-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

India’s inability to develop interdependencies with neighbouring countries, both economically and strategically, has left a void that China has dutifully filled. There still remains a window for India to correct its past mistakes and develop a concerted strategy to regain influence in the region.

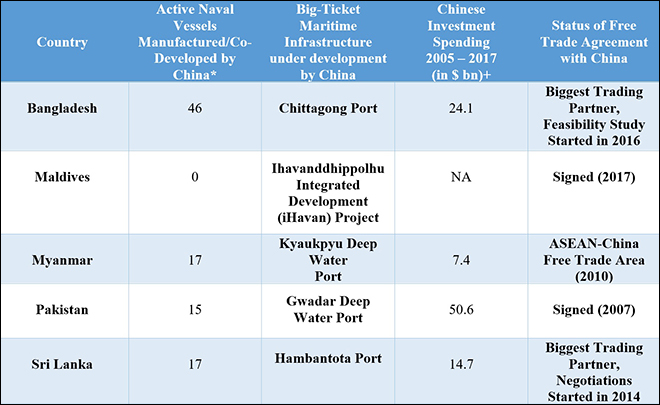

Over thirteen years after defense contractor Booz Allen Hamilton produced a report for US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld warning of China’s plans to increase its maritime footprint in littoral South Asia, the building blocks for a Chinese support network of logistical stations therein is now being put into place. Over the years, China has managed to string together a patronage network of multiple South Asian coastal nations through massive investment spending, focused port development projects, and collaborative naval equipment transfers (refer Table 1 below). The formulation of this “string of pearls” strategy, furthering China’s larger military and commercial ambitions under the guise of economic development, has managed to bait nations out of India’s strategic orbit.

The recent ideological shift undertaken by the Abdulla Yameen administration in the Maldives is an instance of this metamorphosis. The transformation of the island state from a pro-India bastion to a Chinese client state actualises the militaristic dimension of Beijing’s prophetic strategy, and marks an inflection point in Sino-Indian maritime dynamics. Since the Maldives represents a buffer zone surrounding India’s maritime strategic space, China’s steady encroachment there is a serious cause for concern. To address this, bold policy decisions are required from New Delhi. And while there are multiple strategic options for Indian policymakers to counter Chinese containment, India’s principled position of “strategic autonomy” must also be reformed.

China has employed a combination of hard military tactics, political patronage, and an ever-widening list of economic dependents to gain a foothold in South Asia, progressing relatively unchecked in this quest. India, the traditional South Asian naval power, has been unable to match China on both strategic and economic support to countries in the region. As Table 1 below demonstrates, South Asian navies have procured Chinese naval assets in large numbers, at times engaging in joint development of combat ships and submarines. Secondly, Chinese investment in big-ticket maritime infrastructure, especially deep-water ports, underscores the commercial maritime dependency of these countries on China.

Table 1: Economic and strategic relationships of selected littoral South Asian countries with China

*Figures according to IISS Military Balance 2018 (Chapter 6: Asia)

+Figures from American Enterprise Institute via CNN

The dual use of these ports for surveillance missions cannot be entirely discounted given China’s primary aim to secure its sea lines of communication (SLOCs) in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). The Indian Ocean and its surrounding waters are home to China’s principal shipping lanes, and there is need to guard its economic and energy security against an adversarial power seeking to infringe on Chinese access to these waters. China has, therefore, embarked on an agenda to actualise a commercial support base in the IOR, which could later be leveraged militarily.

Using the Maritime Silk Road as a pretext for this strategy, China has established interdependencies between itself and various South Asian states. This includes Sri Lanka, which, saddled with enormous Chinese debt, leased out its Hambantota Port project to Chinese state-controlled entities, and Pakistan, for whom China is developing the Gwadar port, as part of the China-Pakistan-Economic-Corridor (CPEC). Many of these countries have also either already established free-trade agreements with China or are currently negotiating towards one.

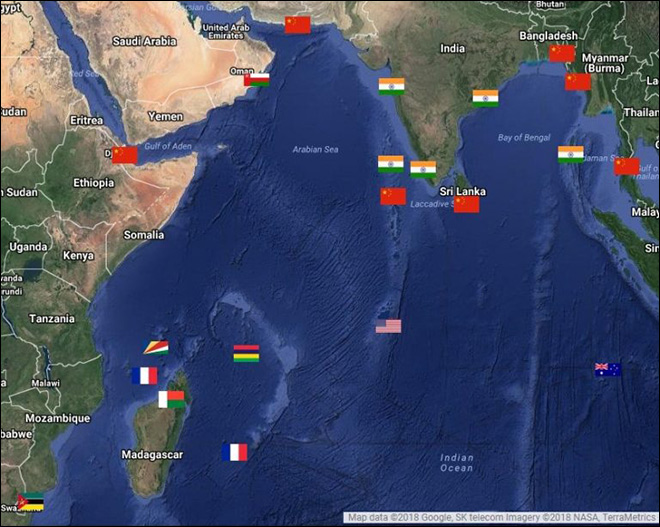

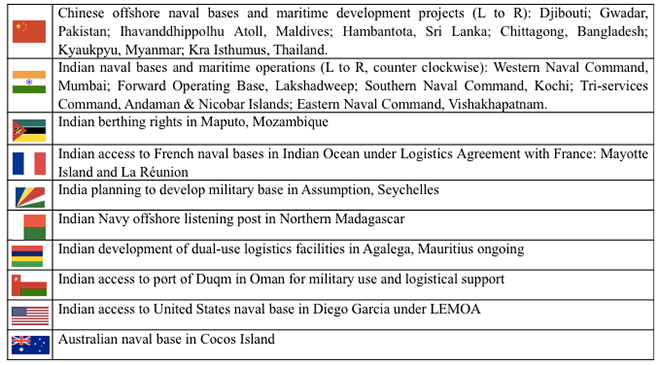

There were multiple signs along the way to suggest China’s gradual encirclement of India, as shown in Figure 1 below, but between strategic complacency and Sinophobia, the possibility of China gaining an upper hand over India in the Indian Ocean was largely dismissed in New Delhi.

A strategically-isolated India will not be able to balance the financial and military might of China, and clinging onto a Cold War era non-alignment mentality might seem dynamic in the short-term, but in the long term, New Delhi’s ability to maneuver shipping lanes in its own backyard could be threatened by the Chinese.

The latest pearl in China’s ascendancy string is the Maldives, an archipelago lying at the edge of India’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The Maldives case marks the evolution of a commercial partner into a geopolitical ally for China: Beijing implicitly supported President Yameen in his purge of dissenting elements in the island nation and warned against Indian intervention. The intensity of India-China maritime competition came to the fore when, after a state of emergency was declared in the Maldives, India held a massive naval exercise in the Eastern Indian Ocean, initiating its standard operating procedure (SOP) for the island. Reports later pointed to the presence of a Chinese amphibious task-force conducting drills in the area around the same time.

This demonstrates Chinese naval power in the IOR, with Beijing further promising to develop a new economic zone in the island’s northernmost atoll — Ihavanddhippolhu — known as the iHavan project. With the Maldives long considered a natural extension of India’s security expanse, a Chinese support base in the archipelago is an Indian strategist’s worst nightmare because such a base would allow China to monitor the strategic corridor that links India’s western and eastern coastlines. This latest infringement of India’s maritime space warrants an unequivocal strategic rejoinder from New Delhi.

Figure 1: China and India’s maritime footprint in the Indian Ocean

The concept of strategic buffer zones in the naval domain is enshrined in great power politics. In the current era, naval powers like the United States and China have both established cushions to avoid anti-access and area denial tactics from adversaries. The Eastern Pacific Ocean acts as a strategic barrier against any adversarial action taken on US mainland while the South China Sea does the same for China. India should develop a similar outlook to guard against Chinese encirclement of its strategic space. Disregarding its longstanding policy of “strategic autonomy,” India must recognise the benefits of partnering with non-residential maritime powers in the Indian Ocean. A strategically-isolated India will not be able to balance the financial and military might of China, and clinging onto a Cold War era non-alignment mentality might seem dynamic in the short-term, but in the long term, New Delhi’s ability to maneuver shipping lanes in its own backyard could be threatened by Chinese belligerence. India needs to shed its traditional strategic reticence and ensure the safety of its own SLOCs.

Thus, the way forward for New Delhi would be to operationalise logistical agreements with France and the United States, in order to upgrade naval relations to gain berthing rights to Diego Garcia, Mayotte Island, and < lang="fr" xml:lang="fr">La Réunion, and allow its own bases to be used for logistical support by the French and American navies. Additionally, India can offer similar reciprocal berthing rights to Australia and gain access to its naval base in Cocos Islands, as shown in Figure 1. By cultivating naval cooperation with these states, New Delhi will benefit from tacit naval alliances in the future. Furthermore, it will benefit from developing, at the very least, logistical support stations on Assumption Island in the Seychelles and Agalega in Mauritius, building upon its already existing listening post in northern Madagascar. Correspondingly, New Delhi can step up the use of existing berthing rights with Duqm Port in Oman and Maputo in Mozambique.

The options for India are simple — either it acquiesces to a Chinese hierarchy in the region by letting Beijing encroach upon its sphere of influence, or it takes a stand to preserve its strategic space and counters China’s containment strategy by expanding its nautical reach.

Further, connecting these offshore stations with its on-shore naval commands and island-based operating bases will allow the Indian Navy a larger operational expanse beyond its immediate buffer zones. These logistical bases can also enhance India’s capability to establish sea-denial in the Indian Ocean, demonstrating the breadth of Indian naval power. These moves should be accompanied with counter-theatre presence in the Western Pacific, and diplomatic outreach to South Asian nations that are being courted by China. A combination of these strategies might not guarantee against Chinese influence in littoral South Asian nations, but will at least ensure that India is not tied down by Chinese client states in its own sphere of influence.

India’s inability to develop interdependencies with neighbouring countries, both economically and strategically, has left a void that China has dutifully fulfilled. There still remains a window for India to correct its past mistakes and develop a concerted strategy to regain influence in the region. The lack of an Indian grand strategy in its neighbourhood cannot be emphasised enough, and it is alarming that consecutive Indian establishments have been unable to arrest this declining influence, while China’s economically-hostile developmental assistance accompanied with naval technology transfers intertwine the region in a web of institutional dependency. The options for India are simple — either it acquiesces to a Chinese hierarchy in the region by letting Beijing encroach upon its sphere of influence, or it takes a stand to preserve its strategic space and counters China’s containment strategy by expanding its nautical reach.

This commentary originally appeared in South Asian Voices.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Rob McInerney Chief Executive Officer International Road Assessment Programme Australia

Read More +