-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Sushant Sareen, “China and Pakistan’s ‘Iron Brotherhood’: The Economic Dimensions and their Implications on US Hegemony”, ORF Occasional Paper No. 183, February 2019, Observer Research Foundation.

In one of his first tweets on the first day of 2018, US President Donald Trump accused Pakistan of “lies and deceit”, and lamented having “foolishly given Pakistan more than 33 billion dollars in aid over the last 15 years”. He ended his tweet with the words, “No more!”.[i] The tweet—and the subsequent suspension of US$255 in military aid[ii]—was greeted in Pakistan with a combination of outrage and bravado.[iii] Pakistan’s foreign minister, Khawaja Asif, declared that Pakistan can survive without US aid as it had in the past. He also rejected any notion of Pakistan being diplomatically isolated and said, “China, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Russia, and Iran expressed complete solidarity with us after August 21 speech of US President Trump (outlining US’ South Asia Policy).”[iv] The Pakistan military spokesperson threatened that the aid suspension will impact bilateral security cooperation, but added that Pakistan did not fight for money but for peace.[v]

Pakistan appeared unconcerned. After all, China had also just then reiterated its commitment to “further deepen cooperation with Pakistan.”[vi] The then adviser to the prime minister on finance (and later finance minister) Miftah Ismail, brushed aside the impact of US aid suspension and said that Pakistan did not seek US financial assistance and Pakistan’s “economic health was safe and bright on account of CPEC related activities.”[vii] According to Pakistan’s calculations, the aid it was receiving from the US had historically been only less than one percent of the country’s budget and therefore could be easily made up for by other sources.[viii]

In the US, too, various analysts and officials expressed scepticism about the efficacy of using the threat of denying economic and military aid as a leverage to force compellence on Pakistan. They argued that by suspending or stopping all aid to Pakistan, the US would lose whatever little influence it still exercised on Pakistan; that aid, in fact, was one of the few remaining tools for the US in its relations with Pakistan. The more the US tightened the screws on Pakistan, the faster it would push Pakistan into China’s sphere of influence.[ix] These same analysts theorise that Pakistan’s inexorable slide into China’s clutch can at least be stalled, if not entirely stopped, by keeping the aid tap open.[x]

Pakistan, for its part, even as it continues to defy the US and dismiss threats of an aid cut, continues to encourage America to use aid as a tool to retain its influence.[xi] The last thing Pakistan wants is open and unbridled US hostility, which will inevitably impact on Pakistan’s relations with other Western countries, multilateral financial institutions, international financial markets, and even Arab states that have bankrolled Pakistan.[xii]

Pakistan would not want a complete break with the US and stake all with China for another important reason. Ideally, Pakistan is keeping the US as an option in case ties start to sour with China. While China has not been overbearing as yet, there have been occasions when it has proved that it can be so.[xiii] As China gets more deeply embedded in the Pakistani system, it could become more demanding, especially on issues where the positions of the two countries may diverge. For example, Pakistan has yet to take a firm position about China’s treatment of its Muslim minorities. While there are media reports of Pakistan raising the issue with China, both sides have denied it.[xiv]

The infrastructure project, China-Pakistan Economic Corridor or CPEC, is another issue that could cause a cleavage between China and Pakistan. While the project has been touted as a game changer for Pakistan, there are worries that CPEC will only serve to further expand Chinese footprint in Pakistan..[xv] In private gatherings, senior Pakistani military officials have been heard saying that they “took the Americans for a ride” for 70 years and now “its China’s turn.”[xvi] Indeed, even as the Pakistani civilian government is publicly calling for a review of CPEC projects, the Pakistan Army chief has declared commitment to the Corridor.

What is certain is that today, China occupies the privileged position in Pakistan that a few decades back was reserved for the US. Over the past many years, Pakistan has looked for viable alternative options to the US – i.e. China, for the longest time, and increasingly, too, Russia. The clout that the US wielded on Pakistan by virtue of its long history of providing economic and military assistance, has considerably weakened. For Pakistan, the price it will pay for continued US support is not worth the compromise it must make in its strategic calculus.

Even in the realm of public opinion, China is seen as a dependable ally and true friend while the US is fickle and overbearing. Among Pakistan’s policymaking circles, China’s importance cannot be overstated, not only in terms of the defence and security relationship but also increasingly in diplomatic and political support. While the US has been distancing itself from Pakistan and not giving it the sort of support it did in the previous century, China has bailed out Pakistan, both economically and diplomatically.[xvii]

Consequently, while US demands, hectoring and inimical moves are received in Pakistan with equanimity, there is enormous trepidation when China puts the spotlight on Pakistan in a negative way. China’s stance becomes an argument for reform and correction for Pakistan,[xviii] while US demands tend to provoke defiance.[xix]

The roots of China-Pakistan relations are old, born out of their shared animosity towards India. As China’s relations with India started going south, its relations with Pakistan blossomed; in 2002, a top Chinese general termed Pakistan as “China’s Israel”.[xx] The 1962 Sino-Indo war cemented the Sino-Pak relationship. For the first few decades, at least until the turn of the 21st century, Pakistan was able to maintain a balance in its relations with both the US and China. The fact that US-China engagement picked up momentum as China opened up its economy in the 1970s, benefited Pakistan: as China gained in strength, its utility as a counter-balance to India increased. Equally important was the fact that Pakistan did not face any pressure from its primary patron, the US, to restrict its relations with China. Pakistan got the best of both worlds, so to speak – the US supplied it with modern weapons and economic assistance, while China assisted Pakistan in building its defence capabilities and its nuclear programme.[xxi]

What drew Pakistan closer to China was the unreliability of US assistance. Although, until the first decade of the 21st century, China was not seen as a replacement for the US. The rise of China and its emergence as a major global player, coupled with the perception of the decline of the US, hastened the process of Pakistan looking upon China as a real and viable alternative to the US.

As can be seen from Table 1 and Graph 1, the first weapons deal between China and Pakistan took place in 1964 after the border agreement between China and Pakistan following the 1962 Sino-Indo war. In 1965, the US imposed an arms embargo on Pakistan. At that point, China stepped in to supply weapons and military equipment to Pakistan. The US-Pakistan defence relationship remained lukewarm until the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, afterwhich Pakistan once again became a “frontline state” for the US, and the beneficiary of its weapons transfers. This ended in the 1990s after the Pressler Amendment was invoked.[xxii] China once again stepped in. Until 9/11 and the US-led ‘War on Terror’ in its aftermath, China dominated the weapons trade with Pakistan. After 9/11, the US restarted its military assistance to Pakistan, but except for the period from 2003-04 to 2010, China continued to be the bigger partner. Since 2010-11, the US weapons trade with Pakistan has steadily fallen while China’s remains robust. Over the last 70 years, according to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), in aggregate terms, China’s arms trade with Pakistan is close to double that of the US. The data imply that while the US has always maintained a transactional relationship with Pakistan to serve its own strategic interests, in the case of China it was the mutuality of strategic interests – i.e., the India factor – that formed the basis of the similarly transactional relationship. With the US moving closer to India, it no longer serves Pakistan’s interests to hedge the perceived threat from India; to begin with, Pakistan’s interest is centred around finding a partner, or more appropriately a patron. China, for the time being at least, fits the bill.

Graph 1

Table 1.

| Arms Trade with Pakistan | |||

| Year | China | USA | |

| 1950 | 36 | ||

| 1951 | |||

| 1952 | 0 | ||

| 1953 | |||

| 1954 | 53 | ||

| 1955 | 135 | ||

| 1956 | 155 | ||

| 1957 | 242 | ||

| 1958 | 168 | ||

| 1959 | 323 | ||

| 1960 | 42 | ||

| 1961 | 69 | ||

| 1962 | 88 | ||

| 1963 | 198 | ||

| 1964 | 2 | 81 | |

| 1965 | 165 | 16 | |

| 1966 | 448 | 6 | |

| 1967 | 117 | ||

| 1968 | 168 | 11 | |

| 1969 | 158 | ||

| 1970 | 183 | ||

| 1971 | 346 | ||

| 1972 | 489 | 0 | |

| 1973 | 121 | 31 | |

| 1974 | 11 | 95 | |

| 1975 | 76 | 51 | |

| 1976 | 135 | 24 | |

| 1977 | 25 | 24 | |

| 1978 | 297 | 200 | |

| 1979 | 217 | 46 | |

| 1980 | 245 | 194 | |

| 1981 | 207 | 36 | |

| 1982 | 77 | 93 | |

| 1983 | 418 | 254 | |

| 1984 | 289 | 479 | |

| 1985 | 105 | 549 | |

| 1986 | 68 | 134 | |

| 1987 | 422 | 97 | |

| 1988 | 123 | 79 | |

| 1989 | 324 | 608 | |

| 1990 | 325 | 55 | |

| 1991 | 283 | 28 | |

| 1992 | 210 | 25 | |

| 1993 | 697 | 26 | |

| 1994 | 346 | 25 | |

| 1995 | 234 | 25 | |

| 1996 | 115 | 188 | |

| 1997 | 93 | 135 | |

| 1998 | 92 | 25 | |

| 1999 | 73 | 8 | |

| 2000 | 69 | 11 | |

| 2001 | 299 | 15 | |

| 2002 | 286 | 44 | |

| 2003 | 267 | 24 | |

| 2004 | 77 | 74 | |

| 2005 | 78 | 171 | |

| 2006 | 98 | 109 | |

| 2007 | 144 | 395 | |

| 2008 | 250 | 303 | |

| 2009 | 758 | 146 | |

| 2010 | 747 | 1027 | |

| 2011 | 578 | 269 | |

| 2012 | 583 | 276 | |

| 2013 | 719 | 151 | |

| 2014 | 413 | 198 | |

| 2015 | 597 | 73 | |

| 2016 | 673 | 39 | |

| 2017 | 514 | 21 | |

One of the great ironies of Pakistan’s relations with the US and China is that even though the US has coined the aphorism, “there is no such thing as a free lunch”, it has given plenty of free lunches to Pakistan in terms of grants. China, on the other hand, despite being ideologically inclined to doling out free lunches in keeping with its socialistic ambitions, has done little in this regard. Data from Pakistan Economic Surveys since 1980-81 reveal the scale of US assistance in terms of loans and grants. According to data from the Pakistan’s finance ministry (See Table 4), it was not until 1996-97 that the first grant assistance agreement was initialled by China. Since then, except for two years – 2010-11 and 2014-15 – when a respectable amount was given as grant, China has given a pittance in grants to Pakistan – only around US$600 million. Compared to China, in the entire period since 1980-81, America has given Pakistan almost US$ 8 billion in grants.[xxiv]

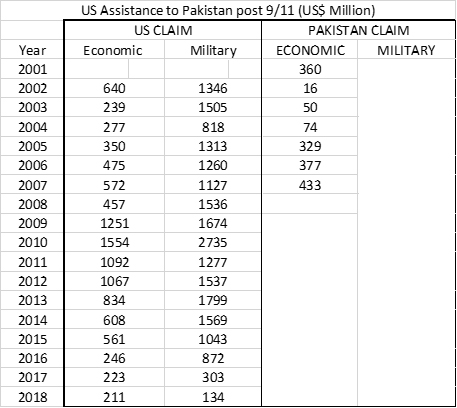

The US grants were, however, aligned with its strategic requirements. During the 1980s the grants flowed as Pakistan became the “frontline state” against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. After 1990-91, the aid tap was virtually turned off for a decade until 9/11, when the US’ War on Terror made Pakistan relevant once again. Another decade later, after the Abottabad operation in which the Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden was slain, US-Pakistan relations went downhill once again. Pakistan’s official budge documents show that after 2012, US grants reduced to a trickle. (See Table 2).

Table 2.

| Estimates of Foreign Assistance | ||

| CHINA | USA | |

| Year | ||

| 2011-12 | 42 | 9 |

| 2012-13 | 58 | 13 |

| 2013-14 | 72 | 26 |

| 2014-15 | 194 | 11 |

| 2015-16 | 144 | 19 |

| 2016-17 | 134 | 7 |

| 2017-18 | 150 | 10 |

| All figures in PKR billion (rounded off to nearest billion) | ||

Graph 2.

There is a huge discrepancy between the aid that the US claims to have given and what Pakistan records as having been received. This is in part because while Pakistan takes into account only the aid that was disbursed through the government of Pakistan, the US includes in its accounting the assistance to the private sector and NGOs.[xxvi] According to Pakistan, in the 17 years since 9/11, the country received on an average only US$250 million annually.[xxvii] Quoting official data, Pakistani newspapers reported that there was a huge gap between commitments and actual disbursements in US-funded projects.[xxviii] The finance adviser, Miftah Ismail, calculated that Pakistan received only around US$27-28 billion since 2001, and not over US$33 billion as claimed by President Trump in that tweet of 1 January 2018. Out of the amount received, over US$14 billion was in the form of reimbursements (Coalition Support Funds) for expenses that Pakistan had made and therefore did not technically qualify as US assistance.[xxix]

Graph 3.

Table 3.

Table 4.

Table 4 shows interesting patterns. In the 1990s, although the US stopped giving grants to Pakistan, it continued to sign loan and credit agreements. Following 9/11, while American aid spiked, there were no loans and credits contracted between the US and Pakistan. China, which has been parsimonious with their grant assistance, was similarly reluctant to give big loans and grants to Pakistan until the start of this century. For almost 20 years from 1980-81 to 2000-01, the loans and credit contracted by Pakistan with China were very modest. Around the time the US started plying economic and military assistance to Pakistan – 2002 onwards – the Chinese loans and credits started to balloon. After the global financial crisis in 2007-08, when China began to emerge as a global financial and economic power to reckon with, the loans and credits contracted by Pakistan rose. And from 2013-14 onwards, with the agreement on the CPEC project, huge amounts of loans were given to Pakistan. Over the entire period from 1980-81, the total quantum of loans and credits contracted by Pakistan with the US and China – US$4.6 billion and over US$21 billion, respectively – lays out the entire story of Pakistan’s growing indebtedness to China. The data collated by independent scholars is, in fact, even more stark as it reveals that the total amount of Pakistan’s loans from China since 1997 are almost US$26 billion since 1997, while the grants are double of what is shown in Pakistan official documents – i.e., over US$1.2 billion (See Table 5).

Table 5.

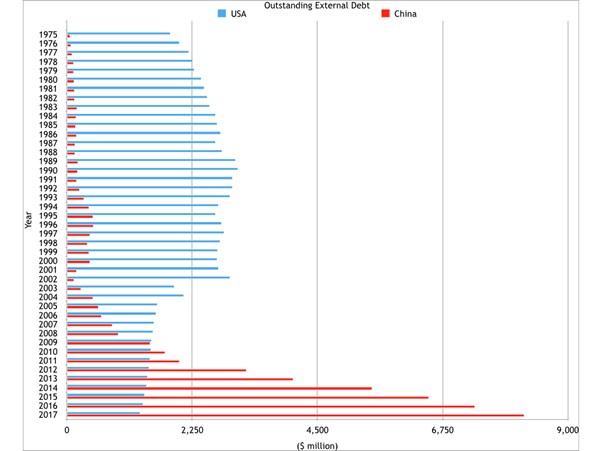

Setting aside such discrepancies in data as reported by Pakistan, and those from the US and China, what is clear is the trajectory of Pakistani indebtedness to China. Data published by the State Bank of Pakistan on country-wise outstanding debt shows how the Chinese debt has risen in this decade even as the US debt has steadily fallen (See Table 6).

Table 6. [xxxiii]

| Outstanding External Debt | |||

| ($ million) | |||

| Year | USA | CHINA | |

| 1975 | 1,856 | 53 | |

| 1976 | 2,015 | 74 | |

| 1977 | 2,187 | 91 | |

| 1978 | 2,261 | 115 | |

| 1979 | 2,290 | 120 | |

| 1980 | 2,416 | 127 | |

| 1981 | 2,470 | 138 | |

| 1982 | 2,521 | 136 | |

| 1983 | 2,563 | 181 | |

| 1984 | 2,667 | 163 | |

| 1985 | 2,699 | 158 | |

| 1986 | 2,763 | 169 | |

| 1987 | 2674 | 147 | |

| 1988 | 2787 | 142 | |

| 1989 | 3028 | 200 | |

| 1990 | 3070 | 192 | |

| 1991 | 2975 | 171 | |

| 1992 | 2970 | 230 | |

| 1993 | 2930 | 305 | |

| 1994 | 2725 | 397 | |

| 1995 | 2675 | 464 | |

| 1996 | 2779 | 477 | |

| 1997 | 2824 | 412 | |

| 1998 | 2752 | 369 | |

| 1999 | 2,705 | 397 | |

| 2000 | 2,702 | 409 | |

| 2001 | 2,722 | 172 | |

| 2002 | 2,927 | 128 | |

| 2003 | 1,929 | 256 | |

| 2004 | 2,104 | 466 | |

| 2005 | 1,627 | 568 | |

| 2006 | 1,603 | 619 | |

| 2007 | 1,567 | 817 | |

| 2008 | 1,542 | 925 | |

| 2009 | 1,524 | 1,491 | |

| 2010 | 1,507 | 1,762 | |

| 2011 | 1490 | 2020 | |

| 2012 | 1472 | 3224 | |

| 2013 | 1451 | 4063 | |

| 2014 | 1427 | 5481 | |

| 2015 | 1399 | 6496 | |

| 2016 | 1368 | 7329 | |

| 2017 | 1313 | 8209 | |

Table 6 shows that in the last 10 years, Pakistan’s outstanding debt to China has risen every year by around a billion dollars. By the end of financial year 2017, while Pakistan owed the US just over US$1.3 billion, the outstanding debt with China had galloped to over US$8 billion. The manner in which China has replaced the US as the principal financier of Pakistan is apparent from the graphical representation in Graph 4.

Graph 4.

In July 2018, the US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned that the US would obstruct any bailout for Pakistan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) if it meant giving money to Pakistan to repay its loans to China.[xxxiv] The warning seemed to validate concerns expressed by Pakistani economists on how the US could use its influence in multilateral financial institutions like IMF and World Bank and prevent them from giving budgetary and Balance of Payments support to Pakistan.[xxxv] Pakistan, however, insisted that the debt repayments to China were a fraction of Pakistan’s debt servicing obligations. The then finance minister, Miftah Ismail, scoffed at talk of Chinese loans breaking Pakistan’s back and claimed that the annual debt repayments and profit expatriation would not cross US$1 billion until 2023.[xxxvi] China, too, weighed in on the debate of “debt-trap diplomacy”, using data from Pakistan’s finance ministry that say the debts contracted under CPEC framework were only 10 percent of Pakistan’s total foreign debt. The bulk of Pakistan foreign debt was held by Western countries (18 percent) and multilateral financial institutions (42 percent). China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi claimed that 47 percent of Pakistan’s foreign debt was held by ADB and IMF.[xxxvii] The issue, however, is not only about the quantum of Pakistan’s loans from China, but also the speed at which they have been rising. Moreover, CPEC is being critiqued for its “shadowy funding mechanism”, the details of which have still not been made public.[xxxviii] Clearly, the data outlined above tells part of the story.

The data released by the Economic Affairs division (EAD) of the Ministry of Finance, Government of Pakistan, is quite stark on the amount of money that has been pumped in by China as loans to Pakistan. Since the year 2006-07, China has committed some US$21.3 billion and disbursed US$9.3 billion to Pakistan. The disbursement amount does not include the US$4.5 billion that Chinese commercial banks have lent Pakistan for Balance of Payments (BOP) support (See Table 7.) Compared to Chinese loans, the EAD data puts US grant commitments during the same period at around US$4 billion and actual disbursements at only US$2.3 billion. Calculations made by a Pakistani investment house reveal that Pakistan will end up paying around US$90 billion over the next 30 years to China against the loan and investment portfolio of around US$50 billion. The average annual repayments will be US$3 billion per year, initially, and between 2020-25 the repayments will range between US$2 billion and $5.3 billion per year.[xxxix]

Table 7.

As far back as March 2017, independent economists in Pakistan had estimated that the CPEC loans would add US$14 billion to the country’s total foreign debt. The total was initially expected to cross US$90 billion by the end of fiscal year 2018-19, but had in fact breached the US$100-billion mark by December 2018 as the Imran Khan government contracted various loans from Saudi Arabia, UAE and China. The same economists also projected that because the CPEC loans and profits were underwritten with sovereign guarantees, the debt servicing payments would rise to over US$8.3 billion by the end of 2018-19. Despite the fact that these projections were dismissed as “alarmist”, they have turned out to be quite accurate. [xli]

After US Secretary of State Pompeo’s July 2018 warning, Pakistan started doing the math on getting bailout packages to repay the instalments of CPEC projects. Initially, there was the typical underestimation of the quantum of money required and how it would be obtained.[xlii] By the end of the year, a news report revealed that the Ministry of Planning and Development, the nodal ministry for CPEC, had calculated that Pakistan would have to pay nearly US$40 billion in debt repayments and dividend over 20 years to China for the latter’s US$26.5-billion investment (See Table 8). This US$40 billion included debt repayments of US$28.5 billion and dividend of US$11.5 billion. Even as the actual Chinese investments of around US$26 billion were only less than half of the massive figure of US$60 billion that Pakistan had initially expected, the average annual repayments would be around US$2 billion. The bigger problem, however, was not the average amount but the fact that the repayments would rise in the next decade before tapering off.[xliii]

Table 8.

|

Projected Outflow of Dividend and Debt on CPEC Projects ($ Million) |

|

| Year | Outflow |

| 2016-17 | 31 |

| 2018-18 | 219 |

| 2018-19 | 42 |

| 2019-20 | 1009 |

| 2020-21 | 1226 |

| 2021-22 | 1883 |

| 2022-23 | 2686 |

| 2023-24 | 2877 |

| 2024-25 | 2925 |

| 2025-26 | 3233 |

| 2026-27 | 3181 |

| 2027-28 | 3146 |

| 2028-29 | 3001 |

| 2029-30 | 2528 |

| 2030-31 | 2369 |

| 2031-32 | 2305 |

| 2032-33 | 1840 |

| 2033-34 | 1591 |

| 2034-35 | 1416 |

| 2035-36 | 1023 |

| 2036-37 | 520 |

| 2037-38 | 306 |

The Planning Ministry immediately came up with a clarification of the news report, claiming that it was “based on incorrect information, baseless assumptions and biased analysis.” [xlv] It claimed that the Pakistan government liability was “only” US$6 billion in debt taken for infrastructure projects and the rest of the loans were taken by private investors and therefore the CPEC would not impose “any burden with respect to loans repayment and energy sector outflows.”[xlvi] The official statement, however, obfuscated the fact that the projects were all guaranteed by the government to provide foreign currency for debt repayment by the investors. Further, these projects were given preferential treatment in terms of tax exemptions (which would cost the Pakistan exchequer around US$4.5 billion) and were assured timely payments of dues through the instrument of a revolving account to prevent any circular debt. Rebutting the government argument, the reporter who revealed the total outflow on CPEC account disclosed that out of the US$40 billion, US$7.5 billion would be paid by the government for the loan it took for infrastructure projects, US$20 billion would be paid to Chinese financial institutions by the investors (money that Pakistan would ensure was made available) and around US$11.5 for investors to power projects.[xlvii]

Interestingly, the sheer opacity of the entire funding plan of the CPEC loans and investment can be gleaned from the discrepancy in the statements issued by the two governments to dispel the impression of Pakistan being ensnared in debt-trap diplomacy. In October 2018, Pakistan’s Ministry of Planning stated that 22 projects worth US$28 billion had been actualised.[xlviii] However, when in December 2018, the report of the US$40-billion pay-out came out, the Chinese embassy in Islamabad issued a press release giving a financial run-down for the 22 projects. According to the fact sheet, the total amount involved was US$18.8 billion[xlix] – or some US$10 billion less than what Pakistan was claiming.

Pakistan’s growing indebtedness to China is only one part of the picture. Over the years, despite strenuous efforts to attract foreign investment, Pakistan has been largely ignored. Its so-called strategic location as the bridge between South, Central and West Asia has failed to impress investors. Except for 2007 when a big infusion of foreign investment was made mostly in the telecommunications sector, Pakistan remains largely outside the radar of foreign investors. Not only has foreign direct investment (FDI) been low in the last 10 years – while India was attracting US$40 billion,[l] the inflow to Pakistan was under US$2 billion, and increasingly limited to a single country, i.e., China. Over the last few years, the Chinese investment in Pakistan forms the largest component of total FDI.[li] Other countries appear to have no interest in Pakistan, and in fact many companies have shut shop and exited Pakistan.[lii]

Data of the last two decades reveal that in the 10 years from 1997-2007/08, the US was a big investor in Pakistan. However, in the last five years, the US FDI has been falling while China’s FDI has risen, outstripping the US. This is understandable, as this was also the period in which China initiated the CPEC project. Pakistan and China have both been declaring various figures on the amounts of investment that have been made. China says the entire CPEC investment is expected to be around US$60 billion over three phases, and that anything between US$16-22 billion has already been invested. The numbers, however, in Pakistani official documents are far lower. According to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) data on net FDI, China has invested only around US$5 billion, nowhere close to China’s official numbers. In fact, by September 2016, while both Pakistani and Chinese officials were claiming that US$14 billion had been invested over 2015 and 2016,[liii] official Pakistani data show only US$2 billion in investment were in fact made in that period (and not all of it from China). In the five years from 2013-14 to 2017-18, the US FDI was recorded by the Board of Investment (BOI) at around US$700 million. (See Table 9.)

Table 9.

| NET FDI IN PAKISTAN (US$ Million) | |||

| USA | CHINA | ||

| Year | |||

| 1998 | 320.8 | 24.3 | |

| 1999 | 226 | 19.8 | |

| 2000 | 146.9 | 10.5 | |

| 2001 | 54.9 | 0.1 | |

| 2002 | 324.7 | 0.3 | |

| 2003 | 222.6 | 3 | |

| 2004 | 259.8 | 14.3 | |

| 2005 | 373 | 0.4 | |

| 2006 | 820.5 | 1.7 | |

| 2007 | 1766.8 | 712.1 | |

| 2008 | 1748.8 | 13.7 | |

| 2009 | 427.4 | -101.4 | |

| 2010 | 468.3 | -3.6 | |

| 2011 | 238.1 | 47.4 | |

| 2012 | 227.7 | 126.1 | |

| 2013 | 227.1 | 90.6 | |

| 2014 | 212.1 | 695.8 | |

| 2015 | 223.9 | 319.1 | |

| 2016 | 13.2 | 1063.6 | |

| 2017 | 44.6 | 1211.7 | |

While Chinese data on FDI in Pakistan is scarce, its National Bureau of Statistics has data on the turnover of economic cooperation projects—which includes contracted projects, labour cooperation, and design consultation (See Table 10).

Table 10.

The above numbers from Chinese official data indicate the country’s deepening involvement in economic projects in Pakistan, as well as the steady rise of Chinese workers and labour working in Pakistan. Meanwhile, details of the investments and contracts that Chinese companies have undertaken in Pakistan are available from the Chinese Investment Tracker of the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation. According to this data, since 2005, Chinese investments and contracts in Pakistan amount to around US$51 billion. Further, out of the US$51 billion, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) contracts and investments which commenced from 2013 are around US$40 billion, with almost US$32 billion in contracts and US$7.5 billion in investments (See Table 11). In fact, all the investments and contracts since December 2013 are in the BRI/CPEC basket.

Table 11.

| China Global Investment Tracker | ||||

| Year | Month | Chinese Entity | Quantity in Millions | Sector |

| 2005 | December | China National Nuclear | $490 | Energy |

| 2006 | September | Huawei | $550 | Technology |

| 2006 | November | China Communications Construction | $490 | Transport |

| 2007 | January | China Mobile | $280 | Technology |

| 2007 | February | Shanghai Shengong, Shanghai Municipal Government | $100 | Utilities |

| 2007 | May | China Mobile | $180 | Technology |

| 2007 | May | Sinomach | $150 | Energy |

| 2008 | November | Three Gorges | $320 | Transport |

| 2009 | February | Three Gorges | $180 | Real estate |

| 2009 | November | Harbin Electric | $600 | Energy |

| 2009 | December | China Mobile | $500 | Technology |

| 2010 | February | Three Gorges | $120 | Transport |

| 2010 | March | Sinomach, Gezhouba | $2,690 | Energy |

| 2010 | July | Sinomach | $160 | Energy |

| 2010 | July | Sinohydro | $110 | Energy |

| 2010 | December | China Communications Construction | $160 | Logistics |

| 2010 | December | China Communications Construction | $280 | Transport |

| 2011 | April | State Construction Engineering | $450 | Transport |

| 2011 | September | United Energy | $750 | Energy |

| 2011 | October | Three Gorges | $240 | Energy |

| 2011 | December | Three Gorges | $130 | Energy |

| 2012 | February | Three Gorges | $270 | Agriculture |

| 2012 | May | United Energy | $200 | Energy |

| 2012 | August | State Construction Engineering | $230 | Tourism |

| 2012 | November | Huawei | $500 | Technology |

| 2013 | January | China Communications Construction | $300 | Energy |

| 2013 | January | Three Gorges | $260 | Logistics |

| 2013 | August | Three Gorges | $1,650 | Energy |

| 2013 | December | China Communications Construction | $100 | Logistics |

| 2014 | January | Power Construction Corp | $240 | Energy |

| 2014 | February | China Communications Construction | $230 | Transport |

| 2014 | March | Shandong Ruyi | $120 | Other |

| 2014 | March | Three Gorges | $900 | Energy |

| 2014 | March | China Communications Construction | $220 | Transport |

| 2014 | April | China Mobile | $520 | Technology |

| 2014 | April | China Communications Construction | $130 | Transport |

| 2014 | June | Tebian Electric Apparatus | $190 | Energy |

| 2014 | August | Power Construction Corp | $130 | Energy |

| 2014 | August | China National Chemical Engineering | $240 | Energy |

| 2014 | September | Power Construction Corp | $1,300 | Energy |

| 2014 | September | Sinomach | $1,130 | Energy |

| 2014 | November | China Energy Engineering | $140 | Transport |

| 2014 | December | Sinomach | $100 | Energy |

| 2014 | December | China National Nuclear | $6,500 | Energy |

| 2015 | February | Huaneng and Shandong RuYi | $1,810 | Energy |

| 2015 | March | China Railway Construction, China Energy Engineering | $160 | Transport |

| 2015 | April | Power Construction Corp | $1,070 | Energy |

| 2015 | June | China Railway Corp and Norinco | $1,620 | Transport |

| 2015 | August | Power Construction Corp | $120 | Energy |

| 2015 | August | ZTE | $1,440 | Energy |

| 2015 | September | Harbin Electric | $1,100 | Energy |

| 2015 | October | Sinomach | $150 | Energy |

| 2015 | November | Zhuhai Port Holdings, State Construction Engineering | $1,620 | Transport |

| 2015 | December | China Railway Construction | $1,460 | Transport |

| 2015 | December | State Construction Engineering | $2,890 | Transport |

| 2015 | December | Power Construction Corp | $100 | Energy |

| 2016 | January | China Energy Engineering | $360 | Energy |

| 2016 | January | Three Gorges | $2,400 | Energy |

| 2016 | January | China Communications Construction | $1,320 | Transport |

| 2016 | January | Power Construction Corp | $220 | Transport |

| 2016 | April | Power Construction Corp | $910 | Energy |

| 2016 | June | China Communications Construction | $190 | Energy |

| 2016 | July | Three Gorges | $220 | Energy |

| 2016 | July | China Energy Engineering | $530 | Energy |

| 2016 | December | State Grid | $1,760 | Energy |

| 2017 | January | China Energy Engineering | $1,720 | Energy |

| 2017 | February | China Mobile | $200 | Technology |

| 2017 | February | China National Building Material | $130 | Real estate |

| 2017 | February | Power Construction Corp | $130 | Energy |

| 2017 | March | State Power Investment | $1,480 | Energy |

| 2017 | July | State Construction Engineering | $380 | Transport |

| 2017 | August | Minmetals | $200 | Energy |

| 2017 | September | China Railway Engineering | $100 | Transport |

| 2017 | September | Sinomach | $520 | Energy |

| 2017 | September | China Communications Construction | $140 | Transport |

| 2018 | March | Alibaba | $180 | Finance |

| 2018 | April | Alibaba | $150 | Other |

| 2018 | April | Harbin Electric | $280 | Energy |

| 2018 | May | Sinomach | $260 | Energy |

| TOTAL contract + investment | $51850 | |||

| BRI contract + Investment | $39510 | |||

| BRI Contracts | $31880 | |||

| BRI Investments | $7630 | |||

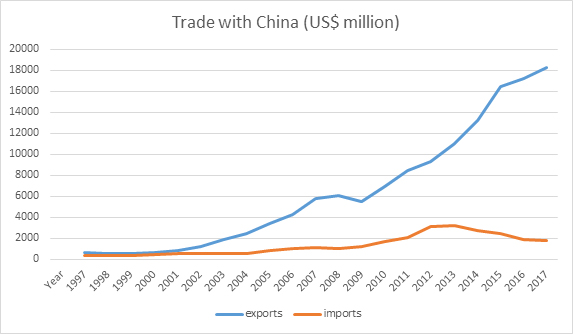

Perhaps the most crucial aspect of China’s growing economic domination in Pakistan is the lopsided trade between the two countries. Over the years, China has become Pakistan’s largest trading partner and controls over 30 percent of Pakistan’s foreign trade. In the two decades since 1997-98, China’s exports to Pakistan have risen dramatically and many Pakistani economists and businesses complain that Pakistan is facing de-industrialisation as the domestic market gets flooded by Chinese goods. Until the turn of the 21st century, the trade between the two countries was largely balanced; the gap started widening from around 2001. After the two countries signed the Free Trade Agreement in 2006, there was a dramatic rise in Chinese exports while Pakistan’s exports rose slowly (See Table 12 and Graph 5). Even more significant is the difference in the export figures released by China and the corresponding import figures released by Pakistan. For instance, in 2016 and 2017, the difference was almost US$8 billion. Although Pakistan has been trying to get more fairer terms with China in the phase 2 of the FTA negotiations, China has been unwilling to give any significant concession to far to their so-called “all weather friend”.[lvii]

Table 12.

| Trade with China (US$ million) | ||

| exports | imports | |

| Year | ||

| 1997 | 689.23 | 379.11 |

| 1998 | 523.76 | 389 |

| 1999 | 580.61 | 390 |

| 2000 | 670.32 | 492.18 |

| 2001 | 815.08 | 581.87 |

| 2002 | 1242 | 585 |

| 2003 | 1854.99 | 574.94 |

| 2004 | 2465.79 | 594.75 |

| 2005 | 3427.66 | 833.17 |

| 2006 | 4239.37 | 1007.21 |

| 2007 | 5789.05 | 1104.22 |

| 2008 | 6051.07 | 1006.8 |

| 2009 | 5528.33 | 1260.01 |

| 2010 | 6937.6 | 1731.02 |

| 2011 | 8439.71 | 2118.62 |

| 2012 | 9275.39 | 3138.25 |

| 2013 | 11019.6 | 3196.84 |

| 2014 | 13244.48 | 2753.87 |

| 2015 | 16441.89 | 2474.76 |

| 2016 | 17234.46 | 1912.59 |

Graph 5.

Compared to that of China, Pakistan’s trade with the US is not only more balanced but is also more in favour of Pakistan. In fact, the US is one of Pakistan’s largest export markets. However, unlike its trade with China, Pakistan’s trade with the US has been largely static over the years (See Table 13 and Graph 6). Pakistan’s dependence on the US and other Western markets is critical, and the remittances that overseas Pakistanis send from the West is what is keeping the economy afloat. This gives a leverage to the US and its Western allies to put pressure on Pakistan. But whether such pressure can pry Pakistan out of China’s embrace is questionable. One reason for this is the strategic and security relationship between the two ‘Iron Brothers’. Even on the economics front, China has managed to embed itself so deeply that Pakistan will find it extremely difficult to free itself from such state of dependency.

Table 13.

| Trade with US ($ million) | ||

| Year | Exports | Imports |

| 2001 | 2246 | 566 |

| 2002 | 2258 | 688 |

| 2003 | 2617 | 735 |

| 2004 | 2944 | 1329 |

| 2005 | 3447 | 1563 |

| 2006 | 4193 | 1657 |

| 2007 | 4183 | 2304 |

| 2008 | 3740 | 1503 |

| 2009 | 3540 | 1160 |

| 2010 | 3561 | 934 |

| 2011 | 4102 | 1120 |

| 2012 | 3949 | 789 |

| 2013 | 3887 | 1018 |

| 2014 | 3952 | 1126 |

| 2015 | 3961 | 1197 |

| 2016 | 3717 | 1480 |

| 2017 | 3685 | 2102 |

| 2018 | 3862 | 2076 |

Graph 6.

China today exercises a vice-like grip on Pakistan. Not only is Pakistan completely dependent on China for diplomatic and political support in international forums, and for meeting its critical defence needs, but China is also virtually the only economic avenue available for Pakistan. If the Pakistani rhetoric is anything to go by, the CPEC is their economic lifeline, their only hope for the future. That CPEC might actually be the biggest mill-stone around Pakistan’s neck is something that most Pakistanis are not even willing to consider. While the new political dispensation in Pakistan, after assuming office, did make some statements about re-examining the CPEC and resetting its priorities, even they have balked at taking on China. There is also hope being harboured by some Pakistani analysts and economists, that instead of Pakistan, it is China which will be caught in a bind. As the argument goes, if China does not want to lose the money it has invested in CPEC, then it must bail Pakistan out by giving it the free lunch that Pakistan used to get from the US.[lx] It remains to be seen how China will tackle this situation.

For now, China seems to be adopting a multi-pronged approach. In the public domain, it is doubling down on its support for Pakistan. All the statements from Chinese officials and leaders about their abiding commitment to their all-weather friendship with Pakistan and to CPEC, in part because any negative fallout on CPEC could impact other BRI projects.[lxi] Behind the scenes, however, the first cracks appear to have emerged in the relationship. China was already concerned over the talk by the Imran Khan government to re-think and review some of the CPEC projects. They were reportedly furious over an interview to the Financial Times given by Imran Khan’s de facto commerce minister, Abdul Razak Dawood, who complained about the unfairness of CPEC projects and wanted them to be put on hold for a year and perhaps even stretch them over five years.[lxii]

Within days of this interview, the Pakistan Army Chief had to rush to Beijing and avert a worsening of the situation.[lxiii] In their own veiled way, the Chinese leadership warned the Pakistanis against questioning the CPEC. President Xi Jinping told the Pakistan Army Chief, “As long as high-degree mutual trust and concrete measures are in place, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor construction will succeed and deliver benefits to people of the two countries.”[lxiv] Given the parlous state of finances, the Army Chief is also believed to have sought money from China. Later, Prime Minister Imran Khan visited China, expecting a big bailout package. After the visit, there was speculation that China was going to give US$6 billion in aid – US$1.5 billion grant, another US$1.5 billion loan and the remaining US$3 billion in CPEC-related assistance.[lxv] It was also reported that Imran Khan had asked for US$6 billion in cash – US$1.5 billion as deposit in State Bank of Pakistan, another US$1.5 billion as grant and US$2-3 billion as a soft loan.[lxvi] Later, it transpired that what was referred to in the media as a “historic” visit of Imran Khan had resulted in virtually no visible gain for Pakistan. China pressed Pakistan to operationalise the currency-swap agreement that was already a few years old and was not being used by Pakistani traders.[lxvii] This is something that China has been pushing hard in Pakistan and even have demanded that Chinese currency be allowed as legal tender in Gwadar Free Trade zone, something that had been refused by Pakistan at the time it was made, but could become a reality as the financial grip of China continues to tighten.[lxviii] In addition, they agreed to increase imports from Pakistan by US$1 billion. A few weeks later, it was reported that China had agreed to give Pakistan US$2 billion loan but at an interest rate of eight percent.[lxix] Clearly, even as China continues to say seemingly all the right things in public, behind the scenes, they are now starting to pull the noose around Pakistan’s neck. In mid-2018, when the Balance of Payments crisis was looming on the horizon, the chief economist of the Pakistan Planning Commission expressed confidence that with a few adjustments and better negotiations with China, Pakistan would be able to get enough to tide over any crisis. At that time, a former State Bank of Pakistan governor had warned: “How delusional can you get? I don’t buy the rhetoric of deeper than the Arabian Sea and higher than the Himalayas’ friendship. China will demand nothing less than real assets in return for a bailout.”[lxx]

As far as the US is concerned, it is perhaps only nostalgia of an era long gone that makes top officials think they can claw back some influence with Pakistan by continuing with their economic and military assistance. Apart from the fact that the Pakistanis do not mind US freebies but abhor the quid pro quo that the US seeks. The way Pakistan sees it, the US assistance while welcome is hardly of a magnitude that will make them rethink and recalibrate their relations with China. This means that the US will literally have to outmatch China dollar for dollar, if it has to have any hope of regaining significant influence with Pakistan. But if the US was to get into a competition against China to woo Pakistan, the only one to gain would be Pakistan. Worse, in that event, Pakistan would be even less amenable to any kind of reform. Given the deep-seated suspicion and animosity that most Pakistanis harbour for the US, it is more likely that even as the Pakistanis party on US aid and trade, they will neither be beholden to the US, nor will they lessen their ardour for their ‘all weather friends’.

Instead of restoring economic and military aid and trade to counter China, a more effective and also economical strategy would be to exploit the emerging fault-lines between China and Pakistan. The debt-trap diplomacy of China, its predatory trade policies and the negative economic impact Chinese investment practises on local businesses can be exploited to rust the relationship between the two ‘Iron Brothers’. The Americans still exercise enormous economic leverage over Pakistan, not just in terms of bilateral aid and trade, but even more through their influence in both Multilateral Financial Institutions like IMF, World Bank and ADB, and the rest of the West which generally follows the US’ lead (see Table 14 and Graph 7).

Table 14.

Graph 7.

The US remains critical for Pakistan not because it is the patron-in-chief of that country – that place has been taken by China. But China still does not have the comparable international financial and trading ecosystem that the US has, and on which Pakistan is dependent for its economic survival. Quite simply put, when the US engages a country like Pakistan, it also opens the floodgates of aid and trade flows from other Western countries that follow the US’ lead. While Pakistan can do without the aid, it is in need of the trade.[lxxii] From Graph 7 and Table 14, the correlation between US aid and that of other Western countries is quite apparent. This is a leverage that the US can bring to bear to drive a wedge between China and Pakistan. Alongside, Chinese treatment of Muslim minorities can also become a tool for driving a wedge between the two countries.

While it is apparent that Pakistan’s dependence on China has surpassed its dependence on the US, the hard reality is that while the US cannot match China dollar for dollar in Pakistan, China also does not have the power to rescue Pakistan if the US starts to turn the screws hard on Pakistan. An equally difficult reality is that it is far from clear if the US even understands its power and influence – including the fact that no self-respecting Pakistan general, bureaucrat, politician or businessman wants their kids to study or settle in China as compared to the West. There is also the all-important question of whether the US even wants to exercise the hard, coercive and non-kinetic power it wields, or would rather continue playing soft-ball with Pakistan. Counter-intuitive though it may seem, the fact of the matter is that the more the US continues with the soft approach, the more it pushes Pakistan into China’s embrace and the lower the incentive or disincentive for Pakistan to change its behaviour and policies; conversely, the smart exercise of hard, non-kinetic power has greater potential to force compellence on Pakistan while driving a cleavage in its relations with China.

[i] https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/947802588174577664?lang=en

[ii] “US to hold Pak aid till decisive action against terrorists”, The News International, 03/01/2018.

[iii] Aamir Khan, “Pakistan decides to review ties with Washington”, Express Tribune, )2/01/2018.

[iv] “Asif shrugs off aid suspension”, The Nation, 05/01/2018.

[v] “We don’t need security aid at the cost of national dignity: DG ISPR”, Express Tribune, 05/01/2018.

[vi] Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Geng Shuang’s Regular Press Conference on January 2, 2018, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China.

[vii] Khalid Mustafa, “US assistance no more needed, says Miftah”, The News International, 02/01/2018.

[viii] Anwar Iqbal, “Washington leverage not as big as US believes, says report”, Dawn, 17/01/2018.

[ix] U.S. Foreign Assistance To Pakistan, Hearing before the Subcommittee On International Development and Foreign Assistance, Economic Affairs, and International Environmental Protection of the Committee On Foreign Relations, United States Senate, One Hundred Tenth Congress, First Session, December 6, 2007.

[x] Max Frost, “How to bail out Pakistan and augment American leverage”, The Diplomat 26/09/2018.

[xi] Naveed Ahmad, “The swelling nexus against US sanctions”, Daily Pakistan 20/08/2018.

[xii] Zaheer Abbasi, Tahir Amin & Nuzhat Nazar, “Actions could cause consequences over long term only”, Business Recorder 07/01/2018.

[xiii] Monographs – zarb-e-Azb, Lal Masjid, on CPEC Chinese Ambassador

[xiv] Atif Khan, “Pakistan asks China to soften restrictions on Muslims”, The Nation 20/09/2018.

[xv] Jamil Anderlini, Henny Sender and Farhan Bokhari, “Pakistan rethinks its role in Xi’s Belt and Road plan”, Financial Times 09/09/2018.

[xvi] This was a conversation between an Indian diplomat in Islamabad with a senior Pakistan Army official and was revealed to the author by a top Indian official dealing with Pakistan.

[xvii] Chinese backing in NSG, on Masood Azhar are two examples.

[xviii] Foreign Minister Khawaja Asif interview to Shahzeb Khanzada, Geo TV 05/09/2017.

[xix] Anwar Iqbal and Iftikhar A. Khan, “Trump’s tweet on Pakistan sparks war of words”, Dawn 02/01/2018.

[xx] Dr Mohan Malik, “The China factor in India-Pakistan conflict”, Occasional Paper Series, Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies, November 2002.

[xxi] Mohammed Ahsen Chaudhri, “Strategic And Military Dimensions In Pakistan-China Relations”, Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, Pakistan Horizon, Vol. 39, No. 4, Focus on: Sino-Pakistan Relations (Fourth Quarter 1986), pp. 15-28; also see John Hayward, “John Bolton: ‘There Wouldn’t Be a Pakistani Nuclear Weapons Program Without China’“, Brietbart 25/08/2017.

[xxii] ‘Pakistan’s Sanction Waivers: A Summary’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 29/10/2001.

[xxiii] Source: SIPRI Arms Transfer database on 02-10-2018; All figures are SIPRI Trend Indicator Values (TIVs) expressed in millions

[xxiv] See table 4

[xxv] Source: Ministry of Finance, Government of Pakistan, Annual Budget Documents, Estimates of Foreign Assistance, various years

[xxvi] Shahbaz Rana, “Terror war losses outstrip ‘generous’ US payments”, Express Tribune 03/01/2018.

[xxvii] Mehtab Haider, “Pakistan got $15 bn for its services, logistic support”, The News International 02/01/2018.

[xxviii] Mehtab haider, “Fact checking Trump: US disbursed just $1.88 billion to Pakistan in 10 years”, The News International 04/01/2018.

[xxix] Mehtab Haider, “US withheld amount equal to Pakistan’s one-day expense: Miftah”, The News International 04/01/2018.

[xxx] Source: Susan B. Epstein & K. Alan Kronstadt, “Pakistan: US Foreign Assistance, April 10, 2012, CRS Report for Congress; Note: Military assistance from 2012 includes CSF funding; 2018 figures are requisitions, all others are appropriations; For Pakistani claims see Mubarak Zeb Khan, “Pakistan received $5bn in civilian aid since 2001, Government finds“, Dawn 06/01/2018.

[xxxi] Source: Pakistan Economic Survey Statistical Supplement various years; all figures in US $ million

[xxxii] Dreher, A., Fuchs, A., Parks, B.C., Strange, A. M., & Tierney, M. J. (2017). Aid, China, and Growth: Evidence from a New Global Development Finance Dataset. AidData Working Paper #46. Williamsburg, VA: AidData.

[xxxiii] Source: Handbook of statistics on Pakistan economy 2015, Page 865-71, State Bank of Pakistan; Also SBP Annual Report Statistical Supplement FY17, page 96-97; Note: Data for 2014-17 includes China SAFE deposits, money lent to State Bank of Pakistan to bolster the foreign exchange reserves.

[xxxiv] Natasha Turak, “Pompeo spotlights Pakistan as latest tension point between Washington and Beijing”, CNBC.com 31/07/2018.

[xxxv] Ibid.

[xxxvi] Drazen Jorgic, “Pakistan dismisses U.S. concerns about IMF bailout and China”, Reuters 01/08/2018.

[xxxvii] Muhammad Zamir Assadi, ‘Accusing CPEC of being a debt trap for Pakistan false and baseless’, China Daily 26/10/2018.

[xxxviii] Adnan Amir, ‘The CPEC and Pakistan’s Foreign Debt Problem’, 03/7/2018.

[xxxix] Salman Siddiqui, “Pakistan will be paying China $90b against CPEC-related projects”, Express Tribune 12/03/2017.

[xl] Source: Economic Affairs Division, Ministry of Finance, Government of Pakistan, (various years); Note: (1) Included in the disbursement data; (2) Commercial Bank loans for BOP support

[xli] Tom Hussain, ‘Pakistan wrestles with growing ‘Chinese corridor’ debt’, Nikkei Asian Review 27/3/2017.

[xlii] Mubarak Zeb Khan, ‘CPEC repayment plan under preparation’, Dawn 12/8/2018.

[xliii] Shahbaz Rana, ‘Pakistan to pay China $40b on $26.5b CPEC investments in 20 years’, Express Tribune 26/12/2018.

[xliv] Ibid.

[xlv] ‘Ministry Of Planning Clarifies A News Article On CPEC Debt’, Ministry of Planning, Government of Pakistan.

[xlvi] Ibid.

[xlvii] Shahbaz Rana, ‘Govt to provide forex for CPEC debt repayment’, Express Tribune 28/12/2018.

[xlviii] ‘Ministry Of Planning Clarifies Western Media Fresh Report On CPEC’, Ministry of Planning, Government of Pakistan.

[xlix] ‘Financing run-down of 22 CPEC projects’, Embassy of China, Islamabad, 29/12/2018; Also see ‘Statement from Chinese embassy’, 29/12/2018.

[l] Financial Year-Wise Fdi Inflows Data

[li] Naveed Butt, “FDI in Pakistan: China now top investing country”, Business Recorder 02/04/2017.

[lii] Farooq Hasan, ‘Pakistan and the multi-nationals’, Business Recorder 06/11/2016.

[liii] ‘China has so far poured $14b into CPEC projects’, Express Tribune 27/9/2016.

[liv] Source: Handbook of statistics on Pakistan economy 2015, State Bank of Pakistan, Page 776-82 for years 1998-2009; also Board of Investment, Prime Minister Office, Islamabad for years 2010-2018.

[lv] Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, — different years

[lvi] Source: American Enterprise Institute.

[lvii]“Pakistan guns to complete China FTA by December”, Dawn 26/09/2018.

[lviii] Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, — different years; Also Ministry of Commerce, Peoples Republic of China

[lix] Source: Pakistan Economic Survey, Statistical Supplement (various years)

[lx] Senator Nauman Wazir Khattak in Spotlight Aaj Tv 22/10/2018.

[lxi] Liu Zhen, ‘China, Pakistan can resolve investment problems, but ‘belt and road’ concerns should not be ignored, experts say’, South China Morning Post 10/9/2018.

[lxii] Jamil Anderlini, Henny Sender and Farhan Bokhari, ‘Pakistan rethinks its role in Xi’s Belt and Road plan’, Financial Times 09/9/2018.

[lxiii] ‘Lets nip that in the bud’, Business Recorder 01/10/2018.

[lxiv] ‘Xi says China places ‘high premium’ on Pakistan ties’, Dawn 21/9/2018.

[lxv] ‘Chinese coffers’, Daily Times 04/11/2018.

[lxvi] Mariana Babar & Mehtab Haider, ‘Balance of payments crisis over: Asad Umar’, The News International 07/11/2018.

[lxvii] Khurram Hussain, ‘Yuan proposal puzzles financial circles’, Dawn 20/12/2017.

[lxviii] Shahbaz Rana, ‘Pakistan rejects use of Chinese currency’, Express Tribune 21/11/2017.

[lxix] ‘China to lend Pakistan $2 billion’, The News International 02/1/2019.

[lxx] Afshan Subohi, ‘Pakistan keeps its options open’, Dawn 11/6/2018.

[lxxi] Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank.

[lxxii] Sushant Sareen, ‘Pakistan’s Economy: An unviable state’, in Satish Chandra & Smita Tiwari (Ed) “Insights into evolution of contemporary Pakistan”, Pentagon Press (2015), pp 120, 123

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sushant Sareen is Senior Fellow at Observer Research Foundation. His published works include: Balochistan: Forgotten War, Forsaken People (Monograph, 2017) Corridor Calculus: China-Pakistan Economic Corridor & China’s comprador ...

Read More +