-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Himachal Pradesh’s health and nutrition challenges are compounded by severe human resource constraints in the public sector. The earlier gains of the state are at the risk of being wiped out.

Himachal Pradesh has been India’s quintessential rural health success story. At 90 percent, it has the highest proportion of rural population among Indian states. At the same time, when compared to other states with similar rural populations, Himachal has, on the average, better human development indicators. It has been among India’s best states in terms of HDI along with Kerala and Delhi, and despite its high rural population, achieved replacement level of Total Fertility Rate, quite early on. Only Kerala, Jammu and Kashmir, Delhi and Punjab have a higher life expectancy at birth than Himachal among the bigger states of India. It is a comparatively richer state, with a GSDP per capita similar to Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. The State Commission of Health, constituted in 2014 with prominent experts as members, focused on developing inter-sectoral strategies required to address environmental, nutritional and social determinants of health as a part of the overall development of the state, among other things.

Himachal Pradesh also happens to be the home state of the Union Health Minister, Mr. Jagat Prakash Nadda, who was earlier the state health minister. Himachal is the state with the highest government health spending per capita in India, and the focus on public spending has made the state the second lowest in the country in terms of percentage out of pocket health expenditure. Himachal Pradesh can be put in direct contrast with Kerala, a state with which it competes for the top slot in terms of best human development in the country. Kerala spends only half of what Himachal spends in terms of public expenditure on health per capita, and has the highest percentage out of pocket health expenditure in the country.

While household reporting catastrophic health expenditure in Kerala is 20.4%, the highest in the country, it is 13.1% in Himachal, near the all India average. The percentage of private sector inpatient cases is 22.9% in the state, among the lowest in the country. Kerala on the other hand has 66.1% inpatient load treated by the private sector. This almost exclusive policy focus on the public sector makes Himachal unique among the relatively richer states of India, who on the average are identifiable by a dominant private sector.

While household reporting catastrophic health expenditure in Kerala is 20.4%, the highest in the country, it is 13.1% in Himachal, near the all India average.

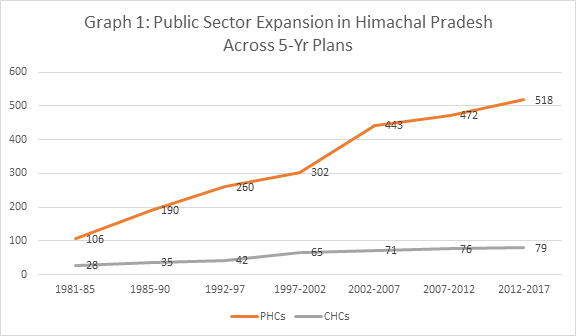

Himachal is one among a few Indian states where as per population norms, there is no shortfall of Sub Centres, PHCs or CHCs. The state was formed in 1971 by combining parts of Punjab and the erstwhile Union Territory. From the beginning, the state went for rapid expansion of its public primary health care infrastructure as shown in Graph 1. During the same period, Himachal also managed to increase the number of Sub Centres from 1299 to 2071. Himachal, with just .57% of India’s population, has more sub-divisional hospitals than Bihar — a state with 8.58% of India’s total population.

Source: NHRM

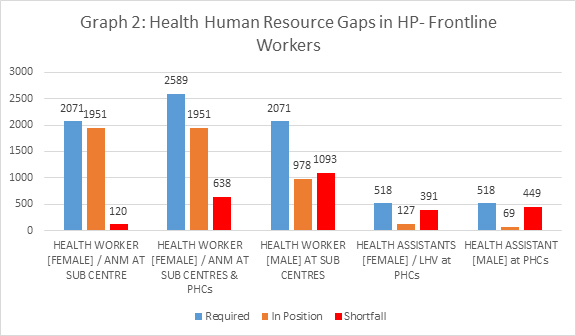

However, despite such strong performance on the physical infrastructure front, Himachal health system is reeling under severe staff shortages. Graph 2 shows the current shortfall across the frontline health workers for Himachal. Female health worker/ANMs in Primary Health Centres are virtually zero, and male health workers at Sub Centres have a shortfall of more than 50%. Out of the total 1951 sub centres functioning in the state, 214 work without a female health worker/ANM, 1,129 work without a male health worker, and 121 work without both.

Source: HMIS

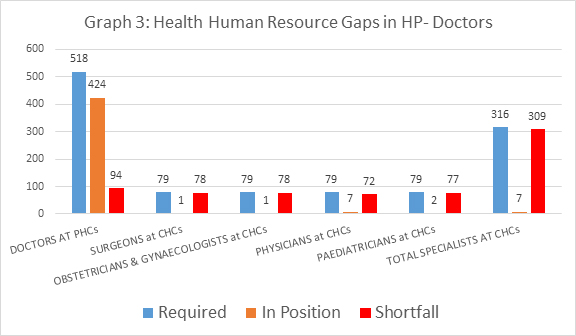

As Graph 3 shows, the shortage of doctors is acute in the public sector hospitals in the state, particularly specialists. Around 20% of Himachal’s PHCs function without an allopathic doctor. Only 95 PHCs have a female doctor. Alternative medicine is not filling up the void either — out of 518 functioning PHCs in the state, only 44 have AYUSH facility. The shortage of specialists (surgeons, OB&GY, physicians & paediatricians) are at an alarming level: out of a required number of 316 specialist doctors, only seven are in position in the state. The doctors at PHCs and the General Duty Medical Officers (GDMOs) in the CHCs (220 of a required 234 in position) are the mainstay of the state’s health system, handling most of the disease burden.

Source: NHRM

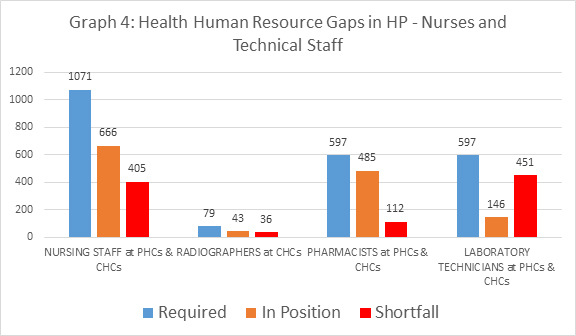

As Graph 4 shows, the shortage of nursing staff as well as the lack of allied health workers render a significant proportion of the state’s public sector healthcare delivery system ineffective. A considerable number of PHCs and CHCs work without nurses, radiographers, pharmacists, or lab technicians.

Source: HMIS

Given the relatively smaller footprint of the private sector in the state, such severe staff shortages — despite a high per capita public health spending by the state — can have disastrous implications on the health of the citizens. Given these gaps like 98% of shortfall in specialists, it is puzzling that in FY 2014-15, expenditure on human resources constituted only seven percent in the overall NRHM expenditure in the state — the lowest in the country.

Himachal's expenditure in human resources in 2014-15 constituted only seven percent of the overall NRHM expenditure — the lowest in the country.

The latest information on Himachal’s health and nutrition indicators are available from the NFHS-4 survey, fieldwork for which was conducted in 2016. The survey gathered information from 9,225 households, 9,929 women, and 2,185 men. According to the survey, the sex ratio of the state improved from 1070 in 2005-06 to 1078 in 2016. Himachal also has managed to have all its households access to electricity. Proportion of households with improved sanitation facility doubled over the last decade – from 37.2% to 70.7%. Health insurance coverage has improved by five times over the last decade — as well to 25.8% of households with at least one member covered by a health scheme or health insurance.

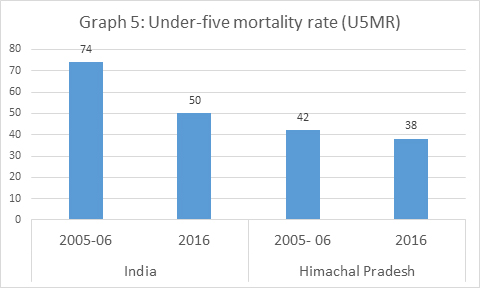

However, both infant mortality as well as under-five mortality reductions in the last decade have been slow. Graph 5 and 6 show that even when compared to the improvements in the country averages, the state’s success was rather limited.

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

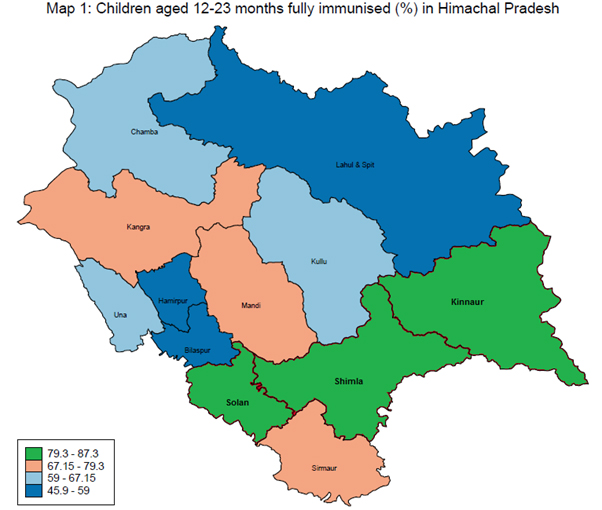

While the indicators of maternal health and delivery care have shown considerable improvement, the proportion of children aged 12 to 23 months who have been fully immunised has in fact gone down, from 74.25% in 2005-06 to 69.5% in 2016, which is a matter of major concern. The district level exploration of immunisation achievement, tried in Map 1, gives a picture of stark district level disparities. Hamirpur has the lowest immunisation coverage at 45.9% while Shimla has the highest at 87.3%. Bilaspur, Lahul and Spiti as well as Una districts have lower than 60% coverage of full immunisation.

Source: NFHS

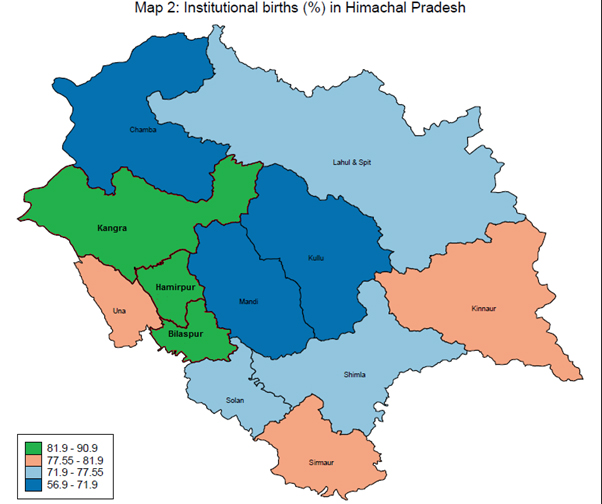

The proportion of institutional births has almost doubled over the last decade — from 43.1% to 76.4%. However, the overall achievement still remains lower than the India average, and there are considerable district level differences as explored in Map 2. Hamirpur happens to be the best performer with 90.9% institutional births, and the Chamba district is the lowest performer with only 56.9% institutional births. Home deliveries conducted by skilled health personnel — considered to be safe — are very low at 3.6%, putting the overall proportion of safe deliveries at 60.5% in Chamba. Home deliveries conducted by skilled health personnel remains very low in the state at 3.4%, linked directly to the health worker shortages.

Source: NFHS

The low proportion of immunisation in itself need not be a symptom of health system failure, as seen in the case of Hamirpur and Bilaspur districts who managed high levels of institutional births nevertheless. A priority of the next government must be to identify low uptake of immunisation in specific pockets and remedying it.

A priority of the next government must be to identify low uptake of immunisation in specific pockets and remedying it.

Standard indicators of undernutrition such as stunting, wasting and underweight have been improving in the state over the last decade. Surprisingly, Himachal has also emerged as one of the worst performing states in terms of management of anaemia among women of reproductive age. The state experienced a rise of more than 10 percentage points in anaemia in the last decade. Anaemia among pregnant women also showed a 12 percentage point increase. The total unmet need of family planning doubled in the state over the last decade. The proportion of women reporting current use of any modern method of family planning went down drastically from 72.6% in 2005-06 to 52.1% in 2016.

The proportion of men and women who are either overweight or obese has more than doubled in the state over the last decade. There is considerable increase in the proportion of working age men who report consumption of alcohol. From 29.5% in 2005-06, it has risen to a worrying 39.7% in 2016. Given the implications on the non-communicable disease burden, these aspects need increased policy focus.

Himachal’s health and nutrition challenges are compounded by severe human resource constraints in the public sector. The earlier gains of the state are at the risk of being wiped out, as demonstrated by the regression in immunisation and anaemia as well as the glacial improvements in child mortality. There is a need to identify districts — talukas if possible — which need enhanced focus in terms of health and nutrition interventions. In short, Himachal’s reputation as the rural health success story is under grave threat.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Oommen C. Kurian is Senior Fellow and Head of the Health Initiative at the Inclusive Growth and SDGs Programme, Observer Research Foundation. Trained in economics and ...

Read More +

Rakesh Kumar is a Associate Fellow at ORF. He has done PGDCA (Post Graduation Diploma in Computer Application) from CMC, Delhi Centre and CIC(certificate in ...

Read More +