Introduction

“The failure of a loan usually represents miscalculations on both sides of the transaction or distortions in the lending process itself.”

—Radelet, Sachs, Cooper and Bosworth (1998)

This quote captures one of the fundamental reasons for India’s non-performing assets (NPA) problem as more debts provided by the banks, particularly by the state-owned public sector banks (PSBs), turn into risky category credits. The accumulation of bad loans happened over an extended period of time, and today it threatens to hamper the revival of economic growth by choking the credit supply channel of the economy.

Increasing cases of wilful defaults and frauds have recently been in the news. These cases are often perceived as the primary reason behind the accumulation of bad loans in the Indian banking system. However, the principal factor is the over-expectation of economic growth, which makes the banking system disburse credit competitively during the boom of the business cycle. If the high expectation of growth does not materialise, bad loans accumulate as borrowers are unable to repay due to stalling or closure of the big development projects.

When an economy experiences healthy GDP growth, a substantial part of it is financed by the credit supplied by the banking system. As long as the GDP keeps growing, the repayment schedule does not get substantially affected. However, whenever the GDP growth slows down, the bad loans tend to increase due to a host of macroeconomic factors, primary among them: interest rate, inflation, unemployment rate, and change in the exchange rates.[1]

Bank-related micro indicators such as capital adequacy, size of the bank, the history of NPA and return on financial assets also contribute to the accumulation of bad loans. Credit policy or the practice of extending credit by banks and “herd behaviour” of the banks also play a role in growth of NPAs in India.[2]

Accumulated NPAs in the Indian banking system, specifically in the PSBs, have adverse effects on credit disbursement. Increasing amounts of bad loans have prompted the banks to be extra cautious. This in turn has caused the drying up of the credit channel to the economy in general and to the industry in particular, making economic revival more difficult.

Two components are key in resolving the NPA problem: the immediate task of resolving the current accumulation in the PSBs, and the more important long-term task of ensuring that NPAs do not accumulate again to this proportion. Recapitalisation in various forms and other kinds of finance mobilisation by the government and the PSBs over a long period of time can clean up the balance sheets. Given the significant volume of the NPAs, this may take time, but sustained effort to eradicate these risky category credits can make the banks’ balance sheets healthy again. It can be done, albeit involving a strenuous and time-consuming process.

Tackling the second task, however—the prevention of further future accumulation whenever the GDP grows at healthy rates again—is trickier. The model of financing big-ticket projects through deposit-taking commercial banks must be scrutinised and alternative modes of financing must be explored. It will help to create a new-age development finance institution (DFI) model for big development projects, utilising new financial avenues such as the sovereign wealth funds and different versions of capital, bond and equity funds. A project finance approach for these projects, along with new DFIs, may provide a long-term answer to the big-ticket credit question.

MOUNTING NON-PERFORMING ASSETS IN INDIA

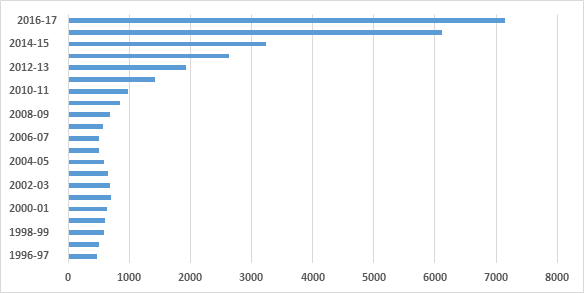

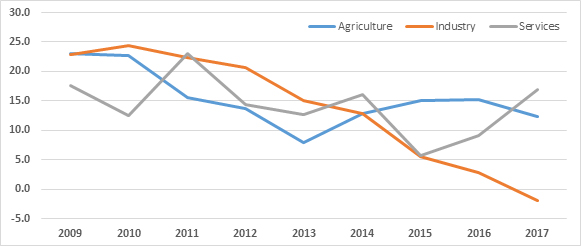

| Figure 1: Gross Non-Performing Assets of Commercial Banks in India (In INR Billion) |

|

| Source: Reserve Bank of India (dbie.rbi.org.in). |

During the mid-1990s, due to the resolution of bad loans then—primarily in priority and non-priority agriculture sector and small industries—the quantum of gross NPAs (GNPAs) in India was at manageable levels in absolute amounts. In 1996–97, the amount of GNPAs of scheduled commercial banks were at INR 473.0 billion. The volume of these bad loans started increasing rapidly after 2007–08 and reached around INR 6,119.5 billion by the end of 2015–16, which is approximately a 13-times increase in the absolute volume over approximately 20 years. As a percentage of gross advances, the amount of GNPAs was 15.7 percent in 1996–97, going down to 2.3 percent in 2008–09, only to rise once again to 7.5 percent in 2015–16. In 2016–17 GNPA further grew to an accumulated value of INR 7,148.98 billion.

This implies that the extension of credit or advances has increased manifold in this time period, approximately 27 times in gross advances between 1996–97 and 2015-16. Meanwhile, the current GDP at market prices in India has also increased more than nine times. This coincides with one of the basic observations in the existing academic literature that a rise in GDP induces an expansion in credit, which subsequently gives rise to NPAs, particularly if regulations are not adequate.

During the period 2004–08, India experienced a rapid pace of GDP growth, with the average GDP growth rate at constant prices reaching an unprecedented high of 8.8 percent per annum. This period was marked by a conscious effort to close the widening infrastructure gap as lack of infrastructure is perceived to be one of the major bottlenecks preventing the manufacturing sector from increasing its share in GDP. In this effort, crucial infrastructure investments were undertaken either by the private sector or by public–private partnership models.

Private players in these infrastructure projects typically relied on funds borrowed from the PSBs, under active policy facilitation by the central government. However, after 2011, as the Indian economy finally started to slow down, many of these infrastructure projects were stalled. Consequently, bad loans started accumulating in PSB balance sheets. As seen in Figure 1, GNPAs shot up in the system abruptly after 2011.

The recent jump in NPAs, particularly after 2012–13, can also be attributed in part to the transparency pressures imposed by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) on the scheduled commercial banks as the regulator of the Indian banking system. Indian commercial banks tend to underreport the amount of NPAs and employ other methods—restructuring or rolling over existing loans—to make their balance sheets look cleaner and healthier than they are. Admission of NPAs compels the banks to make capital provisioning for those bad loans, which will in turn reduce their profit margins in the books. Therefore, official NPA figures on the banks’ balance sheets may not always represent the actual extent of the problem.

EFFECT OF GDP GROWTH ON NPA GROWTH

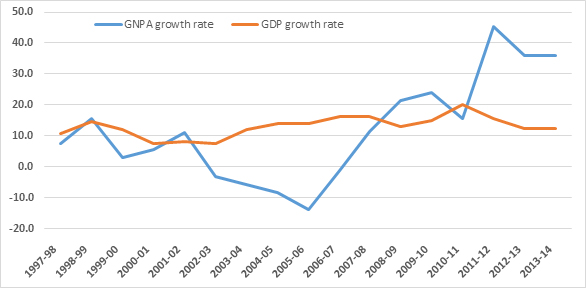

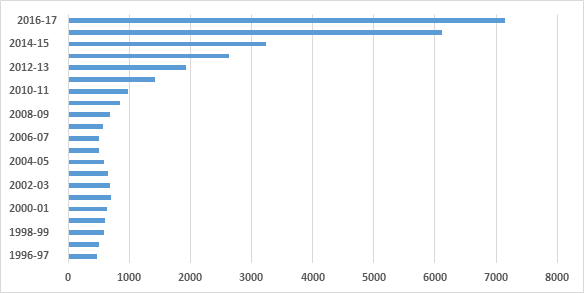

Figure 2: Trends in Growth Rates of Gross Non-Performing Assets And GDP

(At Current Market Prices) |

|

|

* All figures are in percentage.

* New series, with base year 2011–12, starts only at 2011–12 and does not provide any other past year’s data. So, to have a longer series, GDP growth rates are calculated with the older series with base year 2004–05, and GNPA growth rates of corresponding years are considered to make the comparison.

|

| Source: Reserve Bank of India (dbie.rbi.org.in). |

The trends in the growth rates of GNPAs and GDP (at current market prices) during 1997–98 to 2013–14, show that bad loans tend to grow with a lag in the GDP growth rates. This implies that once the GDP growth rate rises, the Indian banking system is likely to extend more credit, and roughly after two to three years of good growth, bad loans start showing up on the banks’ balance sheets, as seen in Figure 2. This is consistent with global trends.

In terms of GDP growth, the Indian economy had a good run during 2004–08, before the financial crisis hit the US and affected economic growth in most regions. Growth rates of GNPAs started gaining momentum after 2005–06, two years after GDP started rising during this period.

The lag has recently narrowed down to one year or so. After 2010–11, the trend suggests that a directly proportional relationship between GNPA and GDP growth rates has emerged with less amount of lag time. The corresponding growth rates of GNPA and GDP in 2012–13 and 2013–14 have mostly moved in tandem.

Possibly, the huge jump in the quantum of NPAs in recent times made the bad loans more sensitive to the growth in GDP, and this has reduced the time lag between the growth rates in NPA and GDP. In other words, the accumulated amount of bad loans made the banks apprehensive about extending loans liberally. Thus, any small fall in the GDP growth rate elicits a lot of caution, leading to decreased disbursal of bank credit, which in turn slows down the GNPA growth rate. When the GDP rate slows down, therefore, it seems that GNPA and GDP growth rates are moving in tandem with less time lag.

NPA GROWTH AND LENDING RATES

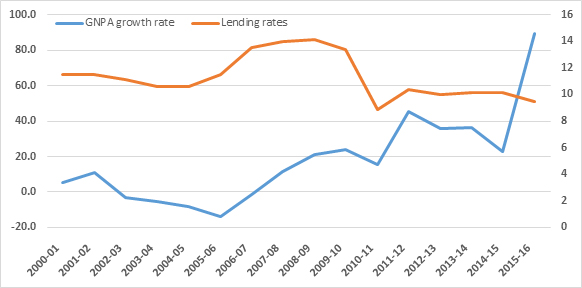

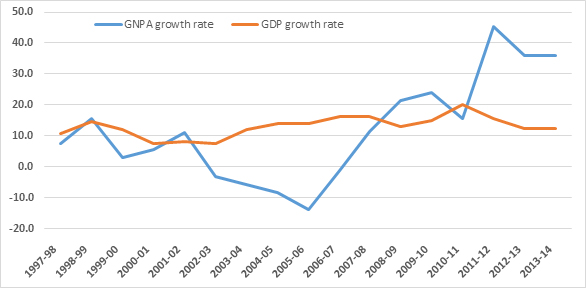

| Figure 3: Trends in Growth Rates of GNPA and Lending Rates |

|

|

* All figures are in percentage.

* Data on minimum general key lending rates prescribed by RBI refers to the prime lending rates of five major public-sector banks. Median point of the entire range of lending rates are taken for the respective years.

|

| Source: Reserve Bank of India (dbie.rbi.org.in). |

As found in the literature, lending rates usually have a strong effect on bad loans. As lending rates increase, NPAs tend to increase due to further pressure on repayment commitments and vice versa.

The trends suggest that this relationship holds true in India as well. Interestingly, by the end of 2015–16, the GNPA growth rate increased substantially despite the lending rates having decreased in the same year. This demonstrates, once again, the accumulated effect of bad loans, i.e. even if there is a decrease in the lending rates, bad loans may keep on accumulating due to their sheer volume. This discourages banks from extending credit to any sector of the economy due to the already accumulated significant amount of bad loans in their balance sheets. Figure 5 shows that there is a lack of demand for industrial credit as well.

Thus, there is a need for an urgent resolution of the bad loans currently plaguing the Indian banking system. Further accumulation and postponing resolution may aggravate the problem.

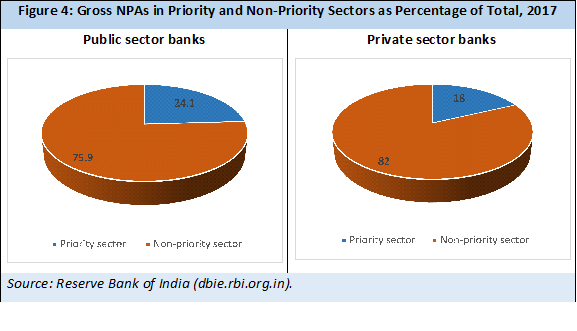

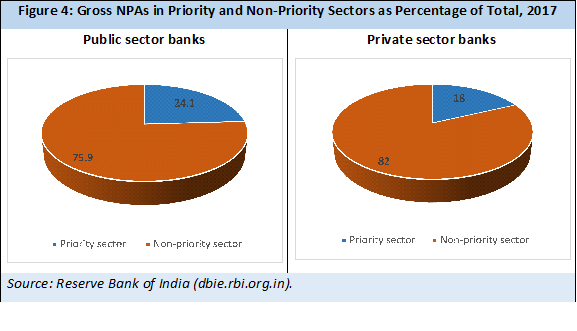

COMPOSITION OF NPAs IN PRIORITY AND NON-PRIORITY SECTORS

In India, priority sector lending is often cited as a significant reason for the accumulation of NPAs. The banks, under priority sector lending, extend credit to agriculture and SMEs. However, the reality is that for both PSU banks and private sector banks, accumulated NPAs in the priority sector is relatively small compared to the accumulated NPAs in the non-priority sector (see Figure 4).

Total non-food credit outstanding as of 31 March 2017 was INR 70,946.89 billion, of which priority sector lending was at INR 24,356.53 billion, including an INR 9,909.22-billion credit to agriculture and allied activities and INR 9019.75-billion credit to micro and small enterprises. In non-priority sectors, INR 26,800.25 billion was extended to the industry; INR 18,022.43 billion was extended to services sector; and INR 16,200.34 billion worth of credit was extended for various kinds of personal loans.[3] The composition of extended credit and NPAs across both priority and non-priority sectors shows that the problem of bad loans in Indian scheduled commercial banks are not primarily related to the priority sector; rather, the root cause lies in non-priority sector lending.

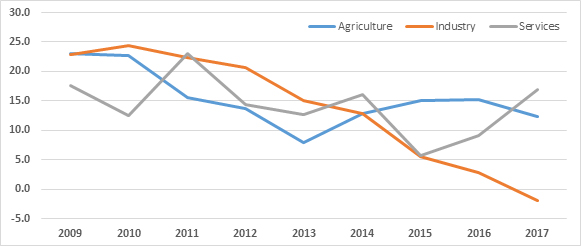

SLOWDOWN IN INDUSTRIAL CREDIT GROWTH DUE TO ACCUMULATION OF NPAs

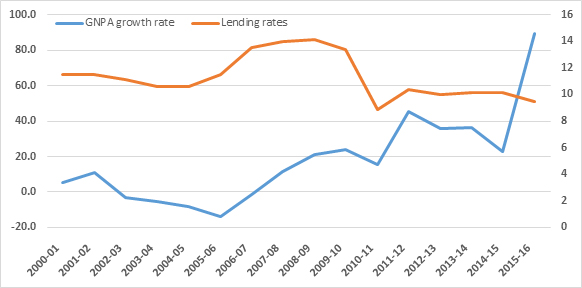

| Figure 5: Sectoral Bank Credit Growth Rates (In Percentage) |

Source: Reserve Bank of India (dbie.rbi.org.in).

The biggest fallout of NPA accumulation, particularly in the PSBs, is that industrial credit growth rate has plunged in the last few years: it was at 24.4 percent in 2010 and has kept decreasing since then. In 2017, it plummeted to the negative zone. Compared to 2016, industrial credit growth rate decreased by 1.9 percent in 2017.

Within three basic sectors of the economy, industry is the worst performer in credit growth. While credit growth in the services sector was revived after 2015, agricultural credit growth has remained above 10 percent since 2014. However, the absolute value of industrial credit still remains the biggest. Outstanding figures of bank credit to industry, as of March 2017, stood at INR 26,798.33 billion, to services at INR 18,022.37 billion, and outstanding credit to agriculture was at INR 9,923.86 billion.

Reviving industrial credit is crucial for the health of the overall economy, simply because industry—particularly manufacturing—tends to create more employment than the other two sectors. Economic forward and backward linkages are more pronounced in a typical industry, compared to services or agriculture.

No economic revival is possible unless GDP growth is accompanied by a sizeable increase in employment, for which manufacturing plays a pivotal role. Jobless growth will not be able to create adequate purchasing power in the hands of the ordinary consumer, and without more purchasing power—and consequently, more consumption expenditure—no economic development can sustain in the long run.

TIME FOR A REVIVAL OF DEVELOPMENT FINANCE INSTITUTIONS?

The accumulation of NPAs in the PSBs and private sector banks, and the subsequent slowdown in industrial credit growth, not only hamper the revival of the economy but also put several small depositors of the banks, particularly in the PSBs, at risk. Mounting bad loans suggest a vulnerability in the system, wherein deposit-taking banks have to extend credit for long-term big development projects. The model of providing finance to big development projects through deposit-taking commercial banks’ lending process is visibly failing, and this is one truth very few are willing to admit or discuss.

The situation calls for an alternative model of financing big-ticket investment projects. A re-look at the erstwhile development finance institutions (DFIs) model as the provider of loans in long-term investment projects may provide one such avenue. While replicating government-funded DFIs in today’s liberalised India is practically impossible, the time may have arrived for a new-age DFI model, in which private funds, capital and equity can play a larger role. Such a revamped DFI will take the responsibility of funding big investment away from commercial banks, freeing them from the recurring bad loan accumulation. This can usher in a better, more structured system of risk assessment and finance management for these big long-gestation development projects.

Risk in development financing comes from the long gestation period of the projects. A long tenure of such a loan induces uncertainty in the performance of loan assets. Repayment in long-term project loans crucially depends upon the performance of the project and the cash flows coming out of it, not on collaterals. Collaterals for these projects, if provided, are most often inadequate to cover the much larger project costs and repayment of loans.

The projects can get stalled for many reasons: technological obsolescence, market competition, change in government policies, natural calamities, poor management, or even a drastic fall in demand. These factors have played out in many of the recent infrastructure projects.

Due to these reasons, prior to liberalisation and in the beginning of the planning era, the understanding among policymakers was that banks could only provide limited long-term financing to heavy industries and the housing sector. Banks, which take deposits from all kinds of consumers, have an obligation to provide short-term liquidity to a sizeable number of their customers who have short savings horizons and would prefer to abjure income and capital risks for the safety of their deposits. Providing long-term project financing comes in conflict with such objective of the small depositors, due to mismatch in maturity and liquidity.

Therefore, it was decided that the shortfall in long-term investment in development finance would be met mainly by creating specialised financial institutions with access to more long-term capital directly from the government or the central bank. These DFIs were necessary for two major reasons: (a) inadequate accumulation of capital in the hands of indigenous industrialists; and (b) the absence of markets for long-term finance, e.g. markets for long-term bond or equity.

Funds for the DFIs came from multiple sources: government budgetary allocations, the surpluses of the RBI, and bonds subscribed by other financial institutions, in addition to open markets. Given the reliance on government sources and the implicit sovereign guarantee that the bonds issued by these DFIs carried, the cost of capital was relatively low, facilitating lower-cost lending for long-term purposes. This experiment worked well until liberalisation. Till the 1990s, India successfully used development banking as an effective instrument of late industrialisation.

However, as sweeping financial reform took place in the 1990s, policymakers began seeing DFIs as “distortions in the playing field for commercial banks.” As per the recommendations of the Narasimham Committee, some of these DFIs were allowed to fade into oblivion on their own, while others like the IDBI and the ICICI were allowed to create commercial banks, with which the development banking arms were ‘reverse merged’. Consequently, the investors in capital-intensive projects had to turn to the only remaining source of financing for long-term funding: commercial banks.

In the process, the Indian development finance model ended with banks being encouraged to foray into long-term lending to these development projects. In the distribution of financial assets among banks and all financial institutions (e.g. the cooperative banks, the DFIs, the nationalised insurance companies and various other public institutions), the share of the banks—which had declined from 71 percent to 61 percent between 1981 and 2000—rose to 82 percent by 2012.[4]

These changes created a transformation in the structure of financing of productive activities, especially industry. The importance of financial assistance from the erstwhile development finance sector diminished considerably after 2000, as some of the DFIs had become banks and the rest had been rendered irrelevant.

At the same time, the capital market was expected to emerge as a substitute of these institutions, but new capital issues market for these long-term development projects never flourished as an alternative, except for brief periods of speculative boom in the early 1990s. Thus, in the new millennium, the commercial banks and the private placement market remained the two main sources of external finance for industry. The latter has been specifically targeted by the foreign investors looking for high and/or quick returns. In short, banks continued to be the primary source of long-term big-ticket investment projects in India, from roads and ports to power and steel.[5]

NEW-AGE DFIs AND ALTERNATIVE BIG-TICKET PROJECT FINANCING

In light of the growing NPA problem in India’s banking system, it is time to think about a new version of the DFI model. Such a version can (a) shift the burden away from commercial banks and (b) utilise today’s developed capital and stock markets much more effectively than in the past when these financial segments were virtually absent.

However, it is prudent to clarify that these new-age DFIs cannot be financed by the government as was done in the past. That will be self-defeating, since once again, the burden of debt resolution (in the event the project fails) will fall on the government and on public money. That will be no different from recapitalising the PSBs to clean up the NPAs. Thus, any form of public investment and involvement of public-sector banks in financing big development projects should be ruled out.

However, new avenues of finance—such as sovereign wealth funds, private equity funds and entrepreneur’s risk capital—can be utilised to fund new DFIs. Capital market can also be tapped to source funds. Project-specific bonds can be floated in capital markets. Promoter equity topped with participation of large venture funds can be another avenue.

Project finance can hugely complement the functioning of the new-age DFIs. In project finance, the sponsor company that invests in equity usually forms a special purpose vehicle (SPV), which takes care of the funds procurement and management of a specific large-scale and long-gestation project. The investors invest in these SPVs keeping in mind the long duration of the projects. This mode of financing is useful because it does not ruin the parent company’s balance sheet if the project fails. Moreover, the usual debt-to-total capitalisation ratio is between 50 percent and 90 percent. This high amount of debt component sounds risky,[6] but usually, the consortium of lenders ensures a proper risk management of such SPVs. As a result, the use of high leverage can also be a source of discipline for the SPVs under project finance.

While new-age DFIs can finance project-specific SPVs, bigger wealth and capital funds may be reluctant in financing the DFIs or the project-specific SPVs. However, if the investments in large development projects can be made attractive to the investors by providing positive policy incentives, then these alternative avenues of finance can flourish. The government can help formulate these policy incentives, which will encourage wealth, equity and capital funds to invest some proportion of their funds because big-ticket projects, if successful, usually ensure a steady flow of income for the investors in terms of interest repayments.

Therefore, creating wider debate within the financial sector and other stakeholders of the economy about an improved version of the Indian DFI model can be a good starting point towards the goal to stop NPAs from accumulating in the commercial banking system. The objectives should be to take the burden of financing big development projects away from small deposit-taking commercial banks and to create a financing system in which public money does not play any role.

POSSIBLE PERMANENT RESOLUTION TO NPA ACCUMULATION

The RBI has attempted various instruments to tackle the existing problem of NPA in the banking system: sale to asset-reconstruction companies, strategic debt restructuring, and refinancing or sustainable structuring of stressed assets. These, however, have not produced any encouraging results.

Some experts have suggested creating a single ‘bad loan’ bank, under which all bad loans will be consolidated, so that they can be resolved with simpler and faster decision-making while keeping in mind sectoral complexities and multiplicity of lenders. However, creating a bad bank remains a politically volatile idea and is difficult to implement.

In light of the unsuccessful attempts to restructure/refinance, it is now clear that at a certain point of time, recapitalisation of the affected banks will be the only way to resolve the first part of the problem, i.e. the current level of accumulation. However, given the quantum of NPA in the system, this cannot be in one move. This leaves a mixture of distinct options, all of which can contribute in this recapitalisation process over a longer period of time. The options include budgetary allocation for recapitalisation, channelling part of the RBI dividends transferred to central government annually, better implementation of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, and earnings/profit cuts taken by the bigger banks in the profit-making quarters to write off bad loans.

All of these can contribute gradually to NPA resolution. However, instead of sticking to a single model, an innovative and flexible approach is needed for each affected bank, to be applied on a case-by-case basis. Only then will there be a possibility that this financial mess can be cleared.

References

- Barseghyan, L. “Non-performing loans, prospective bailouts, and Japan’s slowdown.” Journal of Monetary Economics 57, no. 7 (2010): 873–890.

- Bruhn, M. Firms’ use of long-term finance: Why, how and what to do about it? World Bank, 2015. http://blogs.worldbank.org/allaboutfinance/firms-use-long-term-finance-why-how-and-what-do-about-it.

- Chandrasekhar, C.P. Development finance in India. 2014. https://in.boell.org/sites/default/files/uploads/2014/03/development_finance_in_india.pdf

- Chandrasekhar, C.P. and J. Ghosh. “The banking conundrum: Non-performing assets and neo-liberal reform.” Economic and Political Weekly LIII, no. 13 (2018): 129–137.

- Chavan, P. and L. Gambacorta. “Bank lending and loan quality: The case of India.” RBI Working Paper 09 (2016).

- Credit Suisse. India Corporate Health Tracker. 16 February 2017.

- FuriÓ, E. Project finance, the financing alternative for large projects. BBVA, 2016. https://www.bbva.com/en/project-finance-financing-alternative-large-projects/.

- Ghosh, A. “Banking-industry specific and regional economic determinants of non-performing loans: Evidence from US states.” Journal of Financial Stability, no. 20 (2015): 93–104.

- Ghosh, J. Public banks and the burden of private infrastructure investment. 2014. http://www.macroscan.org/cur/feb14/pdf/Public_Banks.pdf.

- Jimenez, G. and J. Saurina. “Credit cycles, credit risk and prudential regulations.” International Journal of Central Banking (June 2006): 65–98.

- Mohan, R. “Transforming Indian banking: In search of a better tomorrow.” Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, Speech Article, January 2003.

- Mohan, R. “Finance for industrial growth.” Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, Speech Article, March 2004.

- Radelet, S.; J.D. Sachs; R.N. Cooper and B.P. Bosworth. “East Asian financial crisis: Diagnosis, remedies, prospects.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, no.1 (1998): 1–90.

- Ranjan, R. and S.C Dhal. “Non-performing loans and terms of credit of public sector banks in India: An empirical assessment.” Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers, 24, no. 3 (2003): 81–121.

- Reddy, Y.V. “Credit policy, systems, and culture.” Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, March 2003 Issue.

- World Bank. India development update: India’s growth story. March 2018, World Bank, New Delhi.

Endnotes

[1] Chavan and Gambacorta (2016), Reddy (2004), Ranjan and Dhal (2003).

[2] Mohan (2003), Mohan (2004), Chandrasekhar (2014), Ghosh (2014).

[3] Other priority-sector loans include priority housing loans, education loans, micro and export credits, and credits for weaker sections. All the data are from the RBI website.

[4] Figures are from Database of the Indian Economy, RBI.

[5] Chandrasekhar and Ghosh (2018), apart from identifying this reason, also cited the fiscal conservatism (“prudence”) under FRBM Act as the other reason. The government directly not spending money on longer-term development projects leaves no financing avenues available other than the banks.

[6] At one level, project finance is indeed risky, mainly because the entire loan is only backed by the project’s expected cash flow and its assets. If the project fails, the assets may not be adequate to cover the entire loan amount.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV