The Government does not seem to be in any hurry to solve the deep economic problems confronting the Indian economy. Many experts have come and gone pronouncing antidotes to the slow down but still there is absence of a focused policy at the Centre which could have included opinions of the pundits. The Government has so far failed to come up with a concrete action plan to deal with the slowdown.

It is a very difficult situation that India is faced with regarding demand. All these years, it was consumer demand which was the engine of growth for the Indian economy. Suddenly, over the last one year, we find it is no longer so and instead it is the Government expenditure which is keeping the economy going.

Why did consumers who are by no means committed to austerity suddenly hold back purchases? Even after hefty discounts during the last festival season,

sales did not pick up. It has to do with the fear of what the future holds. When the economy is booming and there is low unemployment, there is a rise in consumer confidence and people are happy to spend on themselves and their families.

The

consumer confidence surveys have shown a dip in confidence which is why people are not willing to spend. They are afraid of job losses and hard times ahead. Many are being forced to dip into their savings in order to maintain their living standards. Many have dependent parents and unemployed family members to support. They are worried about rising private school fees and tuition costs for their children. People are worried about the high costs of treatment in case of serious illness. People are afraid that if in the future, income flows dry up, they will not be able to maintain their living standards and hence hold back on buying a new car or washing machine. There is also a lurking fear of inflation because vegetable prices have been soaring recently.

Food inflation rose to 10 percent and retail inflation to 5.54 percent in November.

The other side of the coin are the investors who are holding back on investments because they have already a problem of inventory pile up due to slow sales and if they do not see prospects of demand for their goods rising, they will hold back on expansion of production.

It is low investment, low income and low demand that are dominating features of the economic scene. People need incomes. If there was high growth in the manufacturing sector, there could have been more people finding jobs in factories. Unlike the IT sector, the manufacturing sector is open to all kinds of unskilled and skilled labour. Unfortunately, the sector has been floundering and there has been a shrinkage in output (3.8 percent) in October and November 2019. It clearly indicates that the sector is not the lead sector anymore.

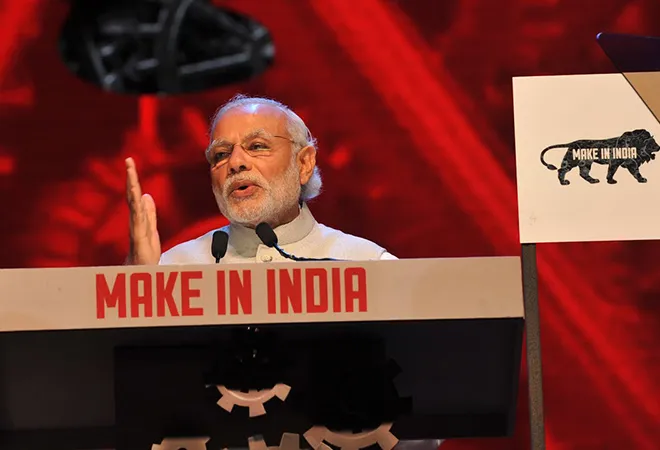

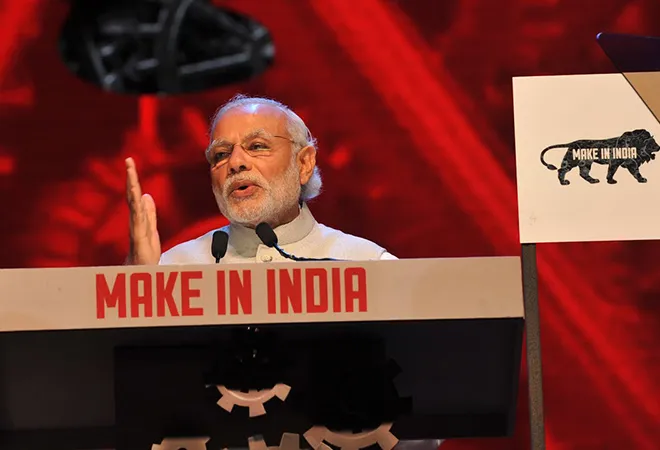

The ‘Make in India’ initiative did not take off as expected and that is the main reason why the manufacturing sector has remained stagnant. It promised foreign manufacturing units financial incentives, less red tape, Intellectual property rights protection and the availability of a young work force, low wages and a huge domestic market. Many big names like Apple, Xiaomi have increased their production in India and Samsung has the world’s largest smart phone plant near New Delhi even though the parts are made outside India. In 2015, India had the largest volume of announced Greenfield investment (‘greenfield investment’ is defined as tangible investments resulting in new or expanded facilities and jobs and include manufacturing) at $60 billion according to Financial Times (London) Data services. In 2018, China got $107 billion and India got $55 billion. FDI into manufacturing has been only $8 billion during the FY 19 till March.

The

fall in the flow of FDI to the manufacturing sector from its previous highs could be a reason why

‘Make in India’ initiative has not taken off. This is surprising because India’s ranking according to World Bank’s ‘Ease of Doing Business’ has gone up to 63

rd place over the last few years. The question now arises that why is it so that the manufacturing did not take off in India to the same extent, as it has in Vietnam and Bangladesh? One of the main reasons is infrastructure like roads, power supply and slow reforms in land acquisition and labour laws. Our neighbours also have much lower wages and their productivity is higher in garments trade. India who once boasted to be the most favoured FDI destination no longer remains so. What with more political problems and protests coming daily to the fore. It will put off many foreign investors.

Also the share of manufactures in GDP has remained around 15 percent rather than anywhere near the targeted 25 percent and India is missing out in being a part of the global value supply chain.

The government has started giving cash to the poor in the rural areas but that may not lead to any significant rise in demand. It is also a paltry sum of Rs 6000 a year which may be enough to take care of personal loans. The incomes of the rural population have to rise by creation of non-farm jobs but this is not happening. Had the Make in India initiative taken off, there would have been many food processing, jams and pickles making factories as well as light manufacturing units in rural areas, giving employment to both men and women. The various other rural initiatives which were undertaken to increase employment also don’t seem to have been very successful. Rural India is marked by stagnant wages and low farmers’ incomes. Food inflation may however help in raising income and demand.

When the economy starts growing faster, people would become more optimistic about their own job security and incomes and would start spending. Manufacturing growth holds the key to achieving higher GDP growth.

Finance Minister Nirmala Seetharaman may give incentives to average consumers by cutting IT rates in the next Budget. It may or may not help. The corporate tax cut has not yet unleashed the ‘animal spirits’ among entrepreneurs. There is not been a great change in investment pattern since the corporate tax cut.

The manufacturing sector should be revamped and productivity of workers should rise through efficient infrastructure. The government’s increase in expenditure on infrastructure will help in a big way. Raising government expenditure at times like this is not unwarranted even though the fiscal deficit target may remain unmet.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The Government does not seem to be in any hurry to solve the deep economic problems confronting the Indian economy. Many experts have come and gone pronouncing antidotes to the slow down but still there is absence of a focused policy at the Centre which could have included opinions of the pundits. The Government has so far failed to come up with a concrete action plan to deal with the slowdown.

It is a very difficult situation that India is faced with regarding demand. All these years, it was consumer demand which was the engine of growth for the Indian economy. Suddenly, over the last one year, we find it is no longer so and instead it is the Government expenditure which is keeping the economy going.

Why did consumers who are by no means committed to austerity suddenly hold back purchases? Even after hefty discounts during the last festival season,

The Government does not seem to be in any hurry to solve the deep economic problems confronting the Indian economy. Many experts have come and gone pronouncing antidotes to the slow down but still there is absence of a focused policy at the Centre which could have included opinions of the pundits. The Government has so far failed to come up with a concrete action plan to deal with the slowdown.

It is a very difficult situation that India is faced with regarding demand. All these years, it was consumer demand which was the engine of growth for the Indian economy. Suddenly, over the last one year, we find it is no longer so and instead it is the Government expenditure which is keeping the economy going.

Why did consumers who are by no means committed to austerity suddenly hold back purchases? Even after hefty discounts during the last festival season,  PREV

PREV