-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

India will have to evolve new terms of engagement with its neighbours — terms that reflect the reality of our times

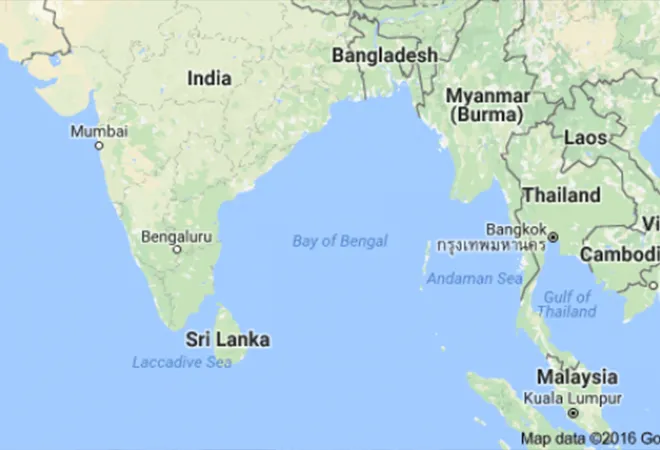

As Nepal gets ready to host the 4th Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) Summit on Thursday and Friday (August 30 and 31), this seven-nation regional grouping is hoping to get a new lease of life with a revival of Indian interest. The BIMSTEC was set up in 1997 and it now covers 1.6 billion people in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Thailand and Sri Lanka.

So far there is little to show in terms of substantive outcomes, but New Delhi has galvanised this organisation to set out a forward-looking agenda in the areas of regional connectivity, coastal shipping, space, energy, transport and tourism. The Narendra Modi government is keen to underscore BIMSTEC's centrality in its outreach to its neighbours and had invited members of this grouping to a BRICS outreach forum in Goa in 2016. New Delhi is planning to host war games involving BIMSTEC member states next month.

As one examines India's neighbourhood at the end of four years of the Modi government, a similar refrain has once again emerged —one that argues that India has lost the plot in its immediate vicinity.

In Sri Lanka, domestic political developments are turning against India and in the Maldives, India has found its diminishing clout being publicly flogged. A vocal critic of India has assumed power in Nepal with a massive political mandate and in the Seychelles, India is struggling to operationalise a pact to build a military facility. China's clout, meanwhile, is growing markedly around India's periphery, further constraining India's ability to push its regional agenda.

In many ways, there is nothing new in today's lament about India's declining regional clout. This lamentation is part of the Indian discourse and comes to the fore every few years with singular constancy.

Contrary to what many suggest, there was never a golden age of Indian predominance in South Asia and the wider Indian Ocean region. Smaller states in the region always had enough agency to chart their own foreign policy pathways — at times they converged with that of India and at times, they significantly diverged. There have always been 'extra regional' powers who came to the aid of India's neighbours, often to India's discomfiture.

After Independence, India has never encountered anything like China in its vicinity whose intent and capabilities pose the kind of challenge to Indian interests that New Delhi finds difficult to manage. China's entry into the South Asian region, while of concern to India, has opened up new avenues for India's smaller neighbours, which can be leveraged in dealings with New Delhi.

As a result, the very idea of what South Asian geography means is undergoing a change. Thus, it is not without reason that the idea of BIMSTEC has gained currency in India's policy-making circles. It can potentially allow India to break through the straightjacket of South Asia's traditional confines and leverage its Bay of Bengal identity to link up with the wider Southeast Asia. In that sense, it is about re-imagining India’s strategic geography altogether.

But the underlying factors that have traditionally framed India's difficulties in getting its neighbourhood policy right remain as potent as ever. India's structural dominance of South Asia makes it a natural target of resentment and suspicion, which New Delhi has found difficult to overcome. India is also part of the domestic politics of most regional states where anti-India sentiment is often used to bolster the nationalist credentials of various political formations.

State identity in South Asia often gets linked to oppositional politics vis-a-vis India. South Asian states remain politically fragile and as a result, the economic project in the region has failed to take off. This means that New Delhi's room to manoeuvre in the region is severely limited despite what many in New Delhi and outside would like to believe.

Successive Indian governments have struggled to get a grip on India's neighbourhood. Initially, the struggle with Pakistan sucked a large part of India's diplomatic capital. Today, there seems to be a clear recognition that India's Pakistan policy is merely a subset of India's China policy and as Beijing's economic and political engagement in India's periphery has grown, New Delhi is coming to terms with the reality of a ‘new’ South Asia.

India will not only have to more creatively re-imagine its strategic geography but also evolve new terms of engagement with its neighbours — terms which reflect the reality of our times in which both India and its neighbours can have a stake in each other’s success.

Revitalising BIMSTEC should, therefore, be a key priority of New Delhi.

This commentary originally appeared in Money Control.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Professor Harsh V. Pant is Vice President – Studies and Foreign Policy at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. He is a Professor of International Relations ...

Read More +