-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Is India stepping into global and regional leadership mode?

Recent reports have revealed that there are growing concerns in Nepal about China’s encroachment along their shared border. The Nepalese government has not come out publicly on this issue but it had commissioned a report last year that is warning the Himalayan nation about Chinese designs in the district of Humla in the west of the country.

In a way, it should not be surprising. China has been asserting itself all around its periphery. Nations, big and small, have come under its pressure. But it is in South Asia this territorial aggression is in full swing as Beijing seeks to position itself as a challenger to the regional dominance of India.

The consequences of China’s growing footprint and its deleterious consequences are also equally visible in South Asia today. Sri Lanka’s economic dependence on China has resulted in a peculiar debt-ridden relationship where mounting debt due to heavy borrowing from China has made the future of a once vibrant economy rather parlous.

Most of the big projects supported by China have had a deleterious impact on Sri Lanka’s future. Chinese investments in various infrastructure projects in Sri Lanka under the controversial Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have been a bane for the island nation. The much touted Hambantota port had to be handed over to a state-run Chinese firm in 2017 for a 99-year lease as a debt swap amounting to USD 1.2 billion.

Sri Lanka’s economic dependence on China has resulted in a peculiar debt-ridden relationship where mounting debt due to heavy borrowing from China has made the future of a once vibrant economy rather parlous.

It was India that had to bail out Sri Lanka with fertilizers after a Chinese company, Qingdao Seawin Biotech Co Ltd, supplied contaminated organic fertilizers, which led to the cancellation of the order. While the Chinese company rejected the allegations, Colombo argued that the samples were infected with a deadly bacteria called Erwinia which destroys crops and refused to allow a ship carrying 20,000 tons of organic fertilizers from China to offload the consignment.

New Delhi promptly sent two IAF C-17 Globemaster aircrafts with 100,000kg of Nano Nitrogen to expedite the availability of fertilizer to the Sri Lankan farmers. On the other hand, a furious Beijing responded by blacklisting the People’s Bank of Sri Lanka for failing to make a payment due to a ban imposed by a local court.

In December 2021, Sri Lanka had thus requested India for new currency swaps and financial assistance worth 1.5 billion US$. It had also cancelled the Chinese projects in the Jaffna peninsula and offered India to modernize the Trincomalee oil tank farm. And in January 2022, immediately after Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to the island nation, the Sri Lankan Finance Minister, Basil Rajapaksa visited India again for a currency swap and a deferral offer worth $900 million. During his visit to India recently, Sri Lankan Foreign Minister GL Peiris underlined that India’s support has made a “world of difference” to Sri Lanka's economic situation.

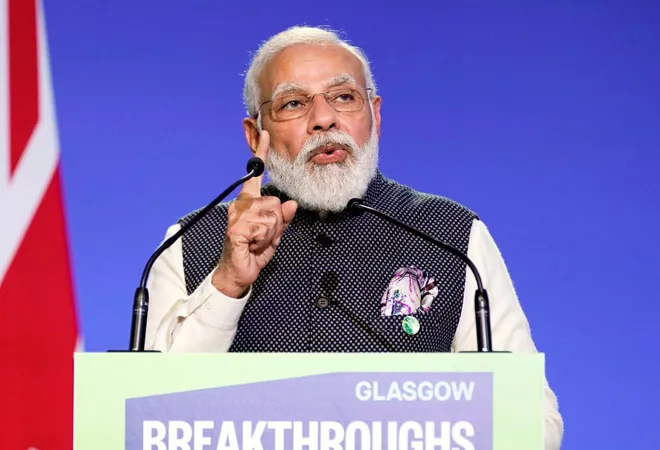

And it is in this context one has to examine New Delhi’s pro-active foreign policy outreach not only to its immediate neighbours but to the wider world. In the global order fundamentally transformed by the Covid-19 pandemic, India has been able to approach its global and regional engagement firmly rooted in the philosophy of “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam.” India today seeks a role in the international system as a “leading power” that is both willing and able to shape global and regional outcomes.

Calling for a coordinated response among the SAARC neighbours to effectively combat coronavirus in the region, New Delhi proposed the creation of a Covid-19 emergency fund with India making an initial contribution of $10m.

Even at a time when the world is consumed with internal problems and most countries have been focusing more and more inwards to fight the viral contagion, India decided to challenge these assumptions when Modi called the SAARC nation conference on Covid-19. Calling for a coordinated response among the SAARC neighbours to effectively combat coronavirus in the region, New Delhi proposed the creation of a Covid-19 emergency fund with India making an initial contribution of $10m.

Despite knowing well that Pakistan would do its best to politicize even this endeavour, which it eventually did by raking up the Kashmir issue, India was categorical that it was imperative for South Asian nations to work together and that the region “can respond best to coronavirus by coming together, not growing apart.” India also led the way in the setting up of rapid response teams of doctors, specialists, and arranged for testing equipment, besides imparting online training to emergency response staff so as to build capacity to fight such challenges across the region.

This was the first time when during a crisis the world witnessed a nation rising beyond its immediate national concerns. India’s initiative came much before any other such regional initiative and drew a positive response not only from regional states but also from countries like the US and Russia as well as the WHO. Modi also became the first global leader to call for a G20 summit via video conferencing to advance “a coordinated response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its human and economic implications.”

With South Africa, it even worked at the WTO for the dilution of intellectual property rules in tackling Covid-19, only to be opposed by the world’s most privileged.

From supplying hydroxychloroquine to more than 100 countries to providing 64 million doses of vaccines to more than 80 nations (under grants, commercial contracts and the COVAX facility), India’s imprint on global health has been highly substantive. And as the Gulf nations got hit hard as result of several nations banning food exports and declining oil demand, India ensured uninterrupted supply of food and essential items from India to the Gulf.

Where some of the richest and most powerful nations in the world turned inwards and erected barriers, India opened its heart and purse strings as a responsible member of the world community. With South Africa, it even worked at the WTO for the dilution of intellectual property rules in tackling Covid-19, only to be opposed by the world’s most privileged.

India’s regional engagement today is a testament to its vision of a stable, secure and prosperous South Asia and New Delhi is willing to lead with developing important partnerships with its neighbours. Delhi-Dhaka ties can be an important anchor for South Asia at a time of great turbulence. The fact that they are being nurtured by the leaders is a sign of growing maturity in South Asia.

This commentary originally appeared in Dhaka Tribune.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Professor Harsh V. Pant is Vice President – Studies and Foreign Policy at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. He is a Professor of International Relations ...

Read More +