-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

If community transmission can be mitigated or avoided altogether in the small population through extraordinary human-centred measures, the Seychelles may continue to report some of the lowest numbers of confirmed cases in the Indian Ocean.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted almost every country around the world, including small island African nations such as the Seychelles. As transmission rates vary from place to place, the management of this outbreak has been highly influenced by the response measures adopted by each country. At the time of writing, the Seychelles has confirmed an eighth imported case of the coronavirus and continues to see no evidence of community transmission. This is currently proving to be something of an anomaly in the region.

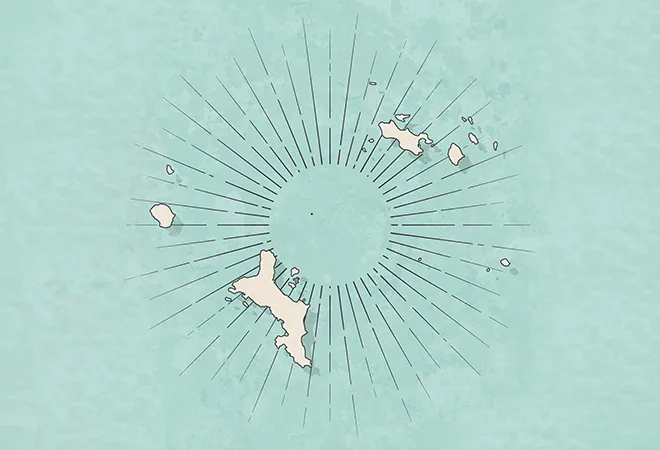

The smallest country to form part of Africa with a population roughly numbering 95,000, the Seychelles is reporting far fewer cases than other Indian Ocean islands, which may point to successful initial control measures. Its closest neighbours, namely Mauritius, Sri Lanka and the Maldives are presently confirming double and even triple digit figures of 102, 113 and 16 cases respectively. How have policymakers and public health officials responded to this crisis and can the rest of Africa stand to learn from it?

Located 4 degrees south of the Equator, the Seychelles archipelago is geographically distanced from much of the world but remains well-connected via technology. This means information — and information overload — about the coronavirus is very much a feature of this public health crisis on the islands as well. In a bid to stem the flow of false information, the Ministry of Health has opted for social media and daily press updates to keep members of the public informed about confirmed case numbers, testing results and the status of quarantined persons. Transparency and the continuous provision of information has thus proved pivotal in stemming fears and panic buying behaviours among the populace.

The Seychelles is no stranger to public health crises; the country weathered SARS and H1N1 with aplomb. However, the speed and nature of this virus’ spread makes it an unprecedented event for the island. As the number of confirmed cases mounted, the public health commissioner swiftly declared a public health emergency in mid-March. This allowed for an increase in resources directed towards battling the outbreak on the ground. Rigorous contact tracing and home quarantine measures were put into effect, with positive cases being isolated in the hospital quarantine unit. All learning centers, including the University of Seychelles, were shut down indefinitely. Travel advisories banned all Seychelles residents from travelling overseas for 30 days. Social distancing measures were also put in effect; a four-person limit on public gatherings has been imposed to further prevent the spread of the virus. With 90% of the population following the Roman Catholic faith, the Catholic Church has banned all religious services. The national airline Air Seychelles has suspended flights until April 2020. Most inbound flights have also ceased. For now, everyone is trapped in paradise.

COVID-19 will test an island nation that is already labouring under the burden of social ills. Government figures show nearly 5,000 people are heroin addicts, equivalent to almost 10% of the national workforce, which prompted the declaration of a public health emergency in 2017. Ironies further abound; the Seychelles is classed as the only high-income country on the African continent, but 40% of the population is reported to live in poverty. As other African nations are no doubt learning, the public health emergency posed by the coronavirus has served to strain the resources of an already overburdened public health system.

Which is where external aid efforts have been welcomed. Two separate donations of medical equipment from the UAE and Alibaba founder Jack Ma made their way into the country last week, providing much needed relief for public health officials.

Unlike Mauritius and Sri Lanka, the Seychelles has not declared a complete lockdown — yet. However, it is not business as usual, despite government assurances that salaries for the impacted workforce will be paid out. The country relies heavily on foreign labour; about 25% of the workforce is made up of migrant workers primarily in the tourism and construction sectors. In the latter sector, workers from India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka are asked to remain in their quarters after working hours. Most businesses, especially those in the tourism industry, have suspended operations and requested workers to take unpaid leave.

With tourism being the biggest income and foreign exchange earner for the country, national concerns lie between balancing the public health needs versus the economic fragility of the country. Given that Seychelles imports almost 90% of its consumption products, the outbreak may very well hinder trade, consumer spending and business revenue. The fall in visitor arrivals has seen empty beaches, ferries and hotels, leading to fears of unemployment and economic downturn. A staggering 2,300 tourist bookings worth USD 3.8 million were cancelled between February and March alone as the virus cratered demand for travel. The country is already projecting a 64% drop in tourist arrivals for the year. Mauritius appears to be in the same boat; their forecasted growth rate of 4.2% in 2020 has been revised down to 3.7%. COVID-19 may thus force small island nations to seek alternatives to tourism in order to earn revenue.

For now, the government is prioritising health above wealth. The public health officials and health workers everywhere should be commended for their tireless efforts around surveillance, monitoring, contact tracing and testing of suspected cases. The island nation may very well be exhibiting a case of ‘small is beautiful’; if community transmission can be mitigated or avoided altogether in the small population through extraordinary human-centred measures, the Seychelles may continue to report some of the lowest numbers of confirmed cases in the Indian Ocean. For now, the country will need to continue focusing its scarce resources on dealing with the current situation and mitigating the impact of the outbreak on the population.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Malshini Senaratne is a lecturer at the University of Seychelles and a Director with Eco-Sol Consulting Seychelles. Her research interests include entrepreneurship Blue Economy ecosystem ...

Read More +