Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV)[a] or violence against women and girls is regarded as a global pandemic that affects one in every three women across their lifetime. An estimated 736 million women become victims of intimate partner violence (IPV), or non-partner sexual violence, or both, at least once in their life.[1] The international community has long acknowledged the severity of the problem. In 1995, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action called for the elimination of violence against women.[2] A decade later, in 2015, the UN adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which included a global target to eliminate “all forms of violence against women and girls in public and private spheres.”[3] In 2016, the World Health Assembly Resolution 69.5 called for a global plan of action to strengthen the role of the health system within a national multisector response to address interpersonal violence, particularly against women and young girls.[4] Despite all these mandates, however, 49 countries have yet to adopt a formal policy on domestic violence.[5]

This violence—which has serious short- and long-term consequences on women’s health and well-being—[6] disproportionately affects women in low- and lower-middle-income countries. Women aged 15-49 years living in the least developed countries have a 37-percent lifetime prevalence of domestic violence.[b],[7] Among younger women (15-24), the risk is even higher, with one of every four women who have ever been in a relationship facing some form of violence.

Indeed, domestic violence is an all-pervasive public-health concern that women face in various forms across different parts of the world.[8] In England, for example, the 2020 Crime Survey reported a 9-percent increase from 2019 in domestic-abuse related crimes.[9] In the United States (US), the number of women who have ever reported experiencing domestic violence increased by 42 percent from 2016 to 2018.[10] In India, 30 percent of women have experienced domestic violence at least once from when they were aged 15, and around 4 percent of ever-pregnant women have experienced spousal violence during a pregnancy.[11]

This paper studies the link between domestic violence and women’s sexual and reproductive health, across their life course.[12] Existing literature point to a significant association between domestic violence, and the poor health and well-being of not only the women themselves, but the children they give birth to, and are expected by social norms to care for. Indeed, the impacts of violence against women lead to grave demographic consequences, including low educational attainment and reduced earning potential for the younger generations.[13],[14],[15]

A 2017 study of India, Nepal, and Bangladesh found GBV to be a risk factor for unintended pregnancies among adolescent and young adult married women.[16] Studies from different countries have also suggested moderate to strong positive associations between IPV and clinical depression.[17] These analyses noted an increased risk of two- to three-fold in depressive disorders and 1.5- to two-fold increased risk of elevated depressive symptoms and post-partum depression among women who have been subjected to intimate-partner violence. These women reported more episodes of anxiety and depression, and increased risk of low birth weight babies, pre-term delivery, and neonatal deaths.[18],[19] In one 2005 study, South Asian women in the US reported that domestic violence reduced their sexual autonomy and increased their risk for unintended pregnancy; many suffered abortions.[20] A recent review, in 2020, of women from the US, India, Brazil, Tanzania, Spain, Sweden, Norway, Australia and Hong Kong found that domestic violence was associated with an increased risk of shortened duration of breastfeeding.[21]

Studies from Bangladesh and Nepal show the association between violence and women’s poor nutritional status, increased stress, and poor self-care.[22],[23] Also in Bangladesh, demographic health surveys show compromised growth in children born to women suffering domestic violence.[24] In India, domestic violence has been found to impact early childhood growth and nutrition through biological and behavioural pathways.[25] Another analysis of 2012-13 data from Pakistan showed a significant increase in underweight, stunting, and wasting among children of women subjected to domestic violence.[26]

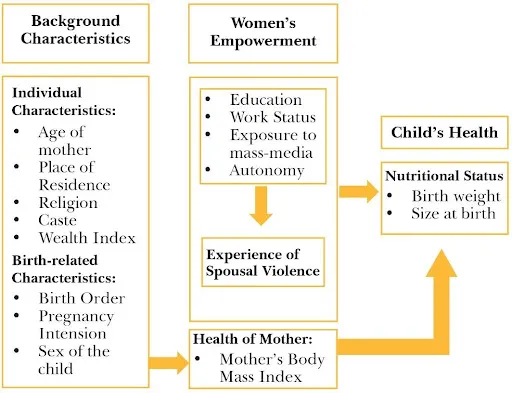

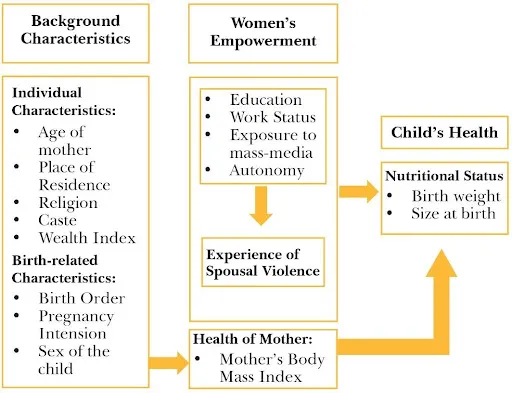

There is no dearth, therefore, in evidence that shows a direct causal relationship between domestic violence and the growth and development of children.[27] (See Figure 1).[28]

Figure 1: Conceptual framework: Spousal violence and Children’s nutritional status

Source: Sinha & Chattopadhyay et al, Social Criminology, 2017[29]

Domestic Violence in India

Historically, domestic violence was understood as a concerning threat to women’s lives in India driven by the Dowry system. Therefore, the earliest legislations in the country to stop violence leading to so-called “dowry deaths” were implemented through an amendment to the Dowry Prohibition Act (1961). Section 304B of the Indian Penal Code criminalised any form of violence with respect to dowry demands by a husband or in-laws.[30] As feminist scholarship and activism evolved, inter-disciplinary studies gave more clarity to the multi-faceted range of causes of spousal and family violence and their impacts on women. Through the years, domestic violence has remained among the gravest threats to women in India, despite being defined as a criminal offence under section 498-A of the Indian Penal Code in 1983.[31],[32] A dedicated civil law, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDV), was eventually introduced to provide immediate relief to aggrieved women in a household who may be subjected to abuse by their husbands and in-laws.[33] Today domestic violence continues to be a widespread occurrence across India, cutting across caste, class, religion, age, and education.[34]

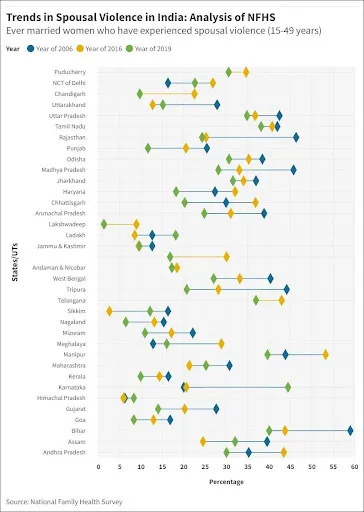

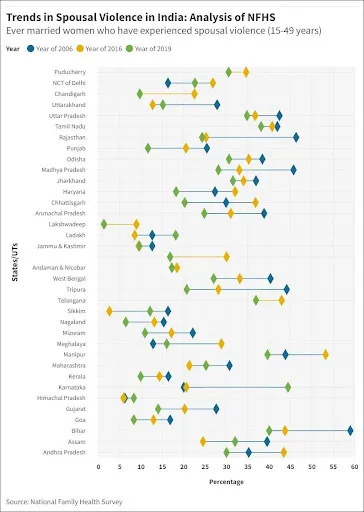

NFHS surveys from 2006 to 2019 have found consistently increasing incidence of spousal violence in India, particularly in certain regions (See Figure 2). States like Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Maharashtra, and newly formed union territories (UTs) of Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh showed a declining pattern during 2015-16, only to increase markedly again in 2019. There are states like Karnataka, for example, which are particularly concerning for the persistently increasing percentage of women experiencing domestic violence. Recent data on states from the fifth NFHS (2019-21) show the states that continue to have the highest rates of spousal violence in the country: Karnataka, Bihar, and Manipur.

Figure 2: Spousal Violence among married women (15-49 years) in India

The Cascading Impacts of COVID-19

At the time of writing this paper, the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic has cost 5 million lives and infected more than 300 million across the globe. It has caused a massive economic fallout, with countries still reeling from the lockdowns and halt in economic activity. The humanitarian impacts of the pandemic have also been huge. It caused what experts call a “shadow pandemic”[c]—that of increased exposure to abuse and violence during the successive lockdowns and disruptions to vital support services. Economic instability, threatened livelihoods, increased levels of stress due to the double burden of care and household duties, have further intensified the risks.[35] In some countries, there has been as high as a 30-percent increase in reported domestic violence.[36]

Indeed, the pandemic has called attention to the importance of addressing violence against women as a public-health priority. Yet, this rise in family and domestic violence is not a unique impact of the Covid-pandemic. Historically, as social infrastructures break down during disasters and crises, women suffer the additional burden of increased domestic violence. For example, Sierra Leone saw a rise of 19 percent in gender-based violence during the Ebola outbreak in Africa in 2014-16.[37] These reports of gender-based violence are easily deprioritised, unrecognised and under-funded; it is a pattern that is not singular to one country or region.[38]

In the past two years, pandemic-induced lockdowns and their social and economic consequences have increased the exposure of women to abusive partners and other known risk factors while limiting their access to services.[39] Stress, the disruption of social and protective networks, and decreased access to vital sexual and reproductive health services exacerbated the risk of violence for women.[40] It was not uncommon for them to not seek help, amidst lacking legislations, inept implementation of policy interventions, and the societal shame associated with gender-based violence. As the health crisis progressed, the lack of mobility, fear of infection and social interactions, further deterred reporting of such cases.

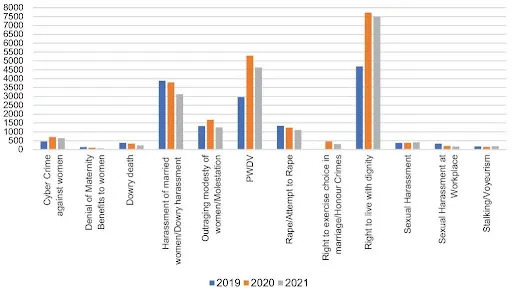

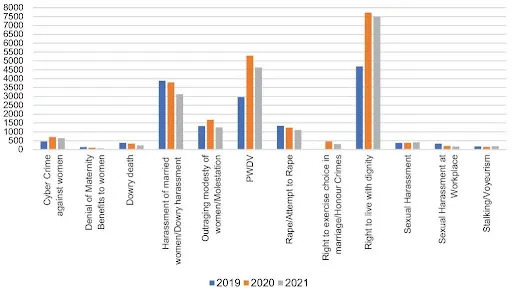

Figure 3 shows a visible increase in some common forms of gender-based violence legally recognised in India, between 2019 and 2021. The National Commission for Women (NCW) registers complaints from women in such distress and seeks to resolve them without actively engaging with the courts. The cases that have particularly seen a rise include domestic violence (as defined under the PWDV Act); dowry harassment; and violations of right to live with dignity. It is important to note here that all of these cases are associated with the presumed “safe” space of a household.

Figure 3: Trend Analysis of GBV complaints registered by NCW (2019-2021)

Source: National Commission for Women (as of September 2021)[41]

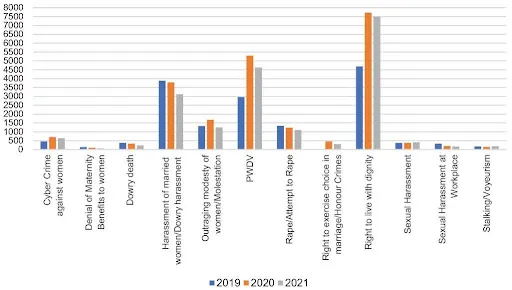

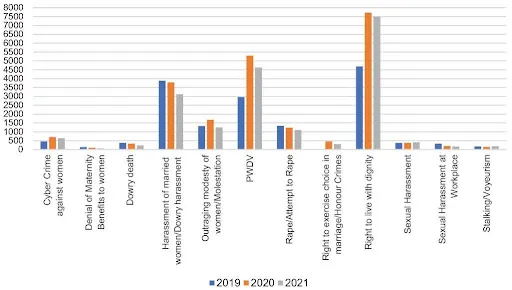

During the past two years, complaints to authorities seeking civil, out-of-court resolutions appear to have increased significantly; at the same time, First Information Reports (FIRs), registered with the Police and required to initiate legal proceedings, saw a bigger decrease. Across the majority of India’s states, the registered cases have either remained the same as in 2019 or have fallen (See figure 4)— contrary to the trend seen from the data from NCW and media reports.[42],[43],[44]

Figure 4: Crimes against Women cases as per FIRs registered (2018-2020)

Source: National Crime Records Bureau, 2020[45]

Many analysts, and not just in India, point to the challenges in accurately determining the real incidence of domestic violence because of under-reporting. In more recent years, however, reporting behaviour in India has been encouraged by specific policies such as the centrally sponsored Sakhi scheme, implemented after the Nirbhaya Rape case of 2012.[d],[46] In states like Telangana and Maharashtra, for example, these crisis centres have become the first avenue for women to report their abuse.

The following section of the paper attempts to provide evidence-based policy solutions for interventions in arresting the incidence of domestic violence in India.

Gender Violence and Women’s Health: A Statistical Analysis

Rationale

Studies across countries of differing overall profiles—such as Nicaragua, Bangladesh, India, and the US—report a high incidence of low birth weight in newborn babies and deaths amongst pregnant women who experience domestic violence.[47],[48],[49],[50] In 2005, WHO conducted a multi-country study on domestic violence and women’s health, which showed strong associations between the two.[51] There is also a strong economic case to be made against violence on women. The World Bank, for example, suggests that the cost of violence against women could be as high as 3.7 percent of a country’s GDP.[52]

This paper analyses household-level findings of the National Family Health Survey-4 (2016) and supplements the data with available literature on domestic violence in India. The aim is to understand trends across a woman’s life cycle that impact their sexual and reproductive health and, subsequently, their children’s nutrition. The areas being explored are sexual and reproductive health of women; child health and nutrition; and women’s empowerment and agency. What are the spillover impacts of domestic violence, and the parallel lack of autonomy and economic agency, on the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition? The paper builds a data-informed case for India to inform policy and prevention practices to protect the rights of women and girls to a safe and secure life.

Methodology

The paper will address each of the known outcomes of domestic violence, using suitable statistical tools; it will corroborate findings with current scientific literature on the subject. For the data analysis, the paper uses the household-level findings of the NFH Round 4 surveys. The number of observations in the household-level data has been trimmed accordingly, to suit the purpose of the study, covering only ever-married women between 15-49 years. The NFHS-4 study was chosen for analysis in the report as it provided complete household-level data for all states and UTs. The household-level data from the latest round of NFHS-5 (2019-21) was yet to be released at the time of conducting this analysis.

The analytical framework is based on two distinct equations, investigating the causal relationship between the incidence of gender-based violence across households in India, and three different categories of socio-economic indicators: (1) Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health; (2) Child Health and Nutrition; and (3) Women’s Empowerment and Agency. Table 1 presents a list of indicators corresponding to each category/domain under study.

Table 1: Indicators (by Domain)

Source: Authors’ own

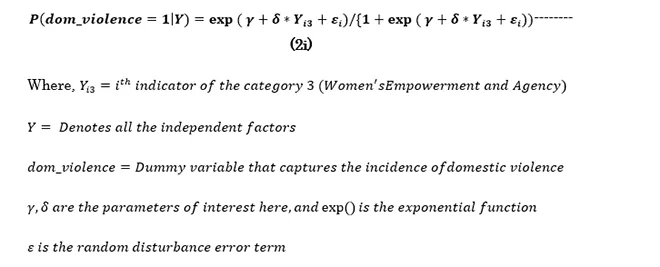

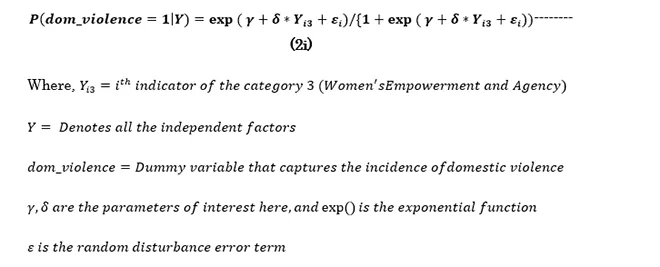

First, the paper explores if domestic violence affects the sexual and reproductive health of women and creates an intergenerational impact upon children’s health and nutrition; if it does, to what extent. Second, it investigates if women having social and economic agency, or not, is a factor in the likelihood of their experiencing domestic violence.

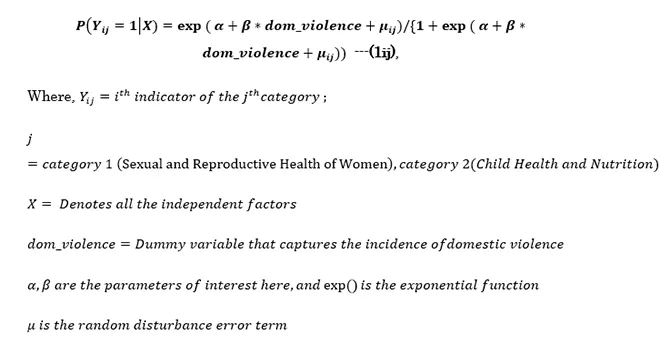

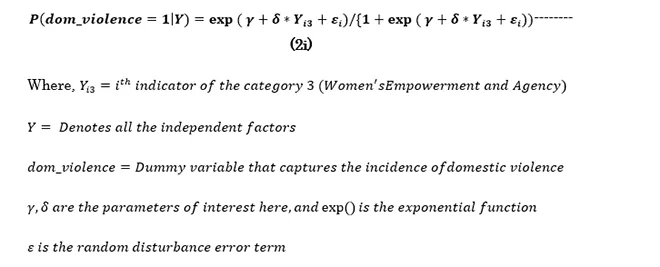

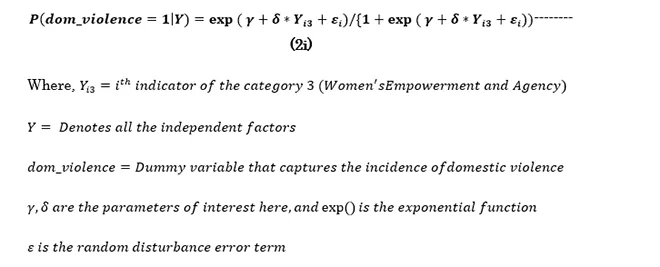

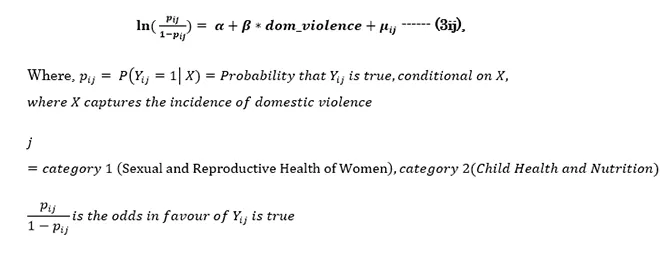

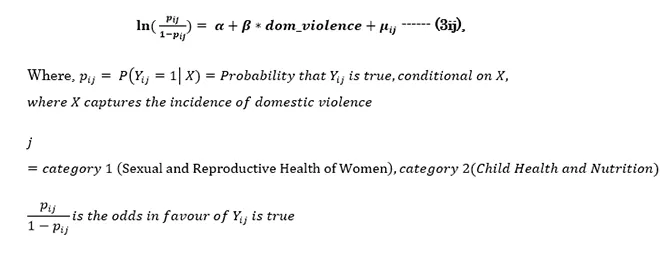

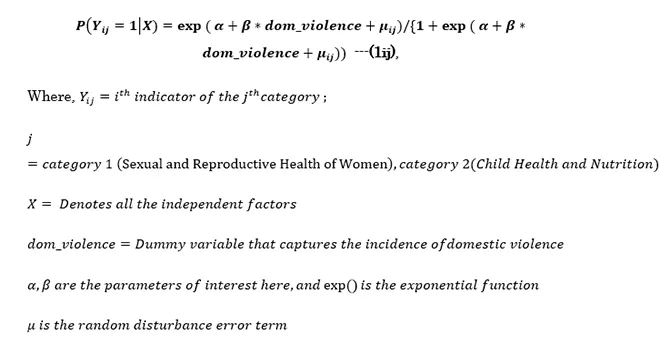

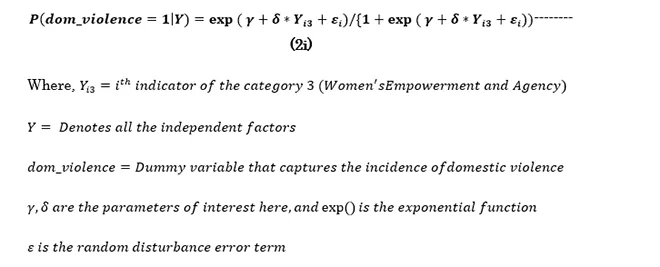

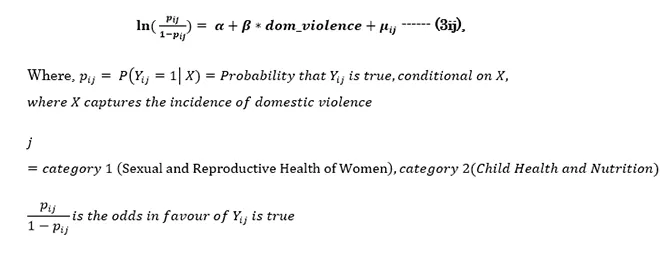

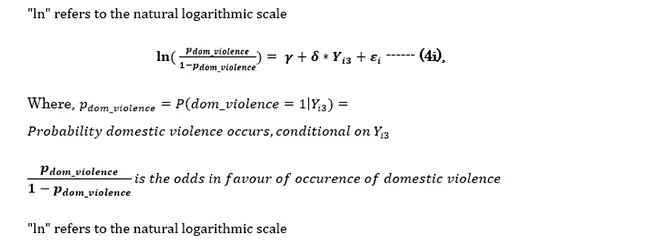

The analysis uses suitable methods of regression analysis. For the first two categories (Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health; and Child Health and Nutrition), the paper explores the causal relationship between incidence of domestic violence and the sexual and reproductive health of women, as well as its intergenerational impact on children’s health and nutrition (as represented by equation [1ij]). For the third category, the direction of causality under investigation is reversed: the analysis explores if, and to what extent, women’s empowerment or the lack of it, affects their vulnerability to domestic violence (as represented by equation [2i]). The two equations shown below capture the conditional probability of an event occurring, based on the independent variables taken under consideration in any specific case.

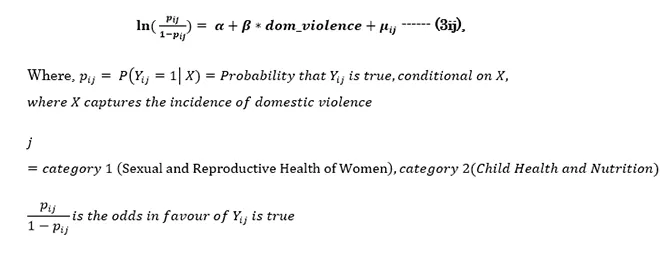

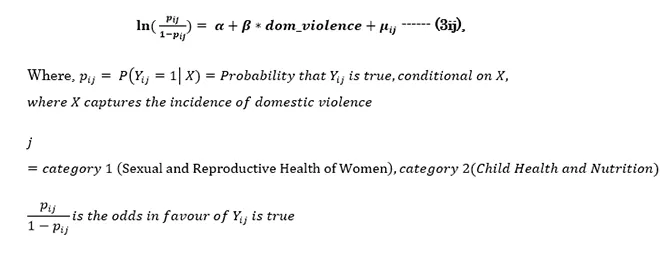

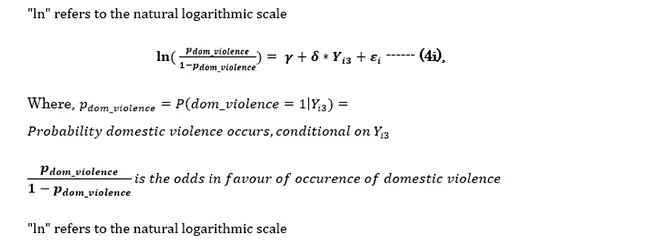

Given that this analysis uses only categorical outcome variables[e] from the household-level survey, it considers a logistic regression model to estimate the above equations and finally obtain the odds-ratio (for two possible outcomes) or relative risk ratio (for more than two possible outcomes), for an easier interpretation.[f] A general form of this logistic transformation of equations (1ij) and (2i) are given below as represented by equations (3ij) and (4i):

Given that this analysis uses only categorical outcome variables[e] from the household-level survey, it considers a logistic regression model to estimate the above equations and finally obtain the odds-ratio (for two possible outcomes) or relative risk ratio (for more than two possible outcomes), for an easier interpretation.[f] A general form of this logistic transformation of equations (1ij) and (2i) are given below as represented by equations (3ij) and (4i):

Given that this analysis uses only categorical outcome variables[e] from the household-level survey, it considers a logistic regression model to estimate the above equations and finally obtain the odds-ratio (for two possible outcomes) or relative risk ratio (for more than two possible outcomes), for an easier interpretation.[f] A general form of this logistic transformation of equations (1ij) and (2i) are given below as represented by equations (3ij) and (4i):

Given that this analysis uses only categorical outcome variables[e] from the household-level survey, it considers a logistic regression model to estimate the above equations and finally obtain the odds-ratio (for two possible outcomes) or relative risk ratio (for more than two possible outcomes), for an easier interpretation.[f] A general form of this logistic transformation of equations (1ij) and (2i) are given below as represented by equations (3ij) and (4i):

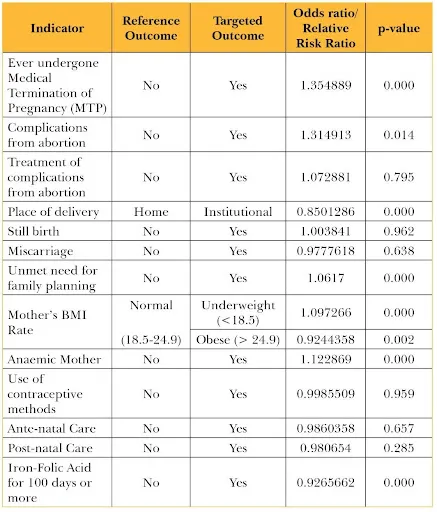

The results of the regression analyses are summarised in the Appendix.[g] The paper is primarily interested in the statistical significance of the odds ratio/relative risk ratio of the independent variables obtained in each case.[h] The odds ratio or relative risk ratio directly measures the strength of the association between the outcome and exposure variables. If the ratio is greater than one (and statistically significant), it indicates that the targeted outcome is more likely to occur than the reference outcome due to exposure, while a ratio less than one (and statistically significant) indicates that the exposure is likely to reduce the chances of occurrence of targeted outcome compared to the reference outcome. The following section discusses the results in detail, and describes corroborating evidence from existing literature.

Summary of Results[i]

Findings from NFHS-4 show that a notable proportion of ever-married women in India report experiencing some form of violence in their intimate relationships, or within the household. The most prevalent forms of abuse are verbal, mental, physical, economic, and sexual.

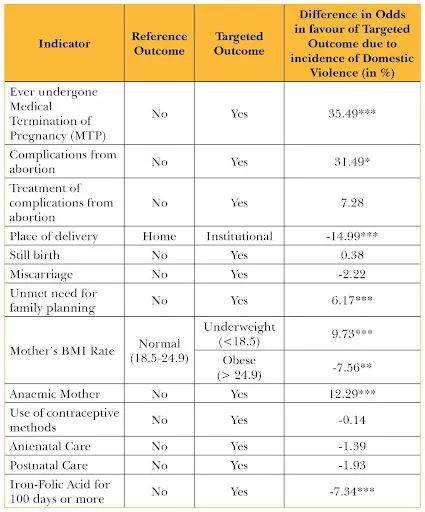

Using the NFHS-4 household survey, we have obtained the difference in the likelihood (statistically speaking, the odds)[j] of the prevalence of inadequate sexual and reproductive healthcare among women and low levels of nutrition and care among their children due to incidences of domestic violence. Corresponding to each indicator, a base-line case (referred to as the reference outcome) has been identified. Against this base-line case, the difference in the likelihood of a specific outcome (i.e., the targeted outcome) among women/mothers who experience domestic violence, compared to those who are not, is analysed. In a broader sense, the results are indicative that the incidence of domestic violence has a significant effect on several indicators of women’s and children’s health, care, and nutrition. Similarly, it is observed that indicators of women’s empowerment and agency significantly affect the odds of them experiencing domestic violence. Here again, the differences in odds corresponding to the base-line case (i.e., reference exposure) and each specific case (i.e., the targeted exposure) has been analysed. However, the nature of relationships obtained in this case is relatively more complex compared to the previous two cases.

Discussion

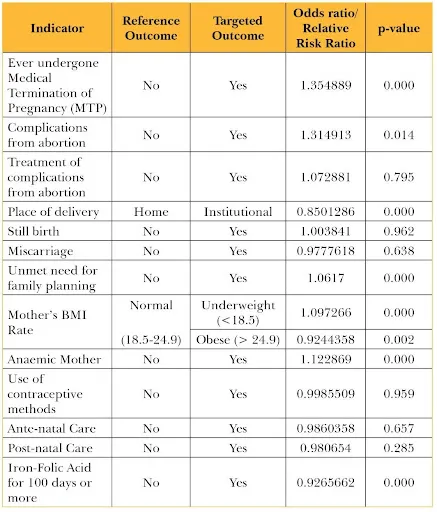

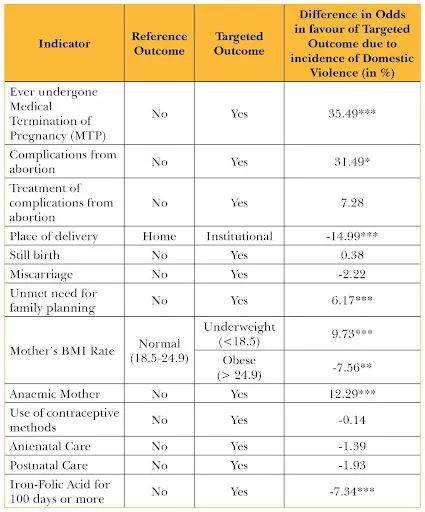

The results obtained for sexual and reproductive health indicators are summarised in Table 2. They show that women in India who experience domestic violence have 35.5-percent higher (statistically significant) odds of undergoing a medical termination of pregnancy. These abortions are likely to result in severe complications.

Similar findings exist in current literature: that violence often acts as a catalyst for women to decide to terminate their pregnancy. Evidence specific to rural India suggests that domestic violence increases the chances of pregnant women opting for induced abortions and later reporting subsequent violence they suffer, and vice versa.[53] It was also found that women with higher socio-economic status and education are also more likely to decide to undergo an abortion, if needed.[54]

But while there is an association in choosing to medically terminate a pregnancy and domestic violence, there is none for pregnancy outcomes and complications experienced. The NFHS-4 sample studied for this paper, showed contradicting results compared to the existing literature. There is no significant association between the incidence of domestic violence, and the indicators of reproductive health such as stillbirth, miscarriages or, in fact, reproductive care such as opting for treatment in case of post-abortion complications, ante-natal or post-natal care, or even use of methods of contraception.

Violence during pregnancy is known to cause adverse health outcomes on the growing foetus, such as the risk of pre-term birth and low birth weight due to the direct trauma or abuse and the physiological effects of stress on foetal growth and development.[55],[56]Studies show a significant association of inadequate gestational weight gain among women experiencing partner violence compared to women reporting no partner violence in pregnancy.[57],[58] Low-income households in Maharashtra and Bihar also experience a high incidence of pre-term labour and pregnancy complications like bleeding, convulsions, and swelling due to spousal violence.[59],[60]

The pattern is not unique to India. In Timor-Leste, women who faced combined forms of violence were twice as likely to terminate their pregnancy.[61] In Iran, intimate-partner violence was associated with adverse maternal outcomes, including pre-term labour, antenatal hospitalisation, and vaginal bleeding.[62] Other adverse effects include: vaginal and cervical infection, kidney infections, bleeding during pregnancy, pre-term labour, severe vomiting, severe post-partum depression, breastfeeding difficulties, lower self-esteem, poor weight gain, and anaemia; cases of maternal death are also reported.

The findings also indicate that women who face any form of abuse at home are 15-percent less likely to give birth in an institutional setup and more likely to deliver at home. (The converse is that deliveries in hospitals, and before that, regular antenatal care visits, are known characteristics of the absence of violence in the household.) The place of delivery has shown in other contexts as well, an influential association with domestic violence. Home deliveries are more common in households with higher prevalence of domestic violence. It has been seen that women facing combined forms of violence complete only three antenatal visits, compared to the four required. Pregnant women with no such stress from violence complete the adequate four visits. Studies from eastern Africa note that receiving professional or institutional assistance during delivery is associated with lesser incidence of IPV.[63]

Rural Uttar Pradesh shows similar behaviour where the prevalence of violence before or during pregnancy resulted in unhealthy reproductive or pregnancy behaviour, poor post-natal care, and limited spousal communication on future family planning.[64] Similar results were observed in Maharashtra, where a new participant, mother-in-law, played a significant role in actively blocking access to health services for their daughter-in-law. In-laws violence showed reduced likelihood for first trimester ante-natal visits.[65]

Our sample further found that women who experience domestic violence are about 6-percent more likely (statistically significant) to have unmet needs for family planning. Literature from other low and lower-middle-income countries corroborates this finding while also suggesting the prominent use of traditional methods to avoid pregnancies.[66]

Body Mass Index (BMI), a vital health indicator for women’s health, remains extremely crucial through the process of pregnancy as well. The analysis revealed that compared to a normal body mass index (18.5-24.9 kg/m2), battered women have 9.73-percent higher chances of being underweight.

Moreover, they also have a 12.3-percent higher odds of being anaemic, and are 7.35-percent less likely to have access to iron supplements to recover from this condition. More so, distress from violence can result in significant complications during pregnancy and childbirth. The risks of stillbirth and miscarriage are also elevated with increased domestic violence. This was also noted in Ethiopia, which found three times higher probability when they experienced intimate partner violence during pregnancy.[67]

Table 2: Causal relationship between Domestic Violence and Sexual & Reproductive Health indicators

Source: Authors’ own

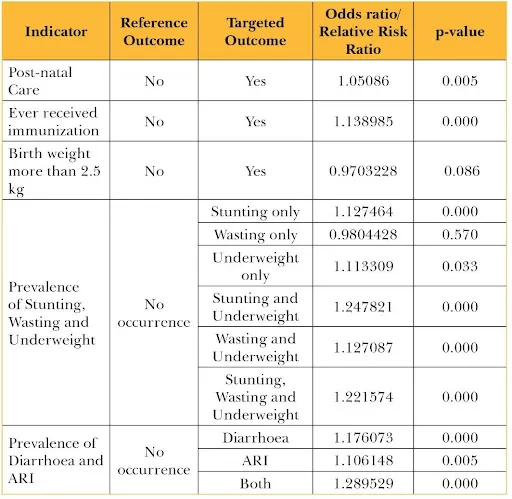

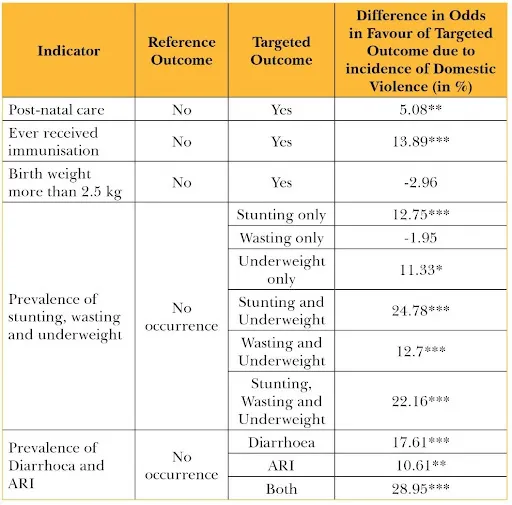

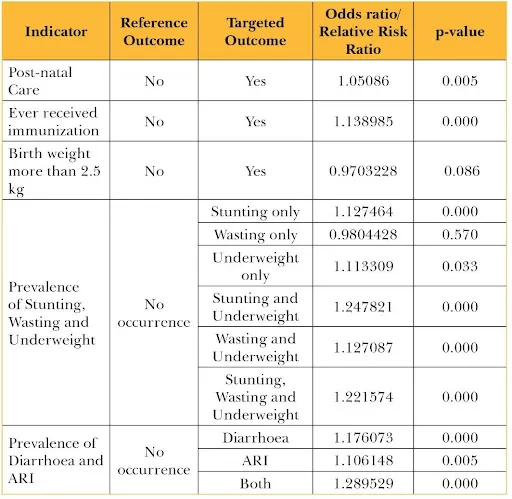

2. Child Health and Nutrition

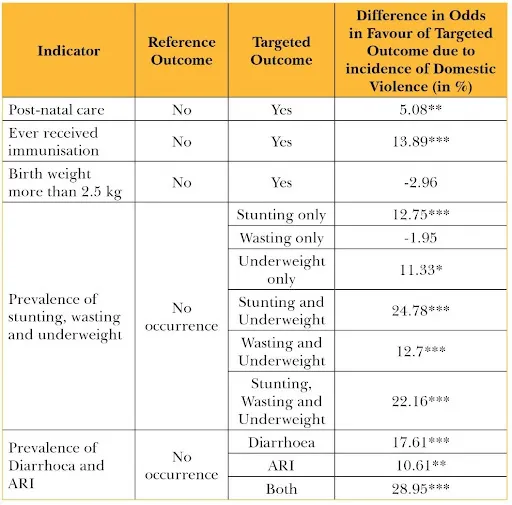

The results obtained for indicators on child’s health and nutrition are summarised in Table 3. There is a positive association between post-natal care and child immunisation and exposure to domestic violence: i.e., mothers who experience abuse are likely to be more vigilant of their child’s care and immunisation. Another 2021 study which studied the same dataset further found that the type of violence experienced by mothers also influences this association. It was noted that emotional violence experienced by mothers in intimate relationships may particularly negatively affect the childhood vaccination coverage.[68]

At the same time, there is no significant association between domestic violence and the child’s birth weight being less than the normal average. Meanwhile, the experience of spousal abuse has a significant association with the child’s long-term nutritional morbidities, growth, and susceptibility to high-risk conditions such as diarrhoea and ARI. (It is important to note here that diarrhoeal diseases and respiratory infections are among the top five leading causes of mortality among under-five children in India.[69]) According to the Global Burden of Disease study (2019), Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Assam have the highest rates of mortality among under-5 children in India.

The likelihood of the child being underweight, wasted, stunted (or any combination of the three conditions) is higher among children whose mothers experience domestic violence. Additionally, coupled with malnutrition, the likelihood of children’s stunting and underweight increases several folds..[70] Higher education of the mother, intended conception of the child, and adequate gap between births are known to help reduce the chances of stunting, as suggested by findings from poor households in Mumbai, India.[71]

With reference to normal nutritional growth, a child whose mother suffers domestic violence is 24.78-percent more likely (statistically significant) to be both stunted and underweight; followed by a 22.16-percent higher odds (statistically significant) of the child being stunted, wasted as well as underweight compared to children whose mothers have a healthy intimate relationship.

Similarly, such children also have an almost 29-percent higher odds (statistically significant) of experiencing both diarrhoea and ARI.

Table 3: Causal relationship between Domestic Violence and Child Health & Nutrition indicators

Source: Authors’ own

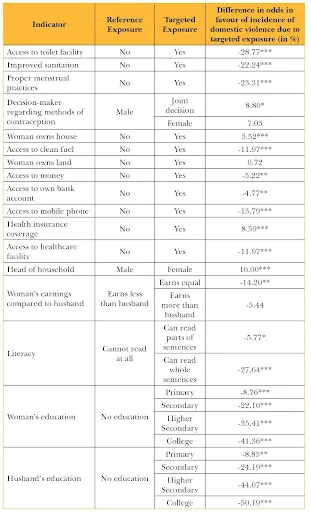

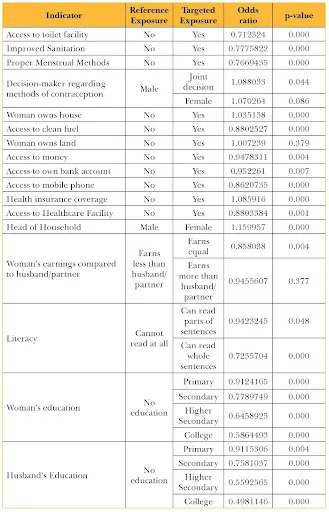

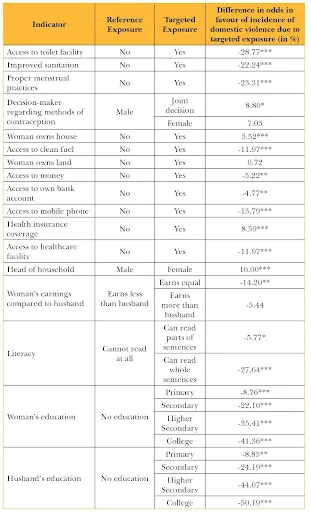

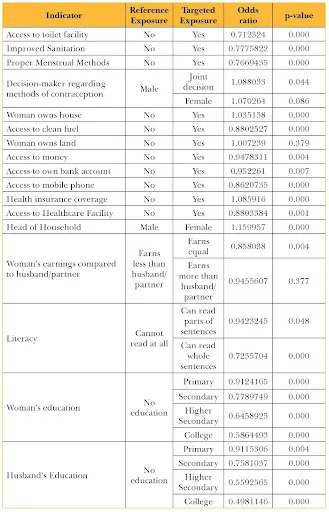

3. Women’s Empowerment and Agency

The results obtained for women’s empowerment and economic or social agency indicators are summarised in Table 4. Several indicators of access are used: proper toilet facility, improved sanitation, menstrual practices, healthcare facilities, income, own bank account, mobile phone, and health insurance. Measures such as use of clean fuel and access to healthcare allow safer ways to perform household duties and thereby indicating dignity. The sense of empowerment is continued in interactions with support networks and access to knowledge as offered, for instance, by mobile phones and bank accounts. The odds of women being subjected to domestic violence are significantly lower among households where women have access to toilet facilities, improved sanitation, and proper menstrual practices, clean fuel, and, also, institutional healthcare. Homes with lesser incidence of violence are also households predominantly using improved sanitation facilities with modern toilets.

Table 4: Causal relationship between Domestic Violence and Women’s Empowerment & Agency

Source: Authors’ own

Studies have also found that ownership of assets and agency significantly reduce women’s vulnerability to sexual and physical violence, although not of the verbal kind.[72] Evidence shows that cash-transfer programs can reduce domestic violence by improving economic security and emotional well-being, and can nurture empowerment.[73] A Bangladesh study indicates cash transfers, along with changes in communicating proper nutrition behaviour can significantly lessen domestic violence.[74]

The nature of control and subjugation of women varies across societies and differs on grounds of class, caste, religion, region, and ethnicity. Some studies have found other variables of privilege—including participation in household decisions, working and earning their own income—that have a positive association with violence in household: i.e., a woman who earns her own income is less likely to experience violence.[75] An interesting trend is seen in the matter of incomes. Women who earn equal to their husbands have about 14-percent lower odds (statistically significant) of being victims of domestic violence as compared to women who earn less than their husbands. In contrast, for women who earn more than their husband or women whose husbands do not earn anything at all, this difference in odds is significantly lower and not even statistically significant. Only in circumstances where spousal earnings are equal in terms of their contribution to the household, is where it acts as a deterrent to violence.[76],[77]

Indicators of women’s individual economic agency and empowerment have significant association with the prevalence of domestic violence: access to own bank account and mobile phone, owning their house and control over money, and participation in decision-making roles regarding methods of contraception or as head of households. Existing literature from 20 countries shows that when a household is better-equipped in information and communication technology tools such as radio, television, computer and smartphones, women are less likely to experience battery.[78] Similar evidence is found in India: in Bihar, access to mobile phones is found to encourage women to seek social support and access necessary information, thereby helping decrease spousal violence.[79]

In this present study, the results indicate that women who have access to mobile phones are in a better position and about 13.79-percent less likely (statistically significant) to suffer domestic abuse. The introduction of technology has facilitated a breaking-away from traditional gender roles. This is therefore a crucial new element to be considered when introducing behavioural change interventions in society. Despite the rampant digital divide in India, mobile phones and the internet are assets that can be nothing less than revolutionary for women who are combatting abuse.

To be sure, the empowerment for women cannot be measured without contextualising factors such as mobility, control over resources, bodily autonomy, nutrition needs, and more. In terms of land ownership, studies in both patrilineal and matrilineal societies of Telangana, Karnataka, Haryana, and Meghalaya found almost 95 percent of the surveyed women asserting that if they have land and assets ownership to their name, they will be safer from violence of all kinds. They will likely have improved autonomy in terms of birth control, family size, children’s health and nutrition, have better access to financial gains and healthcare, and feel more secure to take the risk of leaving abusive relationships.[80] Women with access to bank accounts and control over money have significantly lower odds (4.77 percent and 5.22 percent, respectively) of experiencing domestic violence.

There is indicative and statistically significant evidence that women’s participation in decision-making significantly increases their vulnerability to domestic violence. Women in households where they have a voice in decisions regarding contraception methods have higher odds of suffering domestic violence—this could indicate that the “empowerment” is still to grow roots, and there is much scope for progress. More significantly, women in female-headed households[k] face 16-percent higher odds of facing domestic abuse.

Literacy and levels of education attained by both women and men also have a significant impact on reducing the incidence of domestic violence. For each subsequent increase in levels of literacy and education, the likelihood of women experiencing abuse comes down, as compared to those with no literacy or education (reference group). Other earlier studies conducted in different countries have found that women having access to schooling and education are less likely to experience abuse.[81],[82]

The difference in odds for each level (in comparison to the reference group) is represented in Table 1-4 (along with their statistical significance). For the highest levels of education (i.e., college), the odds of women experiencing abuse are as much as 41.36 percent lower for college-educated women, and 50.19-percent lower when the husband is college-educated. On an important line, while literacy and higher levels of education among women have historically helped reduce the prevalence of domestic violence, spousal education showed a similar trend. Husbands with higher levels of education are less likely to engage in violence. Evidence from other countries indicates a lower incidence of domestic abuse in couples where the woman is more educated than the husband or partner, compared to equally low-educated spouses.[83]

According to the results of our present analysis, improvements in men’s education levels have a more substantial positive impact on reducing the incidence of domestic violence, as compared to progress in the women’s education levels and literacy.

These findings are true across several studies reported across Asia and Latin America, and there are several factors at play. It is important to note that women’s experience of violence in the household is usually in line with their degree of disadvantaged position within a patriarchal social system. Women armed with familial support, education, and asset or land ownership enjoy greater autonomy and freedoms and are more resilient to repressive gender norms. In isolation, these indicators of land or house ownership, control over money, and similar financial assets may not make a significant change in women’s sense of empowerment and on the contrary could make them targets of greater threat.[84] The rise of women’s economic independence is seen as a threat to men’s dominant roles as provider and protector.[85]

Recommendations and Conclusion

Women who experience domestic violence continue to carry a stigma in countries such as India where significant parts remain enmeshed in patriarchy. Therefore, women’s susceptibility to violence is merely a result of a conflagration of variables that characterise their communities. The imperative is for India to address domestic violence on a clear, targeted policy level: such acts of violence are clear violations of human rights and they have massive impacts on public health, in turn hindering genuine, inclusive, and sustainable development.

The lifecycle approach utilised in this present study emphasises that the prevalence of domestic violence affects women’s sexual and reproductive health and health outcomes, and has social and economic consequences and costs for families, communities, and societies. The study recommends the following for ensuring women’s economic agency, which in turn can allow them the full utilisation of their sexual and reproductive rights:

- Attitudes and norms that accept violence as an “expected” part of spousal life and recognising it only as a “personal” event trivialise its political and economic consequences. Domestic violence cases go unnoticed as women are usually discouraged from seeking any type of relief services or legal interventions. It is a preventable concern that calls for mitigating the risks and amplifying protection.

- Domestic violence is not merely a legal and policy challenge but a public health concern as well. It impacts mothers’ health and consequently that of their children, thereby perpetuating inter-generational, avoidable morbidities. Socio-legal and health systems need to be integrated in an age- and gender-positive manner to improve accessibility for all.

- Strengthen the enabling environment by enforcing laws and policies that address violence against women. It is important to note that intersectionalities of caste-class-religion are crucial determinants of how women deal with circumstances of violence. Government initiatives like Sakhi centres and Swadhaar homes provide help, but they should be made uniformly available across the country.

- Empowerment can only be brought about by a holistic awareness-raising. Low education in India places women at unequal power positions in intimate relationships. Gender equality can be promoted by enhancing continued access to secondary education, digital tools and designing women-centric legal reforms. A critical balance of education, health, employability and decision-making power will be key in giving women in India a more secure life.

Appendix

Regression Results (Domain-Wise)

- Sexual and Reproductive Health of Women

2. Child Health and Nutrition

3. Women’s Empowerment and Agency

Endnotes

[a] The 1993 United Nations Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women defines ‘gender-based violence’ as “an act that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering to women (including threats of such acts), or coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life.” The focus of this paper is Domestic Violence—the most common form of GBV against women.

[b] This paper defines ‘domestic violence’ as any form of violence (physical, sexual, psychological and verbal) against women in a domestic setting of a marital home or, within an intimate relationship, that results in or is likely to result in physical or mental harm or suffering to, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life. It is often used interchangeably with intimate partner violence.

.[c] This is according to literature from the World Health Organization (WHO).

[d] In 2012, Jyoti Singh, a 22-year-old physiotherapy intern was raped and viciously assaulted by six men; she would eventually succumb to her severe injuries. Delhi’s ‘Nirbhaya’ movement (Jyoti was first named ‘Nirbhaya’ by the media) became pivotal to the battle to arrest the high incidence of violence against women in India.

[e] Simple linear regression models cannot be used to analyse non-continuous, discrete outcomes. Therefore, logit regression models have been used which use a maximum likehood function to estimate the odds in favour of target outcome against a reference outcome due to variations in the independent variables.

[f] Both classes of logistic regression models, used here, include only one categorical independent variable in each case. This essentially makes the analysis similar to the mean-sample proportions test. However, a statistically significant regression analysis helps us to establish a causal relationship, besides also providing us a measure of the difference in sample proportions as compared to the simpler mean-sample proportions testing method of analysis.

[g]All computations have been done on STATA 14.0.

[h] The odds ratio or the relative risk ratio, corresponding to particular independent variable is obtained as follows:

In the above mentioned cases,

[i] The statistical significance of the results obtained are indicated as follows:

* : Significant at 5% level of significance

** : Significant at 1% level of significance

*** : Significant at 0.1% level of significance

[j]The difference in odds/relative risk is calculated as:

[k] Household in which an adult female is the sole or main income producer and decision-maker

[1] World Health Organization. “Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women.” (2021).https://www.who.int/news/item/09-03-2021-devastatingly-pervasive-1-in-3-women-globally-experience-violence

[2] Declaration, Beijing. “Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action Fourth World Conference on Women.” Paragraph 112 (1995),

https://www.un.org/en/events/pastevents/pdfs/Beijing_Declaration_and_Platform_for_Action.pdf

[3] Assembly, General. “Sustainable development goals.” SDGs Transform Our World 2030 (2015).https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

[4] World Health Organization. “Global plan of action to strengthen the role of the health system within a national multisectoral response to address interpersonal violence, in particular against women and girls, and against children.” (2016).https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/global-plan-of-action/en/

[5] Women, U. N. “Turning promises into action.” Gender equality in the 2030 (2018).

[6]World Health Organization. Violence against women. No. WHO/FRH/WHD/97.8. World Health Organization, 1997.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

[7]World Health Organization. “Devastatingly pervasive: 1 in 3 women globally experience violence.” New York (2021).https://www.who.int/news/item/09-03-2021-devastatingly-pervasive-1-in-3-women-globally-experience-violence

[8]Stöckl Heidi et al., “The global prevalence of intimate partner homicide: A systematic review.” The Lancet 382, no. 9895 (2013): 859-865. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(13)61030-2/fulltext

[9]Stripe, Nick. “Domestic abuse during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, England and Wales: November 2020.” Office for National Statistics 25 (2020). https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabuseprevalenceandtrendsenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2020

[10]Morgan RE et al., “Criminal victimization, 2018.” Bureau of Justice Statistics 845 (2019).https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv18.pdf

[11] International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. 2017. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India. Mumbai: IIPS. http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-4Reports/India.pdf

[12]Grose RG et al., “Sexual and reproductive health outcomes of violence against women and girls in lower-income countries: a review of reviews.” The Journal of Sex Research 58, no. 1 (2021): 1-20.https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00224499.2019.1707466

[13]UN Women, Consequences and Costs (2010),

https://www.endvawnow.org/en/articles/301-consequences-and-costs-.html

[14] Sakti Golder, Measurement of Domestic Violence in NFHS Surveys and Some Evidence, Oxfam India (2018),

[15]Kimuna, Sitawa R., Yanyi K. Djamba, Gabriele Ciciurkaite, and Suvarna Cherukuri. “Domestic violence in India: Insights from the 2005-2006 national family health survey.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 28, no. 4 (2013): 773-807.

[16]Anand E et al., “Intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy among adolescent and young adult married women in south Asia.” Journal of biosocial science 49, no. 2 (2017): 206-221.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932016000286

[17]Beydoun HA et al., “Intimate partner violence against adult women and its association with major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms and postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Social science & medicine 75, no. 6 (2012): 959-975.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22694991/

[18]Sarkar, N. N. “The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcome.” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 28, no. 3 (2008): 266-271. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18569465/

[19]Sigalla GN et al., “Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and its association with preterm birth and low birth weight in Tanzania: A prospective cohort study.” PloS one 12, no. 2 (2017):

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0172540

[20]Raj A et al., “South Asian victims of intimate partner violence more likely than non-victims to report sexual health concerns.” Journal of Immigrant Health 7, no. 2 (2005): 85-91.

[21]Normann AK et al., “Intimate partner violence and breastfeeding: a systematic review.” BMJ open 10, no. 10 (2020): e034153.

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/10/10/e034153#:~:text=Miller%2DGraff%20et%20al20,of%20shortened%20duration%20of%20breastfeeding

[22]Jannatul Ferods and Md Mosfequr Rahman, “Exposure to intimate partner violence and malnutrition among young adult Bangladeshi women: cross-sectional study of a nationally representative sample,” Cadernos de SaudePublicia 34(7), (2018), https://www.scielo.br/j/csp/a/7mwjGXwYDsQXDBbQPbRkknn/?lang=en

[23]Ramesh P Adhikari et al., “Intimate partner violence and nutritional status among Nepalese women: An investigation of associations,” BMC Women’s Health 20, no. 27 (2020), https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-020-00991-x

[24]Shireen Ziaei et al., “Women’s exposure to intimate partner violence and child malnutrition: Findings from demographic and health surveys in Bangladesh,” Maternal and Child Nutrition (2014), 10, pp. 347–359 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00432.x

[25]S.V. Subramanian et al., “Domestic Violence and Chronic Malnutrition among Women and Children in India,” American Journal of Epidemiology, 170 (268), (2008), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21492979/

[26]Natasha Shaukat et al., “Detrimental effects of intimate partner violence on the nutritional status of children: Insights from PDHS 2012-2013,” International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health vol 5 no.5 (2018), https://www.ijcmph.com/index.php/ijcmph/article/view/2395

[27]Pakrashi D, Saha S. “Intergenerational consequences of maternaldomestic violence: Effect on nutritional status ofchildren”, (2020)

https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/217489/1/GLO-DP-0551.pdf

[28] Sinha A, Chattopadhyay A (2017) “Inter-Linkages between Spousal Violence and Nutritional Status of Children: A Comparative Study of North and South Indian States”. Social Crimonol 5: 171

[29] Sinha A, Chattopadhyay A (2017) “Inter-Linkages between Spousal Violence and Nutritional Status of Children: A Comparative Study of North and South Indian States”. Social Crimonol 5: 171.

[30] Dowry Prohibition Act 1961, Ministry of Women & Child Development, https://wcd.nic.in/act/dowry-prohibition-act-1961

[31]Ministry of Health and Family, Welfare National Family Health Survey 4, State Fact Sheet (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare 2014-15),http://rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_nfhs-4.shtml

[32]Government of India, Section 498A. Husband or relative of husband of a woman subjecting her to cruelty, India Code , Digital Repository of all Central and State Acts.

[33]Government of India, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, India Code (2005)

[34]Nata Duvvury, compiled, Domestic Violence in India: A Summary Report of Three Studies (1999) International Center for Research on Women and The Centre for Development and Population Activities.

[35] “Violence against women prevalence estimates 2018”, World Health Organization, Geneva (2021), Violence against women prevalence estimates 2018.

[36]United Nations (2019). https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/E_Infographic_05.pdf

[37]Neetu John, et all, “Lessons Never Learned: Crisis and gender‐based violence”, Developing world bioethics, 20(2), 65-68, (2020).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7262171/

[38]Neetu John, et all, “Lessons Never Learned: Crisis and gender‐based violence”, Developing world bioethics, 20(2), 65-68, (2020).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7262171/

[39]Violence against women, World Health Organization, 2021, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

[40]“COVID-19 and violence against women”, World Health Organization, 2020, https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1274324/retrieve

[41]National Commission for Women, http://ncwapps.nic.in/frmReportNature.aspx?Year=2020

[42] Payal Seth, “As COVID-19 Raged, the Shadow Pandemic of Domestic Violence Swept Across the Globe”, The Wire, 23 January 2021, https://thewire.in/women/covid-19-domestic-violence-hdr-2020

[43] Vasundharaa Nair et. al., ““Crisis Within the Walls”: Rise of Intimate Partner Violence During the Pandemic, Indian Perspectives”, Frontier, 28 May 2021, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgwh.2021.614310/full

[44] Vighnesh Radhakrishnan et. all., “Domestic violence complaints at a 10-year high during COVID-19 lockdown”, The Hindu, June 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/data/data-domestic-violence-complaints-at-a-10-year-high-during-covid-19-lockdown/article31885001.ece

[45]National Crime Records Bureau, 2020, https://ncrb.gov.in/en/Crime-in-India-2020

[46]Sakhi – One Stop Centre Scheme, Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2017,

[47]Valladares Eliette et al., “Physical partner abuse during pregnancy: a risk factor for low birth weight in Nicaragua.” Obstetrics & Gynecology 100, no. 4 (2002): 700-705.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0029784402020938

[48]Fauveau Vincent et al., “Causes of maternal mortality in rural Bangladesh, 1976-85.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 66, no. 5 (1988): 643.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc2491193/

[49]Ganatra BR et al., “Too far, too little, too late: a community-based case-control study of maternal mortality in rural west Maharashtra, India.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 76, no. 6 (1998): 591.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2312494/

[50]Martin SL et al., “Pregnancy-associated violent deaths: the role of intimate partner violence.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 8, no. 2 (2007): 135-148.https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1524838007301223

[51]WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: summary report of initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2005. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43310/9241593512_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[52]World Bank ‘Gender based violence (violence against women and girls)’ 2019. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/socialsustainability/brief/violence-against-women-and-girls

[53]Rob Stephenson, et al., “Domestic Violence and Abortion Among Rural Women in Four Indian States,” Violence against women, 22(13), (2016),

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1077801216630148

[54] Anju Malhotra et. al., “Realizing Reproductive Choice and Rights: Abortion and Contraception in India” International Centre for Research on Women, 2016.

[55]Jeanne Chai et al., “Association between intimate partner violence and poor child growth: results from 42 demographic and health surveys.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 94, no. 5 (2016): 331.

[56]Eskedar Berhanie et al., “Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a case-control study.” Reproductive Health 16, 22 (2019).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0670-4

[57]Jeanne L. Alhusen et. al., “Intimate Partner Violence and Gestational Weight Gain in a Population-Based Sample of Perinatal Women.” Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing : JOGNN vol. 46,3 (2017): 390-402.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2016.12.003

[58]C. L. Moraes et al., “Gestational weight gain differentials in the presence of intimate partner violence.” International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics vol. 95,3 (2006): 254-60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.08.015

[59]Jay G. Silverman et al., “Maternal morbidity associated with violence and maltreatment from husbands and in-laws: findings from Indian slum communities.” Reproductive Health 13, 109 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0223-z

[60]Diva Dhar et al., “Associations between intimate partner violence and reproductive and maternal health outcomes in Bihar, India: a cross-sectional study.” Reproductive Health 15, 109 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0551-2

[61]Angela J. Taft et al., “The impact of violence against women on reproductive health and child mortality in Timor-Leste.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39(2015): 177-181. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12339

[62]M Hassan et al., “Maternal outcomes of intimate partner violence during pregnancy: study in Iran.” Public health vol. 128,5 (2014): 410-5.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2013.11.007

[63] Peter Memiah et al., “Neonatal, infant, and child mortality among women exposed to intimate partner violence in East Africa: a multi-country analysis.” BMC Women’s Health 20, 10 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0867-2

[64]Jaleel Ahmad et al., “Gender-Based Violence in Rural Uttar Pradesh, India: Prevalence and Association With Reproductive Health Behaviors.” Journal of interpersonal violence vol. 31,19 (2016): 3111-3128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515584341

[65]Jay G. Silverman et al., “Maternal morbidity associated with violence and maltreatment from husbands and in-laws: findings from Indian slum communities.” Reproductive Health 13, 109 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0223-z

[66]Angela J. Taft et al., “The impact of violence against women on reproductive health and child mortality in Timor-Leste.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39(2015): 177-181. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12339

[67]Kahsay Zenebe Gebreslasie et. al., “Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and risk of still birth in hospitals of Tigray region Ethiopia.” Italian Journal of Pediatrics 46, 107 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-020-00857-w

[68] Pintu Paul and Dinabandhu Mondal, “Maternal Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence and Child Immunisation: Insights from a Population-based Study in India”. Journal of Health Management. 1-13.(2021)

[69]“GBD India Compare.” Global Burden of Diseases 2019.

https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/india

[70]Dinabandhu Mondal and Pintu Paul “Association between intimate partner violence and child nutrition in India: Findings from recent National Family Health,” Children and Youth Services Review (2020) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190740920314110

[71] Sushmita Das et. al., “Determinants of stunting among children under 2 years in urban informal settlements in Mumbai, India: evidence from a household census” Journal of Health Population and Nutrition 39, 10 (2020).

[72]Govind Kelkar et al., “Women’s Asset Ownership and Reduction in Gender-based Violence” Heinrich Böll Foundation and Landesa, (2015).

[73]Melissa Hidrbo and Shalini Roy,comment on “Cash transfers and intimate partner violence.” IFPRI Blog: Research Post, posted on April 3, 2019.

[74]Shalini Roy et al., “Transfers, Behavior Change Communication, and Intimate Partner Violence: Post program Evidence from Rural Bangladesh.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 2019; 101 (5): 865–877.

[75] Jaleel Ahmad, Nizamuddin Khan and Arupendra Mozumdar, “Spousal Violence Against Women in India: A Social–Ecological Analysis Using Data From the National Family Health Survey 2015 to 2016”, Journal of Interpersonal Violence (2019).

[76]Anna Aizer, “The Gender Wage Gap and Domestic Violence.” The American economic review vol. 100,4 (2010): 1847-1859.

[77]Maani Truu, “Women are more likely to experience domestic violence when they out-earn their partner.” SBS News, posted on March 30, 2021.

[78]Lauren F. Cardoso and Susan B Sorenson, “Violence Against Women and Household Ownership of Radios, Computers, and Phones in 20 Countries.” American journal of public health vol. 107,7 (2017): 1175-1181.

[79]Diva Dhar et al., “Associations between intimate partner violence and reproductive and maternal health outcomes in Bihar, India: a cross-sectional study.” Reproductive Health 15, 109 (2018).

[80]Govind Kelkar et al., “Women’s Asset Ownership and Reduction in Gender-based Violence.” Heinrich Böll Foundation and Landesa, (2015).

[81]Dirgha J. Ghimire et al., “Impact of the spread of mass education on married women’s experience with domestic violence.” Social science research vol. 54 (2015): 319-31.

[82]Daniel Rapp et al., “Association between gap in spousal education and domestic violence in India and Bangladesh.” BMC Public Health 12, 467 (2012).

[83]Daniel Rapp et al., “Association between gap in spousal education and domestic violence in India and Bangladesh.” BMC Public Health 12, 467 (2012).

[84]Koustuv Dalal, “Does economic empowerment protect women from intimate partner violence?”, Journal of Injury and Violence Research, 3(1), 35-44 (2011).

[85] Jaleel Ahmad, Nizamuddin Khan and Arupendra Mozumdar, “Spousal Violence Against Women in India: A Social–Ecological Analysis Using Data From the National Family Health Survey 2015 to 2016”, Journal of Interpersonal Violence (2019).

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV