[1] Harsh Pant, “A Quiet but decisive shift in India’s Foreign Policy,” Livemint, January 28, 2019.

[2] Prithvi Iyer, “Analyzing global response to the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act,” Observer Research Foundation, December 26, 2019.

[3] Prateek Waghre, “What 300 Days of Internet Winter in Kashmir Tell Us About Erecting a Digital Wall,” The Wire, May 26, 2020.

[4] PTI report, “PSA Detention of Mehbooba Mufti, 2 Others Kashmiri Leaders Extended By 3 Months,” The Wire, May 06, 2020.

[5]Manveera Suri, “Protests and a weakening economy spell a rocky road ahead for India’s Narendra Modi,” CNN, January 16, 2020.

[6] Bilal Kuchay, “Fresh violence erupts in Indian capital during anti-CAA protests” Al Jazeera, February 24, 2020.

[7] Alyssa Ayers, “A Field guide to US-India Trade Tensions,” Council for Foreign Relations, February 13, 2020.

[8] EU factsheet, “South Asia Factsheet,” European Parliament, November 2019.

[9] PTI report, “India is interested in reviving FTA talks with EU: Nirmala Sitharaman”, The Economic Times, September 09, 2015.

[10] Kashish Parpiani, “India-US relations under Trump: Guarding against transactionalism by pivoting to the US legislature”, Observer Research Foundation, October 18, 2018.

[11] Sophie Tatum, “Bipartisan bill would prevent Trump from exiting NATO without Senate approval”, CNN International, July 26, 2018.

[12] TNN report, “India set to get US waiver on missile deal with Russia”, The Times of India, July 25, 2018.

[13] Aaron Mehta, “Turkey officially kicked out of F-35 program, costing US half a billion dollars”, Defense News, July 17, 2019.

[14] Michael Crowley, “Trump Vetoes Measure Demanding Congressional Approval for Iran Conflict”, The New York Times, May 06, 2020.

[15] Abigail Hess, “On a day of historic firsts, Nancy Pelosi makes history for the second time as House speaker”, CNBC, January 03, 2019.

[16] Julian Borger, “Rex Tillerson: ‘America first’ means divorcing our policy from our values”, The Guardian, May 07, 2017.

[17] HFAC release, “Human Rights in South Asia: Views from the State Department and the Region”, U.S. House of Representatives — Committee on Foreign Affairs, October 22, 2019.

[18] HFAC proceedings, “Subcommittee Hearing: Human Rights in South Asia: Views from the State Dept and the Region: Panel I”, House Foreign Affairs Committee Republicans — YouTube channel, October 22, 2019.

[19] Jesse McKinley, “Jamaal Bowman Proves Ocasio-Cortez Was No Fluke”, The New York Times, July 17, 2020.

[20] Kashish Parpiani, “US Congress hearing on Kashmir: India falls prey to American political polarisation”, Observer Research Foundation, October 25, 2019.

[21] HFAC proceedings, “Subcommittee Hearing: Human Rights in South Asia: Views from the State Dept and the Region: Panel I”, House Foreign Affairs Committee Republicans — YouTube channel, October 22, 2019.

[22] Alice G. Wells, “Statement Of Alice G. Wells, Acting Assistant Secretary, Bureau Of South And Central Asia, Before The House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee On Asia And The Pacific”, US House of Representatives, October 22, 2019.

[23] Peerzada Ashiq, “Restored mobile lines recharge residents of Kashmir”, The Hindu, October 14, 2019.

[24] Sriram Lakshman, ‘Kashmir: India caucus co-chair statement to U.S. Congressional Record supports Narendra Modi’, The Hindu, November 02, 2019.

[25] Niha Masih, Shams Irfan and Joana Slater, “India’s Internet shutdown in Kashmir is the longest ever in a democracy”, The Washington Post, December 16, 2019.

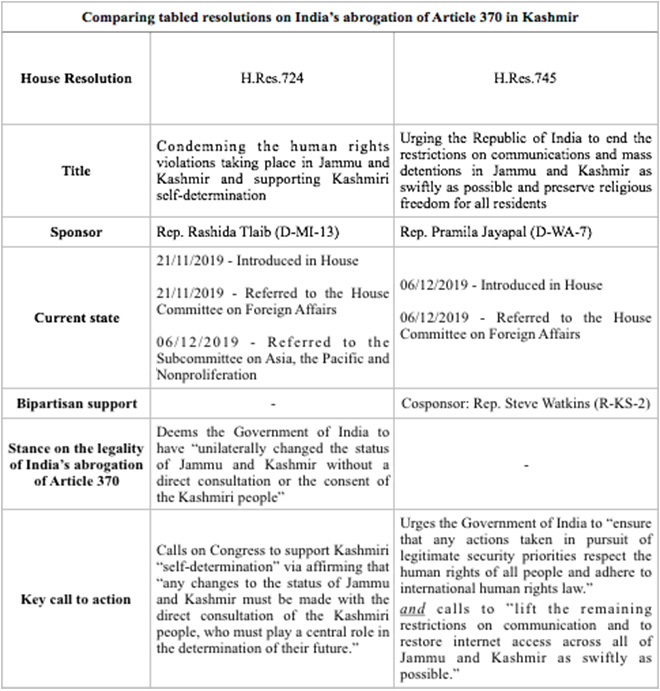

[26] Rashida Tlaib, “H. RES. 724 – Condemning the human rights violations taking place in Jammu and Kashmir and supporting Kashmiri self-determination”, 116th Congress – 1st Session, November 21, 2019.

[27] Rashida Tlaib, “H. RES. 724 – Condemning the human rights violations taking place in Jammu and Kashmir and supporting Kashmiri self-determination”, 116th Congress – 1st Session, November 21, 2019.

[28] Rashida Tlaib, “H. RES. 724 – Condemning the human rights violations taking place in Jammu and Kashmir and supporting Kashmiri self-determination”, 116th Congress – 1st Session, November 21, 2019.

[29] BT report, “Article 370 revoked: US says it’s India’s ‘internal matter’ in a blow to Pakistan”, Business Today, August 08, 2019.

[30] Pramila Jayapal, “H. RES. 745 – Urging the Republic of India to end the restrictions on communications and mass detentions in Jammu and Kashmir as swiftly as possible and preserve religious freedom for all residents”, 116th Congress – 1st Session, December 06, 2019.

[31] Pramila Jayapal, “H. RES. 745 – Urging the Republic of India to end the restrictions on communications and mass detentions in Jammu and Kashmir as swiftly as possible and preserve religious freedom for all residents”, 116th Congress – 1st Session, December 06, 2019.

[32] Pramila Jayapal, “H. RES. 745 – Urging the Republic of India to end the restrictions on communications and mass detentions in Jammu and Kashmir as swiftly as possible and preserve religious freedom for all residents”, 116th Congress – 1st Session, December 06, 2019.

[33] William Cummings, “‘The Squad’: These are the four congresswomen Trump told to ‘go back’ to other countries”, USA Today, July 15, 2019.

[34] Ella Nilsen, “Pramila Jayapal is Congress’s activist insider“, Vox, February 20, 2019.

[35] Pramila Jayapal, “H. RES. 745 – Urging the Republic of India to end the restrictions on communications and mass detentions in Jammu and Kashmir as swiftly as possible and preserve religious freedom for all residents”, 116th Congress – 1st Session, December 06, 2019.

[36] Seema Sirohi, “Kashmir issue draws Indian-Americans to Republican camp”, India Today, September 17, 2020.

[37] Seema Sirohi, “Kashmir issue draws Indian-Americans to Republican camp”, India Today, September 17, 2020.

[38] Ionel Zamfir, “Human Rights in EU trade agreements – The Human Rights Clause and its’ applications,” European Parliamentary Research Service, July 2019.

[39] Benjamin Fox, “New Human Rights Laws in 2021, promises EU Justice Chief,” Euractiv, April 30, 2020.

[40] Rajendra K. Jain, “India, the European Union and Human Rights,” India Quarterly – A Journal of International Affairs (Volume 73, Issue 4), November 08, 2017.

[41] European Parliament, “European Parliament Resolution on EU Political Relations with India,” European Parliament 014-2019 Resolutions, P8_TA(2017)0334, September 13, 2017.

[42] EEAS press release, “High Representative/Vice-President Federica Mogherini met with Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, Indian Minister for External Affairs,” Delegation of the European Union to India and Bhutan, August 30, 2019.

[43] PTI report, “S Jaishankar meets EU leaders; holds talks on terrorism, economic issues,” Hindustan Times, February 19, 2020.

[44] Nayanima Basu, “European Parliament to debate ‘Kashmir issue’ tomorrow, first time in 11 years”, The Print, September 30, 2019.

[45] EU Delegation archive, “Speech on behalf of the High Representative/Vice-President Federica Mogherini at the European Parliament plenary debate on the situation in Kashmir,” Delegation of the European Union to India and Bhutan, September 18, 2019.

[46] Suhasini Haidar, “Questions grow over NGO’s invitation to European Parliamentarians,” The Hindu, October 30, 2019.

[47] Joanna Slater, “U.S. senator blocked from visiting Kashmir as crackdown enters third month,” The Washington Post, October 05, 2019.

[48] Suhasini Haidar, “Questions grow over NGO’s invitation to European Parliamentarians,” The Hindu, October 30, 2019.

[49] Julie Ward, “Lack of political balance in an MEP delegation to Kashmir / Controversial visit to Kashmir,” Parliamentary Questions, European Parliament, January 21, 2020.

[50] Scroll report, “‘Won’t join a PR stunt’: UK politician says India revoked J&K invitation as he wanted to move freely,” Scroll India, October 29 2019.

[51] Elizabeth Roche, “EU panel to visit Kashmir today in first foreign trip since clampdown” Livemint, October 29, 2019, https://www.livemint.com/news/india/delegation-of-eu-lawmakers-to-visit-kashmir-this-week-11572253203282.html

[52] Khalid Shah and Kriti M Shah, “Kashmir After Article 370: India’s Diplomatic Challenge,” Observer Research Foundation, July 16, 2020, https://www.orfonline.org/research/kashmir-after-article-370/

[53] HT report, “European Parliament will take up resolutions opposing CAA,” Hindustan Times, 27 January 27, 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/europe-house-may-take-up-resolutions-opposing-caa/story-Ro182NUpL5rOfN4FNjQv9J.html

[54] Amie Kreppel and Micheal Webb, “European Parliament resolutions—effective agenda setting

or whistling into the wind?,” Journal of European Integration, Volume 41, No.3, 2019, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07036337.2019.1599880?journalCode=geui20

[55] FP staff report, “Six groups from European Parliament move resolution against CAA, abrogation of Article 370: A look at their ideological leanings” Firstpost, January 27, 2020, https://www.firstpost.com/india/six-groups-from-european-parliament-move-resolution-against-caa-abrogation-of-article-370-a-look-at-their-ideological-leanings-7961411.html

[56] PTI report, “’CAA Set To Create Largest Statelessness Crisis In World’: EU Lawmakers’ Resolution” Huffington Post, January 27, 2020, https://www.huffingtonpost.in/entry/caa-set-to-create-largest-statelessness-crisis-in-world-eu-lawmakers-resolution_in_5e2e5de4c5b67d8874b4ee2f

[57] The Hindu report, “Current situation in Kashmir not good and not sustainable, says Angela Merkel,” The Hindu, November 01, 2019, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/german-chancellor-angela-merkel-on-jammu-and-kashmir/article29856547.ece

[58] The Wire staff report, “Sweden joins EU, US in calling for removal of restrictions in Kashmir”, The Wire, November 11, 2019, https://thewire.in/diplomacy/sweden-kashmir-restrictions

[59] PTI report, “CAA India’s Internal and domestic matter,” Deccan Herald, December 16, 2019, https://www.deccanherald.com/international/world-news-politics/caa-is-indias-internal-and-domestic-matter-france-786042.html

[60] HT report, “What has the world said on Kashmir,” The Hindustan Times, December 11, 2019, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/what-has-the-world-said-on-kashmir/story-8NpvLoJRmy6KYbnqMrR1CI.html

[61] PTI report, “British MPs and peers clash, issue tit-for-tat letters over Jammu and Kashmir decision”, News18, August 13, 2019, https://www.news18.com/news/world/britain-mps-and-peers-clash-issue-tit-for-tat-letters-over-jammu-and-kashmir-decision-2269701.html

[62] HT report, “What has the world said on Kashmir,” The Hindustan Times, December 11, 2019, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/what-has-the-world-said-on-kashmir/story-8NpvLoJRmy6KYbnqMrR1CI.html

[63] PTI report, “European Parliament debates anti-CAA motion, vote delayed till March,” India Today, January 30, 2020, https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/european-parliament-debates-anti-caa-motion-vote-delayed-till-march-1641429-2020-01-30

[64] Huma Siddiqui, “Pakistan’s info-war post-Article 370 revocation: Here’s what experts say on information operations as a form of warfare”, Financial Express, September 02, 2019, https://www.financialexpress.com/defence/pakistans-info-war-post-article-370-revocation-heres-what-experts-say-on-information-operations-as-a-form-of-warfare/1693627/

[65] Julia Roknifard, “At Malaysia’s KL Summit, the Muslim world’s most pressing concerns got no mention”, South China Morning Post, December 24, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/3043413/malaysias-kl-summit-muslim-worlds-most-pressing-concerns-got-no

[66] Lalit K Jha, “Why Jaishankar refused to meet Pramila Jayapal”, Rediff News, December 20, 2019, https://www.rediff.com/news/report/why-jaishankar-refused-to-meet-pramila-jayapal/20191220.htm

[67] Lalit K Jha, “Why Jaishankar refused to meet Pramila Jayapal”, Rediff News, December 20, 2019, https://www.rediff.com/news/report/why-jaishankar-refused-to-meet-pramila-jayapal/20191220.htm

[68] PTI report, “Pramila Jayapal becomes first Indian-American woman to be elected to the U.S. House”, The Hindu, November 09, 2016, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/world/Pramila-Jayapal-becomes-first-Indian-American-woman-to-be-elected-to-the-U.S.-House/article16440922.ece

[69] Pramila Jayapal’s tweet, “The cancellation of this meeting was deeply disturbing. It only furthers the idea that the Indian government isn’t willing to listen to any dissent at all.”, @RepJayapal on Twitter, December 20, 2019, https://twitter.com/RepJayapal/status/1207783680623751171?s=20

[70] PTI report, “Kamala Harris decries Jaishankar’s decision of not meeting Jayapal”, The Hindu, December 21, 2019, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/kamala-harris-decries-jaishankars-decision-of-not-meeting-jayapal/article30364901.ece

[71] PTI report, “Kamala Harris decries Jaishankar’s decision of not meeting Jayapal”, The Hindu, December 21, 2019, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/kamala-harris-decries-jaishankars-decision-of-not-meeting-jayapal/article30364901.ece

[72] Kashish Parpiani and Niranjan Jose, “Understanding the resolutions on Kashmir in the US Congress”, Observer Research Foundation, December 18, 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/understanding-the-resolutions-on-kashmir-in-the-us-congress-59341/

[73] Nayanima Basu, “Why US Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal’s Kashmir resolution doesn’t have many takers”, The Print, January 07, 2020, https://theprint.in/diplomacy/why-us-congresswoman-pramila-jayapals-kashmir-resolution-doesnt-have-many-takers/345492/

[74] Congress.gov, “H. RES. 745 – Urging the Republic of India to end the restrictions on communications and mass detentions in Jammu and Kashmir as swiftly as possible and preserve religious freedom for all residents”, 116th Congress – Cosponsors, December 06, 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-resolution/745/cosponsors?searchResultViewType=expanded&KWICView=false

[75] Congress.gov, “H. RES. 745 – Urging the Republic of India to end the restrictions on communications and mass detentions in Jammu and Kashmir as swiftly as possible and preserve religious freedom for all residents”, 116th Congress – Cosponsors, December 06, 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-resolution/745/cosponsors?searchResultViewType=expanded&KWICView=false

[76] Felicia Schwartz, “Some Israelis Worry U.S. Bipartisan Political Support Is Eroding”, The Wall Street Journal, August 16, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/some-israelis-worry-u-s-bipartisan-political-support-is-eroding-11565992520

[77] Shubhajit Roy, “US Senator keen to see Kashmir ‘first hand’, denied nod”, The Indian Express, October 05, 2019, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/us-senator-chris-van-hollen-keen-to-see-kashmir-first-hand-denied-nod-6054324/

[78] Wire report, “’J&K Situation Not Normalised’: US Congress Panel Writes to Jaishankar on Article 370 Move”, The Wire, August 06, 2020, https://thewire.in/diplomacy/us-congresss-powerful-house-foreign-affairs-committee-jaishankar-kashmir-article-370

[79] PTI report, “US, India announce establishment of annual Parliamentary Exchange from 2020”, The New Indian Express, December 20, 2019, https://www.newindianexpress.com/world/2019/dec/20/us-india-announce-establishment-of-annual-parliamentary-exchange-from-2020-2078750.html

[80] Kashish Parpiani, “Cultivating the Bipartisan Consensus on India in the 116th US Congress”, Observer Research Foundation, November 29, 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/research/cultivating-the-bipartisan-consensus-on-india-in-the-116th-us-congress-58214/

[81] Stefania Benaglia, “EU-India – a Renewed Strategic Partnership or Business as usual?” CEPS, November 08, 2018, https://www.ceps.eu/eu-india-a-renewed-strategic-partnership-or-business-as-usual/

[82] EU Commission press release, “EU shapes its ambitious strategy on India,” European Commission, November 20, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_6481

[83] EEAS report, “Shared Vision, Common Action : A Stronger Europe, A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy,” European External Action Service, June 2016, http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/top_stories/pdf/eugs_review_web.pdf

[84] Idoia Villanueva Ruiz, “Statement on behalf of the GUE / NGL Group”, The European Parliament, January 29, 2020, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/CRE-9-2020-01-29-ITM-023_EN.html

[85] International Summit press release, “Joint Statement – 15th EU-India Summit, 15 July 2020,” The European Council, July 15, 2020, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/07/15/joint-statement-15th-eu-india-summit-15-july-2020/

[86] EU-India press release, “Joint Statement – 15th EU-India Summit,” The European Council, July 15, 2020, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/07/15/joint-statement-15th-eu-india-summit-15-july-2020/

[87] European Parliament report, “European Parliament Resolution on EU Political Relations with India,” European Parliament 014-2019 Resolutions, P8_TA(2017)0334, September 13, 2017, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2017-0334_EN.pdf

[88] Idoia Villanueva Ruiz, “Statement on behalf of the GUE / NGL Group”, The European Parliament, January 29, 2020, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/CRE-9-2020-01-29-ITM-023_EN.html

[89] Biden campaign, “Joe Biden’s Agenda For Muslim-American Communities”, Joe Biden-Kamala Harris presidential campaign 2020 — Official website, https://joebiden.com/muslimamerica/#

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV