-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Expanding access to innovative drugs is central to addressing current and future global health challenges. This is particularly critical for low- and middle-income economies as they look to reduce disease burdens and strengthen healthcare delivery in fiscally sustainable ways. Against the backdrop of a heightened global debate on drug access, patents and prices, what policy frameworks could incentivise life sciences companies to continue making risky investments into the research of transformative cures, sustain shareholder value — and make these cures available to patients who can least afford but most need them?

On October 17, ORF convened a discussion to explore policy options to help facilitate both access and innovation in healthcare. Speakers included Tanoubi Ngangom, Head of Programmes, ORF; Dr. Usha Rao, Assistant Controller General for Patents, Indian Patent Office; Aaron Brinkworth, Executive Director, Global Patient Solutions, Gilead Sciences; and Patrick Kilbride, Senior Vice President, Global Innovation Policy Center, U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The discussion was moderated by Ashok Malik, Distinguished Fellow, ORF.

Building on our 2016 research paper, “Voluntary Licensing: Access to Markets for Access to Health,” the discussion explored the role of voluntary licensing in the real world—the complexities, alternatives and best practices—based on new industry data. Here are the top five takeaways from the discussion:

With a VL, patent holders use their own discretion to offer third parties (generally, generics manufacturers) a license to produce, market and distribute a patented drug. Unlike compulsory licences (CLs), the non-confrontational nature of VLs allows access while accounting for the interests of all parties: patients, public health interest groups, generic drugs manufacturers and originator pharmaceutical companies.

VLs emerged as an industry response to the political and ethical pressure on many governments in emerging markets to issue CLs and government use licenses, and have since matured as a policy instrument that offers a win-win for all stakeholders. VLs also provide a balance between the protection of public health and intellectual property (IP) rights by strongly aligning incentives of governments and originator manufacturers. Industry experience shows that IP protection promotes cooperation among innovators, governments, the healthcare community and civil society that may allow comprehensive approaches to effectively address significant unmet public health needs.

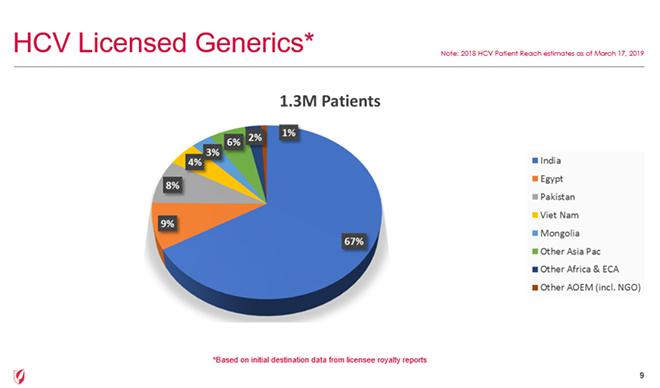

Earlier this year, a study by Bryony Simmons, Graham Cook and Marisa Miraldo in The Lancet showed that VL initiatives introduced in 2014 appeared to substantially improve hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment uptake in eligible countries by 2016. Further validating the study’s findings, Gilead Sciences reported new data at the ORF event on HCV treatment uptake under their VL program. By the end of 2018, Gilead’s VLs allowed 1.3 million patients in low- and middle-income countries to access HCV treatment.

Specifically, small countries like Vietnam successfully enabled access to treatment for over 50,000 patients over four years, averaging over 15,000 patients per year in 2018. See data for other countries in the chart below.

This contrasts with another country in the region, which instead used a CL to make HCV drug sofosbuvir available over the same period, and reportedly treated only 1,500 patients over a year.

Gilead’s VL experience also demonstrated that competition between licensed generic manufacturers have significantly driven down prices. In addition, patent holders also offer discounted royalty rates if licensees meet global standards of quality, safety and efficacy per the WHO Prequalification. Reduced royalties can translate into lower prices for patients. Conversely, CLs, although very sparingly used in countries like India, generally give one or two companies market dominance, which gives little need for manufacturers to drop their prices.

A VL is self-initiated and cannot be given to any country that simply asks for it. There is a meaningful difference between countries’ willingness to pay and their ability to pay. The therapeutic area, burden of disease and unmet need also have considerable bearing on the importance of collaboration. Often, there are also strategic concerns that play out like the need to pre-empt licensees from selling or exporting to non-licensed territories. Collaboration often fosters investments in well-trained health workforces, screening and linkage to care and empowered patient communities.

On the other hand, CLs—or other maximalist, involuntary policies—exacerbate principal-agent problems, discourage engagement and collaboration between industry and government, and fail to achieve maximum results for patients.

Patents—if used responsibly—can be engines that expand access to medicines and also inspire local innovation. Since the launch of India’s National IP Policy in 2016, increased awareness of patent protection has led to respect for IP, translating into an environment that is conductive to discovery and innovation.

IP and access are two sides of the same coin: While patent protection incentivises the research of unmet medical needs, collaborative access polices bring cutting-edge innovation closer to the patients in need. However, patent grants should be based on the technical and scientific value of the patent and not on access policy considerations. Instead, the market economy should guide decisions on different access policies. Patent holders should be free to propose access strategies in ways that they see a reasonable return on the value of their investment.

Voluntarily licensed generics are not a silver bullet for access. Real-world experience shows that when generic products enter the market, increased access does not automatically follow. In reality, expanding access to medicines requires cross-cutting investments in health systems, screening and education—all products of collaboration.

Fortunately, the advent of Artificial Intelligence and other such mechanisms usher an opportunity to bring down prices of research and drug discovery. That said, the commercialisation process—the journey of research from the lab to the market—is still time consuming and expensive. The market of life saving drugs is a market like no other, that needs approaches that transcend the gap that often separates economics and ethics. VLs represent one such very effective multi-stakeholder approach.

While this discussion explored the complexities of VLs to increase access to life-saving medicines, speakers acknowledged that there is immense need for additional research into practical applications of other collaborative policies that encourage innovation and access.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.