In the recently concluded assembly elections for five states, while much of the attention has been on the BJP’s spectacular victory in politically significant Uttar Pradesh, the real surprise is the Punjab outcome. The Aam Aadmi Party’s historic victory in a state with no reliable voting base and a weak and invisible party organisation is a fairy tale story almost similar to what the newbie party achieved in the Delhi elections in 2015. The AAP’s victory has no parallel from the fact that not only has it decimated the ruling Congress where the incumbent chief minister and party president lost their seats, the bigger shocker was 100-year Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) ended up just winning 3 seats and party’s old warhorse and five-term chief minister Prakash Singh Badal could not retain his seat in Lambi. Even SAD’s president Sukhbir Badal and former Congress Chief Minister Amarinder Singh could not retain their own seats. In short, the 2022 elections have proven to be a Waterloo for the old and established parties in Punjab.

In Punjab, average voters were strongly egging for change or badlav, which is evident in AAP’s strong performance in all regions of the state.

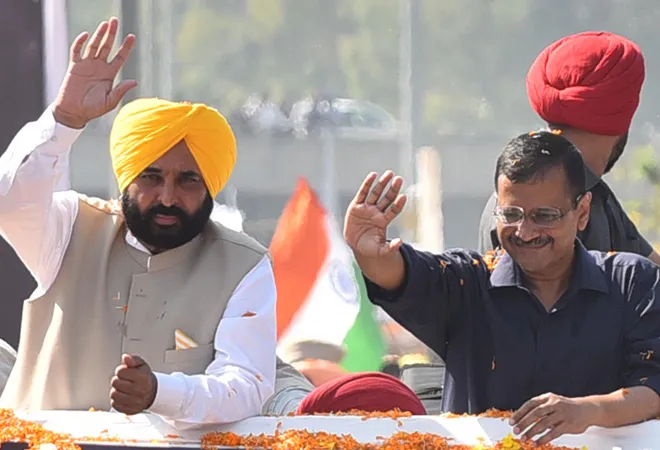

How did an eight-year-old party achieve this magical feat in a state where its party unit was dissolved by AAP chief Arvind Kejriwal over indiscipline after the 2017 electoral debacle? Behind the AAP revolution in Punjab, there is a single and uncomplicated factor that has vastly shaped the insurgent party’s historic victory: the ‘Delhi Model’. Of course, this does not discount the role of other factors. For instance, a key factor was the electorate’s disillusionment with the established parties in the state. This is nowhere more prominent than the ruling Congress party which, despite winning an inspiring election in 2017, allowed itself to be consumed in factionalism and leadership war. Chief Minister Amarinder Singh’s unceremonious removal by the party’s leadership from Delhi, his running feud with newly appointed party president Navjot Singh Sidhu and the party’s known Dalit face Charanjit Singh Channi’s elevation to the hot-seat just months before elections played a key role in the party’s debacle. Such spectacles would have diverted a significant section of its traditional voters (as reflected in the party’s lacklustre performance in Doaba and Maja regions) to AAP. Whereas, Akalis were seen as an old, tired and corrupt cliché by average voters, which is reflected in all old warhorses including Prakash Singh Badal’s loss. In Punjab, average voters were strongly egging for change or badlav, which is evident in AAP’s strong performance in all regions of the state. While the role of local faces such as Bhagwant Mann cannot be ignored, the key anchor was AAP’s Delhi Model and its aspirational appeal in Punjab, which perfectly captured the mood for change in Punjab.

How Delhi model resonated in Punjab

As said earlier, a disillusioned voter in Punjab was desperately looking for a change and a new template of governance that could address deep-rooted corruption, patronage politics and end elite control. The Kejriwal government’s ‘Delhi Model’ of governance based on efficient delivery of public services found a strong resonance among voters in Punjab. The Delhi Model, as has been aggressively promoted by the AAP government, comprises four crucial planks of welfare delivery - quality school education, healthcare, water and electricity at affordable rates.

With slogans such as ‘education first’, the AAP-led government infused a fresh dose of energy into a moribund education system, especially the government-run schools in the capital.

Those who have been following the national capital’s education space know well the huge turnaround in once ailing government schools. After it won the landslide in 2015 in Delhi, the AAP government singled out education as a key area of building its credentials. With slogans such as ‘education first’, the AAP-led government infused a fresh dose of energy into a moribund education system, especially the government-run schools in the capital. The AAP government under the leadership of deputy chief minister Manish Sisodia, who holds the education portfolio, allotted the highest funds to education, introduced new teacher training courses for students, and infused money to improve the ailing schooling infrastructure. A concerted and much focussed effort produced quick positive results. For instance, a Delhi government school, Rajkiya Pratibha Vikas Vidyalaya in Dwarka, was ranked number one among all government-run day schools in India, while two others have made it to the top ten in 2019. Since then, many other schools have joined the rank. The net result is that more and more students from private schools are joining government schools in Delhi.

Beyond school education, there has been a visible transformation in healthcare access and quality. Delhi’s Mohalla Clinics have acquired national and international attention in the last few years. What also helped the broader appeal of the Delhi Model is that additional packages such as electricity subsidies (free up to 200 units), free bus rides for women, drinking water for 24X7 have earned the goodwill of most residents of the national capital. AAP’s back-to-back landslide victory in 2020 despite facing a massive challenge from the BJP is a vindication of the success of the Delhi Model.

The party managed to connect with the women voters by promising them monthly cash grants of Rs 1,000, buttressing the narrative of a dignified life for women in some way within a societal setting marred by traditions of patriarchy.

Thus, for a state like Punjab where narratives of patronage politics, corruption-tainted political elite and high electricity rates, farmers’ growing dissatisfaction over the stalled transition of the ‘green economy’ increasingly saw the merit in the Delhi Model that assures corruption-free and efficient delivery of public services. What did the trick is AAP’s smart mix of welfarism with freebies. The party managed to connect with the women voters by promising them monthly cash grants of Rs 1,000, buttressing the narrative of a dignified life for women in some way within a societal setting marred by traditions of patriarchy. This seems to have worked given AAP’s good track record of delivering its key promises in Delhi and Kejriwal’s own image as an anti-corruption activist.

Tough road ahead

While the victory was a sweet reward for its hard work in Delhi, governing Punjab and delivering on the Delhi Model is not going to be easy. Running a rich city with a stable revenue base and strong governance legacy (largely due to the late Sheila Dixit’s 15-year stint) is probably easier than a full-fledged state with multiple, structural crises afflicting the key northern state. Not only is Punjab today facing a huge debt burden due to successive governments' uncontrolled subsidies and mismanagement of public finances, the state is badly caught up in the transition trap of the green economy. The recent year-long farmers' protest is testimony to the crisis that is affecting most of the small and marginal farmers in this key state. It has to be seen how the AAP can address some of these structural crises and how it can transform education, health and other public services with a depleted coffer.

This commentary originally appeared in India Today.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV