Minister of State for Home Kiren Rijiju has opened up a Pandora's Box by raising the issue of granting citizenship to Chakmas and Hajongs living in Arunachal Pradesh for over 50 years. Chairing a review meeting of the security situation in the Northeast on 16 May, Rajnath Singh, the Union Home Minister, urged for active cooperation from the concerned State Government to deal with the issue of citizenship to Chakmas and Hajongs. Consequently, the Centre has decided to grant conditional citizenship to these stateless communities.

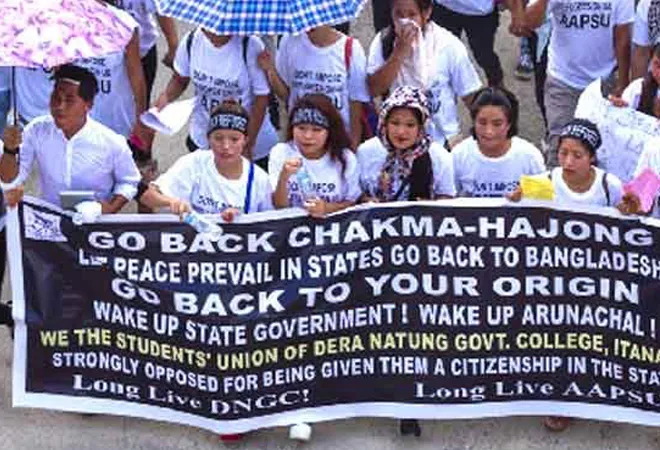

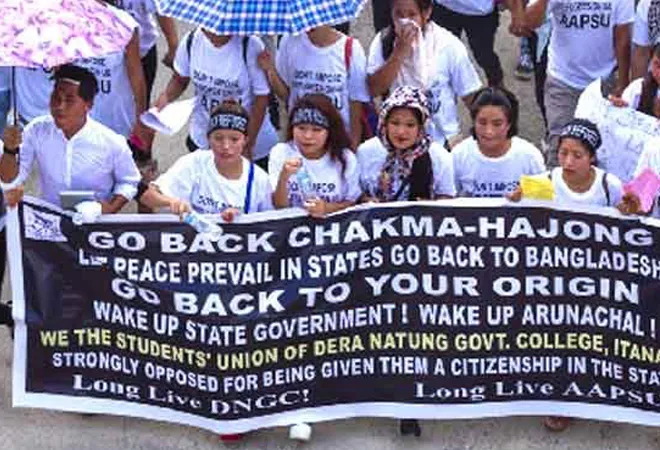

Though consultations are on with the State Government, the citizenship will not entitle the aforesaid communities to rights enjoyed by the Scheduled Tribes in the state, including land ownership, according to the officials of the Union Home Ministry. Indeed, the State Government has not taken up this proposal of issuing citizenship wholeheartedly. Rather, the State Government has apprehended that if citizenship is granted to them, it would reduce the indigenous tribal communities to a minority and deprive them of opportunities. It may be recalled here that since 1990, the All Arunachal Pradesh Students’ Union (AAPSU) has raised its voice against issuing citizenship to these stateless communities. Presently, Arunachal Pradesh Congress Committee (APCC) has extended its support to AAPSU in the democratic movement and has demanded voluntary resignation of Kiren Rijiju over the recent development on the issue. APCC has further argued that 'if Chakmas and Hajongs are allowed to have Arunachalee status, it will not only invite demographic change but also will breeds socio-economic and political threat in near future.' Against the backdrop of this political tussle, what will be the fate of nearly 100,000 Chakmas and Hajongs living in Arunachal Pradesh?

Chakmas, Hajongs and their statelessness

According to the International Law Commission, the definition of stateless persons contained in Article 1 (1) of the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, statelessness is the quality of being, in some way, without a state. In fact, it means without a nationality, or at least without the protection that nationality should offer. Nationality is the legal bond between a state and an individual. It is a bond of membership that is acquired or lost, according to rules set by the state. Though Chakmas and Hajongs were encouraged by the Indian Government to come and settle in the desolate land of NEFA (North East Frontier Agency, now Arunachal Pradesh) as refugees when they were displaced from the Chittagong Hill Tracts of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) due to the building of the Kaptai Dam over the river Karnaphuli in 1964, the Indian Government has not yet granted them citizenship. They are neither the citizens of Bangladesh nor India, which has made them

de jure stateless.

Photo: Kazu Ahmed/Flickr

Photo: Kazu Ahmed/Flickr

The government records of Arunachal Pradesh indicate that between 1964 and 1969, a total of 2,748 families of Chakmas and Hajongs comprising nearly 14,888 persons were sent to NEFA. Initially, these refugees were settled in 10,799 acres of land in the three districts, namely, Lohit, Subansiri and Tirup (now in Changlang). By 1979, these figures increased up to 3919 families consisting of 21,494 persons. According to the 1991 census report, total number of the evacuees from the CHT increased further to around 65,000. Due to absence of census survey since then, the aforesaid figure is quoted in all accounts of the issue. But now it is said in public discourse that this number has been increased up to 100,000.

Initially, the plots of land varying from 5 to 10 acres per family (including 3 to 5 acres of cultivable land) depending upon the size of the family was allotted to these refugees under a centrally sponsored rehabilitation scheme of India. A cash grant for each family was also sanctioned by the Ministry of Rehabilitation. Later, under the Indira-Mujib Agreement of 1972, it was decided that India and not Bangladesh would be responsible for all migrants who entered India before 25 March 1971 and therefore the Chakmas and Hajongs, who came to India before the aforesaid date, would be considered for the grant of Indian citizenship. However, though these "new migrants" got refugee cards after crossing the international border, the Government of India provided citizenship to only a microscopic minority (1,530 in numbers as of 2010) out of 100,000. As majority of these Chakmas and Hajongs do not have nationality, they are systematically deprived of other fundamental rights.

Legal battle for citizenship

Due to increasing incidents of social discrimination and economic boycott against the Chakmas and Hajongs since early 1990s, the Committee of Citizenship Rights for the Chakmas of Arunachal Pradesh (CCRCAP) was formed to raise their demand for citizenship rights. Since its inception, the CCRCAP repeatedly informed National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) about the threat to their lives and properties. Though initially the NHRC treated it as a formal complaint, on 7 December 1994, it directed the Arunachal and Central Governments to provide information about the steps taken to protect the Chakmas and Hajongs. The issue became critical following the resolution passed by the political leaders of Arunachal Pradesh, led by then Chief Minister Gegong Apang, to resign

en masse from the national party membership if the Chakmas and Hajongs are not deported by 31 December 1995. The resolution also prohibited any social interactions between the local Arunachalees and the Chakmas-Hajongs.

The CCRCAP approached the NHRC again to seek protection of their lives and liberty in view of the deadline and support extended to the strongest students' organisation AAPSU (All Arunachal Pradesh Students Union) by the State Government. As the State Government was inordinately delaying to inform on the steps taken to protect the Chakmas and Hajongs, the NHRC, headed by Justice Ranganath Mishra, approached the Supreme Court to seek appropriate relief, filing a writ petition (No. 720/1995). The apex court in its interim order on November 2, 1995 directed the State Government to "ensure that the Chakmas situated in its territory are not ousted by any coercive action, not in accordance with law." As the 31 December 1995 deadline approached, the then Prime Minister P.V. Narashima Rao formed a high-level committee, headed by then Home Minister S.B. Chavan. On 9 January 1996, the Supreme Court gave its judgment in the case of NHRC vs. State of Arunachal Pradesh.

Post-verdict situation

The situation slightly changed after the Supreme Court verdict in 1996. A Committee under the Chairmanship of Joint Secretary (Northeast), Ministry of Home Affairs had been constituted to examine various issues relating to settlement of the Chakmas and Hajongs in Arunachal Pradesh, including the possibility of grant of citizenship to eligible persons and to recommend measures to be taken by the Central Government/State Government in this matter. The Committee decided to organise a four-party talk among the representatives of AAPSU, CCRCAP, the Central Government and the State Government on this issue, keeping the fact in mind that dialogue among them can only help to listen to each other and in the long run it may be helpful to fill the gap between the Chakmas and the other major indigenous tribal groups like Khamti, Singphoo, Adi, Nishi of Arunachal Pradesh.

In September 2015, the Supreme Court gave a deadline to the Centre to confer citizenship to these refugees within three months. As a followup, consultations started between the State and the Centre on this issue. It is to be recalled in this context that in its election manifesto for the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP had declared India as "a natural home for persecuted Hindus." After coming to power at the Centre, the BJP led NDA government has taken several steps to simplify the process for granting long-term visa and citizenship to those who have taken shelter in India from neighbouring countries. Under this circumstances introduction of the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016 is a worth-mentioning step. Moreover, BJP's gain as a ruling party at Arunachal Pradesh after many years of Congress rule paves the way to look into the issue of granting citizenship to the Chakmas and Hanjongs in a different way.

Colonial history coupled with the post-colonial transition and role of identity politics has made the situation more complicated, as a consequence of which a large number of the Chakmas and Hajongs living in the designated areas of Diyun and Bordumsa in Changlang, Chowkham in Lohit and Kokila areas of Papumpare districts have become stateless. Will these people be able to get recognition as citizens of India ultimately after staying there since 1964 in spite of the strong opposition of AAPSU and APCC? The question still haunts many Chakmas and Hajongs, who being displaced from their own adobe, have no place to return.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Minister of State for Home Kiren Rijiju has opened up a Pandora's Box by raising the issue of granting citizenship to Chakmas and Hajongs living in Arunachal Pradesh for over 50 years. Chairing a review meeting of the security situation in the Northeast on 16 May, Rajnath Singh, the Union Home Minister, urged for active cooperation from the concerned State Government to deal with the issue of citizenship to Chakmas and Hajongs. Consequently, the Centre has decided to grant conditional citizenship to these stateless communities.

Though consultations are on with the State Government, the citizenship will not entitle the aforesaid communities to rights enjoyed by the Scheduled Tribes in the state, including land ownership, according to the officials of the Union Home Ministry. Indeed, the State Government has not taken up this proposal of issuing citizenship wholeheartedly. Rather, the State Government has apprehended that if citizenship is granted to them, it would reduce the indigenous tribal communities to a minority and deprive them of opportunities. It may be recalled here that since 1990, the All Arunachal Pradesh Students’ Union (AAPSU) has raised its voice against issuing citizenship to these stateless communities. Presently, Arunachal Pradesh Congress Committee (APCC) has extended its support to AAPSU in the democratic movement and has demanded voluntary resignation of Kiren Rijiju over the recent development on the issue. APCC has further argued that 'if Chakmas and Hajongs are allowed to have Arunachalee status, it will not only invite demographic change but also will breeds socio-economic and political threat in near future.' Against the backdrop of this political tussle, what will be the fate of nearly 100,000 Chakmas and Hajongs living in Arunachal Pradesh?

Minister of State for Home Kiren Rijiju has opened up a Pandora's Box by raising the issue of granting citizenship to Chakmas and Hajongs living in Arunachal Pradesh for over 50 years. Chairing a review meeting of the security situation in the Northeast on 16 May, Rajnath Singh, the Union Home Minister, urged for active cooperation from the concerned State Government to deal with the issue of citizenship to Chakmas and Hajongs. Consequently, the Centre has decided to grant conditional citizenship to these stateless communities.

Though consultations are on with the State Government, the citizenship will not entitle the aforesaid communities to rights enjoyed by the Scheduled Tribes in the state, including land ownership, according to the officials of the Union Home Ministry. Indeed, the State Government has not taken up this proposal of issuing citizenship wholeheartedly. Rather, the State Government has apprehended that if citizenship is granted to them, it would reduce the indigenous tribal communities to a minority and deprive them of opportunities. It may be recalled here that since 1990, the All Arunachal Pradesh Students’ Union (AAPSU) has raised its voice against issuing citizenship to these stateless communities. Presently, Arunachal Pradesh Congress Committee (APCC) has extended its support to AAPSU in the democratic movement and has demanded voluntary resignation of Kiren Rijiju over the recent development on the issue. APCC has further argued that 'if Chakmas and Hajongs are allowed to have Arunachalee status, it will not only invite demographic change but also will breeds socio-economic and political threat in near future.' Against the backdrop of this political tussle, what will be the fate of nearly 100,000 Chakmas and Hajongs living in Arunachal Pradesh?

Photo: Kazu Ahmed/Flickr

Photo: Kazu Ahmed/Flickr PREV

PREV