Introduction

On 1 February, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented the interim budget for FY2024-‘25.[1] Of the total allocations of INR47,65,768 crore (approx. US$574 billion[a]), she earmarked INR6,21,541 crore (US$74.8 billion) to the Ministry of Defence (MoD). Representing an increase of 4.7 percent over the previous allocations,[2] the MoD’s interim budget—which amounts to 13 percent of the Central Government Expenditure (CGE)—constitutes the highest allocation among all the ministries. To be sure, the interim allocations of the MoD, like those made by the finance minister for other ministries and departments, may still undergo a change in the full budget of the ensuing financial year—scheduled to be presented in July 2024 after the general elections. Nonetheless, it provides an overview of the general direction of the spending priorities for the defence establishment.

This brief examines the MoD’s latest allocations. It outlines an overview of the MoD’s overall expenditures over the last several years; and examines the drivers of growth in the latest allocations and the impact on military modernisation and Atmanirbharata (self-reliance) in defence. It also discusses the nuances of gross domestic product (GDP)-to-defence ratio in view of current debates on appropriate national defence spendings.

The Geopolitical Environment and India’s Defence Economy

The interim budget comes in the midst of a fast-deteriorating global security environment, marked by wars in Europe and the Middle East, and geopolitical competition among the global powers. The trade and technology war between the United States (US) and China, which began during the Trump administration, has intensified under the Presidency of Joe Biden, causing what many describe as emerging patterns of deglobalisation, friendshoring, and onshoring, and leading to global supply chain disruptions. The economic rivalry between the two powers has taken a turn for the worse as both display their military might in the South China Sea—a gateway for Indian and global trade and commerce. China’s military assertiveness in the Taiwan Strait before and after the 13 January Taiwanese presidential elections, and the US’s determination to thwart any Chinse military misadventure has fueled fears of a war that can easily pull in many countries in the region and beyond.

In India’s neighbourhood, the ongoing border crisis with China is a stark reminder of the challenges that India’s northern neighbour poses to the country’s security. With over 50,000 Indian troops deployed to counter China’s belligerent actions at the border, India’s China posture will likely remain security-driven for the foreseeable future. The China threat, which has historically been land-centric, is increasingly transcending to the maritime, cyber, and space domains. China’s massive naval expansion, in particular, supported by its sprawling shipbuilding industry and buoyed by a massive expansion in military spending, has enabled the Chinese navy to emerge as the biggest in the world.[3]

Though the current focus of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) remains on what it calls the “reunification” of Taiwan, its increasing forays into the Indian Ocean—considered by many as India’s backyard—has put the Indian navy in a difficult situation. Considering that the navy is the smallest service among the Indian armed forces and has the least share in the defence budget, it would remain hard-pressed to match China’s naval capability. It has to perforce seek and strengthen partnerships with like-minded navies to contain Chinese influence, particularly west of Malacca Strait. India’s enthusiastic adoption of the Quad, its tacit support to the AUKUS trilateral strategic military-technology alliance, and New Delhi’s enhanced naval cooperation with navies of friendly countries (including the US, the UK, France, Vietnam, and the Philippines) will remain a defence and security priority for India.

Meanwhile, China’s all-weather friend, Pakistan, continues to pose a threat, though its virulence has diminished in recent times as Pakistan finds itself confronting a severe economic and security crisis. India, however, has to remain vigilant of Pakistan’s deepening strategic and military relations with China. Their growing naval ties, as evident from Pakistan’s imminent induction of several Chinese ships and submarines and their joint naval exercises in the Indian Ocean, is of particular concern for India.[4]

Beyond India’s immediate neighbourhood, the ongoing Israel-Hamas war has rekindled the volatility of the region which is vital for India’s energy security and is home to a large Indian diaspora who send home large amounts of remittances every year. The attack by the Iran-backed Houthis since November last year on shipping in the Red Sea—which handles about 30 percent of global container trade and about US$200 billion worth of annual Indian trade[5]—has caused immense disruption to world trade flows. The military response by the US and UK on Houthi targets in Yemen, Syria and Iraq is threatening a breakout of an all-out regional war. The Indian Navy has responded to the evolving threats in the Red Sea and the adjacent piracy-infested waters by deploying a dozen warships and other platforms to protect its maritime interests.[6] The longer the crisis continues, the greater will be the adverse impact on India’s trade and energy security, besides frittering away the precious naval resources from building core capability to counter the Chinese navy in the Indian Ocean.

The prolonged Russia-Ukraine war carries implications for India’s economic and military security. The war has caused a steep spike in global fuel, food and fertiliser prices, in turn resulting in economic consequences for India. On the security front, Russia’s preoccupation with the war has hindered its ability to supply military equipment and spares to the Indian military, adversely affecting India’s defence modernisation. Moreover, the preoccupation of the defence industry of the West, particularly the US, in providing war supplies to Ukraine (and also Israel) has restricted its ability to supply equipment to India in a timeframe that suits the country’s armed forces.

If the Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Hamas wars are a reminder of the importance of self-reliance in a country’s defence preparedness, it has also brought home a vital lesson for military planners. The protracted wars in both the theaters have moved the concept of short-and-swift war, seen in the first Gulf War in 1990, to the back burner. The war of attrition has exposed the limitations of some of the world’s largest defence industries in producing in large numbers essential war items like munitions. The Indian defence industry, particularly the Ordnance Factories which have undergone structural change in recent years, is now more commercially oriented. For economic reasons, they have less incentive to maintain the “surge” capacity which was earlier the norm. Amid the evolving nature of war, the government has to now plan for spare capacity to manufacture essential war items in large numbers and in the shortest possible timeframe, to meet any exigencies, should the county be forced into a protracted military conflict.

India has so far navigated the global geopolitical challenges through a combination of deft diplomacy and strong security measures. Much of this has been made possible because of the sustained rise of the country’s economic power. The Indian economy, which contracted in 2020-21 due the COVID-19 lockdown, has not only bounced back but continues its growth journey. In just 10 years, India has moved from being the 10th largest economy in the world to become 5th, with an estimated GDP of US$3.7 trillion in 2023-24. For three consecutive years following the 2020-21 contraction, it has registered seven percent-plus growth rates and is poised to become the third largest economy with a GDP of US$5 trillion in the next three years, and a US$7-trillion economy by 2030.[7]

The rise of the Indian economy has also coincided with macroeconomic stability as seen in robust foreign exchange reserves, impressive foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, low current account deficit, and moderate inflation. However, the quality of public expenditure remains a concern in recent years, as the government has resorted to large-scale debt financing to pump-prime economic activity through massive investments in infrastructure.

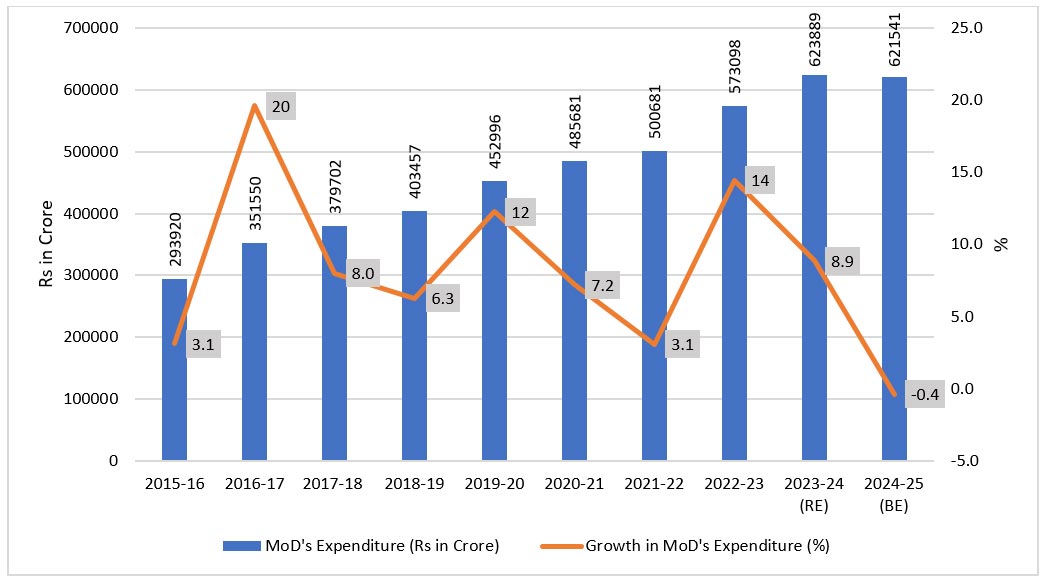

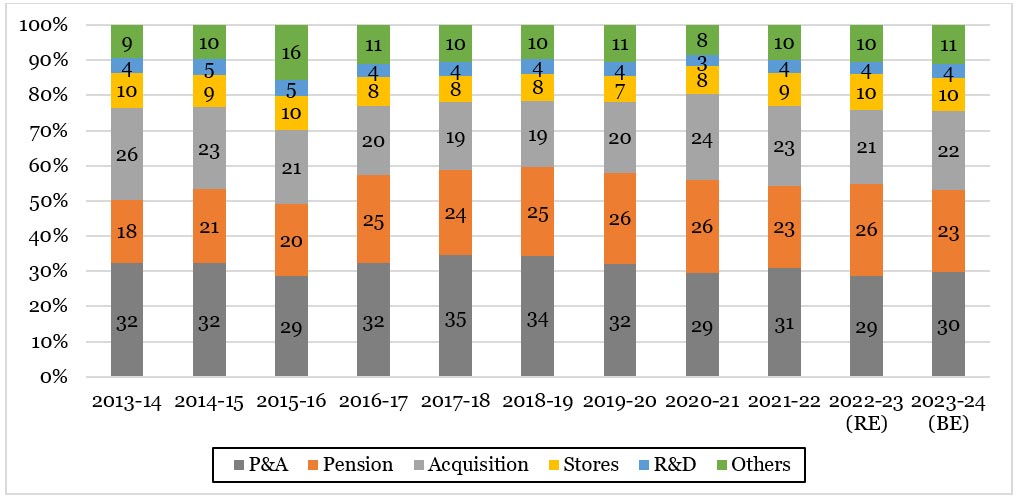

The growing economic heft over the years has given a boost to India’s military spending, which has risen to become the fourth largest in the world, as of 2022.[8] In the last 10 years, MoD’s expenditure has more than doubled, albeit with a highly uneven annual growth (Figure 1).

Figure 1. MoD’s Expenditures and Growth

Note: Figures for 2023-24 and 2024-25 are revised estimates and budget estimates, respectively.

Source: Union Budget (relevant years)

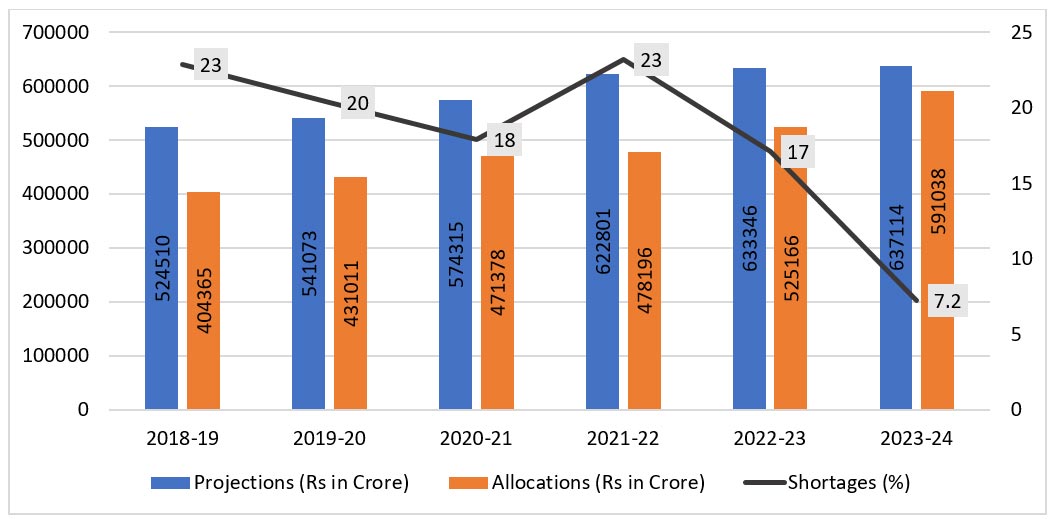

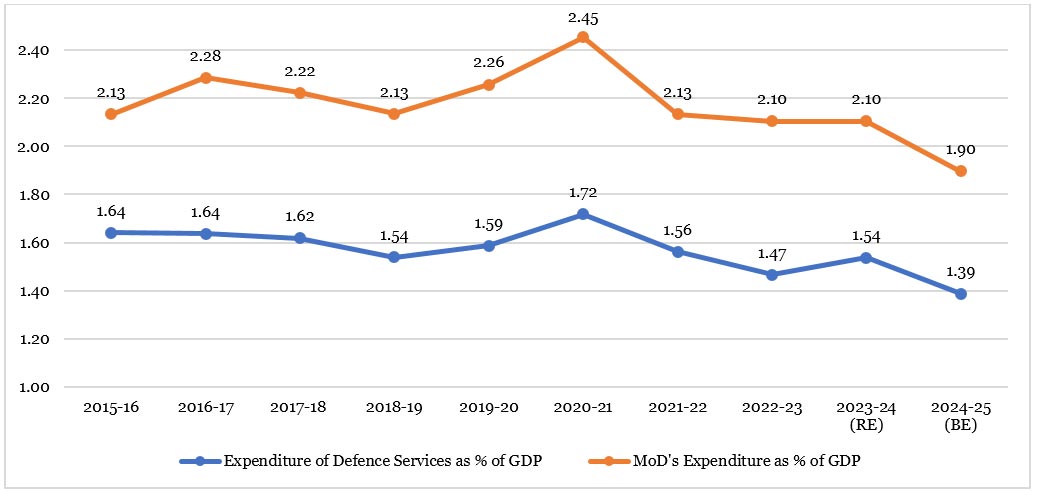

The increase in the MoD’s budget, however, has not been enough to meet all the projected requirements of the Indian armed forces, and there remain gaping annual shortages. As Figure 2 illustrates, except for 2023-‘24, in five other years, the annual shortages have been in the range of 17-23 percent. The sudden decline in shortages in 2023-‘24 is not necessarily due to hefty enhancements in budgetary allocations in that year, but rather because of the suppression of resource projections. Suffice it say that the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war has affected certain Russian supplies, particularly for the air force, which was forced to cut back on its projected resource requirements.[9]

Figure 2. Resource Constraints for India’s Ministry of Defence

Source: Standing Committee on Defence, Demands for Grants 2023-24[10]

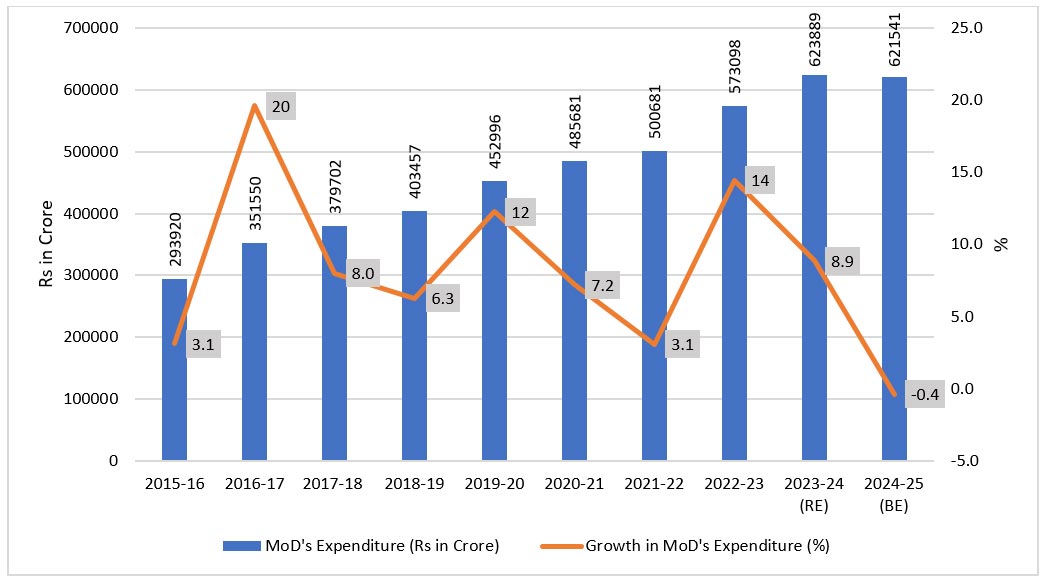

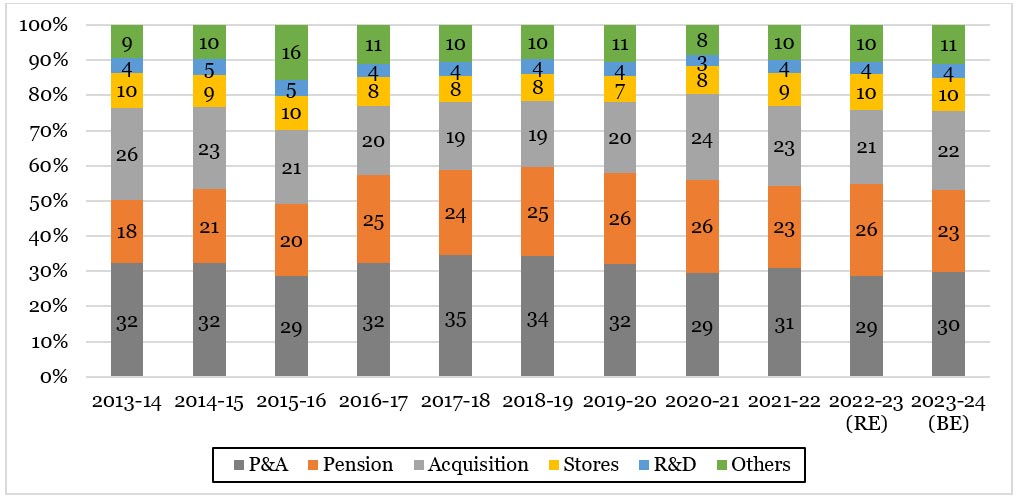

Aggravating the resource shortages further is that the Indian defence economy has long been constrained in managing its resources efficiently. A key issue is the mammoth cost of personnel. As Figure 3 shows, the direct personnel cost—pay and allowances (P&A) and pensions—takes not just an oversized share in the MoD’s resources, but it has also increased over the years. The rising share of personnel cost has come at the expense of those of modernisation and Stores (the latter caters to repair, maintenance and operational cost of the equipment in inventory), impacting the combat potential of the defence forces.

Figure 3. Distribution of MoD’s Expenditure

Source: Author’s own, based on Defence Services Estimates (relevant years) and Union Budget (relevant years)

The Modi government has taken efforts to correct the imbalance in MoD’s budget and improve the combat capability of the armed forces. The Agnipath scheme, for one, announced in June 2022, is a long overdue measure in this respect to contain the rising personnel cost.[11] Furthermore, through the ‘Make in India’ initiative and Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan, the government has made a serious attempt to revitalise the domestic arms manufacturing base to reduce dependency on other countries on critical arms.[12] As discussed later in this brief, the interim budget 2024-‘25 has gone a step further to improve India’s defence innovation ecosystem.

Growth Drivers of MoD Budget

Of the total interim allocations for the MoD, the biggest portion—73 percent or INR4,54,773 crore (US$54.7 billion)—is accounted for by the defence services which include three armed forces, the erstwhile Ordnance Factories (which were converted into seven Defence Public Sector Undertakings in October 2021) and the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) (see Table 1 and Annex). The defence services, like the two other segments of the MoD’s budget—MoD (Civil) and Defence Pensions—have also retained their previous share in the new allocations. Of MoD’s total allocations, 71 percent (INR4,39,300 crore) is earmarked for revenue expenditure and 29 percent (INR1,82,241 crore) capital expenditure.

A notable feature of the MoD’s budget figures is that the revised allocation for 2023-‘24 is higher than the budget estimates. Of the total increase of INR30,351 crore in the revised estimate, defence services have contributed INR23,177 crore, defence pensions INR3,890 crore, and MoD (Civil) INR3,284 crore. However, the increase in the defence services is entirely in its revenue segment, with the Stores budget of the air force having increased by a hefty 69 percent (or INR11,859 crore) to INR29,060 crore. The capital expenditure of the defence services, meanwhile, has declined by INR5,372 crore from INR1,62,600 crore to INR1,57,228 crore. About 50 percent of the decline is due to underspending on the modernisation front.

Table 1. MoD Budgets 2023-‘24 and 2024-‘25, Key Components

|

MoD (Civil) |

Defence Pensions |

Defence Services |

MoD Total |

| 2023-24 (BE) (in INR crore) |

22,613 (4%) |

1,38,205 (23%) |

4,32,720 (73%) |

5,93,538 (100%) |

| 2023-24 (RE) (in INR crore) |

25,897 (4%) |

1,42,095 (23%) |

4,55,897 (73%) |

6,23,889 (100%) |

| 2024-25 (BE) (in INR crore) |

25,563 (4%) |

1,41,205 (23%) |

4,54,773 (73%) |

6,21,541 (100%) |

| % Increase in 2023-24 (RE) over 2023-24 (BE) |

15 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

| % Increase in 2024-25 (BE) over 2023-24 (RE) |

-1.3 |

-0.6 |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

| % Increase in 2024-25 (BE) over 2023-24 (BE) |

13.0 |

2.2 |

5.1 |

4.7 |

Source: Author’s own, based on Union Budget 2024-25.

Note: BE is Budget Estimates, and RE is Revised Estimates; Percentage figures in parentheses show the respective shares in MoD’s total.

Although the increases in the revised estimates are significant, they do not fully meet the projected requirements of the MoD, which, as mentioned earlier, has been facing consistent shortages of resources to meet its planned expenditures. A 4.7-percent increase in the interim allocation would not bridge the shortages.

Table 2 summarises the contributions of various elements to the overall increase (of INR28,003 crore) in the MoD’s latest budget. It can be seen that the revenue component of the MoD’s budget or that of the defence services have a larger contribution. About 30 percent increase in revenue expenditure of the MoD is on account of pay and allowances (P&A) of the armed forces alone, which has increased to INR1,62,515 crore. Together with INR5,979 crore provided for under the Agnipath Scheme, the P&A of the armed forces represents 37 percent of the defence services’ budget and 27 percent of the MoD’s budget.

Table 2. Contribution to MoD’s Budget Hike

|

Contribution to MoD’s Budget Growth (in INR crore) |

Contribution to MoD's Growth (%) |

| MoD's Revenue Expenditure |

17,137 |

61 |

| MoD's Capital Expenditure |

10,866 |

39 |

| Defence Pensions |

3,000 |

11 |

| MoD (Civil) |

2,951 |

11 |

| Defence Services |

22,053 |

79 |

| Revenue Expenditure of Defence Services |

12,653 |

45 |

| Capital Expenditure of Defence Services |

9,400 |

34 |

| P&A of Armed Forces* |

9,770 |

35 |

| Stores of Armed Forces^ |

-910 |

-3.2 |

| Capital Acquisition$ |

7,277 |

26 |

Note:*: Inclusive of Agnipath Scheme; ^: Inclusive of Repair and Refit (R&R) of navy; $: Approximate

Source: Author’s own, based on Union Budget 2024-25

Of the total increase in MoD (Civil) budget, over 50 percent (or INR1,500 crore) is on account of the enhanced capital allocations for the Border Roads Organisation (BRO).[13] The BRO’s budget hike is part of the government’s focus on development of key border infrastructure in view of the “continued threat perceptions faced at the Indo-China border.”[14] The MoD has emphasised that the BRO’s additional allocation will fund the development of several strategic projects including the Nyoma Air Field (situated at an altitude of 13,700 feet) in Ladakh, Shinku La tunnel in Himachal Pradesh and the Nechiphu tunnel in Arunachal Pradesh, among others. A part of the allocation will also be used for providing a “permanent bridge connectivity to southernmost Panchayat of India in Andaman and Nicobar Island.”[15]

Share of the Defence Services

Unlike the past budgets, the interim budget for FY24-25 does not show the distribution of crucial capital expenditure among the branches of the armed forces, even though the service-wise revenue expenditure has been maintained. The MoD has justified this break from past practice on the ground of fostering “jointness among the services by consolidating the demand of the three services into similar items of expenditure.”[16] The MoD also argues that the consolidation “will bring flexibility in financial management by enabling the MoD to reappropriate the fund among the three services keeping in view the inter services priority [and] expedite decision making and ensure better utilization of the capital budget.”[17]

While this argument has certain merits, it is short of being convincing. The budget document is meant to set the priority of major allocations for vetting by the Indian Parliament, which has the right to know if a capability—say, coastal air defence—is better to be given to the Indian navy or the air force. By aggregating the capital allocations of the three services under broad items of expenditure, it hides the capability development plan of the services. It also obstructs the estimation of service-wise shares of defence forces in the defence budget—a key indicator keenly watched by many defence and military strategists. Nor does it show in good light MoD’s defence planning and procurement mechanism that is supposed to prioritise its service-wise planned capital spend much before the allocations are asked for from the Ministry of Finance (MoF).

Impact on Modernisation

The modernisation (also known as capital acquisition) budget was also allocated marginal increase. As seen in Table 3, the overall modernisation budget of the three forces has grown by 5.5 percent. Furthermore, the marginal increase comes after the downward revision of previous allocation by INR2,661 crore (2 percent), indicating that the capability accretion has fallen short of the intended plan.

Table 3. Modernisation Budget of the Armed Forces

| Modernisation Head |

2023-24 (BE) (in INR crore) |

2023-24 (RE) (in INR crore) |

2024-25 (BE) (in INR crore) |

% Increase in 2023-24 (RE) over 2023-24 (BE) |

% Increase in 2024-25 (BE) over 2023-24 (BE) |

| Aircraft and Aero Engines |

28,222 |

24,113 |

40,778 |

-14.6 |

44.5 |

| Heavy and Medium Vehicles |

4,038 |

2,716 |

4138 |

-32.7 |

2.5 |

| Other Equipment |

67,023 |

71,302 |

62,343 |

6.4 |

-7.0 |

| Rolling Stock |

163 |

200 |

150 |

22.7 |

-8.0 |

| Rashtriya Rifles |

100 |

136 |

195 |

36.0 |

95.0 |

| Joint Staff |

1,839 |

1,396 |

1,353 |

-24.1 |

-26.4 |

| Naval Fleet |

24,200 |

24,445 |

23,800 |

1.0 |

-1.7 |

| Naval Dockyard / Projects |

6,725 |

5,340 |

6,830 |

-20.6 |

1.6 |

| Total |

1,32,309 |

1,29,648 |

1,39,587 |

-2.0 |

5.5 |

Source: Union Budget 2024-25

Notwithstanding the marginal growth in the new allocations for modernisation, the MoD has argued that it is “in line with the Long-Term Integrated Perspective Plan (LTIPP) of the three services” and good enough to facilitate the armed forces to equip themselves with “state-of-the-art, niche technology lethal weapons, Fighter Aircraft, Ships, Platforms, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, Drones, Specialist Vehicle etc.”[18] Some specific big-ticket procurement that the new allocations will be used for, include Su-30 and LCA MK-I IOC/FOC fighters, C-295 transport aircraft, and new engines for MiG-29 fighters. An important procurement that is likely to be funded include MQ-9B drones and associated equipment (worth US$3.9 billion) for which the US State Department has recently made a decision for a possible export through the Foreign Military Sale (FMS) route.[19]

Following the finance minister’s Budget Speech, the MoD has remained silent on the issue of procurement from the domestic industry. For the past several years, the MoD had been indicating the share of modernisation budget to be spent on procurement from the domestic industry, with the share for 2023-24 being raised to 75 percent. In the absence of a new target, stakeholders in the domestic industry will need to know if the MoD has a long-term plan for domestic procurement or the previous ones were merely ad-hoc announcements.

<em>Atmanirbharata</em></strong><strong> in Defence

In an attempt to expedite atmanirbhrata in defence, the finance minister announced the launch of a new scheme for “strengthening deep-tech technologies for defence.”[20] The announcement followed another one by the FM to establish a “corpus of rupees one lakh crore…with fifty-year free loan.” The corpus, the FM elaborated, “will provide long-term financing and refinancing with long tenors and low or nil interest rates;” and “encourage the private sector to scale up research and innovation significantly in sunrise domains.”[21]

Both announcements of the FM are likely to encourage the private sector to mark a presence in India’s innovation ecosystem which has historically been dominated by government-owned research institutes. In the defence sector, the DRDO has a near-monopoly on R&D with the industry, barring few public sector entities, contributing little to innovation.[22] The government-led innovation system that India has followed since independence is in stark contrast to the industry-led innovation in countries that are more technologically advanced.[23]

To bring the industry, especially the private sector, to the forefront of defence innovation, the MoD in the last 10 years has made several efforts. These include the launch of new schemes such as Innovation for Defence Excellence (iDEX) and Technology Development Fund (TDF), and a simplified ‘Make’ guidelines. While these schemes and guidelines have attracted many players, especially the start-ups and small and medium enterprises, the innovations have yet to touch big weapons systems or major platforms.

Two years ago, the finance minister’s 2022-‘23 budget announcement of reserving 25 percent of defence R&D for the academia, industry and startups, was a big incentive for design and development of major systems by the private players.[24] Following the FM’s R&D announcement, the MoD followed up by identifying several big projects, the design and development of which was to be taken up by the industry. However, the identified projects have yet to progress because of lack of clarity if the FM’s announcement meant 25 percent of DRDO’s entire budget or a portion of the organisation’s revenue budget that it spends on external agencies for carrying out R&D through grants-in-aid. Suffice it to say that the latter category has little funds available (INR865 crore in 2024-25), and is unlikely to spur big-ticket innovation, which requires far greater financial support.

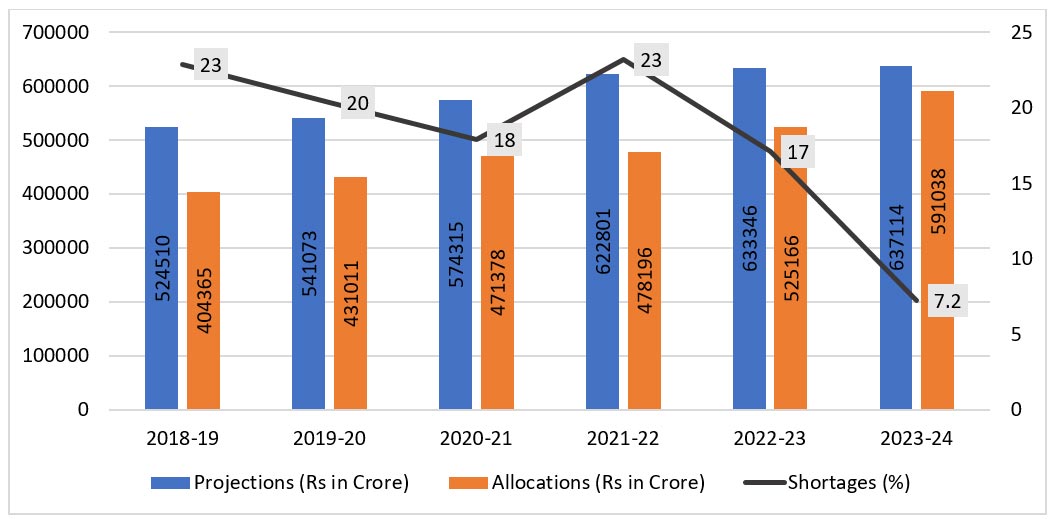

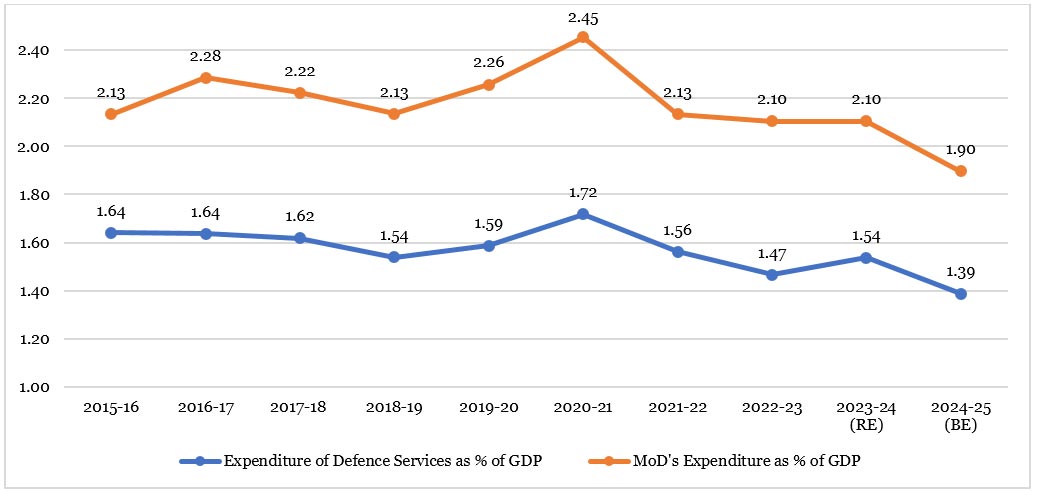

Defence as Share of GDP

It is undeniable that the expenditure of the defence services or of the MoD as a percentage of the GDP has not only remained modest but has in fact declined over the last several years (see Figure 5). This has raised concerns among both Parliamentarians and security experts, who have called attention to the need to peg defence spending to 3 percent of GDP.[25] Such a demand resonates with the promise made by former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who in 2005 declared the government’s willingness to allocate “3% of our GDP for our national defence.”[26] The call also resonates with many countries promising to raise their defence expenditure to a certain percentage of the GDP. For Instance, a number of countries of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) have agreed to spend at least 2 percent of GDP on defence.[27] Japan, which has historically pegged its defence budget to 1 percent of GDP, also plans to increase the share to 2 percent by 2027.[28]

Figure 5. Expenditure of Defence Services and MoD as % of GDP

Source: Union Budget and Economic Survey (various years).

Should India peg its defence budget at, say, 3 percent of GDP, as suggested by the Indian Parliamentarians and security experts? The answer lies in understating the politics and statistics of the GDP-to-defence ratio. The NATO countries’ decision is largely because of the US prodding of alliance member countries which successive US administrations perceive to be underspending on their national defence and thereby undermining the collective defence of the alliance. The understanding is that an increase in defence spending by each and every member will generate more resources which the alliance members could devote for acquiring new capability. The member countries’ commitment to collective defence is being assessed on the basis of the GDP-to-defence ratio.

The answer to the question of whether India should emulate NATO or Japan and fix its defence spending at a certain percentage of GDP is not straightforward for various reasons. First, GDP is not a kitty at the disposal of the government. What is at the disposal of the governments is a fraction of the country’s GDP that comes to the exchequer through various tax and non-tax revenues. Among all the sources of revenues, tax revenue is the real strength of a government’s purse. However, unlike many advanced countries or several emerging market economies, tax-to-GDP ratio in India is smaller (at 17 percent, compared to average of 34 percent in countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development or OECD).[29] This limits the government’s overall capacity as to how much it can spend without resorting to large-scale borrowings.

Second, a fixed GDP-to-defence ratio is practically unattainable as figures for both GDP and defence expenditures are revised several times at least three years before the final figures are ascertained.[b] To maintain a fixed ratio, the government has to change the defence expenditure as and when the GDP figures are revised, which is impractical, to say the least.

Third, it is undeniable that defence needs more resources than it is currently being allocated. That does not mean, however, that the current shortages can only be bridged by maintaining a fixed GDP-to-defence ratio; there is no guarantee that the ratio will lead to more resources, as assumed as gospel truth by some security experts. A contraction of GDP in a year, as it happened in India in 2020-21, would mean less resources for defence in that year than allocated previously.

Thus, the only possible way to address the current shortages being faced by the defence establishment is through raising the spending, irrespective of its share in GDP. However, raising the spending on defence beyond what the government in power allocates is a difficult task. A greater allocation for one sector comes at the cost of others; this is the hard reality that the defence establishment has to live with.

Conclusion

Given the fast-deteriorating global geopolitical environment and the security challenges at the Indo-China border, a 4.7-percent increase in MoD’s interim allocation would appear sorely inadequate. However, the defence establishment could take solace that the government has been raising the resource mid-year as it has done in the present fiscal year by revising upward the initial allocation by INR30,351 crore, a large portion of which is meant to meet the enhanced Stores requirement of the air force. A further mid-year increase in the new allocations, if required, cannot be discounted, especially given that the Indian economy is on a stronger footing.

The MoD needs to improve its planning and procurement apparatus to spend its allotted budget in a timebound manner. The surrender of previously allotted funds meant for modernisation not only hampers planned capability accretion of the armed forces but also shows the deficiencies in the existing system.

By clubbing the capital budgets of the armed forces, the MoD should not shirk from its responsibility of developing a balanced capability across the armed forces. It may consider to revert to the previous budgeting system where the capital allocations were distinctly provided under each of the armed forces.

The changing nature of war warrants that the MoD outline a plan to create surge capacity within the industry to quickly ramp up production of essential war equipment to meet any exigencies that may push the country to a long and protracted war. To complement the FM’s deep-tech scheme and the larger self-reliance drive, the MoD may also indicate how much of its latest procurement budget it wants to spend on the domestic sources. It will also help assess the progress being made under the Make in India initiative and Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan.

Annexure: Know Your Defence Budget

| Indicator |

2023-24 |

2024-25 |

| MoD’s Budget (INR crore) |

5,93,538 |

6,21,541 |

| Growth of MoD’s Budget (%) |

13 |

4.7 |

| Defence Services Budget (INR crore) |

4,32,720 |

4,54,773 |

| Growth of Defence Services Budget (%) |

12 |

5.1 |

| Defence Pensions (INR crore) |

1,38,205 |

1,41,205 |

| Growth of Defence Pensions (%) |

13 |

2.2 |

| MoD (Civil) Budget (INR crore) |

22,613 |

25,563 |

| Growth of MoD (Civil) Budget (%) |

13 |

13 |

| Revenue Expenditure of MoD (INR crore) |

4,22,163 |

4,39,300 |

| Growth of Revenue Expenditure of MoD (%) |

16 |

4.1 |

| Capital Expenditure of MoD (INR crore) |

1,71,375 |

1,82,241 |

| Growth of Capital Expenditure of MoD (%) |

6.8 |

6.3 |

| Revenue Expenditure of Defence Services (INR crore) |

2,701,20 |

2,82,773 |

| Growth of Revenue Expenditure of Defence Services Budget (%) |

16 |

4.7 |

| Share of Revenue Expenditure in Defence Services Budget (%) |

62 |

62 |

| Capital Expenditure of Defence Services (INR crore) |

1,62,600 |

1,72,000 |

| Growth of Capital Expenditure of Defence Services Budget (%) |

6.7 |

5.8 |

| Share of Capital Expenditure in Defence Services Budget (%) |

38 |

38 |

| Capital Acquisition Budget (INR crore) |

1,32,301 |

1,39,587^ |

| Growth of Capital Acquisition Budget (%) |

6.3 |

5.5^ |

| Share of MoD Budget in GDP (%) |

2.0 |

1.9 |

| Share of MoD Budget in Central Government Expenditure (CGE) (%) |

13 |

13 |

| Share of Defence Services Budget in GDP (%) |

1.46 |

1.39 |

| Share of Defence Services Budget in CGE (%) |

9.6 |

9.5 |

| Share of Capital Expenditure of MoD in Central Govt’s Capital Expenditure (%) |

17 |

16 |

| GDP (INR crore) * |

296,57,745 |

327,71,808 |

| GDP Growth (%) * |

8.9 |

10.5 |

| CGE (INR crore) |

45,03,097 |

47,65,768 |

| Growth of CGE (%) |

14 |

5.8 |

| CGE as % of GDP |

15 |

15 |

| Fiscal Deficit (% of GDP) |

5.9 |

5.1 |

Note. *: GDP figures, in current market prices, for 2023-24 and 2024-25 are first advance estimates (FAE) and budget estimates (BE), respectively; ^: Approximate figure.

Endnotes

[a] The conversion to US$ is based on the average exchange rate (in January 2024) of $1.0 =Rs 83.10.

[b] India’s defence spending is presented in the form of budget estimate, revised estimate and actual expenditure. The figures in these three forms are not necessarily the same.

[1] Ministry of Finance, Interim Budget 2024-25, https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/.

[2] For a comprehensive analysis of India’s previous defence allocations, see Laxman Kumar Behera, “High on Revenue, Low on Capital: India’s Defence Budget 2023-24,” ORF Issue Brief No. 614, February 2023, https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/ORF_IssueBrief_614_Defence-Budget.pdf.

[3] “Welcome to the new era of global sea power,” The Economist, January 11, 2024.

[4] Abhijit Singh, “Deciphering China-Pakistan naval exercises in the Indian Ocean,” ORF Expert Speak, November 20, 2023, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/deciphering-china-pakistan-naval-exercises-in-the-indian-ocean

[5] “Why Iran is hard to intimidate”, The Economist, February 06, 2024; Astha Rajvanshi, “Indian is walking a diplomatic tightrope in the Red Sea conflict,” Time, February 02, 2024.

[6] Harsh V Pant and Kartik Bommakanti, “Dynamic shift: Indian Navy in the Red Sea,” Business Standard, February 06, 2024.

[7] Ministry of Finance, The Indian Economy: A Review, January 2024, pp. 63-64.

[8] Nan Tian et al., “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2022,” SIPRI Fact Sheet, April 2023.

[9] Standing Committee on Defence, Demands for Grants 2023-24, 36th Report, p. 20.

[10] Standing Committee on Defence, Demands for Grants 2023-24, 35th Report, p. 9.

[11] Laxman Kumar Behera and Vinay Kaushal, “The Case for Agnipath,” ORF Issue Brief No. 567, August 2022, https://www.orfonline.org/public/uploads/posts/pdf/20230816161143.pdf

[12] For a review of India’s defence industry, see Laxman Kumar Behera, “The State of India’s Public Sector Defence Industry,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 419, October 2023, Observer Research Foundation.

[13] Ministry of Finance, Interim Union Budget 2024-25.

[14] Press Information Bureau, “Record over Rs 6.21 lakh crore allocation to Ministry of Defence in Interim Union Budget 2024-25,” February 01, 2024

[15] Press Information Bureau, “Record over Rs 6.21 lakh crore allocation to Ministry of Defence in Interim Union Budget 2024-25.”

[16] Press Information Bureau, “Record over Rs 6.21 lakh crore allocation to Ministry of Defence in Interim Union Budget 2024-25.”

[17] Press Information Bureau, “Record over Rs 6.21 lakh crore allocation to Ministry of Defence in Interim Union Budget 2024-25.”

[18] Press Information Bureau, “Record over Rs 6.21 lakh crore allocation to Ministry of Defence in Interim Union Budget 2024-25.”

[19] Defence and Security Cooperation Agency, “India—MQ9B Remotely Piloted Aircraft,” New Release, February 01, 2024, https://www.dsca.mil/sites/default/files/mas/Press%20Release%20-%20India%2024-07%20CN%20v3.pdf.

[20] Ministry of Finance, “Interim Budget 2024-25: Speech of Nirmala Sitharaman,” February 01, 2024.

[21] Ministry of Finance, “Interim Budget 2024-25: Speech of Nirmala Sitharaman.”

[22] For a review of India’s innovation system, See Laxman Kumar Behera, “Examining India’s defence innovation performance,” Journal of Strategic Studies, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2021.1993829.

[23] Laxman Kumar Behera, “Defence Innovation in India: The Fault Lines,” IDSA Occasional Paper No. 32, 2014, P. 16, https://www.idsa.in/system/files/OP_DefenceInnovationInIndia.pdf.

[24] Ministry of Finance, “Budget 2022-23: Speech of Nirmala Sitharaman”, February 01, 2022.

[25] For a detailed discussion on GDP-Defence debate see Laxman Kumar Behera, India’s Defence Economy: Planning, Budgeting, Industry and Procurement (Routledge: Oxon, 2021), pp. 53-68.

[26] PM Manmohan Singh’s indication for higher GDP for defence was however conditioned on 8% growth of Indian economy. Press Information Bureau, “PM addresses Combined Commanders’ Conference,” October 20, 2002.

[27] “NATO allies to spend 'at least 2%' of GDP on defence, diplomats say,” Reuters, July 08, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/nato-allies-agree-spend-at-least-2-their-gdp-defence-diplomats-2023-07-07/

[28] “Japan set to increase defense budget to 2% of GDP in 2027,” Nikkei Asia, November 28, 2022, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Japan-set-to-increase-defense-budget-to-2-of-GDP-in-2027#:~:text=TOKYO%20%2D%2D%20Prime%20Minister%20Fumio,the%20year%20starting%20April%202027.

[29] Ministry of Finance, Economic Survey 2015-16, Vol. I, p. 108.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV