Introduction

The Indo-Pacific region is home to 60 percent of the world population[1] and is where some of the world’s busiest marine trade routes are located;[2] it is therefore a robust market for economic partnerships. In recent years, the region has attracted increasing attention for a number of reasons, foremost among them the rise of China. Other reasons include non-traditional security threats such as climate change, the regulation of digitisation, and cybersecurity. Those who have stakes in the Indo-Pacific are either participant countries,[a] comprising those that are within the geographical space; or else external countries who are either already engaged with or are keen to engage with the region to promote their own strategic and economic interests.

To be sure, there is yet to be a clear consensus on the geographical definition of the “Indo-Pacific region”; a shared, loose understanding is that it extends from the Indian Ocean to the Western Pacific.[3] There is also ambiguity on the context around which the term originated. Where there is clarity, nonetheless, is that there are parallels between the Indo-Pacific policies of the United States (US), India, Japan, and Australia—all espousing freedom of navigation and regional stability—as well as that of the ASEAN Outlook[4] of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

This paper examines the role of the European Union (EU) in the Indo-Pacific region from the lens of international trade and its interaction with geopolitics. It uses a multi-disciplinary approach to analyse the geopolitical and economic aspects of the EU’s engagements in the region, and addresses the question of whether the EU can serve as a counterweight to China, on which many countries in the Info-Pacific are growing increasingly dependent. The paper analyses the trade ties between the Indo-Pacific and select EU countries, examines literature on trade models estimating the impact of trade within the region, and uses the framework of game theory[b]to explain the potential of trade deals between the EU and countries of the Indo-Pacific. It also ponders the role that minilateral organisations can play in nurturing an economic and political atmosphere that is conducive to stronger partnerships.

European countries recognise that the Indo-Pacific has become the principal growth region of the world, and in the past few years have started building their presence in the region; indeed, the European Union (EU) views itself as a normative leader in the context of the Indo-Pacific.[5] This represents a shift in the EU’s earlier stance—largely echoing that of the US—to maintain a distance from the Indo-Pacific.

The EU is dependent on maritime traffic that traverses the Indian Ocean; it is therefore in the EU’s direct interest to complement efforts towards the stability and security of the world’s busiest shipping lanes that pass through the Indo-Pacific.

Table 1: Key Policy Advances for Europe’s Role in the Indo-Pacific

| DATE |

ADVANCES IN EU STRATEGY |

KEY MESSAGES |

| 2016 |

European Union Global Strategy report |

The strategy[6] calls for a more proactive EU that will work to preserve multilateralism and the rules-based global order. It outlines certain directives for the EU in terms of a revamped foreign and security policy, and a reiteration of the aim of promoting international law. This is in keeping with the expansion of the EU’s role as it engages with regions outside its immediate neighbourhood |

| 2017 |

President of the European Council participated in the ASEAN Summit |

The president of the European Council participated in the ASEAN Summit for the first time. |

| 2018 |

FTAs with Singapore, Japan and Vietnam finalised. |

Negotiations were finalised for “new generation” Free Trade Agreements with Singapore, Vietnam and Japan, and a Strategy to connect Europe and Asia was adopted.[7] |

| 2021 |

EU adopted conclusions to the EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific |

The EU adopted conclusions to the EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific demonstrating the recognition that the Union accords to the region alongside the indication of developing closer cooperation with countries which comprise the region. The 2021 Strategy document is testament to the EU’s envisioned role and serves as the initial stepping stone for the organisation to define its involvement. |

| September, 2021 |

Final EU Strategy document |

The final Strategy document is set to be drawn up by September 2021 outlining the sectoral areas of cooperation encompassing ocean governance, health, research and technology, security and defence, connectivity as well as the mitigation of human and economic effects of the COVID-19 crisis with the aim to work towards sustainable and inclusive socio-economic recovery and the building of resilient response systems.[8] |

Source: Authors’ own.

The EU has already cultivated strategic partnerships across the Indo-Pacific region going beyond trade links to cover other areas like fostering and upgrading institutional ties with regional groupings such as the ASEAN.[9] Table 2 highlights EU’s existing contributions and the potential areas of cooperation in the region, in accordance with the EU’s strategy document for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. All these spheres of cooperation are in line with the Agenda 2030 defined by the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Table 2: Areas of Cooperation between EU and Indo-Pacific

| Areas of Cooperation |

| EU’s Existing Contributions |

· Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Assistance

· Tackling Climate Change, Biodiversity Loss and Pollution

· Partnerships and Free Trade Agreements

· Disaster Risk Reduction

· Upholding International Law, including Human Rights and Freedom of Navigation

|

| Potential Partnership Domains |

· Ocean Governance

· Research and Technology

· Connectivity

· Health

· Strengthen Regional Organisations

· Intensify Cooperation in Multilateral Fora

· Reinforce work on tackling Global Challenges such as Climate Change

|

Source: European Union External Action Service[10]

The primary motivation behind the EU’s intent to deepen its role in the Indo-Pacific is to strengthen multilateralism and help preserve a rules-based international order.[11] Cooperation in areas of global concern such as connectivity, maritime security, human rights, climate change, and digitalisation form the pillars of deepening partnerships and comprise common aspects of cooperation covered by the guidelines of individual countries as they look to build upon existing ties with the Indo-Pacific. However, it is unlikely that the EU will in all instances act as a composite unit. Individual member countries do have their own approaches, imperatives and limitations (as will be discussed later in this paper).

The EU stands to offer institutional diplomacy and economic and security partnerships in the Indo-Pacific.[12] At the institutional level, the participation of the EU has to be on well-devised and viable grounds which can be translated to more tangible forms of cooperation. One such area can be assistance in the enhancement of standardisations and quality control where the EU can provide technical knowhow. The EU is, after all, a recognised global leader in standards, most importantly in terms of data protection and governance.

The Geopolitical Foundations of Economic Relations in the Indo-Pacific

The US retreat from global politics which began during the Obama administration gave rise to speculation that the US will cease to directly intervene in the geopolitical affairs of different regions. Under the Trump administration, the US proceeded to play what was often seen as a ‘transactional’ role. The EU started to be seen as possibly an alternative[13] or complementary to the US as it leaves a supposed vacuum in the Indo-Pacific. However, it remains to be seen whether indeed such a vacuum will emerge from the US’s foreign-policy decisions.

What is clear is that Trump’s uncompromising approach towards China served to enhance the prominence of the region, and helped bolster the stance of Southeast Asian nations who have been reluctant to articulate positions that could be construed as counter-China. For instance, on the contestations around the South China Sea, countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia have more recently begun voicing concerns regarding China. The ASEAN itself, which has historically been reserved on the subject of the Indo-Pacific – given the very name’s latent anti-China connotations – released the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific in 2019 and signalled its intent to leave the sidelines.[14]

While early evidence points to US President Joe Biden assuming a more conciliatory approach towards China, it does not foretell a scenario in which the US would no longer actively engage in the region. There are commonalities in Washington’s and Brussels’s overall approach towards the Indo-Pacific, primarily in their emphasis on the preservation of the rules-based order, and multilateralism. The European Commission (EC) would, nonetheless, prefer to steer clear of the US-China contestations in the Indo-Pacific. Countries like France and Germany, and the Commission too, are looking to address the strategic challenges in the region without discounting the countries’ economic dependency on China. Germany, for instance, has remained largely favourable towards China[15] while simultaneously, its Indo-Pacific strategy underscores the need for China to respect international law and refrain from unilateral actions in the South China Sea. The Chinese conundrum has indeed become a crucial geopolitical factor that necessitates the EU countries to actively engage with the Indo-Pacific countries.

Independently of the US, the EU engagement can take the form of both strategic partnerships as well as collaboration in sectors such as cybersecurity, digitisation, and climate action. This in turn could pave the way for enhanced connectivity between the two regions.

Trade partnerships between EU and Indo-Pacific

Economically, the EU is highly dependent on both China and the US as they are its largest trading partners; therefore, any churn in the geoeconomics of the Indo-Pacific inevitably has a bearing for European nations. Trade relations between the European countries and those of the Indo-Pacific have been going on for years. However, the development of “Indo-Pacific” is more of a focus on the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean as a single maritime entity.[16] Indo-Pacific countries aim to establish a multipolar, rules-based trading system in the region. The highest traded items of the EU member countries comprise of energy resources, food items, and consumer goods. Majority of this trade takes place through maritime routes.

India’s comparative advantage lies in its agrarian sector and therefore its key exports to the EU comprises of primary products, energy resources, and raw materials, while it imports mostly machinery, vehicles, and manufactured products.[17] The volume of bilateral trade has declined after 2011, as a result of the high tariff barriers and the use of trade defense instruments. Meanwhile, India’s important export items—i.e., agricultural goods, face high trade barriers in the EU countries.[18] Besides the trade in goods, the software industry of India has made it a potential match for Europe’s requirements for its digitalisation strategies.

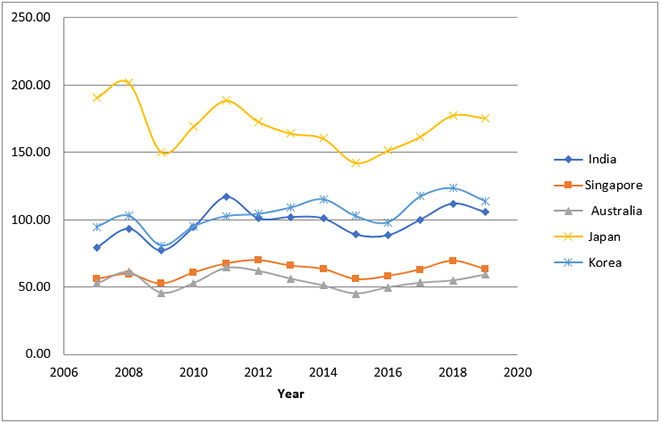

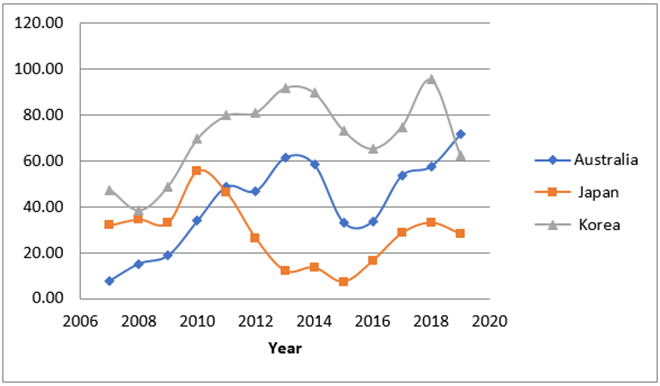

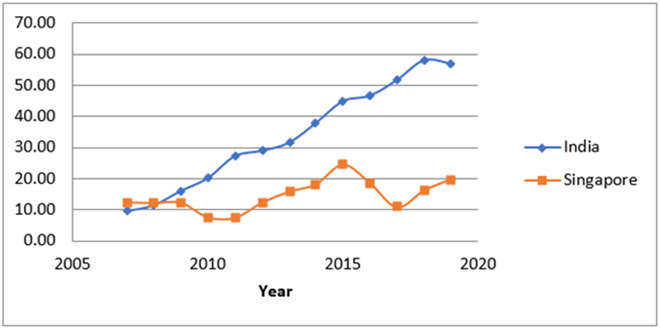

EU has one of its largest trade volumes with Japan, after India and Singapore, mostly in machinery and transport equipment. The drop in trade volume in 2009 was due to the global financial crisis. Even as trade recovered by 2011, the subsequently declining trade volume was possibly because of tariff barriers; those tariffs would finally be done away with upon the creation of the EU-Japan Economic Partnership in 2019.[19] Similarly, the dip in EU trade with South Korea in 2009 was due to the global crisis. The volumes have gone up after the EU-South Korea Free Trade Agreement came into effect in 2011.[20] A similar growing trend in trade volumes can be observed for both Singapore and Australia.

Figure 1: EU trade volumes with Indo-Pacific countries (in USD billion)

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), The World Bank[21]

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), The World Bank[21]

Automobiles make up a large portion of EU’s export basket. Germany and France are some of the biggest players in this sector[22] and they are known for their backward participation in the Global Value Chains (GVCs)—this implies that they remain dependent on the import of intermediates.[23] The Indo-Pacific countries provide a huge market for the final products.

Trade between France and Singapore visibly expanded in 2019 as a result of increasing exports of aeronautics, manufactured goods, textiles and beverages from France. Meanwhile, 46.9 percent of France’s imports during the same year were from Singapore, constituting intermediaries, refined petroleum, and pharmaceuticals.[24]

To be sure, EU as a trade bloc has a high degree of dependence on China. The growing economic potential of the Indo-Pacific region could be the EU’s way out this reliance.

The COVID-19 pandemic was able to make this diversion possible to some extent as countries like India, Japan, Singapore and South Korea emerged as key suppliers of COVID-19 gear such as test kits and PPEs, and presented themselves as alternatives to Chinese supplies.[25] There are other indications of a potential geoeconomic diversion in the region: initiatives such as the joint collaboration between the governments of France and Singapore to act on the agri-food trade disruptions due to pandemic;[26] and a trilateral dialogue between India, France and Australia also aimed at resolving the challenges posed by the pandemic by promoting stronger bilateral relations.[27] The efforts, however, must extend beyond partnerships meant to tackle the pandemic.

China’s involvement in Indo-Pacific and across EU

In recent years, there has been greater vigour in intra-region partnerships with countries increasingly looking among themselves and with extra-regional actors to counter China. China today is a significant trade and investment partner for almost every Indo-Pacific country and this is attributed to the country’s key position in the regional value chains. China has also managed to extend its geopolitical footprint to other parts of the globe such as Africa and Europe through its flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The BRI has brought associated challenges such as debt-traps, non-transparent investments, and intervention in domestic politics of the Indo-Pacific countries and also those at the heart of Europe. What were initially civilian infrastructure projects such as the construction of sea port facilities, for instance, have been turned into dual-use facilities with the presence of Chinese naval forces as in the case of Djibouti; by the attrition of sovereignty like in Hambantota; or by a complete acquisition as witnessed in Athens.[28] Moreover, Beijing’s lack of transparency regarding its infrastructure initiatives, and its practice of “wolf warrior” diplomacy and predatory economics, have resulted in apprehension and unease.

IP-China noodle bowl of trade ties

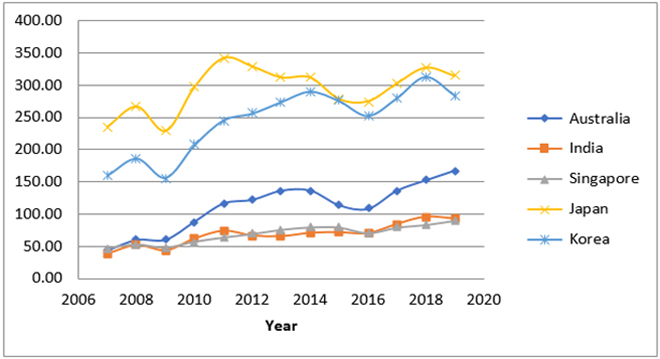

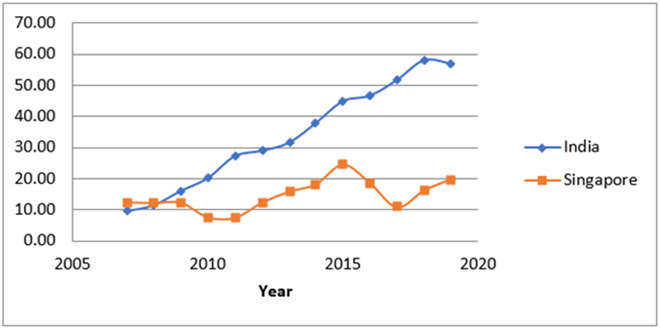

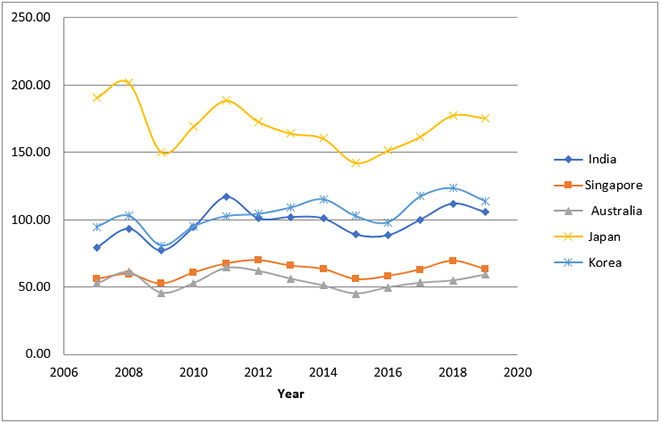

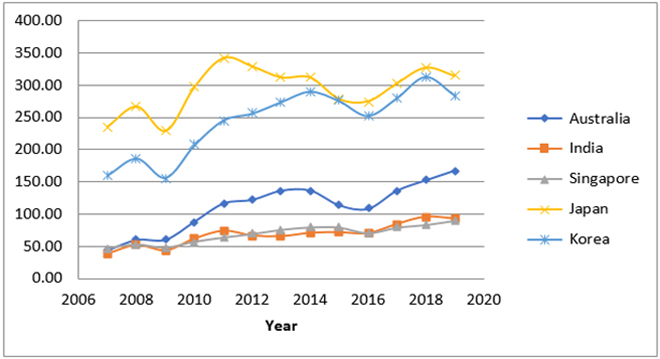

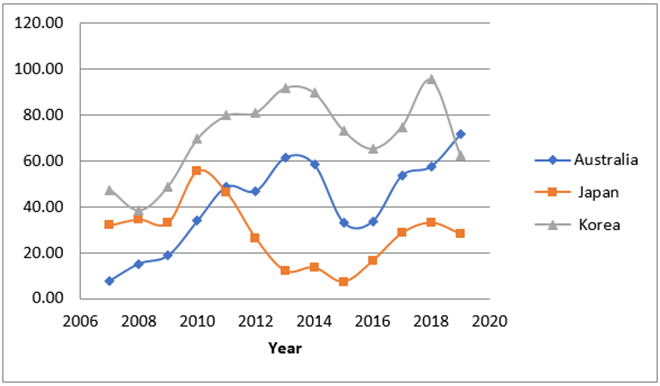

Among the Indo-Pacific countries, Japan, South Korea and Australia enjoy trade surplus against China, while India and Singapore record a deficit. From a mercantilist perspective, trade surplus in goods is perceived to be a superior trait. However, the experience of Japan, Australia and South Korea tell a different story. China happens to be the largest trade partner of all three countries and thus contributes to a large percent of their GDP. A decline in Chinese demand will not be desirable for these economies in the long run despite their political reservations against China. China’s trade volume with Indo-Pacific countries has historically been high and continues to increase. The dip in trade volume in the years 2008-09—as seen in Figures 2, 3 and 4—was due to the global financial crisis. This gradually returned to pre-financial crisis levels and there have been only a few instances of a decline in the total volume of trade relative to 2008 estimates.

Figure 2: China’s Trade Volume with Indo-Pacific countries (In USD billion)

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), The World Bank[29]

Figure 3: China’s Trade Surplus with India and Singapore (In USD billion)

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), The World Bank[30]

Figure 4: China’s Trade Deficit with Australia, Japan and South Korea (In USD billion)

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), The World Bank[31]

The indispensable role of China in the Indo-Pacific is seen in the involvement of technologically developed countries like Japan and Korea in the manufacturing of high-tech components required for the production of smartphones. These components are then assembled in China and supplied to the rest of the world.[32] Similarly, Australian agricultural exports are largely dependent on the GVCs, with a large amount of imports coming from China. Developing countries like India also enter the GVCs from the downstream, which is characterised by the imports of intermediate goods.[33] This is amongst the reasons why countries in this region are unable to completely diversify their trade towards the West.

Recent developments have forced these economies to rethink their reliance on China. The India-China military standoff in June 2020, the imposition of an 80-percent tariff on Australian barley and suspension of import permits for beef processing plants,[34] and most importantly, the supply chain disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic—have all triggered shifts in economic alignments of the Indo-Pacific countries. The alternative is to increase domestic production or find substitute import and export markets.

Stronger trade ties between Indo-Pacific and EU countries as an alternative to China can help diversify value chains, expand markets, and increase bilateral investments. This can pave the way for a more secure global economy in the long run.

EU-China geoeconomic interdependence

An export-oriented growth strategy and large foreign investments are the primary contributors to the Chinese success story, making it a dominant player in global trade, along with the US. This inevitably brings up the role of the EU as China’s largest trade partner and key investor. Although diplomatic relations between the two have been amicable since 1975, it was only in 2003 that they mutually acknowledged each other as strategic partners with the announcement of the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP).[35] China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001—which became possible only after the EU and China reached a bilateral agreement—marked the beginning of the modern-day Sino-European relations.[36]

However, more recent developments such as the large-scale infrastructure investments of China in Europe, and Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) regulating one-tenth of Europe’s seaport capacity,[37] have raised concerns in Brussels. Nonetheless, EU member countries do not have a unified position on China, and mapping the degree of “friendliness” of these states towards China is a complex task. Moreover, many countries in the EU view politics and economics through distinct lenses: while they might have concerns regarding China’s strategic overtures, they would not summarily discount their economic ties with Beijing.

The EU’s biggest imports from China are manufactured goods—more specifically tech goods, including telecommunications equipment and computers; it mostly exports vehicles and aircraft to China.[38] The financial crisis of 2007 witnessed declining rates in trade volume, which would recover by 2010. Again, in 2012 the Euro Crisis had an impact on bilateral trade, even as China tried to promote imports from EU to revive the prevailing demand conditions.[39] An important aspect of EU-China bilateral trade is the backward GVC participation of EU—i.e., it depends on China for the import of intermediate products, and as a consequence, the domestic value added in EU’s export basket declines. This, along with large Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) in China from the EU countries, explains the persistent trade deficit that EU runs against China. From being completely closed to FDI till the 1980s, China has evolved to becoming a source of significant amounts of outward FDI in recent years.[40] EU’s trade deficit with China was at a record high in 2008 at US$ 160.71 billion and continues to be substantial at US$ 150.43 billion in 2019 (see Table 2). The increasing asymmetry in trade along with decreasing market share of EU’s exports in the global markets is bound to bring uncertainty to the future of Sino-European economic relations.

Table 3: EU-China Trade (in USD billion)

| Year |

Chinese Exports to EU |

Chinese Imports from EU |

Trade Volume between China and EU |

China’s Trade Surplus with EU |

| 2007 |

245.56 |

110.97 |

356.53 |

134.60 |

| 2008 |

293.36 |

132.65 |

426.01 |

160.71 |

| 2009 |

236.44 |

127.77 |

364.21 |

108.67 |

| 2010 |

311.43 |

168.37 |

479.80 |

143.06 |

| 2011 |

356.22 |

211.16 |

567.39 |

145.06 |

| 2012 |

334.27 |

212.07 |

546.34 |

122.20 |

| 2013 |

337.80 |

219.84 |

557.64 |

117.96 |

| 2014 |

370.09 |

244.08 |

614.17 |

126.02 |

| 2015 |

355.14 |

208.66 |

563.80 |

146.47 |

| 2016 |

338.31 |

207.98 |

546.29 |

130.32 |

| 2017 |

371.17 |

244.80 |

615.97 |

126.38 |

| 2018 |

409.45 |

273.49 |

682.95 |

135.96 |

| 2019 |

426.74 |

276.30 |

703.04 |

150.44 |

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), The World Bank[41]

China’s BRI, averse to foreign investors and likely to promote subsidised Chinese companies—has pushed Sino-EU relations further downhill. The project was strongly condemned by countries like France, Germany and UK, with the EU president declaring China as a “systematic rival”.[42] The US-China trade war could have been an opportunity for EU to negotiate trade relations with China; instead, it adversely affected the business of European automobile companies operating in China.

However, the perception and approach had been different until recently, with respect to economic relations. The EU felt that the US had betrayed its allies by unilaterally imposing trade barriers. In a similar act, Brussels and Beijing agreed to the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) in December 2020, provoking sharp criticism of the EU for turning a blind eye to Beijing’s human rights violations in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, the sanctions it imposed against Australia, and its unwarranted military advances in the Himalayas.[43] The agreement has also caused strain on the relations between the EU and its allies by showing that the Union prefers a bilateral deal with a country that has contributed significantly to the breakdown of the multilateral system.[44] The EU’s defense is that the agreement will resolve the various grievances faced by European companies: it prohibits forced technology transfers and levels the playing field for European investors, besides being limited in scope compared to similar agreements that the EU has signed in the past with countries like Canada, Japan, and the UK.[45]

Implications of EU-Indo-Pacific cooperation

The China factor in the EU’s involvement in the Indo-Pacific will be crucial in understanding the nature of such involvement in the region, and ultimately its efficacy. The extent of EU’s engagements in the Indo-Pacific will be determined by whether the EU will continue to be wary of Beijing’s long-term intentions or whether it will decide to act on its apprehensions[46] and pick sides in what might an even more divided world order in the near future.

The COVID-19 pandemic, and the lockdowns that governments across the world implemented as a response, have inevitably led to supply chain disruptions. The EU countries acknowledge the need to build more resilient supply chains. The EU happens to be one of the largest importers of manufacturing intermediaries from China and a pause on that caused cascading impacts: the productivity of export industries declined, and consequently, consumer goods became scarce.[47] In other words, the pandemic has highlighted the urgency of on-shoring domestic production.[48]

The Indo-Pacific could be the EU’s way out of dependence on China by becoming the EU’s new markets for its exports. The challenge, however, is that the Indo-Pacific countries themselves are highly integrated with the Chinese economy. This could hinder any efforts toward geoeconomic re-alignment in the post-pandemic world. Better information on the gains and losses from strategic and economic interactions with the Indo-Pacific can guide the policymakers of Europe.

The Future of EU-Indo-Pacific Trade Integration

The Indo-Pacific region accounts for 62 percent of the global economy (in current US$) according to World Bank estimates, and 46 percent of global merchandise trade pass through the region.[49]

What do trade models suggest?

Given the importance of the region in the Global Value Chains, and the increasing asymmetry in Sino-EU trade relations, can members of the EU forge a lucrative trade deal with members of the Indo-Pacific to counter the growing influence of China in both regions? The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the disadvantages of overdependence on a single country. If highly specialised and interconnected GVCs become more spatially dispersed and regionalised, transport costs could decrease, as well as, and more importantly, vulnerabilities to global risks and supply chain disruptions. At the same time, however, highly regionalised value chains might prevent firms and economies from efficiently allocating their scarce resources, from increasing their productivity or realising higher potentials from specialisation. Moreover, greater reliance on a more limited geographical area may reduce the flexibility of manufacturing firms and stunt their ability to find alternative sources and markets when hit by country- or region-specific shocks. Growing dependence on China has exposed geo-political tensions.[50] The EU and Indo-Pacific countries can take the opportunity to engage in deeper economic and trade integration with each other.

First, given the anti-China sentiment that is running high due to the COVID-19 pandemic, any approach towards an economic partnership with China must be viewed with caution. Second, several countries in the Indo-Pacific region are overdependent on the Chinese economy not only as a final destination for their goods, but also as a source of investment in their domestic sectors. Disruptions due to the pandemic, and blockades on goods originating from China have revealed the downside of being overdependent on the Chinese economy. This has raised the stakes among countries across the world for diversifying their economic ties. Furthermore, Indo-Pacific countries like Vietnam and Thailand have already established themselves as manufacturing hubs in the lower end of the value chain. High-value chain activities are predominantly in the developed nations, many of which are part of the EU—e.g., Germany, France, and the Netherlands. Indo-Pacific countries like Japan and South Korea also have a strong presence in the exports of commodities from the higher end of the value chain. Thus, a trade agreement between members of the EU and the Indo-Pacific can form a link between the various value chain activities in the two regions and exploit the immense potential to ensure mutual economic gains.

The potential benefit from participating in trade deals involving members of the Indo-Pacific is examined in Table 4 through a welfare analysis of four hypothetical trade agreements using a Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model, conducted by Rahman et al (2020). The model provides explanations for two kinds of economic integration: complete tariff elimination; and tariff elimination along with trade facilitation as defined by a 25-percent reduction in non-tariff barriers to trade. The four different scenarios of trade agreements are depicted in the table.

Table 4: Trade Agreement Scenarios

| Scenario |

Members of the Trade Agreement |

EU’s loss due to non- participation under situation ‘a’ |

EU’s loss due to non-participation under situation ‘b’ |

| Indo-Pacific 1 |

USA, Japan, India and Australia |

US$ 1 billion |

US$ 15 billion |

| Indo-Pacific 2 |

Indo-Pacific 1, South Asia, Southeast Asia |

US$ 24 billion |

US$ 36 billion |

| Indo-Pacific 3 |

CPTPP, India, South Korea, China |

US$ 3 billion |

US$ 19 billion |

| Indo-Pacific 4 |

Indo-Pacific 1, ASEAN, New Zealand, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, China, South Korea, Kenya, Oman, Tanzania, Mozambique, South Africa, Mauritius, Russia, Chile, Mexico, Canada |

US$ 10 billion |

US$ 102 billion |

Source: Rahman et.al. (2020)[51]

Under both alternatives, ‘a’ and ‘b’, the members stand to gain from participating in the deals while non-members would lose. The gains are higher in case of the combined situation of tariff elimination and 25-percent trade facilitation. The model did not analyse the impact of countries from the EU being part of these trade agreements, but it did estimate the welfare loss of being excluded from such a deal. For example, among the four scenarios, Indo-Pacific 2 is of particular importance especially in the context of the creation of a trade bloc without China. Under such a scenario, the loss of welfare for the EU is estimated to be around US$ 36 billion when there is tariff elimination and 25-percent trade facilitation measures in place. At the same time, under Indo-Pacific 3, comprising countries from the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)—[c] India, South Korea and China—the welfare loss for the EU is estimated at around US$ 19 billion. EU stands to lose less from not being a member of Indo-Pacific 3 as compared to Indo-Pacific 2 primarily because the US is also left out of the trade deal under Indo-Pacific 3. This suggests that the US is a significant trading partner for the EU, and US trade diversion towards the Indo-Pacific members, under Indo-Pacific 2, would hurt the EU significantly.

However, the loss for the EU is significantly higher if a trade deal is signed between members of Indo-Pacific 4. The total welfare loss for the EU is estimated to be US$ 102 billion in this case. Though a trade deal of this sort is less likely to occur due to tensions between certain member states such as India-Pakistan and China-US. Except for an Indo-Pacific 4 trade deal, the EU stands to lose the most if a trade agreement is reached between the Quad, ASEAN and South Asian countries (Indo-Pacific 2). Therefore, if EU could be integrated into Indo-Pacific 2, the welfare gains could be enormous for a significant share of the global economy. This would, however, require the US to reverse the protectionist stance towards trade agreements taken by the Trump administration. President Biden is more likely to do so than his predecessor. If the signing of the executive order to re-enter the US into the Paris climate agreement is an indication of US approval of multilateralism, then the future looks relatively more stable for the multilateral trading system under the Biden administration.[52],[53] Therefore, economic rationale favours the formation of a mega trade bloc comprising the EU, Quad, and ASEAN countries.

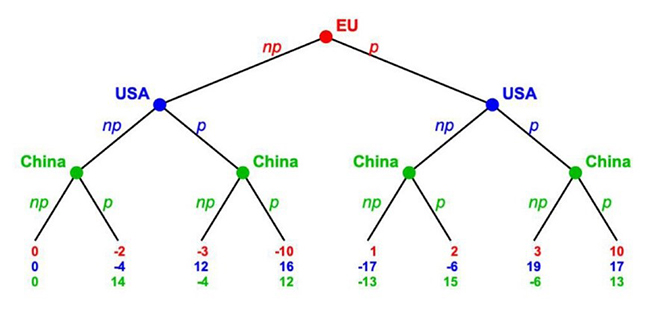

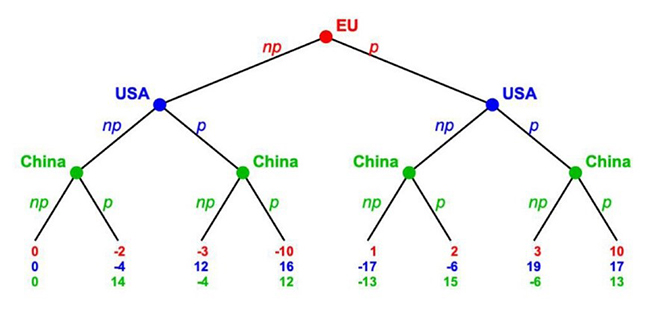

The EU’s decision to engage in deeper trade integration with the Indo-Pacific is therefore highly strategic in nature. This is represented in Figure 5 as a simplified framework of static games of complete information where the pay-offs are not zero-sum, i.e. a country’s gain is not necessarily another’s loss. These pay-offs have been determined based on the estimation of the welfare gains (or losses) through an appropriate methodology.[d] The pay-offs can be read as (EU, US, China); and they are ordinal in nature. The pay-offs should not be interpreted as absolute gains or losses as they are intended to convey the relative order of preferences.

The game consists of three players—the EU, US, and China—and they are trying to decide whether or not to participate in a trade deal with the Indo-Pacific members. Each player decides their move at the same time, but they know the pay-offs of the different countries. They can either participate (p) or not participate (np). They choose their best response function based on the strategies of the other countries. The trade preference patterns of the countries can be defined as:

For China, the EU is a preferred partner compared to the US (P1);

For the US, the EU is a preferred partner compared to China (P2);

For the EU, the US is a preferred partner compared to China (P3).

The trade preference patterns are based on the duties faced on exports to partner countries as depicted in Table 5. The share of EU exports that are imported duty-free is higher in the US as compared to China; and the simple and weighted average tariff is also lower for the US. Similarly, US exports to the EU face lower tariffs than Chinese exports; and 67.6 percent of US non-agricultural exports by value are imported duty-free as compared to only 33.8 percent of Chinese exports into the EU. These validate the aforementioned trade preference patterns for the EU and US. For China, however, the tariff rates on EU and US imports are almost the same. However, given the recent spike in EU-China trade, China has emerged as the largest trading partner of the EU and has also signed an investment deal with the EU.[54]

Table 5: Preference patterns based on duties faced on non-agricultural exports to partner countries[e]

| Duties faced on non-agricultural exports to partner countries |

| European Union |

|

|

Most Favoured Nation (MFN) 11 Average of traded tariff lines |

| Partner |

Duty free imports (% of total value) |

Simple |

Weighted |

| USA |

59.6 |

4 |

1.5 |

| China |

17.4 |

8.7 |

7.4 |

| United States |

|

|

MFN Average of traded tariff lines |

| Partner |

Duty free imports (% of total value) |

Simple |

Weighted |

| EU |

67.6 |

4.6 |

1.3 |

| China |

33.8 |

8.6 |

5.3 |

| China |

|

|

MFN Average of traded tariff lines |

| Partner |

Duty free imports (% of total value) |

Simple |

Weighted |

| EU |

47.5 |

4.6 |

2.9 |

| USA |

57.6 |

4.1 |

2.7 |

Source: World Tariff Profiles 2020, WTO, ITC and UNCTAD[55]

These preference patterns are depicted in the various pay-offs that the countries would receive (or else, forego) in the event of a trade deal (or not) with the Indo-Pacific countries in Figure 5. As depicted, the loss for EU is the highest if it does not participate, particularly in the situation where the US and China both participate in a trade deal with the Indo-Pacific countries. But even then the loss for the EU (-3) would be higher when the US participates, as shown by the pay-off matrix (-3, 12, -4) and thus in agreement with P2. In contrast, if the US did not participate, the EU’s loss would be only -2 as shown by the pay-off matrix (-2, -4, 14). At the same time, if the EU participated, and so did the US, its pay-offs would be higher irrespective of whether China participated (3, 19, -6) or not (10, 17 13), i.e. P3. However, the pay-offs for the EU is the highest if it participates (and also lowest if it does not) when both China and the US participate. This highest payoff set (10,17,13) is the Nash Equilibrium[f] of this game, because none of the countries have an incentive to deviate from this choice set (given the strategy of the other countries).This could be because the trade creation effects are going to be higher when both the US and China are part of the agreement than the trade diversion effects.

Figure 5: Extensive form of the EU-US-China trade strategy with IP

Source: Authors’ own based on estimates from Rahman et. al. (2020)

However, there are political economy factors that may hinder the creation of such a trade bloc. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the risks associated with supply-chain vulnerabilities. Therefore, if the EU is looking towards the Indo-Pacific countries as alternative sources of intermediate imports, it must examine the potential of a trade agreement without China. As depicted in the strategic game, this would generate pay-offs represented by (1, -17, -13) and (3, 19, -6). The former is when the US also does not participate and therefore the EU incurs larger losses. Gains for the EU are, however, higher when the US, but not China, is part of the agreement (3, 19, -6). Therefore, an optimal EU trade strategy to counter the growing influence of China in global trade would be to engage in a trade deal with the Indo-Pacific, along with the United States. This is also rational from the US’s point of view because it receives the highest pay-off when the EU and US participate in a trade deal with the Indo-Pacific countries.

Furthermore, between the US and China, the non-member party stands to lose whenever the other two players form a trade agreement with the Indo-Pacific. And both lose when they do not participate. The fact that China prefers the EU over US (P1) is depicted by the higher pay-off (15) it receives when it participates in a deal involving the EU but not US, as compared to the pay-off (13) when both US and EU participate.

The above analysis suggests an estimate of what the EU stands to lose, economically, if it does not participate and engage with the Indo-Pacific region. The EU already has Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) in place with Indo-Pacific countries like Japan (2019), South Korea (2011), Singapore (2019) and Vietnam (2020).[56] If intra-EU trade is excluded, its external foreign trade still accounts for around 15 percent of world trade, which puts the EU ahead of both China and the US.[57] However, it must navigate the contours of protectionism that have seen an upsurge in recent times.

EU trade policy in a changing world

International trade policy over the last five years has been characterised by a shift away from economic theory, empirical foundations and mutual cooperation, towards isolated, inward-looking geopolitics.[58] An EU trade policy aimed at integration with value-chains in the Indo-Pacific must take into consideration the animosity in US-China and India-China trade. It must also navigate the growing wave of anti-globalisation from different corners of the world, especially the exit of the UK from the European Union (or ‘Brexit’). As already highlighted in an earlier section, the growing potential in the Indo-Pacific region might be EU’s way out of its Chinese reliance. This is even more relevant for a post-COVID-19 international trade order that must focus on supply chain resilience.

An obstacle for the EU in forging a trade deal involving the Indo-Pacific and the Quad countries would be reviving its own relations with the US. The benefits of a trade agreement involving the countries from ASEAN (US$ 80 billion), South Asia (US$ 12 billion) and the Quad (US$ 317 billion) have been estimated by Rahman et. al., (2020).[59] The EU stands to lose around US$ 36 billion from being a non-member of this trade agreement, as already highlighted earlier.[60] Therefore, it is in the interest of the EU to reconstruct ties with the US and try to negotiate a trade deal involving these countries. However, EU trade policy will also have to navigate the consequences of Brexit. Although a trade and cooperation agreement has been signed between the EU and the UK, the flow of goods between the two economies will certainly be costlier than it was earlier.[61]

Furthermore, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement between the ASEAN countries and China, South Korea, Japan, Australia and New Zealand, will shift the pendulum towards manufacturing in Asia; Chinese dominance will only intensify, and could force the EU and the US to regroup on China.[62] These factors only strengthen the political significance of an EU trade policy directed at deeper integration with the Indo-Pacific region. This would also appear politically favourable to another key player in the region—India. It withdrew from the RCEP in 2019 due to concerns over Chinese imports flooding its domestic markets and widening the already existing trade deficit. Given the overemphasis by the Indian government on trade deficits, an EU-India trade deal would suit the political motives as well given that India runs a trade surplus with the EU.[63]

In this context, it is of paramount significance that the advantages of trade on welfare gains are made more visible and real to the citizens. This will require empirical research and knowledge sharing of such exercises with the other party in an agreement. Albeit difficult to master, these are a necessity to avoid the resurgence of protectionism and isolationism.

The alignment between political and economic rationale is a necessary condition for an EU-Indo Pacific trade and cooperation agreement. However, this is a challenge for the EU leadership at the moment due to forces like Brexit, as well as the EU-US and EU-China trade dynamics, all creating a complex political environment. Despite the economic benefits from the trade agreement, the political dividends must be equally lucrative.

Integrating Politics and Economics: Forging Constructive Partnerships

As the three prominent powers in the EU, France, Germany, and the Netherlands play specific roles in the European Commission’s engagements in the Indo-Pacific. These three countries have already released their Indo-Pacific policies and the UK has announced a “tilt” towards the region. Besides these countries, those in central and eastern Europe are also inclined towards accepting and expanding upon the general guidelines of cooperation that the EU has laid out. Many countries in the EU bloc also perceive India as a favourable partner for furthering ties.

In 2016, France happened to be the first EU member to declare its stance in the official document France and Security in the Asia-Pacific, followed by the publication of France and Security in the Indo-Pacific in 2019. It claims to be the resident power in the region by virtue of the island territories that it possesses and the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) derived from them.[64] With an already diverse portfolio of engagement activities in the Indo-Pacific, France is arguably the clear choice to lead in terms of deepening the EU’s involvement in the region. The term ‘Indo-Pacific’ was inducted into French foreign policy in 2018. There are, however, divergences between the US or Japanese interpretations and that of France: the latter is primarily limited to French position in international politics and the protection of the country’s overseas territories.[65] France has both overseas departments and territories and controls nearly 9 million sq km of EEZs in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, where it stations close to 5,000 permanent troops. In the southern Indian Ocean, the country’s territories include the islands of Mayotte and La Réunion, the Scattered Islands, and the French Southern and Antarctic Territories; in the Pacific Ocean, its territories comprise New Caledonia, Wallis and Futuna, French Polynesia, and Clipperton Island.[66]

France also has strategic alliances with Japan, India and Australia. The country keeps a sizeable military presence in the Indo-Pacific, maintains a network defence attachés, supports maritime surveillance, and complements the efforts of regional Information Fusion Centres, besides participating in multilateral and bilateral military, naval and air force exercises.[67] The key security concerns of France in the Indo-Pacific[68] include North Korea’s nuclear programme, land reclamation and resultant militarisation in the South China Sea, terrorism, cybersecurity, and novel forms of conflict that could intensify inter-state rivalry in the region. Therefore, led by France, the EU is poised to more extensively engage in naval diplomacy and further maritime security cooperation. In addition to its security commitments, France also participates in efforts towards environmental risk mapping, regulation of global commons, and the strengthening of cybersecurity policies.

Germany, too, adopted guidelines for its involvement in the Indo-Pacific in 2020, envisioning itself as an active partner in the region. Berlin views the Indo-Pacific as the area covering the Indian and Pacific Oceans and its guidelines are designed to provide it with entry-points for closer collaboration with countries in the region.[69] The interests of Berlin include security, diversification of relations, free and open shipping routes, free trade, expansion of ties with regional institutions, digital connectivity, and enhanced communication channels. Given the close ties of Beijing and Berlin, Germany’s guidelines have been criticised as being cautious with respect to China. Nonetheless, the very existence of the document implies the direction in which the country wants to steer its role in the Indo-Pacific.

The Dutch approach towards the Indo-Pacific, meanwhile, is laid out in the government’s “Guidelines for strengthening Dutch and EU cooperation with partners in Asia”[70] which underscore principles of democracy, multilateralism, and the preservation of the international legal order. The guidelines emphasise cooperation in areas of global concern such as climate change, human rights, and migration. The region is the biggest export market for the Netherlands outside Europe. Interestingly, the Dutch guidelines recognise the difficult position of many Southeast Asian countries who find themselves caught in the geopolitical shifts between China and countries like the US, Japan and Australia. Accordingly, the Netherlands would like its engagements in the region to be founded on shared values and proactive partnerships which are wider in their outlook than merely strategically oriented collaborations.[71] It also emphasises on working towards a common EU vision of the Indo-Pacific.

In addition to institutional and bilateral modes of cooperation, the Indo-Pacific region is also witnessing the mushrooming of minilateral forums of cooperation in various combinations. Although the efficacy of these groupings in terms of achieving concrete outcomes remains unclear,[72] being smaller in size and scope as compared to multilateral forums, minilateral platforms have the advantage of being more flexible, more focused and by extension, more functional.[73] In addition to the Quadrilateral Dialogue which has recently found renewed vigour, there are already several minilaterals in the Indo-Pacific such as the Japan-US-India trilateral (since 2010), the Australia-Japan-India trilateral (since 2015) and the India-Australia-Indonesia trilateral (since 2017). The rise of minilaterals in the Indo-Pacific is also an extension of the bilateral post-war networks of extended deterrence and containment[74] developed by the US and which in the present context seek to preserve partnerships among countries with shared goals.

Among the most recent forums is the India, France, and Australia trilateral, which held its first meeting in September 2020 and discussed economic and geostrategic challenges and cooperation in the Indo-Pacific via regional institutional mechanisms such as the ASEAN, Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and the Indian Ocean Commission.[75] Minilateral platforms offer a practical format for the engagement of EU member countries at the individual level with those in the Indo-Pacific. Another viable grouping for collaboration would be partnering with the Quad. The latter has over the past few years displayed intent and willingness to revive what had become a near-dormant grouping and is also working towards formalising its functioning. The EU already has constructive ties with individual Quad members (Japan, Australia, India and the US) and thus, partnership with the grouping in offering alternative frameworks of regional connectivity, furthering maritime security, contesting influence operations, and coordination over 5G infrastructure.[76]

Conclusion

The EU is today in a position where it is more unequivocal about its willingness to engage with the countries of the Indo-Pacific region. However, both as a Union and as sovereign countries, the EU should better define its ambit and nature of collaboration. In some ways, the Strategy document is an expression of interest; it is, however, lacking in specifics with respect to resources and capabilities that can be deployed.[77] This is because there is no clarity yet with respect to the sectors and cooperation mechanisms via which the EU would be looking to expand and deepen ties with countries in the Indo-Pacific. However, this does not dilute the purpose and intent of the EU’s involvement in the region, but rather is an indication that of the intent to leverage on areas where the EU is already engaged in (e.g., development cooperation, climate change, and disaster risk reduction) alongside specific sectors of collaboration which will be devised going forward under the broad strategic and economic cooperation framework as laid out by the Strategy document. In a region where there is already a wide scope and depth of engagement with the US, the extent of EU involvement will also be measured against its deliverables. Given the limited extent of security cooperation that the EU can be engaged in, the significance of developing partnerships in areas such as trade, infrastructure, technology and climate would hold greater potential.

The impact of bilateral ties and economic dependencies of individual countries in both the EU and the Indo-Pacific would stand to impact the effectiveness of the former’s role in the region. As discussed in the preceding sections of this paper, while the genesis of any adverse impact will be economic, the extent and strength of EU’s role will be ascertained from the political fallout of the same. A more realistic format of engagement in the coming years is likely to be a mix of institutional engagement is some sectors, together with functional agenda-based cooperation at the bilateral or trilateral levels. And while the implications of geopolitical developments will continue to underpin the cooperation mechanisms of the EU with countries in the Indo-Pacific, the involvement of the EU across tiered levels of cooperation holds potential.

About the Authors

Pratnashree Basu is an Associate Fellow at ORF Kolkata, in the Strategic Studies Programme.

Roshan Saha is a Doctoral Candidate at the Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology, Auburn University, US.

Soumya Bhowmick is an Associate Fellow at ORF Kolkata, in the Economy and Growth Programme.

(Additional research by Meghna Laha at the Department of Economics, Jadavpur University, Kolkata.)

Appendix A1. Determination of pay-offs under various trade agreement scenarios

Table A1.1

| Welfare gain/loss (in US Billion Dollars) |

|

Scenario a |

|

IP1 |

IP2 |

IP3 |

IP4 |

| EU |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

-10 |

| China |

-1 |

-4 |

5 |

10 |

| US |

3 |

3 |

-5 |

10* |

|

Scenario b |

|

IP1 |

IP2 |

IP3 |

IP4 |

| EU |

-15 |

-36 |

-19 |

-102 |

| China |

-18 |

-42 |

140 |

131 |

| US |

85 |

126 |

-39 |

177* |

| Source: Rahman et. al. (2020) |

| * refers to the average value of the total gains by members of IP1 |

Based on the above welfare gains/losses as estimated by Rahman et. al., (2020), we have arrived at the pay-offs for the EU-US-China trade with IP countries as depicted in figure 5. The different Indo-Pacific trade scenarios indicate the participation of the US and China. Irrespective of whether we consider scenario ‘a’ or scenario ‘b’, ordering of the gains/losses for the three countries remains the same. Only the magnitude varies. These estimates, along with the assumption of trade preferences between the EU, US and China as defined by the tariff profiles, have helped in arriving at the pay-offs depicted in the figure 5 in the paper. Furthermore, the following table A1.2 depicts the involvement of the US and China under the alternate trade scenarios.

Table A1.2

| Trade deal |

Involvement of US and China |

| IP1 |

only USA |

| IP2 |

only USA |

| IP3 |

only China |

| IP4 |

Both USA and China |

Source: Based on Rahman et. al., (2020)

There are 8 possible strategies (2 strategies for each player: 2 x 2 x 2 = 8) and the pay-offs are as follows. It is necessary to point out that these pay-offs are ordinal in nature and do not reflect actual magnitudes, and are mostly scaled-down from their original estimates for mathematical convenience (they are based on the estimates in table A1.1). The strategies are numerically ordered (S1 to S8) from left to right in the game-tree in figure 5.

S1: None of them participate and so the pay-offs are 0 for each one of them.

S2: Only China participates, i.e. IP 3. Here, both EU and US stand to lose. But the loss for the US and EU will be less because they prefer to be partners according to P2 and P3. Since they are both out of the trade deal, the trade diversion effects will be lesser for them. Thus, the loss for the EU is -2 and the same for US is -4. This is slightly less than the ones estimated by Rahman et al (2020) under IP3 in scenario ‘a’. However, the gain for China is 14 (derived from the gain of 140 US billion dollars under IP 3).

S3: Only US participates, i.e. IP 1 or IP 2. Since the EU is the preferred trade partner for the US (P2), the gains for the US from participating in the trade deal with the IP countries will be less than under the situation when the EU also participate, i.e. 12 (based on the estimate of 126 US billion dollars). At the same time, the loss for the EU will be higher than when the US also did not participate (i.e. S2). Therefore, the loss for EU is -3 (which is more than -2 in S2). And the loss for China will be less than under the situation when the US and EU are part of the deal but China isn’t (S7). According to the estimates in table A1.1 China stands to lose -4 under IP2.

S4: Both China and US participate, but EU does not, i.e. IP 4. Here, too, the US and China gain from the trade deal with the Indo-Pacific countries. But their gains will be less than the situation when the EU was also a part of the deal because according to P1 and P2 the EU is a favoured trading partner for the both the US and China. Thus, the loss for EU is -10 while the gains for the US and China are 16 and 12, respectively. This is deliberately assigned a value lesser than 17 and 13 (based on the estimates of 177 and 131 US billion dollars by Rahman et al 2020), respectively, to represent the preference patterns of the two countries – P1 and P2.

S5: Only EU participates, i.e. This is exactly the opposite of the IP 4 scenario. The loss for the US and China is therefore -17 and -13. But the gain for the EU is definitely more than the scenario when no one participates i.e. S1. Therefore, EU’s pay-off is 1.

S6: EU and China participate, but not US, i.e. a modified IP3. Here the gain for the EU will be more than S5, but less than when the US is also a part of the deal because of P3 and therefore the pay-off of 2. For China, the gains are more than what it would have got under S2 because China prefers a trade deal that involves the EU according to P1. Therefore, the pay-off for China is 15 (greater than the payoffs in S4 and S8 when the US is also a part of the deal). And the US will experience a loss, but this loss will be greater than what it experienced when the EU wasn’t part of a trade deal involving the IP and China, i.e. S2. Therefore, US will have a pay-off of -6.

S7: EU and US participate, but not China. This is similar to S3. Here, the EU and the US gain but China losses. Additionally, China’s loss is greater than that under S3 because it prefers the EU as a trade partner but is unable to strike a deal. Thus China’s pay-off is -6 which is more than the loss it would experience under S3. According to P2, the US prefers EU over China, and we know that the current Sino-US tariff wars have increased the costs of US-China trade. Thus, the US stands to gain the most if it forms a trade deal that avoids China but includes the other major economies. And thus we assume that the pay-off for the US will be greater than under a situation that also involves China. The pay-off for the US under trade deal involving all the countries is 17, so we assign a pay-off of 19 for the US under S7.

S8: All countries participate, i.e. IP4. The estimated gains are already defined in table A1.1. We assign payoffs based on these estimates for the three countries as (10, 17, 13).

Endnotes

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

Source:

Source:

PREV

PREV