Background

India-US defence cooperation began during the 1962 Sino-Indian War, when the US supplied India with transport aircraft, weapons, and training. The two sides and the UK also conducted air exercises for a limited period. The US offered India about US$500 million in credit and grants for five years to purchase non-combat military equipment, but this never took off and ended when the US froze military ties with India and Pakistan in the wake of the 1965 war.

Current collaboration has its roots in the memorandum drafted by Lt. Gen. Claude Kicklighter in the 1990s. Lt. Gen. Kicklighter was the commander of the army component of the US Pacific Command (now the Indo-Pacific Command) headquartered in Hawaii. It is through this command that all subsequent Indo-US military cooperation has been channelled. At the time, aware of India’s dependence on Russian military equipment, which was much cheaper than those available in the US and Europe, the US promoted the idea of collaborating in defence technology. It may be noted that Lt. Gen. Kicklighter’s proposals were made possible by a thaw in Indo-US relations during the Reagan Administration and driven by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her successor Rajiv Gandhi over the 1982-89 period.

The Indo-US Memorandum of Understanding on Technology Transfer was signed in December 1984 after India assured that the US technology obtained would not be used for nuclear proliferation or missile production. The arrangement was based on the loosening of US export control restraints. One of the projects identified for the purpose was the light combat aircraft (LCA), now known as Tejas, for which the US agreed to supply the General Electric F404 engine and assist in developing several sub-assemblies.

Post-Cold War geopolitical developments were not easy for India, whose good friend, the Soviet Union, had come apart. It confronted American suspicion, manifested by the Pentagon’s Defence Policy Guidance 1994-1999 document that spoke of India’s hegemonic aspirations in South Asia. In addition, there were pressures on the non-proliferation front and Kashmir. For its part, India sought to assuage fears of its Soviet connection by holding a series of exercises involving the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in the Andaman Seas and with the US off the west coast of India, now known as the Malabar Exercise.

There was a break in this trend in 1998 after India conducted its nuclear tests and the US imposed sanctions on India mandated by its Arms Export Control Act, including on the LCA collaboration. However, ties quickly normalised as a dialogue between US Deputy State Secretary State Strobe Talbott and Indian Foreign Minister Jaswant Singh, which began in 1999, worked to iron out differences between the two countries on strategic issues and non-proliferation. Subsequently, India got waivers on the sanctions at various points in time.

In 2000, Condoleezza Rice, the then US Secretary of State, wrote in Foreign Affairs: “India is an element in China’s calculation, and it should be in America’s too. India is not a great power yet, but it has the potential to emerge as one.”[1]

In 2001, when the US began its so-called global war on terror and attacked Afghanistan, the Indian Navy provided escort to US vessels transiting through the Malacca Strait. When the US started its operations in Iraq in March 2003, one of the countries that it approached to send troops there was India. The ruling BJP coalition’s number two, L.K. Advani, agreed to push the option during a visit to Washington, DC. But back home, Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee deftly outmanoeuvred him and turned down the suggestion.

Subsequently, in 2004, the US and India issued the ‘Next Steps in Strategic Partnership’,[2] which included negotiations to remove the export control regimes affecting India because it was not a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The US also agreed to collaborate with India on ballistic missile defence. This was when India-US security ties took a new turn, and the two countries announced a civil nuclear deal (in 2005), the eventual goal of which was strategic cooperation in all fields.[3]

Another portentous event during this period was the cooperation following the Indian Ocean tsunami in December 2004, which killed over 200,000 people. The Indian Navy was active in humanitarian relief and found like-minded navies of the US and its allies Australia and Japan as partners in the endeavour. The US and its allies noted the Indian Navy’s performance, and this partnership of countries—who all happened to be democracies—catalysed the idea of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad). [4]

Guiding Principles and Documents

The origin of the current relationship lies in the Indo-US Memorandum of Understanding on technology transfer signed in December 1984, followed by the visit of US Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger to New Delhi in 1986. This was the first visit by any US Defense Secretary to India, which led to the US providing the GE 404 engine for the LCA project.

This was followed by the ‘Kicklighter proposals’ of 1991, brought to New Delhi by Lt. Gen. Kicklighter. This envisaged US-India cooperation on land, sea, and air. The proposals focused on establishing consultative mechanisms, joint training, and strategic dialogue between the two militaries. In 1992, US Chief of Naval Operations Frank Kelso and Lt. Gen. Johnny Corns, Lt. Gen. Kicklighter’s successor, came to New Delhi for talks, and the two sides set up a military steering committee “to establish the basis for a long-term army-to-army relationship”.[5]

In 1992, India and the US held the inaugural Indo-US Malabar Exercise, the first time the two countries had worked together in a military exercise. Subsequently, India and the US participated in other exercises—the Yudh Abhyas in 2002, the Vajra Prahar (lightning strike; a Special Forces exercise held since 2010), and the Tiger Triumph (a tri-service exercise that began in 2019) and so on.

The ‘Agreed Minute on Defence Relations’ (1995) was the first document signed by the two defence ministries in the post-Cold War period.[a] This led to further cooperation in the defence sector and increased exchanges of personnel and information between the two militaries. Under this Minute, the two sides created the Defence Policy Group (DPG), headed by the US defence undersecretary and India’s defence secretary, to supervise bilateral defence ties. It also created a joint technical group, with the two groups holding their first meetings soon thereafter. The Minute became defunct following the US sanctions on India after the 1998 nuclear tests. The DPG process was only resumed after the Talbott-Singh dialogue in 2001. The 17th meeting of the group took place in May 2023 in Washington, DC, between India’s Defence Secretary Giridhar Aramane and the US Undersecretary for Defense Policy Colin Kahl.[6]

The US-India High Technology Cooperation Group (HTCG) was formed in November 2002 to provide a “standing framework” for issues relating to high technology between the two countries. It was co-chaired by the US Undersecretary for Industry and Security and the Indian Foreign Secretary. The idea was to steer strategic trade in controlled items and to create the environment for the development of such trade by shaping the legal and structural environment between the two countries. The HTCG helped US exports to India double from US$4 billion annually to US$8 billion between 2002-2005 and reduced the export license requirement by 25 percent.[7]

In January 2004, the two countries signed the ‘Next Steps in Strategic Partnership’, the most unambiguous indication that the India-US relationship was moving in a new direction. This involved cooperation in civilian nuclear activities, civilian space programmes, high-tech trade, and a dialogue on ballistic missile defence. Subsequent talks involved working out procedures to make India compliant with US rules and regulations.[8] The US announced the completion of the Next Steps in July 2005, enabling it to move on to the Indo-US nuclear agreement.[9]

The US also began to press India to sign the four foundational agreements it felt were necessary to meet the American legal requirements to promote India-US military cooperation. India agreed to the first, the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA), in 2002, a basic agreement aimed at ensuring the secrecy of communications between the two sides.[10]

However, it took 20 years or so for India to sign the other three—the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA) in 2016, an India-specific version of the Logistics Support Agreement (LSA) the US signs with other countries;[11] the Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA) in 2018, an India-specific version of the Communication and Information Security Memorandum of Agreement (CISMOA);[12] and the Basic Exchange Cooperation Agreement (BECA) in October 2020, which involves sharing of information in space and undersea domains.[13]

In June 2005, the two countries signed the 10-year ‘New Framework for the US-India Defense Relationship’. This agreement set a roadmap for their future defence cooperation, which also involved collaboration in multilateral operations, expanded two-way defence trade, and increased opportunities for technology transfer and cooperation relating to ballistic missile defence. An Indo-US Defence Joint Working Group was created, and its first meeting was held in April 2007.[14]

During Secretary of State Rice’s visit to New Delhi in March 2005, she told her Indian interlocutors that the Bush Administration wanted a “decisively broader strategic relationship.” As a senior US official accompanying her told the media, “its goal is to help India become a major world power in the 21st century,” adding that “we understand fully the implications, including the military implications of that statement.”[15]

A few months later, in July 2005, US President George W Bush and Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh announced agreement on an ‘Indo-US Civil Nuclear Deal’, through which the US removed important non-proliferation sanctions on India in exchange for India’s commitment not to conduct any more nuclear tests and place its civil nuclear facilities under International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards.[16] The deal was signed after all its conditions were fulfilled in 2008. More than civil nuclear trade, the agreement's goals were to clear the desk of the relationship cluttered by sanctions, upon which new strategic ties could be fashioned.

In June 2010, the ‘US-India Strategic Dialogue’ was launched to provide high-level guidance to the India-US relationship. The first meeting, held in Washington DC, was chaired by US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Indian External Affairs Minister S.M. Krishna. The dialogue set the stage for US President Barack Obama’s first visit to India in 2010. This was elevated to the ‘US-India Strategic and Commercial Dialogue’ following Obama’s visit to India as the chief guest at the 66th Republic Day celebrations in 2015.[17]

In addition, during Obama’s 2010 visit to Delhi, the waivers were extended, and India was provided with another set of exemptions on export controls and high-tech trade under the US Export Regulations and the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR).[18]

In 2012, the ‘Defence Trade and Technology Initiative’ (DTTI) was launched to encourage the co-production and co-development of military equipment. The aim was to ease bureaucratic hindrances from slowing down the process.[19]

India and the US made a ‘Joint Declaration on Defence Cooperation and Engagement’ in September 2013 to reinforce the 2005 ‘New Framework for Defence Relations’. It laid out their common security perspective and noted that the defence technology transfer, trade, research, co-development, and co-production relationship would be at the same level as their closest partners.[20]

The ‘Framework for the US-India Defense Relationship’ was renewed in 2015 during Obama’s visit to India. There was also agreement on four “pathfinder” projects under DTTI, as well as cooperation on aircraft carrier and jet engine technology. It was during this visit—the first time a US President was the chief guest on Republic Day—that India and the US signed the ‘Joint Strategic Vision for the Asia Pacific and Indian Ocean Region’.[21] The word “Indo-Pacific” had not yet entered the two countries’ strategic lexicon.

It was also during this visit that two government-to-government DTTI projects on mobile electric hybrid power sources and next-generation protective ensembles for chemical and bioweapons protections were signed.[22]

During Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the US in 2016, the US declared India a ‘Major Defense Partner’. This status is unique to India and signalled that the country would be treated at par with the US’s closest allies and partners.[23]

The ‘Indo-US Strategic Dialogue’ was replaced by the ‘2+2 dialogue’ involving joint meetings of their foreign and defence ministers in September 2018. The inaugural meeting was attended by US State Secretary Mike Pompeo and US Defense Secretary James Mattis, as well as their Indian counterparts, External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj and Defence Minister Nirmala Sitharaman. With this annual format, the supervision of defence issues is now at the ministerial level rather than with the DPG.[b],[24]

In August 2018, India was granted the designation of ‘Strategic Trade Authorisation Tier 1’ (STA-1) to enable US companies to export a greater range of dual-use and high-tech items to India. This status is available to NATO countries and close allies like South Korea, Australia, and Japan.[25] The aim was also to link up to the Indian government’s plans under the Innovations for Defence Excellence (iDEX) framework established in 2018 to foster innovation and technology development in the defence and aerospace sector.[26]

India also received a waiver for the draconian US Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAASTA) through an amendment in the National Defense Authorisation Act of 2019. The waiver ensured India was not punished for importing Russian weapons like the S-400 long-range surface-to-air missile system. [27]

In 2019, India and the US signed the Industrial Security Agreement (ISA) at their second ‘2+2 dialogue’ in Washington, DC. The agreement aimed to deepen collaboration between the US and Indian defence industries by enabling the exchange of classified military information.[28]

At the third ‘2+2’ meeting in October 2020, which took place in the wake of the Chinese coercive actions in India’s eastern Ladakh border, India signed the BECA for geospatial cooperation and also positioned an Indian liaison officer at NAVCENT, the US Central Command’s naval headquarters in Bahrain. At the same time, a US Navy officer was deputed for the Information Fusion Center—Indian Ocean Region in Gurugram, India. The two sides also decided to enhance their maritime information sharing and domain awareness.[29]

Following the ASEAN Summits in Manila in 2017, attended by their respective leaders, India, the US, Australia, and Japan agreed to revive the Quad to counter China militarily and diplomatically in the Indo-Pacific. In May 2018, the Pentagon renamed its Pacific Command (PACCOM) as its Indo-Pacific Command (INDO-PACCOM). Within the Pacific framework, China loomed large, but by expanding it to include the Indian Ocean and India, it looked a bit smaller. It was a subliminal message to and on China. [30]

In January 2021, just before leaving office, the Trump Administration declassified its ‘Indo-Pacific Strategy', which declared that one of the “top interests” of the US was to “maintain U.S. primacy in the region”. To this end, it wanted to create a situation where “India remains pre-eminent in South Asia and takes the leading role in maintaining Indian Ocean security, increases engagement with southeast Asia, and expands its economic, and diplomatic cooperation with other U.S. allies and partners in the region.” The actions it needed to take was to assist India to “build a stronger foundation for defense cooperation and interoperability.” In addition, the US sought to partner India on the areas of cyber and space security and maritime domain awareness and “expand US-India intelligence sharing and analytic exchanges.”[31]

In September 2021, at an ISA summit, the two sides agreed to establish an ‘Indo-US Industrial Security Joint Working Group’ to align the policies and procedures to enable defence industries to collaborate on cutting-edge technologies. [32]

The US, the UK, and Australia revealed a trilateral military alliance called AUKUS in September 2021. While the alliance focuses on providing nuclear-propelled submarines for Australia, it also deals with cooperation in cyber issues, AI, quantum technologies, undersea capabilities, electronic warfare, and hypersonic capabilities.[33] From India’s point of view, this was a critical separation point from the Quad grouping. It is clear now that defence mechanisms are not part of the Quad, as indicated by the joint statement issued after the second in-person meeting of its leaders in Tokyo in May 2022.[34]

At the April 2022 ‘2+2’ meeting, India announced that it had joined the US-led Bahrain-based Combined Maritime Task Force (CTF) as an associate partner. In November 2023, it became a full-fledged member. The CTF has 41 members and specialises in counter-narcotics, counter-smuggling, and counter-piracy, which it deals with through four joint task forces.[c] In addition, the two sides concluded a Space Situational Awareness Agreement and commenced dialogues on defence space and AI.[35]

Table 1: Important India-US Defence Initiatives

| Year |

Name of Agreement |

| 1991 |

Steering committee “to establish the basis for a long-term army-to-army relationship.” |

| 1992 |

Indo-US Malabar Exercise |

| 1995 |

Minute on Defence Relations - Defence Policy Group (DPG) |

| 2002 |

General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) |

| 2004 |

Next Step in Strategic Partnership (NSSP). |

| 2005 |

New Framework for the US-India Defense Relationship |

| 2012 |

Defence Trade and Technology Initiative (DTTI) |

| 2015 |

Joint Strategic Vision for the Asia Pacific and Indian Ocean Region. |

| 2016 |

The US declared India as a Major Defense Partner (MDP) |

| 2016 |

Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA) |

| 2018 |

The Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA) |

| 2018 |

India was granted the designation of Strategic Trade Authorisation Tier 1 (STA-1) |

| 2018 |

Beginning of “2+2” Dialogue |

| 2019 |

Industrial Security Agreement (ISA) |

| 2020 |

Basic Exchange Cooperation Agreement (BECA) |

| 2021 |

Indo-US Industrial Security Joint Working Group |

| 2022 |

India announced that it had become an associate partner in the US-led, Bahrain-based Combined Maritime Task Force (CMF). |

Source: Compiled from various sources

Military Exercises

Bilateral exercises

- Vajra Prahar: In 2003, the two sides held an early version of a special forces exercise called Vajra Prahar at the Indian Army’s counterinsurgency and jungle warfare school in Vairengte, Mizoram. This was more of a training exercise, and subsequently, hundreds of US military personnel regularly participated in the training courses there. The main Vajra Prahar Special Forces exercise was held in 2010, a platoon-level (30-50 soldiers) exercise. The 13th edition of the exercise was held in August 2022 at Bakloh (Himachal Pradesh) at the Special Forces Training School.[36]

- Yudh Abhyas: The first army exercise called Yudh Abhyas (war rehearsal) was initiated in 2004 and held at the Mahajan field firing range close to the Pakistan border in Rajasthan. The exercise was held at the battalion level with roughly 250 troops from each side, with brigade-level mission planning. The exercise involved combat basics like patrolling, ambushes, and close-quarter combat. The 18th edition of the exercise was held in November 2022 at the Auli High Altitude Warfare Training Camp in Uttarakhand. The focus was joint operations in high-altitude terrain. It involved 350 troops from each country. Since the Indian version of the exercise was usually held at the Mahajan field firing range, the decision to have it at Auli, close to the India-China border, was significant.[37]

- Cope India: The two air forces held exercises called Cope India starting in 2004. The first exercise was held at the Air Force Station in Gwalior, where the Indian Air Force bases its Mirage 2000 fighters. The exercise was not held between 2010 and 2018. Cope India 2023 was an extensive exercise held at the air force stations in Kalaikunda, Panagarh, and Agra, which involved frontline Indian and US aircraft and featured the US B1B strategic bomber. Japanese Self-Defence Forces personnel participated as observers.[38]

- Tiger Triumph: In 2019, the Indian and American militaries held their first tri-service exercise in the Bay of Bengal area, called the TriServices India U.S. Amphibious Exercise (Tiger Triumph). The focus was on enhancing interoperability and small-unit skills relating to humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. Over 500 US marines and sailors and 1200 Indian personnel participated in the nine-day exercise. Both sides fielded one ship each, the USS Germantown and the INS Jalashwa (ex-USS Trenton).[39] The second edition of the exercise was conducted in October 2022, also at Vishakhapatnam.[40] However, this was smaller in scale, with just 50 combined participants, and focused on staff planning and processes for diplomatic, operational and logistical coordination.

- There have been other bilateral exercises, including the Tarkash joint ground force counterterrorism exercise between the US Special Forces and India’s National Security Guard, and Sangam, a naval special forces exercise involving India’s Marine Commandos with the US Navy SEALs.

Multilateral Exercises

- Malabar: After the collapse of the Soviet Union, India reached out to the US through the Malabar Exercise with the US Navy, which began in the 1990s, but these were passage exercises held off the Malabar coast in southern India. They were suspended in 1998 following India’s nuclear tests and US sanctions on the country. However, following the Talbott-Singh dialogue in 1999, the US and India found a middle ground in their relationship, and the exercises were resumed in 2002. By 2005, they increased in sophistication, involving war games with aircraft carriers and satellite communications. In 2014, Japan joined the exercise, and in 2020, Australia and they are now multilateral. Until 2006, the exercises were confined to the seas off India’s west (Malabar) coast, but subsequent exercises have occurred in the Philippines Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and the waters off Japan. The 26th edition of the exercise was held in November 2022 off the coast of Japan and involved 11 surface ships along with maritime patrol aircraft, helicopters, and submarines. A US nuclear-powered aircraft carrier participated, and India sent a stealth frigate, INS Shivalik, a corvette, and a P8I maritime reconnaissance and ASW aircraft.[41] The 27th edition of the exercise was hosted by Australia for the first time in August 2023, though at a slightly lower scale. Two Indian Navy ships—the INS Sahyadri, a stealth frigate, and the INS Kolkata, a destroyer—participated, along with ships and aircraft from Japan, the US, and Australia.[42]

- RIMPAC: India has participated in the US-led Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC) since 2012, with its frigate INS Sahyadri participating in 2014. In 2022, the frigate Satpura participated along with the Indian Navy’s P8I aircraft. The exercise involves advanced anti-submarine warfare operations and is said to be the world’s largest naval exercise.[43]

- Milan: The Milan (friendship) multilateral exercise began in 1995 as a post-Cold War confidence-building measure with ASEAN. The exercise was initially held in the Andaman Sea but given its increased size and scale, it is now hosted at the Vishakhapatnam port. The US first participated in the 2022 edition, which was the largest ever, by sending a destroyer and a maritime patrol aircraft. The 2022 exercise involved 42 nations, 26 warships, 21 aircraft, and a submarine.[44] In February 2024, India hosted the latest iteration of the mega exercise with over 50 foreign navies, 15 warships, and a maritime patrol aircraft. About 20 Indian Navy ships and two aircraft carriers and the P8I maritime patrol aircraft also participated. [45]

- Cutlass Express: This navy exercise is sponsored by the US Africa Command. In 2019, an Indian Navy frigate participated in the exercises near Djibouti. The 2023 edition was launched in Seychelles, took place in Djibouti, Kenya, and Mauritius, and included an Indian Navy frigate, INS Trikand. The 2023 exercise took place in a combined format with the international maritime exercise hosted by the US Central Command. The combined exercise featured 7,000 military personnel, 35 ships, and 30 uncrewed and AI systems from 50 countries.[46]

- Le Perouse: This navy exercise is sponsored by France and held in the Indian Ocean Region. Its third edition brought together elements of seven navies—the Quad countries plus France, the UK, and Canada—for a two-day exercise in March 2023. An Indian Navy stealth frigate INS Sahyadri, fleet tanker INS Jyoti, and a P8I maritime reconnaissance aircraft participated in what was billed as “high level” exercises that included air defence.[47]

- Sea Dragon: The US-led anti-submarine warfare naval exercise held its fifth edition near Guam in March 2023, and included forces from the Quad countries, plus Canada and South Korea. An Indian P8I maritime patrol and ASW aircraft participated. This was India’s third year of participation.[48]

- Pitch Black: An air force exercise hosted by Australia, held every two years. Its last iteration was in 2022, with forces from 17 countries participating, including an Indian contingent of four SU-30MKI fighters and two C-17 transport aircraft. The exercise hosted up to 2500 participants and 100 aircraft worldwide. The exercise features a range of realistic, simulated threats in both day and night operations.[49]

- Red Flag: This is a major US Air Force aerial combat exercise, with units from allied and partner countries participating. It is held several times each year in the US. Indian combat aircraft and tankers joined in 2008 and 2016. In 2016, four IAF Su-30MKI, four Jaguar fighters, two C-17 transport jets, and two mid-air refuelling aircraft formed the Indian contingent at the exercise. In 2020, the Indian Air Force was poised to participate, but plans were cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. India has not participated in Red Flag since then.[50]

Table 2: India-US Multilateral Exercises

| Year of Commencement |

Name of Exercise |

Services Involved |

| 1992 |

Malabar Exercise (Eventually became Multilateral) |

Navy |

| 1995 |

Milan (US Joined in 2022) |

Navy |

| 2008 |

Red Flag |

Air Force |

| 2012 |

RIMPAC |

Navy |

| 2014 |

Sea Dragon |

Navy |

| 2008 |

Red Flag |

Air Force |

| 2019 |

Cutlass Express |

Tri Service |

| 2022 |

Pitch Black |

Air Force |

| 2023 |

La Perouse (France Initiative) |

Navy |

Source: Compiled from various sources

India’s Defence Acquisitions from the US

In 2007, India began its purchases of US defence equipment modestly by acquiring the USS Trenton (renamed Jalashwa), an amphibious transport dock, along with six Sikorsky S-61 Seaking helicopters and six C 130J transport aircraft for use during special operations.[51] In 2011, India indicated it would buy another six C-130J aircraft, which would be based in Panagarh (West Bengal), the headquarters of the Mountain Strike Corps. The sale was eventually concluded in 2013.[52]

In 2008, India purchased 20 AGM-84L Harpoon Block II missiles to be used by its maritime strike Jaguar aircraft, Boeing P8I maritime reconnaissance, and ASW aircraft.[53] Subsequently, in 2014, it acquired another 12 Harpoon missiles to equip its refurbished Sishumar (Type 209) submarines.[54] In 2020, India acquired another 10 air-launched Harpoon missiles to be used with the P8I aircraft.[55]

In 2009, India signed on to a much bigger deal when it decided to acquire eight P 8I long-range maritime reconnaissance and ASW aircraft from the US for US$2.1 billion. This was a direct commercial transaction with Boeing, the aircraft manufacturer.[56] Subsequently, India acquired four more P8Is in 2016 and ordered another six aircraft through the Foreign Military Sales process in 2021.[57] In 2020, it also acquired 16 lightweight torpedoes that can be launched from the P8I.[58]

In 2010, India decided to purchase 10 Boeing C 17 Globemaster II transport aircraft along with some related equipment for US$5.8 billion. This was aimed at enhancing the Indian Air Force’s heavy airlift capability.[59] It purchased another aircraft in 2017.[60]

Also in 2010, India decided to purchase next-generation attack helicopters. The US Defense Department made an advance notification of the possible sale of 22 AH-64D Apache attack helicopters in a package worth US$1.4 billion for the Indian Air Force. However, the deal only culminated in 2015. Subsequently, India also ordered six more Apaches for its army.[61]

India made a significant purchase of 145 M 777 lightweight howitzers and associated equipment worth US$885 million in August 2013 to enhance its military capability in the mountain areas.[62]

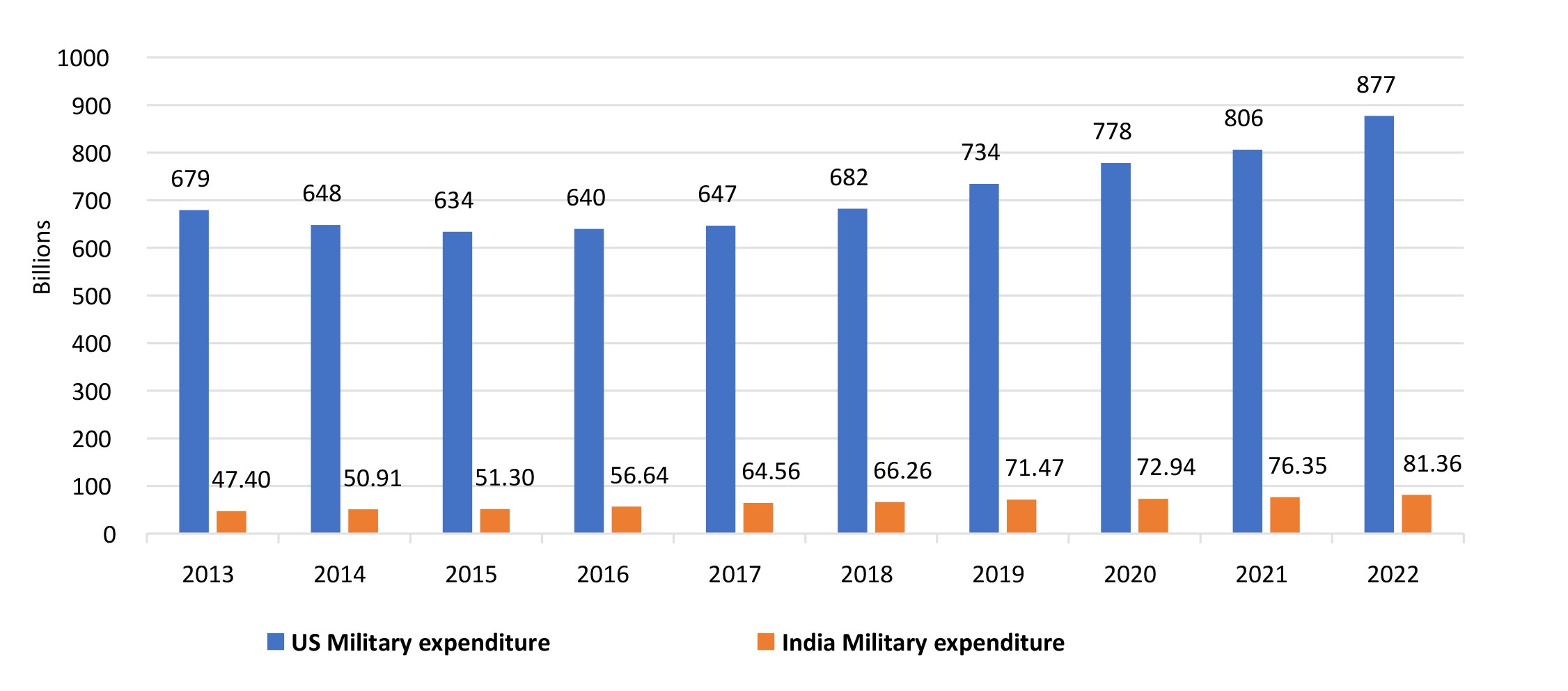

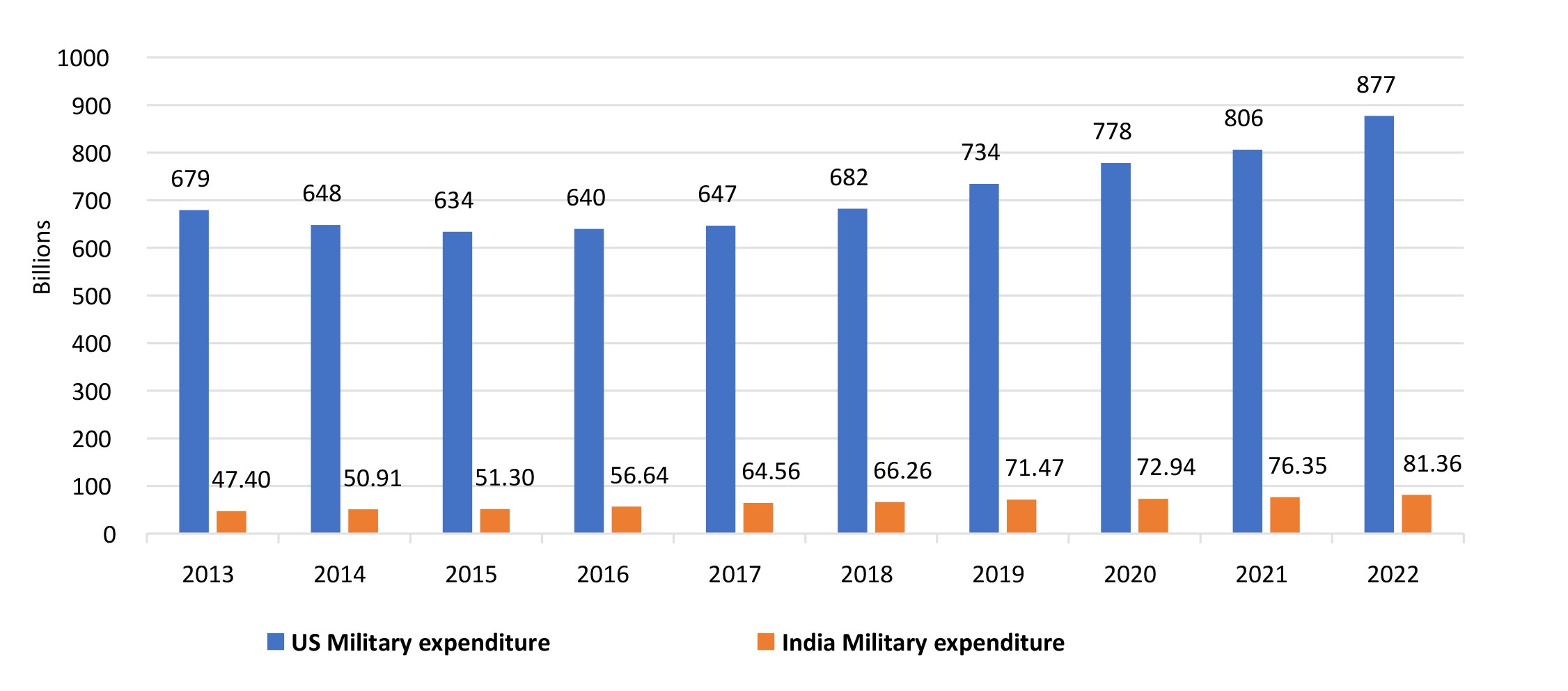

Figure 1: Value of India-US Defence Ties (2013-2022; in US$)

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

In 2019, India decided to buy 24 MH-60R multi-mission helicopters with associated multi-mode radars, radio equipment, engines, targeting systems, and Hellfire missiles at a cost of US$2.6 billion.[63]

In 2020, India requested, and the US approved, the purchase of an Integrated Air Defense Weapon System comprising five AN/MPQ-64FI Sentinel radar systems, 118 AMRAAM AIM 120C missiles, and 134 Stinger missiles. The deal was worth US$1.867 billion and is likely to provide close-in air defence for the national capital.[64]

While India initially decided to purchase MQ9A Sea Guardian drones from the US, it leased two drones in November 2020. In 2020, US equipment like Boeing P 8I Poseidon and Sea Guardian drones were also used for intelligence gathering along the line of actual control with China.[65]

In October 2021, the Indian and US defence departments agreed to sign a project agreement to collaborate on developing an air-launched unmanned aerial vehicle as part of the DTTI.[66]

Progress Since 2022

Although India-US defence cooperation grew substantially between 2000 and 2021, it did not involve any kind of a military alliance. India had purchased some US$20 billion worth of US defence equipment and weapons, but there had been little progress in the co-development and co-production of defence systems promised by the DTTI initiative.

However, in 2022-23, India-US defence ties have been marked by a qualitative shift. There are three factors for this. First are the tensions arising out of Chinese actions in eastern Ladakh in 2020; second is the increased friction between the US and China arising out of developments in the Indo-Pacific; and third is the US decision to create a new domestic industrial framework emphasising semiconductors, green energy, and nearshoring and friendshoring of its supply chains.

In May 2022, when Modi met US President Joe Biden in Tokyo, they announced an ‘Initiative for Critical and Emerging Technologies’ (iCET). In January 2023, in preparation for Modi’s visit to Washington in June, Indian and American national security advisers met and gave shape to the iCET, and committed to launch it as an innovation bridge to link US and Indian defence startups. iCET was launched in Washington through an inaugural meeting during the Modi visit. The White House factsheet noted that the two countries were set to expand their “strategic technology partnership and defense industrial cooperation” not just between governments but also between businesses and academic institutions.[67]

In May 2023, India and the US held the inaugural ‘Advanced Domains Defense Dialogue’, which had been decided on during the ‘2+2 ministerial dialogue’ in 2022. This was at the sub-Cabinet officials level, and the two sides exchanged views on new defence domains emphasising space and artificial intelligence.[68] Parallel to this were discussions between US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin and his Indian counterpart Rajnath Singh on the issue of Indo-US defence industrial cooperation based on their ongoing activities arising from the 2013 ‘Joint Declaration on Defence Cooperation’ and the 2015 ‘Framework for the US-India Defence Relationship’. Under this, they issued a roadmap to assist the process till 2024, when the 2015 ‘Framework’ will be renewed. The US declared that it aims to make India “a logistic hub for the United States” in the Indo-Pacific. It also declared a commitment to integrate the Indian defence industry into the global supply chain of US defence and aerospace companies.[69]

Another key element was implemented in June 2023 with the launch of the ‘India-US Strategic Trade Dialogue’ in Washington DC. Foreign Secretary V.M Kwatra led the Indian delegation, whose objective was to facilitate the development and trade in “critical technology domains” such as semiconductors, space, telecom, quantum technology, AI, defence, and biotech. Steered in the US by Alan Estevez, the top US official dealing with export control and compliance at the US Department of Commerce’s powerful Bureau of Industry and Security, the dialogue aimed to ensure that the thicket of US regulations does not choke the process.[70]

Modi’s visit to the US in June 2023 was the culmination of the official-level processes that had begun in January of that year with the meeting of the two national security advisers in Washington, DC. Many of the defence deals announced were in the works for some time. The visit featured a welcome ceremony and state dinner, as well as an address to the US Congress. Deals related to US assistance in producing electric vehicles and pushing renewable energy projects were announced, as were some related to Micron Technology’s investment in a new chip plant in Gujarat. Overall, the visit led to positive outcomes for both sides.[71]

On 21 June 2023, during Modi’s visit, the Indian defence ministry and the US defense department launched a bilateral ‘Defence Acceleration Ecosystem’ (INDUS-X) to expand strategic technology and defence industrial cooperation, along the lines suggested by the two national security advisors in January, to establish an “innovation bridge” linking the US and India. India’s Innovations for Defence Excellence (iDEX) organisation and the office of the US Secretary of Defense will provide the Leadership for INDUS-X. This is envisaged as an ambitious venture that would connect industry and academic institutions and promote public-private partnerships.[72]

The second Indus X summit took place on 20-21 February 2024 in New Delhi, and, besides the iDEX and the US Department of Defence, the event was coordinated by the US-India Business Council and the Society of Indian Defence Manufacturers. The event saw the selection of the prize-winners from startups that competed in the Indus-X innovation challenges related to the maritime domain launched last year.[73]

In June 2023, the General Electric (GE) company agreed to produce their GE F-414 jet engine in India jointly. Under the deal, GE will provide 80 percent technology transfer.[74] GE had initially agreed to build 99 F-404 engines for the Indian Air Force but is now looking to make 100 F 414-INS6 for India’s LCA Mk 2 and advanced medium combat aircraft (AMCA) programmes, as well as make a bid to collaborate with an Indian agency to make the AMCA Mk 2 engine. However, India remains in talks with Rolls Royce (England) and Safran (France) for developing the AMCA Mk2 engine.

A factsheet issued by the White House indicates that technology transfer will be a major factor in the bilateral relationship. In addition to collaboration in semiconductors, the two nations will develop partnerships on critical minerals, advanced telecom, space, quantum technology, and AI.[75]

Another important development was the conclusion of a Master Ship Repair Agreement (MSRA) between the US and the Larsen and Toubro shipyard in Kattupalli, near Chennai, and efforts to work out similar agreements with other Indian shipyards.[76] In September 2023, the Mazgaon Dockyards Ltd also signed an MSRA with a US government entity.[77]

In November 2023, India and the US conducted their fifth annual ‘2+2 ministerial dialogue’. A significant decision taken there was the agreement to start the joint production of Stryker, an armoured infantry combat vehicle, in India. The discussions also focused on the importance of India emerging as a maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) facilities hub for the US in the region.[78]

On 1 February 2024, the US State Department notified the US Congress of a possible foreign military sale of MQ-9B UAVs and other equipment worth US$3.99 billion. This equipment would see the armed UAV being used in its Sky Guardian and Sea Guardian versions. The related equipment included Hellfire missiles and laser small-diameter bombs.[79]

The one area where not much information is available is intelligence cooperation. Having signed the four foundational agreements, India has the hardware to share intelligence information, but on a selective basis. Reports suggest that the US helped India repel a major Chinese incursion in the Tawang area in December 2022. However, there are reasons to believe that the US also provides information on the movement of Chinese ships from the Pacific to the Indian Ocean.[80]

During the second meeting of the IndusX in New Delhi in February 2024, Indian Defence Secretary Giridhar Aramane openly acknowledged the US assistance in dealing with the situation in eastern Ladakh in 2020, noting that the one thing that had helped India “very quickly” was the “intelligence and situational awareness which US equipment and US government could help us with”. He went on to add “We expect our friend US will be there with us in case we need their support [in future]. It is a must for us and we have to do it together.” [81]

The Major Problem Areas

India-US defence ties have a long history, but apart from arms sales and military exercises, the activity is limited. Much of this had to do with the two sides’ differing goals, including as a natural outcome of the enormous asymmetry between them—India seeking US technology and trade to move up the economic ladder, with the US wanting to incorporate India into its global economic and security framework.

On the technology transfer side, there have always been issues arising from the US restrictions on exporting its technology. These also relate to the various technology denial regimes the US has created—the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), the Wassenaar Arrangement, and the Australia Group. In the past two decades India has been given concessions in several areas and has now become party to the MTCR, Wassenaar, the Australia Group, and has been given a special waiver in NSG.

Although India was granted the unique designation of Major Defense Partner in 2016, this was not clearly defined or operationalised.[82] In contrast, Pakistan's “Major non-NATO Ally” status is a US legal category and enables Islamabad to obtain a range of defence and security privileges in the US. [83]

To expand the current defence-industrial cooperation, India needs to negotiate two more agreements with the US. The first is the Security of Supply Arrangement (SOSA), and the second is the Reciprocal Defense Procurement Arrangement (RDP). These are needed to open up the US market to Indian original equipment manufacturers and suppliers.

US Congressional approval is needed to advance cooperation on jet engine technology. Earlier, India had sought the core engine or “hot section” technology under the DTTI, but this was refused, and the working group on jet engine technology was disbanded in October 2019.[84] Under the DTTI, there is also an aircraft carrier working group to discuss various aspects of aircraft carrier technology. It held its sixth meeting in February-March 2023, but there are few signs of any special progress because India is yet to decide on proceeding with its next carrier construction.[85]

While India wants the US (or any other country such as France) to provide cutting-edge technology, that is not likely to happen. There will be clear limits to the technology shared because the intellectual property of various companies is the key to their profitmaking. So, despite coming back with a revised offer, GE noted that it will have to get US government authorisation for exports. Indian media commentary says India will get 80 percent tech transfer, which most likely means it will not get the hot section technology.[86]

The Sky Guardian deal (February 2024) brought out the kind of challenges that India will have to confront with the US. Senator Ben Cardin, chairman of the powerful US Senate Foreign Relations Committee, had blocked the deal in the wake of the scandal around the alleged plot to assassinate Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, an American supporter of the Khalistan movement. It was only after Cardin lifted his hold at the end of January 2024 that the US State Department notified the deal.[d],[87]

The big problem remains the US national restrictions on exports of defence and dual-use technologies. These are regulated through a two-track system which works in a dense legal framework. First, the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) is administered by the US State Department, and it deals with items listed in the US Munitions List that have a clear military use. Compliance with ITAR requires a license from the State Department to export specific materials.[88]

The second track is the Export Administration Regulations (EAR), which are managed by the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) under the US Department of Commerce. These relate to ‘dual use’ items that have civil and military applications, which include software and technology. Here, too, a license is needed for exports.[89]

The Arms Export Control Act (AECA) is the legal framework for US arms export control, and Congressional review is also involved. The AECA of 1976 gives the US president the power to control the export of defence technology and authorizes the US to sell and export these with certain conditions. It also specifies non-proliferation and human rights considerations relating to its application. Departmental oversight is exercised through the Bureau of Politico-Military Affairs of the State Department and the Pentagon’s Defense Security Cooperation Agency.

Dealing with the US on technology transfer can be a complex exercise, considering there are as many as 11 separate export screening lists run by the US departments of state, commerce, and treasury. While there is a consolidated list available, some parts of the lists may be classified. Even close allies like Australia and the UK are often given a runaround on the issue of exports of certain technologies. [90]

In 2008, India got waivers for the NSG, which enables civil nuclear trade and technology. But India, like most countries, still needs to follow most ITAR and EAR regulations. However, as a major defence partner, with the STA-1 authorisation, India has license-free access to a wider range of defence and dual-use technologies; while it does not get automatic access to all technologies, it gets faster approvals for items that still require licenses.

India is wary of any larger commitment to US defence plans, especially in relation to China. This was evident in its response to the proposal mooted in May 2023 by the US House Select Committee on Strategic Competition led by Congressman Mike Gallagher that India be offered membership in the NATO Plus 5 grouping. This grouping would comprise NATO and five US allies in the Indo-Pacific—Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Israel, and South Korea.[91] However, Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar categorically rejected the idea, saying, “NATO template does not apply to India”.[92]

India’s desire to acquire top-drawer technology does not quite match up with its current industrial capabilities. This is why, in 2012, French firm Dassault refused to agree to a technology transfer for the manufacture of the Rafale aircraft. This is also why the discussions in DTTI over jet engine technology were suspended in 2019. And even now, it remains to be seen just how the GE deal and other transfer of technology arrangements will work.

The Future of Indo-US Defence Cooperation

The SOSA and RDP will enable India to join a list of countries that are compliant with the Defence Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) or those that are presently qualified to supply significant components and parts for US military orders. The RDP is essentially a waiver of US laws that otherwise restrict the federal government from procuring goods from non-domestic sources. This could provide big opportunities for Indian companies to become ancillary producers for the US industry.

However, India is still some distance from becoming part of the US National Technology Industrial Base (NTIB), which is a legal category established by the US law. This places countries like Canada, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand in a special category for supplying military operations, conducting advanced research and development (R&D), and systems development to ensure the technology dominance of the US armed forces. They are also involved in securing reliable sources of critical materials and industrial preparedness of the US in the event of a national emergency.[93]

The US is seeing its promotion of DTTI and iCET with India as part of an effort to expand defence cooperation partnerships with non-NTIB countries. Notably, countries like Japan, South Korea, and Israel are also not members of the NTIB.

Conclusion

In geopolitical terms, India is sui generis (of its own kind). It is not a treaty ally of the US, and unlike Australia, Japan, and South Korea, the US is not its principal security provider. Whatever the US may have desired, India has clearly drawn some lines in its security ties with the US. India does not fully subscribe to the notion of a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ as its Quad partners do. Neither does it see eye-to-eye with the US on Pakistan, Iran, or Russia.

India-US defence relations are moving forward step by step and are currently supervised at the bilateral 2+2 ministerial level, accompanied by a dense number of working groups and bilateral interaction at all levels. It could, in the future, also be stepped up to the trilateral level following the pattern in the Asia Pacific where groups like Australia-Japan-US have emerged. Indeed, efforts are ongoing to create South Korea-US-Japan, India-Australia-US, India-US-Japan groups.

In recent years, the US, too, seems to have realised that India’s value stems from its unique status. A State Department fac sheet terms the India-US relationship as “one of the most strategic and consequential of the 21st century.”[94] This is the reason why the US continues to cut India considerable slack when it comes to areas where views diverge.

As the US sees it, India is unlikely to play a military role in the western Pacific Ocean, but an economically prosperous India dominating the Indian Ocean will itself be a factor in the balance against China without necessarily being an ally.

As for the US, it is moving along a new trajectory, the so-called New Washington Consensus, and taking what could be transformative steps in its economic and security policies, emphasising the latter's importance. In April 2023, US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan called for the forging of a new consensus based on a modern American industrial strategy. This would, first, focus on innovation and competition in areas like semiconductors, clean energy technology, and so on. Second, it would include American partners in building capacity and resilience. Third, it would seek to replace the existing trading system with “innovative new international economic partnerships” that would not focus on tariffs alone. The fourth pillar would be massive investments in emerging economies to develop energy, physical and digital infrastructure by updating the operating models of existing development banks.[95]

Clearly, the US sees India as a partner in this scheme of things. However, given India’s scarce financial resources, weakness in manufacturing technology, and backwardness in R&D, it will be a junior partner.

In any case, after its experience with China, the US will guard its technologies carefully.

The last and key pillar of Sullivan’s plan is to protect the US’s “foundational technologies with a small yard and high fence.” All high-tech and foreign investments and relationships will have to pass the stringent US national security test.

There is one more issue that needs to be stated upfront. The US, as the leader and principal security partner to its numerous allies, seeks to promote interoperability of systems with them to enhance their warfighting potential. In most cases, the systems are of US origin. However, India has long wanted to be self-reliant when it comes to defence equipment for its forces. Its ambition is to become a designer, manufacturer, and exporter of defence systems, while the US is already to dominant player here. For this reason, while it imports significant quantities of its needs, it spreads them out among existing suppliers, including Russia, Israel, the UK, France, Germany, and the US. Yet, as of now, India has signed up to a range of US conditionalities and agreements that promote the use of US-origin equipment and is also ready to partner with the US in several design and industrial ventures.

What this survey of the US-India defence cooperation reveals is that the process of developing a technology partnership has been long and arduous, in great measure because of the enormous asymmetry between the two countries—the US is known for its superlative technology, and India wants to become a technology power. From a situation where requests for technology operated in an environment of “presumption of denial,” they have now reached a point where India is treated at par with the US’s NATO allies. This, however, does not mean that India or other NATO countries have unconditional or automatic access to US technology. They still operate in a dense legal environment where each request goes through the required and stringent regulatory processes.

Endnotes

[a] It was signed by US Defense Secretary William J. Perry and Indian Minister of State for Defence M. Mallikarjun.

[b] The 2+2 format is an important instrument of the US in shaping relations with allies and partners. It has had a 2+2 arrangement with Australia since 1985 and Japan since September 2000.

[c] The CTF-150 looks at maritime security operations (MSO) outside the Persian Gulf; the CTF-151 at counterpiracy; CTF-152 at MSOs inside the Persian Gulf; and the CTF153 at Red Sea maritime security.

[d] Cardin said that he approved of the deal only after the Biden Administration had assured him after months of discussions that India was thoroughly committed to investigating the failed plot to kill Pannun.

[1] Condoleezza Rice, “Promoting the National Interest,” Foreign Affairs 79, no. 1 (2000): 45-62, https://doi.org/10.2307/20049613

[2] Embassy of India, Washington DC, USA, https://www.indianembassyusa.gov.in/ArchivesDetails?id=469

[3] “U.S. - India: Civil Nuclear Cooperation,” U.S. Department of State Archive, https://2001-2009.state.gov/p/sca/c17361.htm#:

[4] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Bridging the Ocean: India Leads Relief Measures in Tsunami-Hit Areas, December 2004-January 2005, https://www.mea.gov.in/Uploads/PublicationDocs/185_bridging-the-ocean-tsunami.pdf

[5] Sunanda K. Datta-Ray, “In the Ashes of Non-Alignment, a U.S.-India Embrace,” New York Times, March 6, 1992, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/03/06/opinion/IHT-in-the-ashes-of-nonalignmenta-usindia-embrace.html

[6] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1925015

[7] “U.S.-India Economic Dialogue: U.S.-India High Technology Cooperation Group,” U.S. Department of State Archive, https://2001-2009.state.gov/p/sca/rls/fs/2006/62495.htm#:~:text=The%20U.S.%2DIndia%20High%2DTechnology,technology%20issues%20of%20mutual%20interest

[8] “United States - India Joint Statement on Next Steps in Strategic Partnership,” U.S. Department of State Archive, https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2004/36290.htm

[9] “United States and India Successfully Complete Next Steps in Strategic Partnership,” U.S. Department of State Archive, https://2001-2009.state.gov/p/sca/rls/fs/2005/49721.htm

[10] “Agreement between the United States of America and India,” Department of State, January 17, 2002, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/02-117-India-Defense-GSOIA-1.17.2002.pdf

[11] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://archive.pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=149322

[12] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=183300

[13] “India-US Sign BECA Empowering India’s Military Valour,” Economic Diplomacy Division, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, October 26, 2020, https://indbiz.gov.in/india-us-sign-beca-empowering-indias-military-valour/; Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1797511

[14] “New Framework for the U.S-India Defense Relationship,” http://library.rumsfeld.com/doclib/sp/3211/2005-06-28%20New%20Framework%20for%20the%20US-India%20Defense%20Relationship.pdf

[15] “US to Help Make India a ‘Major World Power’,” China Daily, March 26, 2005, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2005-03/26/content_428361.htm; “U.S. Unveils Plans to Help India Become a “Major World Power”,” Wiki News, March 26, 2005, https://en.wikinews.org/wiki/U.S._unveils_plans_to_help_India_become_a_%22major_world_power%22

[16] “Joint Statement by President George W. Bush and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh,” U.S. Department of State Archive, https://2001-2009.state.gov/p/sca/rls/pr/2005/49763.htm

[17] Embassy of India, Washington DC, USA, https://www.indianembassyusa.gov.in/ArchivesDetails?id=1608

[18] Suhasini Haidar, “Tracing the Arc of American ‘Exception-ism’ for India,” The Hindu, June 28, 2023, https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/tracing-the-arc-of-american-exception-ism-for-india/article67016550.ece#:~:text=The%20Obama%20visit%20to%20Delhi,in%20Arms%20Regulations%20(ITAR)

[19] “India-U.S. Defense Technology and Trade Initiative (DTTI): Initial Guidance for Industry,” Department of Defense, Office of Prepublication and Security Review, July 14, 2020, https://www.acq.osd.mil/ic/docs/dtti/DTTI-Initial-Guidance-for-Industry-July2020.pdf

[20] Office of the Press Secretary, The White House, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2013/09/27/us-india-joint-declaration-defense-cooperation; “Inaugural U.S.-India Strategic and Commercial Dialogue,” https://in.usembassy.gov/our-relationship/policy-history/inaugural-u-s-india-strategic-and-commercial-dialogue/

[21] Office of the Press Secretary, The White House, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/01/25/us-india-joint-strategic-vision-asia-pacific-and-indian-ocean-region

[22] “Fact Sheet: U.S.-India Defense Relationship,” Department of Defense, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/US-IND-Fact-Sheet.pdf

[23] “US | India Defense Technology and Trade Initiative (DTTI),” Director, International Cooperation, https://www.acq.osd.mil/ic/dtti.html#:~:text=On%20June%207%2C%202016%2C%20President,subsequently%20been%20codified%20in%20law

[24] “Brief of India-US Relations,” Embassy of India, Washington DC, USA, https://www.indianembassyusa.gov.in/pages/MzM

[25] “U.S. Elevates India to Strategic Trade Authorization Tier 1 Status, Easing Future Dual-Use Exports,” Hughes Hubbard & Reed, August 2, 2018, https://www.hugheshubbard.com/news/u-s-elevates-india-to-strategic-trade-authorization-tier-1-status-easing-future-dual-use-exports

[26] “About iDEX,” iDEX, https://idex.gov.in/about-idex

[27] Trushaa Castelino, “U.S. Elevates India’s Defense Trade Status,” Arms Control Organization, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2018-09/news-briefs/us-elevates-indias-defense-trade-status

[28] Ministry of External Affairs, https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/32227/Joint+Statement+on+the+Second+IndiaUS+2432+Ministerial+Dialogue; Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1759911

[29] “Joint Statement on the Third U.S.-India 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue,” U.S. Embassy & Consulates in India, October 27, 2020, https://in.usembassy.gov/joint-statement-on-the-third-u-s-india-22-ministerial-dialogue/; Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=1667841

[30] U.S. Pacific Command, “U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Holds Change of Command Ceremony,” May 30, 2018, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/1535776/us-indo-pacific-command-holds-change-of-command-ceremony/

[31] “U.S. Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific,” The White House, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/IPS-Final-Declass.pdf

[32] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1759911

[33] “Joint Leaders Statement on AUKUS,” Prime Minister of Australia, September 16, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20210927191438/https://www.pm.gov.au/media/joint-leaders-statement-aukus

[34] “Quad Joint Leaders’ Statement,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, May 24, 2022, https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/35357/Quad+Joint+Leaders+Statement

[35] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1815838; https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/35184/Joint+Statement+on+the+Fourth+IndiaUS+22+Ministerial+Dialogue

[36] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1855014

[37] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1876038

[38] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1919361#:~:text=The%20sixth%20edition%20of%20Cope,culminated%20on%2024%20Apr%202023

[39] U.S. Consulate Hyderabad, “U.S., India Launch First Tiger TRIUMPH Exercise,” U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, November 15, 2019, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/2018116/us-india-launch-first-tiger-triumph-exercise/

[40] “Tiger Triumph 2022,” Indian Navy, https://indiannavy.nic.in/content/tiger-triumph-2022

[41] “Malabar 2022 Press Brief,” Indian Navy, https://indiannavy.nic.in/content/malabar-2022-press-brief; Commander, Task Force 70 / Carrier Strike Group 5, “Japan Hosts Australia, India, U.S. in Naval Exercise Malabar 2022,” U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, November 15, 2022, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/3219459/japan-hosts-australia-india-us-in-naval-exercise-malabar-2022/

[42] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1947436

[43] “Indian Navy’s INS Satpura and P8I Participate in the RIMPAC Harbour Phase,” Indian Navy, https://indiannavy.nic.in/content/indian-navys-ins-satpura-and-p8i-participate-rimpac-harbour-phase

[44] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1800604; Commander, Task Force 71/Destroyer Squadron 15, “US Forces Participate in Indian Navy-Led Exercise Milan for First Time,” America’s Navy, February 25, 2022, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/2946520/us-forces-participate-in-indian-navy-led-exercise-milan-for-first-time/

[45] “Indian Navy’s Biggest Military Exercise ‘MILAN’ Begins in Vishakhapatnam,” All India Radio News, February 19, 2024, https://newsonair.gov.in/Main-News-Details.aspx?id=477473

[46] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1905563; U.S. Naval Forces Central Command Public Affairs, “Internation Maritime Exercise 2023 Kicks Off Operational Phase,” America’s Navy, March 2, 2023, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/3315989/international-maritime-exercise-2023-kicks-off-operational-phase/

[47] “Exercise La Perouse – 2023,” Indian Navy, https://indiannavy.nic.in/content/exercise-la-perouse-%E2%80%93-2023-1; “La Perouse Exercise,” French Embassy in New Delhi, https://in.ambafrance.org/La-Perouse-exercise

[48] “Canada, India, Japan, Korea, and the U.S. Complete Multilateral Guam-Based Exercise Sea Dragon 2023,” America’s Navy, April 6, 2023, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/3354063/canada-india-japan-korea-and-the-us-complete-multilateral-guam-based-exercise-s/

[49] “Exercise Pitch Black,” Royal Australian Air Force, https://www.airforce.gov.au/news-and-events/events/exercise-pitch-black

[50] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=145357

[51] Annual Report 2007-2008, Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://mod.gov.in/dod/sites/default/files/AR-eng-2008.pdf

[52] “India - C-130J Aircraft,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, October 27, 2011, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/india-c-130j-aircraft

[53] “India - Harpoon Block III Missiles,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, September 9, 2008, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/india-harpoon-block-ii-missiles

[54] “India - UGM-84L Harpoon Missiles,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, July 1, 2014, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/india-ugm-84l-harpoon-missiles

[55] “India - AGM-84L Harpoon Air-Launched Block II Missiles,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, April 13, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/india-agm-84l-harpoon-air-launched-block-ii-missiles

[56] The Boeing Company 2009 Annual Report, Boeing, 2009, https://s2.q4cdn.com/661678649/files/doc_financials/annual/2009/2009-annual_report.pdf

[57] “India - P-8I and Associated Support,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, April 30, 2021, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/india-p-8i-and-associated-support

[58] “India - MK 54 Lightweight Torpedoes,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, April 13, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/india-mk-54-lightweight-torpedoes-0

[59] “India - C-17 Globemaster III Aircraft,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, April 26, 2010, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/india-c-17-globemaster-iii-aircraft

[60] “Government of India - C-17 Transport Aircraft,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, June 26, 2017, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/government-india-c-17-transport-aircraft

[61] “India - Support for Direct Commercial Sale of AH-64D Block III Apache Helicopters,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, December 27, 2010, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/india-support-direct-commercial-sale-ah-64d-block-iii-apache

[62] “India - M77 155mm Lightweight Towed Howitzers,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, August 7, 2013, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/india-m777-155mm-light-weight-towed-howitzers-0

[63] “India - MH-60R Multi-Mission Helicopters,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, April 2, 2019, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/india-mh-60r-multi-mission-helicopters

[64] “India - Integrated Air Defense Weapon System (IADWS) and Related Equipment and Support,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, February 10, 2020, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/india-integrated-air-defense-weapon-system-iadws-and-related-equipment

[65] Rajat Pandit, “Amid LAC Tension, India Using Naval Assets for Land Border Surveillance,” Times of India, December 19, 2022, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/amid-lac-tension-india-using-naval-assets-for-land-border-surveillance/articleshow/96326329.cms

[66] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1751648

[67] The White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/01/31/fact-sheet-united-states-and-india-elevate-strategic-partnership-with-the-initiative-on-critical-and-emerging-technology-icet/

[68] U.S. Department of Defense, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3408336/readout-of-the-inaugural-us-india-advanced-domains-defense-dialogue

[69] “Roadmap for U.S.-India Defense Industrial Cooperation,” U.S. Department of Defense, June 5, 2023, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Jun/21/2003244834/-1/-1/0/ROADMAP-FOR-US-INDIA-DEFENSE-INDUSTRIAL-COOPERATION-FINAL.PDF

[70] “Launch of India-US Strategic Trade Dialogue,” Embassy of India, Washington DC, USA, https://www.indianembassyusa.gov.in/News?id=249871

[71] Manjari Chatterjee Miller, “What Did Prime Minister Modi’s State Visit Achieve?” Council on Foreign Relations, June 26, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/blog/what-did-prime-minister-modis-state-visit-achieve

[72] “Fact Sheet: India-U.S. Defense Acceleration Ecosystem (INDUS-X),” U.S. Department of Defense, June 21, 2023, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Jun/21/2003244837/-1/-1/0/FACTSHEET-INDUS-X-FINAL.PDF

[73] Dinakar Peri, “India Standing Up to a Bully in a Very Determined Fashion: Defence Secretary on China,” The Hindu, February 21, 2024, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-standing-up-to-a-bully-in-a-very-determined-fashion-defence-secretary-on-china/article67871499.ece; U.S. Department of Defense, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3682879/fact-sheet-india-us-defense-acceleration-ecosystem-indus-x/

[74] General Electric, https://www.ge.com/news/press-releases/ge-aerospace-signs-mou-with-hindustan-aeronautics-limited-to-produce-fighter-jet-0

[75] The White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/06/22/fact-sheet-republic-of-india-official-state-visit-to-the-united-states/

[76] PTI, “Strategic Partnership. L&T Signs Master Ship Repair Agreement with US Navy,” The Hindu Business Line, July 12, 2023, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/companies/lt-signs-master-ship-repair-agreement-with-us-navy/article67070313.ece

[77] “Mazagon Dock Signs Master Ship Repair Agreement with US Govt; Shares Hit 52-Week High,” Moneycontrol, September 8, 2023, https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/markets/mazagon-dock-signs-master-ship-repair-agreement-with-us-govt-shares-hit-52-week-high-11330471.html

[78] “Joint Statement: Fifth Annual India-U.S. 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue,” Ministry of External Affairs, November 10, 2023, https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/37252/Joint_Statement_Fifth_Annual_IndiaUS_22_Ministerial_Dialogue

[79] “India - MQ-9B Remotely Piloted Aircraft,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, February 1, 2024, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/india-mq-9b-remotely-piloted-aircraft

[80] Peter Martin and Jenny Leonard, “U.S. Weaves Webs of Intelligence Partnerships Across Asia to Counter China,” Time, October 5, 2023, https://time.com/6320722/us-asia-intelligence-partnerships-china/

[81] Rajat Pandit, “Forces Standing Up to ‘Bully’: Defence Secretary Giridhar Aramane on China,” Times of India, February 22, 2024, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/forces-standing-up-to-bully-china-defence-secretary/articleshow/107893452.cms; Peri, “India Standing Up to a Bully in a Very Determined Fashion”

[82] Richard Verma and Samir Saran, Strategic Convergence: The United States and India as Major Defence Partners, The Asia Group and Observer Research Foundation, June 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/research/strategic-convergence-the-united-states-and-india-as-major-defence-partners-52364/

[83] U.S. Department of State, https://www.state.gov/major-non-nato-ally-status/

[84] Dinakar Peri, “India, U.S. Cooperation on Jet Engines ‘Suspended’,” The Hindu, October 25, 2019, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-us-cooperation-on-jet-engines-suspended/article29787788.ece

[85] Ministry of Defence, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1904172

[86] PTI, “GE Aerospace-HAL Deal to Entail 80% Transfer of Technology to India: Official,” The Print, June 24, 2023, https://theprint.in/india/ge-aerospace-hal-deal-to-entail-80-transfer-of-technology-to-india-official/1640170/

[87] PTI, “Senator Cardin Says He Backed Drone Deal with India After `Painstaking Discussions’ with Biden Admin,” The Economic Times, February 3, 2024, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/senator-cardin-says-he-backed-drone-deal-with-india-after-painstaking-discussions-with-biden-admin/articleshow/107377490.cms?

[88] Tim O’ Callaghan and Travis Shueard, “ITAR 101 – Fundamentals and Practice,” PiperAlderman, June 21, 2022, https://piperalderman.com.au/insight/itar-101-fundamentals-and-practice/

[89] “Regulations,” Bureau of Industry and Security, https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/regulations/export-administration-regulations-ear

[90] Biswajit Dhar, “Modi’s US Technology Transfer Deals May Stumble on Export Controls,” The Wire, July 8, 2023, https://thewire.in/security/modi-tech-transfer-deals-may-stumble-on-export-controls

[91] “Ahead of PM Modi’s Visit, US Panel Suggests NATO Plus Status for India,” DD News, August 7, 2023, https://ddnews.gov.in/international/ahead-pm-modis-visit-us-panel-suggests-nato-plus-status-india

[92] “‘India Capable of Countering Chinese Aggression’, Refuses to Join NATO, Says S Jaishankar,” Livemint, June 9, 2023, https://www.livemint.com/news/india-capable-of-countering-chinese-aggression-refuses-to-join-nato-says-s-jaishankar-11686288765836.html

[93] “Subpart I—Defense Industrial Base,” https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title10/pdf/USCODE-2021-title10-subtitleA-partV-subpartI-chap381-sec4801.pdf

[94] U.S. Department of State, https://www.state.gov/united-states-india-relations/#:~:text=The%20relationship%20between%20the%20United,and%20prosperous%20Indo%2DPacific%20region

[95] The White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/04/27/remarks-by-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-on-renewing-american-economic-leadership-at-the-brookings-institution/

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV