-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Sunaina Kumar and Ambar Kumar Ghosh, “Elected Women Representatives in Local Rural Governments in India: Assessing the Impact and Challenges,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 425, January 2024, Observer Research Foundation.

The political representation of women is crucial to deepening democracy and advancing gender equality. This also has tangible political and economic gains. Research shows that having more women in politics leads to more effective policy outcomes, reduced corruption, and less conflict; women leaders tend to foster economic and developmental growth while promoting more inclusion of women in the labour force.[1] Indeed, according to the critical mass theory, the presence of a certain number of women, termed as a ‘considerable minority’, in governance structures is important to impact policy. The theory terms women representatives in politics as the ‘critical mass’ whose presence should not only ensure the descriptive representation of women in terms of their presence in the political and governance landscape but also result in substantive policy change for the empowerment of the female population.[2] Many countries, including India, have adopted gender quotas as a means to address historical imbalances and the cultural, social, and economic barriers linked with women’s political exclusion. Indeed, legislated gender quotas have proved to be effective at increasing women’s political representation; countries with such quotas have a higher representation of women in local governments (by 7 percentage points) than countries without the quotas.[3] As of January 2023, 88 countries have introduced legislated gender quotas for local elections.[4]

India’s 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act,[a] which came into effect in 1993, reserved one-third of electoral seats for women in local governance structures in rural areas, known as Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs).[b] Thirty years since its enactment, India, a diverse and multilayered federal polity, has over 1.45 million women in local decision-making roles.[5]

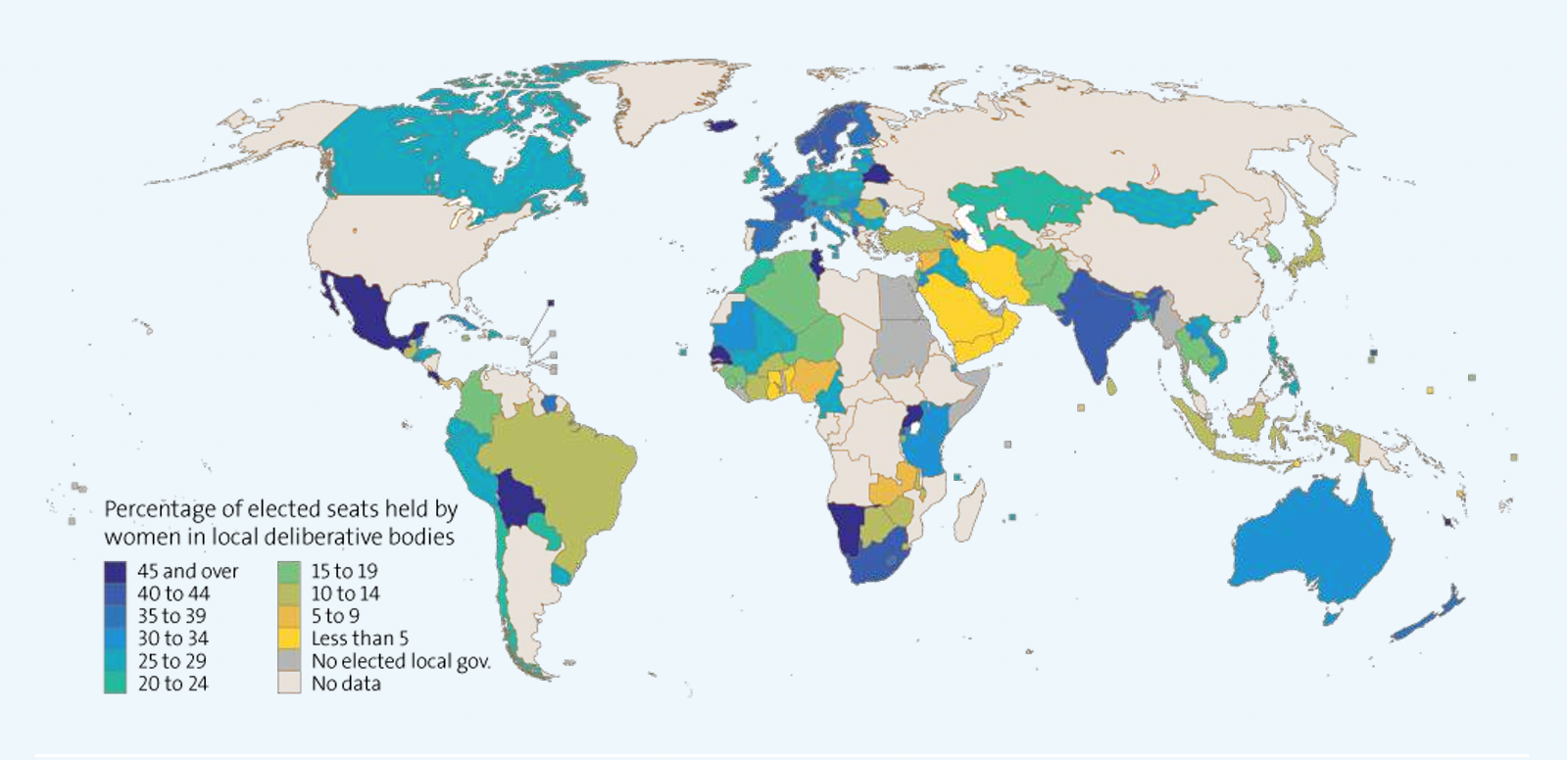

India climbed eight places in the 2023 Global Gender Gap report (ranking 127), which added the inclusion of women in local governance as a new indicator.[6] Only 18 of the 146 countries surveyed have achieved representation of women of over 40 percent in local governance. India is ranked among the countries with the highest participation of women in local governance (44.4 percent of all elected local government representatives are women), ahead of Global North countries like Germany (30.3 percent) and the UK (35.3 percent), and Global South contemporaries like Brazil (15.7 percent), Indonesia (15.7 percent), and China (28.1 percent).

The inclusion of a target on women’s political participation[c] in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework underlines the importance of women’s leadership at the local level in promoting and preserving democracy, and achieving the SDGs.

Figure 1: Women’s representation in elected local deliberative bodies (as of 1 January 2020)

Source: UN Women[7]

There is a growing recognition of the crucial link between local governance, development, and gender equality. Women play a critical role in emphasising local priorities, have an impact on developmental outcomes, and are essential in ensuring sustainable development in the spirit of decentralised governance. Research suggests that women political representatives have ensured better distribution of essential public goods than men, strengthening sustainable development at the grassroots in the true spirit of inclusive and decentralised democratic governance.[8] By bringing attention to inclusivity, prioritising policies that support families, and advocating for gender equality, women contribute to creating more equitable and responsive local communities.[9]

Until the 1990s, India accorded little priority to women’s political participation, even as the number of women voters increased steadily. The 73rd Constitutional Amendment sought to upend the prevalent traditional structures and entrenched systems of male-dominated political patronage in rural areas, empowering women to participate in political processes hitherto dominated by men. Gender-related indicators from when the amendment was introduced in the early 1990s point to the severe constraints women faced as they entered grassroots politics for the first time. The literacy rate of rural women in 1992-1993 was 34 percent compared to 65.9 percent in 2019-2021; the total fertility rate of rural women was 3.7 children per woman in 1992-1993, reducing to 2.1 in 2019-2021; the median age of marriage for women (in the 20-49 age group) has also improved, from 16.2 years in 1992-1993 to 19.2 years in 2019-2021.[10],[11] In the decades since the amendment, India has witnessed increased women’s representation in local governance. The impact can be felt in the improved delivery of public goods in villages with female leaders, and the weakening of stereotypes about women’s abilities to lead.[12]

However, there appears to be a “conspiracy of silence” around the good work of local governments in India.[13] This is even more conspicuous when the elected representatives are women. The contributions of elected women representatives (EWRs) are largely undervalued and neglected, with studies from several Indian villages showing that EWRs are likely to receive less favourable reactions even when their performance is better than that of male elected representatives.[14]

This paper attempts to review the role of women in local governance in rural India (at the panchayat level) over the years, delineate the achievements, and analyse persisting challenges. The paper also presents policy recommendations for enhancing women’s participation in local governance. The paper draws insights from secondary literature, including books, research articles, news reports, and survey reports in this domain. The authors have also interviewed women panchayat-level representatives, officials, and bureaucrats who have worked in PRIs, as well as representatives from civil society organisations engaged in capacity-building initiatives for EWRs.[d] These have been used as primary data to substantiate the paper’s findings. This study is only confined to women’s representation in local governance structures at the rural level. The state of women’s representation in urban bodies of local governance is beyond the scope of this paper.

India’s federal political system provides for three tiers of government—national, state, and local levels. Local-level institutions of self-governance fall under two categories: municipal bodies and town councils in the urban areas and PRIs in the rural areas. A sizeable majority (65 percent) of the total population in India resides in rural areas.[15] This makes the PRIs a crucial instrument of political representation that impacts everyday governance and welfare for considerable sections of the populace. The panchayat system comprises councils at the village level (gram panchayat), block level (panchayat samiti), and district level (zilla parishad), with responsibilities for managing local public resources. Members of these councils are elected by local residents. The size of the gram panchayat can vary significantly in terms of the number of people and villages it covers, a variation observed across different states. During elections, locals vote to select council members and, in most states, directly elect a pradhan (council chief). Typically, candidates for these positions are put forward by political parties, but they must be residents of the villages they seek to represent. The council relies on majority voting for decision-making, and the pradhan does not possess the authority to veto decisions made by the council.[16]

Although local village-level structures of self-rule have a long history, the idea of promoting local self-government, as enshrined in Article 40, was positioned within the non-enforceable Directive Principles of State Policy of the Indian Constitution without any explicit mention of women’s representation.[17] The Balwant Rai Mehta Committee (1957), appointed to examine the working of India’s community development programme to address issues of decentralisation, recommended that the 20-member panchayat samiti should co-opt or nominate two women with an "interest in work among women and children."[18] The Maharashtra Zilla Parishad and Panchayat Samiti Act of 1961 followed this suggestion, allowing for one or two women to be nominated to each of the three PRI bodies if no woman candidate was elected. In 1978, out of 320 women representatives on the panchayat samitis and zilla parishads in Maharashtra, only six were elected. This demonstrated that the provision for co-option or nomination had a limited impact in accommodating women leaders in the panchayat system.

The Committee for the Status of Women in India, in its report titled ‘Towards Equality’ (1974), strongly highlighted that the concerns and viewpoints of rural women had not received adequate consideration in the government's plans and development policies.[19] It also proposed the establishment of statutory women's panchayats at the local level but did not advocate for reservation. In 1978, the Committee on Panchayati Raj Institutions (also called Ashok Mehta Committee) recommended reserving two seats for women in each panchayat.[20] The National Perspective Plan for Women (1988) recommended that 30 percent of the executive-head positions from the village to the district levels should be reserved for women.[21] The same recommendation was put forth in the unsuccessful 64th Constitutional Amendment Bill of 1989.[22] Eventually, in 1993, Panchayati Raj was formally incorporated into the Constitution through the 73rd Constitutional Amendment (for panchayats at the village, block, and district levels) and the 74th Constitutional Amendment (for municipalities) Acts, with both providing for the reservation of one-third of elected seats for women.[23] According to the 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act, “Not less than one-third of the total number of seats reserved under clause (1) shall be reserved for women belonging to the Scheduled Castes or, as the case may be, the Scheduled Tribes.” It also provides that “Not less than one-third (including the number of seats reserved for women belonging to the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes) of the total number of seats to be filled by direct election in every Panchayat shall be reserved for women and such seats may be allotted by rotation to different constituencies in a Panchayat.”[24]

Before the 73rd Constitutional Amendment mandated the reservation of seats for women at the local level, certain states had already taken steps to implement women’s reservations in panchayats. After Maharashtra adopted the recommendations of the Balwant Rai Committee in 1961, Karnataka initiated (in 1985) a 25 percent reservation for women in the mandal praja parishads (local people’s council) along with an additional reservation for women from the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. Similarly, in 1986, Andhra Pradesh established a reservation of between 22 percent and 25 percent for gram panchayats, with the provision of co-opting two women in the panchayat samiti in addition to the elected women members.[25] However, it is the constitutional amendments that had a transformative impact, resulting in the eventual elevation of over 1.45 million women to leadership positions in India's local governance (see Table 1). Presently, 20 states—Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Punjab, Rajasthan, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Tripura, Uttarakhand, and West Bengal—have expanded the reservation for women in their PRIs to 50 percent.[26] In some states, like Karnataka, women have even surpassed this threshold, with more than 50 percent representation in PRIs, indicating that women are now succeeding in electoral wards that were not specifically reserved for them.[27]

Table 1: Percentage of Elected Women Representatives in Panchayats in Indian States

| States | Percentage | States | Percentage | ||

| 1 | Andhra Pradesh | 50 | 16 | Manipur | 50.69 |

| 2 | Arunachal Pradesh | 38.98 | 17 | Odisha | 52.68 |

| 3 | Assam | 54.6 | 18 | Punjab | 41.79 |

| 4 | Bihar | 52.2 | 19 | Rajasthan | 51.31 |

| 5 | Chhattisgarh | 54.78 | 20 | Sikkim | 50.3 |

| 6 | Goa | 36.72 | 21 | Tamil Nadu | 52.98 |

| 7 | Gujarat | 49.96 | 22 | Telangana | 50.34 |

| 8 | Haryana | 42.12 | 23 | Tripura | 45.23 |

| 9 | Himachal Pradesh | 50.12 | 24 | Uttar Pradesh | 33.34 |

| 10 | Jammu and Kashmir | 33.18 | 25 | Uttarakhand | 56.01 |

| 11 | Jharkhand | 51.57 | 26 | West Bengal | 51.42 |

| 12 | Karnataka | 50.05 | |||

| 13 | Kerala | 52.41 | |||

| 14 | Madhya Pradesh | 49.99 | |||

| 15 | Maharashtra | 53.47 |

Though the reservation of seats has augmented women’s participation, the stories of women’s leadership at the local level are nuanced, multilayered, and replete with challenges.

Given India’s widespread diversity, and varied sociocultural dynamics and developmental priorities, women representatives have faced distinctive challenges. In response, some states have seen the emergence of all-women panchayats, such as the ‘Manje Rai Panchayat’ at Indapur Tehsil and Ralegaon Shindhi in Ahmednagar district in Maharashtra, and the ‘Kultikri Gram Panchayat’ under the Jhargram subdivision in West Bengal. Factors such as the number of reserved seats for women in the panchayats, the level of participation of women in local politics, and the political party’s bid to mobilise support among women propelled the establishment of such all-women panchayats. These panchayats have performed well, with special emphasis on campaigns for increasing women’s literacy and initiatives to expand avenues of employment and entrepreneurship among local women in the villages. [29]

States like Karnataka, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, and Rajasthan have introduced mahila (women) gram sabhas to strengthen women’s participation. Due to a combination of social barriers and a lack of knowledge of rights and entitlements, women’s participation in gram sabha meetings across states has remained low.[30] A 2018 survey conducted by Participatory Research in Asia[f] in Rajasthan showed that most women had never attended a gram sabha meeting and had a low desire to get involved in local governance processes. The concept of mahila gram sabhas originated in Maharashtra when self-help groups (SHGs)[g] and female members of the community called a ‘mahila sabha’ (women’s meeting) against alcoholism. Since then, such gram sabhas have also focussed on women-centric issues like maternal health, domestic violence, female infanticide, child marriage, and livelihood opportunities for women.[31]

A 2008 study on EWRs by the Indian government’s Ministry of Panchayati Raj observed that in states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Assam, women pradhans were more likely to be engaged in household work, while it was least likely in states like Arunachal Pradesh and Kerala.[32] Incidentally, high engagement by women leaders in panchayat-related activities was noted in Kerala.[33] Another study revealed that while family members and community groups (such as SHGs, clubs, and mahila panchayats) motivate women leaders to contest elections, political parties are also extremely dominant in states like West Bengal, Sikkim, Tripura, and Kerala.[34] This is possibly because of the greater politicisation of rural life in these states.

Several states have also initiated various skills development programmes to enhance the leadership skills of women representatives in the panchayats. For instance, women’s empowerment training under the Kudumbashree initiative, a programme for SHGs in Kerala, facilitated women to develop efficient leadership skills in local-level politics in the last two decades.[35]

A 2004 study in Haryana found that “the major difficulties faced by female Sarpanches [panchayat head] to be the purdah [veil] system, hesitation or apprehension about ability to perform duties, lack of education, lack of awareness about the Panchayat system, and restrictions derived from physical mobility.”[36] The study also revealed some of the positive impacts on women’s empowerment by facilitating the “creation of political space for women, the opportunity to come out into the public and interact, the ability for women to share their problems with women leaders, and the construction of a new social status for women.”[37] Another study, based on interviews with 295 women sarpanches in 21 districts in Haryana, reveals that although EWRs face a slew of sociocultural hindrances, their willingness and ability to impact governance in panchayats has increased with time.[38]

A critical challenge to women’s representation is the placement of ‘rubber stamp candidates’ in reserved seats; a 2008 survey of three village panchayats in Punjab found that 75 percent of elected female representatives reported proxy participation by their husbands.[39] More recent studies confirm that the earlier challenges of having women as proxies have not entirely diminished in many states.[40] However, several studies have shown that women’s political agency and their involvement in panchayat work have significantly increased with time.[41],[42]

Despite being embedded in conservative societal environments, women leaders have emerged as instrumental drivers of social change in many villages across India. In Haryana, which is known for its low sex ratio, women panchayat-level leaders have made attempts to reduce the prevalence of the purdah system, encourage school education for girls, reduce open defecation, reduce school dropouts, and improve the sex ratio.[43] Women leaders in many other states have fought against the deeply entrenched conservative patriarchal structures and created conditions for women to be economically self-reliant with initiatives like forming SHGs for women.[44] There have also been instances of educated women giving up lucrative careers to contest panchayat elections in states like Rajasthan to contribute to developmental work in their villages.[45]

Additionally, the inadequate devolution of funds by state governments to PRIs has impacted gender-inclusive growth at the grassroots.[46] To counter this, some states, such as Kerala and Karnataka, have introduced gender budgeting in panchayats to mainstream gender concerns through the allocation of funds.[47]

Major Trends

Even though women leaders work under social and cultural constraints—the burden of caregiving, deep-rooted cultural biases, low levels of mobility, lack of role models in a field dominated by men, and lack of information and opportunities to develop negotiation skills—there has been a perceivable increase in their awareness, knowledge, and confidence levels, as decentralisation and devolution have slowly taken root in the country.

Certain key trends in the socioeconomic and demographic profile of EWRs are discernible, as are variations in the political careers of female and male representatives. These trends emerge from large-scale studies covering different states.[48] [49]

Impacts

The effectiveness of the work of EWRs can be analysed based on the impact on:

The reservation of seats for women paved the way for the greater political participation of women, while also demonstrating the efficient leadership and governance skills of women leaders in panchayat-level politics.[56] Women often differ from men in their policy preferences, and quotas for women have led to the more efficient utilisation of local resources in certain crucial spheres. A 2010 study across 11 states found that women-led villages saw improved delivery of services with lower levels of corruption. Greater investments were made in services like water infrastructure, sanitation, education, and roads, which were important to the community, especially women.[57],[58] The study also confirmed that female leaders receive a less favourable evaluation from citizens of the village, including its women. With greater access to education and more awareness of rights, the role of the new generation of EWRs has expanded as they work on welfare programmes by the government, which cover livelihoods and entitlements, sanitation, maternal and child health, nutrition and food security, education, childcare services, and social services.[59]

Women leaders have a positive impact on deliberative democracy and inclusive governance by improving participation in gram sabha meetings, which are organised at least twice a year to discuss local development issues. Studies show that female citizens are more likely to participate and speak in meetings where the elected representative is a woman, as they believe that female leaders are more responsive to their concerns and priorities.[60] This ensures that the policy priorities of women who would otherwise not partake in decision-making are addressed. Studies have also indicated that electoral constituencies designated for women leaders experience an increased provision of civic amenities, schools, healthcare facilities, and fair-price shops.[61] In a 2010 study as part of the India Policy Forum organised by the National Council of Applied Economic Research, it was observed that villages led by women had a noticeable rise in female engagement and a greater level of attentiveness to issues related to women’s policies. The research also revealed that village councils with women in reserved leadership positions allocated greater resources to improve infrastructure for drinking water, sanitation, roads, school maintenance, health centre upkeep, and irrigation facilities.[62] The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the role of women’s leadership during a crisis. A survey revealed that a sizeable section of EWRs were engaged in identifying returning migrants and spreading awareness about the disease, while arranging rations, hospital beds for patients, and providing urgent medical support for pregnant women.[63] Several institutions and organisations[h] have initiated trainings for women members of local government to improve their attitudinal dynamics, skill development, and knowledge/awareness levels.[64] These interventions have proven to be very effective in creating motivation and awareness among panchayat-level women leaders.[65] Data also suggests that despite several limitations, women leaders proved to be faster learners in managing local administrative structures than men.[66]

Women’s entry into non-traditional spaces and their ability to negotiate and influence decisions have impacted rigid gender norms. Many EWRs report a change in confidence levels, and in their status within their family and in the community after getting elected. They have also influenced the aspirations of families, as parents invest more in girls’ education when there are female role models in politics.[67] Additionally, EWRs are role models for other women in their communities and often spur women to participate in politics.

A 2012 study found a crucial link between political representation in local rural governments and crimes against women. There was an increase in documented crimes against women after an increase in the political representation of women, driven by a surge in reporting of crimes where there are female representatives.[68] A 2021 survey in Bihar found that EWRs play a key role in providing redressal support on issues of domestic violence and child marriage; 61 percent of EWRs reported that they intervened to stop abuse reported by women in their constituencies, and 46 percent had intervened to stop child marriage. However, most women leaders were reluctant to talk openly about it because of prevalent social norms.[69]

Challenges and Barriers to Participation

Despite the documented impacts of having more women representatives in local decision-making roles, EWRs face extensive challenges to join and then continue participating in local governance:

Many women have drawn attention to the policy of rotating reserved seats[i] every five years as a barrier.[70] Rotation aims to bring in as many excluded groups and individuals as possible into the system. But this also means that women candidates cannot gain from their experience from one term to the next, and many return to their caregiving roles at home after a single term. Elected male representatives were found to be more likely to contest elections more than once than elected women.[71] Women are usually not given the chance to contest from general unreserved seats as this decision mostly lies with the concerned political party or with senior male members of the household. Male-dominated political circles often view women candidates as less likely to win elections than men, resulting in political parties giving them fewer tickets.[72] Even women from political dynasties are more likely to be given ‘safe’ seats—those previously occupied by a male family member—where their win is mostly assured.[73] Recent data, however, belies this notion; certain election results show that women candidates have equal, if not higher, chances of winning than male candidates.[74] However, due to deeply entrenched prejudice against women leaders, they could not extend their administrative experience gained from one term to another one.[75]

Most women representatives report facing gender-based discrimination and feeling ignored in the panchayat owing to their gender.[76] Administrative roles, like that of panchayat secretary and other posts, are dominated by men. Most first-time EWRs find it difficult to deal with block and district administration and police officials, due to limited exposure to public life. As such, male representatives or leaders related to the women members play a more dominant role in interactions with external bodies and actors. A major apprehension remains that in many regions across India, women leaders in reserved seats are elected as proxy candidates who are controlled by male members of their family and community.[77] A 2021 study indicates that 77 percent of the interviewed EWRs believe that they cannot change things easily in their constituencies due to societal challenges.[78] Surveys have also revealed that women leaders receive less favourable assessments from their constituents than men—respondents appeared to be significantly less satisfied with the quality of services when the pradhan is a woman. Women who are elected to reserved seats tend to have a lower economic status compared to their male counterparts, along with less experience, lower educational qualifications, and a lower likelihood of being literate. Voters may factor in these attributes when evaluating the quality of their leaders. Additionally, it is possible that villagers may believe that women may be less effective as leaders and are hesitant to change this belief even when confronted with factual evidence.[79] A majority of women representatives do not contest another election, while many of those who do contest are unable to get re-elected, possibly due to societal prejudices and structural disadvantages. Former EWRs said they felt that administrative work in panchayats was unsuitable for women and that they had felt incompetent in executing their responsibilities, often discouraging them from seeking re-election. Many also expressed that they were unable to maintain the balance between work and household chores due to resistance from their spouses or families. Notably, in a 2019 survey from Uttar Pradesh, women had significantly less knowledge about political institutions and electoral rules. Despite 30 years of gender quotas, 27 percent of women gave the wrong answer to the question of whether women can become panchayat members, by answering ‘no’. The same survey showed that women in villages with female pradhans are 6 percentage points more likely to try meeting with the pradhan to raise their problems.[80] This shows that gender-based biases still persist.

The gender digital divide, which predominantly affects women in rural India, hampers the work of women representatives.[81] This is relevant as local governments are adopting more digitisation nationwide for public service delivery and redressal. A survey conducted in Bihar showed that only 63 percent of EWR participants owned a phone, with only 24 percent of them having smartphones.[82] Low digital literacy among women remains a major hurdle for women leaders in discharging their administrative functions more efficiently in the panchayats.[83]

Some states (such as Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana) follow the ‘two-child’ norm,[j] barring candidates with more than two children from contesting PRI elections. The Supreme Court has also validated this legal provision.[84] States like Haryana and Rajasthan have also set minimum education qualifications for candidates. These policies inadvertently restrict women’s entry into politics as they are likely to lack access to education and choices in family planning.[85] Women leaders at the panchayat level have also expressed their concern over being adversely impacted due to such provisions.[86]

While the provision for reservation of seats for women in panchayats has facilitated greater participation of women at the grassroots level in India, there are certain persisting challenges for women representatives that need to be addressed through institutional reforms, greater investment in capacity building, and socio-cultural transformations. The following recommendations are aimed at furthering a more robust participation of women in local politics in India’s villages.

Well-trained EWRs are able to handle their roles and responsibilities independently. There has been a significant improvement in capacity-building and training programmes for newly-elected female representatives through government training institutes in partnership with civil society organisations. However, there is a need to scale up and reinforce such training at regular intervals. There is also a need to monitor the quality of these programmes. Emphasis must be given to skilling women on digital technology to increase their efficiency in panchayat responsibilities. Notably, the number of queries raised by women representatives in training sessions is lower than those by male representatives, due to their hesitation to speak in public.[87] Therefore, there is a need to ensure conducive environments for training where women members feel comfortable to engage in discussions.

Across states, women’s SHGs have been noted to support the work of women representatives in improving the reach and quality of public service delivery.[88] Many women who contest elections have a background in the SHG movement. Indeed, a 2021 study has shown that involvement in SHGs has a significant impact on women's political participation since it provides them with larger networks and the capacity for collective action, and helps develop their civic skills.[89] This convergence has been particularly successful in Kerala, where the Kudumbashree programme has played a part in the success of development initiatives by panchayats. More such collaborative endeavours of government and SHGs can facilitate greater political agency in women and ensure higher participation in local politics.

Although data suggests a high participation of women in panchayats, on-ground reports indicate that, in many cases, male members continue to control women functionaries, subverting their political agency by using them as rubber stamps. Local administrations in the respective states need to establish an institutionalised mechanism to monitor the work of women representatives to ensure they are able to discharge their functions without any interference from male members of the community. Also, the safety of women candidates and representatives must be ensured so that fear of violence does not deter women from contesting local polls. Government-initiated awareness drives and campaigns at the village level could help change conservative perceptions about women’s participation in politics.

Data indicates that women representatives typically belong to lower economic groups compared to men, and they suffer from financial constraints both as contestants and as representatives.[k],[90] Provisions for state funding for women contestants belonging to economically weaker households or support from political parties would allow more women to contest panchayat elections and seek re-election. Greater financial remuneration for EWRs could also incentivise them to take part in the panchayat activities with greater interest despite multiple societal hindrances.

In states such as Uttarakhand and Karnataka, federations of EWRs have emerged as an effective tool and platform for improving the functioning of women representatives and bringing a greater focus on the issues and challenges faced by women in local governance.[91] These federations should be nurtured and strengthened. Importantly, the ‘rotation of reserved seats’ provision should be altered to allow two-term reservation of seats.[92] Additionally, recruiting more women as panchayat officials apart from elected representatives, and conducting gender sensitisation programmes for government officials and elected male representatives at all levels of PRIs would create a viable working environment for EWRs.

Although state-level macro data on EWRs in village panchayats is available, certain districts and regions do not have coherent updated data, hampering the ability to conduct holistic and fully informed assessments. The availability of comprehensive disaggregated data on the challenges faced by EWRs is important to ensure the numerically higher and qualitatively better representation of women at the panchayat level of politics across India. Such data is crucial to devise targeted policy interventions to tackle the structural hindrances that inhibit increased women’s representation in panchayat politics.

The provision of reserved seats for women at the local level of government in India has resulted in the political empowerment of women at the grassroots across the country. Indeed, India is among the top-ranked countries for facilitating women's political participation at the local level. However, there is much to be done, particularly to address the existing gaps and challenges in ensuring the meaningful representation of women in local government structures. Institutional and administrative reforms, skills development and capacity-building programmes, and ensuring the availability of comprehensive data will pave the way to strengthen the political agency of women and encourage their equitable participation in India's electoral politics.

[a] Notably, the 74th Amendment Act, which also reserved one-third of seats for women, is not being studied in this paper as it involves provisions for the empowerment of local self-government in urban areas (municipal bodies), which is beyond the scope of this paper.

[b] PRIs are gram panchayats (village-level councils), panchayat samitis (block-level councils), and zilla parishads (district-level councils).

[c] SDG target 5.5: “Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life”.

[d] Telephonic and in-person interviews of select women representatives along with other women gram panchayat members were conducted. Their insights on the opportunities, challenges, and overall experiences of women representatives at the panchayat level are incorporated in this paper. The authors consulted a few select government functionaries, self-help groups, and civil society organisations working closely with PRIs to get their perspective on the impact of reservation policy for women’s representation at the panchayat level.

[e] The municipal laws in Nagaland did not provide for women’s reservation until 2005. However, tribal groups continue to refuse to implement the reservation. Mizoram does not have the panchayat system. The local government in Mizoram is formed by Autonomous District Councils, with no reservation for women. The Dorbar Shnongs, the traditional village-level institutions of the Khasis of Meghalaya, have not allowed women to contest elections. Earlier, women were barred from attending Dorbar Shnong meetings and could only be represented by an adult male family member. Given the powerful status of the Dorbars, most women shy away from speaking openly against them.

[f] PRIA, established in 1982, is a global centre for participatory research and training focused on empowering citizens through information and mobilisation and, at the same time, sensitising government agencies towards citizen needs.

[g] India has around 12 million SHGs, 88 percent of which have only women members. SHGs create collective capacity by strengthening women economically, socially, and politically, empowering them through various pathways such as familiarity with handling money, financial decision-making, improved social networks, asset ownership, and livelihood diversification. For more, see: Sreeparna Chakrabarty, “Self Help Groups can help in widening women’s labour force participation: Economic Survey 2022-23,” The Hindu, January 31, 2023.

[h] These include the National Institute of Rural Development, Kerala Institute of Local Administration, Sardar Patel Institute of Public Administration’s Centre for Panchayat Training, NGOs like UNNATI, Ahmedabad Study Action Group, Institute of Social Science Trust, SUTRA, Society for Participatory Research in South Asia, and the Young Women’s Christian Association.

[i] According to Article 243D (1) and (3) of the Constitution, the reserved seats may be allotted by rotation to different constituencies within a panchayat.

[j] The ‘two-child’ norm, a governmental effort to encourage birth control measures, states that a person with more than two children will be disqualified from contesting election as a sarpanch or a member. For more, see: “Two Child Policy in Indian States”, The Indian Express, October 23, 2019.

[k] Women, especially in the rural areas, are financially weaker than men due to lack of employment opportunities, lower wages, and rigid socio-cultural norms that largely keeps women confined to their homes. For more, see: Atul Thakur, “Women paid less than men for same work in towns and villages”, Times of India, March 19, 2023, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/98762052.cms?from=mdr&utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

[1] Kevin Kruse, “New Research: Women more effective than men in all leadership measures,” Forbes, March 31, 2023,

[2] Sarah Childs & Mona Lena Krook, “Critical Mass Theory and Women’s Political Representation,” Political Studies: 2008 VOL 56, 725–736, https://mlkrook.org/pdf/childs_krook_2008.pdf.

[3] “SDG 5: Gender Equality,” UNStats, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/Goal-05/#:~:text=Quotas%20also%20contribute%20to%20higher,of%20management%20positions%20in%202021

[4] UN Women, “Women in Local Government,” https://localgov.unwomen.org/.

[5] Ministry of Panchayati Raj, “State/UT-Wise Details of Elected Representatives & EWRs,” https://panchayat.gov.in/state-ut-wise-details-of-elected-representatives-ewrs/; “Women in Panchayati Raj Institutions: Successful for some, barriers for many,” Outlook, September 20, 2023, https://www.outlookindia.com/national/women-in-panchayati-raj-institutions-successful-for-some-barrier-for-many-news-319213

[6] World Economic Forum, “Global Gender Gap Report 2023,” June 2023, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2023.pdf.

[7] Ionica Berevoescu, and Julie Ballington, “Women’s Representation in Local Government: A Global Analysis,” UN Women, December 2021, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/Womens-representation-in-local-government-en.pdf.

[8] Zohal Hessami and Mariana Lopes da Fonseca, “Female Political Representation and Substantive Effects on Policies: A Literature Review,” IZA Institute of Labour Economics, Discussion Paper Series, April 2020, IZA DP No. 13125.

[9] Ionica Berevoescu and Julie Ballington, “Women’s Representation in Local Government: A Global Analysis,” UN Women, December 2021, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/Womens-representation-in-local-government-en.pdf.

[10] “India - Summary Report - National Family Health Survey 1992-93,” International Institute for Population Studies Bombay, The DHS Program, 1995, https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR162/SR162.pdf.

[11] “National Family Health Survey - 5 2019-21”, International Institute for Population Sciences, https://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5_FCTS/India.pdf.

[12] Anjani Datla, “Women as Leaders: Lessons from Political Quotas in India,” National Bureau of Economic Research, 2009, http://users.nber.org/~rdehejia/!@$devo/Lecture%2009%20Gender/gender%20and%20politics/HKS763-PDF-ENG2.pdf.

[13] T.R.Raghunandan, “Re-Energizing Democratic Decentralization in India,” Rethinking Public Institutions in India, May 18, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199474370.003.0012.

[14] Esther Duflo, and Petia Topalova, “Unappreciated Service: Performance, Perceptions, and Women Leaders in India,” October 2004, https://poverty-action.org/sites/default/files/publications/unappreciated.pdf.

[15] “Economic Survey Highlights Thrust on Rural Development,” PIB Delhi, January 31, 2023, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1894901.

[16] “Panchayat: A Knowledge hub”, PRIA, https://www.pria.org/panchayathub/knowledgeresources.

[17] Esther Duflo, “Women Empowerment and Economic Development,” Journal of Economic Literature, December 2012, Vol. 50, No. 4, pp. 1051-1079; Nafisa Halim, Kathryn M. Yount, Solveig A. Cunningham and Rohini P. Pande, “Women’s Political Empowerment and Investments in Primary Schooling in India,” Social Indicators Research, February 2016, Vol. 125, No. 3, pp. 813-851.

[18] Peter Ronald deSouza, “Multi-State Study of Panchayati Raj Legislation and Administrative Reform,” Background Papers, September 27, 2000, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/958641468772791330/pdf/280140v130IN0Rural0decentralization.pdf.

[19] “Report On The Committee On The Status Of Women In India,” Ministry of Education and Social Welfare, Government of India, December 1974, https://pldindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Towards-Equality-1974-Part-1.pdf.

[20] Ashok Mehta, “Report of the Committee on Panchayati Raj Institutions,” Government of India, 1978. https://indianculture.gov.in/reports-proceedings/report-committee-panchayati-raj-institutions.

[21] Sharmila Chandra. “National Perspective Plan for Women Makes No Headway,” India Today, November 7, 2013, https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/indiascope/story/19890930-national-perspective-plan-for-women-makes-no-headway-816578-1989-09-29;

Nandini Prasad, “Training needs to women in Panchayats: An Overview,” UNESCO House, 1998.

[22] Raghabendra Chattopadhyay and Esther Duflo, “Women as Policy Makers: Evidence from a Randomized Policy Experiment in India,” Econometrica, September 2004, Vol. 72, No. 5, pp. 1409-1443.

[23] Chattopadhyay and Duflo, “Women as Policy Makers: Evidence from a Randomized Policy Experiment in India”.

[24] “The Constitution (Seventy-Third Amendment) Act, 1992| National Portal of India”, Government of India, December 13, 2023, https://www.india.gov.in/my-government/constitution-india/amendments/constitution-india-seventy-third-amendment-act-1992.

[25] Rajesh Kumar Sinha, “Women in Panchayats,” Kurukshetra, 2018, https://www.pria.org/uploaded_files/panchayatexternal/1548842032_Women%20In%20Panchayat.pdf.

[26] Anuja, “India: 25 Years on, Women’s Reservation Bill Still Not a Reality.” Al Jazeera, September 9, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/8/25-years-india-women-reservation-bill-elected-bodies-gender.

[27] Madhu Joshi and Devaki Singh, “77% women in Panchayati Raj Institutions believe they can’t change things easily on ground,” The Print, April 24, 2021, https://theprint.in/opinion/77-women-in-panchayati-raj-institutions-believe-they-cant-change-things-easily-on-ground/644680/.

[28] Press Trust of India, December 1, 2021, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1776866#:~:text=However%2C%20as%20per%20the%20information,Uttarakhand%20and%20West%20Bengal%2C%20have

[29] Ashim Mukhopadhyay, “Kultikri: West Bengal's Only All-Women Gram Panchayat,” Economic and Political Weekly, June 3, 1995, Vol. 30, No. 22, pp. 1283-1285.

[30] Jitendra, “Democracy’s Better Half,” Down To Earth, December 15, 2014, https://www.downtoearth.org.in/coverage/democracys-better-half-47642.

[31] PRIA, “How to Conduct Mahila Sabhas?,” 2018, https://www.pria.org/knowledge_resource/1564115720How%20to%20conduct%20Mahila%20Sabhas_English.pdf

[32] Sarika Malhotra, “Ground Report: Is Reservation for Women in Panchayats Working at the Grassroot Level?”, Business Today, August 26, 2014, https://www.businesstoday.in/magazine/cover-story/story/bihar-women-panchayats-mgnrega-indira-awas-yojana-137007-2014-08-21; Neetu Singh, "A Gram Pradhan Has Several Responsibilities. How Can a Woman Be Expected to Handle It?,” Gaon Connection, March 14, 2020, https://en.gaonconnection.com/the-curious-case-of-female-gram-pradhan-and-their-male-representatives-who-are-their-husbands-sons-or-fathers-in-laws-yes-its-quite-common/; Uttara Chaudhuri and Mitali Sud, “Women as Proxies in Politics: Decision Making and Service Delivery in Panchayati Raj,” The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, October 16, 2015, https://www.thehinducentre.com/the-arena/current-issues/women-as-proxies-in-politics-decision-making-and-service-delivery-in-panchayati-raj/article64931527.ece#Six; Siddhartha Mukerji, “Social Roots of Local Politics: Women Contestants in the Panchayat Elections of Uttar Pradesh (2015),” Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 28(1) 113–126, 2021.

[33] Jiby J Kattakayam, “50% Women’s Reservation in Kerala Local Body Polls and the Diminution of a Male Bastion,” The Times of India, December 2, 2020, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/jibber-jabber/50-womens-reservation-in-kerala-local-body-polls-and-the-diminution-of-a-male-bastion/.

[34] Sanchita Hazra, “Women Participation in Panchayat Raj in West Bengal: An Appraisal,” Economic Affairs 62, no. 2 (2017): 347. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-4666.2017.00019.5.

[35] “With ‘Kudumbasree’ Training, Young Kerala Women Script History,” Daijiworld, September 24, 2023, https://www.daijiworld.com/news/newsDisplay?newsID=1123585.

[36] B. Devi Prasad and S. Haranath, “Participation of Women and Dalits in Gram Panchayat,” Journal of Rural Development 23 (3): 297–318, 2004.

[37] B. Devi Prasad and S. Haranath, “Participation of Women and Dalits in Gram Panchayat”

[38] Pareena G. Lawrence and Kavita Chakravarty, “Life Histories of Women Panchayat Sarpanches from Haryana, India: From the Margins to the Center,” Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017.

[39] D.P. Singh, “Impact of 73rd Amendment Act on Women’s Leadership in the Punjab,” International Journal of Rural Studies 15 (1): 1–8, 2008.

[40] Shubhomoy Sikdar, “In Madhya Pradesh Panchayats, Husbands of Elected Women Taking Oath,” The Hindu, August 8, 2022, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/male-family-member-take-oath-on-behalf-of-women-in-mp/article65742124.ece.

[41] Hiral Dave, “Husbands Make Most of Gujarat’s 50% Reservation for Women in Local Bodies,” Hindustan Times, February 3, 2017, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/husbands-make-most-of-gujarat-s-50-reservation-for-women-in-local-bodies/story-JBJEf5unFrZrnHr2xp1niO.html.

[42] Uma Mahadevan-Dasgupta, “Why Women Are the Game-Changers in Local Governments,” The Hindu, August 24, 2022. https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/why-women-are-the-game-changers-in-local-governments/article65804634.ece.

[43] Nirmala Buch, “Women’s Experience in New Panchayats: The Emerging Leadership of Rural Women,” Centre for Women’s Development Studies, Occasional Paper No. 35. 2000.

[44] Pareena G. Lawrence and Kavita Chakravarty, Life Histories of Women Panchayat Sarpanches from Haryana, India: From the Margins to the Center, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017.

[45] Maninder Dabas, “8 Women Sarpanch Who Are Leading by Examples And Turning The Fortunes Of Indian Villages,” India Times, August 22, 2023, https://www.indiatimes.com/news/india/meet-these-eight-women-sanpanches-who-defied-patriarchy-and-are-doing-great-work-for-their-villages-344199.html.

[46] Nisha Velappan Nair, and John S. Moolakkattu, “Gender-Responsive Budgeting: The Case of a Rural Local Body in Kerala,” SAGE Open, 8, no. 1, January 2018, https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017751572.

[47] B. Aravind Kumar. “Women Need Greater Say in Panchayats,” The Hindu, June 24, 2022, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/women-need-greater-say-inpanchayats/article65532803.ece.

[48] “Study on EWRs in Panchayati Raj Institutions,” Ministry of Panchayati Raj, Government of India, 2008, https://accountabilityindia.in/sites/default/files/document-library/330_1260856798.pdf.

[49] Nirmala Buch, “Women’s Experience in New Panchayats: The Emerging Leadership of Rural Women.” Centre for Women’s Development Studies, https://www.cwds.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/WomensExperiencePanchayats.pdf.

[50] “Study on EWRs in Panchayati Raj Institutions,” Ministry of Panchayati Raj, Government of India, 2008.

[51] Nirmala Buch, “Women’s Experience in New Panchayats: The Emerging Leadership of Rural Women,” Centre for Women’s Development Studies, Occasional Paper No. 35. 2000.

[52] Neetu Singh, “A Gram Pradhan Has Several Responsibilities. How Can a Woman Be Expected to Handle It?” Gaon Connection, March 14, 2020, https://en.gaonconnection.com/the-curious-case-of-female-gram-pradhan-and-their-male-representatives-who-are-their-husbands-sons-or-fathers-in-laws-yes-its-quite-common/

[53] “Study on the Impact of Women GP Adhyakshas on Delivery of Services and Democratic Process”, Centre for Budget and Policy Studies, July 2015, https://cbps.in/wp-content/uploads/EWR_Final.pdf.

[54] “Women’s Reservation Bill: The Issues to Consider,” The Wire, September 20, 2023. https://thewire.in/government/womens-reservation-bill-the-issues-to-consider.

[55] Siddhartha Mukerji, “Social Roots of Local Politics: Women Contestants in the Panchayat Elections of Uttar Pradesh,” Indian Journal of Gender Studies, Volume 28, Issue 1, 2015.

[56] Chanpreet Khurana, “Women Panchayat Leaders Find Their Voice,” The Mint, September 21, 2015, https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/XIVFC4NFGZHmaNWeKOYqnM/Women-panchayat-leaders-find-their-voice.html

[57] Lori Beaman, Esther Duflo, Rohini Pande, and Petia Topalova, “Political Reservation and Substantive Representation: Evidence from Indian Village Councils,” India Policy Forum, 2010–11, https://www.ncaer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/4_Lori-Beaman_Esther-Duflo_Rohini-Pande_Petia-Topalova.pdf.

[58] Raghabendra Chattopadhyay and Esther Duflo, “Women as Policy Makers: Evidence from a Randomized Policy Experiment in India,” Econometrica , Sep., 2004, Vol. 72, No. 5, pp. 1409-1443.

[59] “Sakshamaa Briefing Paper - Women Political Leaders in Rural Bihar: Striving for Change Amidst Socio- Cultural Restrictions,” Centre for Catalyzing Change, 2021, https://www.c3india.org/uploads/news/Briefing_Paper_EWR_Survey_22032021.pdf.

[60] “Decentralisation – The Path to Inclusive Governance?” Accountability Initiative, January 2010, https://accountabilityindia.in/sites/default/files/policy-brief/panchayatbrief1.pdf.

[61] Madhu Joshi and Devaki Singh, “77% women in Panchayati Raj Institutions believe they can’t change things easily on ground,” The Print, 24 April, 2021, https://theprint.in/opinion/77-women-in-panchayati-raj-institutions-believe-they-cant-change-things-easily-on-ground/644680/.

[62] Vidhatri Rao. “‘Sarpanch Pati’: The Small Steps, and Giant Leaps of Women’s Reservation,” The Indian Express, August 11, 2022. https://indianexpress.com/article/political-pulse/sarpanch-pati-madhya-pradesh-women-representatives-oath-reservation-8084346/.

[63] Madhu Joshi, and Devaki Singh, “77% Women in Panchayati Raj Institutions Believe They Can’t Change Things Easily on Ground,” The Print, April 24, 2021. https://theprint.in/opinion/77-women-in-panchayati-raj-institutions-believe-they-cant-change-things-easily-on-ground/644680/.

[64] “Training Programme Launched for Elected Women Representatives,” The Times of India, April 17, 2017, https://m.timesofindia.com/good-governance/centre/training-programme-launched-for-elected-women-representatives/amp_articleshow/58224613.cms.

[65] “A Case Study on Women Leadership in Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRI) at the Gram Panchayat Level,” NIRDPR, http://nirdpr.org.in/nird_docs/casestudies/cord/cord1.pdf.

[66] Nandini Prasad, “Training needs to women in Panchayats: An Overview,” UNESCO House, 1998.

[67] Anjani Datla, “Women as Leaders: Lessons from Political Quotas in India,” John F. Kennedy School of Government (HKS), Harvard University, January 2012, http://users.nber.org/~rdehejia/!@$devo/Lecture%2009%20Gender/gender%20and%20politics/HKS763-PDF-ENG2.pdf.

[68] Lakshmi Iyer, Anandi Mani, Prachi Mishra, and Petia Topalova. “The Power of Political Voice: Women’s Political Representation and Crime in India,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4, no. 4 (October 1, 2012): 165–93. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.4.4.165.

[69] Centre for Catalyzing Change, “Sakshamaa Briefing Paper - Women Political Leaders in Rural Bihar: Striving for Change Amidst Socio- Cultural Restrictions,” C3 India, 2021, https://www.c3india.org/uploads/news/Briefing_Paper_EWR_Survey_22032021.pdf

[70] Nupur Tiwari, “Rethinking the Rotation Term of Reservation in Panchayats”, Economic and Political Weekly, January 31, 2009, https://www.epw.in/journal/2009/05/commentary/rethinking-rotation-term-reservation-panchayats.html

[71] Nupur Tiwari, “Rethinking the Rotation Term of Reservation in Panchayats,” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 44, No. 5, January 31, 2009, pp. 23-25

[72] Rajeshwari Deshpande, “How Gendered was Women’s Participation Women in Election 2004?” Economic and Political Weekly, 39(51): 5431–6, 2004.

[73] Carole Spary, “Women Candidates and Party Nomination Trends in India–Evidence From the 2009 General Election,” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 52(1):109–138, 2014; Wendy Singer, ’A Constituency Suitable For Ladies’: And Other Social Histories of Indian Elections, Oxford University Press, 2007

[74] “Where Are the Women in Indian Politics?,” EPW Engage, ISSN (Online) – 2349-8846, May 3, 2019

[75] Nupur Tiwari, “Rethinking the Rotation Term of Reservation in Panchayats”

[76] Neeta Hardikar, “What women need to succeed in panchayat elections,” IDR Online, December 5, 2023, https://idronline.org/article/gender/what-women-need-to-succeed-in-panchayat-elections/

[77] Vidhatri Rao. “‘Sarpanch Pati’: The Small Steps, and Giant Leaps of Women’s Reservation,” The Indian Express, August 11, 2022, https://indianexpress.com/article/political-pulse/sarpanch-pati-madhya-pradesh-women-representatives-oath-reservation-8084346/.

[78] “Sakshamaa Briefing Paper - Women Political Leaders in Rural Bihar: Striving for Change Amidst Socio- Cultural Restrictions,” C3India., 2021, https://www.c3india.org/uploads/news/Briefing_Paper_EWR_Survey_22032021.pdf.

[79] “Study on EWRs in Panchayati Raj Institutions,” Ministry of Panchayati Raj, Government of India, 2008

[80] Lakshmi Iyer and Anandi Mani, “The Road Not Taken: Gender Gaps along Paths to Political Power,” Ideas For India, May 21, 2019, https://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/social-identity/the-road-not-taken-gender-gaps-along-paths-to-political-power.html.

[81] Akshay Atmaram Tarfe, “Women, Unemployed, Rural Poor Lagging Due to Digital Divide: Oxfam India Report,” Oxfam India, 2022, https://www.oxfamindia.org/press-release/women-unemployed-rural-poor-lagging-due-digital-divide-oxfam-india-report.

[82] Centre for Catalyzing Change, “Sakshamaa Briefing Paper - Women Political Leaders in Rural Bihar: Striving for Change Amidst Socio- Cultural Restrictions.” C3India, 2021, https://www.c3india.org/uploads/news/Briefing_Paper_EWR_Survey_22032021.pdf.

[83] Neeta Hardikar, “What Women Need to Succeed in Panchayat Elections,” India Development Review, December 5, 2023, https://idronline.org/article/gender/what-women-need-to-succeed-in-panchayat-elections/.

[84] Dhananjay Mahapatra, “2-child norm valid even if 3rd given for adoption: SC,” The

Times of India, October 25, 2018, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/66355638.cms?from=mdr&utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

[85] Tanushree Gupta, Susobhan Maiti, Meenakshi Y, and Anindita Jana, “Gender Gap in Internet Literacy in India: A State-Level Analysis, ” Research Square, April 26, 2023, https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-2846253/v1/7cffcd82-6a7d-4bf8-b6a8-3b87159b8410.pdf?c=1682488847.

[86] Legal Correspondent, “Govt. Can’t Punish Us for Lack of Education: Women on Haryana New Poll Law,” The Hindu, October 8, 2015, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/women-candidates-hit-back-at-haryanas-new-poll-law-on-education-qualification/article7735734.ece.

[87] Nandini Prasad, “Training needs of women in Panchayats: An Overview,” UNESCO, 1998

[88] Sushmita Mukherjee, “Empowering Women in India through Self-Help Groups,” Global Communities, April 2022, https://globalcommunities.org/blog/empowering-women-in-india-through-self-help-groups/.

[89] Soledad Artiz Prillaman, “Strength in Numbers: How Women’s Groups Close India’s Political Gender Gap,” American Journal of Political Science 67, no. 2 (September 14, 2021): 390–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12651.

[90] “Women’s Leadership in Panchayati Raj Institutions: An analysis of six states (Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Kerala, Maharashtra, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh),” PRIA, November 1999,

[91] “Strengthening Women’s Leadership”, Parivartan, http://www.parivartan.org.in/Programs/Women%20Leadership.html.

[92] Nupur Tiwari, “Rethinking the Rotation Term of Reservation in Panchayats”.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sunaina Kumar is Director and Senior Fellow at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at the Observer Research Foundation. She previously served as Executive Director ...

Read More +

Ambar Kumar Ghosh is an Associate Fellow under the Political Reforms and Governance Initiative at ORF Kolkata. His primary areas of research interest include studying ...

Read More +