The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) was enacted in 2016 to smoothen the process of resolution of insolvency. In 2015,

insolvency resolution in India took 4.3 years on an average – higher than that taken in the United Kingdom (1 year), the United States of America (1.5 years), South Africa (2 years) and Brazil (4 years). The delays were mainly attributed to the time taken to resolve cases in courts and a lack of well-defined bankruptcy framework.

Clarity in bankruptcy framework was expected to usher in a better business environment where the companies could be revived with relatively more ease. Resolution of bankruptcy in the IBC was clearly preferred over liquidation, which was posed as the last option.

Effective implementation of the IBC was expected to tackle the problem of bad loans on the financial creditors’ side on the one hand, and the problem of indebted companies on the other. This was supposed to be one of the crucial economic reforms that would enhance ease of doing business. IBC was also hailed as an important instrument to tackle the problem of non-performing assets (NPAs) in the banking sector.

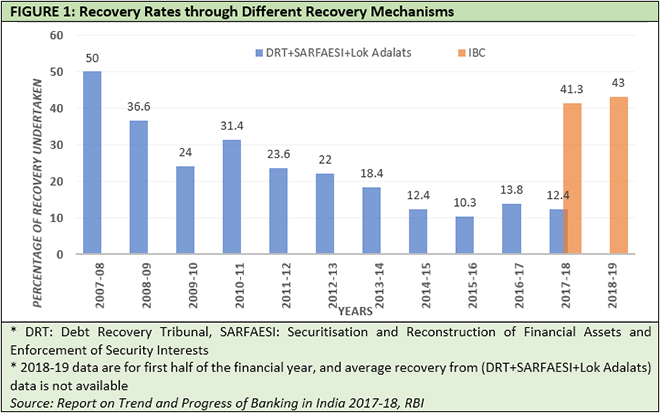

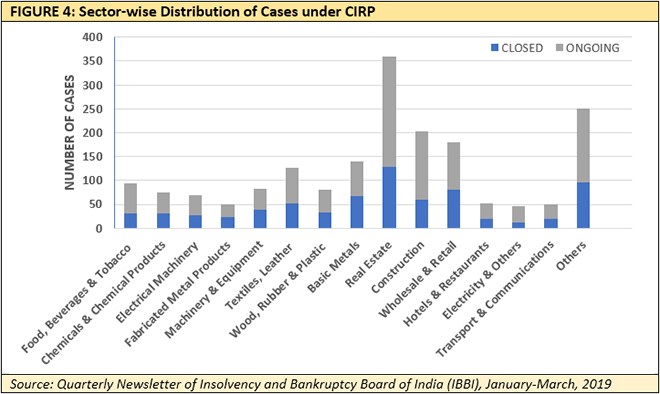

In the first two years of implementation, the average recovery rates of admitted insolvency cases through IBC indeed provides a sense of dynamism (

Figure 1). In the first half of 2018-19, recovery rate through IBC touched 43% – the highest since 2008-09.

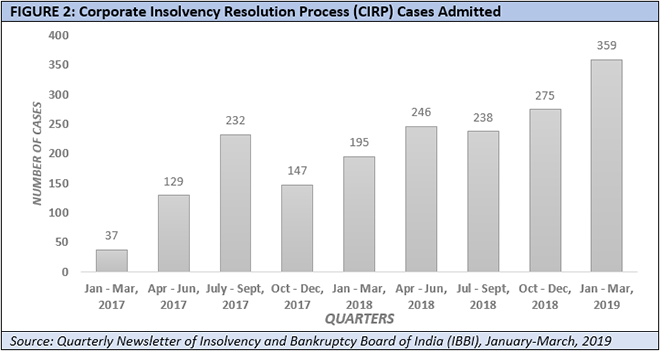

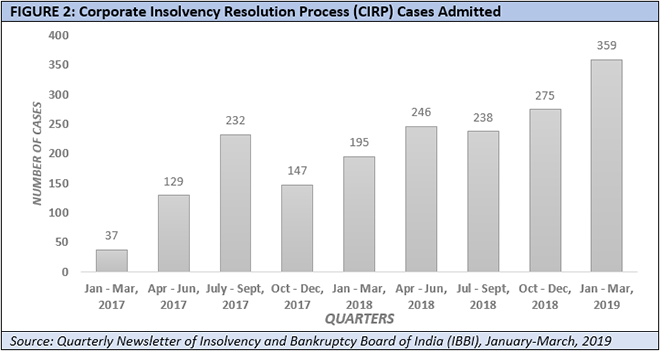

A steady increase in the number of admitted corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP) cases admitted provides more evidence of this dynamism (

Figure 2). By the end of March 2019, a total of 1858 cases were admitted for resolution – of which 152 have been appealed/reviewed/settled, 91 have been withdrawn, 378 ended in liquidation and 94 have ended in approval of resolution plans.

High number of liquidations is a cause for major worry as it violates IBC’s principal objective of resolving bankruptcy. Moreover, 1143 accumulated and unresolved cases red-flag the tendency to go back to the days of longer legal delays. If this delaying and accumulating trend persists then the purpose of enacting IBC is going to get defeated in near future.

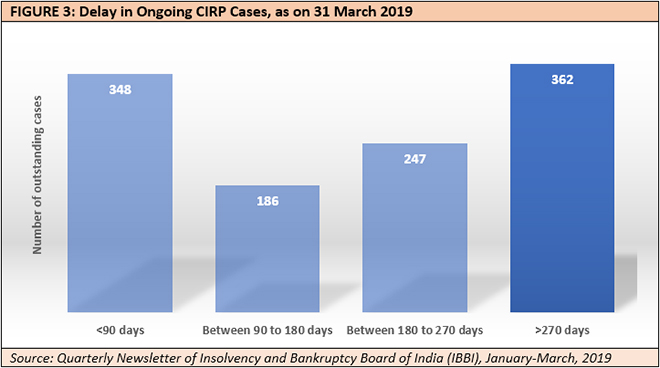

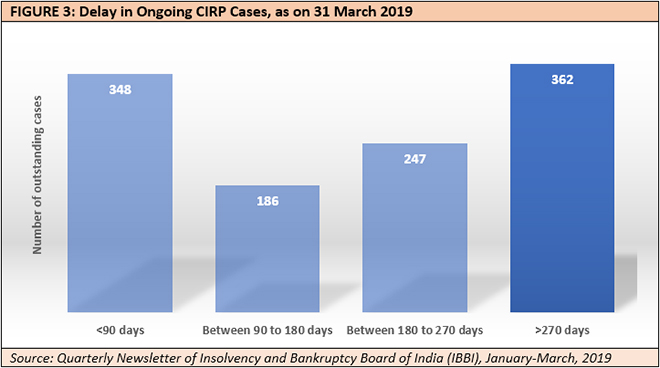

Figure 3

Figure 3 demonstrates the amount of delay in ongoing CIRP cases, as on 31 March 2019. It highlights the fact that a substantial number of cases have crossed the 180 days resolution limit, set in the original IBC 2016.

New

amendments to IBC, introduced and passed in both houses of the parliament this year, seek to correct this delaying tendency – among other things. New amendments stipulate that the resolution process must be completed within 180 days and can be extended up to 90 days if approved by the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT). Resolution process must be completed within 330 days, and if any case is pending over 330 days, then it must be resolved within next 90 days.

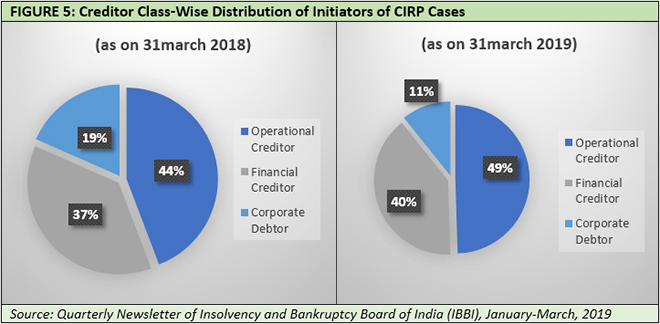

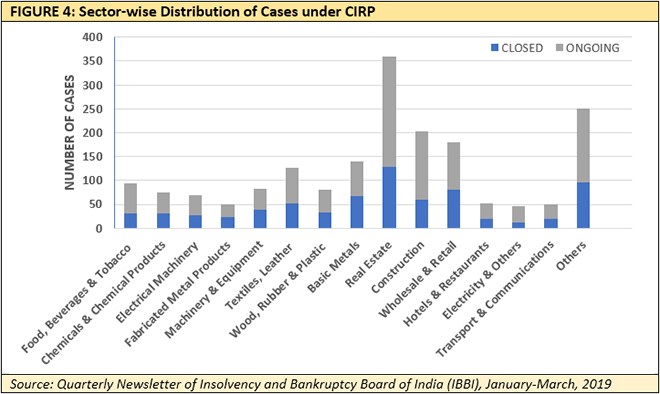

Sector-wise distribution of CIRP cases in

Figure 4 underlines the highest incidence of bankruptcies in the real estate sector. New amendments restored the home buyers’ status as financial creditors. It has been specified that when the debt is owned by a class of creditors beyond a specified number, financial creditors (in this case, home buyers) will be represented in the resolution process by an authorised representative in the committee of creditors (CoC). Such representative will vote on the basis of the decision taken by a majority of those creditors.

This is a welcome move, and should help quite a few homeowners in real estate projects which have gone bankrupt.

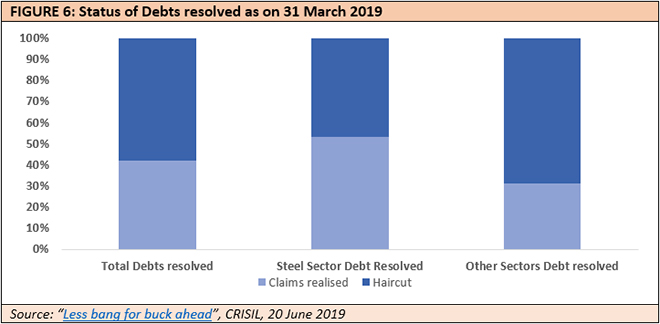

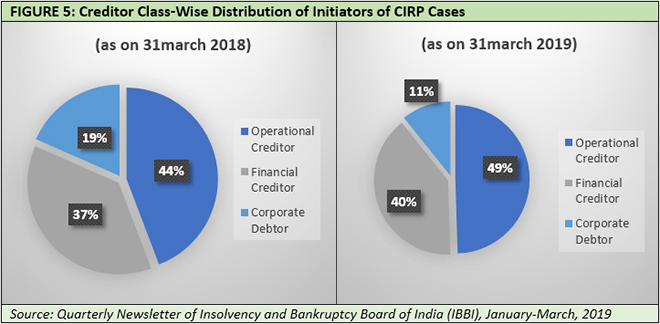

One of the major objectives of the IBC was to give pre-eminence to the financial creditors, so that the blockages in the credit channel of the economy get addressed. However,

Figure 5 shows that operational creditors initiated more resolution cases than financial creditors.

Original IBC stipulated that operational creditors receive an amount, not less than the amount they would receive in case of a liquidation. It has been amended and now operational creditors would get higher of – (i) the amount receivable under liquidation, and (ii) the amount receivable under resolution.

It seems to be beneficial for the operational creditors, but the repercussion of this amendment on the financial creditors remains to be observed in future. Financial creditors may lose out as a typical resolution process may fetch lower total amount recovered, after the haircut, compared to liquidation.

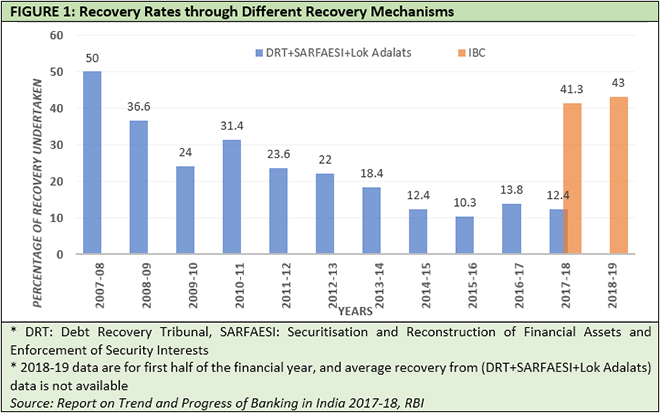

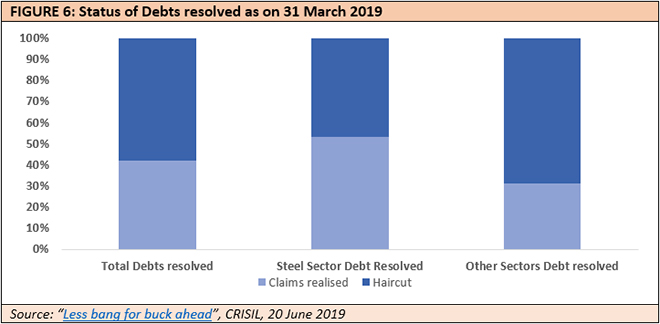

Looking at the trends, haircuts in the resolved debts is a teething problem, as can be seen in

Figure 6. Steel sector debts, in general, show a larger recovery percentage at 53%; for all other sectors the recovered debt ratio is at a much lower level of 31%.

If resolution of bad debt translates into big amount of haircuts then the trend is very alarming. Instead of easing credit supply to business, it may introduce a new barrier in the credit channel of the economy.

New amendments to IBC tried to address three issues. First, it strengthened provisions linked to time limits of the resolution process. This should have a positive impact. Second, it ensured minimum payouts to operational creditors – higher than the amount stipulated in the original IBC. This may have an adverse impact on the amount received by the financial creditors in future. If that happens, then some financial creditors, at least, may become wary of providing loans. Third, it specifies the modalities under which representative of a group of financial creditors (like home buyers) may vote in CoC. This is expected to be beneficial to specific classes of financial creditors like home buyers.

Operationalisation of IBC, till now, has been spoiled by myriad factors ranging from frivolous challenges posed by operational creditors and promoters to shortage of judges in tribunals. There has been allegation of “

gaming” the system as well. As a result, an important piece of legislation like IBC, which was expected to usher in a new era of ease of doing business, may fall into the trap of implementation failure.

Timely amendments, which provide more teeth to the Code, can only rescue the process. New amendments of 2019 in IBC should be closely watched and observed in that light.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) was enacted in 2016 to smoothen the process of resolution of insolvency. In 2015,

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) was enacted in 2016 to smoothen the process of resolution of insolvency. In 2015,  A steady increase in the number of admitted corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP) cases admitted provides more evidence of this dynamism (Figure 2). By the end of March 2019, a total of 1858 cases were admitted for resolution – of which 152 have been appealed/reviewed/settled, 91 have been withdrawn, 378 ended in liquidation and 94 have ended in approval of resolution plans.

High number of liquidations is a cause for major worry as it violates IBC’s principal objective of resolving bankruptcy. Moreover, 1143 accumulated and unresolved cases red-flag the tendency to go back to the days of longer legal delays. If this delaying and accumulating trend persists then the purpose of enacting IBC is going to get defeated in near future.

A steady increase in the number of admitted corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP) cases admitted provides more evidence of this dynamism (Figure 2). By the end of March 2019, a total of 1858 cases were admitted for resolution – of which 152 have been appealed/reviewed/settled, 91 have been withdrawn, 378 ended in liquidation and 94 have ended in approval of resolution plans.

High number of liquidations is a cause for major worry as it violates IBC’s principal objective of resolving bankruptcy. Moreover, 1143 accumulated and unresolved cases red-flag the tendency to go back to the days of longer legal delays. If this delaying and accumulating trend persists then the purpose of enacting IBC is going to get defeated in near future.

Figure 3 demonstrates the amount of delay in ongoing CIRP cases, as on 31 March 2019. It highlights the fact that a substantial number of cases have crossed the 180 days resolution limit, set in the original IBC 2016.

Figure 3 demonstrates the amount of delay in ongoing CIRP cases, as on 31 March 2019. It highlights the fact that a substantial number of cases have crossed the 180 days resolution limit, set in the original IBC 2016.

New

New  One of the major objectives of the IBC was to give pre-eminence to the financial creditors, so that the blockages in the credit channel of the economy get addressed. However, Figure 5 shows that operational creditors initiated more resolution cases than financial creditors.

One of the major objectives of the IBC was to give pre-eminence to the financial creditors, so that the blockages in the credit channel of the economy get addressed. However, Figure 5 shows that operational creditors initiated more resolution cases than financial creditors.

Original IBC stipulated that operational creditors receive an amount, not less than the amount they would receive in case of a liquidation. It has been amended and now operational creditors would get higher of – (i) the amount receivable under liquidation, and (ii) the amount receivable under resolution.

It seems to be beneficial for the operational creditors, but the repercussion of this amendment on the financial creditors remains to be observed in future. Financial creditors may lose out as a typical resolution process may fetch lower total amount recovered, after the haircut, compared to liquidation.

Looking at the trends, haircuts in the resolved debts is a teething problem, as can be seen in Figure 6. Steel sector debts, in general, show a larger recovery percentage at 53%; for all other sectors the recovered debt ratio is at a much lower level of 31%.

Original IBC stipulated that operational creditors receive an amount, not less than the amount they would receive in case of a liquidation. It has been amended and now operational creditors would get higher of – (i) the amount receivable under liquidation, and (ii) the amount receivable under resolution.

It seems to be beneficial for the operational creditors, but the repercussion of this amendment on the financial creditors remains to be observed in future. Financial creditors may lose out as a typical resolution process may fetch lower total amount recovered, after the haircut, compared to liquidation.

Looking at the trends, haircuts in the resolved debts is a teething problem, as can be seen in Figure 6. Steel sector debts, in general, show a larger recovery percentage at 53%; for all other sectors the recovered debt ratio is at a much lower level of 31%.

If resolution of bad debt translates into big amount of haircuts then the trend is very alarming. Instead of easing credit supply to business, it may introduce a new barrier in the credit channel of the economy.

New amendments to IBC tried to address three issues. First, it strengthened provisions linked to time limits of the resolution process. This should have a positive impact. Second, it ensured minimum payouts to operational creditors – higher than the amount stipulated in the original IBC. This may have an adverse impact on the amount received by the financial creditors in future. If that happens, then some financial creditors, at least, may become wary of providing loans. Third, it specifies the modalities under which representative of a group of financial creditors (like home buyers) may vote in CoC. This is expected to be beneficial to specific classes of financial creditors like home buyers.

Operationalisation of IBC, till now, has been spoiled by myriad factors ranging from frivolous challenges posed by operational creditors and promoters to shortage of judges in tribunals. There has been allegation of “

If resolution of bad debt translates into big amount of haircuts then the trend is very alarming. Instead of easing credit supply to business, it may introduce a new barrier in the credit channel of the economy.

New amendments to IBC tried to address three issues. First, it strengthened provisions linked to time limits of the resolution process. This should have a positive impact. Second, it ensured minimum payouts to operational creditors – higher than the amount stipulated in the original IBC. This may have an adverse impact on the amount received by the financial creditors in future. If that happens, then some financial creditors, at least, may become wary of providing loans. Third, it specifies the modalities under which representative of a group of financial creditors (like home buyers) may vote in CoC. This is expected to be beneficial to specific classes of financial creditors like home buyers.

Operationalisation of IBC, till now, has been spoiled by myriad factors ranging from frivolous challenges posed by operational creditors and promoters to shortage of judges in tribunals. There has been allegation of “ PREV

PREV