of Labor (2014): 13. doi: 10.15185/izawol.13

[26] “World Social Protection Report 2017–19: Universal social protection to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals” International Labour Office, Geneva (2017).

[27] “World Social Protection Report Data 2017-19”, International Labour Organization (2019).

[28] OECD, “Society at a Glance 2019: Social Indicators,” OECD Publishing, Paris (2019): 102.

[29]“Adequacy of minimum income benefits (indicator)” OECD (2020). doi: 10.1787/dcb819cd-en)

[30] “Adequacy of minimum income benefits (indicator)” OECD (2020). doi: 10.1787/dcb819cd-en

[31] “Adequacy of minimum income benefits (indicator)” OECD (2020). doi: 10.1787/dcb819cd-en

[32] OECD, “OECD Employment Outlook 2018”, OECD Publishing, (2018). Paris.

[33] OECD, “Parental Leave Systems”, OECD Family Database. (2019).

[34] “OECD, “Parental Leave Systems,” OECD Family Database. (2019): 3.

[35] Barbara Gault, Heidi Hartmann, Ariane Hegewisch, Jessica Milli and Lindsey Reichlin, “Paid Parental Leave in the United States”, Institute for Women’s Policy Research, (2014).

[36] OECD, “Gender Data Portal”, (2016).

[37] OECD, “Enrollment in Childcare and Pre-School,” OECD Family Database. (2019): 2.

[38] OECD, “Enrollment in Childcare and Pre-School,” OECD Family Database. (2019): 5.

[39] OECD, “Net childcare costs (indicator),”(2020). doi: 10.1787/e328a9ee-en (Accessed on 25 March 2020)

[40] OECD, “Pension spending (indicator),” (2020). doi: 10.1787/a041f4ef-en (Accessed on 24 March 2020)

[41] “America’s Pensions System is Now Less of A Mess,” The Economist, (2020).

[42] OECD, “Pensions at a Glance,” (2019).

[43] “51 Percent of Private Industry Workers had Access to Only Defined Contribution Retirement Plans,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, (2018).

[44] Monique Morrissey, “The State of American Retirement: How 401(K)s Have Failed Most American Workers,” Economic Policy Institute, (2016).

[45] Monique Morrissey, “The State of American Retirement: How 401(K)s Have Failed Most American Workers,” Economic Policy Institute, (2016).

[46] Matthew Rae, Gary Claxton, Nisha Kurani, Daniel McDermott and Cynthia Cox, “Potential Costs of Coronavirus Treatment for People With Employer Coverage”, Systems Tracker: Health Spending (March 13, 2020).

[47] Drew Desliver, “As Coronavirus Spreads, Which U.S. Workers have Paid Sick Leave – And Which Don’t?” Pew Research Center.

[48] Aaron Sojourner and Paul Goldsmith-Pinkham, “The Coronavirus Crisis Led to a Record-breaking Spike in Weekly Unemployment Insurance Claims”, Economic Policy Institute, (March 24, 2020).

[49] “Fact Sheet: Improving Economic Security by Strengthening and Modernizing the Unemployment Insurance System”, Office of the Press Secretary, The White House. (2016).

[50] “Child Care for Working Families Act 2019”.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Terri Chapman is Programme Manager at ORF America. Her research interests include urban and regional development welfare analysis and inequality.

Read More +