[a]As of 2017–18, 55.9 percent of the Afghan population live in poverty.

[b]The Human Development Index is a summary measure for estimating the long-term progress in three basic dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, access to knowledge, and a basic standard of living.

[c] India was the fifth-largest bilateral donor to Afghanistan in 2012, and the largest amongst the regional countries in 2015.

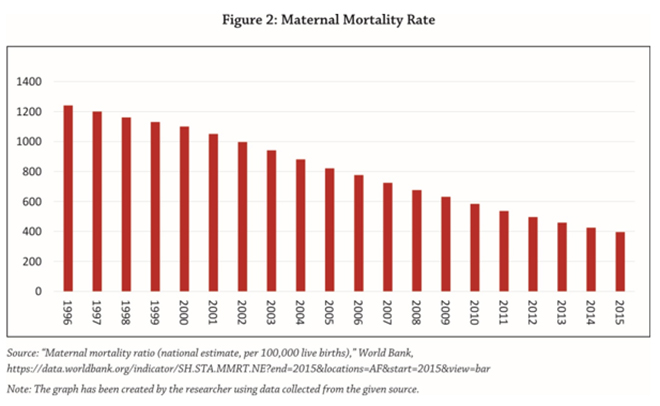

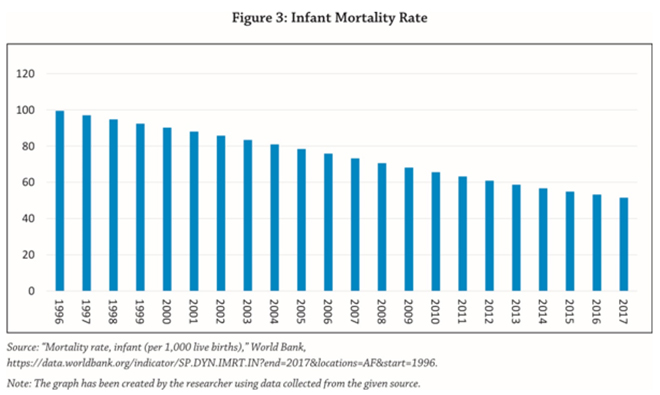

[d] There are apprehensions about the return of the Taliban because the health of women and children in Afghanistan had degenerated significantly during its regime (1996–2001) due to the group’s repressive principles, which are discussed later in this brief.

[e]Before the Taliban takeover, Afghanistan had suffered the Saur Revolution in 1978, the Soviet–Afghan War in 1979–89, and Afghan Civil War between the Government of Afghanistan and the Mujahideens in 1989–96.

[f] The Taliban followed an extreme brand of “deobandism” and, in some cases, were also inspired by Wahabism or Salafism, which sought to revive ancient Islamic values and impose Sharia law.

[g] Only the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan had recognised the Taliban rule in Afghanistan.

[h] While NGOs trained health workers in Afghanistan, some international health workers from international NGOs, e.g. Doctors Without Borders, also worked in the areas not dominated by the Taliban.

[i] The performance on the health level is measured as the ratio between achieved levels of health and the levels of health that could be achieved by the most efficient health system. The overall performance of the health system was measured using a similar process, by comparing achievement to expenditure.

[1] “Population in multidimensional poverty, headcount (%)”, Afghanistan Profile, Human Development Reports, United Nations Development Programme, 2019, http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/38606.

[2]“Afghanistan’s healthcare system struggles to rebound,” Aljazeera, 10 August 2016, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/08/afghanistan-health-care-system-struggles-rebound-160810104017464.html.

[3] For more details on the Human Development Index, see “Briefing note for countries on the 2018 Statistical Update: Afghanistan,” Human Development Indices and Indicators: 2018 Statistical Update, United Nations Development Programme, 2018, 1, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/AFG.pdf.

[4] “2019 Human Development Index Ranking,” Human Development Reports, United Nations development Programme, 2019, http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/2019-human-development-index-ranking.

[5] Karl Blanchet, Feroz Ferozuddin, Ahmad Jan J. Naeem, Farhad Farewar, Sayed Ataullah Saeedzai and Stephanie Simmonds, “Priority setting in a context of insecurity, epidemiological transition and low financial risk protection, Afghanistan,” World Health Organization Bulletin 97 (1 April 2019): 347–376, https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/97/5/18-218941/en/.

[6] National Health Strategy 2016‒2020: Sustaining Progress and Building for Tomorrow and Beyond, Ministry of Public Health, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, September 2016, 9, http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/afghanistan/afghanistan_mophstrategy2016-2020_final09september2016111201614508950553325325.pdf.

[7] For more information on India’s aid to Afghanistan, see “India – Afghanistan Relations,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, August 2012, https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/afghanistan-aug-2012.pdf. Also see “India-Afghanistan Relations,” Embassy of India, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2015, https://eoi.gov.in/kabul/?0354?000.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Indian Companies Invest In Afghanistan’s Healthcare,” Tolo News, 17 March 2019, https://tolonews.com/business/indian-companies-invest-afghanistan%E2%80%99s-healthcare

[10] Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan between the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, which is not recognized by the United States as a state and is known as the Taliban and the United States of America, 29 February 2020, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Agreement-For-Bringing-Peace-to-Afghanistan-02.29.20.pdf.

[11] Seth G. Jones, Lee H. Hilborne, C. Ross Anthony, Lois M. Davis, Federico Girosi, Cheryl Benard, Rachel M. Swanger, Anita Datar Garten and Anga Timilsina, Securing Health: Lessons from Nation-Building Missions, RAND Corporation, 2006, 189, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.7249/mg321rc.15.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A311f8038b07b81abeea084dce6b7dd55.

[12] Zachary Laub, “The Taliban in Afghanistan,” Council on Foreign Relations, 4 July 2014, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/taliban-afghanistan.

[13] For more details on the history of war in Afghanistan, see “Afghanistan profile – Timeline,” BBC News, 9 September 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-south-asia-12024253.

[14] Lesley Strong, Abdul Wali and Egbert Sondorp, “Health Policy in Afghanistan: two years of rapid change,” London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2005, 9, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e081/f95d61ae0ebf75d5dd145c728520cc731d71.pdf.

[15] For more details on “Deobandism,” see Ahmed Rashid, Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia [Second Edition] (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010), 88. For more details on Wahabism and Salafism, see Sayed Hassan Akhlaq, “Taliban and Salafism: a historical and theological exploration,” Open Democracy, 1 December 2013, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/taliban-and-salafism-historical-and-theological-exploration/.

[16] A. Faiz, “Healthcare under the Taliban,” The Lancet, 1997, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9130961.

[17] Stephanie Dubitsky, “The Health Care Crisis Facing Women Under Taliban Rule in Afghanistan,” Human Rights Brief 6, no. 2, article 7 (1999): 1, https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1576&context=hrbrief.

[18] Ali M. Latifi, “Years of war and poverty take toll on Afghanistan’s healthcare,” Aljazeera, 25 May 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/05/years-war-poverty-toll-afghanistan-healthcare-190525101842119.html.

[19] “Afghanistan’s Health Crisis,” POV, 9 September 2002, http://archive.pov.org/afghanistanyear1380/afghanistans-health-crisis/.

[20] Ibid.

[21] A. Faiz, op. cit.

[22] “Taliban,” Encyclopædia Britannica, 11 December 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Taliban.

[23] Seth G. Jones, Lee H. Hilborne, C. Ross Anthony, Lois M. Davis, Federico Girosi, Cheryl Benard, Rachel M. Swanger, Anita Datar Garten and Anga Timilsina, op. cit.

[24] For more information on the role of NGOs in healthcare during the Taliban era of Afghanistan, see “Afghanistan: Civilians at Risk,” A panel discussion co-sponsored by Medicines Sans Frontieres and the 92nd St. Y, 20 October 2001, https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/what-we-do/news-stories/research/afghanistan-civilians-risk.

[25] John R. Acerra, Kara Iskyan, Zubair A. Qureshi and Rahul K. Sharma, “Rebuilding the health care system in Afghanistan: an overview of primary care and emergency services,” International Journal of Emergency Medicine 2, no. 2 (June 2009), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2700223/.

[26] The World Health Report 2000, World Health Organization, 2000, 202–203, https://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/whr00_en.pdf?ua=1.

[27] Ibid., 150.

[28] “Country Profile: Afghanistan,” Library of Congress, Federal Research Division, August 2008, https://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/cs/profiles/Afghanistan.pdf.

[29] Prabhu Chawla, “IC 814 hijack: Tough negotiation begins as India is up against desperate terrorists and Talibans,” India Today, 10 January 2000, https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/cover-story/story/20000110-ic-814-hijack-tough-negotiation-begins-as-india-is-up-against-desperate-terrorists-and-talibans-776909-2000-01-10.

[30] “Outcry as Buddhas are destroyed,” BBC News, 12 March 2001, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/1216110.stm.

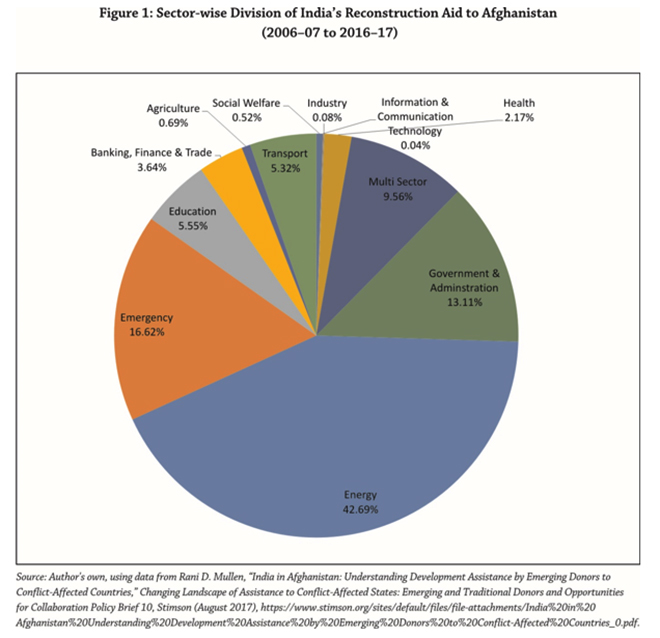

[31] Rani D. Mulle, “India in Afghanistan: Understanding Development Assistance by Emerging Donors to Conflict-Affected Countries” in Changing Landscape of Assistance to Conflict-Affected States: Emerging and Traditional Donors and Opportunities for Collaboration, ed. Agnieszka Paczynska, Policy Brief 10, Stimson, August 2017, https://www.stimson.org/sites/default/files/file-attachments/India%20in%20Afghanistan%20Understanding%20Development%20Assistance%20by%20Emerging%20Donors%20to%20Conflict-Affected%20Countries_0.pdf.

[32] Partha Pratim Basu, “India and Post-Taliban Afghanistan: Stakes, Opportunities and Challenges,” India Quarterly: A Journal of International Affairs63, no.3 (1 July 2007): 91–92, https://doi.org/10.1177/097492840706300304.

[33] Shanthie Mariet D’Souza, “India’s Aid to Afghanistan: Challenges and Prospects,” Strategic Analysis, 10 December 2007, 834, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09700160701662328.

[34] Agreement on Cooperation in the Field of Health Care and Medical Sciences between the Republic of India and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, Embassy of India in Kabul, Afghanistan, 2005, https://eoi.gov.in/kabul/?pdf0643?000.

[35] Partha Pratim Basu, op. cit., 92–93.

[36] Shakti Sinha, “Rising Power and Peacebuilding: India’s role in Afghanistan,” in Rising Power and Peacebuilding: Breaking the Mold?, eds. Charles T. Call and Cedric de Coning (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 140, https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Rising+Power+and+peace+building%3A+India%27s+role+in+AFGHANISTAN&btnG=.

[37] India and Afghanistan: A Development Partnership, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 8, https://mea.gov.in/Uploads/PublicationDocs/176_india-and-afghanistan-a-development-partnership.pdf.

[38] Ibid., 14.

[39] Jisha Krishnan, “India and China bridging the healthcare gap in Afghanistan,” Health Analytics Asia, 2 August 2019, https://www.ha-asia.com/how-are-india-and-china-bridging-the-healthcare-gap-in-afghanistan/.

[40] India and Afghanistan: A Development Partnership, op. cit., 14.

[41] Neelapu Shanti, “Development cooperation marks Afghan-India partnership,” The Economic Times, 3 September 2018, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/blogs/et-commentary/development-coop-marks-afghan-india-partnership/.

[42] “India-Afghanistan Relations,” op. cit.

[43] India and Afghanistan: A Development Partnership, op. cit., 28–29.

[44] Nandita Palrecha and Monish Tourangbam, “India’s Development Aid to Afghanistan: Does Afghanistan Need What India Gives?” The Diplomat, 24 November 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/11/indias-development-aid-to-afghanistan-does-afghanistan-need-what-india-gives/.

[45] Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury, “India signs 11 MoUs worth 9.5 million with Afghanistan,” The Economic Times, 21 January 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/india-signs-11-mous-worth-9-5-million-with-afghanistan/articleshow/67617756.cms?from=mdr.

[46] India and Afghanistan: A Development Partnership, op. cit., 14.

[47] Jisha Krishnan, op. cit.

[48] “India-Afghanistan Relations,” op. cit.

[49] Shadi Khan Saif, “Afghan ministry takes step against counterfeit medicine,” AA, 29 0ctober 2017, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/afghan-ministry-takes-step-against-counterfeit-medicine/951043.

[50] “India-Afghanistan Relations,” op. cit.

[51] Krzysztof Iwanek, “36 Things India Has Done for Afghanistan,” The Diplomat, 8 January 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/01/36-things-india-has-done-for-afghanistan/.

[52] Shakti Sinha, op. cit.

[53] Afghans First: India at Work in Afghanistan, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 1, http://www.mea.gov.in/Uploads/PublicationDocs/189_Afghanistan-First.pdf.

[54] Shanthie Mariet D’Souza, op. cit., 834.

[55] “India-Afghanistan Relations,” op. cit.

[56] Neelapu Shanti, op. cit.

[57] Krzysztof Iwanek, op. cit.

[58] Waslat Hasrat-Nazimi, “Afghans turn to India’s hospitals for treatment,” DW, 29 November 2013, https://www.dw.com/en/afghans-turn-to-indias-hospitals-for-treatment/a-17260216.

[59] “India further liberalises visa policy for Afghan nationals,” The Economic Times, 3 February 2017, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/india-further-liberalises-visa-policy-for-afghan-nationals/articleshow/56959978.cms?from=mdr.

[60] “India-Afghanistan Relations,” op. cit.

[61] Bhairvi Tandon, “India’s soft power advantage in the great game of Afghanistan,” Expert Speak, Observer Research Foundation, 1 July 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/indias-soft-power-advantage-in-the-great-game-of-afghanistan-52624/.

[62] Shakti Sinha, op. cit.

[63] “India a Hub for Patients From Afghanistan,” Refugees in the Media, 1 November 2013, https://www.unhcr.org.in/index.php?option=com_news&view=detail&id=30&Itemid=117.

[64] Joe Harkins, “Afghan Medical Tourism Patients Find Welcome Mats in India,” Medical Tourism Magazine, 2014, https://www.medicaltourismmag.com/article/afghan-medical-tourism-patients-find-welcome-mats-india.

[65] “Indian Companies Invest In Afghanistan’s Healthcare,” Tolo News, 17 March 2019, https://tolonews.com/business/indian-companies-invest-afghanistan%E2%80%99s-healthcare.

[66] Ajay Shukla, “India Does Not Need Boots on Afghan Ground,” The New York Times, 22 September 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/22/opinion/india-afghanistan-pakistan.html.

[67] Nandita Palrecha and Monish Tourangbam, op. cit.

[68] “How has Afghanistan achieved better health for its citizens?” World Bank Afghanistan, 5 April 2018, https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/how-has-afghanistan-achieved-better-health-its-citizens.

[69] “Afghanistan Builds Capacity to Meet Healthcare Challenges,” World Bank, 22 December 2015, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2015/12/22/afghanistan-builds-capacity-meet-healthcare-challenges.

[70] “How has Afghanistan achieved better health for its citizens?” World Bank Blogs, 5 April 2018, https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/how-has-afghanistan-achieved-better-health-its-citizens.

[71] “Obstructing health services,” Afghanistan Times, 18 July 2019, http://www.afghanistantimes.af/editorial-obstructing-health-services/.

[72] “Afghanistan hospital attack death toll soars to 39,” Aljazeera, 20 September 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/09/killed-car-bomb-attack-afghan-province-zabul-190919042138106.html.

[73] Sharifullah Sharfat and Ron Synovitz “Taliban Targets Medical Clinics In New Afghan Insurgency Strategy,” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, 27 September 2017, https://www.rferl.org/a/afghanistan-taliban-targets-hospitals-strategy/28760791.html.

[74] Partha Pratim Basu, op. cit., 109.

[75] Shanthie D’Souza, “India, Afghanistan and the ‘End Game’?” ISAS Working Paper No. 124, National University of Singapore, 23 September 2012, 12 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2150711.

[76] Ashley Jackson, “Life under the Taliban shadow government,” Report (Overseas Development Institute), June 2018, 10, https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12269.pdf.

[77] Rahimullah Yusufzai, “The Taliban And India Can Be Reconciled: Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid spoke to Rahimullah Yusufzai,” Interview, Outlook, 5 April 2010, https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/the-taliban-and-india-can-be-reconciled/264839.

[78] Harsh V. Pant, “India’s dilemmas in Afghanistan,” Expert Speak, Observer Research Foundation, 2 August 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/research/indias-dilemmas-in-afghanistan-53378/.

[79] Kallol Bhattacharjee, “Taliban hints at possible dialogue with India,” The Hindu, 26 August 2019, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/taliban-hints-at-possible-dialogue-with-india/article29279015.ece.

[80] “US-Taliban deal: Can peace finally come to Afghanistan?” Aljazeera, 7 March 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/talktojazeera/2020/03/taliban-deal-peace-finally-afghanistan-200306070535568.html.

[81] Afghanistan: Background and U.S., Policy In Brief, Congressional Research Service, 11 March 2020, Summary, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45122.pdf.

[82] Pamela Constable, “Standoff between Afghan President Ghani and rival Abdullah threatens Taliban peace deal,” The Washington Post, 15 March 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/standoff-between-afghan-president-ghani-and-rival-abdullah-threatens-peace-deal/2020/03/15/41d4e8e8-6657-11ea-8a8e-5c5336b32760_story.html.

[83] Dawood Azami, “Afghanistan war: What could peace look like”? BBC World Service, 14 July 2019.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV