Introduction

Pakistan is on the verge of an economic meltdown: people are struggling to cope with ever declining purchasing power, forex reserves are dwindling, and inflation is ‘galloping’; the country is also grappling with increasing civil disobedience and widespread unrest, and tensions are running high as the upcoming polls loom, further fuelling uncertainty. The country is walking a financial, economic, and political tight rope, raising fears of a response in the form of a military crackdown.[1] The situation is threatening to culminate in a humanitarian disaster akin to that which unfolded in Sri Lanka in 2022. Compounding the challenges to the Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s government is the political turmoil stoked by the ouster of the Imran Khan government—the country's first successful no-confidence motion since its independence.[2]

To be sure, the pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions have had disastrous consequences to economies worldwide, and Pakistan is no exception. As 2022 ended, the COVID-19 surge in China—the second largest economy accounting for 18 percent of global GDP, and pivotal to Global Value Chains (GVCs)[3] in South and Southeast Asia—caused spillover impacts on the rest of the world.[4]

On one hand, the South Asian neighbourhood is in flux: Sri Lanka is on the verge of a complete economic collapse, Myanmar witnessed a military coup and the unemployment situation has grown colossal, Bangladesh and India are experiencing inflation and volatility of domestic currency, Nepal is suffering widening trade deficits and declining foreign exchange reserves, and Pakistan is in the midst of political turmoil and financial emergency. At the same time, the Ukraine-Russia conflict has thrown the energy markets into a complete mess in several developing nations, especially Pakistan and Bangladesh. Additionally, supply cuts by edible-oil exporting countries and the impact of energy price rise on food inflation have made food security a massive concern, especially for the financially vulnerable sections of society.

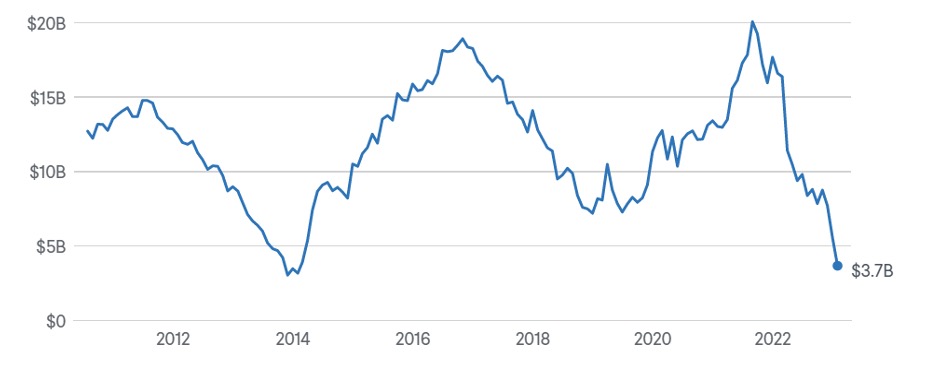

Pakistan's forex reserves have plummeted to a historic low of US$ 3.19 billion by the end of February 2023[5]—just enough to buy the nation two weeks' worth of imports as opposed to the International Monetary Fund (IMF)-mandated three months of cover.[6] This does not help, given that the country has to pay back a huge debt projected to reach US$ 73 billion by 2025.[7]Currently, the country’s US$ 126-billion debt burden is composed mainly of loans from China and Saudi Arabia.[8]

While relations between Pakistan and China seem more robust than ever, one cannot ignore the Sindh and Baloch separatists threatening the security of Chinese nationals working there.[9] On more than one occasion, China has threatened to end its developmental projects in Pakistan under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and proposed hiring Chinese security firms to safeguard its citizens involved in these projects. Allowing Chinese security agencies to operate inside Pakistan would undermine the Pakistan Army's power to defend its foreign nationals. Further, international perceptions of the country being a hotbed of terrorist activity make potential foreign investors and aid providers reticent to engage in Pakistan. Another notable creditor to Pakistan—Saudi Arabia, with which it has geopolitical and religious ties—provides critical investments in the former.[10]

Another issue that Pakistan has been historically grappling with is physical corruption in the form of bribery and embezzlement, and other illicit practices. This has undermined the integrity of public institutions and eroded trust in government, thereby hampering socio-economic progress. The prevalence of corruption has also distorted market mechanisms, perpetuated an unequal distribution of resources, and stifled entrepreneurial activity in Pakistan. It has adversely affected foreign investments into the country and deterred international cooperation, further exacerbating the country's economic woes.[11]

The Pitfalls of Pakistan’s Massive External Debts

Pakistan's ties with its two biggest 'all-weather' allies—China and Saudi Arabia—date back several decades ago. China has had developmental and trading interests in Pakistan since the 1960s, following the Sino-Indian war, when the former extended interest-free credit worth US$ 85 million[a] for technological and infrastructural projects. The two also signed bilateral trade agreements aimed at speeding up industrialisation in Pakistan.[12]

For its part, Saudi Arabia—Pakistan’s most loyal confederate in Islam—has been extending its generosity since 1943 in response to Muhammad Ali Jinnah's call for help, while Pakistan has lent its support to the Saudi Kingdom's military might in the nuclear and arms security front.[13]

Over the decades, Pakistan's diplomatic alliances with both China and Saudi Arabia have evolved in parallel with the churning of the geopolitical landscape and remain a testament to successful international partnerships grounded in mutual interests.

China and Chinese commercial banks hold about 30 percent of Pakistan's total external debt of over US$ 100 billion,[14] a proportion that grossly overshoots the 20-percent share of Chinese loans in Sri Lanka's public external debt.[15] Moreover, the loan disbursal of an additional US$ 700 million that the country received from the China Development Bank (CDB) in early 2023[16] further adds to the crushing weight of external debt commitments due this year.

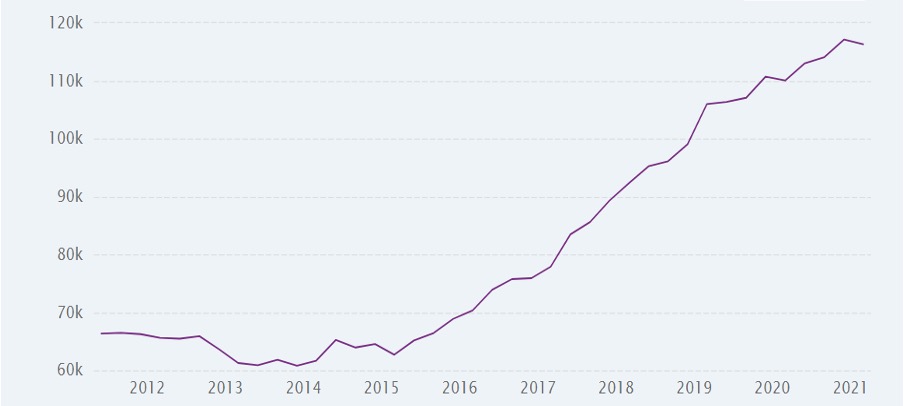

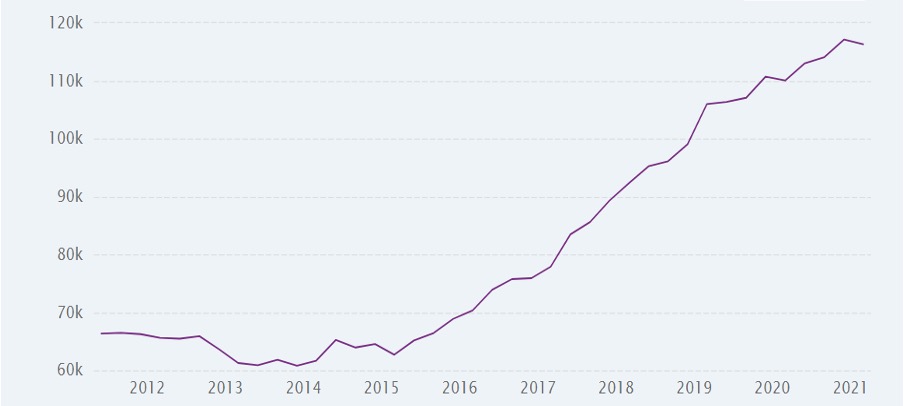

Figure 1: Pakistan's Total External Debt (in US$ million, 2006-2022)

Source: CEIC / State Bank of Pakistan[17]

Pakistan’s Unsustainable Debt

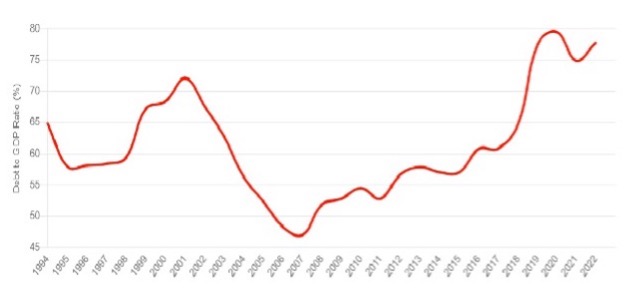

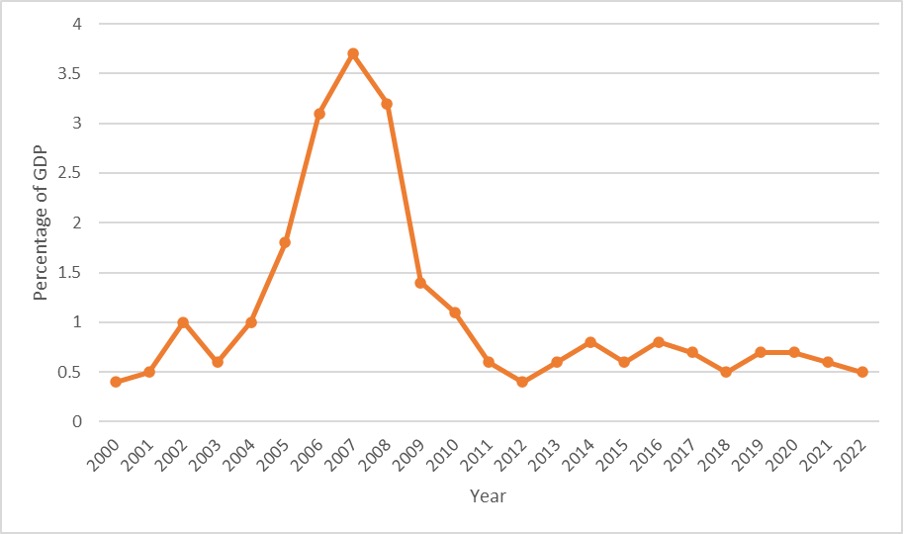

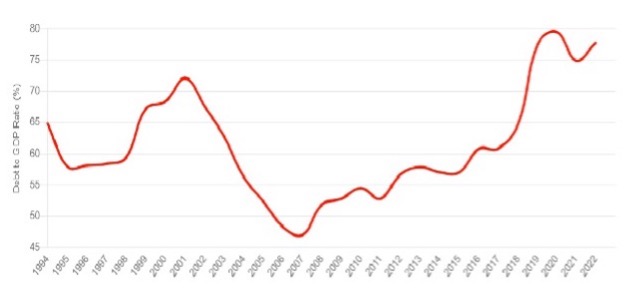

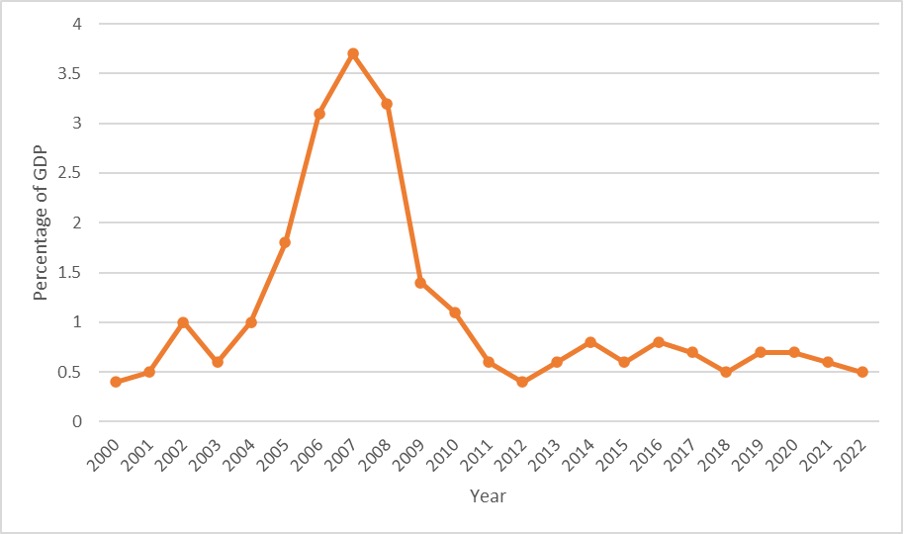

By December 2022, Pakistan’s external debt stood at US$ 126.3 billion,[18] i.e., a massive 33 percent of its GDP. While around 77 percent of this debt, or US$ 97.5 billion, was on the Government itself, the public sector enterprises controlled by the government owe a supplemental US$ 7.9 billion to multilateral creditors.[19] Pakistan’s overall debt-to-GDP ratio of 78 percent, however, does not tell the whole story: It appears to be lower than those of many developed nations like Japan (221 percent), the US (around 97 percent) or the UK (more than 85 percent). However, Pakistan’s problem is inherent with the short- and medium-term loan repayments over the next three years, as will be discussed in this section. Figure 2 shows how Pakistan’s debt-GDP ratio has been increasing since 2007-08, skyrocketing from 2015 onwards. Pakistan’s debt-GDP ratio presently stands at 78 percent. The figure also shows that between 2001 and 2007, there has been a decline in the debt-GDP ratio. Those few years were also the phase of comparatively higher GDP growth for Pakistan and a concomitant decline in fiscal deficits. As such, periods of relatively high growth rates in Pakistan have been associated with better fiscal management and lower debt-GDP ratios.[20]

Figure 2: Pakistan’s Gross Debt-to-GDP Ratio

Source: IMF, World Economics[21]

The threat of the burgeoning debt needs dissection. There are four broad categories under which Pakistan’s debt can be classified: multilateral debt, Paris Club debt, private and commercial loans, and Chinese debt.

Multilateral Debt: Of Pakistan's US$ 126-billion total debt, around US$ 45 billion is attributed to multilateral financial institutions. Of these, World Bank (US$ 18 billion), Asian Development Bank (US$ 15 billion), and the International Monetary Fund (US$ 7.5 billion) constitute 90 percent of the total multilateral debt, while the rest is owed to Islamic Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.[22],[23] Despite its large proportion, multilateral debt does not pose the biggest challenge owing to their long retirement tenure of an average of 25 years. The debts are largely concessional and entail soft instalments.

Paris Club Debt: The Paris Club consists of 22 major creditor countries whose role is to find coordinated and sustainable solutions to the payment difficulties experienced by debtor countries. Pakistan’s debt of US$ 8.5 billion to the Paris Club is scheduled to be repaid over 40 years with a soft interest rate of less than 1 percent.[24]

Private Debt and Commercial Loans: Pakistan’s challenge is in the increasing private debt and commercial loans that amount to US$ 7.8 billion consisting largely private bonds, such as Eurobonds and global Sukuk bonds.[25] In the last fiscal year, Pakistan raised US$ 2 billion by floating Eurobonds of 5, 10, and 30 years at an interest rate ranging from 6 percent for five years and 8.87 percent for 30 years. The apprehension is that the present levels of foreign commercial loans of nearly US$ 7 billion are expected to rise to nearly US$ 9 billion by the end of the current fiscal year.[26] There are two characteristics of these commercial loans. First, most of it is attributed to Chinese financial institutions. Second, none of these has come in benign terms: they are short-term in nature to be retired within one and three years; their rates are high, with some being pegged to the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) and the Shanghai Interbank Offered Rate (SHIBOR). These do not augur well with Pakistan’s debt condition in the short and medium term.

Chinese Bilateral Debt: The Chinese debt amounts to almost US$ 27 billion, comprising around US$ 10 billion in bilateral debt, commercial loans of around US$ 7 billion, loan of US$ 6.2 billion to Pakistan’s PSUs, and US$ 4 billion of foreign deposits with Pakistan’s central bank. Prima facie, the bilateral debt is on soft terms with a retirement period of 20 years.[27] Pakistan also has a currency swap facility with China.

Debt Repayment Pressures in the Short and Medium Term

The task of debt repayment poses significant pressure on Pakistan in the medium run. In particular, the required repayment amount of US$ 77.5 billion between April 2023 and June 2026 is equivalent to nothing less than 22 percent of the country’s GDP. These repayments will largely go to Chinese financial institutions, private creditors, and Saudi Arabia for the next three years. The picture is equally grim in the short run. During April-June 2023, the external debt servicing burden is US$ 4.5 billion. These include a US$ 1-billion Chinese SAFE deposit in June and retiring around US$ 1.4 billion Chinese commercial loan would mature. The only option left is to roll over the debts.[28]

Even if Pakistan manages to meet these obligations, the subsequent fiscal years will be more challenging, with debt servicing rising to nearly US$ 25 billion in 2024-25 (major heads being US$ 8.2 billion long-term debt repayments and another US$ 14.5 billion short-term debt repayments), and around US$ 23 billion in 2025-26 (including US$ 8 billion in long-term debt). To repay its debt and avoid a sovereign default, Pakistan’s earnings from exports, foreign direct investment and remittance inflows from foreign workers are vital. However, all three inflows will not likely be able to keep pace with the import bill as well as the mounting debt repayment pressure.

Indeed, trade deficits could increase due to global supply-side bottlenecks and currency depreciation. Pakistan hardly has a diversified export basket to provide itself with a cushion during global turbulences. The initial IMF projections of around US$ 36 billion exports for 2022-23, have now been revised to US$ 28-29 billion, partly due to the rising cost of business and the economic dislocation resulting from the political uncertainty in the country. Similarly, low investor confidence does not augur well with the FDI flow expectations of the economy.

That Pakistan might default on its foreign dues this year seems more probable than ever as the nation's dollar bonds due next year slide to a historic low, leading investors to brace for impact amidst low forex reserves and US$ 7 billion in repayments over the next few months, of which US$ 2 billion is owed to China.[29] Likewise, Pakistan's fate seems to be sealed while negotiations with the IMF for a bailout take longer than the country can afford to stave off a debt default and stabilise plummeting bond prices that have fallen by approximately over 60 percent. As Pakistan drowns in a deluge of unsustainable debt (see Appendix 1) with no relief in sight, it is essential to take a closer look at its ostensibly beneficial foreign partnerships that have kept it afloat thus far.

Forgotten Promises: The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

Not very long ago, in 2015, it was envisaged that the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) would be a revolutionary project that could make the country a leading power in South Asia.[30] However, what started as a well-meaning endeavour to mitigate the turbulent foreign relations between the two nations has become perhaps one of the most significant reasons for Pakistan's ongoing crisis. Although there had been a few large China-driven infrastructure projects in Pakistan during the decade preceding the CPEC, the BRI unlocked a new era in the country’s feeble public infrastructure sector. It appeared to have started a new pathway for Pakistan’s chronically weak power and transportation industries that have a reputation for being saddled with deficits, largely caused by ill-advised subsidies from the government.

Following its announcement of its Silk Road Economic Belt campaign—or the 'New Silk Road'—China quickly referred to CPEC the BRI's flagship, most ambitious project yet.[31] The introduction of the economic corridor in May 2013 during Chinese Premier Li Keqiang's visit to Pakistan was heralded for its promising objectives of filling the debilitating infrastructure gaps, establishing industrial zones, and opening up the potential trade routes to China through the Gwadar Port—a harbour on the Arabian Sea that was quick to win China's favour, with the help of new roads passing through the less developed regions of Pakistan. The ambitious investment of US$ 46 billion, rapidly ballooning to US$ 62 billion in pledges (comprising a fifth of Pakistan's GDP), covered dozens of envisioned high-profile Early Harvest Projects (EHP) in a country starving of foreign investments.[32]

On the geopolitical front, India has objected to CPEC since its inception in 2013 as it believes that the project would violate the country’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. India's concerns about CPEC are not just related to its territorial claims on Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK) but also the strategic implications of the project—it was seen as being part of China's larger strategy to encircle India and establish its dominance in the region. Moreover, the project could give China easy access to Pakistan's ports and potentially enable it to establish a naval base in the region, which could be a significant security threat to India. The Indian strategy of opposing the BRI and refusing to participate has limited its ability to shape regional infrastructure development. Instead, India has been focusing on building its connectivity projects, such as the International North-South Transport Corridor and the Chabahar port in Iran—where India still lags in creating a comprehensive regional connectivity strategy.[33]

For the people of Pakistan, the CPEC project engendered hope for a potential respite from their manifold energy woes. Pakistan's power shortages—a result of high energy tariffs charged by Independent Power Producers (IPPs), the neglect of power plants, crumbling transmission lines, nothing of which was helped by decades of the government's populist agendas—have had a massive economic fallout. For over three decades, the people had been plagued with incessant electricity outages that would last 10 hours a day in the big cities, and about 22 hours a day in rural regions—disrupting the flow of all revenue-earning market, industrial, academic, medical and social activities.[34]

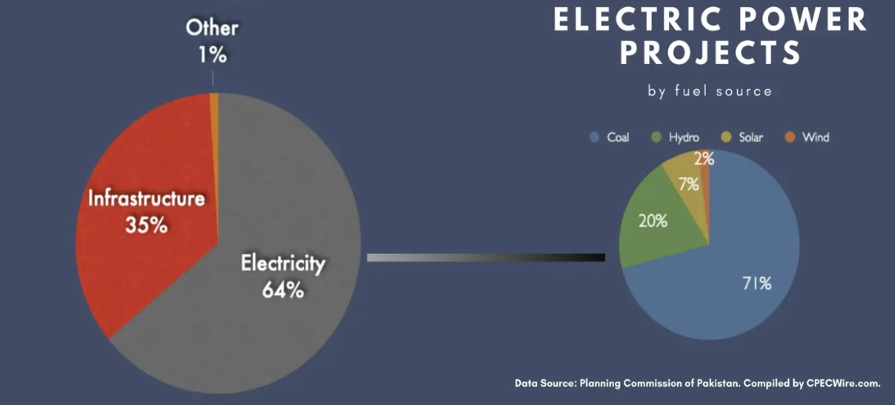

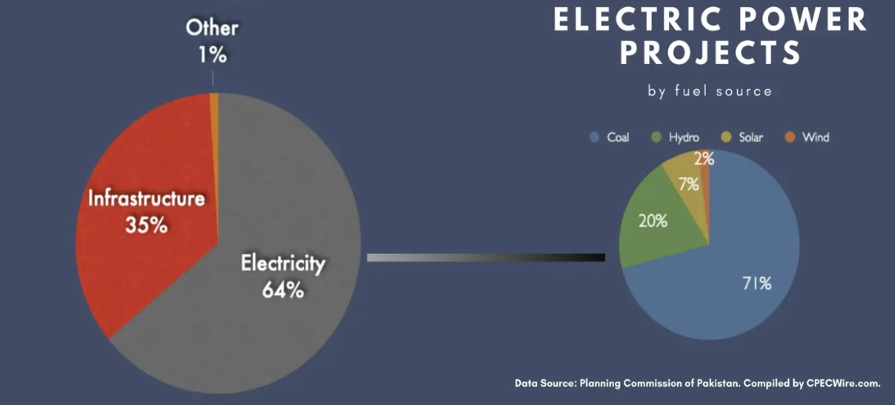

Figure 3: Components of CPEC Projects

Source: Planning Commission of Pakistan[35]

While China's decision to focus its CPEC vision on the construction of new coal-fired power plants was celebrated, in late 2021, it changed its narrative to suit the UN Climate Change Conference's (COP26) goals, pledging to not build any coal-fired power plants abroad and proposing to achieve carbon neutrality.[36] This spelt disaster for most of the coal-dependent power sectors in Pakistan owing to previously undertaken CPEC investments to increase the country's power generation capacity by a massive 20 gigawatts—thus increasing the country's current carbon dioxide emissions by 10 percent and either stalling or shelving projects mid-construction.[37] Further, the misjudged economic viability of development projects has resulted in delayed project implementation and volumes of unproductive debt.

Pakistan's untenable external debt and economic distress may have preceded the CPEC agreement, but the latter has widened the country’s current account deficits and exhausted its dwindling forex reserves. Resisting the IMF's judgement,[38] the country imported large volumes of materials for the projects before turning to the intergovernmental body for a three-year bailout worth US$ 6.3 billion and hitting a roadblock with its Chinese allies.[39]

Given that CPEC is hinged on Chinese equity holding in Pakistan's infrastructure projects—with 80 percent of all investments vis-a-vis the corridor being a long-term liability for Pakistan[40]—the project is no longer BRI's flagship component. In recent times, the flaws in the economic venture have been revealed, and in what is a costly policy misstep, China has refused,[41] on more than one occasion, to defer or restructure pending debt repayments.

In light of these circumstances, economies in the region, particularly BRI countries like Pakistan, must find the balance between their total external debt and debt to China, which is the largest creditor nation in the developing world.[42] First, Pakistan's participation in the CPEC has led to unrealistic projects that rely heavily on foreign loans. This has contributed to the country's current economic difficulties, primarily due to its reliance on external borrowing without addressing underlying economic issues such as rising trade deficits and low levels of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). As a result, the complex interactions of domestic and external macroeconomic factors have had negative ramifications for the economy. Second, Pakistan needs to scrutinise the inflow of Chinese funds more closely before committing to further repayment obligations that may prove difficult to fulfil. Among its imperatives will be prioritising credit diversification and foreign debt restructuring to manage its debt effectively.

A Tragedy of Errors: IMF et al.

Pakistan's relationship with the IMF can be explained as a tragedy of successive errors, each one progressively more debilitating than the other. Beginning in 1958, Pakistan has asked the apex intergovernmental lending body for a bailout, a record 22 times over 60 years. The IMF turned down all of those requests, as Pakistan has failed to realise all the conditionalities on bailout packages. Nevertheless, Pakistan has managed to secure funds amounting to US$ 4.172 billion from multilateral lenders like the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Islamic Development Bank (IDB) in the first five months of FY 2022-23;[43] there has also been an outpouring of relief assistance worth over US$ 9 billion from countries and organisations the world over, following the deadly floods of 2022.[44]

The country's successive borrowings, coupled with an unfavourable upward rise in the gross government debt, and refusal to scale down its expenditure on subsidised electricity, have dissuaded the IMF and its allies from extending fresh loans and restructuring old ones. Moreover, for decades, incumbent political parties have disregarded the pernicious long-term implications of doling out subsidy programs and subsequent budgetary deficits resulting from excessive government expenditures.

Most of the IMF's areas of contention and the country's predicaments are the product of its liabilities in the power sector and poor treatment of circular debt,[b] surging to an unbridled US$ 14.9 trillion by the end of 2022.[45] Pakistan has tried but failed to appease the IMF by devising a Circular Debt Management Plan (CDMP), as the government has been unwilling to hike electricity tariffs in the IMF-recommended range of Pakistani Rupees (PKR) 11-12.50 per unit.[46] It has also not been able to account in detail the Chinese financial outlay in the CPEC and give an assurance that it will not divert IMF loans to service its dues to China.[47] Labelling Pakistan's latest CDMP proposal “unrealistic”, the IMF served the country a terrible blow by rejecting its pleas on account of “a few wrong assumptions.”[48]

Pakistan has yet to reach an agreement with the IMF over a much-needed tranche of US$ 1.1 billion from the US$ 6.5-billion Extended Facility Fund (EFF) signed in 2019 amidst the looming threat of an economic meltdown. The country has returned to a market-based exchange rate and partially hiked fuel prices, thus sending inflation to a record high of 27.5 percent year-on-year in January 2023.[49] The government has also introduced new taxes and strong fiscal measures upon the counsel of the IMF, and it continues to vie from a position of disadvantage for the Fund's approval.

In the foreseeable future Pakistan will likely meet with another financial storm as it remains trapped in the debt cycle even towards the end of its EFF disbursal program. By then, its fast-depleting forex reserves would still be at near-deficient levels. The country would consequently be forced to approach the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank for more loans, requiring it to enter yet another IMF programme to bail itself out of another inflation crunch.[50]

Impulsive Alliance: The Saudi Angle

On his visit to Pakistan in 2019, Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman signed MoUs for an investment of US$ 21 billion, including an ambitious project for a deep conversion refinery and petrochemical complex with an investment worth US$ 12 billion.[51] The venture never saw the light of day, however, and has become yet another manifestation of diplomacy failure. In late 2020, Pakistan accused the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), a bloc of 57 Muslim-majority countries led by Saudi Arabia, of inaction over the Kashmir issue—regarded by then Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan as a key policy question—and threatened to hold a rival meeting that would bypass the group.[52]

Its leadership over the Muslim world having been called to question, Saudi Arabia withdrew a US$ 1-billion interest-free loan it had extended to Pakistan in November 2018; the historically cordial relations quickly turned acrimonious. The withdrawal of the loan was a blow to Pakistan, which was in dire economic straits and required foreign reserves to avoid a possible sovereign default. Saudi Arabia also refused to renew a deferred oil payments scheme, part of the same package, aimed at helping Pakistan ease its import bill.

Since then, the royal family has ostensibly distanced itself from the Pakistani top brass and side-lined Islamabad for strategic business relations with India on more than one occasion.[53] Indeed, in the backdrop of his visit to Pakistan in 2019, the Saudi Crown Prince signed US$ 100 billion in MoUs in India, even as Pakistan opposed the move—thus showing the sentimental risk that Riyadh was willing to take.

To be sure, Saudi-Pakistan relations have stood the test of time since the latter became an independent state in 1947. Sharing ties of religion, both countries have historically had close relations, with Pakistan heavily dependent on the Gulf kingdom's oil supplies and financial generosity in times of economic difficulties. Given the country's recurring cycles of depreciating forex reserves, crashing exchange rate prices and spiralling inflation, the Saudi Kingdom's reported investment plans of US$ 11 billion[54] could be a lifeline that will save Pakistan from running in the IMF's crosshairs. Saudi Arabia also raised its loan deposit with the State Bank of Pakistan to US$ 5 billion from US$ 3 billion.[55] The Gulf leader's iron patronage could be Pakistan's trump card in negotiating a restart to a stalled bailout from the IMF that requires raising the already steep electricity and gasoline prices and further increasing taxes.[56]

Contrary to popular belief, though, Saudi Arabia's relations with Pakistan transcend shared religion. The Gulf country finds Pakistan a steadfast ally and an indispensable defence partner with the requisite nuclear arsenal to deter regional attacks. Riyadh cannot afford to fragment its alliance with Islamabad given that its bete noire, Iran, has signed a US$ 400-billion Chabahar deal with China[57]— a 25-year partnership running through the CPEC and thus making Pakistan a conduit. If implemented, the project will ensure Iran's formal inclusion in the tapestry of China's BRI. The resulting economic benefits that Iran will reap are something arch-rival Saudi Arabia will find difficult to bear. Meanwhile, on the labour front, Pakistan fills the Saudi Kingdom's requirements by providing a perpetual supply of cheap workforce for the country's infrastructure projects; Pakistan is also a critical international market for Saudi Arabia's oil and foreign investment opportunities (see Appendix 2).

It remains to be seen how Pakistan reciprocates and preserves its highly remunerative end of the bargain, considering that it relies on the Kingdom for remittances worth US$ 691.8 million from a 2.5-million strong expatriate community who make up nearly 86 percent of the former's foreign reserves, out of which almost 30 percent comprise inflows from Saudi Arabia.[58] Moreover, Pakistan imports almost 25 percent of its oil from Saudi Arabia. The provision of subsidised oil has been vital for Pakistan's economy over the years. Incessant hostility displayed at international forums by Pakistan might upend their robust fraternity that was established 75 years ago. Amidst declining finances and a plummeting Pakistani Rupee, Saudi Arabia's generous policies could be Pakistan's only reprieve to survive this perfect economic storm.

The Pakistani Rupee’s Downhill Ride

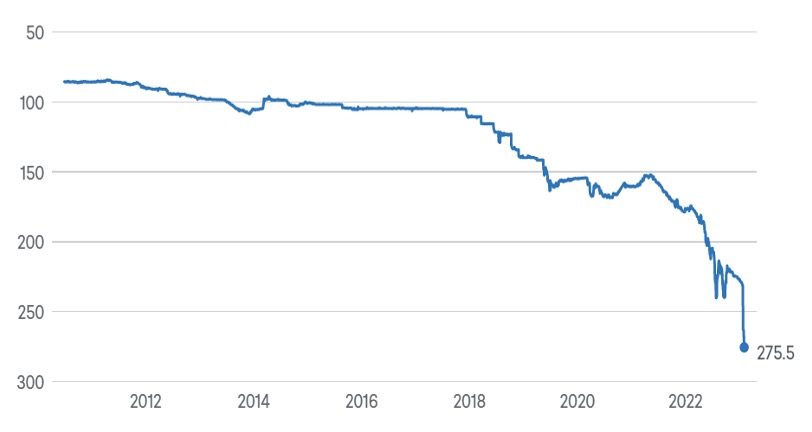

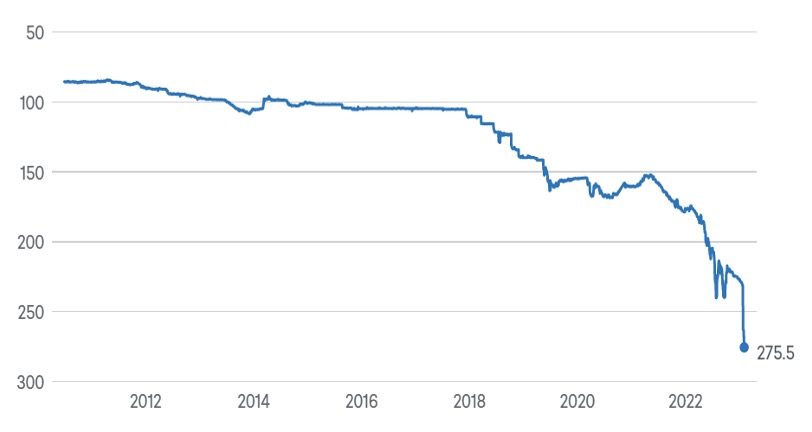

In October 2022, the Pakistani Rupee (PKR) was on the path to becoming the world's best-performing currency as it made gains of 3.9 percent[59]—to PKR 219.92 per US dollar—on the expectation of significant foreign currency inflows from the IMF and investors abroad. Unforeseen by the Finance Ministry then, the fluctuating PKR would crash to a rate of 275.5 PKR per US dollar in February 2023 and wreak havoc in the market.[60]

Figure 4: Pakistani Rupee per US$ (2010-Feb 2023)

Source: Council on Foreign Relations[61]

Essential imports in Pakistan, such as fuel, edible oil, and pulses, have become highly expensive that the government struggles with an inflated current account deficit and fiscal spending.[62] It is only a matter of time before decades of high cost-push inflationary tendencies dominate the market while local producers find it increasingly unprofitable to produce on account of expensive inputs. Coupled with nosediving forex coffers and no visible assistance from the IMF, the Pakistani people are fighting a battle with nothing less than a humanitarian crisis.

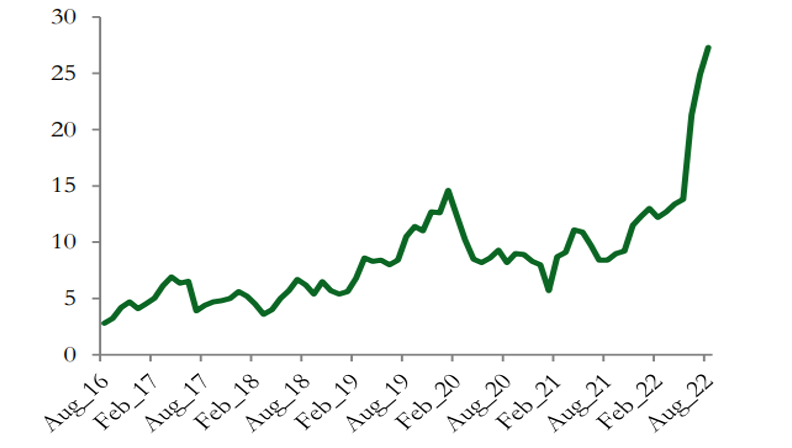

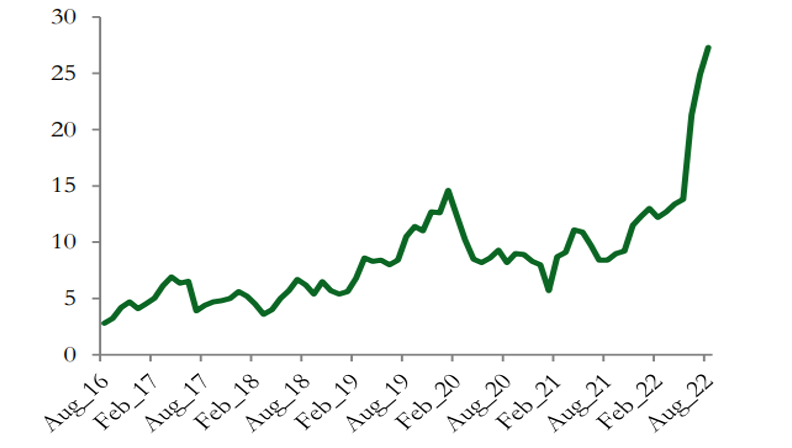

Figure 5: Pakistan's National Headline Inflation (Y-o-Y) Before and After COVID-19

Source: The World Bank[63]

On 26 January 2023, the unofficial cap on the US$-PKR exchange rate was removed to revive the IMF loan programme,[64] following an announcement by private exchange companies of the removal of a self-imposed rate cap in the open market. Since then, the PKR has tumbled down and slumped to a record low. Yet, Pakistan's currency conundrums predate its political and economic downturn. The PKR has been declining against other currencies since early 2018, when it transitioned to a free-floating exchange rate against the US$ from a managed rate.[65]

By the end of 2021, the PKR was down to 176 to the US dollar from 160 the previous year. Analysts attributed the sudden plunge to the collapse in neighbouring Afghanistan’s banking system following the US withdrawal in August 2021.[66] Further contributing to the depreciation is the supply-demand gap that prevails due to the high volume of commodities that Pakistan imports for its subsistence requirements and a subsequent surge in import demand. Sufficient to say that the currency was on the brink of hitting rock-bottom when the devastating floods occurred in mid-2022 and, compounded by political factors, exacerbated the forex crunch.

As exchange rates oscillate in the 200-rupee range, the country grapples with a tanking currency and a consequent increase in imports, thus propelling inflation to extreme levels. While Pakistan's Consumer Price Index (CPI) has risen by 27.5 percent year-on-year in 2023, taking average inflation for seven months of FY 2022-23 to 25.4 percent compared to 10.3 percent in the same period last year.[67] To woo the IMF to resume its ill-fated EFF program, the Sharif-led government has increased fuel and energy prices and raised taxes—further worsening inflation. A surge in fuel prices has only compounded Pakistan's predicaments, thus adding power shortages to a long list of reasons, including abysmal social indicators, for unfavourable FDI inflows.

Moreover, for months now, the country has been facing a crippling wheat crisis that has, in some provinces, triggered stampedes and hoarding of imported flour bags that go up to PKR 160 per kilogram as the government scrambles to provide food supplies at subsidised rates.[68],[69] Traditional economic theory says the cost-push inflationary tendency prevails in conditions of high demand and low supply; for Pakistan, with imports locked up in ships on its shore, the country is pressed for scarce dollars. Similarly, its forex crunches due to inflated import bills and unabated falls in the currency value also put upward pressure on consumers' incomes and saving capacities.

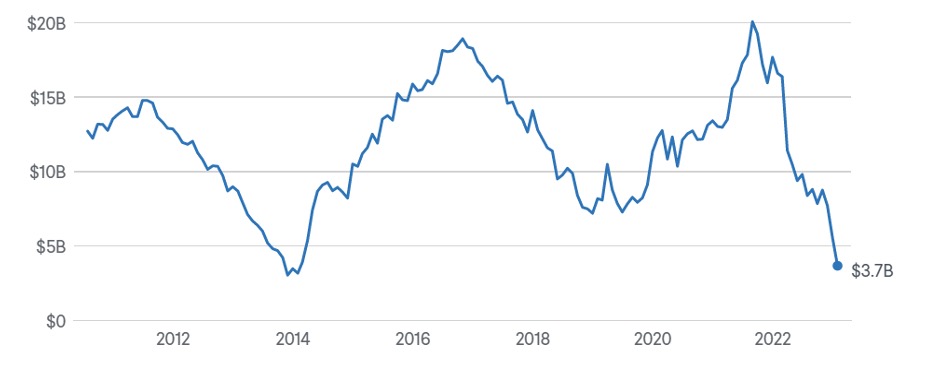

To counter rising inflation and revive the PKR, Pakistan's Central Bank hiked the interest rate by 300 bps, making the total increase 1,050 bps since January 2022.[70] Meanwhile, in early 2023, the nation's exchange reserves collapsed to a ten-year low;[71] at an alarming US$ 3.09 billion, all external debt repayments came to a halt while import payments were suspended till appropriate fiscal measures were deliberated upon.

The Vicious Cycle of BOP Crises

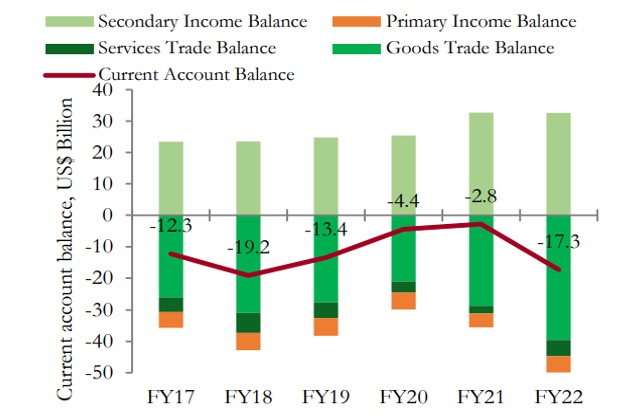

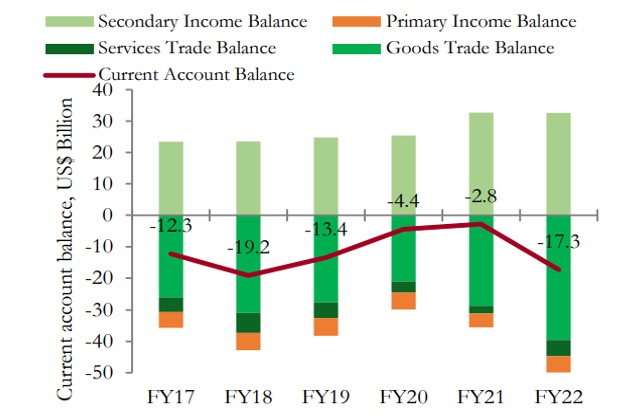

Pakistan is trapped in a gridlock with a logjam in imports and its export capacities impaired, inevitably eroding its precarious forex reserves. With a swollen Current Account Deficit (CAD)—at US$ 17.4 billion in FY22 compared to a gap of just US$ 2.82bn in FY21—the government grappled with a spell of devastating floods in 2022 and a simultaneous loss in creditor confidence as forex reserves plummeted.[72] In response, the government quickly enforced import restrictions on all commodities besides food items and medicines, and imposed austerity measures to avert a potential default on external debt.

Figure 6: Pakistan's Current Account Balance (in US$ billion)

Source: The World Bank[73]

Despite all measures, the nation's CAD plunged ten-fold to a 21-month low of US$ 242 million in January 2023, approximately 17-percent lower than the US$ 290-million deficit in the fourth quarter of 2022. The country's foreign exchange reserves also slumped to US$ 3 billion—leaving the economy vulnerable to exogenous macroeconomic shocks. Moreover, there was a pronounced decline in export earnings and inflow of workers' remittances by 7 percent and 13 percent, respectively, in January 2023 compared to the same month last year.[74]

Figure 7: Trends in Pakistan's Foreign Reserves

Source: State Bank of Pakistan[75]

The government's protectionist strategies and import restrictions backfired for a majority of the domestic industries in Pakistan that are still heavily reliant on ancillary imports to sustain their production, so much so that intermediate goods account for 53 percent of the imports while fuels and capital goods stand at 24 percent and 11 percent, respectively.[76] As a result, multiple companies across sectors have suspended operations or scaled down production levels, leading to mass layoffs, lower export productivity, and acute supply chain issues.

The economy is currently at an impasse due to the Balance of Payments (BoP) situation as current and capital account deficits worsen (see Appendix 3). Regarding the capital account, Pakistan's FDI inflows dwindle, given the unfavourable business-enabling atmosphere in the country. For years, the investment landscape in Pakistan has been characterised by tariff rates that are among the highest in the world; political volatility and terrorism; stringent tax and interest rate policies; and inconvenient security clearance procedures—all of which have deterred external investment and impeded investors abroad to finance domestic projects.[77]

Consequently, private investment has remained around 10 percent of GDP, averaging at nearly half of the regional peers and only one-third of more dynamic emerging markets in Asia.[78] Delineated by dismal productivity and low efficiency across sectors, lower FDI and insufficient technology transfer have adversely impacted growth in labour productivity, precisely shrinking gains from production and economies of scale in the country for two decades.

Pakistan experienced a surge in FDI inflows approximately between 2003 and 2007, primarily due to a combination of favourable domestic and external factors. The government took various measures to improve the country's security situation and restore investor confidence. During this period, the government introduced a number of economic reforms aimed at liberalising and deregulating the economy, reducing bureaucratic red tape, and promoting private sector growth, which improved the business environment and created a more conducive environment for FDI. The government also initiated a series of privatisation programs, providing attractive investment opportunities for both local and foreign investors.[79]

It was in the same period that the groundwork for CPEC was laid, leading to increased investment inflows from China and other countries in the region. The period was also characterised by global economic growth, which created favourable conditions for investment and attracted FDI inflows from various countries. However, the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, coupled with Pakistan's own energy crisis, political instability, and weak infrastructure, continued to hinder investment inflows and economic growth in the country.

Figure 8: Pakistan's Foreign Direct Investment (percentage of GDP)

Source: Authors’ own, using data from the World Bank[80]

That Pakistan's exports are currently falling because of its low investment and the low-saving cycle is, therefore, sufficiently justified in the context of the outflow of dollars from the country's coffers. Notwithstanding these reasons for falling FDI, another crucial factor dissuading foreign investors is the country's lack of integration with the regional and global economy. The only way to break this stubborn cycle is for Pakistan to minimise export restrictions by liberalising its protectionist policies such as high import rate tariffs, and expanding export capacities.

Coupled with diversifying its export basket to include industrial products apart from textile and rice, and taking measures to increase trade openness—a sphere where the country has consistently underperformed in comparison to its Asian counterparts, the Philippines and Vietnam[81]—could boost both growth and forex reserves in the country. Most importantly, Pakistan should diversify and expand its foreign investment partnerships beyond China, the United States, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, and the United Arab Emirates, and engage in diplomatic efforts that could open new avenues for foreign investments.

Conclusion

Current evidence points to Pakistan’s present economic crisis as having resulted from flawed economic governance compounded by political turmoil. Despite pulling over 47 million out of poverty between 2001 and 2018 through expanded off-farm employment and increased remittances—and thereby creating a model of consumption-driven growth—such rapid poverty reduction failed to translate to improved socio-economic conditions.

Even as consumption remains a growth driver, Pakistan has failed to shore up productivity-enhancing investment and exports that would have built the pillars of strong economic growth. Unfortunately, misdirected priorities of its leadership and political uncertainties got in the way. Long-term growth of real GDP per capita, therefore, has been low, averaging only around 2.2 percent annually over 2000-22.[82] Further, lack of economic prudence, due diligence and market intelligence led the economy to a low-level growth and spiralling inflation equilibrium trap. The global inflation due to supply-chain bottlenecks emanating from the Ukraine crisis, low forex reserves, burgeoning debt, and currency depreciation have further placed Pakistan on the brink of a severe macroeconomic crisis.

In April 2023, Pakistan’s central bank raised its key interest rate to a record 21 percent to combat inflationary pressures and retain foreign investors’ confidence. A high interest rate regime aimed at combatting inflation impedes the promotion of private investments.[83] The question remains how such rise in interest rate can rein inflation, as this is largely a supply-constrained situation and depreciation of the Pakistani Rupee has aggravated the situation. Economic activity has fallen with policy tightening, flood impacts, import controls, high borrowing and fuel costs, low confidence, and protracted policy and political uncertainty. What is the way through for Pakistan? Pakistan’s economic managers have two options for addressing its external debt burden. The first is through fresh loans and debt rollovers. With Pakistan’s diminished ability to access sovereign financing market due to its credit downgrade, the leadership will depend on its West Asian partners and China, not just for existing rollover but also fresh loans if it seeks to avoid a default. The specific amount Pakistan may seek will depend on negotiations with the IMF, though prima facie it seems that IMF is ready to meet up to US$ 1.1 billion of its needs if conditionalities are met. Another possibility is that Pakistan seeks pre-emptive restructuring of debt. Doing so will reduce the repayment pressure and spare scarce dollars in the economy to finance the country’s current account deficit. Again, this seems a temporary relief, and not an easy task, either.

At the same time, there is a serious need to decouple Pakistan’s economic governance from its political leadership. What appears to be an improbable proposition is also an imperative. The economy needs to be left to the specialists at this juncture of the crisis, and the present political turmoil and governance deficit will only exacerbate the situation rather than resolving it.[84]

Pakistan’s economic governance should also imbibe developing better market intelligence especially in the context of government procurement from external markets and imports. While certain nations could take advantage of the European crisis and import cheap crude oil from Russia, most have failed to do so due to either their political alignments or their lack of market intelligence; Pakistan falls in the latter category. The need for fiscal prudence cannot be overstated—one that will broad-base indirect and direct taxes, and not only cut fuel subsidies.

There is no doubt that Pakistan will need to satisfy the IMF conditionalities. IMF’s continued support as well as help from Chinese and West Asian partners are essential at this point. As Pakistan inches closer to a sovereign default, with depleting FOREX, rising food import bills and agricultural production constraints created by repeated natural disasters—it will have cascading disruptive impacts on the economy which could even lead to food riots, if not averted.

Soumya Bhowmick is Associate Fellow at ORF’s Centre for New Economic Diplomacy.

Nilanjan Ghosh is Director of ORF’s Centre for New Economic Diplomacy, and the Kolkata Centre.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Pakistan’s Debt and Liabilities Summary (June-December 2022)

| (In Billion PKR) |

|

|

R |

Provisional |

|

Jun-22 |

Dec-21 |

Sep-22 |

Dec-22 |

| I. Government Domestic Debt |

31,037.5 |

26,746.5 |

31,404.6 |

33,116.3 |

| II. Government External Debt |

16,747.0 |

14,796.5 |

18,004.5 |

17,879.8 |

| III. Debt from IMF |

1,409.6 |

1,188.4 |

1,731.4 |

1,724.8 |

| IV. External Liabilities1 |

2,275.6 |

2,055.0 |

2,440.3 |

2,486.5 |

| V. Private Sector External Debt |

3,596.3 |

3,029.6 |

3,900.3 |

3,799.2 |

| VI. PSEs External Debt |

1,675.7 |

1,205.3 |

1,805.8 |

1,792.3 |

| VII. PSEs Domestic Debt |

1,393.4 |

1,503.8 |

1,470.4 |

1,474.3 |

| VIII. Commodity Operations2 |

1,133.7 |

889.4 |

1,126.8 |

1,138.8 |

| IX. Intercompany External Debt from Direct Investor abroad |

905.1 |

785.0 |

997.5 |

931.2 |

| A. Total Debt and Liabilities (sum I to IX)6 |

59,698.9 |

51,724.6 |

62,406.6 |

63,868.2 |

| B. Gross Public Debt (sum I to III) |

49,194.0 |

42,731.4 |

51,140.5 |

52,720.8 |

| C. Total Debt of the Government - FRDLA Definition3 |

44,313.6 |

38,363.0 |

46,818.0 |

47,963.6 |

| D. Total External Debt & Liabilities (sum II to VI+IX) |

26,609.2 |

23,059.8 |

28,879.8 |

28,613.8 |

| E. Commodity Operation and PSEs Debt (sum VI to VIII) |

4,202.8 |

3,598.6 |

4,402.9 |

4,405.4 |

| As percent of GDP |

|

|

|

|

| Total Debt and Liabilities |

89.2 |

|

|

|

| Gross Public Debt |

73.5 |

|

|

|

| Total Debt of the Government - FRDLA Definition |

66.2 |

|

|

|

| Total External Debt & Liabilities |

39.7 |

|

|

|

| Commodity Operation and PSEs Debt |

6.3 |

|

|

|

| Government Domestic Debt |

46.4 |

|

|

|

| Memorandum Items GDP (current market price)4 |

FY22 66,949.9 |

|

|

|

| Government Deposits with the banking system5 |

4,880.5 |

4,368.3 |

4,322.4 |

4,757.3 |

| SBP’s on-lending to GOP against SDRs allocation6 |

474.9 |

474.9 |

474.9 |

474.9 |

| US Dollar, last day Weighted Average Customer Exchange Rates |

204.3784 |

176.5191 |

228.0465 |

226.4731 |

Notes:-

- External liabilities include Central bank deposits, SWAPS, Allocation of SDR including and Non resident LCY deposits with central

- Includes borrowings from banks by provincial governments and PSEs for commodity

- As per Fiscal Responsibility and Debt Limitation Act, 2005 (FRDLA) amended in June 2017, "Total Debt of the Government" means the debt of the government (including the Federal Government and the Provincial Governments) serviced out of the consolidated fund and debt owed to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) less accumulated deposits of the Federal and Provincial Governments with the banking

- As per revised GDP(MP) at current prices (base 2015-16) released by

- Accumulated deposits of the Federal and Provincial Governments with the banking

- Less the SBP’s on-lending to GOP against SDRs allocation (SDR 95 billion) equivalent to PKR 474.94 billion.

- Wherever mentioned, P: Provisional , R: Revised

- For conversion into Pak Rupees from US Dollars, last day Weighted Average Customer (WA C) exchange rates prepared by Domestic Markets & Monetary Management Department have been used for stocks and during the month average exchange rates for debt

- SBP enhanced coverage & quality of external debt statistics e.f March 31, 2010.

- As part of annual revision of IIP 2020, data from Dec 31, 2020 to Dec 31, 2021 has been

- The data has been revised by incorporating the private sector loans channeled through permissible offshore

Source: State Bank of Pakistan[i]

Appendix 2: Pakistan’s Trade with Saudi Arabia (2003 – 2020)

| Year |

Export (US$ Million) |

Import (US$ Million) |

Total Trade Volume (US$ Million) |

Pakistan’s Total Trade Deficit (US$ Million) |

| 2003 |

469.6 |

1416.7 |

1886.2 |

947.1 |

| 2004 |

353.1 |

1757.8 |

2111 |

1404.7 |

| 2005 |

354.9 |

2650.6 |

3005.5 |

2295.7 |

| 2006 |

309 |

3033.2 |

3342.3 |

2724.2 |

| 2007 |

295.5 |

4011.8 |

4307.3 |

3716.3 |

| 2008 |

441.1 |

5954.9 |

6396 |

5513.9 |

| 2009 |

425.7 |

3500.1 |

3925.8 |

3074.4 |

| 2010 |

409 |

3837.9 |

4247 |

3428.9 |

| 2011 |

420.2 |

4668.3 |

5088.5 |

4248.1 |

| 2012 |

455.6 |

4283.5 |

4739.2 |

3827.9 |

| 2013 |

494.1 |

3847.2 |

4341.3 |

3353.2 |

| 2014 |

509.7 |

4417.4 |

4927.1 |

3907.7 |

| 2015 |

431.3 |

3006.8 |

3438.1 |

2575.4 |

| 2016 |

380.4 |

1843.1 |

2223.6 |

1462.7 |

| 2017 |

334.5 |

2730.4 |

3064.9 |

2395.9 |

| 2018 |

316.3 |

3242.3 |

3558.7 |

2926 |

| 2019 |

404.9 |

2436.3 |

2841.2 |

2031.4 |

| 2020 |

432.3 |

1893.1 |

2325.4 |

1460.8 |

Source: The World Bank[ii],[iii]

Appendix 3: Pakistan's BOP Summary (July 2021 – February 2023)

| (Million US$) |

| Items |

Jul-Jun |

Feb |

Jul-Jun |

Jul-Sep |

Oct-Dec |

Jan |

Feb |

Jul-Feb |

| FY21 |

FY22 |

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY23 |

FY23R |

FY23P |

FY23P |

FY22 |

| Current Account Balance |

-2,820 |

-519 |

-17,405 |

-2,446 |

-1,111 |

-230 |

-74 |

-3,861 |

-12,077 |

| Current Account Balance without Official Transfers |

-3,079 |

-552 |

-17,745 |

-2,529 |

-1,205 |

-262 |

-92 |

-4,088 |

-12,312 |

| Exports of Goods FOB |

25,639 |

2,889 |

32,471 |

7,391 |

6,831 |

2,219 |

2,198 |

18,639 |

20,631 |

| Imports of Goods FOB |

54,273 |

5,039 |

72,152 |

16,380 |

13,148 |

3,929 |

3,931 |

37,388 |

47,337 |

| Balance on Trade in Goods |

-28,634 |

-2,150 |

-39,681 |

-8,989 |

-6,317 |

-1,710 |

-1,733 |

-18,749 |

-26,706 |

| Exports of Services |

5,945 |

543 |

6,950 |

1,654 |

1,940 |

610 |

574 |

4,778 |

4,488 |

| Imports of Services |

8,461 |

954 |

11,969 |

1,935 |

1,978 |

592 |

613 |

5,118 |

7,635 |

| Balance on Trade in Services |

-2,516 |

-411 |

-5,019 |

-281 |

-38 |

18 |

-39 |

-340 |

-3,147 |

| Balance on Trade in Goods and Services |

-31,150 |

-2,561 |

-44,700 |

-9,270 |

-6,355 |

-1,692 |

-1,772 |

-19,089 |

-29,853 |

| Primary Income Credit |

508 |

45 |

762 |

255 |

193 |

85 |

115 |

648 |

462 |

| Primary Income Debit |

4,908 |

319 |

6,058 |

1,283 |

1,769 |

594 |

424 |

4,070 |

3,777 |

| Balance on Primary Income |

-4,400 |

-274 |

-5,296 |

-1,028 |

-1,576 |

-509 |

-309 |

-3,422 |

-3,315 |

| Balance on Goods, Services and Primary Income |

-35,550 |

-2,835 |

-49,996 |

-10,298 |

-7,931 |

-2,201 |

-2,081 |

-22,511 |

-33,168 |

| Secondary Income Credit |

33,027 |

2,346 |

32,881 |

7,891 |

6,893 |

1,999 |

2,036 |

18,819 |

21,285 |

| General Government |

281 |

34 |

374 |

84 |

99 |

33 |

19 |

235 |

255 |

| Current International Cooperation |

34 |

1 |

54 |

2 |

1 |

7 |

1 |

11 |

52 |

| Other Official Current Transfers |

247 |

33 |

320 |

82 |

98 |

26 |

18 |

224 |

203 |

| Financial Corporations, NFCs*, Households and NPISHs |

32,746 |

2,312 |

32,507 |

7,807 |

6,794 |

1,966 |

2,017 |

18,584 |

21,030 |

| Workers' Remittances |

29,450 |

2,196 |

31,279 |

7,686 |

6,426 |

1,894 |

1,988 |

17,994 |

20,184 |

| Other Personal Transfers |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Other Current Transfers |

3,296 |

116 |

1,228 |

121 |

368 |

72 |

29 |

590 |

846 |

| Secondary Income Debit |

297 |

30 |

290 |

39 |

73 |

28 |

29 |

169 |

194 |

| Balance on Secondary Income |

32,730 |

2,316 |

32,591 |

7,852 |

6,820 |

1,971 |

2,007 |

18,650 |

21,091 |

| Capital Account Balance |

224 |

9 |

208 |

34 |

280 |

11 |

9 |

334 |

148 |

| Capital Account Credit |

224 |

9 |

208 |

34 |

280 |

11 |

9 |

334 |

148 |

| Capital Account Debit |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Net Lending (+) / Net Borrowing (–) (Balance from Current and Capital Accounts) |

-2,596 |

-510 |

-17,197 |

-2,412 |

-831 |

-219 |

-65 |

-3,527 |

-11,929 |

| Financial Account |

-8,768 |

-373 |

-11,149 |

-217 |

1,418 |

1,997 |

-999 |

2,199 |

-11,947 |

| Direct Investment |

-1,648 |

-57 |

-1,635 |

-205 |

873 |

-194 |

-71 |

403 |

-1,203 |

| Direct Investment Abroad |

171 |

34 |

234 |

97 |

1,033 |

29 |

30 |

1,189 |

113 |

| Equity and Investment Fund Shares (including Reinvested Earning |

43 |

10 |

49 |

7 |

933 |

-1 |

0 |

939 |

41 |

| Debt Instruments |

128 |

24 |

185 |

90 |

100 |

30 |

30 |

250 |

72 |

| Direct Investment in Pakistan |

1,819 |

91 |

1,869 |

302 |

160 |

223 |

101 |

786 |

1,316 |

| Equity and Investment Fund Shares (including Reinvested Earning |

1,790 |

103 |

1,825 |

342 |

203 |

174 |

88 |

807 |

1,191 |

| Debt Instruments |

29 |

-12 |

44 |

-40 |

-43 |

49 |

13 |

-21 |

125 |

| Portfolio Investment |

-2,774 |

60 |

54 |

30 |

1,001 |

-8 |

-7 |

1,016 |

-610 |

| Portfolio Investment Abroad |

-12 |

0 |

-24 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

-1 |

-19 |

| Equity and Investment Fund Shares** |

-24 |

0 |

24 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

-1 |

10 |

| Debt Securities |

12 |

0 |

-48 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

-29 |

| Portfolio Investment in Pakistan |

2,762 |

-60 |

-78 |

-30 |

-1,001 |

8 |

6 |

-1,017 |

591 |

| Equity and Investment Fund Shares** |

-294 |

-7 |

-388 |

-11 |

1 |

-1 |

6 |

-5 |

-314 |

| Debt Securities |

3,056 |

-53 |

310 |

-19 |

-1,002 |

9 |

0 |

-1,012 |

905 |

| Financial Derivatives (Other than Reserves) and Employee Stock Options |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

-1 |

-2 |

0 |

-2 |

-5 |

-2 |

| Other Investment |

-4,346 |

-376 |

-9,567 |

-41 |

-454 |

2,199 |

-919 |

785 |

-10,132 |

| Net Acquisition of Financial Assets |

1,345 |

606 |

2,490 |

36 |

-1,391 |

-69 |

-3 |

-1,427 |

1,563 |

| Central Bank |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Deposit Taking Corporations |

608 |

275 |

262 |

-21 |

-180 |

11 |

-66 |

-256 |

807 |

| General Government |

15 |

6 |

915 |

11 |

-910 |

0 |

0 |

-899 |

11 |

| Other Sector |

722 |

325 |

1,313 |

46 |

-301 |

-80 |

63 |

-272 |

745 |

| Net Incurrence of Liabilities |

5,691 |

982 |

12,057 |

77 |

-937 |

-2,268 |

916 |

-2,212 |

11,695 |

| Central Bank |

-1,468 |

0 |

-1 |

3 |

0 |

-3 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

| Deposit Taking Corporations |

499 |

-77 |

879 |

-25 |

-107 |

222 |

233 |

323 |

513 |

| General Government |

5,738 |

1,094 |

6,073 |

245 |

-519 |

-2,178 |

677 |

-1,775 |

7,357 |

| Disbursements |

9,808 |

1,200 |

11,230 |

2,206 |

3,151 |

208 |

1,192 |

6,757 |

7,211 |

| Credit and Loans with the IMF (Other than Reserves) |

500 |

1,053 |

1,053 |

1,166 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1,166 |

1,053 |

| Other Long Term |

8,060 |

43 |

7,963 |

639 |

2,791 |

118 |

1,100 |

4,648 |

4,482 |

| Short Term |

1,248 |

104 |

2,214 |

401 |

360 |

90 |

92 |

943 |

1,676 |

| Amortisation |

5,855 |

154 |

8,333 |

1,861 |

3,560 |

2,342 |

486 |

8,249 |

3,516 |

| Credit and Loans with the IMF (Other than Reserves) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Other Long Term |

5,071 |

135 |

7,829 |

1,415 |

3,228 |

1,997 |

424 |

7,064 |

3,126 |

| Short Term |

784 |

19 |

504 |

446 |

332 |

345 |

62 |

1,185 |

390 |

| Other Liabilities (Net) |

1,785 |

48 |

3,176 |

-100 |

-110 |

-44 |

-29 |

-283 |

3,662 |

(Million US$)

| Items |

Jul-Jun |

Feb |

Jul-Jun |

Jul-Sep |

Oct-Dec |

Jan |

Feb |

Jul-Feb |

| FY21 |

FY22 |

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY23 |

FY23R |

FY23P |

FY23P |

FY22 |

| Other Sector |

922 |

-35 |

2,333 |

-146 |

-311 |

-309 |

6 |

-760 |

1,053 |

| Disbursements |

2,163 |

14 |

3,138 |

81 |

173 |

4 |

8 |

266 |

1,545 |

| Amortisation |

1,253 |

25 |

1,136 |

315 |

500 |

338 |

27 |

1,180 |

660 |

| Other Liabilities (Net) |

12 |

-24 |

331 |

88 |

16 |

25 |

25 |

154 |

168 |

| Allocation of SDRs |

0 |

0 |

2,773 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2,773 |

| Net Errors and Omissions |

-619 |

-67 |

-268 |

177 |

-17 |

-39 |

-16 |

105 |

-521 |

| Overall Balance |

-5,553 |

204 |

6,316 |

2,018 |

2,266 |

2,255 |

-918 |

5,621 |

503 |

| Reserves and Related Items |

5,553 |

-204 |

-6,316 |

-2,018 |

-2,266 |

-2,255 |

918 |

-5,621 |

-503 |

| Reserve Assets |

4,473 |

-204 |

-7,331 |

-2,219 |

-2,546 |

-2,255 |

918 |

-6,102 |

-1,019 |

| Use of Fund Credit and Loans |

-1,080 |

0 |

-1,015 |

-201 |

-280 |

0 |

0 |

-481 |

-516 |

| Exceptional Financing |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| SBP Gross Reserves incl CFC less RBI Unsettled Claims*** |

18,716 |

17,795 |

11,090 |

8,602 |

6,159 |

4,004 |

4,847 |

4,847 |

17,795 |

| CRR/SCRR |

1,230 |

1,216 |

1,026 |

557 |

458 |

800 |

887 |

887 |

1,216 |

| SBP Reserves (Excluding CRR /SCRR) |

17,486 |

16,580 |

10,064 |

8,045 |

5,702 |

3,204 |

3,960 |

3,960 |

16,580 |

| SBP Reserves excluding CRR/SCRR, Net ACU, Foreign Currency Cash holding@ |

17,299 |

16,386 |

9,815 |

7,860 |

5,586 |

3,110 |

3,850 |

3,850 |

16,386 |

| DMB's Reserves - Net of CRR/SCRR |

1,387 |

1,918 |

1,632 |

1,590 |

1,369 |

1,382 |

1,297 |

1,297 |

1,918 |

| DMB's Reserves - Net of CRR/SCRR & Placements Other than FE25 |

1,384 |

1,917 |

1,631 |

1,589 |

1,369 |

1,382 |

1,296 |

1,296 |

1,917 |

| Memorandum Items: |

|

| Exports of Goods and Services |

31,584 |

3,432 |

39,421 |

9,045 |

8,771 |

2,829 |

2,772 |

23,417 |

25,119 |

| Exports of Non Factor Services |

5,945 |

543 |

6,950 |

1,654 |

1,940 |

610 |

574 |

4,778 |

4,488 |

| Export Growth (Goods) over corresponding period |

13.8 |

32.3 |

26.6 |

2.6 |

-15.0 |

-11.2 |

-23.9 |

-9.7 |

28.2 |

| Imports Growth (Goods) over corresponding period |

24.4 |

12.6 |

32.9 |

-5.8 |

-29.7 |

-36.7 |

-22.0 |

-21.0 |

44.9 |

| Current Account % of GDP |

-0.8 |

- |

-4.6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| GDP**** |

348,008 |

- |

376,099 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R: Revised; P: Provisional

* Non Financial Corporations.

** Including Reinvested Earnings

*** Includes Cash Foreign Currency holding and excludes unsettled claim on RBI.

**** GDP relates to specific period under the column. GDP on current basic price of 2015-16 as per PBS website has been converted to US$ at period average M2M exchange rate.

@ excludes Net ACU Balance from June, 2020 onward

Notes:

- Data Sources: The data is collected from a number of sources, including authorised dealers(banks, exchange companies), the economic affairs division, Pakistani missions abroad, domestic and foreign shipping and airline companies, various departments/divisions of State Bank of Pakistan and other relevant quarters.

- Accounting Treatment: ITRS data is on cash basis. Adjustments of outstanding export bills, reinvested earnings etc. are done to make the data on accrual basis. Economic Affairs Division records their loans on due for payment basis; resultantly, current account is both on cash and accrual basis.Reinvested earnings are currently being calculated as: (Reserves + Unappropriated Profits) x Percentage Shares held by Foreign Investors.

- The figures of merchandise trade used for compilation of BOP are based on exchange records which may differ from those compiled using customs

- CIF margin 17% has been used from Jul-2020 to Sep- 2021, 5.02% from Oct-2021 to Dec-2021, 7.02% for Jan-2022 to Mar- 2022, 5.65 % from Apr-2022 to Jun-2022, 4.14% from Jul-2022 to Sep-2022, 5.65% in Oct-2022 and 4.14% from Nov-2022 onward.

- Due to rounding off, figures of Trade of Good and Services, Workers' remittances, FDI, FPI and Government Disbursements may differ from source data available on

Source: State Bank of Pakistan[iv]

Endnotes

[i] https://www.sbp.org.pk/ecodata/Summary.pdf

[ii]https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/PAK/StartYear/2003/EndYear/2020/TradeFlow/Import/Indicator/MPRT-TRD-VL/Partner/SAU/Product/Total#

[iii]https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/PAK/StartYear/2003/EndYear/2020/TradeFlow/Export/Indicator/XPRT-TRD-VL/Partner/SAU/Product/Total#

[iv] https://www.sbp.org.pk/ecodata/Balancepayment_BPM6.pdf

[a] Equivalent to a few billion US dollars in today's value.

[b]A form of public debt that builds up in the power sector due to subsidies and unpaid bills.

[1] Umair Javed, “Why Pakistan Has Not Seen Any Major Public Protests despite Extreme Economic Hardship,” Scroll.in, February 8, 2023.

[2] Sana Chaudhry, “A PM No More: How the Historic Move to Eject Imran Khan through a No-Trust Vote Unfolded,” DAWN.COM, April 8, 2023.

[3] World Economics, “China | Share of Global GDP | 2023 | Economic Data | World Economics,” World Economics Research, London.

[4] The Associated Press, “China Should End Its Anti-COVID Lockdowns, the Head of the IMF Says,” NPR, November 29, 2022.

[5] Tanmay Tiwari, “Pakistan’s Economic Crisis Continues as IMF Decides Not to Bail Them Out,” cnbctv18.com, February 20, 2023.

[6] IMF, “IMF Survey: Assessing the Need for Foreign Currency Reserves,” International Monetary Fund, April 7, 2011.

[7] Saeed Shah, “Pakistan Works to Revive IMF Bailout,” WSJ, January 9, 2023.

[8] Pervez Hoodbhoy, “As Pakistan Gallops Towards Debt Default, Its ‘Unbreakable’ Bond With China Is Under Stress,” The Wire, February 22, 2023.

[9] Ajeyo Basu, “Balochistan: Massive Resistance against China Threatens Pakistan’s Security,” Firstpost, February 4, 2023.

[10] Umer Karim, “Pakistan’s Military Steps In To Manage Tense Ties With Saudi Arabia,” Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, September 1, 2020.

[11] EFSAS, “Corruption - an Inherent Element of Democracy in Pakistan?,” EFSAS.

[12] Iqtidar Hussain et al., “History of Pakistan–China Relations: The Complex Interdependence Theory,” The Chinese Historical Review 27, no. 2 (2020).

[13] Asad Farooq, “An Overview of Pak-Saudi Relations,” DAWN.COM, February 15, 2019.

[14] Gibran Naiyyar Peshimam, “U.S. Concerned about Debt Pakistan Owes China, Official Says,” Reuters, February 17, 2023.

[15] Jorgelina Do Rosario and Rachel Savage, “Sri Lanka’s Debt to China Close to 20% of Public External Debt –Study,” Reuters, November 30, 2022.

[16] Amy Hawkins, “Pakistan’s Fresh £580m Loan from China Intensifies Debt Burden Fears,” The Guardian, February 23, 2023.

[17] CEIC Data, “Pakistan External Debt, 2006 – 2023 | CEIC Data,” CEIC.

[18] Shahbaz Rana, “Pakistan’s Existential Economic Crisis,” USIP, April 6, 2023.

[19] Shahbaz Rana, “Pakistan’s Existential Economic Crisis”.

[20] ADB, “To borrow or not: Empirical evidence from public debt sustainability of Pakistan”, ADB.

[21] IMF, “World Economic Outlook,” April 11, 2023.

[22] SBP, “Pakistan's Debt and Liabilities-Summary”, State Bank of Pakistan.

[23] Shahbaz Rana, “Pakistan’s Existential Economic Crisis”.

[24] Shahbaz Rana, “Pakistan’s Existential Economic Crisis”.

[25] IANS, “Pakistan Needs to Repay $ 77.5 Billion in External Debt in Three Years.” Zee Business, April 8, 2023.

[26] CP Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh, “Pakistan’s Debilitating Debt Crisis,” The Hindu BusinessLine, February 20, 2023.

[27] Shahbaz Rana, “Pakistan’s Existential Economic Crisis”.

[28] Shahbaz Rana, “Pakistan’s Existential Economic Crisis”.

[29] Bloomberg, “Markets Brace for Pakistan Default Risk as $7 Billion Debt Looms,” The Times of India, March 2, 2023.

[30] Khurram Husain, “Exclusive: CPEC Master Plan Revealed,” DAWN.COM, May 14, 2017.

[31] Jacob Mardell, “The BRI in Pakistan: China’s Flagship Economic Corridor,” Merics, May 20, 2020.

[32] Salman Siddiqui, “CPEC Investment Pushed from $55b to $62b,” The Express Tribune, April 12, 2017.

[33] Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, “India’s Latest Concerns With the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor,” The Diplomat, August 9, 2022.

[34] Nafisa Hoodbhoy, “Pakistan Faces Struggle to Keep Its Lights,” aboard the democracy train, May 31, 2013.

[35] Arif Rafiq, “What Is CPEC? A Debt-Trap or Game Changer?” CPEC Wire, September 23, 2020.

[36] Shi Yi, “China to Stop Building New Coal Power Projects Overseas,” The Third Pole, September 23, 2021.

[37] Cecilia Han Springer, Rishikesh Ram Bhandary and Rebecca Raj, “China’s Coal Pledge Has Huge Implications for Pakistan,” The Third Pole, October 7, 2021.

[38] Executive Director for Pakistan, IMF.

[39] Executive Director for Pakistan, IMF.

[40] Safdar Sohail, “Debt Sustainability and the China Pakistan Economic Corridor,” UNCTAD/BRI PROJECT/PB 06(2022).

[41] Amy Hawkins, “Pakistan’s Fresh £580m Loan from China Intensifies Debt Burden Fears.”

[42]Soumya Bhowmick, “Understanding the Economic Issues in Sri Lanka’s Current Debacle,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 357(2022).

[43] Khaleeq Kiani, “Pakistan Received $5.1bn in July-November,” DAWN.COM, December 24, 2022.

[44] BBC News, “Pakistan Floods: International Donors Pledge over $9bn,” BBC, January 10, 2023.

[45] The Nation, “Circular Debt of Pakistan’s Energy Sector Crosses Rs4.177 Trillion,” The Nation, December 13, 2022.

[46] Ajeyo Basu, “Pakistan: Electricity to Become Unaffordable as IMF Rejects Debt Management Plan,” Firstpost, February 2, 2023.

[47] Rewati Karan, “How Pakistan Economy Was in Fast Lane for 30 Yrs but Its Engine Kept Overheating with Debt,” The Print, May 25, 2022.

[48] Bhagyasree Sengupta, “Pakistan Set to Sink Deeper as IMF Rejects Country’s ‘unrealistic’ Debt Management Plan,” Republic World, February 2, 2023.

[49] The Times of India, “Pakistan Fails to Reach Deal with IMF: What It Means for Economy,” The Times of India, February 10, 2023.

[50] The Hindu, “IMF, Pakistan Fail to Strike Deal on Bailout Package,” The Hindu, February 10, 2023.

[51] The Economic Times, “Pakistan Convinces Saudi Arabia to Revive $12 Billion Refinery, Petrochemical Complex: Report,” The Economic Times, October 24, 2022.

[52] Asad Hashim, “Pakistan-Saudi Rift: What Happened?” Al Jazeera, August 28, 2020.

[53] Sabena Siddiqui, “Saudi Arabia’s Balancing Act between India and Pakistan.” The New Arab, October 18, 2021.

[54] Saeed Shah, “Pakistan Works to Revive IMF Bailout”.

[55] Reuters. “Saudi Arabia Weighs Boosting Pakistan Investment to $10 Bln –Report,” Reuters, January 10, 2023.

[56] Saeed Shah, “Pakistan Finance Minister Pushed Painful Fixes to Win Back IMF Lifeline,” WSJ, July 15, 2022.

[57] Muhammad Tayyab Safdar and Joshua Zabin, “What Does the China-Iran Deal Mean for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor?,” The Diplomat, August 14, 2020.

[58] Khurshid Ahmed, “Saudi Arabia, UAE Contribute 45% of Remittances Sent to Pakistan in August,” Arab News PK, September 13, 2022.

[59] IANS, “Pakistani Rupee Becomes ‘World’s Best Performing Currency,’” Business Insider, October 8, 2022.

[60] Noah Berman, “What’s at Stake in Pakistan’s Power Crisis,” Council on Foreign Relations, February 6, 2023.

[61] Noah Berman, “What’s at Stake in Pakistan’s Power Crisis”.

[62] Reuters Pakistan, “Pakistan Bans Imports of All Non-Essential Luxury Goods – Minister,” Reuters, May 19, 2022.

[63] The World Bank, “Pakistan Development Update: Inflation and the Poor,” World Bank Group.

[64] Press Trust of India, “Pakistan's Currency Plunges To Rs 262.6 Against US Dollar”, OutlookIndia, January 27, 2023.

[65] Nicole Willing, “Will PKR Get Stronger in 2022?,” Capital.com, December 9, 2022.

[66] Noah Berman, “What’s at Stake in Pakistan’s Power Crisis”.

[67] Ariba Shahid, “Pakistan January CPI Rises 27.5% Year-on-Year,” Reuters, February 1, 2023.

[68] APP, “Balochistan CM for Crackdown against Wheat Hoarders,” Brecorder, January 7, 2023.

[69] Pradeep John, “A Bag of Flour Costs up to Rs 3100 in Pakistan amid Shortage, 1 Dead in Stampede,” cnbctv18.com, January 10, 2023.

[70] Business Standard, “Pak Increases Interest Rate by 300 Bps to 20% amid Rising Inflation,” Business Standard, March 5, 2023.

[71] Livemint, “Pakistan’s Forex Exchange Reserves Hit 10-Year Low,” Livemint, February 3, 2023.

[72] Shahid Iqbal, “Pakistan’s Current Account Deficit Swells to $17.4bn,” DAWN.COM, July 28, 2022.

[73] The World Bank, “Pakistan Development Update: Inflation and the Poor”.

[74] Salman Siddiqui, “Pakistan’s Current Account Deficit Falls to 21-Month,” The Express Tribune, February 20, 2023.

[75] Noah Berman, “What’s at Stake in Pakistan’s Power Crisis”.

[76] Shaheer M Ashraf , “Breaking the Boom-Bust Cycle,” The Express Tribune, January 2, 2023.

[77] Shahroo Malik, “Pakistan’s Investment Climate: The FDI Problem; South Asian Voices,” South Asian Voices, April 2, 2021.

[78] Karim Khan, “Pakistan’s Low Investment Conundrum,” The Express Tribune, November 30, 2022.

[79] My-Linh Thi Nguyen, “Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Growth: The Role of Financial Development,” Cogent Business & Management 9, no. 1 (2022).

[80] The World Bank, “Pakistan Development Update: Inflation and the Poor.”

[81] Amin Ahmed, “Pakistan Has One of Lowest Trade-to-GDP Ratios in World: ADB,” DAWN.COM, February 13, 2022.

[82] World Bank Open Data, “GDP per capita growth (annual %) - Pakistan,” World Bank.

[83] Ariba Shahid and Asif Shahzad. “Pakistan Raises Key Rate to Record 21% to Curb Crippling Inflation.” Reuters, April 4, 2023.

[84] Golam Rasul, “Why Pakistan Faces a Persistent Economic Crisis,” Pakistan Observer, April 1, 2023.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV