-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Population can be an asset or a liability, depending on how India deals with it

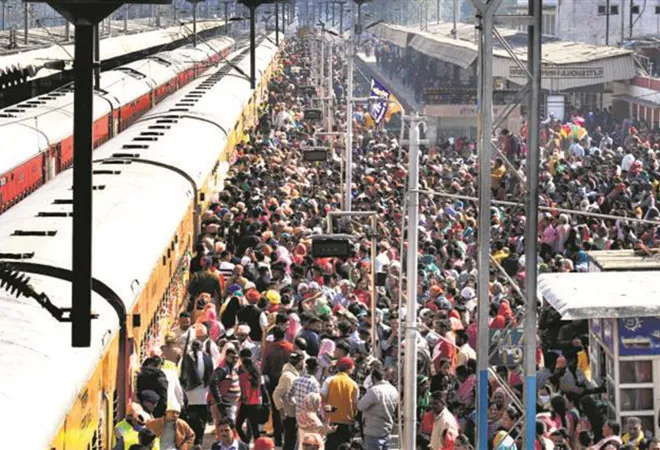

Demographic dividend is not automatic. Currently, young India not only does not have good jobs, but also seems so suffused with despair that it is not even looking for them.The share of employment in the agriculture sector stands at 43 per cent in India compared to 25 per cent in China and less than 2 per cent in the US. If India were to reduce agricultural employment to 15 per cent, it would have to create 93 million jobs over the next 25 years. The exercise of shifting rural people to an urban setting, wherein they can be productive citizens, itself is a huge effort in urbanisation and infrastructure, both physical and educational, in the country. As it is, the weakness of India’s manufacturing sector is manifest. The Make in India and the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes are aimed at offsetting this, but the challenge is huge. Manufacturing comprises just 14 per cent of the Indian economy, while it is nearly 30 per cent of China’s. The situation with jobs is apparent when, last July in response to a Parliament question, the government noted that between 2014 and 2022 some 22.06 crore applications were received by the Central government, and out of these 7.22 lakh or just about 0.3 per cent persons were recruited. Currently, young India not only does not have good jobs, but also seems so suffused with a sense of despair that it is not even looking for them. According to the World Bank, 30.7 per cent of the country’s youth was not into education, employed or under training. A WEF report of October 2022 has noted that while India has made significant progress in increasing primary school enrolment, reduced the number of children out of school, improved the quality of teaching and increased the number of teachers, ‘over the last decade, evidence points to poor learning outcomes among children.’ The report pointed to the many challenges that confront the sector, including the severe difficulties in promoting literacy and numeracy skills in rural areas. The quality of higher education is no better. A recent report in Bloomberg noted that despite a massive education industry and new colleges coming up, ‘thousands of young Indians are finding themselves graduating with limited or no skills, undercutting the economy at a pivotal moment of growth.’

The report pointed to the many challenges that confront the sector, including the severe difficulties in promoting literacy and numeracy skills in rural areas.One of the special challenges for India is that of upping the participation of women in its workforce. International Labour Organisation figures show that India’s Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) — people who are working or looking for work — is at 52 per cent as compared to 73 per cent for the US and 76 per cent in China. The reason for this low figure is that female LFPR stands at just 22 per cent compared to 70 per cent in the US and China. CMIE figures indicate that things could be worse and the LFPR has actually dropped to 40 per cent and that the number of working women in India has dropped to 19 per cent, a figure worse than in Saudi Arabia, which is at 31 per cent. Besides employment, there are other challenges. India’s public expenditure of 2 per cent on healthcare is one of the lowest in the world. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) in 2019-21 has revealed that 35 per cent children under 5 years of age are stunted. In addition, more than half the women in the 15-49 age group are anaemic. WHO figures show that India has just about five beds per 10,000 citizens, while China’s figure is 43. One of the visible signs of the government’s efforts is in the infrastructure sector. Ports, airports, roads, railway systems and housing facilities are coming up across the country. But public services are yet to catch up and low allocation of funds for health and education results in poor human capital, leading to lower productivity and low skilled labour. A demographic dividend powered the rise of countries such as Japan and China. India is also hoping that ours will power us to the future. This dividend is not automatic. Sustainable economic development requires an imaginative policy and effective implementation. In the case of China, it meant removing hundreds of millions of people from poverty and emerging as a global manufacturing superpower. With its overall population in decline, China’s challenges will change, and the principal one will be to sharply raise the productivity of its declining workforce. There will be some benefits, too. A smaller population means less stress on the environment; it reduces the unemployment rate and encourages wage rise.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Manoj Joshi is a Distinguished Fellow at the ORF. He has been a journalist specialising on national and international politics and is a commentator and ...

Read More +