-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

edia coverage of the latest National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5) results from 2019 have broadly focused on the under-performance in nutrition, at the cost of examining disaggregated trends in child mortality. This article tries to examine new study findings of a stagnation in child mortality rates in India’s urban areas based on the Sample Registration System (SRS) data by Jean Dreze and colleagues in light of new NFHS-5 data from 17 states. The 2020 study had explored data from 20 bigger states and found evidence of a slowdown, pauses, and reversals in infant mortality in large parts of India in 2017 and 2018, the last two years for which SRS data on child mortality are available. NFHS-5 data offers an opportunity to examine if these trends persisted, or whether they have been reversed.

The most concerning aspect of the NFHS-5 fact sheets released from the 17 states was, indeed, regarding the state of India’s nutrition. Angus Deaton wrote in 2017 that while India aspires to be a global leader and change agent, more than one-third of her children are still “abnormally skinny and abnormally short”. The World Bank had earlier shared concerns that with 40% of India’s workforce having been stunted as children, the country is simply not going to be able to compete in the future economy. When the latest fact sheets from NFHS-5 were released in New Delhi last week, most of the public discussion revolved around nutrition indicators.

Analysis has shown than of the 17 states, 11 showed a worsening of stunting, including some of the populous states like Maharashtra, West Bengal, Gujarat, and Kerala. Other important nutrition indicators such as wasting and being underweight have shown stagnation or worsening in a majority of states where data is available. Indian experts remain extremely worried about the worsening of nutritional outcomes as such reversals generally coincide with economic distress. Any negative impact of COVID-19 on nutritional indicators will be over and above what is already seen in NFHS-5 results, which should concern policymakers.

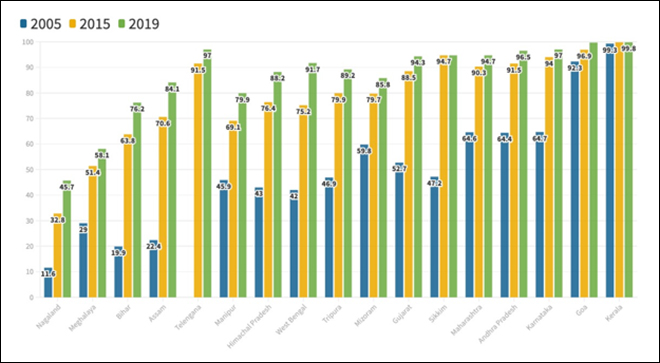

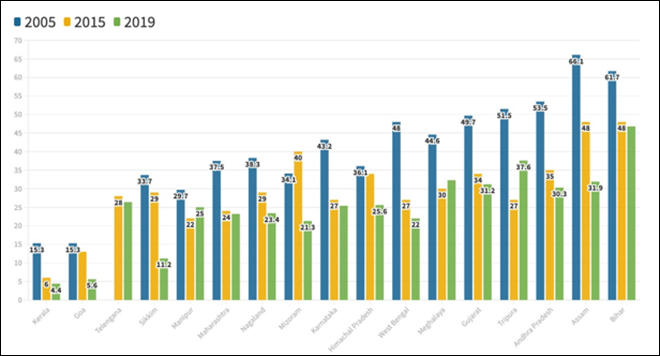

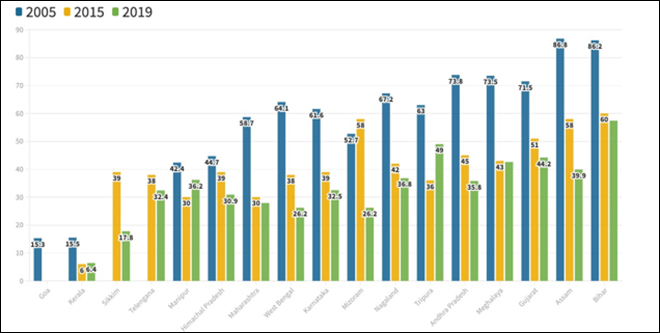

Figure 1: Proportion of Institutional Deliveries Across 17 States in India

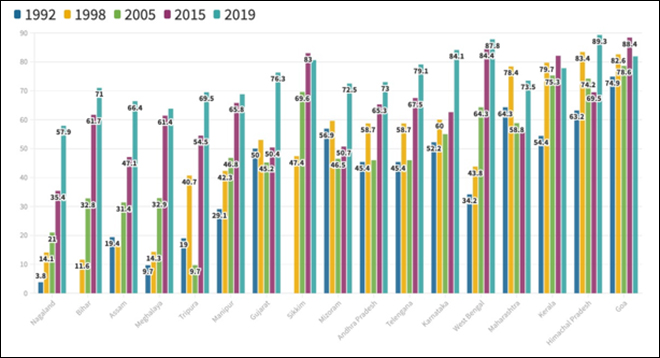

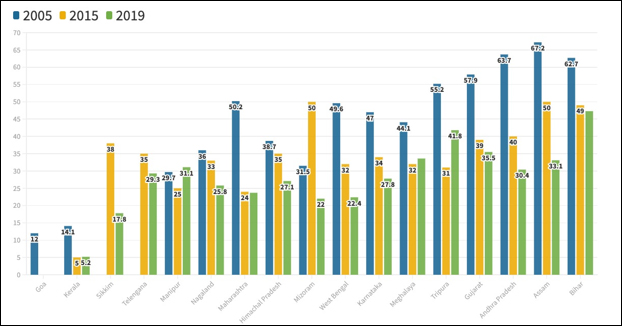

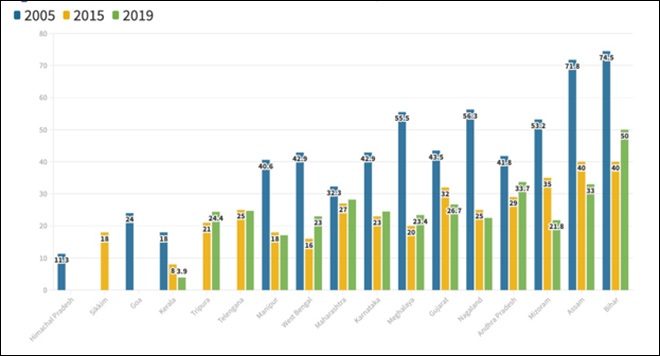

However, reports and initial analysis indicate that indicators of health outcomes and health service delivery have not been as bad, and have shown improvement in most states. The proportion of Institutional births out of total births (Figure 1), for example, has improved across all 17 states, barring Sikkim and Kerala, where it remained at 94.7% and 99.8% respectively, the same levels in 2015. In addition, most states with results known have also reached a replacement level of fertility, hopefully paving the way for a shift away from an obsession with population control at the level of political leadership as well as health policy. Vaccination levels of children (Figure 2), a key indicator given the immense challenge of COVID-19 vaccination for all that lies ahead, have also consistently increased across the states, barring Sikkim, Kerala and Goa—three states with already high levels of coverage.

Figure 2: Proportion of Fully Vaccinated Children aged 12-23 Months

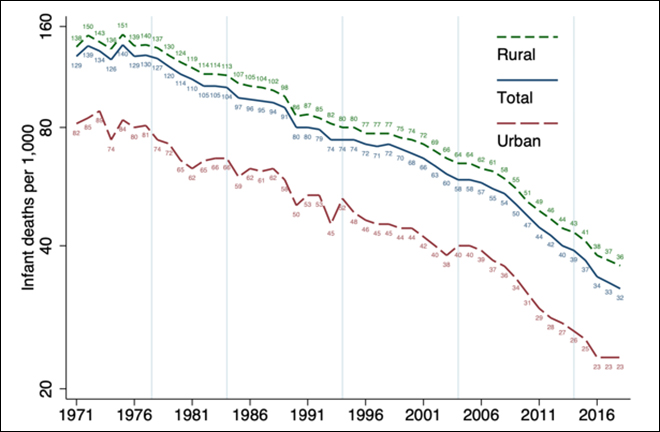

rends in India’s Infant Mortality Rate (IMR)—or number of deaths per 1000 live births—at state levels have been discussed in a recent study based on SRS data by Jean Dreze and colleagues, and a consistent decline of the overall IMR has been observed in the last two decades across the 20 states under study. The decline is consistent in rural IMR as well, as Figure 3 shows. However, the study found that in urban areas, IMR levels stagnated at 23 deaths per 1,000 births between 2016 and 2018. In addition, the overall IMR worsened in the poorer states of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh between 2016 and 2018, and urban IMR had worsened in a higher number of states. According to the study, this happened despite sustained improvements in household access to sanitation and clean fuel.

Figure 3: Infant Mortality Trends in India, 1971-2018

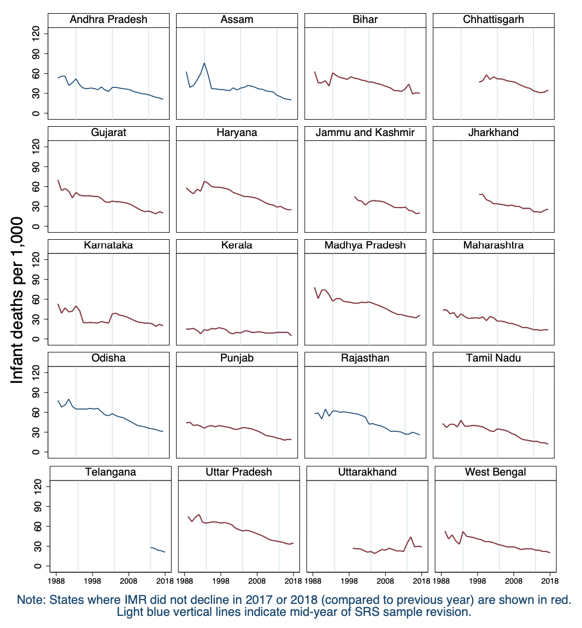

While at the national level there has been a stagnation in urban IMR, the state level analysis revealed an even more worrying picture in the study—11 out of 20 bigger states and 15 out of 20 urban populations within those states did not show improvements in IMR between 2016 and 2017 or 2017 and 2018 (Figure 4). The study observes that even though smaller samples cause higher variation in state-wise IMR trends in urban areas, trends in the last 15 years before 2016 had been relatively smooth. The study concluded that IMR declines slowed down, stagnated, or reversed in many parts of India, more so in urban areas. However, rural populations fared slightly better with 9 out of 20 bigger states showing stagnation in IMR. The study had hypothesised that the setbacks were at least partly attributable to the “startling experiment” of demonetisation in 2016.

Figure 4: Urban IMR by State, 1988 – 2018

In this context, the latest NFHS-5 State fact sheets give us an opportunity to see if there are indeed signs of stagnation of child mortality improvements across Indian states. Figure 5 compares IMR rates across the previous 3 NFHS rounds for the 17 Indian states for which 2019 data is available. Quite in contrast to the nutrition data, almost uniform improvement in IMR is observed across states other than Tripura, Manipur and Meghalaya. This is also in contrast to what the SRS data suggested, although big states like Maharashtra and Bihar reported only modest gains. Observing this trend, most of the media coverage around child mortality has been positive, focusing on the considerable improvement achieved by some states.

Figure 5: Trends in IMR Across 17 Indian States, 2005-2019

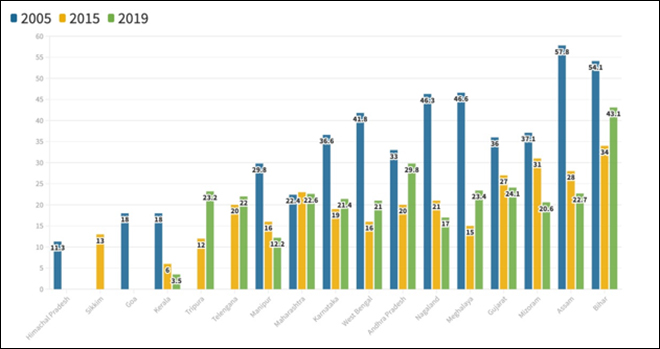

ural IMRs across the previous three NFHS rounds for the 17 Indian states for which 2019 data is available (Figure 6) follows almost the same trend. Barring the concerning performance of four states—Tripura showed a worsening from 31 in 2015 to 41.8 in 2019, Manipur showed a worsening from 25 in 2015 to 31.1 in 2019, Meghalaya showed a worsening from 32 in 2015 to 33.6 in 2019, and Kerala showed a worsening from 5 in 2015 to 5.2 in 2019—there is improvement across rural populations of all states. Rural populations of Andhra Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, West Bengal, Assam, Sikkim and Mizoram have shown impressive improvements in IMR over the last half decade. One would be tempted to conclude that the stagnations and reversals mentioned in the study by Jean Dreze and colleagues have been overcome.

Figure 6: Trends in Rural IMR Across 17 Indian States, 2005-2019

However, when data on urban IMR across these 17 states is analysed, it presented a completely different picture. A total of seven out of 17 states had their urban IMR worsen between 2015 and 2019. It is all the more concerning as these include bigger states like Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, Karnataka and Telangana, apart from Tripura and Meghalaya. Other than Mizoram, where urban IMR improved from 31 in 2015 to 20.6 in 2019, and Kerala, where urban IMR almost halved, the improvements across remaining states were relatively modest. These findings seem to reinforce what the SRS data and Dreze et al (2020) suggested: That the general adverse effects of poverty and unemployment as well as the sudden shock of demonetisation may have negatively impacted the urban population’s health status. The NFHS-5 data suggests that urban populations in particular may be paying the costs of a stagnant economy and the distress triggered by demonetisation, in the form of children’s lives.

Figure 7: Trends in Urban IMR Across 17 Indian States, 2005-2019

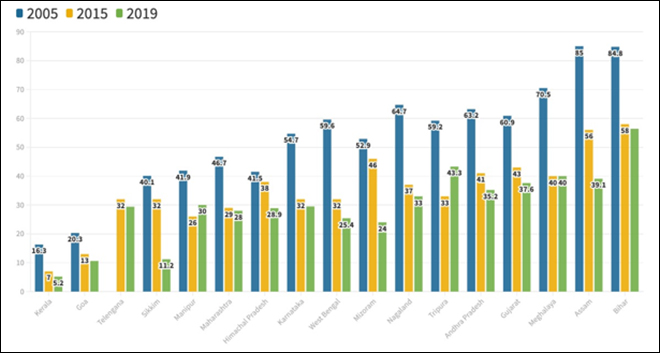

![]() o be doubly sure, inter-state comparisons of trends of under-five mortality rates (U5MR) were conducted, and the results were almost similar to the analysis of IMR. As Figure 8 shows, barring Tripura, Manipur and Meghalaya, all states report an overall improvement in U5MR.

o be doubly sure, inter-state comparisons of trends of under-five mortality rates (U5MR) were conducted, and the results were almost similar to the analysis of IMR. As Figure 8 shows, barring Tripura, Manipur and Meghalaya, all states report an overall improvement in U5MR.

Figure 8: Trends in U5MR Across 17 Indian States, 2005-2019

When it comes to rural IMR, the situation is almost the same as IMR and the overall U5MR trends. Tripura, Manipur and Kerala have shown a worsening of U5MR in 2019 when compared to 2015. In addition to Meghalaya, which showed near stagnation, large states like Bihar and Maharashtra showed very little improvement.

Figure 9: Trends in Rural U5MR Across 17 Indian States, 2005-2019

Comparison of trends in urban U5MR revealed similar findings as well. A total of seven out of 17 states had their urban IMR worsen between 2015 and 2019. Maharashtra joined the bigger states like Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, Karnataka and Telangana where U5MR worsened, apart from Tripura and Meghalaya. Other than Mizoram, where urban U5MR improved from 35 in 2015 to 21.8 in 2019, and Kerala, where urban U5MR halved from 8 to 3.9, the improvements across the remaining states were relatively modest.

Figure 10: Trends in Urban U5MR Across 17 Indian States, 2005-2019

While these findings are puzzling and counterintuitive given the long-term improvements in India’s child mortality rates over the past decades, these merit careful examination by demographic experts as well as policymakers, as two of India’s most reliable datasets—which we use for our Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) reporting—are saying the same thing. That child mortality rates in the urban areas of many Indian states have stagnated. As we know, IMR and U5MR are two very sensitive indicators of overall human health, and this needs immediate and focused response. COVID-19 may have made the challenge of improving the nutrition and health status of every Indian even more difficult, but hopefully, access to timely data will prove to be a handy tool in the fight.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Oommen C. Kurian is Senior Fellow and Head of Health Initiative at ORF. He studies Indias health sector reforms within the broad context of the ...

Read More +