-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Anubha Bhonsle et al., Empowering the Global South: G20 Presidencies of Key Emerging Economies in a Shifting World Order, October 2023, Observer Research Foundation.

This report adopts an interdisciplinary approach. Primary data collection involved interviews with experts in diplomacy, policymaking, international relations, global macroeconomics, health, climate change, digital economy, food and agricultural security, and gender equity. Secondary research included an extensive literature review of policy papers, G20 knowledge products and official documents, academic journals, research articles, reports from international organisations, government leaders’ speeches, and reputable news sources.

The report draws on the institutional expertise of Global Health Strategies and Observer Research Foundation in delivering high-quality research and analyses across health and development, security, strategy, economy, energy, and environment, among other issues.

In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, global efforts are underway to reshape and reconstruct existing structures, leading to a discernible shift in outlook on many geopolitical matters. There is a pronounced focus on global public goods,[1] climate change mitigation, digital technology and privacy, agriculture and food security, global health, and financial stability. These issues, with the potential to impact many nations, often converge, producing ripple effects that transcend borders. Addressing these global public goods necessitates collaborative solutions, signifying a move towards a more interconnected and multipolar world order.

This shift is apparent in the growing significance of the G20 in comparison to the G7, from which the former draws inspiration. Unlike the G7, the G20 is more heterogenous, and such diversity has elevated it as a primary forum not only for international economic cooperation but also for shaping responsive solutions to global challenges. The decisions made by the G20 carry immense weight, with its member nations accounting for nearly 80 percent of the world’s population, 88 percent of GDP, and 79 percent of global trade.[2]

By gathering the wealthiest nations in the same platform with emerging economies, and making consensus a cornerstone of decision-making, the G20 provides an inclusive, and potentially equitable, framework for setting global agendas and renewing public confidence in multilateral institutions. The impact of G20-driven benefits is contingent to a large extent on the influence exerted by developing countries. In this context, the growing significance in the global order of four emerging economies—Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa—cannot be overlooked. These regional powerhouses serve as a bulwark against diverse challenges, whether economic or political.

These four countries epitomise, in principle and essence, the Global South—a categorisation that is more geopolitical than geographic. While indeed they exhibit some degree of cartographic coherence, these countries also share historical, economic, and political commonalities.

“For the first time in the history of G20, the troika is with the developing world... This troika can amplify the voice of the developing world, at a crucial time when there are increased tensions due to global geopolitics.”[3]

-Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India

Against this backdrop, this report examines the significance of consecutive G20 Presidencies of emerging economies: Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa. It argues that these successive presidencies present a historic opportunity to bring to the forefront the perspectives of the Global South while spearheading efforts to tackle global challenges, including a looming economic recession, the conflict in Ukraine,[a] the climate crisis, and the deceleration of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Agenda post-COVID-19. By leveraging the G20 platform, these nations have the capacity to advocate for policies that align with their shared interests, fostering increased multilateral cooperation. Their successive Presidencies provide these emerging nations with an extended timeframe to collectively shape global agendas.

The report discusses the past, present, and potential future efforts of each of the four Presidencies in advancing select goals that impact the SDG Agenda. It will also address key challenges faced by the Global South and outline recommendations to ensure the continuity of development interventions.

“Because developing countries have had enough…Enough of paying for a climate crisis they did nothing to cause. Enough of sky-high interest rates and debt defaults. And enough of life-and-death decisions about their people that are taken beyond their borders, without their views and their voices.”[4]

-António Guterres, United Nations Secretary General

In May 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the end of the global health emergency posed by COVID-19.[5] However, the shift to a “new normal” was disrupted by the Ukraine conflict, triggering fresh food and energy crises.[6]

Massive challenges are persisting, including inflation, rising cost of living, widespread hunger, capital outflows from emerging markets, and geopolitical tensions. These are being compounded by ‘new’ global risks, such as unsustainable debt levels, slow economic growth, and the escalating impacts of climate change, further complicated by a shrinking window to limit warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.[7]

The fallout of the pandemic disproportionately affected the Global South, who had less access to resources. A number of studies have found that low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) bore a disproportionate burden of the ramifications of the pandemic.[8],[9] Vaccine inequity is a stark example, exacerbated by distribution challenges, supply chain disruptions, and geopolitical considerations. A 2022 study revealed that 77 percent of individuals in high- and upper-middle-income countries completed the initial COVID-19 vaccination course, while the equivalent share for LMICs stood at 50 percent, approximately 1.5 times lower.[10]

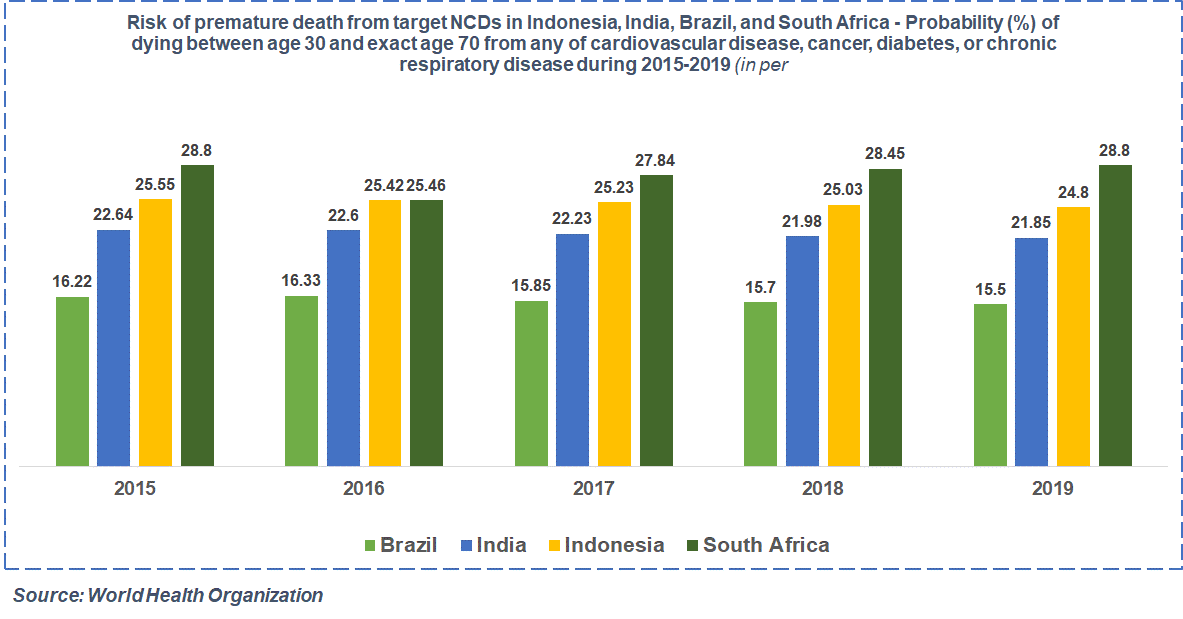

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs)—responsible for 41 million deaths annually or 74 percent of the global death toll—have perennially posed a serious obstacle to achieving public health goals. A 2022 WHO report[11] has highlighted that between 2011 and 2030, the cost of lost productivity from the four major NCDs is estimated at a staggering US$30 trillion, increasing to US$47 trillion when considering mental health. The report underscores that millions of people, especially in low-resource settings, are unlikely to access the necessary prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care needed to delay or prevent NCDs and their consequences. Over 70 percent of all NCD deaths occur in LMICs.[12] Achieving SDG 3.4 (Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health) in LMICs would require an additional US$18 billion annually, totalling US$140 billion by 2030.[13]

Fig. 1: Risk of Premature Deaths from Target NCDs in Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa

Source: World Health Organisation[14]

Source: World Health Organisation[14]

The adverse effects of climate change, including the phenomenon of El Niño[15]—or the unusual warming of surface waters in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean—can impact weather worldwide. It poses additional threats to agriculture and food security across LMICs in the post-pandemic world. The World Economic Forum, in its 2023 report, predicts disruptions in palm oil and rice production in countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. In India, too, food security is threatened by climatic anomalies.[16]

Against this backdrop, the G20 whose strength lies in global policy coordination, assumes a pivotal role. The G20’s emphasis on interconnectedness, recognising the complex links between economic, social, environmental, and political factors, provides a comprehensive approach to decision-making. Its significance is heightened as it navigates global crises under the successive leaderships of the four emerging economies. This presents an inflection point in the G20’s history, allowing voices from the Global South to construct a meaningful narrative around their individual development journeys and the strategies needed to address endemic and borderless challenges.

The consecutive Presidencies also provide an opportunity to underscore the five core principles of South-South cooperation within the global development agenda: respect for national sovereignty; national ownership and independence; equality; non-conditionality; non-interference in domestic affairs; and mutual benefit. This affords emerging economies the unique opportunity to articulate their current concerns, policy imperatives, and governance priorities with a unified perspective.

With emerging economies in leadership roles, the G20 is ideally positioned to facilitate South-South and South-North sharing of knowledge, ideas, technologies, and services, demonstrating that the most efficient path to sustainable development involves Southern countries engaging fruitfully with the global economy.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the global pursuit of the SDG Agenda just as the UN-designated Decade of Action (2020-2030) began. A recent assessment of the 17 SDGs and their 140 sub-targets found that only 12 percent of these goals are on-track, close to half are moderately or severely off-track, and around 30 percent have seen either no movement or regression below the 2015 baseline.[17]

Much of this setback is attributed to the inadequate allocation of investment and financial resources. The annual financing gap for SDGs is at least US$4 trillion, with a substantial portion concentrated in the Global South.[18] Compounding this financial disparity is that the Global South is often compelled to divert limited resources to counteract negative spillovers of the Global North’s activities,[19] further impeding progress on the SDGs in the region.

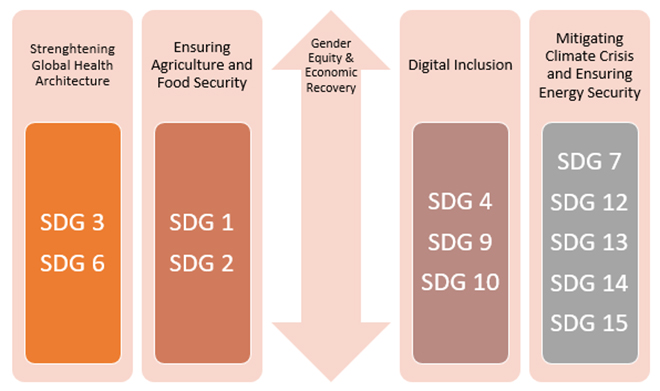

The primary focus of multilateral cooperation should be on addressing tangible hardships faced by ordinary people, including strengthening the global health architecture and ensuring agriculture and food security. The second focus pertains to longer-term considerations of building forward better, such as digital inclusion and mitigating the climate crisis while promoting energy security. Amidst these, gender equity and economic recovery are cross-cutting themes requiring attention to address systemic inequalities and promote sustainable development. If effectively addressed by the G20, these goals can directly contribute to progress on at least 12 of the 17 SDGs, creating momentum towards achieving the 2030 Agenda.

Fig. 2: Key Focus Areas and Related SDGs

These focus areas serve as pathways through which the Global South’s advantages, good practices, perspectives, and resilience can be leveraged. These include crisis- and disease-management experience, rich agricultural resources, emerging market dynamism, a culture of innovation, adaptable and scalable solutions, low transaction and implementation costs, speed of service and project delivery, and multi-stakeholder approaches.[20]

Each of the four Global South countries leading the G20 between 2022-26 has its own strengths. Indonesia, with its diverse economy and strategic geographic location, bridges Asia and the Pacific. India boasts dominance in the domains of Information Technology and pharmaceuticals, and is one of the world's most resilient economies. Meanwhile, Brazil leads in agriculture, making a significant contribution to global food production. South Africa, for its part, is home to rich mineral resources and a well-developed financial sector, and has unique access to the G20's newest member—the African Union, representing the world’s most vulnerable countries.

In essence, the G20, under the extended leadership of the Global South—especially Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa—holds the potential to make strides in achieving the SDGs and fostering a more interconnected and resilient global community.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in the global health infrastructure, resource availability, and emergency preparedness—across both developed and developing nations. Disruptions in essential health services led to far-reaching consequences, from setbacks in addressing malnutrition to the resurgence of preventable diseases like measles.[21] Persistent challenges in programme delivery, including growing antimicrobial resistance (AMR), continue to hinder efforts to eradicate diseases such as tuberculosis (TB).

The cross-border spread of diseases became an even more stark reality, with WHO consistently highlighting the heightened risks of future viral outbreaks amid worsening climate change.[22] A crucial and urgent focus is to address fragmented healthcare systems which, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 crisis, resulted in disjointed care and posed numerous issues for patients and healthcare providers. The unavailability of crucial drugs, pricing issues, global and unequal disruptions in the supply chain, and overburdened human resources brought attention to stark inequities in affordability and access to quality care—a fundamental aspect of Universal Health Coverage (UHC). To strengthen healthcare systems for future crises, a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach is vital, grounded in the principles of UHC and One Health.[b]

This strategy must specifically tackle gender disparities in healthcare, addressing access and disruptions in essential services for women. Many global efforts that significantly improved the health of mothers and newborns have stalled since COVID-19. New data[23] reveals the potential of scaling up global access to seven innovations and practices that can address the leading causes of maternal and newborn deaths, saving the lives of nearly 1,000 mothers and infants every day by 2030, particularly in South Asia, other LMICs, and sub-Saharan Africa.

Digital health solutions, including AI-powered ones, are becoming essential for efficient and last-mile care delivery. They can strengthen health systems by improving supply chains and workforce management, particularly in low-resource settings. A 2020 WHO report[24] illustrates its

significance, especially in managing pandemics, by outlining digital health emergency responses and proposed actions. However, the digital divide in accessing these solutions remains a concern. Bridging the digital divide has been highlighted as a crucial step towards ensuring universal digital access to inclusive healthcare, aligning G20 countries with SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being). Global collaboration is critical to addressing data privacy concerns that arise out of these digital solutions and standardise cross-border policies. The G20, led by the digitally competitive members of the Global South, is well-placed to facilitate this.[25] Similarly, the grouping is in a unique position to lead discussions on sustainable and equitable financing for health at the global, regional, and national levels, as well as to facilitate knowledge sharing of best practices, learnings, and solutions that can enhance the resilience of global healthcare systems.

These components—UHC, digital health, sustainable finance, knowledge-sharing, and a strong gender lens—are key to strengthening the global health architecture, particularly in many Global South countries where female healthcare workers have been at the frontlines of the pandemic response and post-pandemic recovery.[26] Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa have directly or indirectly outlined many of these as priority areas for their G20 Presidencies.

The global temperature has risen by 1.1°C from pre-industrial levels, causing alarming shifts in weather patterns among them, surface heating, rising sea levels, severe droughts, wildfires, and floods.[27] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns that these pose the threat of irreversible damage to the planet, with widespread implications across sectors, from reducing poverty to health and agriculture.[28] Reports indicate that climate change could push 132 million people[29] into poverty by 2030 and cause 250,000 deaths between 2030 and 2050 due to malnutrition, malaria, diarrhoea, and heat stress.[30]

The impact of a hotter world beyond critical thresholds will be most acutely felt in LMICs. Despite their relatively smaller historical contributions to global greenhouse gas emissions, LMICs bear a disproportionate burden of the adverse impacts of climate change.[31] Small Island Developing States (SIDS) also face substantial risks, with the Caribbean alone witnessing climate change-induced damages amounting to US$12.6 billion annually.[32] Gender inequity exacerbates the vulnerability of women and girls in these regions, posing unique threats to their livelihoods, health, and safety.

Despite the G20’s commitment in 2009 to reform fossil fuel subsidies, aiming to eliminate ineffective ones while aiding the poorest populations, subsidies have increased.[33] In 2021, G20 nations provided US$190 billion in fossil fuel subsidies, up from US$147 billion in 2020,[34] driven by factors like rising oil and gas prices.

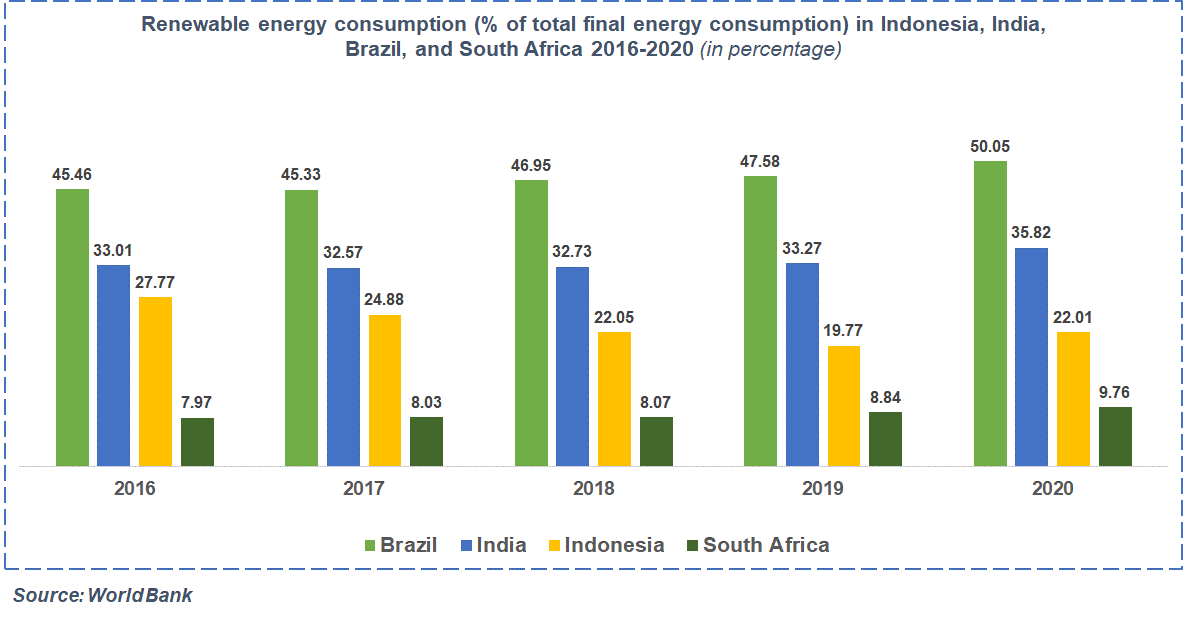

Decentralised renewable energy (DRE) technologies offer a pathway away from fossil fuels, particularly in emerging economies. However, climate finance remains a key piece to this puzzle, marked by funding gaps, allocation uncertainties, adaptation disparities, limited accessibility, and institutional challenges.

The G20’s nature of gathering both wealthy nations and emerging economies, and its influence on Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), positions the grouping as a critical driver for climate finance flows and systems reform. With emerging economies leading the group for four consecutive years, the G20 has a unique, extended window for equitable deliberations on aligning climate finance with the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ to reduce carbon emissions. A swift and just transition to clean energy, along with climate finance and reform, are focal points for the G20 Presidencies of Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa, within a larger agenda of coordinating an equitable approach to climate policy, sustainable infrastructure, and finance.

Fig. 3: Renewable Energy Consumption as Percentage of Total Energy Consumption in Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa

Source: World Bank[35]

The global reduction in poverty over the past two decades has yet to translate into balanced and inclusive development or shared prosperity. A recent report[36] reveals that 258 million people across 58 countries and territories faced acute food insecurity at crisis or worse levels in 2022, up from 193 million in 2021. This marks the most dire situation in the seven years since the first of this annual report was launched.

A growing gender gap exacerbates food insecurity, with women historically bearing a disproportionate impact of crises, including challenges related to food security and nutrition. The COVID-19 pandemic further widened this gap, impacting women’s economic opportunities and access to nutritious foods.[37]

Climate change has added to the challenges, with extreme weather events negatively affecting agricultural output and triggering crop losses, inflation, and food insecurity. The conflict in Ukraine has further impacted food imports and prices, particularly in populous G20 nations like Brazil and India.[38] Additionally, food wastage poses a significant problem, contributing to environmental degradation and economic losses. About one-third or 2.5 billion tons[39] of food produced is wasted or lost yearly, with a fiscal impact of around US$936 billion annually, potentially rising to US$1.5 trillion by 2030.[40]

The impact is more acutely felt in emerging economies compared to wealthier nations. With Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa leading the G20, there is an opportunity to bring to the forefront of food security conversations certain unique challenges—such as diverse diets—and crucial intersectionalities like those of the rights of small farmers and rural women. The focus for these four Presidencies, past, present and future, has and is likely to be, on increasing agricultural productivity while simultaneously building more sustainable, resilient, equitable, and efficient food and trade systems.

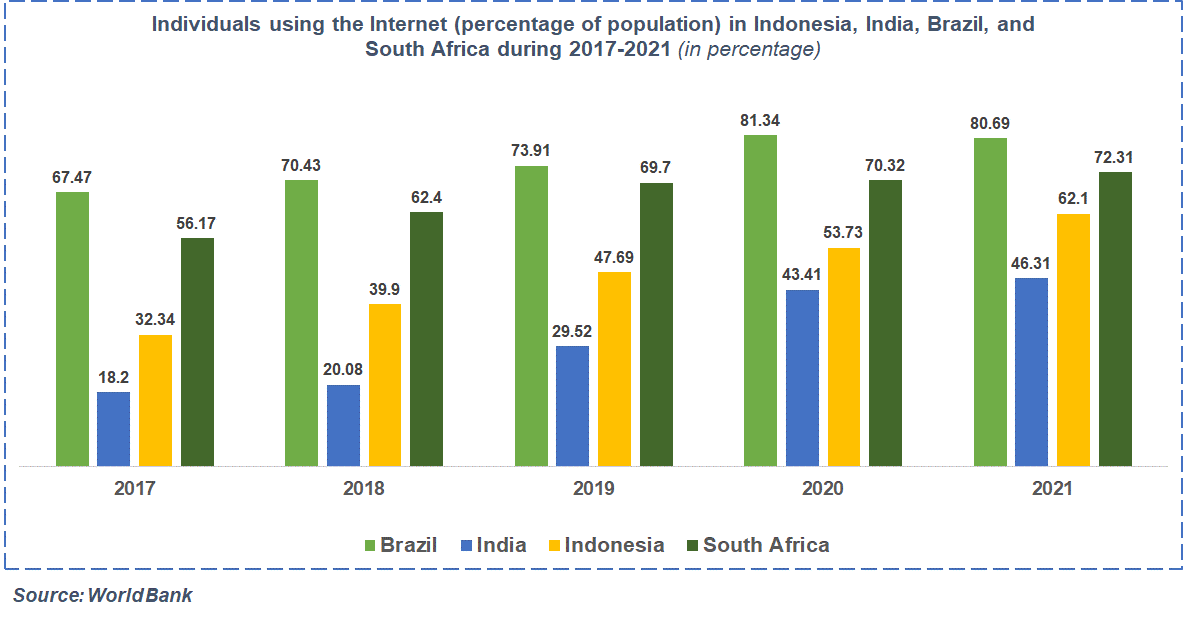

Digitalisation is increasingly becoming a key driver in global transformation and economic growth. Research estimates the value of the global digital economy at around US$11 trillion (15.5 percent of global GDP in 2016), projected to reach US$23 trillion (24.3 percent of global GDP) by 2025.[41] In 2021, mobile technologies and services contributed US$4.5 trillion of economic value added, or 5 percent of global GDP.[42] The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the pivotal role of digital technologies in mitigating disruptions and ensuring seamless access to services such as healthcare, banking, e-governance, and education, particularly during periods of mobility restrictions. By the end of 2021, mobile internet users reached 4.3 billion across the globe—a significant increase of approximately 300 million from the previous year.[43] A substantial portion of this increase came from LMICs.

The pandemic years prompted governments to maximise the benefits of Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) for the efficient delivery of economic opportunities and social services. However, regulatory compliance gaps, escalating cyber security and data privacy threats, and uneven access across geographies and genders impede progress.[44] For example, the last-mile delivery of financial services is expedited by the rise in mobile phone and internet usage. Yet, in India, just over half of women own and use a mobile phone, and less than one-fourth utilise them for financial inclusion.[45]

Fig. 4: Percentage of the Population in Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa, Who Use the Internet

Source: World Bank[46]

Amid these challenges, the G20 rightly prioritises quality, affordable, secure, accessible, and inclusive DPIs; the free flow of Data for Development (D4D), respecting policy and legal frameworks; and building user trust, privacy, data protection, and intellectual property rights.

Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa are ideal candidates to lead these conversations. Among the Global South, they are known for leapfrogging traditional infrastructure development and directly adopting digital technologies.[47] Their 'mobile-first' younger populations are generally more adaptable to new technologies and can drive innovation in the digital space. They also have relatively flexible regulatory environments, allowing them to experiment and innovate with digital service delivery. India is in a particularly good position to take the lead on this front. From its digital ID system of Aadhaar and health services management via Co-WIN, to its expansive payments infrastructure in the form of UPI—it can demonstrate and share its wealth of experience in building localised, inclusive digital solutions. At the same time, significant populations in the Global South are likely to be excluded, exploited, or marginalised if existing disparities in digital access, literacy, and capabilities are not addressed through multilateral cooperation on platforms like the G20.

In his remarks at the 2022 G20 Summit in Bali, European Council President Charles Michel described that year’s proceedings as “one of the most difficult ones that there have ever been.”[48] Pressures from the geopolitical tensions in Europe, a global economic downturn, escalating climate crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic required Indonesia to shape an agenda focused on inclusive recovery. Under the theme ‘Recovery Together, Recover Stronger’, Indonesia championed post-pandemic recovery and sustainable development[49] in the global health architecture, sustainable energy transition, and digital transformation.

In 2023, the challenges persisted during India’s G20 Presidency. Amidst mounting geopolitical disagreements, India positioned its leadership as crucial for collective action and multilateral initiatives. Prioritising a Global South agenda, India’s Presidency, themed “One Earth, One Family, One Future”, aimed to address challenges, build consensus, and deliver tangible results. The New Delhi G20 Leaders’ Summit Declaration, unanimously adopted, advocated for inclusive and resilient growth, progress on SDGs, green development and Mission LiFE, technological transformation and public digital infrastructure, reforming multilateral institutions, women-led development, and international peace and harmony.[50]

Indonesia’s and India’s Presidencies aligned efforts to fortify the global health architecture following the declassification of COVID-19 as a health emergency. Indonesia focused on enhancing global health system resilience, streamlining protocols, and expanding hubs for Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness, and Response (PPR).[51]

India then set its priorities around health emergency preparedness with a One Health approach, bolstering pharmaceutical cooperation for accessible medical countermeasures (vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics), addressing AMR, and promoting digital health for UHC.

Indonesia’s G20 Presidency achieved a milestone with The Pandemic Fund, a dedicated financial mechanism to proactively address pandemic threats. Initially proposed by The World Bank as the Financial Intermediary Fund (FIF) for Pandemic PPR in 2020-21, Indonesia secured commitments from 27 nations and entities, amassing an initial sum of US$1.4 billion[52] for the fund. In February 2023, the Fund’s Governing Board approved the allocation of US$300 million to developing countries to enhance their pandemic readiness. India's G20 Presidency sustained this with the inaugural Call for Proposals for the Pandemic Fund, underscoring the necessity to attract new donors and co-investments. Economic challenges and debt issues, however, have caused demand for funding to increase, surpassing initial pledges.[53]

During both Presidencies, the G20 collectively prioritised bolstering local and regional manufacturing capabilities and research networks to enhance the accessibility of vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics (VTDs), especially in resource-constrained settings. Indonesia facilitated an agreement with six other G20 countries—Argentina, Brazil, India, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey—to establish a collaborative centre for vaccine manufacturing, treatment, and diagnostics. As outlined in both the Bali and New Delhi Declarations, G20 members committed to reducing the timeframe for VTD manufacturing and distribution from 300 to 100 days while ensuring regulatory oversight, access, and affordability.[54]

India’s G20 Presidency further affirmed support for a comprehensive WHO-led consultative process to develop a mechanism of interconnected platforms leveraging local and regional R&D and manufacturing capacities. The goal is to improve access to safe, effective, quality-assured, and affordable VTDs, while enhancing last-mile delivery and contributing to the overarching goal of UHC.

Both the Indonesian and Indian Presidencies, along with the preceding one of Saudi Arabia, underscored the importance of digitising healthcare systems. India’s G20 Health Working Group committed to endorsing WHO’s Global Initiative on Digital Health (GIDH). This platform primarily aims to ensure equitable access to high-quality healthcare services and standardised health solutions and address the digital divide in global health. The initiative aligns with the WHO-endorsed Global Digital Health Strategy 2020-2025,[c] expanding ambitions related to health-focused SDGs, including achieving UHC. While funding for the GIDH secretariat[d] is expected from various sources, concerns about its long-term sustainability persist.

Across sub-agendas, the Indonesia- and India-led G20 recognised that a sustainable recovery and achieving UHC under the SDG 3.8 is only possible through a comprehensive, transdisciplinary, and cohesive One Health approach. Significant focus was placed on addressing the challenges posed by TB and AMR. Two ‘call to action’ documents were formulated—for financing for TB response and strengthening national AMR governance, stewardship, and infection prevention control. The significance of AMR, highlighted during Indonesia’s tenure, gained further prominence in New Delhi. G20 members endorsed research and development initiatives for new antimicrobial interventions. They also acknowledged ongoing negotiations within the International Negotiating Body (INB) framework, which holds the potential for addressing AMR within the ambit of WHO's regulations and tools, which includes the International Health Regulations (IHR) and Core Capacity Assessment Tool (CCAT). All of this signifies a vital opportunity to advance the discourse on AMR globally.

Crucially, G20 nations acknowledged the linkages between climate change and health crises, evident in the surge of emerging infectious diseases. The need for climate-resilient health systems was deeply acknowledged. Member nations endorsed the strategic alignment of organisations, including the quadripartite (World Health Organization, World Organisation for Animal Health, Food and Agriculture Organization, and United Nations Environment Programme), coupled with initiatives such as the Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health (ATACH) to strengthen proactive prevention, preparedness, and response to the interconnected climate and health challenges.

The potential of evidence-based Traditional and Complementary Medicine (T&CM) was a distinct facet of India’s G20 Presidency. The discourse focused on adherence to evidence-based approaches, aligning with WHO’s Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014-2023, now extended until 2025. Grounded in robust scientific validation, this framework forms the basis for incorporating certain T&CM practices into public health systems—a recognition significant for many cultures and regions, including in the Global South, where traditional medicine has been a part of healthcare for generations.

The far-reaching impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for global action on mental health. India prioritised mental health and psychosocial support, including the integration of human-centric mental health policies and training in workplaces and health systems. A G20 co-branded event in 2023 spotlighted initiatives like Tele-Manas, a no-cost tele-mental health service for youth, highlighting the importance of healthcare tailored for adolescents.

Amidst concurrent climate, energy, and geopolitical challenges, Indonesia prioritised the clean energy transition within the G20. The G20 Energy Transitions Working Group (ETWG) centred efforts on energy access, the expansion of smart and clean energy technologies, and the promotion of clean energy financing.

A noteworthy initiative addressing these challenges is the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) that fosters collaboration between developed and developing countries. The former contributes funding, technology, and capacity building to support the latter’s shift from coal to clean energy. Indonesia was among the early signatories. Co-led by the United States and Japan, JETP aims to facilitate an ambitious power sector transition in Indonesia. The goals include achieving net-zero emissions in the country’s power sector by 2050, ensuring that at least 34 percent of all power generation comprises renewable energy by 2030, and expediting the early retirement of coal-fired power plants.[55]

Indonesia’s advocacy culminated in the Bali Compact,[56] a set of nine voluntary principles guiding G20 countries towards clean, sustainable, just, and affordable energy transitions. Integrated into the 2022 G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration, the Bali Compact employs a whole-of-government approach to support inclusive energy transitions, covering decision-making frameworks, energy security, affordability, resilient infrastructure, energy efficiency, and collaboration on finance mobilisation. Indonesia also influenced recommendations in the G20 Sustainable Finance Report, prioritising affordability and accessibility while emphasising inclusive investments in sustainable energy.

When India assumed leadership, it introduced a layer of contextual challenges and priorities, maintaining a focus on an action-oriented, consensus-driven approach to address environmental and climate change issues. The Environment and Climate Sustainability Working Group highlighted cross-sectoral collaboration with other working groups and ministries. Member nations agreed on priority areas, including arresting land degradation, accelerating ecosystem restoration, protecting biodiversity, pursuing climate-resilient water resource management, promoting a sustainable and climate-resilient Blue Economy, and nurturing a circular economy. These priorities were reflected in many initiatives as well as the New Delhi G20 Declaration.

A notable project was the India-led and chaired Global Biofuels Alliance, contributing to the global quest for cleaner and greener energy. Recognising biofuels’ role in decarbonising transport, India set an example by achieving 10-percent ethanol blending ahead of schedule. It is on-track to reach a 20-percent blending target by 2025.[57] Brazil is also aiming for increased biodiesel blending, from 10 percent in 2022 to 15 percent by 2026.[58] The role of the Biofuels Alliance becomes crucial as these countries progress towards their targets.

A second crucial initiative is the launch of the Resource Efficiency and Circular Economy Industry Coalition (RECEIC), aiming to enhance access to necessary finance through alliances, technological cooperation, knowledge transfer, and innovation.[59] LMICs, already grappling with climate change and biodiversity loss, require support to transition to a circular economic model,[60] promoting the shared, reused, and recycled use of resources under sustainable production and consumption frameworks. The RECEIC could serve as a good policy continuity as Brazil takes over the helm of the G20. A commendable addition is the establishment of the Green Hydrogen Innovation Centre, led by the International Solar Alliance; it is designed as a knowledge-exchange centre to ensure that actionable ideas are developed to meet global decarbonisation goals through Green Hydrogen.

In line with the Indonesian proposal for a G20 Partnership for Ocean-based Actions for Climate Mitigation and Adaptation, India spearheaded the Ocean 20 Dialogue and presented an inception report for a study on accelerating the transition to a sustainable and climate-resilient Blue Economy, covering all G20 countries. This initiative by the Indian Presidency was acknowledged by G20 leaders during the final Ministerial meeting.[61]

Simultaneously, a dedicated G20 ETWG in India addressed technology gaps, low-cost financing, energy security, and diversified supply chains for energy transitions. India reaffirmed its commitment to emissions reduction and increased use of non-fossil fuel-based energy resources, targeting a 45-percent reduction in emissions intensity of GDP by 2030 from 2005 levels and close to 50 percent cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based sources.[62]

Climate finance and reform have been central themes for the G20 Presidencies of Indonesia and India. Despite Indonesia’s inability to secure new financial pledges for the US$100-billion annual climate finance goal announced at COP26, India has persistently advocated for fair global carbon budget allocations on behalf of itself and other developing nations, guided by the principle of ‘Common but Differentiated Responsibilities’. The Indian Presidency secured key commitments: G20 leaders broadly vowed to ensure access to multilateral climate funds and enhance their capacity to mobilise private capital. The Leaders’ Declaration[63] explicitly acknowledged the imperative for increased global investments to fulfil the climate goals of the Paris Agreement, emphasising the need to escalate investment and climate finance “from billions to trillions of dollars globally from all sources.” The Declaration reaffirmed the 2010 commitment by developed economies to jointly mobilise US$100 billion in climate finance per year by 2020 and annually through 2025 to support the necessary mitigation measures in developing countries. Additionally, a direct call was made to establish a measurable, transparent New Collective Quantified Goal for climate finance in 2024, starting at a baseline of US$100 billion per year.

Both Indonesia and India recognised the pivotal role of climate adaptation and mitigation in agriculture, aligning with the Paris Agreement.

Under Indonesia’s Presidency, enhancing global food security while considering climate change and environmental goals took centrestage. The Agriculture Working Group (AWG) directed its efforts towards three key areas: developing resilient and sustainable agriculture; promoting transparent and non-discriminatory agricultural trade; and fostering digital ‘agri-preneurship’. Upon assuming the G20 presidency, India confronted escalating food insecurity, particularly in developing and least-developed countries, accompanied by a rise in malnutrition. India’s AWG underscored four pivotal domains: food security and nutrition; sustainable agriculture with a climate-smart approach; inclusive agri-value chains and food systems; and digitalisation for agricultural transformation.

Under Indonesia’s leadership, member nations collaborated to enhance the Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS) that provides accurate market data on agricultural commodities. They pledged to increase participation, enhance data quality and timeliness, and develop user-friendly tools. During India’s G20 Presidency, there was a renewed emphasis on strengthening AMIS and Group on Earth Observations Global Agricultural Monitoring (GEOGLAM).[e] India, in its Declaration, committed to strengthening the GEOGLAM and AMIS—aimed at increasing market transparency, reducing price volatility, and improving food security coordination at national, regional, and global levels.

The significance of research collaboration for cultivating resilient and nutritious grains like millet, quinoa, and sorghum gained prominence during India’s Presidency. G20 member states endorsed initiatives such as the G20 Millet and Ancient Cereal System (MACS) to bolster research on ancient grains.[f]

Indonesia and India urged for collaborative action from organisations such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), World Bank, and World Trade Organization (WTO) to map global food insecurity. During India’s Presidency, the G20 Agriculture Ministers ratified the Deccan High-Level Principles on Food Security and Nutrition 2023, signalling a collective commitment to combat global hunger and malnutrition. A pledge was made to replenish resources for the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) to support crucial global efforts in the fight against food insecurity.

Both Presidencies aimed to champion fair and rules-based trade in agriculture, food, and fertilisers while minimising market distortions. These efforts, consistent with sustainable practices and WTO requirements, sought to enhance environmental and economic outcomes.

In Indonesia, G20 nations affirmed the transformative potential of research, innovation, and digital technology in agriculture to enhance sustainable food production, marketing, and storage while elevating farmer livelihoods and their market access, and ensuring robust data security. Under India’s Presidency, emphasis was placed on building inclusive digital infrastructures to drive socio-economic changes in agriculture. The strategy focused on farmer-centric digital innovations, including broadband internet access, data rights, and privacy protection. Recognising collaboration, international cooperation, and targeted investments as essential, the goal was to facilitate innovation and entrepreneurship, ensuring that underrepresented groups throughout the agri-food value chain have access to affordable solutions.

Digital public goods are pivotal for advancing the global development agenda across domains that include finance, public health, and agriculture. During its G20 Presidency, Indonesia took a proactive stance in this area and established the Digital Economy Working Group (DEWG). The group aimed to address post-COVID-19 issues of digital connectivity, digital literacy, responsible data flow, cybersecurity, data privacy, online safety, and the ethical use of artificial intelligence. Aligned with Indonesia’s vision and the broader South-South collaboration framework, India’s DEWG prioritised DPI for inclusive innovation, ensuring safety, security, resilience, and trust in the digital economy, alongside fostering a future-ready global workforce through digital skilling.

Under the Indonesian Presidency, notable achievements included the creation of knowledge resources empowering vulnerable populations to engage in the digital economy. A G20 Toolkit for Measuring Digital Skills and Digital Literacy was devised. India furthered these efforts by championing the digital skilling of a forward-looking, empowered workforce. The G20 Roadmap to Facilitate Cross-Country Comparison of Digital Skills—outlining steps for a shared understanding of digital competencies, and credentials across member states and beyond—garnered full endorsement. The New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration explicitly committed to halving the digital gender gap by 2030. India additionally proposed establishing a virtual Centre of Excellence (CoE) to foster the exchange of best practices, learnings on digital skilling initiatives, and professional certifications among interested nations.

Under Indonesia’s leadership, the G20 Digital Innovation Network (DIN) was established to facilitate dialogues between industry stakeholders and member states, to negotiate commercially viable agreements. The DIN, along with its complementary G20 DIN Whitebook, showcased innovative solutions from startups, providing networking opportunities and valuable market insights. Another manifestation of Indonesia’s leadership is the Yogyakarta Financial Inclusion Framework—an implementation guide for digital financial inclusion for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) and a data harmonisation framework. Among other aims, it seeks to support regulatory authorities in responsible digitalisation and promoting the economic potential of women and youth.

During India’s Presidency, the G20 focused on the role of DPI in advancing financial inclusivity, scalability, interoperability, effective Big Tech regulation, and risk management. Member nations stressed the importance of sharing domestic insights on DPI development and deployment, extending beyond the G20. To this end, the DEWG introduced the G20 Framework for Systems of Digital Public Infrastructure—an optional, collective guide for establishing, implementing, and governing DPI. Complementing this, India has started building the Global Digital Public Infrastructure Repository (GDPIR), a virtual collection featuring voluntarily shared DPI solutions from G20 member states and beyond. The G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration also welcomed the One Future Alliance (OFA) proposed by India, aimed at enhancing capacity, providing technical assistance, and offering funding for the DPI implementation in LMICs.

Amid the escalating importance of digital interventions in healthcare, particularly in low-resource settings and in response to events like COVID-19, initiatives in surveillance, testing, and contact tracing are becoming vital and complex. India’s Co-WIN, globally recognised as a digital solution, played a pivotal role in the world's largest vaccination drive.[64] The impact of digital platforms on the GDP of developing countries is evident,[65] with multilateral organisations emphasising the enhancement of digital ecosystems in these economies.[66] In this context, initiatives like GDPIR and WHO’s GIDH emerge as significant contributors to shaping the discourse on digitally connected nations and the future of digital health ecosystems in the Global South. They facilitate an exchange of best practices, success stories and concerns, further underlining the significance of the Global South countries holding consecutive Presidencies.

During the Indonesian and Indian Presidencies, significant developments unfolded across key global issues in economics, gender equity, and women's empowerment.

Indonesia focused on bolstering the International Financial Architecture by monitoring capital flows, ensuring global financial stability, and supporting the International Monetary Fund’s Integrated Policy Framework. It underscored infrastructure investment as a pivotal element for sustainable economic recovery. Under Indonesia’s Presidency, the G20 endorsed frameworks for private sector involvement in sustainable infrastructure and deliberated on quality infrastructure indicators. Furthermore, G20 members reaffirmed their commitment to international tax agreements (Pillar One and Pillar Two) to counter base erosion and profit shifting, with an emphasis on addressing the tax agendas of developing countries. Lastly, the G20 urged MDBs to amplify development financing, aiming to strengthen global financial safety nets and support the ongoing global economic recovery.

During the Indian Presidency, the establishment of an Expert Group aimed at strengthening MDBs was a notable initiative. In anticipation of the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting, the two-volume report, “Strengthening Multilateral Development Banks: The Triple Agenda Report of the Independent Experts Group,”[67],[68] was released. It recognised the critical emphasis on the triple mandate of global public goods provision, poverty reduction, and inclusive growth. It underscored the imperative to triple MDB funding by 2030 and advocated for the creation of an alternative financing window to attract diverse donors, including sovereign wealth funds and philanthropies.

On gender equity, Indonesia, in coordination with the G20 EMPOWER Group, acknowledged[69] the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on women and girls. A commitment was made to prioritise gender equality and women's empowerment in recovery and development initiatives. This entails promoting equal access to education, eradicating gender-based violence, improving access to finance and digital technology, addressing workforce imbalances, closing the gender wage gap, and enhancing the overall quality of life for women. Indonesia further collaborated with G20 EMPOWER to consolidate best practices and insights from women leaders, resulting in a knowledge-sharing playbook,[70] “Action in Progress: Advancing Women Towards Leadership”.

India’s W20 prioritised women-led development for enhanced equality and equity across policy domains. A commitment was made to establish a dedicated working group, commencing with Brazil’s upcoming G20 Presidency, to promote both women’s development and women-led development. Additional focus areas included women in entrepreneurship, grassroots women’s leadership, education, skill development, and positioning women and girls as change-makers in climate resilience. Specific recommendations in the W20 Communiqué 2023[71] included offering a minimum 15-percent tax break or equivalent incentives for women-led technology and tech-enabled start-ups. Proposed actions also involved publishing an annual G20 Digital Gender Equality Report, advocating for Gender-Responsive Public Procurement programmes, and ensuring customised national targets for procurement from women-owned and -led MSMEs. A commitment was made towards gender-responsive and environmentally resilient solutions in areas like water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), as well as inclusive agricultural value chains led by women farmers.

The New Delhi G20 Leaders’ Summit Declaration strongly endorsed economic and social empowerment, bridging the gender digital divide, gender-inclusive climate action, and securing women’s food security, nutrition, and well-being. These commitments establish the groundwork for progressive initiatives during the upcoming G20 Presidencies of Brazil and South Africa, ensuring sustained efforts toward economic recovery and gender equity.

The collaborative efforts of Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa played a pivotal role in ensuring that the G20 Leaders’ Summit in New Delhi concluded with a Declaration. Contrary to claims suggesting a compromise by Global North on wording around the conflict in Ukraine, the success of the Summit can be attributed to skilful Indian negotiations and the joint proposal presented by Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa, just hours before the summit.[72] The proposal, unchanged in its eight paragraphs, formed the basis of the Summit Declaration, focusing on the theme, ‘For the Planet, People, Peace and Prosperity’.

India concluded its G20 Presidency by welcoming the African Union as a permanent member, and shortly before the UN’s mid-term review of progress towards the SDGs was initiated. As a sobering reality emerges on the stalled progress on the SDGs, Indonesia and India have set the groundwork for potential course-correction by leveraging the G20. The Global South is ideally placed to maximise gains with the G20 handover to Brazil in 2023-24, and to South Africa the following year.

India has emphasised the need to give greater voice to the Global South through its ‘Voice of Global South Summit 2023’. The summit aimed to foster a more just worldview, addressing priorities, perspectives, and concerns of emerging economies. Discussions covered geopolitical fragmentation, shortages due to the Ukraine conflict, terrorism, human-centred globalisation, balancing climate goals and development, and resilient renewable energy access. The outcomes mirrored the agendas that Brazil and South Africa are likely to take forward, indicating continuity for the benefit of the Global South.

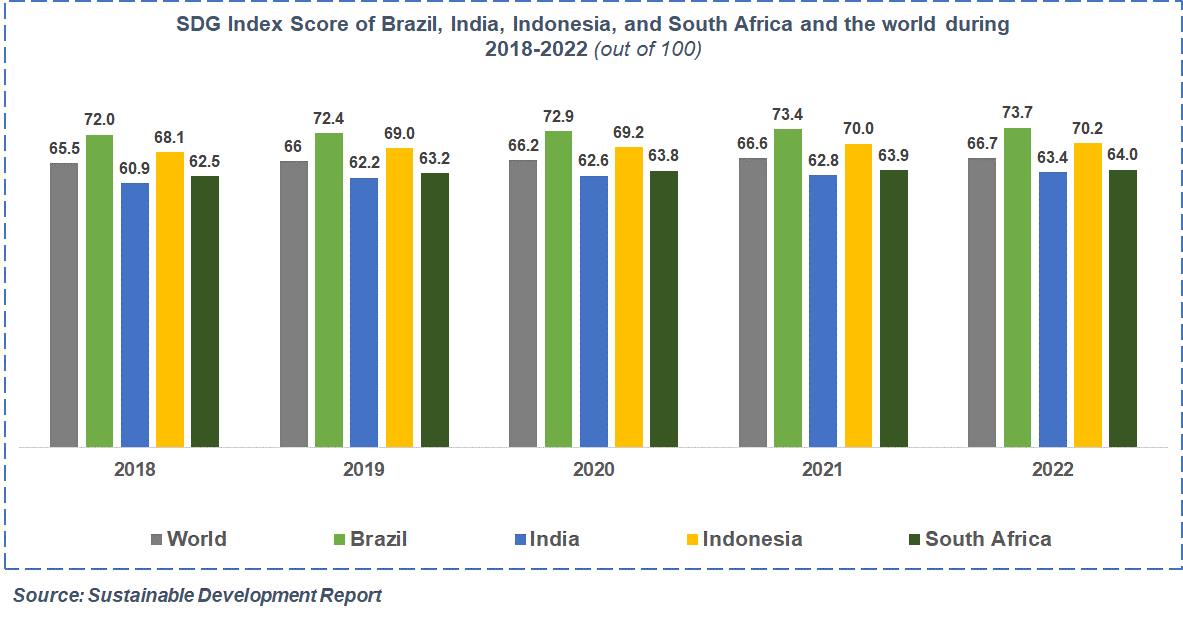

The 2023 Sustainability Development Report reveals Brazil’s notable achievements in SDGs 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 11, 13, and 17; progress has slowed for other goals. With an overall SDG score of 73.7, Brazil ranks 50th among 166 countries, poised to influence Global South perspectives during its upcoming G20 Presidency. South Africa lags behind Brazil, holding the 110th position with a score of 64. While showing moderate improvement in certain SDGs, it faces challenges in meeting the overall goals and falls short of the desired progress rate.

Recent speeches and past interventions made by the Presidents of Brazil and South Africa at various convenings, interviews with domain experts, and a literature review of policy papers and press reports, are indicative of the focus areas that the two forthcoming G20 Presidencies are well-positioned and likely to undertake.

Fig. 5: SDG Index Scores of Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa, vs. Global Averages

Note: The scores are out of 100

Source: Sustainable Development Report, SDSN[73]

Both Brazil and South Africa encounter hurdles in attaining SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being). Following the COVID-19 health crisis, Brazil’s healthcare sector rebounded in 2021.[74] However, the country continues to grapple with issues such as high maternal mortality rates, inadequate vaccines for infants, incidence of tuberculosis, and new HIV infections.[75] Similarly, South Africa actively addresses maternal mortality rates and the provision of infant vaccines. Although strides have been made in reducing tuberculosis and new HIV infections, persistent challenges afflict the country’s vulnerable populations. Emphasising comprehensive and universal healthcare is paramount, underscored by South Africa’s commitment to a National Health Insurance scheme,[76] making UHC relevant for their G20 Presidencies.

Brazil and South Africa, during their respective G20 Presidencies, have the opportunity to enhance the emphasis on the One Health approach. Building upon India’s suggestions, they can drive collaboration between Finance and Health ministries to ensure vital funding for pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response (PPR). Additionally, by exploring the formation of task-specific regional consortiums, like the Partnerships for African Vaccine Manufacturing launched in 2021, they can efficiently address shortages and facilitate a coordinated response to future outbreaks.

South Africa’s proposal at a meeting of the Africa Centre for Disease Control on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly[77] provides valuable direction for its G20 Presidency. The proposal centres on outlining mechanisms for regional engagement with the global community in future pandemics. Specifically, South Africa has been advocating for Africa’s vaccine independence through the creation of a regional legal instrument tailored for the continent. This instrument would serve as a cooperative mandate for PPR, activated in response to a declaration of a public health emergency with continental security or international implications.

While acknowledging the success of the WHO’s Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), which raised US$24 billion, distributed 1.96 billion vaccine doses, and procured over US$700 million worth of protective gear for health workers,[78] South Africa has previously highlighted the need to rectify ACT-A’s gaps and base it on principles of accountability and fair governance, ensuring a partnership of equals. Its forthcoming G20 Presidency is anticipated to serve as a platform for seeding this recalibration.

Brazil, for its part, could leverage its formidable generic drugs industry and advocate for bolstering accessibility to medicines globally. The country can spearhead initiatives to strengthen manufacturing and supply chains, building on discussions initiated by Indonesia and continued by India during their respective G20 Presidencies. Simultaneously, South Africa, armed with the African continent’s robust pharmaceutical manufacturing strategy crafted to address drug procurement and distribution gaps during the COVID-19 pandemic, can drive conversations within the G20. These discussions aim to enhance local and regional manufacturing capabilities for medical supplies, ensuring self-sufficiency in times of crisis. The upcoming G20 Presidencies also present a crucial opportunity to respond to the growing demand for collaborative frameworks at both national and international levels.

As one of the world's fastest growing economies, Brazil possesses unparalleled biodiversity and abundant resources. However, it confronts the urgent challenge of preserving the Amazon rainforest amid the climate crisis, and obstacles such as rising electricity tariffs and elevated prices for liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). Nevertheless, it has achieved notable success in establishing an exceptionally green energy matrix, with nearly 87 percent of Brazil's electrical power derived from clean and renewable sources.[79]

South Africa faces pressing challenges in achieving SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), marked by a declining electricity access rate and a near-stagnant share of renewable energy in the total energy mix. A common obstacle shared with India lies in the financial instability of state-owned power entities that dominate the energy sector. This constrains investments essential for expanding the national transmission grid and hinders the seamless integration of new renewable sources. Further, the spectre of climate change casts a threat over South Africa’s coastal regions, infrastructures, and ecosystems.

Upon receiving the G20 gavel from India’s G20 Presidency in early September, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva outlined Brazil’s clear focus: energy transition and sustainable development, aimed at fostering a fair world. This echoes the priorities set by India in 2023 and Indonesia in 2022. South Africa, under President Cyril Ramaphosa, is also likely to urge the G20 to intensify efforts against climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss, while recognising diverse development pathways for emerging economies.

Endowed with abundant solar, wind, and mineral resources, South Africa can strategically position itself as a global leader in renewable energy, green hydrogen, and sustainable industrialisation. Being emerging economies with varied energy scenarios, Brazil and South Africa are positioned to leverage their G20 Presidencies to demonstrate the advantages of renewable energy and climate financing in promoting sustainable growth and energy reliability.

Both countries can jointly advocate for heightened investment in sustainable development projects. President Lula’s proposal for a G20 Task Force for Global Mobilization against Climate Change offers a strategic direction for this, as does President Ramaphosa’s recent appeal[80] for reforming the mandates of MDBs to align with the development priorities and climate commitments of emerging economies. The two can inspire collaborative discussions on implementing large-scale renewable energy projects, technology transfer, and capacity building within the G20. South Africa can amplify the appeal from African leaders[81] to the international community to assist in the continent’s efforts to increase renewable energy capacity by 2030. This includes investments in digital green technologies to decarbonise the transport, industrial, and electricity sectors.

Notably, leaders of both countries have repeatedly stressed the urgency of fulfilling climate finance commitments, particularly towards Global South countries bearing the cost of the industrialisation and development of the Global North. President Lula has emphasised the need for new climate and biodiversity finance, in addition to development finance,[82] while President Ramaphosa has called for Global North economies to meet their commitment of mobilising US$100 billion annually to tackle climate change[83]—“for a demand that has already reached trillion,” as President Lula outlined before the UN General Assembly in September 2023.[84] At the same gathering, President Ramaphosa stressed the need to operationalise the Loss and Damage Fund for vulnerable countries hit hard by climate disasters.[85] This was agreed to at COP27.[86]

Therefore, it is expected that Brazil and South Africa will use their G20 Presidencies to insist that climate financing is need-based, sufficient, transparent, equitable, accessible—and most importantly, fulfilled—for countries striving to meet their climate goals. They should also push the broader ambition of achieving a carbon-neutral global energy system by 2050 while minimising pollution of water, soil, and air.[87]

Brazil has placed the fight against hunger at the forefront of its G20 agenda. This commitment includes the establishment of the Global Alliance Against Hunger and Poverty, particularly significant as the indicator for SDG 2 (Zero Hunger).[g] The global hunger index reveals substantial regression in undernourishment levels, the prevalence of stunting in children, and a reduction in cereal yield in the country.[88] These challenges can be attributed to structural, racial, and gender inequalities, exacerbated by deteriorating conditions of food and water security.[89]

At the same time, Brazil has pioneered modern tropical agriculture techniques through strategic investments and technology integration, providing a valuable model for replication across G20 nations. President Silva’s proposal[90] to extend these techniques to the African Savannah underscores Brazil’s commitment to collaboratively addressing global hunger challenges. Brazil’s initiatives, such as the Zero Hunger plan,[91] demonstrate a multifaceted approach to reducing poverty and food insecurity. Notably, the Bolsa Família (Family Stipend) programme[92] has gained global recognition for its success in transferring income to families who ensure their children are vaccinated and attend school. In 2023, Brazil reinstated public policies that support family farming, which were shut down in 2019.

South Africa faces similar food security challenges as Brazil, except for an increasing annual cereal yield. In 2021, over 6.8 million households in the country reported experiencing hunger.[93] Rising food prices have become a massive concern. At the 2022 Bali Summit, South Africa emphasised the need for financial assistance and investment in climate-smart agriculture and sustainable food production systems for LMICs. It also called for the implementation of a rule-based, transparent, and predictable multilateral trading system.[94]

The imperative is reforming global food and agriculture policies and programmes, which requires cooperation between the Global North and Global South. Brazil and South Africa could exert pressure on other nations to support emerging economies in addressing their food security challenges. Such collaborations will enable emerging economies to partner with the Global North in achieving the global goal of ending world hunger by 2030. If the global community fails to address this, President Silva said at the G20 Leaders’ Summit in New Delhi, “we will face the biggest multilateral failure in recent years.”[95]

During India’s G20 Presidency, member nations pledged to exchange good practices for establishing an inclusive, open, fair, non-discriminatory, and secure digital economy within applicable legal frameworks for countries and stakeholders. Building on this commitment, Brazil and South Africa could utilise their G20 Presidencies to convene a multi-country, cross-sectoral group for knowledge-sharing, and foster collaboration to create digital safeguards.

DPI and Digital Financial Inclusion (DFI) have been important and cross-cutting topics of discussion across sectors, particularly during India’s Presidency in 2023. Brazil and South Africa can contribute to advancing the Global South’s agenda by adopting and promoting policies that nurture a robust DPI. This involves enhancing accessibility to financial services and engaging in multilateral initiatives to bridge the digital divide and foster inclusive digital financial ecosystems that will have a cross-cutting impact on all their priority areas.

Gender equity and economic recovery are interlinked aspects across the SDGs and hold relevance for the G20, as a global economic and social cooperation forum. Tackling gender inequities not only fosters rapid economic growth but also improves social, and health outcomes, aligning with the broader 2030 Development Agenda.[96] The emphasis on gender equity and women’s economic empowerment during India’s and Indonesia’s G20 Presidencies signals a recognition of gender equity as a worthy global and human goal but also a catalyst for economic recovery. Brazil and South Africa in their upcoming Presidencies are likely to pursue the two earnestly.

At the G20 Leaders’ Summit in New Delhi, Brazil’s President Silva emphasised the importance of placing the reduction of gender inequality at the centre of the international development agenda.[97] Brazil has taken concrete steps by passing a bill that mandates equal pay for equal work for men and women.[98] At the UN General Assembly in September 2023, President Silva pledged to fight femicide and all forms of violence against women,[99] while South Africa’s President Ramaphosa highlighted the imperative of eliminating gender discrimination by ensuring equal access to healthcare, education, and economic opportunities for women.[100]

South Africa is expected to leverage its G20 Presidency to mobilise member nations and advance policies for improved health access and outcomes for women. These include improved global financing mechanisms and investments to meet the health and well-being needs of women, children, and adolescents.

Despite facing economic challenges, Brazil and South Africa have the potential to foster a more equitable and sustainable global economy. Brazil is grappling with slower economic activity driven by weakened private consumption and subdued exports.[101] Increased social transfers aim to boost household consumption, but their impact has been constrained by high inflation and a stagnant credit flow. South Africa, Brazil’s successor in the G20 Presidency, faces a comparable macroeconomic outlook with high inflation and interest rates.[102] Fiscal efforts to stimulate the economy are encountering challenges due to the ongoing global energy crisis. Yet, the consensus is that the next decade belongs to Africa—the continent is poised to drive global economic growth in the coming decades as other major economies like China slow down.[103] Africa, including South Africa, with their demographic advantage of a young and growing population, has the potential to power the world through its labour force and consumer markets.

During its G20 Presidency, Brazil is expected to advocate for international financial systems that help Global South countries implement structural changes to their economies and make them more equitable and sustainable. At the BRICS Summit in August 2023, President Silva called for adequate representation of Global South countries in Bretton Woods institutions and their climate funds to achieve this goal.[104] Similarly, South Africa is anticipated to leverage its G20 Presidency to strengthen and reform the international financial architecture, making it resilient to climate shocks. In his public statements, President Ramaphosa has repeatedly stressed the importance of reframing the mandates of MDBs to respond to the needs of developing economies,[105] designing systemic interventions for debt management and relief,[106] and leveraging the balance sheets to scale up concessional finance.[107]

Finally, both upcoming G20 Presidencies are in an ideal position to push for more and new Global South-first public financing to support climate adaptation and build resilience, thus also aiding global economic recovery.

While endorsing the UN and the Secretary-General’s initiatives to address funding shortfalls for achieving the SDGs, this report provides additional recommendations for G20 stakeholders. These recommendations have been formulated and sourced through extensive interviews with experts in international relations, global macroeconomics, energy security, climate change, digital economy, food security, and gender. They are in no particular order of importance but have been stacked against relevant thematic areas that have an outsized impact on achieving the SDGs. The experts, while delving into these, have taken into consideration the social and cultural contexts of the emerging economies and the Global South.

G20 nations could establish aligned policies to promote the adoption of DRE systems, creating an environment conducive to DRE investments. Efforts should focus on boosting technical and institutional capabilities for DRE deployment, including training, knowledge-sharing, and collaborative initiatives across public, private, and educational sectors.

Addressing financing challenges through innovative financial instruments like green bonds, impact investing and public-private partnerships, is crucial for the widespread adoption of DRE.[109]

A roaring consensus on gender equity and women-led development across G20 Presidencies must be built on as the mantle is taken forward. India’s suggestion of the formation of a women’s empowerment working group will become operational during Brazil’s presidency.

There is a unique chance for this working group to be intersectional and collaborative with other working groups and Ministers. A strong gender-equitable lens foregrounding core initiatives is key. At the same time, G20 forums should lead by example to ensure the representation of women and gender minorities across discussions and negotiations.

Past and future G20 Presidencies have stressed the need for key reform in MDBs. The need for a substantial increase in MDBs’ sustainable lending is underscored by global challenges. Enhancing private sector participation can bring additional resources and expertise. Increased inter-MDB cooperation is essential to crafting a unified response to global challenges, particularly those related to sustainable development and climate change. A regular assessment of priorities and performance by the global community is proposed to guide the agendas of MDB governing bodies. The present shareholding structure in MDBs mirrors economic and political history, resulting in high-income nations holding disproportionate voting power. This warrants a reform to usher in a fair voting system.

The recommendations in this report span varied critical sectors but at their core lies a continuity of influence, priorities, and shared vision. The G20 has clearly and powerfully demonstrated its ability to address global challenges across sustainable development, climate change, MDB reform, as well as the critical themes of privacy, protection, and regulation in the expanding realm of DPI. Regular meetings between the four G20 Presidencies of Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa as an informal grouping can sustain and amplify these discussions ensuring continuity and resonance, within and outside the G20. The collective actions of G20 economies have reinstated confidence that pivotal economies of the Global South, with their distinctive voices, can shape better global outcomes in a shifting world order.

This report has been jointly prepared by Global Health Strategies (GHS) and Observer Research Foundation (ORF).

GHS and ORF thank all those who generously contributed their time and expertise throughout the course of this report's development. Their insights played a valuable role in shaping both the quality and depth of this report. We extend our special appreciation and gratitude to Ambassador Pinak Ranjan Chakravarty, Former Secretary (Economic Relations) at the Ministry of External Affairs, India, and Co-founder of Deep Strat; and Professor Rajat Khosla, Director of the United Nations University International Institute for Global Health (UNU-IIGH) for their overall guidance and critical perspectives on various aspects of the report.

[a] The events surrounding the recent attack by Hamas on Israel and the subsequent retaliation on Gaza are noteworthy but have not been factored into this report. This conflict has the potential to impact geopolitics and economic recovery—the complexities and ramifications of which are beyond the scope of the current analysis.

[b] As per the WHO, One Health is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimise the health of people, animals and ecosystems. It recognises that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are linked and interdependent.

[c] WHO’s Global Digital Health Strategy 2020-2025 was endorsed by the seventy-third World Health Assembly in decision WHA73(28) (2020). The strategy sets out a vision, the strategic objectives and a framework for action and implementation to advance digital health, globally and within countries at national and subnational levels.

[d] The funding for the operation of the GIDH secretariat is expected to be derived from the funds allocated to support the Department of Digital Health and Innovations at WHO, including assessed contributions (if available), philanthropic support, and voluntary contributions.

[e] Group on Earth Observations Global Agricultural Monitoring Initiative (GEOGLAM) increases market transparency and improves food security by producing and disseminating relevant, timely, and actionable information on agricultural conditions and outlooks of production at national, regional, and global scales. It achieves this by strengthening the international community’s capacity to utilise coordinated, comprehensive, and sustained Earth observations.

[f] India’s expertise in millet production has been globally recognised, especially during the United Nations’ International Year of Millet, further highlighting the value of diverse food consumption, biofortification, food and cash-based nutrition safety net programmes, and sustainable agriculture for achieving the SDGs.

[g] Goal 2 aims to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture by 2030.

[h] The G7 Climate Hub is built around advancing climate change mitigation policies towards climate neutrality; transforming industries to accelerate decarbonisation; and boosting international ambition through partnerships and cooperation to facilitate climate action and promote just energy transition.

[i] Global Climate Alliance (GCA) Collaborative is an independent research effort to evaluate how the Global South can best ally with the Global North to accelerate climate action. The goal is to facilitate mutually-beneficial decarbonisation pathways between countries, through necessary financial and technology partnerships.

[1] Inge Kaul, ed., Providing Global Public Goods (Oxford Academic), February 13, 2003.

[2] Lakshmi Puri, “African Union and the G20: Africa on the High Table,” The Indian Express, September 13, 2023.

[3] Firstpost, “G20 Troika First Time with Developing World, Can Amplify Voice of Global South: PM Modi,” September 6, 2023.

[4] United Nations, “Warning Over Half of World Is Being Left Behind, Secretary-General Urges Greater Action to End Extreme Poverty, at Sustainable Development Goals Progress Report Launch,” UN Press, April 25, 2023.

[5] World Health Organization, “Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic,” May 5, 2023.

[6] UN Women, “Ukraine and the Food and Fuel Crisis: 4 Things to Know,” September 22, 2022, https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/feature-story/2022/09/ukraine-and-the-food-and-fuel-crisis-4-things-to-know.

[7] World Economic Forum, “The Global Risks Report 2023, 18th Edition,” January 2023, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf.

[8] Stephen Johns and Dr Sabine L. van Elsland, “Coronavirus will have bigger impact on world’s most disadvantaged and vulnerable,” Imperial News, May 13, 2020, https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/197498/coronavirus-will-have-bigger-impact-worlds.

[9] Akihiko Nishio, “COVID-19 Is Hitting Poor Countries the Hardest. Here’s How World Bank’s IDA Is Stepping up Support,” World Bank Blogs, October 2, 2023, https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/covid-19-hitting-poor-countries-hardest-heres-how-world-banks-ida-stepping-support.

[10] Nicolò Gozzi et al., “Estimating the Impact of COVID-19 Vaccine Inequities: A Modeling Study,” Nature Communications, June 6, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39098-w.

[11] World Health Organisation, “Invisible Numbers: The True Extent of Noncommunicable Diseases and What to Do About Them,” World Health Organisation 2022, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240057661.

[12] World Health Organisation, “Noncommunicable Diseases,” September 16, 2023, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

[13] NCD Alliance, Invest To Protect: Financing as the Foundation for Healthy Societies and Economies, NCD Alliance 2022, https://Ncdalliance.Org/Sites/Default/Files/Resource_files/NCD%20Financing_ENG.Pdf.

[14] World Health Organisation, Probability of dying between the exact ages 30 and 70 years from cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, or chronic respiratory diseases (SDG 3.4.1), World Health Organisation 2021,

[15] National Ocean Service, “What are El Niño and El Niña?,” https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ninonina.html.

[16] Jagdish Krishnaswamy, “From Western Disturbances to El Niño, Climate Change Is Affecting India’s Food Security,” The Hindu, September 12, 2023, https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment/summer-monsoon-impact-india-food-security/article67291707.ece.

[17] United Nations, Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals: Towards a Rescue Plan for People and Planet United Nations, 2023, https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/SDG_Progress_Report_Special_Edition_2023_ADVANCE_UNEDITED_VERSION.pdf

[18] Bineswaree Bolaky, “Leveraging South-South Cooperation to Finance the SDGs,” Observer Research Foundation Issue Brief No. 620, March 10, 2023, https://www.orfonline.org/research/leveraging-south-south-cooperation-to-finance-the-sdgs/.

[19] Jeffrey D Sachs, et al, Sustainable Development Report 2022, Cambridge University Press 2022. https://s3.amazonaws.com/sustainabledevelopment.report/2022/2022-sustainable-development-report.pdf.

[20] United Nations, System-wide Strategy on South-South and Triangular Cooperation for Sustainable Development, United Nations, 2021, https://www.unsouthsouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/United-Nations-system-wide-strategy-on-South-South-and-triangular-cooperation-for-sustainable-development-2020%E2%80%932024.pdf.

[21] Boussery Gunter, “Measles Cases Are Surging — and I’m Scared for Vulnerable Children.”. United Nations Children’s Fund. April 26, 2023. https://www.unicef.org/rosa/blog/measles-cases-are-surging-and-im-scared-vulnerable-children.

[22] World Health Organization. WHO issues urgent call for global climate action to create resilient and sustainable health systems, World Health Organization, May 24, 2023, https://www.who.int/news/item/24-05-2023-wha76-strategic-roundtable-on-health-and-climate.

[23] Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, “Goalkeepers Report 2023”, https://reliefweb.int/attachments/fe52be35-9ec4-4335-ba97-75943184a191/2023-goalkeepers-report_en.pdf.

[24] World Health Organization, Report on Digital Health Implementation Approach to Pandemic Management, 2020.

[25] Bhaskar Chakravorti, “60 Countries’ Digital Competitiveness, Indexed,” Harvard Business Review, September 20, 2017, https://hbr.org/2017/07/60-countries-digital-competitiveness-indexed.

[26] Roopa Dhatt, et al, “Women In Health Care,” Think Global Health, October 30, 2021, https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/women-health-care-call-pandemic-equity.

[27] World Health Organization, “Probability of dying between the exact ages 30 and 70 years from cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, or chronic respiratory diseases (SDG 3.4.1),” https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/probability-of-dying-between-exact-ages-30-and-70-from-any-of-cardiovascular-disease-cancer-diabetes-or-chronic-respiratory-(-)