Introduction

China’s ‘three warfares’ strategy (TWS) is critical to its military strategy against India and beyond. The TWS will likely be effective in securing gains against states with which China has contested land frontiers and states in regions where it has no territorial disputes. For instance, Beijing is increasingly making territorial encroachments in areas such as the Arctic and Antarctica, where it is not a party to any dispute.

The TWS ties in with China’s overall strategy, which is based on cost, efficiency, and cumulative long-term payoffs. China’s continued refusal to vacate at least two key areas it occupied in April-May 2020[a] demonstrates the success of the TWS in making gains at low cost. The growth of Chinese power has facilitated China’s actions in Ladakh and the polar regions. As power grows, it generates new goals, interests, and opportunities for tremendous and near-great powers.[1] The TWS is aligned with the Chinese strategic tradition of being calculative and patient and exploiting opportunities to secure gains with the least resistance from opponents and low exertion on China’s part. The expansion of Chinese power has further reinforced and enabled these elements.

The origins of the TWS are rooted in ancient Chinese strategy, with its most fundamental tenet conforming to Sun Tzu’s proclamations that “the skillful leader subdues the enemy’s troops without any fighting”[2] and that “All warfare is based on deception.”[3] The TWS ensures this while guaranteeing efficiency by keeping costs low. It plays a crucial role in shaping the information environment in the run-up to and the conduct of an operation or mission.[4] The modern TWS concept can be traced to the 1999 book Unrestricted Warfare, published by two researchers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).[b],[5],[6] By 2002, the PLA’s position had evolved, and the TWS was expanded to cover legal, psychological, and media warfare.[7]

Assessing Chinese conduct highlights that deception and efficiency are central to the TWS and has motivated the US to demonstrate considerable urgency in preventing the seizure of territory in the Arctic. The US military has deployed forces for multidomain operations in Alaska, which connects to the Arctic. This deployment is part of a more significant effort to counter Russia's and China's attempts to establish a territorial and military presence in the Arctic. Antarctica is also another likely zone for strategic competition. China’s actions in Ladakh and the Sino-Indian border are harbingers of territorial seizures in Antarctica, which is ripe for ‘salami slicing’.[c] This issue is particularly relevant because China’s use of military power for land-based threats is often ignored in favour of its maritime expansion and naval threats in the Indo-Pacific. Antarctica is attractive because it lends itself to salami slicing and more significant territorial seizures through sufficient military means, with a distinct possibility of little to no resistance.

Despite China’s tenuous attempts to consolidate its position at sea, its artificial islands in the South China Sea (SCS) remain vulnerable to attack and would be ripe targets, especially from rival navies such as the US.[8] China’s attempts to consolidate its hold on the sea and control the movement of shipping through the SCS and the East China Sea are challenging due to Beijing’s adoption of an anti-access/area denial strategy, which aims to achieve sea denial and sea control by pushing the US and allied navies away from its shores.[9] Therefore, China’s growing navy and contentious maritime claims are attracting much attention.

This paper analyses how the TWS has been applied in Ladakh to seize territory. Further, it examines the potential application of the TWS in the Arctic and Antarctica, which the US Army appears to be alert to or preparing to tackle. The TWS lends itself to territorial salami slicing, achieving fait accomplis with greater ease. Fait accomplis involves using military power to seize contested territory without precipitating war and allowing the attacking state to make a “unilateral gain” without evoking a retaliatory response from the defender to undo that gain.[10] Consequently, fait accomplis are implemented in increments and tend to be decisive. Thus, the TWS has broader implications beyond India’s experience in Ladakh and the Sino-Indian boundary.

Understanding China’s ‘Three Warfares’

From a military standpoint, the TWS aims for information supremacy—or information warfare—making it critical to successful military outcomes.[11] Information warfare prioritises gaining a first-mover advantage to secure an objective.[12] While the TWS is fundamentally a derivative of Chinese strategic culture, which places a high premium on deception and efficiency, in its contemporary form, it is derived from the lessons that China has drawn from American military campaigns such as the first Gulf War (1991) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization-led military campaign against Kosovo (1999).[13] It is most, if not exclusively, effective in the pre-kinetic stage of a military operation or mission in that it does not involve or require the physical destruction[14] of enemy capabilities, command-and-control nodes, and military infrastructure. Instead, the TWS entails psychological warfare, media or public opinion warfare, and legal warfare. Therefore, the TWS is not exclusively concerned with traditional warfighting but is aligned towards aiding Chinese diplomacy and influencing adversaries’ decision-making.[15]

Psychological warfare involves influencing the cognitive dimension of the enemy’s perceptions, emotional state, will, and behavioural conduct[16] to impact the enemy’s ability to resist. The psychological element is directed at achieving “...greatest victory at the smallest cost”.[17] Public opinion warfare is communications-based (through the media). In a confrontation, both sides use various media, such as television, radio, print, and the internet, to relay information. Communicating through these media platforms is an informationised strategy that involves putting out “select information in a planned and purposeful manner”.[18] This also entails the imperative of preserving cohesion in public opinion by ensuring the ideological unity of civilians and the military and ensuring primacy and equivalence by dividing and fragmenting the enemy’s public opinion and unity.[19] Legal warfare involves domestic and international law that both parties to a confrontation are subjected to. Exposing and criticising the illegal conduct of the enemy serves to position a country in a legally advantageous way and enables a flexible interpretation of treaty-based or bilaterally concluded agreements.[20] Chinese domestic laws, such as the Anti-Secession Law,[d] serve as instruments of coercion and justification for military action.[21] This can also involve convoluted and unreasonable legal positions in international disputes or in cases where sovereignty is contested.[22]

All three tenets of the TWS are “complementary” and “mutually reinforcing”,[23] but deception and diplomatic alignments with friendly states play an integral part, without which the TWS would be ineffective. For instance, psychological warfare reinforces or complements public opinion warfare by purveying select information geared towards shaping public perceptions—not just at home, but equally, and more consequentially, for the adversary—to align them with China’s goals.[24] Demoralising and manipulating the adversary’s citizens is essential,[25] such as making the enemy public believe that Chinese claims are legitimate and should be respected. While each tenet of the TWS may be independently effective and assume salience in specific situations, they are generally seen as complementary.[26] Public opinion and legal warfare are consequential at the strategic level, whereas psychological warfare assumes prominence at the operational and tactical levels.[27] Thus, the TWS is a form of non-kinetic warfare.[28]

The ‘Three Warfares’ Strategy and Ladakh

China has already given a glimpse into how the cyber or digital domain might play out in a Sino-Indian military confrontation. In the run-up to the PLA Army’s occupation of India-claimed territory in April-May 2020, China’s internet media gave little indication of Beijing’s angst against New Delhi for revoking Article 370, which conferred special autonomous status to Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), other than officially and publicly expressing displeasure with New Delhi’s decision.[29] Even the Indian home minister’s statement that Aksai Chin—which was under Chinese control even before the current boundary crisis—belonged to India did not evoke a strong response. After the revocation of Article 370, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited India in October 2019 as part of a second informal summit hosted by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The first of the two informal summits was hosted by Xi in 2018. Although the summitry between Xi and Modi may have concealed the motives of the former, and the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic was a key distraction preventing the Indian Army’s response, few considered the recondite role of the cyber domain, which is intrinsically deceptive.[30] Besides television and radio, the internet is a vital source of information for assessing Chinese attitudes and views. It is also likely the primary open-source medium for Indian analysts on China, especially those outside the government, to gauge that the tension and ongoing crisis on the Line of Actual Control (LAC) between India and China is overshadowed by the competition over development.[31] Those within the government also rely on open-source and secret intelligence for their analyses. Indian intelligence did not pick up communication intercepts about the possibility of Chinese military action that culminated in the seizure of Indian territory in eastern Ladakh.[32] Indeed, Xi even invited Modi for a third informal summit, which Modi accepted, thus indicating no dissatisfaction or displeasure with India.[33] In the months leading up to the PLA’s aggression in eastern Ladakh, there was no sign from within China of increasing hostility over New Delhi’s decision besides the Chinese foreign ministry’s criticism of the altered status of J&K. Explanations of Chinese conduct being a byproduct of India’s J&K decision are post-hoc justification and rationalisation of Chinese motives.[34] According to former Indian National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon, it would be misleading to blame the Modi government’s decision to revoke the administrative status of J&K as a proximate cause of Chinese military action to occupy territory in eastern Ladakh.[35] During Xi’s subsequent visit to India for the 2019 informal summit at Mamallapuram, the Chinese leader neither expressed any objections or concerns about J&K’s special status being revoked nor did the Chinese government or official media drop any hints of the matter being raised. Other factors likely contributed to China’s aggression in eastern Ladakh.[36]

This pre-attack deception can—and should—be viewed as a form of disinformation and is integral to China’s information warfare and military strategy. China’s suppression of any acute dissatisfaction with the Indian government’s J&K decision was fundamentally a misinformation or disinformation campaign. This was reinforced by Xi’s acceptance of Modi’s invitation to the 2019 second informal summit, which seemingly reflected diplomatic conciliation and concealed operational-military intent in the run-up to the PLA’s seizure of territory in eastern Ladakh. On the violation of the status quo due to China’s territorial seizure, Hua Chunying, China’s foreign ministry spokesperson, dismissed the notion that China’s actions triggered a war.[37] She further asserted that Beijing did not occupy the territory of another country, noting that Chinese forces did not cross the LAC, and blamed the misunderstanding and confusion on poor communication between New Delhi and Beijing.[38] Beijing considers that the triteness and obfuscation underpinning the PLA’s “informationisation” strategy create opportunities to synthesise all three elements of the TWS.[39]

Thus, the 2019 informal summit should be construed as a stratagem to reflect an apparent “stability” in the Sino-Indian relationship despite the change in J&K’s status. This was coupled with China’s domestic suppression of any hostile commentary through the digital medium, which served to deny information to Indian decision-makers and intelligence. This allowed the Chinese to combine their annual combat exercise near the LAC into an attack without resistance. A confluence of diplomatic and digital feints and China’s exploitation of the legal ambiguity undergirding the LAC helped the PLA make some key tactical territorial gains. Thus, China effectively applied the TWS against India. As one expert observed, using “propaganda to influence public opinion can reinforce the stratagem of ‘making a feint in the east to attack in the west’”.[40] Indeed, China pulled off the feint against India in Ladakh, which is on China’s western flanks, despite their primary aim being located in the east, in the forcible integration of Taiwan. Beijing’s territorial claims have also historically focused on the eastern sector of the Sino-Indian boundary, which consists of the Tawang Tract (or what China calls Southern Tibet), comprising all of Arunachal Pradesh,[41] and not in the west, which consists of Ladakh and Aksai Chin. The PLA’s military action in the West rather than the better-defended East helped the Chinese state shape public opinion and reiterated the importance of disinformation for effective deception.

Notwithstanding India’s stance, China will persist in its efforts to keep engagements below the threshold of full-blown armed conflict and avoid using heavy weapons, in keeping with the TWS. However, India would have to remain alert to the possibilities of salami slicing via the TWS and a larger military offensive.[42] Currently, the TWS is the most efficient strategy for Beijing because it keeps costs low and generates cumulative long-term payoffs. As part of the TWS public opinion warfare, the digital medium has played a vital role in enabling the occupation of key areas in Ladakh. It is also a textbook case of how the TWS is implemented to seize territory through deception, subterfuge, and concealment. But the applicability of the TWS extends beyond Ladakh to the Arctic, where China has made similar, if not identical, claims on the territory.

China’s Claims in the Arctic Through the ‘Three Warfares’

China has adopted a two-pronged approach to its claims in the Arctic. China considers itself not just as possessing interests in the Arctic but as a “polar great power”.[43] This is central to Beijing’s Arctic strategy, which views the polar regions as a new domain of warfare alongside sea-bed, cyberspace, and space warfare.[44] Officially, China views itself geographically as a “near-Arctic country”.[45] China has engaged in subterfuge by refraining from revealing too much about its Arctic ambitions, lest it offend other Arctic states. China is driven by the quest to secure mineral resources and establish a military foothold in a highly strategic region where Russia and the US are also key actors.[e] Publicly, China aims to convey that it is a limited actor in the Arctic with highly circumscribed aims.[46] China secured observer status at the Arctic Council in 2013,[f] with some of the staunchest support coming from Norway[47] and Sweden, incidentally Beijing's principal targets of sanctions.[48] Publicly and officially, China’s aims are benign, striving for the protection of the environment, better use of resources, improved standards of living for the local population, and the establishment of new shipping routes in the Arctic—all of which will contribute to the economic and social development of the Arctic.[49] Yet, Beijing’s actions as a claimant to Arctic resources and a geographically consequential actor reflect well-crafted subterfuge. Chinese actions have progressively betrayed Beijing’s public pronouncements. For instance, while a 2018 white paper released as part of China’s Arctic policy notes that “states from outside the Arctic region do not have territorial sovereignty in the Arctic”,[50] the Chinese also treat the Arctic as part of the global commons, allowing them to act below the redline of an explicit strategic challenge to members of the Arctic Council.[51] In internal or domestic commentary, Chinese scholars and experts view the Arctic and Antarctica as zones for future strategic competition and military confrontation and make the case for China to gain a foothold in the polar regions.[52] The latter closely ties into legal warfare to the extent that Beijing will use tortuous legal justifications, which is a key tenet of the TWS or generate “legal support for operational success…informed by the principles to ‘protect national interests as the highest standard’”.[53] This includes respecting the basic principles of the law in a quest to execute legal warfare that is based on military operations, which seeks to “seize standards” and use them “flexibly” and variably.[54] It further enshrines a “legal struggle” that aims to seize the “initiative”.[55] When applied to the SCS, this has led to very devious “interpretations of international law”, as was evident during the international arbitration process that led China to oppose the Philippines’s claims and position in the SCS. In 2016, the Hague Tribunal ruled in favour of the Philippines in the case of the Spratly Islands, which are viewed as rocks or “low tide elevations” rather than islands.[56] However, as with the Mischief Reef, China dredged sand and turned the islands into military-level airstrips and port installations.[57] It also led to Beijing opposing the legitimacy of the process under the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague.[58] A similar situation could take effect in the Arctic, notwithstanding China’s denials, even if the Arctic and the SCS are not the same simply because of geographic factors, making Chinese claims and assertiveness in the former more complex than the latter[59] In addition, environmental realities in the North Pole and China not being a core member of the Arctic Council also grate against—if not render impossible—China’s capacity to establish a strong commercial and military presence in the Arctic region in the immediate future.[60] China will expansively assert its claims if it feels that its interests need to be consolidated. In the Arctic, this has manifested in China’s pursuit of benign cooperative narratives on environmental issues and multilateralism camouflaging Beijing’s more assertive and aggressive interests and goals.[61]

China’s scientific state bureaucracy dedicated to Arctic research is key in advancing the ambitions undergirding China’s geostrategic agenda.[62] China has been active in the Arctic since the late 1990s through several expeditionary missions, establishing its first research base, the Yellow River Station, on Svalbard Island in 2004.[63] China also has another research station in Iceland. Both facilities perform various functions, from marine ecology to atmospheric physics research.[64] A third Chinese facility in Sweden is clouded in controversy as it is suspected to have close ties to the PLA.[65] Notwithstanding a pushback from core members of the Arctic Council against China’s growing presence in the Arctic region, Beijing remains determined.[66] China is the junior partner to Russia in the Arctic but given the scale of its resources and the extent to which it has defined and adopted the role of a “Near Arctic State”,[67] despite its 1,800-kilometre distance from the Arctic Circle, Beijing will play an equally significant role in shaping military outcomes in the Arctic as Moscow—if not immediately, then in due course. The latest evidence suggests that China is conducting joint naval exercises with Russia near the Aleutian Islands, near Alaska.[68] This triggered the US Navy to send a flotilla of four guided missile destroyers to monitor the Sino-Russian naval exercise.[69] Chinese military analyst Fu Qianshao observed that “the Americans should get [used] to it.”[70] This statement implies that a Chinese naval presence close to Alaska will, at a minimum, be regular and, at maximum, permanent.

This latest naval exercise should come as no surprise. Since early September 2015, when the PLA Navy first deployed five vessels to the Arctic,[71] the Chinese navy has made multiple deployments, reflecting its growing naval might. The joint patrol exercise with the Russians in August 2023 foreshadows China’s naval developments in far seas, which are likely to increase complexity and pace in the coming months and years.

Russia is a vital member of the Arctic Council and seeks to consolidate existing sovereign claims and control access to the region. Among all the Arctic states, it has the most extensive coastline in the Arctic region. Despite Moscow’s initial strong opposition to Beijing’s bid for observer status to the Arctic Council,[72] Russia’s increasing dependence on China for technology and investment, especially since the war in Ukraine, has progressively enabled the latter to gain a foothold in the Arctic region.[73] Indeed, as per the US Army, “America’s great power competitors – Russia and China – have developed Arctic strategies with geopolitical goals contrary to U.S. interests. China aims to gain access to Arctic resources and sea routes to secure and bolster its military, economic, and scientific rise”.[74] More recently, Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar stated that “Russia is looking towards Asia”.[75] This is bolstered by the fact that the Arctic generates roughly 20 percent of Russia’s gross domestic product (GDP), 22 percent of its exports, and 10 percent of its total investment in Russia.[76] Russia’s economic future after the Ukraine war hinges even more on integration with Asian markets, especially China. For Beijing, Moscow is the gateway to an Arctic military presence.

Moscow has no choice but to acquiesce to Beijing’s expanding military footprint in the Arctic, albeit with great reluctance, to offset US-led Western military support for Ukraine arising from Russia and the West’s trade, finance, and technology sanctions. Indeed, colluding with China in the Arctic is a compulsion for Russia because they have a common adversary in the US.[77] Similarly, Russia faces the dilemma of balancing its ties with China and India over their boundary dispute and the ongoing Ladakh crisis. Collusion with Russia is consistent with China’s TWS and its “diplomatic struggle” to involve like-minded partners to consolidate gains. Therefore, Russia facilitates China's access to the Arctic and aligns well with China’s strategic culture and the TWS.[78] Sino-Russian Arctic cooperation has manifested in the Yamal liquid natural gas project, a joint venture between the Chinese National Petroleum Corporation and the Russian energy company Novatek. For Russia, Yamal serves the purpose of neutralising growing competition from Australia, Qatar, and the US, and showcasing that it has alternative, non-Western sources of financing for its vital energy projects.[79] In fact, 60 percent of the financing for the project originates from China.[80] For Beijing, the Northern Sea Route (NSR) along the Russian coast offers an alternative commercial maritime route to European export destinations. The NSR holds great allure for China, as Chinese maritime and commercial shipping through the Malacca Straits, the Indian Ocean, and the Suez Canal present significant naval and strategic vulnerabilities (see Map 1).

Map 1: Northern Sea Route

Source: Vitaly Yermakov and Ana Yermakova, “Northern Sea Route as Energy Bridge”. [81]

The similarities in the regions of Ladakh and the Arctic, both in terms of climatic conditions and terrain, explain why the US Army is making critical investments aimed, at a minimum, at limiting Sino-Russian collusion, and, at a maximum, at pre-empting China from gaining a significant and militarily consequential foothold in the region. The relationship between China and Russia has also impacted India from a military standpoint. New Delhi’s capacity for a military escalation in the Himalayas is limited—not for lack of will but because its dependence on resupply for its Russian-origin weapons systems is likely to be constrained as a result of Moscow being indebted to Beijing, or at least subject to the latter’s pressure against aiding India.

The US faces no resupply problem comparable to India but faces a collusive challenge from China and Russia in the Arctic. China views both poles (i.e., the Arctic and Antarctica) as regions that have “undetermined sovereignty”[82] and “ungoverned space…ripe for resource extraction,[83] and the Arctic is also a militarily consequential region for China. Diplomatic collusion with other powers, such as Russia, reduces the possibilities of kinetic and reciprocal action by China’s adversaries.[84] This is the fundamental common threat facing the US and India from China and tacit Russian collusion with China’s aims.

Beijing is eyeing the Arctic as a passage for resource exploitation, commercial shipping, and a new sea route to Europe. According to PLA Navy Rear Admiral Yin Zhuo, given the considerable resources in the deep-sea zone of the Arctic, it will constitute a strategically key shipping route in the future.[85] This is only a partial view of Chinese ambitions; China is also preparing sea-bed warfare capabilities in the Arctic.[86] Consequently, China cannot abandon the Arctic to other states because it has salient interests in the area.[87]

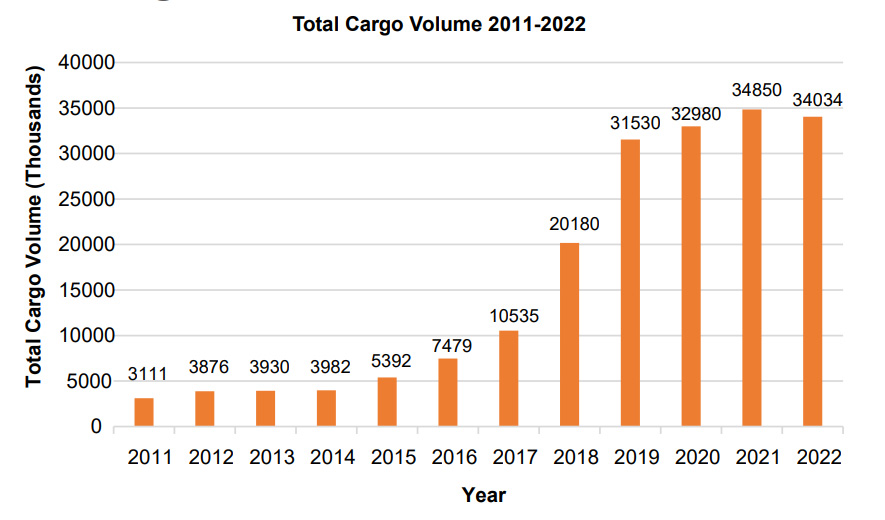

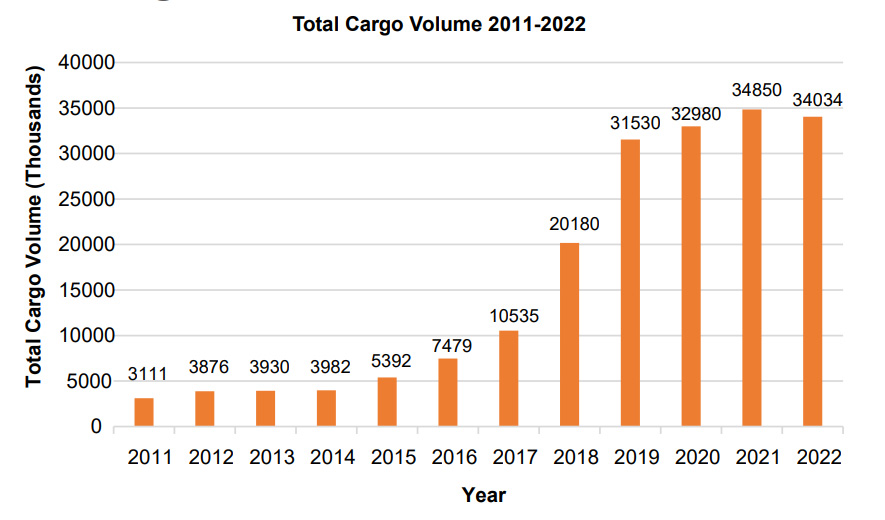

Environmental changes caused by climate change have created strategic opportunities for great powers such as China. Arctic warming, estimated to be three times higher than the global average, has created new and shorter commercial shipping routes.[88] Global warming has rendered the Arctic more navigable. Chinese researchers have concluded that navigating through the NSR would be easy when temperatures remain at or under 2 degrees Celsius and become even more accessible when temperatures increase to 3 degrees Celsius.[89] While this increase in navigability does not mean that the Arctic will supplant other shipping routes, such as the Suez Canal or Malacca Strait, the volume of freight traffic moving through the Arctic has steadily increased since 2011 (see Figure 1), except for a slight dip in the volume of cargo in 2022 compared to 2021. In addition to the new passage and decreased transit times offered by the NSR, it also signifies a growing Chinese military presence.

Figure 1: Volume of Cargo Transiting Through Northern Sea Route

Source: Shipping Traffic at the NSR 2022, Northern Sea Route Information Office [90]

China has established dual-use facilities that cater to both military and civilian needs. Such facilities are integral to China’s military-civil fusion.[91] Civil-military fusion involves using civilian facilities as a cover for military activities or a combination of both. China has conducted oceanographic surveys and acoustic modelling that reflect China’s actions in the SCS to enable its navy to operate more freely.[92] Oceanographic surveys are also crucial to sea-bed warfare. Chinese academics have identified several ports along the Russian coast of the Arctic where China can establish a presence. For instance, Chinese defence industry major China Poly Group has ploughed US$300 million into a coal terminal in Murmansk and signed an agreement to develop a deep-water port at Archangelsk.[93] Therefore, Beijing has conducted and continues to conduct military activity under the pretext of civilian activity. While all the core members of the Arctic Council have run afoul of Russia due to its invasion of Ukraine, China has made clear it will not extend recognition to the Arctic Council if Russia is denied membership or participation.[94] The growing antagonism between Western members of the Arctic Council and Russia has created opportunities for China, resulting in Beijing's creeping militarisation of the Arctic.

US military and strategic assessments have also observed increasing geopolitical competition due to converging Sino-Russian interests.[95] Consequently, the pressure on the US armed services to respond is growing due to the inherent dynamics of the Arctic region. Firstly, there is a veritable absence of large “settled populations” in the area,[96] much like in Ladakh and other parts of the Sino-Indian boundary. Secondly, governmental infrastructure and presence in the region are also limited.[97] Thirdly, the Arctic region's economic and military infrastructure is not highly robust.[98] These factors create opportunities for China to change “facts on the ground” instead of other areas.[99] Canada is the Arctic Council member with the next most significant presence in terms of land area; however, Ottawa has no military power to protect its claims in the face of China’s commercial and military activities.[100] Therefore, the US Army has been compelled to reactivate the 11th Airborne Division in Alaska.[101]

The US Army’s assessment of American military vulnerabilities in the Arctic was foreshadowed and catalysed by India’s experience with the PLA in Ladakh in 2020. While Beijing’s military foray into the Arctic is still evolving, Antarctica is witnessing a similar, if not identical, situation, but with greater opportunities for territorial annexation and control through the application of TWS.

The ‘Three Warfares’ Strategy and Antarctica

Antarctica, a continent on the South Pole, is covered by an almost permanent ice sheet. It is also a continent that has not been subjected to the same level of exploitation as other parts of the world for resources.[102] Therefore, in Antarctica, China has the most significant scope to engage in salami slicing by grabbing chunks of territory towards eventual enlarged territorial control. Out of the 12 original signatories to the Antarctic Treaty, seven were primary claimants to territory under the treaty. These include Argentina, Australia, Chile, New Zealand, France, Norway, and the UK. However, these seven members never arrived at a resolution to the question of sovereignty under the treaty's terms.[103] Uncertainties around sovereignty persist for major powers such as the US, Russia, China, India, and other signatories.[104] The treaty currently has 44 members who have acceded to a consultative status that permits them to participate in meetings.[105] Under Article IX.2, they enjoy participation in consultative meetings as long as they can show that they are “conducting substantial research activity there [Antarctica]”.[106] Of the 29 consultative parties, only 17 of the acceding states are recognised by this provision and meet it.[107] Yet, the question of sovereignty remains unresolved. This has created opportunities for China to expand its presence on the continent.

Over a decade ago, Yin stated that since China’s population accounts for one-fifth of the world’s population, the country is commensurately entitled to a fifth of the Arctic and Antarctica’s resources or at least a fifth of the interests that China has in the polar regions.[108] Given the stakes and the size of its population, China appears to want to leave no scope for other countries to step on its interests in Antarctica.[109] At the Politburo Bureau meeting in July 2013, Xi stated the imperative for polar exploration as the need to “take advantage of ocean and polar resources”.[110] Although the existence of abundant mineral resources in Antarctica is yet to be established scientifically,[111] China will likely resort to “tortuous” legal justifications to advance its ambitions and interests in the area as they have done elsewhere.[112] Resource extraction is a critical, though not exclusive, facet of China’s claims in Antarctica. Aligning China’s military foothold with resource claims in Antarctica is imperative. The extent of scientific research, research stations, and infrastructure required to conduct science-based research has become the basis for asserting sovereign territorial claims.[113] In line with the TWS, China conceives of its interests expansively, with or without resorting to legal justifications. In addition, a white paper presented by the State Oceanic Administration stated that Antarctica is “a new space of global environment and resources that is of great significance to the process of human development”.[114] The paper reiterated Xi’s position that China will “understand, protect and use [resources]”.[115]

Unlike the Arctic or the SCS, Antarctica is a continent or landed territory. Being continental, it is susceptible to PRC salami slicing, as in the case of eastern Ladakh in April-May 2020. There is also a veritable absence of large, settled populations in the region. Consequently, China’s capacity and possibilities to expand using TWS are greater in Antarctica than in the Arctic. Fait accomplis are much easier to pull off on land than at sea and can be potentially executed on a much larger scale on the Antarctic continent—not only because resistance might not be robust or limited but also because it would enable China to make low-cost gains, as recommended by the TWS. Chinese exploration of the Antarctic continent began following its accession in 1983 to the Antarctic Treaty. Antarctic Treaty members who enjoy consultative status can participate in meetings and decision-making processes (see Table 1).

Table 1: Parties to the Antarctic Treaty

| Country |

Entry Into Force |

Consultative Status |

Environment Protocol |

| Argentina |

23 June 1961 |

23 June 1961 |

14 January 1998 |

| Australia |

23 June 1961 |

23 June 1961 |

14 January 1998 |

| Belgium |

23 June 1961 |

23 June 1961 |

14 January 1998 |

| Brazil |

16 May 1975 |

27 September 1983 |

14 January 1998 |

| Bulgaria |

11 September 1978 |

5 June 1998 |

21 May 1998 |

| Chile |

23 June 1961 |

23 June 1961 |

14 January 1998 |

| China |

8 June 1983 |

7 October 1985 |

14 January 1998 |

| Chechia |

1 January 1993 (n) |

1 April 2014 |

24 September 2004 |

| Ecuador |

15 September 1987 |

19 November 1990 |

14 January 1998 |

| Finland |

15 May 1984 |

20 October 1989 |

14 January 1998 |

| France |

23 June 1961 |

23 June 1961 |

14 January 1998 |

| Germany |

5 February 1979 (n) |

3 March 1981 |

14 January 1998 |

| India |

19 August 1983 |

12 September 1983 |

14 January 1998 |

| Italy |

18 March 1981 |

5 October 1987 |

14 January 1998 |

| Japan |

23 June 1961 |

23 June 1961 |

14 January 1998 |

| South Korea |

28 November 1986 |

9 October 1989 |

14 January 1998 |

| Netherlands |

30 March 1967 (n) |

19 November 1990 |

14 January 1998 |

| New Zealand |

23 June 1961 |

23 June 1961 |

14 January 1998 |

| Norway |

23 June 1961 |

23 June 1961 |

14 January 1998 |

| Peru |

10 April 1981 |

9 October 1989 |

14 January 1998 |

| Poland |

23 June 1961 |

29 July 1977 |

14 January 1998 |

| Russia |

23 June 1961 |

23 June 1961 |

14 January 1998 |

| South Africa |

23 June 1961 |

23 June 1961 |

14 January 1998 |

| Spain |

31 March 1982 |

21 September 1988 |

14 January 1998 |

| Sweden |

24 April 1984 |

24 September 1988 |

14 January 1998 |

| Ukraine |

28 October 1992 |

4 June 2004 |

24 June 2001 |

| UK |

23 June 1961 |

23 June 1961 |

14 June 1998 |

| US |

23 June 1961 |

23 June 1961 |

14 January 1998 |

| Uruguay |

11 January 1980 |

7 October 1985 |

15 January 1998 |

Source: The Antarctic Treaty[116]

Although China is a signatory to the Antarctic Treaty, the country has continued expanding its footprint on the continent. Since joining the Treaty, China has allied with Australia, which lays claim to 42 percent of Antarctica’s territory.[117] Canberra is the most prominent sovereign claimant to much territory on the Antarctic continent. Although Canberra’s sovereign claims have not been fully contested by any of the states that are party to the Antarctic Treaty, challenges, especially over resources, may arise if more prominent state actors such as Russia, the US, China, and India do not respect Australia’s sovereign claims in the future.[118] Australia cannot militarily defend its territorial interests on the continent[119] if stronger actors press ahead with military action. Of all the major powers engaged in Antarctica, China is increasingly asserting itself on the continent. For several years, China has operated four research stations, three of which are in Australian Antarctic Territory.[g],[120],[121] A fifth research station is being constructed, the foundation of which was laid in 2018 at Ross Island, a region with abundant fauna. Although dual-use facilities involving scientific and intelligence collection activities have been undertaken by all major parties with research stations in Antarctica, expanding Chinese surveillance activities under the cover of civilian research is a growing strategic challenge to overcome.[122]

The growing Chinese presence in Antarctica, marked by the fifth facility, could bring a large part of the southern hemisphere under Chinese surveillance and reconnaissance (see Map 2).[123] Beijing has established an observatory that will surveil and gather signals intelligence (SIGINT) across Australia and New Zealand and track the telemetry information of rocket launches from Australia’s newly-built Arnhem Space Centre.[124] While China has already raised concerns among many Antarctic Treaty states, its actions should come as no surprise because the Ross Sea possesses an abundance of oil and natural gas.[125] While the fifth facility will ostensibly be used to conduct scientific research and to serve as an observatory, it will mainly perform the function of a satellite ground station.[126] This observation facility is located near McMurdo, the US’s most prominent research station in Antarctica. Although the US can monitor China’s surveillance activities, the new facility will allow Beijing to track submarines better with the help of Chinese satellites.[127] Notwithstanding Chinese claims of a scientific interest in Antarctica, its interest is primarily in an Antarctic “presence”.[128] In areas where resources are discovered or believed to exist, China is likely to pursue investments in civilian research and investing in deploying military capabilities on the continent.[129] Further, countries such as Australia have greatly facilitated, at least unwittingly, China’s growing presence in Antarctica. Consistent with the TWS, China has pursued carefully crafted diplomatic alignments, as is evident in the case of Australia, to secure gains at the cost of the cooperating state. The research stations established by China will enable it to consolidate its presence and push towards making territorial claims and asserting sovereignty.

Map 2: China’s New Station in Antarctica (Under Construction)

Source: CSIS [130]

While the Antarctic Treaty permits the presence of military personnel or equipment for scientific research for peaceful purposes on the continent, it expressly prohibits the establishment of military bases.[131] An inspection regime also requires parties to the treaty to inform each other of their activities and allow inspections of their activities by other parties.[132] However, scientific research and exploration and the exploitation of resources could also be used as a pretext for the progressive militarisation of the continent—much like China’s expansive maritime claims in the SCS, which is also home to abundant resources.[133] While China has agreed not to undertake mining and drilling in Antarctica until 2048,[134] this timeline could be significantly accelerated if the Chinese renege on their pledge; China has, after all, advanced the date of their potential seizure of Taiwan to 2027.[135] The possibility of countervailing responses by other parties to the Antarctic Treaty will induce China to make variable claims and catalyse its efforts to consolidate gains in Antarctica.

Conclusion

China’s application of the TWS is designed to achieve maximum gains at a low cost. Fait accomplis are much easier to pull off on land than at sea. In that sense, Ladakh foreshadows what will come in Antarctica and the Arctic, as indicated by the US Army’s preparations. Notwithstanding the significance of the TWS to the PLA’s intrusions and occupation of India-claimed territory in eastern Ladakh, the Galwan clashes drove home the real possibilities of escalation for China and that ‘winning without fighting’ would have clear limits. It is also the prime reason—despite the December 2022 skirmish between Indian and Chinese troops at Yangtse that resulted in severe injuries to both sides—that escalation using more potent weapons has not taken place. Ultimately, wars are a contest of arms that involve real combat and military engagements between opposing forces.[136] Therefore, the clever ruses that are integral to the TWS can never be a credible or sustainable substitute for an actual military contest, regardless of what China pulled off in eastern Ladakh.

It remains an open question whether China understands the limitations of using stratagems to secure territorial gains by salami slicing and fait accomplis, which India is now more alert to due to the nature and extent of its reciprocal military deployments along the LAC. The TWS is already being implemented beyond Ladakh and the Sino-Indian boundary, as China’s leaders see new opportunities for making low-cost gains in the Arctic and Antarctica, resulting from the clarity with which its strategic managers view their interests. Land warfare and, more generally, land power will still matter. Any large seizures of territory beyond what Beijing pulled off in Eastern Ladakh will require a significantly greater application of force by the Chinese in any sector along the Sino-Indian boundary. The latter possibility cannot be ruled out, meaning India must be doubly alert and prepare for a massive attack by the Chinese. Another implication of China’s unstated official position is that, as a populous country, it is entitled to a share of the world’s resources proportionate to its demographic weight. By this reasoning, China’s opponents, such as India, which recently surpassed it as the world’s most populous country, have the same entitlement. The difficulty with this argument is that China has the military strength to stake claims in the Arctic and Antarctica, but India does not. China’s leadership, with Xi at the helm, is also prepared to take greater risks than his predecessors. This is manifesting in India’s borders with China and the polar regions. The PLA Navy is also numerically the largest naval service in the world, with an advanced fleet that can keep the Chinese presence in Antarctica well-supplied. China has made gains in strategically vital and resource-rich areas in Antarctica. This makes it imperative for the Quad countries (India, the US, Australia, and Japan) to pool their resources and technological capacities.

The TWS has served as the mechanism by which China has maximised gains at low costs. India should work with the Quad states to devise a common diplomatic and military strategy to defeat China’s expansive and variable claims in the polar regions, especially Antarctica. Australia, a claimant to over 40 percent of the continent, cannot enforce its own claims. Therefore, it will need to work with other Quad members to stop China from staking additional claims on its Antarctic territory.

None of the Quad’s official statements mention the polar regions.[137] Therefore, discussions among the Quad partners at all levels must begin in earnest to address how to tackle China’s growing scientific and military footprint, at least in Antarctica. In due course, official statements following the Quad meetings must reflect the measures the grouping takes to tackle China’s role in Antarctica. The scope for cooperation among the Quad countries is the greatest in Antarctica. Geographic factors and China’s more evolved posture in Antarctica also give the Quad additional rationales for forging cooperation to constrain and monitor China’s presence on the continent. All the Quad countries have research stations in Antarctica. Therefore, working together to share SIGINT should be a priority for the Quad countries in Antarctica. This would require some of them, especially India (which operates the Maitri and Bharti research stations), to augment their capabilities in Antarctica.

Endnotes

[a] Depsang Bulge and Demchok.

[b] The authors clearly stated that the law had to be weaponised.

[c] ‘Salami slicing’ is steady and cumulative pressure that involves limited seizures of territory that does not evoke a robust response from the defender.

[d] The law was passed under the Hu Jintao regime in 2004 to prevent Taiwan’s secession.

[e] The Arctic Council has eight members: Norway, Canada, Sweden, Finland, Russia, the US, Denmark, and Iceland.

[f] The Artic Council observer status is open to non-Arctic countries. These are: France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, China, Poland, India, South Korea, Singapore, Spain, Switzerland, and the UK.

[g] The four research stations are the Great Wall, established in 1985 on King George Island; Zhongshan, established in 1989 on Larsemann Hill; Kunlun, established in 2009 on Dome A, close to central east Antarctica; and Taishan, established in 2014 on Princess Island.

[1] Robert J. Art, “The United States and the Rise of China: Implications for the Long Haul”, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 125, No.3 (Fall 2010), p. 361.

[2] Sun Tzu, The Art of War, (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2017), Kindle Edition.

[3] Tzu, The Art of War.

[4] Tzu, The Art of War.

[5] Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, Unrestricted Warfare, (Beijing: PLA Literature and Arts Publishing House, 1999).

[6] Lynn Kuok, “China’s Legal Diplomacy”, Survival, Vol. 65, no. 6, December 2023-January 2024, p. 160.

[7] Kuok, “China’s Legal Diplomacy”, Survival, Vol. 65, no. 6, (December 2023-January 2024), 160.

[8] This was well highlighted by one American strategic expert to this author.

[9] James Goldrick and Sudarshan Shrikhande, “Sea denial is not enough: An Australian and Indian perspective”, theinterpreter, The Lowy Institute, March 10, 2021, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/sea-denial-not-enough-australian-indian-perspective

[10] Dan Altman, “By Fait Accompli, Not Coercion: How States Wrest Territory from their Adversaries”, International Studies Quarterly, 61 (2017), 882.

[11] Vinod Anand, “Chinese Concepts and Capabilities of Information Warfare”, Strategic Analysis, Vol. 30, No. 4, (2006), 781-97.

[12] James Mulvenon and Richard H. Yang, The Peoples Liberation Army in the Information Age, (Santa Monica: RAND Corporation, 1999), 177.

[13] Sangkuk Lee, “China’s ‘Three Warfares’: Origins, Applications and Organisations”, Journal of Strategic Studies, Vol. 37, No. 2, 2014, pp. 198-221.

[14] This is a well made point by one Indian analyst, Abhijit Singh, “China’s ‘Three Warfares’ and India”, Journal of Defence Studies, vol. 7, No. 4, October-December (2013), 27-46.

[15] John Lee and Lavina Lee, ‘Win Without Fighting’: The Chinese Communist Party’s Political and Institutional Warfare Against the West”, Hudson Institute, May, 2022, p. 18, https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.hudson.org/Lee_Win%20Without%20Fighting.pdf

[16] “The three methods of public opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare accelerate the victory of the war”, Xinhuanet, March 8, 2005, http://news.sina.com.cn/o/2005-03-08/10245297499s.shtml

[17] Zhang Aiping cited in Paul H. B. Godwin, “Changing Concepts of Doctrine, Strategy and Operations in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army 1978-1987,” The China Quarterly 112 (December 1987): 576.

[18] “The three methods of public opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare accelerate the victory of the war”.

[19] Science of Military Strategy, (Beijing: National Defence University Press), 2020, p. 240, Elsa Kania, “The PLA’s Strategic Thinking of the Three Warfares”, Center for International Maritime Security, August 25, 2016, https://cimsec.org/plas-latest-strategic-thinking-three-warfares/

[20] Kania, “The PLA’s Strategic Thinking of the Three Warfares”.

[21] Kuok, Kuok, “China’s Legal Diplomacy”, p. 160.

[22] Kania, “The PLA’s Strategic Thinking of the Three Warfares”.

[23] Elsa Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares”, China Brief, Volume 16, Issue:13, The Jamestown Foundation, 22 August, 2022, https://jamestown.org/program/the-plas-latest-strategic-thinking-on-the-three-warfares/

[24] “The three methods of public opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare accelerate the victory of the war”.

[25] “The three methods of public opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare accelerate the victory of the war”.

[26] “The three methods of public opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare accelerate the victory of the war”.

[27] “The three methods of public opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare accelerate the victory of the war”.

[28] “The three methods of public opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare accelerate the victory of the war”.

[29] For China’s objection over the shift J&K’s statehood to Union Territory Status (UT), see “India’s decision to make Ladakh UT unacceptable, says China”, Hindustan Times, 7 August, 2019. For Shah’s statement in parliament see “PoK, Aksai Chin part of Kashmir, says Amit Shah in Lok Sabha”, The Hindu, 6 August, 2019, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/pok-aksai-chin-part-of-kashmir-says-amit-shah-in-lok-sabha/article61587371.ece

[30] Jon R. Lindsay, Information Technology & Military Power, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2020), p. 240.

[31] Antara Ghosal Singh, “Analysing the current Chinese discourse on India”, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi, 10 January, 2023, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/analysing-the-current-chinese-discourse-on-india/

[32] There is no publicly available evidence of Indian intelligence intercepting communications between the Xi-led leadership and the PLA’s Western Military Command (WTC).

[33] “Modi accepts Xi’s invitation for third informal summit in China”, India Today, October 12, 2019, https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/modi-accepts-xi-jinping-invitation-third-informal-summit-china-1608717-2019-10-12

[34] See for instance specifically the American expert on South Asia Ashley J. Tellis’ comments on Amit Shah’s statement and the Administrative changes brought about in J&K were responsible for Chinese military action in Eastern Ladakh in discussion with Srinath Raghavan, “Assessing the Sino-Indian Border Confrontation”, Interpreting India, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 17, 2020, https://interpreting-india.simplecast.com/episodes/assessing-the-sino-indian-border-confrontation

[35] Shivshankar Menon, “Are India-China relations crisis-prone?”, Seminar, No. 737, 2021, https://india-seminar.com/2021/737/737_shivshankar_menon.htm

[36] Menon, “Are India-China relations crisis-prone?”.

[37] “China never provoked any war, never occupied an inch of other country, says Bejing”, ThePrint, 1 September, 2020, https://theprint.in/diplomacy/china-never-provoked-any-war-never-occupied-an-inch-of-other-country-says-beijing/493510/

[38] Cited in “China never provoked any war, never occupied an inch of other country, says Bejing”, ThePrint, 1 September, 2020, https://theprint.in/diplomacy/china-never-provoked-any-war-never-occupied-an-inch-of-other-country-says-beijing/493510/

[39] Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares”.

[40] Cited in Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares”. Surprise is integral in war. In ancient China one of the key stratagems followed was “Make a sound in the East, then strike in the West”, which can be found in Peter Taylor, The Thirty-six Strategems: A Modern Interpretation of A Strategy, (Oxford: Infinite Ideas Limited, 2013), 31-32.

[41] See for instance an expert on the Sino-Indian boundary dispute Srinath Raghavan, “Assessing the Sino-Indian Border Confrontation”, Interpreting India, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 17 June, 2020, https://interpreting-india.simplecast.com/episodes/assessing-the-sino-indian-border-confrontation

[42] A Chinese offensive on a massive scale is still possible. India’s leadership misjudged Chinese motivations that led to the 1962 war as is clearly explicated in Srinath Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India, (New Delhi: Orient Blackswan Pvt. Ltd., 2009).

[43]Anne Marie Brady, China as a Polar Great Power, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 3.

[44] Science of Military Strategy, (Beijing: National Defence University Press, 2020), 142-162.

[45] “China’s Arctic Policy”, State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, Xinhua News Agency, January 26, 2018, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2018-01/26/content_5260891.htm

[46] Rush Doshi, Alexis Dale-Huang, and Gaoqi Zhang, “Northern Expedition: China’s Arctic Activities and Ambitions”, Brookings Institution, Washington D.C., April, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/FP_20210412_china_arctic.pdf

[47] “China supportive to China’s bid for permanent observer to Arctic Council”, ChinaDaily, January 22, 2013, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2013-01/22/content_16151497.htm

[48] Doshi et al., “Northern Expedition: China’s Arctic Activities and Ambitions”.

[49] “China’s Arctic Policy”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, Beijing January 26, 2018, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/wjzcs/201801/t20180126_679659.html

[50] “China’s Arctic Policy”. See also a critique of those who seek to conflate Beijing’s territorial claims in the South China Sea with its approach to the Arctic, Marc Lanteigne, “The Arctic is not the South China Sea”, South China Morning Post, May 25, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/3134261/arctic-not-south-china-sea

[51] Elizabeth Buchanan, “China’s Hybrid Arctic Strategy”, per Concordiam, September 8, 2021, https://perconcordiam.com/chinas-hybrid-arctic-strategy/

[52] Doshi et al., “Northern Expedition: China’s Arctic Activities and Ambitions”.

[53] See Elsa Kania, “Thinking of the Three Warfares”, Center for International Maritime Security, August 25, 2016, https://cimsec.org/plas-latest-strategic-thinking-three-warfares/

[54] Kania, “Thinking of the Three Warfares”.

[55] Kania, “Thinking of the Three Warfares”.

[56] In the Matter of the South China Sea Arbitration before An Arbitral Tribunal Constituted Under Annex VII to the 1982 United Nations Convention On the Law of the Sea between The Republic of the Philippines Award, The Hague, 12 July, 2016, p. 472, https://pcacases.com/web/sendAttach/2086

[57] Euan Graham, “The Hague Tribunal’s South China Sea Ruling: Empty Provocation or Slow-Burning Influence?”, Council of Councils, Washington D.C., August 18, 2016, https://www.cfr.org/councilofcouncils/global-memos/hague-tribunals-south-china-sea-ruling-empty-provocation-or-slow-burning-influence

[58] Kania, “Thinking of the Three Warfares”. The South Sea Arbitration (The Republic of Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China, Permanent Court of Arbitration, January 22, 2013, https://pca-cpa.org/en/cases/7/

[59] Elizabeth Buchanan and Bec Strating, “Why the Arctic is Not the ‘Next’ South China Sea”, War on the Rocks, November 20, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/11/why-the-arctic-is-not-the-next-south-china-sea/

[60] Buchanan and Strating, “Why the Arctic is Not the ‘Next’ South China Sea”.

[61] Buchanan, “China’s Hybrid Arctic Strategy”.

[62] Matthew P. Funaiole et al., “Frozen Frontiers: China’s Great Power Ambitions in the Polar Regions”, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Washington D.C., April 18, 2023, https://features.csis.org/hiddenreach/china-polar-research-facility/#:~:text=China%20has%20two%20permanent%20research,marine%20ecology%20to%20atmospheric%20physics

[63] Swee Lean Collin Koh, “China’s strategic interest in the Arctic goes beyond economics”, DefenseNews, May 12, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/opinion/commentary/2020/05/11/chinas-strategic-interest-in-the-arctic-goes-beyond-economics/

[64] Funaiole et al., “Frozen Frontiers: China’s Great Power Ambitions in the Polar Regions”.

[65] Funaiole et al., “Frozen Frontiers: China’s Great Power Ambitions in the Polar Regions”.

[66] Funaiole et al., “Frozen Frontiers: China’s Great Power Ambitions in the Polar Regions”.

[67] Stephanie Pezard, “The New Geopolitics of the Arctic: Russia’s and China’s Evolving and Role”, Testimony presented before the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development of the Canadian House of Commons, Ottawa, p. 6, https://www.rand.org/pubs/testimonies/CT500.html

[68] Paul D. Shinkman, “China Signals Recent Patrols Near Alaska Are Only the Beginning”, U.S.News and World Report, August 8, 2023, https://www.usnews.com/news/world-report/articles/2023-08-08/china-signals-recent-patrols-near-alaska-are-only-the-beginning?rec-type=blueshift

[69] Michael R. Gordon and Nancy A. Youssef, “Russia and China Sent Large Naval Patrol Near Alaska”, The Wall Street Journal, August 6, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/russia-and-china-sent-large-naval-patrol-near-alaska-127de28b

[70] Cited in “China Signals Recent Patrols Near Alaska Are Only the Beginning”.

[71] Anne-Marie Brady, China As A Polar Great Power, (New Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

[72] Yun Sun, “The Northern Sea Route: The Myth of Sino-Russian Cooperation”, Stimson Center, Washington D.C., December 5, 2018, http://stimson.org/wp-content/files/file-attachments/Stimson%20-%20The%20Northern%20Sea%20Route%20-%20The%20Myth%20of%20Sino-Russian%20Cooperation.pdf

[73] Funaiole et al., “Frozen Frontiers: China’s Great Power Ambitions in the Polar Regions”.

[74] United States Army: Regaining Arctic Dominance, Chief of Staff Paper #3, Headquarters, Department of the Army, January 19, 2021, p. 16

[75] “Russia is looking at Asia and for India it could mean…”: MEA during FTA talks”, Mint, April 17, 2023, https://www.livemint.com/news/world/russia-is-looking-at-asia-and-for-india-it-could-mean-mea-jaishankar-during-fta-talks-11681727211086.html

[76] Heather A. Conley et al., “America’s Arctic Moment: Great Power Competition in the Arctic to 2050”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington D.C. March 2020, 10, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/Conley_ArcticMoment_layout_WEB%20FINAL.pdf

[77] Shaheer Ahmad and Mohammad Ali Zafar, Russia’s Reimagined Arctic in the Age of Geopolitical Competition”, Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, March 9, 2022, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/2959221/russias-reimagined-arctic-in-the-age-of-geopolitical-competition/#sdendnote23sym

[78] See this interesting analysis by Michael Handel, “Corbett, Clausewitz and Sun Tzu”, Naval War College Review, Vol. 53, No. 4, Autumn (2000), 106-124.

[79] Nadezhda Filimonova and Svetlana Krivokhizh, “China’s Stakes in the Russian Arctic”, thediplomat, January 18, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/01/chinas-stakes-in-the-russian-arctic/

[80] Funaiole et al., “Frozen Frontiers: China’s Great Power Ambitions in the Polar Regions”.

[81]Vitaly Yermakov and Ana Yermakov, “Northern Sea Route as Energy Bridge”, in Arctic Fever: Political, Economic and Environmental Aspects”, ed. Anastasia Lichacheva, (Singapore: Palgrave MacMillan, 2022), pp. 473-496.

[82] Anne-Marie Brady, “China’s undeclared foreign policy at the poles”, theinterpreter, The Lowy Institute, May 30, 2017, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/china-s-undeclared-foreign-policy-poles

[83] Doshi et al., “Northern Expedition: China’s Arctic Activities and Ambitions”.

[84] This aligns well with Chinese strategic thought epitomized by Sun Tzu, but also Western thought as shown in Michael Handel, “Corbett, Clausewitz and Sun Tzu”, p. 111

[85] “Yin Zhuo: US maritime hegemony threatens China’s security”, China Net and Netease, March 8, 2010, http://www.china.com.cn/fangtan/zhuanti/2010lianghui/2010-03/08/content_19556085.htm

[86] Science of Military Strategy, 142-162.

[87] “Yin Zhuo: US maritime hegemony threatens China’s security”.

[88] Barry Gardiner, “As the ice melts, a perilous Russian threat is emerging in the Arctic”, The Guardian, June 13, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jun/13/arctic-russia-nato-putin-climate

[89] Jinlei Chen, et al., “Projected Changes in sea ice and the navigability of the Arctic passages under global warming of 2 ℃ and 3 ℃”, Anthropocene, Volume 40, December 2022.

[90] “Shipping traffic at the NSR in 2022”, Northern Sea Route Information Office, Nord University, June 9, 2022, https://arctic-lio.com/nsr-2022-short-report/

[91] Funaiole et al., “Frozen Frontiers: China’s Great Power Ambitions in the Polar Regions”.

[92]Funaiole et al., “Frozen Frontiers: China’s Great Power Ambitions in the Polar Regions”.

[93] Thomas Nilsen, “New mega-port in Arkhangelsk with Chinese investments”, thebarentobserver, October 21, 2016, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/industry-and-energy/2016/10/new-mega-port-arkhangelsk-chinese-investments

[94] Funaiole et al., “Frozen Frontiers: China’s Great Power Ambitions in the Polar Regions”.

[95] Andrea Kendall-Taylor and David O. Shullman, “China and Russia’s Dangerous Convergence: How to Counter an Emerging Partnership”, Foreign Affairs, May 3, 2021.

[96] Regaining Arctic Dominance: The U.S. Army in the Arctic, Headquarters, Department of the Army, January 19, 2021, p. 26.

[97] Regaining Arctic Dominance: The U.S. Army in the Arctic.

[98] Regaining Arctic Dominance: The U.S. Army in the Arctic.

[99] Regaining Arctic Dominance: The U.S. Army in the Arctic.

[100] Joe Varner, “Canada’s Arctic Problem”, Modern War Institute at Westpoint, February 2, 2021, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/canadas-arctic-problem/

[101] Carla Babb, “Army Resurrects WWII – Era Airborne Division in Alaska”, voanews, June 6, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/army-resurrects-wwii-era-airborne-division-in-alaska-/6606224.html

[102] Lily Kuo, “Why China just built this lantern- shaped research base in Antarctica”, Quartz, February 10, 2014, https://qz.com/175325/why-china-just-built-this-lantern-shaped-research-base-in-antarctica

[103] Brady, China As A Polar Great Power, p. 24.

[104] Brady, China As A Polar Great Power, p. 24.

[105] “Parties”, Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty, https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Parties?lang=e.

[106] “The Antarctic Treaty”, p. 25, https://documents.ats.aq/keydocs/vol_1/vol1_2_AT_Antarctic_Treaty_e.pdf

[107] “Parties”, Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty.

[108] “Yin Zhuo: “US maritime hegemony threatens China’s security”.

[109] “Yin Zhuo: “US maritime hegemony threatens China’s security”.

[110] Cited in Nicola Davidson, “China eyes Antarctica’s resource bounty”, China Dialogue, November 19, 2013, https://chinadialogue.net/en/business/6517-china-eyes-antarctica-s-resource-bounty/

[111] Brady, China As A Polar Great Power, p. 11.

[112] Kania, “Thinking of the Three Warfares”.

[113] Brady, China As A Polar Great Power, p. 26.

[114] Cited in Nengye Liu, “What Does China’s Fifth Research Station Mean for Antarctic Governance?”, TheDiplomat, June 28, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/06/what-does-chinas-fifth-research-station-mean-for-antarctic-governance/

[115] Cited Liu, “What Does China’s Fifth Research Station Mean for Antarctic Governance?”.

[116] “Parties”, The Antarctica Treaty, https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Parties?lang=e

[117] Alice Slevison, “Considering China’s strategic interests in Antarctica”, The Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, February 5, 2016, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/considering-chinas-strategic-interests-in-antarctica/

[118] Anthony Bergin and Marcus Haward, “Frozen Assets: Securing Australia’s Antarctic Future”, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra, 2007, p. 6.

[119] Bergin and Haward, “Frozen Assets: Securing Australia’s Antarctic Future”.

[120] Slevison, “Considering China’s strategic interests in Antarctica”.

[121] Liu, “What Does China’s Fifth Research Station Mean for Antarctic Governance?”.

[122] Henry Belot, “Australia would be ‘naïve’ to think China’s new Antarctic station not for surveillance, analyst says”, The Guardian, April 19, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/apr/19/australia-would-be-naive-to-think-chinas-new-antarctic-station-not-for-surveillance-analyst-says

[123] Belot, “Australia would be ‘naïve’ to think China’s new Antarctic station not for surveillance, analyst says”.

[124] Belot, “Australia would be ‘naïve’ to think China’s new Antarctic station not for surveillance, analyst says”.

[125] Kuo, “Why China just built this lantern- shaped research base in Antarctica”.

[126] Ian Bremmer, “China’s Ambitious Plans in Antarctica have Raised New Suspicions”, Time, April 28, 2023, https://time.com/6274924/china-antarctica-south-pole-us-tension/

[127] Belot, “Australia would be ‘naïve’ to think China’s new Antarctic station not for surveillance, analyst says”.

[128] Anne-Marie Brady, China as a Polar Great Power, (Washington D.C: Cambridge University Press, 2017), p. 164.

[129] Anne-Marie Brady, “China’s Rise in Antarctic Rise?” Asian Survey, Vol. 50, No. 4, July-August, 2010, p.776

[130] Funaiole et al., “Frozen Frontiers: China’s Great Power Ambitions in the Polar Regions”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington D.C., April 19, 2023,https://features.csis.org/hiddenreach/china-polar-research-facility/

[131] “Peaceful use and inspections”, Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty, https://www.ats.aq/e/peaceful.html

[132] “Peaceful use and Inspections”.

[133] See the entire International Court of Justice assessment and verdict on China’s maritime territorial claims against the Philippines. In the Matter of the South China Sea Arbitration before An Arbitral Tribunal Constituted Under Annex VII to the 1982 United Nations Convention On the Law of the Sea between The Republic of the Philippines Award, pp. 471-476.

[134] Kuo, “Why China just built this lantern- shaped research base in Antarctica”.

[135] Robert Delaney, “Xi Jinping has yet to decide whether to order Taiwan unification by 2027: top US military adviser”, South China Morning Post, July 1, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/3226202/xi-jinping-has-yet-decide-whether-order-taiwan-unification-2027-top-us-military-adviser

[136] Michael Howard and Peter Paret, trans and edited, On War, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), pp. 94-95.

[137] See all the Quad joint statements over the last three years. “Joint Statement of Quad Leaders”, The White House, Washington D.C., September 24, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/24/joint-statement-from-quad-leaders/, “Quad Joint Leaders’ Statement”, The White House, Washington D.C., May 24, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/05/24/quad-joint-leaders-statement/, “Quad Leaders Joint Statement”, Prime Minister of Australia, Canberra, May 20. 2023, https://www.pm.gov.au/media/quad-leaders-joint-statement

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV