Introduction

‘Vision 2030’ is an ambitious roadmap for Saudi Arabia’s transformation announced by Crown Prince and de-facto ruler Mohammed bin Salman in 2016. It involves social and economic reform strategies designed to achieve a diversified private sector-led economy, a healthy and vibrant society, and a more sustainable future.

The Vision intends to realise its goals by leveraging what it identifies as Saudi Arabia’s strengths:

- Leadership of the Arab and Islamic world

- Investment capacity

- Strategic geographic location at the confluence of Asia, Africa, and Europe

For an ambitious national transformation project like Vision 2030 to succeed, the principles of change management are indispensable. Change management is a structured approach to implementing change, to lessen the impact on people by preparing, equipping, and supporting them during the change. Without adoption, the changes will not deliver the desired outcomes.[1]

Most leading companies today[a] recognise the need for change management. Public sector activities, however, have been slower in incorporating change management, as found in research by the McKinsey Center for Government (MCG): less than one-third of public-sector transformation leaders have received any training in change-leadership skills.[2]

There are certain areas where change management can help in fulfilling the goals of a project as ambitious as Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. This includes the need to overcome structural inertia[b] before the plan can find wide social adoption.[3] Moreover, the changes would impact each stakeholder differently, i.e., those who can take advantage of the changes will profit from them while others who cannot, will stand to lose.[4] Projects also often fail because of implementation myopia—or execution without preparedness for end-user adoption. For most project managers, the primary focus is on the execution of the project instead of the outcome which lies outside their ambit, thereby often missing the stated objectives of the project.

Vision 2030: Ambit and Impact

Vision 2030 entails massive economic, social, and cultural changes.[5] The Council of Economic and Development Affairs (CEDA), presided by Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, is responsible for formulating and establishing the mechanisms for the plan’s execution. Eleven Vision Realization Programs (VRP) and the National Center for Performance Measurement are tasked with translating the strategic objectives into actionable projects and monitoring progress.[6]

An examination of the Human Capability Development Programme (HCDP)—one of the 11 VRPs—can help understand the monumental changes associated with the project. The programme’s goal is to prepare globally competitive citizens by instilling values, developing skills, and enhancing knowledge. This in turn requires an overhaul of the education system and labour market. Despite the high literacy and enrolment rate in Saudi Arabia, educational performance is amongst the lowest in the world. It ranks in the bottom 8 percentile in 4th Grade Maths and bottom 6 percentile in 4th Grade Science.[7] Amongst the GCC countries, Saudi Arabia ranked second lowest (based on reading, maths and science test scores).[8]

In terms of labour productivity, too, Saudi Arabia is lagging behind other emerging economies. Annual productivity growth over the high growth decade (2003-13) was 0.8 percent, far lower than the 3.3 percent recorded by other G20 emerging economies. Another peculiarity is Saudi Arabia’s dual labour market, where most Saudi nationals are employed in higher-paying public-sector jobs, and foreign workers dominate lower-paying private-sector jobs.[9] This has led to a situation where there are unemployed nationals who are unwilling or unable to participate in productive activities. Consequently, there is significant reliance on foreign labour. Low participation in the workforce is another significant problem especially for women, who had a dismal workforce participation rate of 18 percent in 2014.[10]

For Vision 2030 to be realised, those impacted must adapt to the new economic, social, and cultural realities that the plan entails. By assessing the impact and anticipating stakeholders’ reactions, change management techniques can hasten this process.

Economic Transformation

The Saudi Arabian economy is largely a rentier economy[c] that is sustained by the oil and gas sector. Most Saudi citizens work in the public sector while foreign workers account for 76 percent of the total employed population.[11]

The changing global energy trends and population explosion have rendered this system unsustainable. Keeping this in mind, Vision 2030 aims to transform the kingdom into a productivity-led economic system: more diversified, globally integrated, and private-sector-intensive. Enhancing the following key areas will help achieve this transformation.

- Macroeconomic factors: These include fiscal sustainability, improving the business environment, maximising investment capabilities, and streamlining government services.

- Encouraging private enterprise: The private sector is being encouraged to exploit new domains (such as mining, tourism, and transnational logistics) and attract Foreign Direct Investments (FDI). Policies for nurturing entrepreneurship and SMEs are being formulated.

- Human capital development: Programmes for citizens’ skill development, increasing attractiveness of private sector employment, encouraging skilled foreign talent, and increasing participation of women in the workforce are being initiated.

Categorising stakeholders (as given in Table 1) will help gauge the impact of a transformation on each section such as citizens, foreign workers, and the outside world.

Table 1. Economic Impacts of Vision 2030

| Stakeholders |

Citizens |

Foreign Workers |

External world |

| Expected impacts of Vision 2030 |

• Reduced subsidies and allowances.

• Need to be globally competitive.

• Change in nature of employment (public sector to private sector).[12]

• Opportunities for wealth creation.

• Higher workforce participation and lower unemployment.[13]

|

• Improved working and living conditions.

• Emphasis on high-skilled workers.

• Loss of opportunities for low-skilled workers.[14]

• Opportunities for investment and wealth creation.

|

• Increased opportunities for investments.

• Improved ease of doing business.

• Easier access to visit and travel.

|

Socio-cultural Transformation

Saudi Arabia is seen as a highly conservative country, and Vision 2030 aims to instil values of moderation and tolerance in the polity. Crucial legal reforms are underway to make the law more compatible with modern life.[15],[16] The ongoing policy reforms will have an impact on the following areas:

- Role of women in society: Social restrictions on women such as male guardianship are being removed to encourage their participation in the economy and society.[17]

- Cultural rejuvenation and Improvement of quality of life: Art, entertainment, and sports are getting a fillip through the quality-of-life programme (VRP), enhancing the lifestyle for citizens, residents, and visitors.

- National identity: A national identity, distinct from religious and ethnic identities is being built by focusing on national heritage, art, and culture.[18],[19]

Table 2. Impacts of Sociocultural Transformation

| Stakeholders |

Citizens |

Foreign Workers |

External world |

| Expected impacts of Vision 2030 |

• New cultural norms

• Previously unavailable art, entertainment and sports made available

• Drastic changes in women’s role in society

• Increased focus on citizens’ well-being including housing, health, and social welfare

• Significant changes to the legal system

• Increased nationalism

|

• Existing workers must adjust to socio-cultural changes

• More predictable legal environment

• Improvements in living conditions – new entertainment, culture and sports

• More opportunities for women workers

|

• New foreign policy direction with a focus on security in the kingdom[20]

• A more tolerant state as it moves away from Wahhabism[21]

• ‘Trendsetter’ for Islamic and Arab countries

• Increased opportunities to visit Saudi Arabia for religious and non-religious tourism

|

Recommendations

Since its announcement, Vision 2030 has been revised a few times; it has seen both successes and shortcomings. Key successes include a 122-percent increase in non-oil government revenue, an increase in citizens’ homeownership rate to 60 percent, and a rise in women’s workforce participation to 33.2 percent. The groundwork has also been laid for reforms in the financial markets and legal set-up.[22]

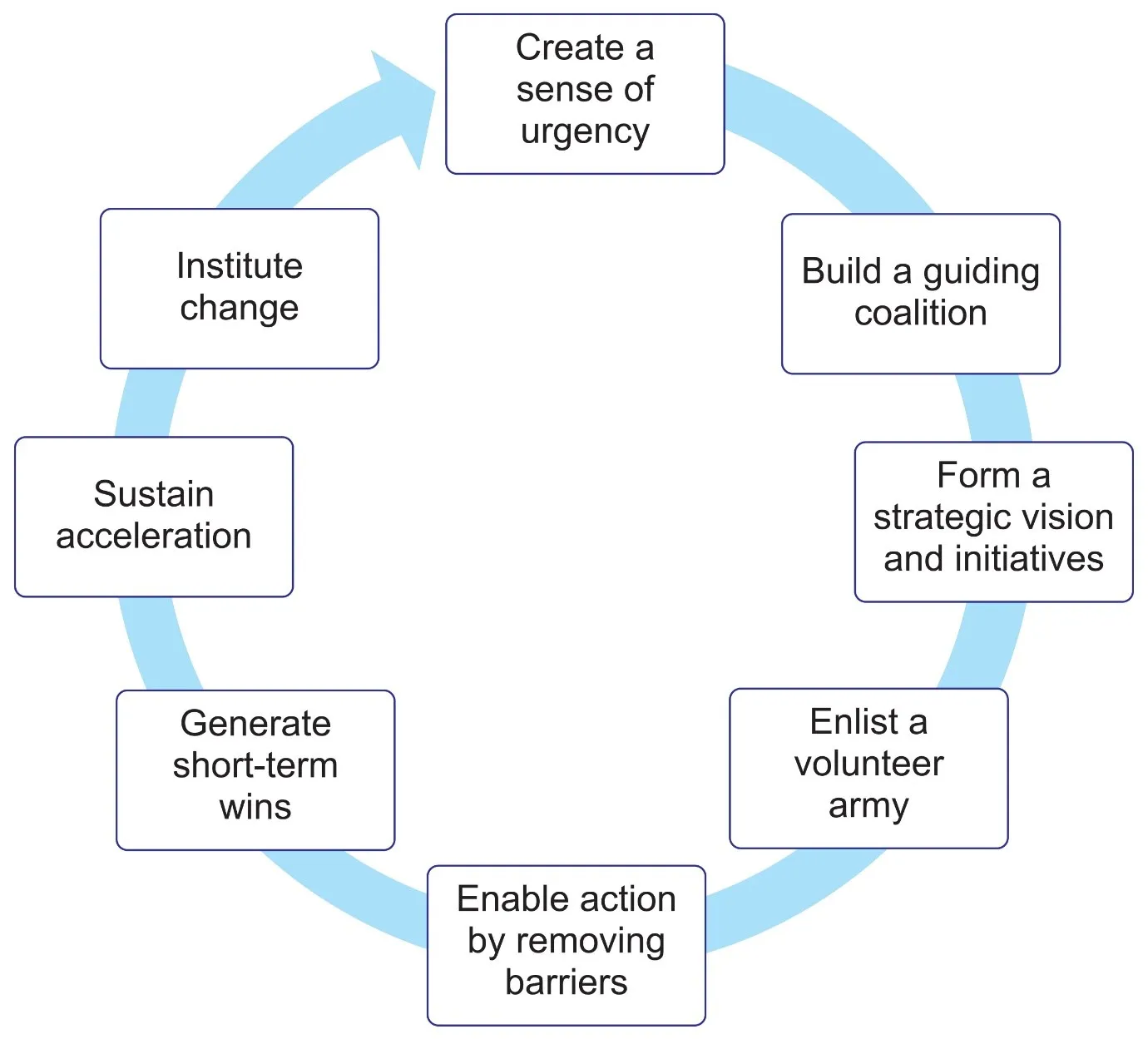

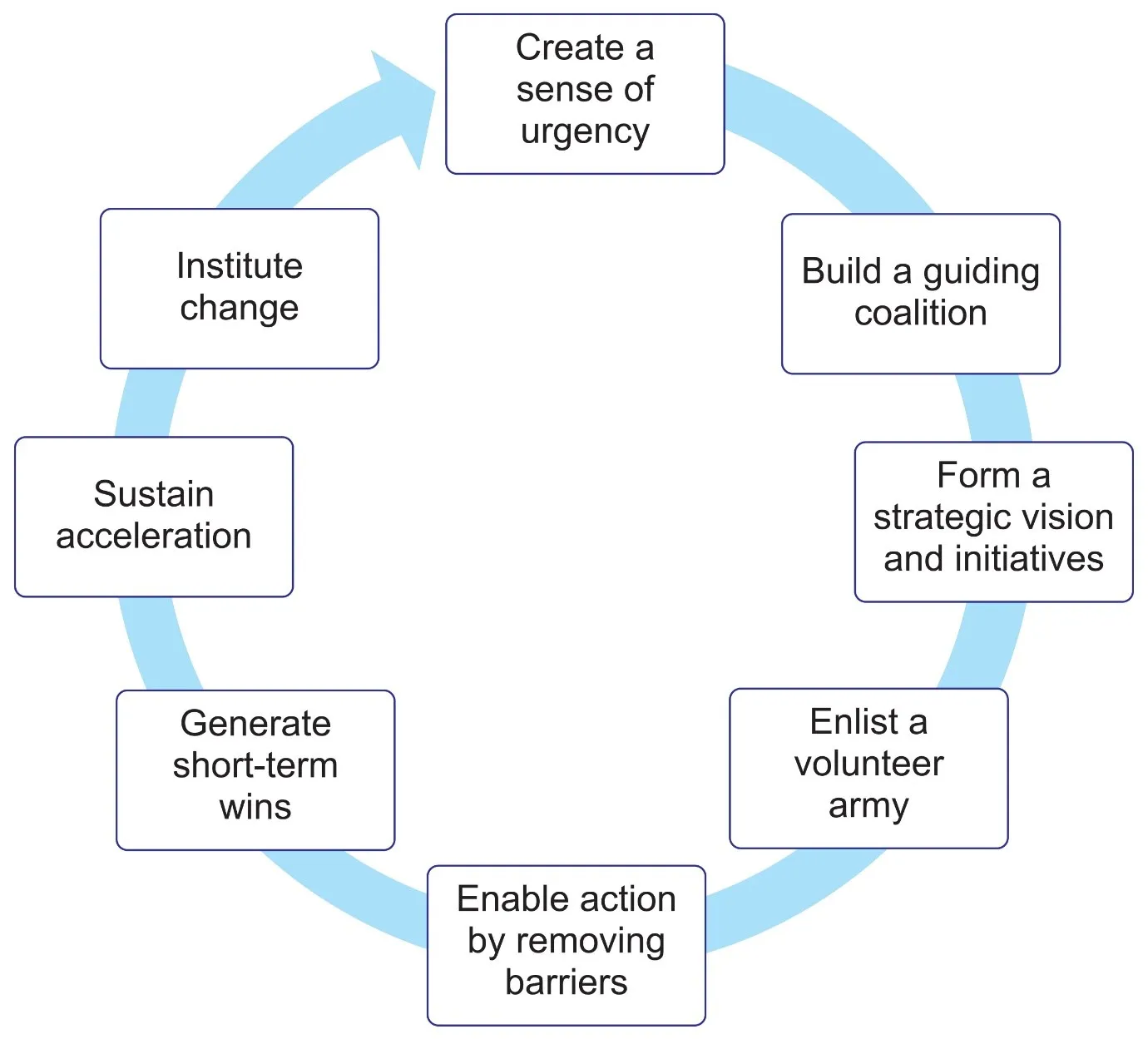

From a change management perspective, it is important to manage stakeholders’ reactions to change adoption. Anticipating stakeholders’ reactions allows leaders to develop a response to manage reactions. In his seminal work ‘Leading Change’, John Kotter outlines an eight-step process for successful change management (see Figure 1).[d]

Figure 1. The Fundamentals of Change Management

This framework is considered the gold standard for strategic management of organisational transformation. Vision 2030 scores exceptionally well here as each step is sequentially executed by the leadership. Uncomfortable changes are tedious and need to be explained to stakeholders as urgent and unavoidable. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has successfully communicated this by highlighting the unsustainability of the old order and providing an alternative for a better future.

Indeed, transformations are collective efforts that need institutional support. New power centres aligned with the Vision have been empowered to guide its execution. It is important to convey to stakeholders how the future will be different and how it can be realised through initiatives linked directly to the vision.

The Vision has found great support on social media, generating optimism especially amongst the youth who are rallying around a common opportunity. Results have been collected and communicated – early and often – not just to track progress but also to energise volunteers. New announcements of mega-projects such as the Line city or Oxagon of NEOM sustain the message and keep it in limelight. A culture of change has been instituted to the degree where it feels natural and inevitable, resulting in further buy-in from stakeholders.

Operationally, however, the change management approach for Vision 2030 execution has been sub-par. In current management practice, large-scale transformations typically have a change management team embedded in the executing body. So far, there is no agency tasked with change adoption or risk mitigation[23] for Vision 2030 realisation programmes. As there are hundreds of projects being executed as part of the vision, each needs to have a change management approach to sort avoidable problems.

For example, in 2016, austerity measures that were announced were not properly implemented. Public sector employees, who make up over two-thirds of all employed nationals saw their take-home pay slashed by up to 40 percent in a royal decree. This followed the reduction of subsidies on energy and water. The announcement came without warning and was met with substantial resistance. Just as unexpectedly, in April 2017, the pay cuts were revoked by royal decree and subsequently, in June 2017, were rolled back completely.[24] It is entirely predictable that rapid pay cuts in the absence of compensatory social welfare mechanisms will be met with resistance. By reversing its decision, the government would be sending mixed signals on its commitment to such measures and undoing its own narrative of urgent change.[25] Such incidents are easily avoidable by incorporating change management.

Change Adoption and Risk Mitigation

Change management techniques can significantly aid Vision 2030 outcomes. Four key attributes can be incorporated for maximising favourable outcomes:

- Set up a change management network: There is a need to establish hierarchy, define roles, and responsibility for a change management network—consisting of different nodules operating at different levels of programme execution.

- Design a methodology: Design an operational change management methodology that would be applied to each individual project to identify impacted stakeholders, map the scale and scope of change, plan resistance mitigation actions, and flag potential risks.

- Liaise with support functions: Liaise with other support functions for their expert inputs in solving mission-critical problems. Successful change management relies on building strong narratives and pre-emptive risk mitigation.

- Build feedback loops: Adoption to change is a long-term process. It has to happen organically and cannot be forced by simply putting in place the necessary infrastructure. The change management team is aptly placed to analyse user feedback and provide inputs to programme designers.

Conclusion

In early 2015, Saudi Arabia was confronted with the fact that the existing socio-economic model of ‘rentierism’ had become evidently unsustainable[26] and external events were straining it further. Policymakers could either reactively address each challenge as it unfolds or proactively lead the country through a socio-economic transformation.[27] Vision 2030 was, therefore, a bold new direction for Saudi Arabia.

A top-down, state-driven national transformation programme of the scale of Vision 2030 has never been tried before, and therefore comes with its own challenges.[28] Historically, the Saudi state has dominated the economy through its monopoly on oil resources. In contrast to western models where citizens produce a surplus and pay taxes, the Saudi system purchases political acquiescence by distributing unearned wealth to its citizens in the form of subsidies, jobs, infrastructure, and public services. By re-organising public spending and opening the economy to greater competition in the form of market forces, Vision 2030 would upend the existing economic order.

Culturally, too, Vision 2030 is changing long-term norms overnight. Institutions such as the Shariah courts, the Ministry of Education and the Committee for Promoting Virtue and Preventing Vice greatly influence everyday life. Recent reforms, such as legal reforms, for example,[29] have undercut these powerful actors. In re-branding[30] and reforming[31] them at a breakneck pace, policymakers are administering rapid cultural changes that could give rise to the possibility of resentment and resistance in some quarters. If not managed effectively, they could pose considerable risks to the success of Vision 2030.

The success of any transformation depends on grassroots adoption. After all, it is the citizens who lead the transformation of a nation. The success of Vision 2030 depends not just on mitigating risks but also on overcoming structural inertia, thereby enormously increasing the chances of transformational success. From an operational standpoint, there are four key attributes for successful change management:

- A change management network embedded in each part of the project execution body

- A standard operating methodology applicable to each of the hundreds of projects

- Collaboration with other support functions such as communication for propagating strong narratives

- A feedback loop to collect user inputs and refine programme design

At present, the Vision 2030 execution team does not have a structured change management approach incorporating all these attributes. If incorporated, it would greatly increase grassroots adoption while simultaneously minimising risks.

Aniruddha Sharma is a management professional with a keen interest in the geopolitics of business.

[a] Most Fortune500 companies including Apple, Google, Walmart have incorporated change management to their organisations and have dedicated teams to administer it.

[b] The tendency to maintain status quo and resist deviating from existing structural schemes is called structural inertia.

[c] A rentier state is a state that uses revenue generated through export of natural resources to fund vast networks of patronage and provide public services to its citizens.

See: Joseph Bahout, Perry Cammack, Jihad Yazigi, Steffen Hertog, Jane Kinninmont, Ishac Diwan, Fadi Ghandour, “Arab Political Economy: Pathways for equitable growth”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

[d] John P Kotter.

[1] “What is Change Management?”, Prosci.

[2] Martin Checinski, Roland Dillon, Solveigh Hieronimus, and Julia Klier, “Putting people at the heart of public-sector transformations”, McKinsey & Company, March 5, 2019.

[3] Rosabeth Moss Kanter, “Ten Reasons People Resist Change”, Harvard Business Review, September 25 2012.

[4] Matthew M Reed, “Saudi Vision 2030: Winners and Losers”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, August 02, 2016.

[5] Karen Elliott House, “Saudi Arabia in Transition”, Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, July 2017.

[6] Stephen Grand and Katherine Wolff, “Assessing Saudi Vision 2030: A 2020 review”, Atlantic council.

[7] “The Labor Market in Saudi Arabia”, Evidence for Policy Design at John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University.

[8] Harvard University, “The Labor Market in Saudi Arabia”

[9] Gassan Al-Kibsi, Jonathan Woetzel, Tom Isherwood, Jawad Khan, Jan Mischke, Hassan Noura, “Saudi Arabia Beyond Oil: The investment and productivity transformation”, McKinsey & Company, December, 2015.

[10] Al-Kibsi et al “Saudi Arabia Beyond Oil: The investment and productivity transformation”

[11] Françoise De Bel-Air, “Demography, Migration and Labour Market in Saudi Arabia“, The Gulf Labour Markets, Migration and Population (GLMM) programme, 2018.

[12] PWC Middle East, How Saudisation and Vision 2030 are shaping the Kingdom’s immigration landscape, PWC, June 20, 2021.

[13] Eman Alhussein, “Labor Reforms in Saudi Arabia: Ambitious Focus on Foreign Workers and Unemployment”, Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, March 17, 2021,

[14] “Saudi Arabia’s vision for future has little space for Indian workers”, The Economic Times, August 24, 2017.

[15] Natasha Turak, “Saudi Arabia announces major legal reforms, paving the way for codified law”, CNBC, February 9, 2021.

[16] “Crown Prince announces 4 new laws to reform Saudi Arabia’s judicial institutions”, Saudi Gazette, February 8, 2021.

[17] “Saudi Arabian women can now drive – here are the biggest changes they’ve seen in just over a year”, Business Insider, June 27, 2018.

[18] Desirée Custers, “Visiting Riyadh: a look at Saudi Arabia’s social and cultural transformations”, Stimson, March 25, 2022.

[19] Hassan Al-Mustafa, “Vision 2030 creating an inclusive Saudi identity”, Arab News, May 03, 2021.

[20] Jan Achakzai, “KSA resetting foreign policy, economy, society — lessons for Pakistan”, The News International, December 15, 2021.

[21] Iyad el-Baghdadi, “Mohammed bin Salman is the worst enemy of his ‘Vision 2030’ plan”, The Washington Post, June 15, 2018.

[22] Jane Kinninmont, “Vision 2030 and Saudi Arabia’s Social Contract”, Chatham House, July 20, 2017.

[23] Dr.Salman Al Marzouki, “The value of integrating Change Management and Project Management “Achieving the desired outcomes of Saudi Vision 2030 projects and initiatives in light of current COVID-19″”, Devoteam, February 03, 2021.

[24] Ivana Kottasová, “Saudi Arabia reverses pay cuts for state workers”, CNN Business, April 24, 2017.

[25] Emily Lawson and Colin Price, “The psychology of change management”, McKinsey & Company, June 01, 2003.

[26] Luay al-Khatteeb, “Saudi Arabia’s economic time bomb”, Brookings, December 30, 2015.

[27] Al-Kibsi et al., “Saudi Arabia Beyond Oil: The investment and productivity transformation”

[28] Mohammed Nuruzzaman, “Saudi Arabia’s ‘Vision 2030’: Will It Save Or Sink the Middle East?”, E-International Relations, July 10, 2018.

[29] Dr. Abdel Aziz Aluwaisheg, “Saudi legal reforms to follow international norms”, Arab News, May 21, 2021.

[30] Madawi al-Rasheed, “Mohammed bin Salman is taking risks by rewriting Saudi history”, Middle East Eye, February 21, 2022.

[31] Kamel Abderrahmani, “Mohammed Bin Salman attempts to reform Islam,” AsiaNews, August 05, 2021.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV