-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

While India-China competition and Chinese assertiveness have triggered some changes in Bhutan’s foreign policy, recent developments suggest that continuity still looms large in Bhutan-India relations

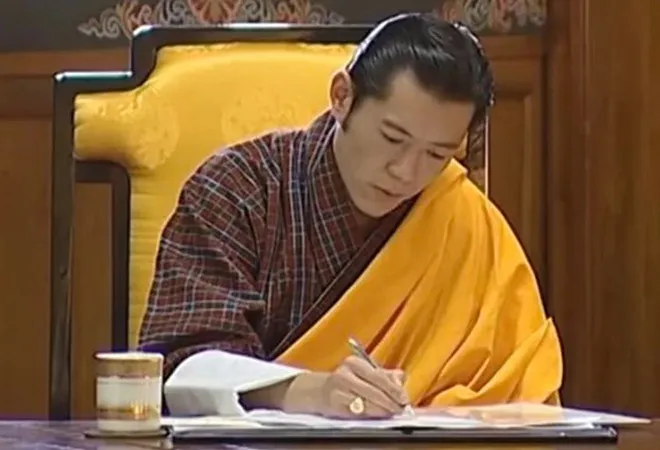

Earlier this month, Bhutan’s king Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuk was on a three-day visit to India. The visit closely followed prime minister Lotay Tshering’s comments on Bhutan’s border disputes with China. The comments had garnered a lot of attention, as Indian media projected Bhutan to be “moving away from New Delhi.” Two aspects seem to have largely triggered this reaction: one, the denial of Chinese intrusions and infrastructure installations within Bhutanese territories and second, expressing that China is as much of a stakeholder as India and Bhutan are in the Doklam issue.

While India-China competition and Chinese assertiveness have triggered some changes in Bhutan’s foreign policy, recent developments suggest that continuity still looms large in Bhutan-India relations.

China disputes the following territories with Bhutan: in the north, Pasamlung and Jakarlung valleys, both of which are culturally vital for Thimphu and in the west, Doklam, Dramana, and Shakhatoe, Yak Chu and Charithang Chu, and Sinchulungpa and Langmarpo valleys. The Doklam trijunction is crucial for India as it lies precariously close to the Siliguri Corridor. Recently, China has also claimed the Sakteng sanctuary, which is on Bhutan’s east and does not border China.

Starting in 1984, Bhutan and China started bilateral negotiations on their territorial disputes. To date, they have had 24 rounds of negotiations and 11 rounds of Expert Group Meetings (EGM).

Following the stalemate in negotiations in 1998, Bhutan suggested an expert technical group that will draw the boundaries by studying maps. By 2015, China and Bhutan had finished surveying the technical field survey reports of the Central and Western disputed sectors.

Despite these engagements and efforts, Chinese intrusions in Bhutanese territories occurred on regular occasions. China had encouraged its citizens to settle in the disputed areas and built roads, infrastructure, and permanent settlements within Bhutanese territories.

With no progress in negotiations and tensions with India skyrocketing after the Galwan clashes, Beijing grew more assertive.

A similar intrusion in the Doklam trijunction in 2017, triggered a standoff between India and China. Simmering tensions between the two Asian giants also compelled Bhutan to put on hold its 25th round of negotiations with China.

A year later, the Chinese vice foreign minister visited Bhutan intending to resume the stalled border negotiations. With no progress in negotiations and tensions with India skyrocketing after the Galwan clashes, Beijing grew more assertive. In July 2020, China made new claims in Bhutan’s east—in the Sakteng wildlife sanctuary. Between 2020-2021, several satellite images indicated that China is building new villages in Bhutan.

With its survival at stake, Bhutan low-key resumed negotiations with China. In April 2021, both countries held the 10th EGM and finalised an MoU on a three-step roadmap for expediting the boundary negotiations that was signed in October 2021. In October 2022, Sun Weidong, the Chinese ambassador to India, visited Bhutan to expedite the negotiations. The 11th round of EGM took place in January 2023, where both the players agreed to push forward the three-step roadmap and to hold the 25th round of negotiations. A Chinese technical team is expected to arrive in Bhutan in the coming months.

After nearly 40 years of negotiations, there is some optimism within Bhutan for demarcating its borders with China, barring the Doklam trijunction.

For Bhutan, this seems like an opportunity to end the dispute once and for all before India-China relations worsen even further.

Essentially, Bhutan has been calculative and accommodative of Chinese sensitivities and interests. Its denial of Chinese intrusions and infrastructure further indicates that it may be contemplating ceding certain territories in its Northern and Western disputed sectors if that might lead to a broader settlement.

PM Tshering’s comments on China being an equal stakeholder in Doklam reflects India’s stance during the standoff, where New Delhi urged Beijing to have a tripartite engagement in the trijunction region.

That said, none of these developments on border negotiations would have occurred without some awareness in India about them. In 2020, India reportedly asked Thimphu to end its border disputes with China so that all the stakeholders could focus on the complex trijunction.

PM Tshering’s comments on China being an equal stakeholder in Doklam reflects India’s stance during the standoff, where New Delhi urged Beijing to have a tripartite engagement in the trijunction region. Even during the king’s recent visit, India provided a standby credit facility and offered financial assurances to Bhutan for its 13th Five Year Plan and administrative reforms. Thus, indicating continuity and understanding between both nations.

However, this current episode underscores a broader trend in South Asia, where India-China competition is increasingly the primary determinant of the foreign policy of South Asian countries. Despite the Bhutan-India relationship largely being defined by continuity, Beijing is using its intimidation tactics to set the agenda for the region and threaten India’s security and status.

At a time when trust for China in India has plummeted to a historic low and even as the Doklam issue remains unresolved, the India-Bhutan-China triangle is set to undergo another stress test.

This commentary originally appeared in Financial Express.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Aditya Gowdara Shivamurthy is an Associate Fellow with the Strategic Studies Programme’s Neighbourhood Studies Initiative. He focuses on strategic and security-related developments in the South Asian ...

Read More +

Professor Harsh V. Pant is Vice President – Studies and Foreign Policy at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. He is a Professor of International Relations ...

Read More +