-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Britta Petersen, “A Second-Class Funeral: Political Dynamics of the Eurozone Reforms”, Occasional Paper No. 192, May 2019, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

The common currency of the European Union has always been a heavily contested project. It was established in 1999 as an accounting currency, and Euro banknotes and coins entered circulation in 2002. But as early as 1992 when its foundations were laid through the provisions of the Maastricht Treaty, 62 German economists signed a manifesto titled, “The monetary resolutions of Maastricht: A danger for Europe”.[i] The paper, initiated by two professors at the University of Goettingen, reflects many of the German concerns about the common currency; 17 years later, these concerns remain.

Two referendums about the Maastricht Treaty in the same year, in Denmark and France, echoed these concerns. Both referendums were interpreted as a serious blow to the European integration project which was viewed as a way for the political elites to circumvent the will of their people.[ii] In its June 1992 referendum, Denmark rejected the Maastricht Treaty by a narrow margin (50.7 percent), while France accepted it with an equally slim edge (51 percent) on its turn in September. Denmark later ratified the treaty after some amendments in 1993.

The German economists warned that the lack of a “stability culture” in weaker European economies would lead to “growing unemployment (in these countries) due to lower productivity and competitiveness”.[iii] This would make “high transfer payments”[iv] necessary from stronger economies (read: Germany) to weaker ones. At the same time, they warned that “no agreements exist concerning the structure of a political union, a system with sufficient democratic legitimacy to regulate this process is lacking.”[v] The professors concluded: “The overhasty introduction of European monetary union will subject Western Europe to strong economic tensions, which could lead to a political struggle in the foreseeable future and thus endanger the goal of integration.”[vi]

While the professors could not have foreseen the global financial crisis in 2007-2008 that led to a sovereign debt crisis in Europe, their political predictions were accurate. Twenty-five years later, former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis gave a vivid description of his “battle with Europe’s deep establishment” during the Greek crisis in 2015.[vii] His assessment that the German-led “Troika” of the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) incarcerated Greece in “debtor’s prison” in order to bail out German and French banks still resonates in southern countries such as Italy and Spain and parts of the European political left.

At the same time, the EU is reeling under the onslaught of (mostly) anti-European right-wing populists, and one member state, the United Kingdom has decided to drop out.[viii] While the differences about the Eurozone governance are not the only reason for the tensions in Europe, they are among the main problems that need to be overcome if the EU wants to live up to its full potential. This paper attempts a brief analysis of the discursive political economy of the Eurozone[ix] in order to evaluate its achievements and assess the challenges ahead.

1. A Brief History of the Eurozone

In order to understand the existing conflicts in the Eurozone, it is worth looking at the history of the common currency. The first attempt to create an economic and monetary union among the member states of the European Communities goes back to an initiative by the European Commission in 1969, which set out the need for “greater co-ordination of economic policies and monetary cooperation”.[x] This was followed by the decision of the Heads of State or Government in The Hague in 1969 to draw up a plan to create an economic and monetary union by the end of the 1970s.

An expert group chaired by Luxembourg’s Prime Minister and Finance Minister, Pierre Werner, presented the first commonly agreed blueprint to create an economic and monetary union in three stages (Werner plan) in October 1970. The project suffered serious setbacks from the crises arising from the collapse of the Bretton Woods System[xi] as well as the rising oil prices in 1972. An attempt to limit the fluctuations of European currencies, using the so-called “snake in the tunnel”[xii] system, failed.

Between 1978 and 1979 the idea of a European Monetary System (EMS) was suggested by the then German Chancellor, Helmut Schmidt and French President Valery Giscard d’Estaing; it was agreed upon. The EMS was an adjustable exchange rate regime that aimed at improving the position of Europe within the international monetary system. It was used until the end of 1998, when it was replaced by the Euro. During this time, the German Mark (D-mark) was one of the world’s most stable currencies and became the unofficial anchor currency of the EMS. The strength of the German Mark was a result of a stability-oriented monetary policy by the German central bank, the Bundesbank. It became a matter of pride in West Germany to the extent that it gave birth to the term “D-mark-nationalism”.[xiii] The importance of the D-mark for the post-war West-German psyche had a strong echo in the discussion over the Euro in Germany and the fear of a weak Euro as opposed to the strong D-mark.

In France, on the other hand, the strength of the German Mark and the relative weakness of the French Franc led to much frustration and discussions about leaving the EMS in the early 1980s. The Keynesian economic policy of the French government at that time increased the pressure on the Franc and led to conflicts with the German government over a revaluation of both the currencies. These conflicts made the idea of a single currency with a multilateral central bank an attractive alternative.[xiv]

The debate on EMU was relaunched at the Hannover Summit in June 1988, when the Delors-Committee of the central bank governors of the 12 European member states, chaired by the President of the European Commission, Jacques Delors, was asked to propose a new timetable for creating an economic and monetary union. The “Delors report” of 1989 set out a plan to introduce the EMU in three stages and it included the creation of institutions like the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), which would become responsible for formulating and implementing monetary policy.

The three stages for the implementation of the EMU were the following:

1990– 1993: On 1 July 1990, exchange controls were abolished and capital movements completely liberalised in the European Economic Community. The “Treaty of Maastricht” from 1992 established the completion of the EMU as a formal objective and set a number of economic convergence criteria, concerning the inflation rate, public finances, interest rates and exchange rate stability. The treaty entered into force on 1 November 1993.

1994– 1998 The European Monetary Institute was established as a forerunner to the European Central Bank, with the task of strengthening monetary cooperation between the member states and their national banks, as well as supervising ECU banknotes.[xv] In June 1997, the European Council adopted in Amsterdam the “Stability and Growth Pact”, designed to ensure budgetary discipline after the creation of the Euro, and a new exchange rate mechanism (ERM II) was set up to provide stability above the Euro and the national currencies of countries that have not yet entered the Eurozone. In May 1998 the 11 initial countries that participated in the third stage from 1 January 1999 were selected at the European Council in Brussels. In June 1998, the European Central Bank (ECB) was created, and on 31 December 1998, the conversion rates between the 11 participating national currencies and the Euro were established.

1999– present From the start of 1999, the Euro was a real currency, and a single monetary policy was introduced under the authority of the ECB. A three-year transition period began before the introduction of actual Euro notes and coins, but legally the national currencies already ceased to exist.

Briefly before this, in 1998 another protest-paper signed by 155 German professors of economics was published under the title, “Der Euro kommt zu frueh (The Euro comes too early)”. The economists suggested to postpone the introduction of the common currency based on the observation that budgetary discipline was lacking in most countries–primarily, Italy and France but also Germany). Lack of budgetary discipline would lead to “the expectation of a weak Euro” and constitute a heavy burden for the monetary union.[xvi] The concern of the economists came too late, and within less than a year, the Euro was reality.

The long political process that led to the Euro was accelerated by the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, although many of the details would only become public much later. In 2002, former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl admitted in an interview (well after the end of his active political career): “In the case of introducing the Euro, I was like a dictator”.[xvii] Kohl said that he was aware he would easily lose a referendum about the introduction of the common currency in Germany. He was convinced, however, that the Euro was “a unique opportunity for the peaceful convergence of Europe” and therefore ready to “link my existence to this political project”.[xviii]

Hefty conflicts between his government and its European allies over the prospect of German re-unification preceded Kohl’s idealistic position. It is well-known that neither France nor Britain were enthusiastic about the idea of a united Germany.[xix] Lesser known is the fact that leading European politicians considered the introduction of the Euro as the price that Germany had to pay to France for unification. Former German Minister of Finance Peer Steinbrueck, a Social Democrat, remarked in an interview in 2010: “Giving up the D-mark for the (equally) stable Euro was one of the concessions that helped pave the way for German unification.”[xx] The same article quotes the former adviser to French President François Mitterand, Hubert Védrine as having said: “Mitterand did not want (German) re-unification without progress in European integration. The only terrain that was prepared was the currency.”

While leading German politicians such as former Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble (CDU) furiously deny the existence of “such a deal”,[xxi] the episode proves that there is much more to the quarrel about reforms of the Eurozone than economic theory and differences about technical financial proposals. The introduction of the common currency was a project pushed through by Europeans who tried to seize a historical moment. However, this left many questions and concerns unanswered.

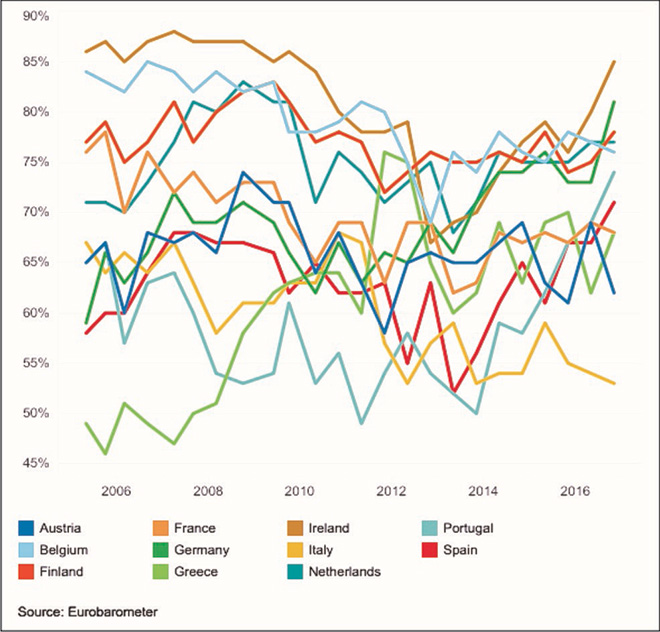

As an effect of this democratic deficit at the beginning, a widespread consensus about the common currency was largely missing. It therefore must be seen as a success story, that today support for the Euro is astonishingly high in all member states. According to a recent poll, 76 percent of Germans believe that the Euro has been good for their country; equally optimistic are France (64 percent), Spain (65 percent), and even Greece (57 percent) and Italy (45 percent).[xxii]

Figure 1. Euro Support in the Biggest Eurozone Countries

The author of a study published by the Spanish think tank Elcano, Miguel Otero-Iglesias, argues that “the Euro is popular due to positive factors: because it facilitates economic exchanges and because it is one of the most potent symbols of European integration.”[xxiii] In short, it helped “to create a sense of community”[xxiv] among the member states and the people. While these might well be the reasons why the existence of common currency is not at stake at the moment, a consensus about the governance of the Eurozone remains elusive.

II. The political Discourse Around the Eurozone

The discourse about Eurozone governance is divided along two lines that are partly overlapping: different traditions of dealing with the economy in Northern and Southern European countries; and different economic theories and goals of the political Left and Right. Generally, national discourses play a larger role than political or ideological affiliations. A reason for this might be the fact that Europe, as result of language barriers, does not have a common public sphere. Media in national languages such as German, French, Spanish, Italian, Greek, Polish or Hungarian report in very different ways about the world and the EU. This tends to reinforce the divides instead of contributing to solutions. To begin with, contradictory national discourses about the Eurozone make it extremely difficult to arrive at a compromise, even when the media are not fired up by populist sentiments.

National differences in dealing with the economy have found expression in two German words that have entered the discourse about the Euro: “Stabilitaetskultur (stability culture)” and “Transferunion (transfer union)”. This is not surprising given the fact that Germany is the largest economy in Europe and therefore has the power to define the semantics of the discourse. While stability culture in the German understanding is the desired gold standard for the Eurozone, transfer union has become a kind of “bete noir” of the political-economic discourse in Germany.

Since the introduction of the Euro, European monetary policy has followed the German tradition of keeping a stable monetary value to avoid inflation rates of more than two percent. Based on the political discourse at the inception of the common currency as described earlier, this so-called stability culture was a precondition for Germany to enter the Euro. At the time the Maastricht Treaty was signed in 1992, price stability had emerged as the sole objective of German monetary policy.

The emphasis on stability culture is based in German history as well as on the dominance of one school of macroeconomics that continues to influence economic thinking in Germany: Ordo-liberalism.[1] The traumatic experience of hyperinflation in Germany during the “great depression” in 1923 played an important role when economic and monetary policy was drafted in West-Germany[xxv] after World War II. The fact that people lost their hard-earned savings due to inflation, influenced the German preference for a reliable economic and monetary policy. The trauma also created a feeling of deja-vu during the economic crisis in 2008 and 2009, when Germans were under the impression that they had to bail out their less efficiently working partners in Southern Europe.[xxvi]

Since then, a transfer union that would force German taxpayers to fund others’ deficits for example through the introduction of Eurobonds, became the specter that haunted the German discussion about Eurozone reforms. This prompted Mario Monti, former Italian Prime Minister, who himself introduced austerity measures in Italy during his tenure, to say thus: “Economics is seen as a branch of moral philosophy in Germany.”[xxvii] Monti opines that “Germans believe economic growth is a reward for ethical behavior” because the German language uses the same word for debt (Schulden) and guilt (Schuld).

Outside Germany, stability culture was never the top economic priority. In countries such as France and Italy, higher inflation rates were accepted as a policy-tool to increase economic growth at least in the short term and reduce unemployment.[xxviii] According to Guntram B. Wolff of the Brussels-based economic think tank Bruegel, political conflicts about the distribution of wealth in Italy were usually solved by state-borrowing and the resulting higher deficits were financed through a depreciation of the Italian lira and inflation. “Italy always had a ‘soft currency’ tradition,” says Wolff.[xxix]

With the introduction of a monetary union, Europe disposed the possibility of currency devaluation, which is seen by many economists as a root cause for the growing economic imbalance between Northern and Southern Europe. American economist Kenneth Rogoff called the Eurozone “a half-built house” because it set up monetary union before reaching a fiscal and political union that would provide other tools for the EU to solve a financial crisis or even balance out differences between stronger and weaker European economies.

Based on the connection between inflation, expansive monetary policy and the independence of the central bank, Germany also consistently argues in favour of a central bank that is free from political influence. The European Central Bank (ECB) has been modeled on the German Bundesbank and is not by accident based in Frankfurt/M. In France, on the other hand, the central bank traditionally plays a role that well goes beyond securing monetary stability.

These differences are not only a result of economic schools and ideologies but are based on political realities and economic interests. For one, France is a strong central state with a powerful president whose authority is often challenged by street power seen as an expression of the French “revolutionary” spirit. (Emmanuel Macron is currently going through an intense phase of street-rebellion against some of his domestic reforms.[xxx]) Germany, on the other hand, as a federal state has strong regional political leaders backed by successful large and mid-size companies (the famous German “Mittelstand”). Its policy-process therefore heavily relies on a negotiated consensus between the states and the central government, between industry and unions and on institutions such as the Bundesbank that are made to be impartial and beyond political bickering.

Germany traditionally has a high savings rate and is therefore naturally interested to keep its inflation rates low. Germany’s export-oriented economy prefers a stable inflation rate in order to avoid foreign exchange risk. During the Eurozone crisis, French politicians accused Germany of “national egotism”[xxxi] for demanding that all European countries follow the German example. The argument is that the German position perfectly suits its export-oriented economy, a model that cannot be duplicated by all European member states and accounts for its “beggar-thy-neighbor” policy.[xxxii]

Some have even compared Chancellor Angela Merkel with Otto von Bismarck who defeated France in the French-German war of 1870-71 and annexed the province Alsace-Lorraine. Caricatures in Greece, Italy and France showed Merkel sporting either a “Hitler”-moustache or the spiked helmet (Pickelhaube) worn by the Prussian army of the 19th century. This shows that fear of a dominating Germany still exists even as it has no relevant military power but the largest European economy instead.

The almost belligerent discourse might have surprised many, but it cannot be ignored that shadows of the violent past are still lurking behind the civilised European façade. The continent is deservedly proud of the pacifying force that the EU has been since the end of World War II, but the European project is still “work in progress”. The struggle for the right policy mix for the Eurozone has to take into account sentiments in all countries. Otherwise, the pessimist prediction that the Euro will divide Europe instead of unifying it could become a reality.

The dominance of Germany after its reunification in 1990 poses a major challenge to this process although its position is often supported by other Northern countries.[xxxiii] This brings this paper to the theory of Ordo-liberalism that is often quoted as a kind of German economic exceptionalism and the reason for Germany’s alleged inflexibility not only during the Eurozone crisis but in other questions of economic governance.

According to Eucken and Boehm, the scholars who ideated ‘Ordo-liberalism’, government should provide a rule-based constitutional framework to shape markets, but must not intervene in day-to-day economic decisions. The importance of monetary stability in Eucken’s work is often cited as proof that German macroeconomic policy follows ordo-liberal thinking. While on the theoretical level, there is much more to say about Ordo-liberalism[xxxiv] and how it shaped German economic thinking, it undeniably keeps on influencing decision-makers in Germany, even when their political decisions are guided by other factors, too. Eucken’s constitutive principles explain German resistance against joint liability within the Eurozone.

It is also important to note that the Ordo-liberal emphasis on stability culture provides a valuable strategic resource for securing German objectives within the Eurozone while satisfying the requirements of domestic politics as well. Sebastian Dullien and Ulrike Guerot have pointed out that Germany’s rigidity is not just about national interest and the possible psychological scars of the Weimar-era hyperinflation. “It is about a broadly held belief in the foundations of economic success” based on “sustainable economic growth” as proven in Germany’s own success story. “Mainstream German opinion believes that harsh austerity measures are the key to breaking the cycle of debt and the threat of insolvency, reassuring the private sector and thus triggering natural and sustainable growth. Arguing about this will not change their mind.”[xxxv]

This is even true in large parts of the political left in Germany. The embattled Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis describes in his book, “Adults in the Room”[xxxvi] how he would receive moral support for his demand to write down Greek debts from leading German Social Democrats in informal meetings, but this never materialised in negotiations with the “Troika”. One reason is that the SPD is a junior partner in the German government and has less influence than Angela Merkel’s CDU, but it is also true that leading Social Democrats simply do not disagree enough with mainstream economical thinking in Germany. Varoufakis’ assumption that a conservative consensus in Europe did not want the leftist government in Athens to succeed, is therefore over-simplified until one wishes to see most social democratic parties—such as the German SPD or Spanish PSOE—no longer as “leftist” but as part of a neo-liberal mainstream.

While there are some “new Keynesian economists” in Germany who feel supported by British and American critics of the German approach such as Paul Krugman and Martin Wolf, there is little demand for radical change in mainstream political parties, be it right- or left-center. The French economist Thomas Piketty accuses both, Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron of a “hyper-conservative view” regarding the problems of the Eurozone. “Ultimately, these two leaders do not wish to make any fundamental changes in present-day Europe because they suffer from the same form of blindness. Both consider that their two countries are doing quite well and they are in no way responsible for the ups and downs of Southern Europe.”[xxxvii]

The political left in most European countries has so far been unable to benefit from the crisis or formulate credible policy alternatives that can find majorities. While most social democratic parties have abandoned the “third way” that was propagated in the wake of the new millennium by then British Prime Minister Tony Blair and German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, most of them have been unable to come up with new ideas on how to redefine “social justice” in a global economy. The idea to reconcile right-wing and left-wing politics as formulated by theorist Anthony Giddens left the traditional clientele of social democrats, old-economy workers without political representation and materially deprived while the living-standard of the European middle class feels increasingly precarious. As a result, right-wing populists manage to reap the votes of people who are unsatisfied, which in turn pushes political discourses in many countries even harder into the narrow gauges of nationalism.

The problem is aggravated by the fact that Europe does not have a common public sphere due to different national languages. Political discourses that are naturally dominated by national political parties and their interests remain deeply entrenched in their own country.

In a comparative study[xxxviii] by the European economic think tank Bruegel, a team of researchers analysed narratives of the Eurozone crisis in four different European countries: Germany, France, Italy and Spain. Together these four countries account for three-quarters of the Eurozone and the European GDP. The Bruegel team picked one leading newspaper from each country and created a database of more than 50,000 articles that appeared over ten years between the beginning of the Eurozone crisis and 2018.

All the four newspapers (Sueddeutsche Zeitung/Germany, Le Monde/France, La Stampa/Italy, El Pais/Spain) are center-left in the political spectrum, elite-papers that have a significant influence among decision-makers. The study concludes that, “Sueddeutsche Zeitung blames everyone but Germany” for the crisis, “the chief suspects being Greece and the European Central Bank.”[xxxix] “Le Monde blames everyone including the French political class.”[xl] “La Stampa sees Italy as the victim of unfortunate circumstances including the European Union austerity measures promoted by Germany and Italy’s own politicians” and “El Pais primarily blames Spain for misconduct during the boom years preceding the crisis.”[xli]

While these newspapers are not representative of the political discourse in their respective countries as a whole, the Bruegel analysis is relevant because it shows the almost absolute dominance of national discourses that “impedes the emergence of a common body of public opinion as the basis for debate around the reform agenda for the euro area as a whole.”[xlii]

III. Reform Suggestions and Their Political Fate

This became clear not only during the Greek crisis but during the Eurozone reform process in 2018 as well, where several serious proposals were under discussion.

Some 14 economists from France and Germany presented a reform paper for the European Monetary Union, titled, “How risk sharing and market discipline can be reconciled: A constructive proposal for euro area reform”.[xliii] In essence, it suggests a combination of risk-sharing among member states with more fiscal discipline to make the Euro area more robust and crisis-resistant in the future. It proposes, among others, a new joint fund to support individual countries in the event of major economic crises. All countries are to pay into this fund to receive financial support in times of crisis. The contributions will be based on the economic performance of a country, and the benefits drawn from the fund do not have to be repaid directly. However, a claim will lead to higher contributions in the future. This proposal can be described as an insurance solution.

A different group of 14 economists argues that the Franco-German proposal neglects the fact that if the Euro does not succeed economically it will become politically unsustainable. [xliv] The other left-of-center authors therefore put institutional and political issues at the heart of the reform debate. A new political approach would include a European executive that is democratically accountable before a parliament of the Eurozone. This would require a sizeable Eurozone budget which would perform five critical functions: be a credible backstop to the financial system; enable stronger macroeconomic stabilisation in the event of shocks; provide the ability to raise taxes; decide on expenditures and issue debt; and help create a new form of cohesion and convergence for member states in trouble.

Both papers were as controversially discussed as another idea that the German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz (a Social Democrat) and his French counterpart Bruno Le Maire (Center-Right) introduced in June 2018: a joint European unemployment insurance scheme. This would also be a fund, into which all countries pay in order to be able to receive financial support for their own national unemployment insurance in times of crisis. The contributions will presumably be proportionate to a country’s economic performance. In contrast to the proposal of the French and German economists, this approach is designed to pay back the benefits received later. It can therefore also be described as a credit-solution. The decisive factor for the realisation of the approach of Scholz and Le Maire is the mandatory repayment of the benefits received from the joint fund, but economists remain skeptical that an obligation to repay the services received can be realised.

After several meetings between the European leaders, especially between Merkel and Macron in Meseberg and the EU summit in June 2018 in Brussels, none of the high-flying plans of the French president could find enough support in the Euro-Group. Macron’s suggestion to create a separate budget for the Eurozone, managed by a European Finance Minister, fell flat, along with the idea to transform the ESM into a European Monetary Fund. The official statement of the summit consists of merely four bullet points on half a page of A-4- paper.[xlv] The Brussels-based journalist Eric Bonse spoke of a “second class funeral” for the ideas of Macron.[xlvi]

Even though Angela Merkel had principally agreed to a Eurozone budget, which was celebrated as a breakthrough, the devil lies in the detail. Merkel’s idea for the budget amounts to less than one percent of the Eurozone’s GDP—and that is surely too small to be of great help in another financial crisis. In reality, a budget that is subject to democratic control through the European Parliament and financed through a common taxation system, would require a level of European integration that is still far from political reach. Thomas Piketty therefore criticised Macron for not being serious enough, because the French president never concretised his proposals. He thus left the door wide open for the Germans to call his demands nothing more than a bluff.[xlvii]

However, before Christmas in 2018 the EU wanted to present some good news. On December 4th, the president of the Euro-Group and Finance Minister of Portugal, Mario Centeno announced at a press conference in Brussels: “We have a deal.”[xlviii] Pierre Moscovici, EU Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, who stood right next to him, was less enthusiastic. After 16 hours of negotiations, “only small steps” could be made, said Moscovici.[xlix]

The finance ministers of the Euro-Group agreed on a number of reform elements to strengthen the monetary union. The focus is on expanding the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), which was established as a crisis fund. In accordance with the settlement proposal, the ESM will be given further powers, will be further expanded, and can in the future extend loans to the single bank settlement fund. In addition, it was agreed that there should be approaches to an insolvency order for over-indebted states, with the ESM moderating negotiations between creditors and debtors. Further steps regarding the introduction of a common European deposit guarantee will not be discussed before the European Parliament elections in May 2019.

In an opinion poll conducted by a German think tank for economics, 56 percent of the participating economists said that they are “not satisfied” with the agreed steps, only 29 percent expressed satisfaction and 15 percent were indecisive.[l]

This is not surprising given the fact that the Euro-Group is not a democratically legitimised institution but an informal body consisting of the ministers of the Euro area. During the Eurozone crisis, it gained disproportionate power.[li] It might be exactly the above-mentioned kind of non-transparent “backdoor solutions” that contribute to the alienation of many citizens with the European Union without actually helping much to improve the governance of the Eurozone.

Conclusion: Whither the Euro?

This leaves the Eurozone ill-prepared for a possible recession or even another economic crisis that could set in as early as 2020. The writing is already on the wall with increased economic nationalism and trade wars.[lii]

The institutional framework that emerged for economic policy following the Maastricht treaty was incomplete and imbalanced; it remains so because the underlying aim of political unification has yet to be fulfilled. Economists warned right from the start that introducing the Euro would be putting the proverbial cart before the horse. Joseph E. Stieglitz believes “the Euro was a system almost designed to fail.”[liii] “It took away governments’ main adjustment mechanisms (interest and exchange rates): and, rather than creating new institutions to help countries cope with the diverse situations in which they find themselves, it imposed new strictures – often based on discredited economic and political theories – on deficits, debt, and even structural policies.”[liv]

The European Parliament remains weak and the European Commission is not a government based on a parliamentary majority. With European elections in 2019, it is likely that right-wing populist parties will gain significantly. This and the looming Brexit make further steps towards a closer European integration in the near future almost impossible, even when they would be desirable to complete the monetary and economic union.

Nonetheless, the Euro has weathered a severe crisis. Europe, with only seven percent of the world’s population, still accounts for almost a quarter of the global economy. So far the incrementalism that has been the hallmark of the European unification process, has carried the common currency through. The attempt to speed up a political process through an economic decision has proven problematic, but the future of the EU hinges on the Euro. This might well be the reason why the Euro will survive. However, if the EU wants to live up to its full potential, it needs to find more sustainable ways to deal with the common currency, even when a “once-and-for-all” solution remains elusive.

Endnotes

[1] Ordo-liberalism is a stream of the neo-classical school of microeconomics that originates in the so-called Freiburg-School of the 1930s lead by the economist Walter Eucken and law scholar Franz Boehm. Both worked on the interdependency of legal-institutional structures and economics. They developed their ideas as a reaction to negative experiences with state interventionism on the one hand and laissez-faire-liberalism on the other at the beginning of the 20th century in Europe.

[i] The monetary resolutions of Maastricht: A danger for Europe. Frankfurt/Hamburg: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung/Die Zeit, 11 June 1992

[ii] Erik Oddvar Eriksen and John Erik Fossum (ed.) Democracy in the European Union. Integration through deliberation? London/New York: Routledge, 2000

[iii] Op.cit.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Yanis Varoufakis Adults in the Room. My Battle with Europe’s Deep Establishment, London: Random House, 2017

[viii] Britta Petersen The Brown Chamaeleon. Europe’s Populism Crisis and the Re-Emergence of the Far Right, New-Delhi: ORF Occasional Paper, February 2018

[ix] For an introduction into «discursive political economy» see: Jens Maesse “Economic experts: a discursive political economy of economics” in Journal of Multicultural Discourses, Volume 10, 2105, Issue 3, Abingdon, UK

[x] “Commission Memorandum to the Council on the co-ordination of economic policies and monetary co-operation within the Community”, Brussels: Secretariat of the Commission, 12 February 1969.

[xi] The Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates established after the end of World War II provided European countries with monetary stability for almost 30 years. For an analysis of the failure of Bretton Woods and the similarities to the current Eurozone crisis see Pierre Siklos “From Bretton Woods to the Euro: How Policy-Maker Overreach Fosters Economic Crises”, CIGI Papers: Ontario, 23 August 2012

[xii] The snake in the tunnel was the first attempt at European monetary cooperation in the 1970s, aiming at limiting fluctuations between different European currencies. It was an attempt at creating a single currency band for the European Economic Community (EEC), essentially pegging all the EEC currencies to one another.

[xiii] The term D-Mark nationalism refers to the fact that Germany after the collapse of the Nazi-regime became extremely averse to any kind of nationalism and means that West-Germany replaced national pride by a pride in its strong currency see: Juergen Habermas Der DM-Nationalismus, Hamburg: Die Zeit, 30 March 1990

[xiv] Martin Hoepner and Alexander Spielau “Better than the Euro? The European Monetary System (1979-1998)”, New Political Economy, Volume 23, Issue 2, Abington, 2018

[xv] The European Currency Unit (ECU) was a basket of currencies of the EU member states used as the unit of account before it was replaced by the Euro in 1999.

[xvi] Wim Koesters et al, «Der Euro kommt zu frueh», Frankfurt/M.: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 9.February 1998

[xvii] Jens Peter Paul Bilanz einer gescheiterten Kommunikation. Fallstudien zur deutschen Entstehungsgeschichte des Euro und ihrer demokratietheoretischen Qualitaet, Frankfurt/M.: Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universitaet, 2010

[xviii][xviii] Ibid.

[xix] According on an article in The Times, London, 11 September 2009 based on Soviet Achieves, former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher pleaded with then President of the Soviet Union, Michail Gorbachev: “We do not want a united Germany (…) such a development would undermine the stability of the whole international situation” in: www.margaretthatcher.org/document/112006). Former French President Francois Mitterand voiced his concerns by famously saying he “likes Germany so much” that he prefers to “have two of them”.

[xx] “Der Preis der Einheit“, Hamburg: Der Spiegel, 27 September 2010.

[xxi] ibid

[xxii] Leonid Bershidsky No, Italy isn’t a Victim of the Euro. The Common Currency’s Proponents have a strong Case, they just need to make it more convincingly, Bloomberg, 29 May 2018.

[xxiii] Miguel Otero-Iglesias “Why the Eurozone Still Backs Its Common Currency” in: Foreign Affairs, 12 January 2017

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] For obvious reasons, the experiences of Communist East Germany did not figure in the economic debate about the Euro and this is true for all Eastern European countries under Communist influence. The ongoing alienation of Eastern European countries from the EU is a complex process but the negligence of several decades of intellectual work and experiences surely play a role that awaits examination.

[xxvi] See: Oliver Fohrmann “Nur keine Inflation. Stabilitaetskultur aus franzoesischer und deutscher Sicht» in: Zeitschrift Dokumente/Documents 2: Bonn/Strasbourg 2012

[xxvii] “Das erste Mal, das seine Regierung die EU-regeln offen missachtet”, Interview with Mario Monti in: Die Welt: Berlin, 18 October 2018

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] Guntram B. Wolff: “Traegt Deutschland eine Mitschuld an Italiens Krise?” in Hamburg: Die Zeit, 4.Juni 2018

[xxx] Gregory Viscusi “Why the Yellow Vests remain a Thorn in Macron’s Presidency”, Bloomberg, 30 April 2019.

[xxxi] “Frankreichs Sozialisten werfen Merkel Egoismus vor”, Hamburg: Die Zeit, 27 April 2013.

[xxxii] The argument is that Germany’s large current-account-surplus as a result of wage-suppression almost forced German banks to lend money to Southern European countries, which was the main reasons for the Greek Crisis. See for example Philippe Legrain: “The Eurozone’s German Problem”, Brussels: Project Syndicate, 23 July 2015.

[xxxiii] These countries lead by the Netherlands (Ireland, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) are also sometimes referred to as “the seven dwarfs”, ‘Hanseatic League 2.0”, “countries not occupied by the Roman Empire” or the “beer drinkers” as opposed to the “wine drinkers” in the South. Ironic as these expressions might be, they still allude to long shadows of the European past.

[xxxiv] For a detailed discussion see: Lars P. Feld, Ekkehard A. Koehler, Daniel Nientiedt: “Ordoliberalism, Pragmatism and the Eurozone Crisis. How the German Tradition shaped Economic Policy in Europe” in: Freiburg i.Br.: Freiburger Diskussionspapiere zur Ordnungoekonomik, No. 15/04, 2015

[xxxv] Sebastian Dullien and Ulrike Guerot: “The long Shadow of Ordoliberalism: Germany’s Approach to the Euro Crisis”, Berlin: European Council on Foreign Relations, 22 February 2012.

[xxxvi] Varoufakis, 2017

[xxxvii] Thomas Piketty: “The Transferunion fantasy” in: Paris: Le Monde, 12 June 2018

[xxxviii] Henrik Mueller, Giuseppe Porcaro, Gerret Von Nordheim «Tales from a Crisis. Diverging Narratives of the Euro area», Brussels: Bruegel Policy Contribution, Issue no. 03, February 2018

[xxxix] ibid

[xl] Ibid.

[xli] Ibid.

[xlii] Ibid.

[xliii] Agnes Benassy-Quere, Markus K. Brunnermeier, Henrik Enderlein, Emmanuel Farhi, Marcel Fratzscher, Clemens Fuest, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Philippe Martin, Jean Pisani-Ferry, Helene Rey, Isabel Schnabel, Nicolas Veron, Beatrice Weder di Mauro, Jeromin Zettelmeyer: “How to reconcile Risk Sharing and Market Discipline in the Euro Area” in Brussels: CEPR Policy Insight No.91, 17.January 2018.

[xliv] Laszlo Andor, Pervenche Beres, Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Laurence Boone, Sebastian Dullien, Guillaume Duval, Luis Garicano, Michael A. Landesmann, George Papaconstantinou, Antonio Roldan, Gerhard Schick, Xavier Timbeau, Achim Truger, Shahin Vallee: “Blueprint for a Democratic Renewal of the Eurozone”, in: Brussels: Politico, 28.February 2018.

[xlv] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/35999/29-euro-summit-statement-en.pdf

[xlvi] Eric Bonse: “So endet die ‘Leader’s Agenda’” in: Brussels: Lost in EUrope, 7.August 2018.

[xlvii] Thomas Piketty: “The Transferunion fantasy”, ibid.

[xlviii] “Wir haben einen Deal”, Berlin: Die Welt, 4 December 2018

[xlix] Commissioner Moscovici’s introductory remarks at the Euro-Group press conference, Press release, Brussels: European Commission, 4 December 2018

[l] “Reform Proposals for the Eurozone – Is Common European Unemployment Insurance the Solution?” Munich: Economists Panel for December 2018,CESifo Group.

[li] Mehreen Khan: «Cosmetic changes won’t fix the euro’s democratic failings. Critics see the Eurogroup as a closed-door cabal with the power to make or break economies” in: Londion: Financial Times, 5 February 2019

[lii] Nouriel Roubini and Brunello Rosa, «The Makimgs of a 2020 Recession and Financial Crisis” in: Project Syndicate, 13,September 2018

[liii] Joseph E. Stieglitz: “The Euro. How a Common Currency threatens the Future of Europe”, New York: W.W.Norton&Company, August 2016

[liv] Ibid.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Britta Petersen is a German journalist and political scientist. She is currently a Senior Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation and works on India-EU relations. ...

Read More +