-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

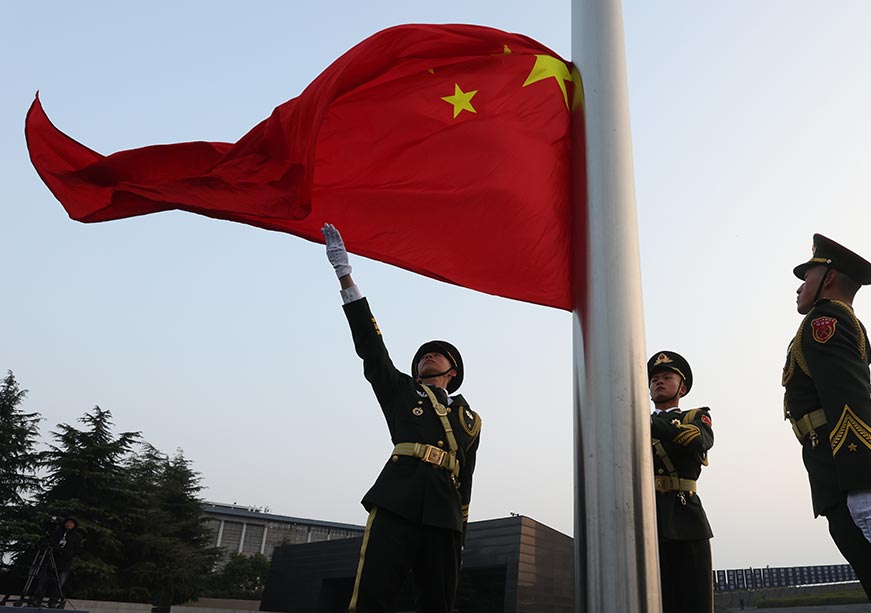

Illusion of strength partly explains Xi Jinping's cautious approach to regional disputes.

Image Source: Getty

For the China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA), 2024 was a tumultuous year marked by the arrest of numerous senior military officials as part of a comprehensive anti-corruption drive. The Central Commission on Discipline Inspection (CCDI), under President Xi Jinping’s guidance, extended its crackdown beyond the upper echelons of the PLA’s uniformed branches to include members of even China’s Central Military Commission (CMC), the highest military command organisation in the country. In November, Xi’s long-term loyalist and CMC member Admiral Miao Hua’s arrest sent shockwaves through the entire PLA leadership.

The Central Commission on Discipline Inspection (CCDI), under President Xi Jinping’s guidance, extended its crackdown beyond the upper echelons of the PLA’s uniformed branches to include members of even China’s Central Military Commission (CMC).

Despite this upheaval in its hierarchy, the PLA significantly expanded its arsenal this year, adding a vast amount of military equipment and advanced weapon platforms to its inventory. This paradox of pervasive corruption alongside enhanced military capability has fuelled debate among experts that the PLA is both corrupt and capable. The US Department of Defense’s 2024 China Military Report further buttressed this view by highlighting China’s advancements in nuclear, missile, and air-power capabilities. However, entrenched corruption, endemic organisational chaos, and limited expertise in operating hi-tech equipment continue to undermine confidence in the PLA’s combat capability. For Xi, these issues remain a source of concern shaping his cautious approach to making decisions in China’s immediate neighbourhood.

The scope for corruption in the PLA has been part of its evolutionary process as the time-honoured Chinese philosophy expected the military to be self-sufficient and provide a helping hand in China’s economy. The PLA, therefore, grew its food, reared its meat, and manufactured its uniforms and weapons. During the mid-1980s, Deng Xiaoping reduced the defence budget and authorised PLA units to open business ventures, leading to the establishment of Poly Group, China United Airlines, Kaili Corporation, and others.

Many of these business ventures were either led by princelings or dominated by their majority shareholdings. These enterprises benefitted from favourable tax benefits and other preferences, entrenching deep-rooted collaboration between the party and the military top leadership. This nexus powered massive corruption, money laundering, and other shady activities. At the lower level, PLA units dabbled in multiple illegal ventures, including hospitality, construction, prostitution, gambling, and smuggling among others. As the military kept firm control over armed power in society, these activities went unchecked, eventually seeping into the PLA and leading to the sale of promotions, moonlighting, falsification of training regimes, and even illegal diversion of military petroleum to commercial markets.

The scope for corruption in the PLA has been part of its evolutionary process as the time-honoured Chinese philosophy expected the military to be self-sufficient and provide a helping hand in China’s economy.

The party, in response, strove to stop these activities through regulations in 1993 and 1995 and finally, banned the PLA’s all commercial activities in 1998-99. However, the ban has been partially successful as the PLA’s many major corporations have survived, and corrupt practices continue in the PLA.

One of the primary sources of corruption in the PLA comes from its promotion system, where political and ideological reliability often outweighs merit and technological expertise. There are no clear, measurable benchmarks to assess a candidate’s political and ideological trustworthiness, making the process extremely discretionary which forges a patronage network, where senior officers oversee a cohort of junior officers beholden to them. They promote and protect them from sundry investigations and consequently, if a senior general is caught in an anti-corruption drive, the entire patronage network falls under the CCDI’s microscope. This process makes the PLA’s organisational structure inherently unstable during high-level prosecutions. In the last almost two years, Xi has arrested more than 15 senior-most military officers, including service chiefs, political commissars and CMC members. The level of chaos, therefore, inside the PLA and its multiple patronage networks is difficult to even imagine.

The enormity of corruption in the PLA is apparent from its spread into virtually every establishment connected to China’s defence sector. Multiple defence industry officials have been prosecuted for corruption, illegal outsourcing, and the use of defective, low-quality components. Even a prestigious programme head, such as Hu Wenming, the chief architect of China’s aircraft carrier programme, was arrested for bribery, violating party discipline, and engaging in superstitious practices. Similarly, Liu Shiquan, head of NORINCO (North China Industry Corporation), was detained alongside Wu Yansheng and Wang Changqing, the respective leaders of CASC and CASIC, China’s largest missile manufacturers. Allegations have also surfaced on the misuse of $16 billion research and development funds for fighter jet engines, leading to sub-par engine performance. In response, the CCDI has launched investigations into China’s arms procurement decisions, going back to 2017.

Even a prestigious programme head, such as Hu Wenming, the chief architect of China’s aircraft carrier programme, was arrested for bribery, violating party discipline, and engaging in superstitious practices.

These revelations raise serious question marks over the quality and reliability of China’s missiles, aviation programmes, land warfare weapons, and naval platform acquisitions among others. If corrupt generals promoted mostly corrupt junior officials and established personal fiefdoms inside the PLA, while corrupt chiefs of public sector defence industries drove defence procurements for their parochial interests, it is possible that much of China’s military modernisation consists of Potemkin procurements.

Since the Chinese civilian and commercial sector has grown rapidly, Xi Jinping has been able to marshal vast resources towards building a modern PLA. However, the top military leadership appears to have exploited large-scale weapon procurements as personal enrichment opportunities, undermining genuine capability augmentation.

A deeply corrupt PLA is inclined to flaunt its military assets to project an illusion of strength and capability that could collapse in a real battle. This underlying consciousness partly explains Xi’s cautious approach to regional disputes, as he remains distrustful of the PLA’s organisational efficiency and combat capabilities. This should be factored in by nations like India when facing a seemingly more amenable Beijing and prepare accordingly. It is time to build domestic capabilities and not be lulled into a false sense of security.

This commentary originally appeared in Financial Express.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Professor Harsh V. Pant is Vice President – Studies and Foreign Policy at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. He is a Professor of International Relations ...

Read More +

Atul Kumar is a Fellow in Strategic Studies Programme at ORF. His research focuses on national security issues in Asia, China's expeditionary military capabilities, military ...

Read More +