-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

India needs to enhance its programme effectiveness and reach. It calls for proactive measures and scaling up of innovations required to address malnutrition.

The National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-5 data released last week for 22 states and Union territories indicates a worrying rise in malnutrition in India between 2016 and 2019. This is a double blow, reversing progress made towards meeting the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of ending hunger, and making efforts for achieving food security and improved nutrition due to the pandemic even harder.

The Sustainable Development Goals Index 2019-20 shows India’s sluggish performance on SDG 2 (Zero Hunger by 2030). India’s composite score on SDG 2 was the lowest amongst all the SDGs, indicating the need for robust policies and initiatives to end hunger in the country. India ranks 94 out of 107 countries in the 2020 Global Hunger Index, with 14 percent of the population being undernourished. Chronic undernutrition results in stunting, which has lifelong consequences on human capital, poverty and equity. It leads to less potential in education and, consequently, fewer professional opportunities, and continues to be a big challenge for Indian children. India is ranked at the 116th position of the 174 countries in the Human Capital Index 2020.

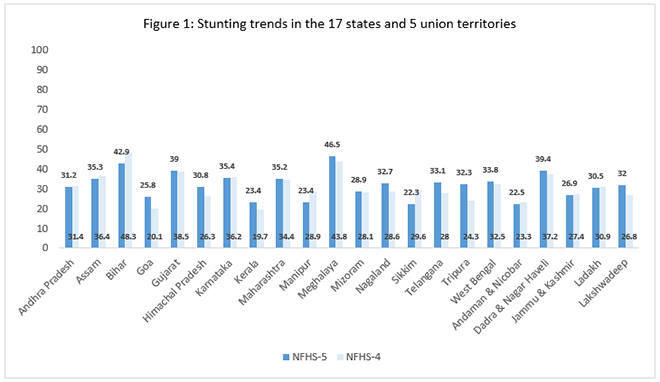

While health service indicators — such as under five and infant mortality rates — show improvement, the NFHS-5 indicates worsening of the nutritional status of children under the age of five in many of the states and union territories. The situation further aggravates with inadequate infant and young child feeding practices. Figure 1 indicates the stunting trends for 17 states and five union territories.

Of the 17 states, 11 showed a rise in stunting, including some of the populous states like Maharashtra, West Bengal, Gujarat, and Kerala, to name a few. The highest stunting is observed in Meghalaya (46.5%), and Bihar (42.9%); the Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey 2016-2018 had shown high rates of stunting for Bihar and Meghalaya at 42 and 40.4 percent respectively. On the other hand, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (22.5%) and Sikkim (22.3%) observed the lowest rate of stunting. The most significant decline can be observed in Sikkim (a 7.3 percentage point drop) since NFHS-4. The least progress can be seen in Ladakh and Andhra Pradesh. Bihar has shown improvement from 48.3 percent in 2015-16 to 42.9 percent in 2019-20; however, Bihar still shows high levels of stunting in children under the age of five. It is also alarming to see a rise in the percentage of those with stunted growth in Kerala and Goa by almost 4 and 5 percentage points respectively since the last survey. The NFHS-5 shows a sharp rise in stunting for Kerala, Goa and Tripura, which is a cause for concern.

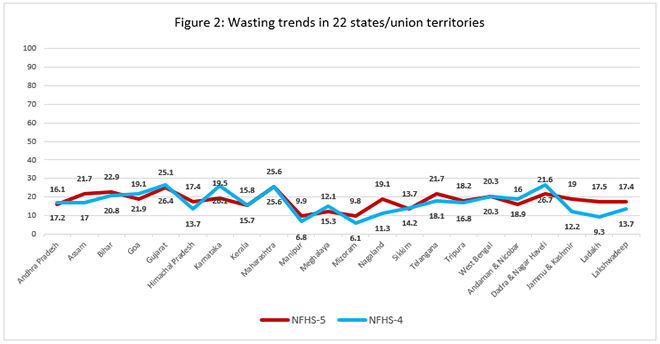

Wasting, as is indicative from figure-2, has not declined — it has either risen or remained stagnant in most of the states/union territories. The States of Assam, Bihar, Himachal, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Telangana, Tripura, and the union territories of Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh and Lakshwadeep have shown a 0.1 (Kerala) to 8.2 (Ladakh) percentage point increase in wasting in children under five. No change was observed in Maharashtra and West Bengal. A steep decline of 6.6 percentage points was observed in Karnataka. Wasting continues to be widespread, and multiple interventions have not managed to improve the situation over decades. India alone accounts for almost 50 percent (25.5 million) of the number of wasted children in the world (49.5 million).

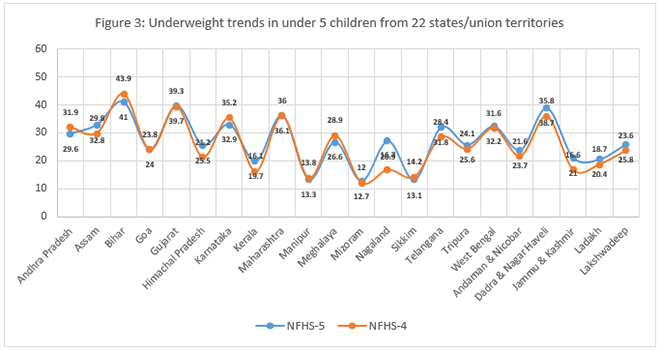

Data trends for the underweight population seem to be overlapping in most of the states/union territories (Figure-3). A marginal decline of 0.5 (Manipur) to a high of 2.9 (Bihar) percentage points has been observed. While efforts are being made, on-ground action is not good enough. Data indicates an increase in those who are underweight in the five union territories. Out of the total states, 11 have seen a rise in the population who are underweight.

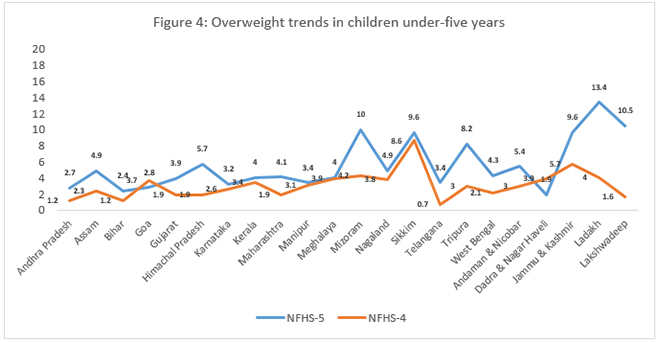

Figure 4 clearly shows an increasing trend in overweight prevalence in children under five. The double burden of malnutrition is a growing threat and immediate action is imperative. A steep incline in overweight children under five has been observed in the states of Himachal Pradesh and Mizoram, and the union territories of Ladakh and Lakshwadeep. Evidence shows that an excess intake of salt, sugar and lack of physical activity among children as the leading causes for the rising trend.

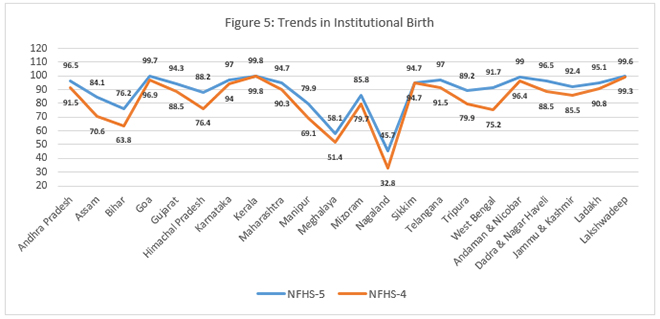

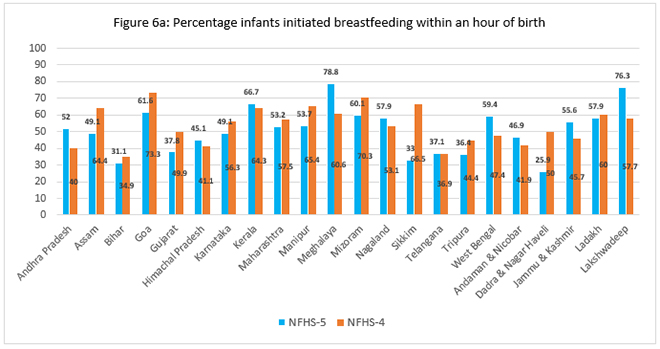

Evidence indicates a strong association between institutional delivery and early initiation of breastfeeding. However, the effect of increasing institutional delivery on rates of early initiation of breastfeeding is dependent on national and facility-based policy and the skill of health professionals. Going by the NFHS-5 data, there seems no effect of institutional births (Figure 5) on rates of early initiation of breastfeeding (Figure 6a). Alarming trends indicate a decline in early initiation of breastfeeding in 12 states/union territories. The maximum decline has been observed in Sikkim (33.5 percentage points), Dadra and Nagra Haveli (24.1 percentage points), and Assam (15.3 percentage points). Lakshwadeep has shown an 18.6 percentage point increase followed by Meghalaya and Andhra Pradesh showing an incline of 12 percentage point in rates of early initiation of breastfeeding.

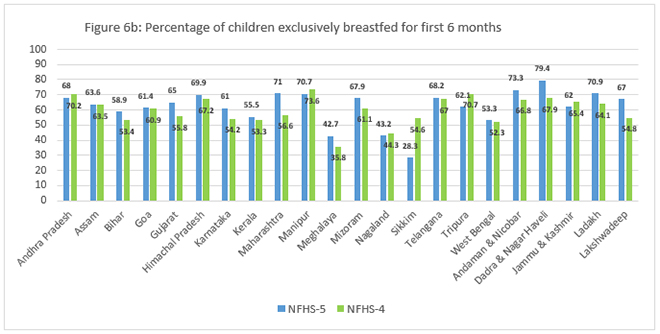

Figure 6b indicates the trends in exclusive breastfeeding. The rates are not promising with marginal improvement. Maharashtra indicates the highest incline of 14.4 percentage points followed by Lakshwadeep (12.2), Dadra and Nagra Haveli (11.5), and Gujarat (9.2). A steep decline of 26.3 percentage points has been observed in Sikkim.

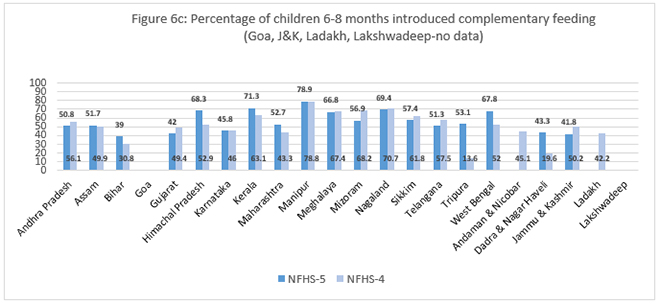

A similar trend is observed in the introduction of complementary feeding (Figure 6c), with nine states/union territories showing a decline in rates. There is wide variation in states with Tripura showing an increase of 39.5 percentage points and Himachal Pradesh a decline by 15.4 percentage points. However, data from the rest of the 17 states/union territories shows improvement in percentage of children below two years receiving an adequate diet. The highest was in Meghalaya with 29.8 percent children and lowest was in Gujarat with only 5.9 percent children being fed an adequate diet. India must improve in these areas as poor nutrition in the first 1,000 days of a child’s life can lead to stunted growth.

The POSHAN Abhiyaan, launched in 2017, strives to achieve SDG-2 of eliminating all forms of malnutrition by 2030 in children under five years. This seemed a tall ask given a one percent decadal decline in stunting, from 48 in 2006 to 38.4 in 2016. The current data shows disturbing trends of malnutrition, which pushes back the progress achieved so far.

The pandemic has added to the burden of families not being able to make ends meet due to loss of wages and looming poverty. India needs to enhance its programme effectiveness and reach. It calls for proactive measures and scaling up of innovations required to address malnutrition. We need to act now and strengthen actions on healthy diets; maternal, infant and young child nutrition; management of wasting; micronutrient supplementation; school feeding and nutrition; and nutrition surveillance. This picture looks gloomy, but efforts are being made, however, realisation of these efforts takes effective implementation and time. But it is doable.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr. Shoba Suri is a Senior Fellow with ORFs Health Initiative. Shoba is a nutritionist with experience in community and clinical research. She has worked on nutrition, ...

Read More +