Over the past few years, the fallout of West Asian geopolitics has often played on the high seas, with tensions between the Gulf and Israel on one side and Iran on the other playing out in the Persian Gulf, the Gulf of Oman, and most notably the

Strait of Hormuz — a critical narrow body of water between Iran and the Arab Gulf. As of 2018, more than

20 million barrels of oil travelled through the Strait of Hormuz each day, arguably making it one of the most critical chokepoints for global oil and gas supplies. The alternative route, developed around the Red Sea, is now also developing as a major point of inflection.

Tensions between Iran and the Gulf have always been the nucleus of security concerns in the region. However, after Iran signed the nuclear deal with the P5+1 and the unceremonious withdrawal of the agreement by the United States (US) under President Donald Trump in 2018, covert wars between Israel and Iran and US and Iran, largely taking place on land and in the air,

shifted to the high seas of the Persian Gulf and its surrounding waters, targeting critical oil trade lines. The Persian Gulf over the past months has seen clandestine attacks on merchant ships operating at the ports in the Gulf to Iranian gunboats harassing ships belonging to the US military,

mysterious explosions on Israeli flagged ships, and equally mysteriously

Iranian naval ships catching fire and later sinking in the Gulf of Oman.

The idea to circumvent the Strait of Hormuz chokepoint using the Red Sea by the likes of Saudi Arabia is not new.

In view of these developments, Asian economies, which today are the largest importers of hydrocarbons from West Asia, became much more militarily astute in the region. The Indian Navy in 2019 began Operation Sankalp, providing protection and escort to crude oil carriers to safely pass the Strait of Hormuz towards India, a country that imports more than 80 percent of its oil supplies. According to several

reports, Indian Navy war ships escorted 16 Indian-flagged merchant vessels per day in the Gulf as part of Operation Sankalp.

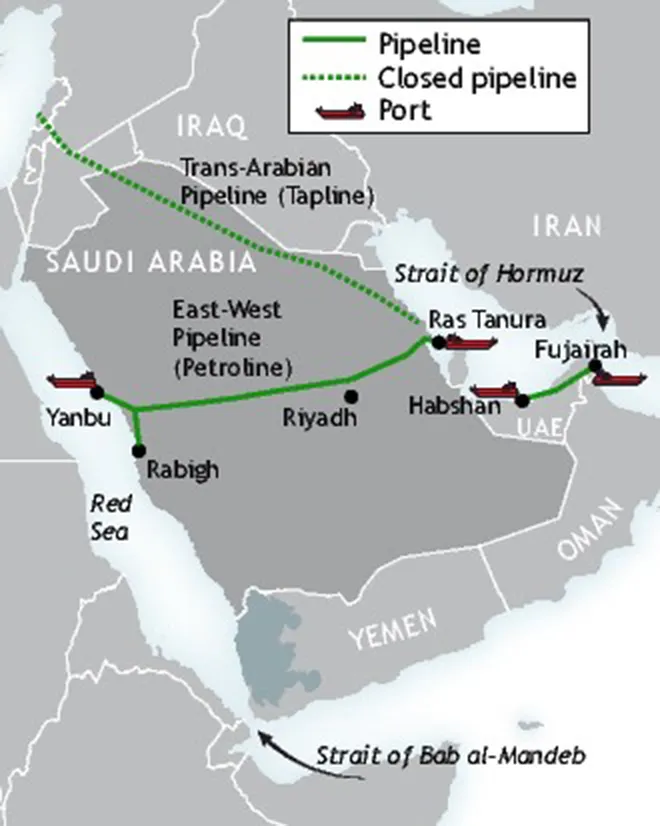

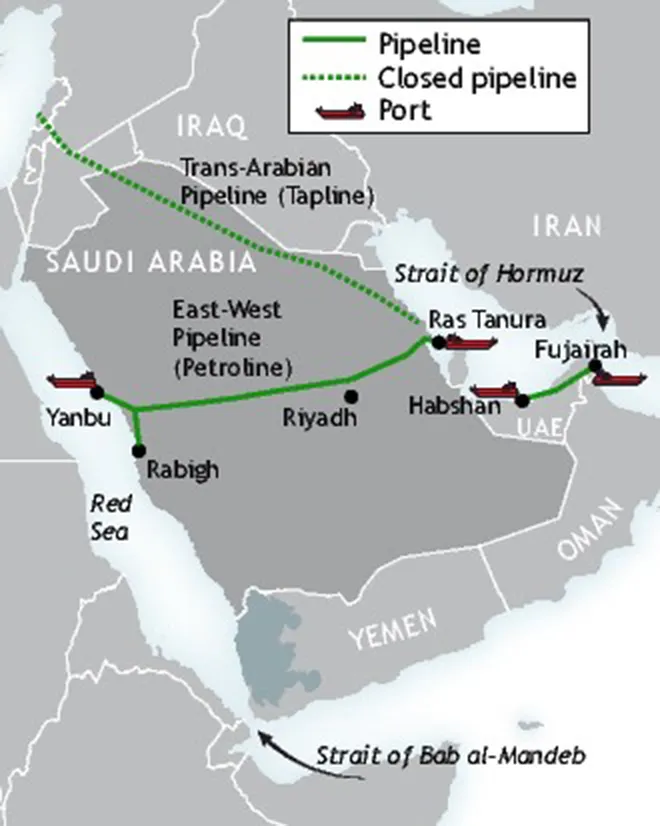

The idea to circumvent the Strait of Hormuz chokepoint using the Red Sea by the likes of Saudi Arabia is not new. In light of geopolitical tremors in Persian Gulf, the Saudis are expanding the capacity of their East-West Oil Pipeline (EWOP) which will take crude from major oilfields such as Abqaiq to the ports of Yanbu and Rabigh, on the Red Sea, in an effort to bypass maritime hostilities and Iranian threats around the Strait of Hormuz. However, this is easier said than done today, as the Red Sea itself has seen rapid militarisation over the past couple of years.

Source: Argus

Source: Argus

The Red Sea is not devoid of regional and international geopolitical roadblocks. If the Strait of Hormuz was captive to Iran’s proximity and threat, the Yemen war and Tehran’s backing of the Houthi rebels in the conflict make the Red Sea open to the very same geographic and geopolitical threats as the Persian Gulf. The Houthis have already been blamed for attacking Saudi interests and infrastructure in and around the Red Sea using drones and IEDs, showcasing Iran’s capability to challenge the Arab states and Israel beyond just its periphery. Further, the small nation of Djibouti on the African side of the Red Sea is

home to military presence of the US, China, Japan, Italy, and France. Meanwhile, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has multiple military anchors on this edge of West Asia, with bases in Somalia and an upcoming military installation with a fully operational airport on Mayun Island — a barren piece of land placed in between Yemen and Djibouti — in the centre of the Bab al-Manbab Strait, which in its geographical design is a similar chokepoint for the Red Sea what Strait of Hormuz is to the Persian Gulf. The

Mayun Island base would give the UAE tremendous reach around the Red Sea, arguably give access to the Saudis by association if required, and also place themselves with close Western allies such as the US and even China.

The Red Sea is not devoid of regional and international geopolitical roadblocks.

Beyond the above-mentioned states, Russia was also under negotiations with Sudan to setup a military base on the Red Sea. The deal, as per

information released in 2020, was to give Russia’s navy access to Port Sudan via a 25-year lease agreement. However, as per

reports in June 2021, Khartoum was going to review the deal with Moscow to make sure such a deal was going to serve the country’s interests. This comes on the back of Sudan joining the Abraham Accords in January 2021 that normalised relations between the Arab states and Israel, pushed through with the help of the US. In return, Sudan, which in the 1990s was home to Osama Bin Laden, also achieved a significant victory that of being

removed from the US terrorism list. The pushback on the Russian base deal by Sudan could be seen through the lens of the Accords, and the UAE and US potentially pressurising Khartoum to step back on Moscow’s access to Port Sudan.

India’s naval presence in the region may become a long-term fixture, with it becoming one of the world’s top crude importers, having increased diplomatic presence and heft in West Asia and potential

access to facilities such as Duqm Port in Oman, a neutral country that helps New Delhi balance a potential military outpost between its diplomatic interests in the Gulf and Iran.

India’s Operation Sankalp may in the future transition into a more institutionalised presence in the region, with the ability for long-term docking at bases and expanding the scope of military cooperation with friendly states.

While major oil producers such as Saudi see the Red Sea as means to circumvent the Strait of Hormuz conundrum, the pace at which military developments are taking place around the Red Sea will add more miles for the Indian Navy to worry about, stretch its capacity in the Arabian Sea, and the extended Indian Ocean, and demand further diplomatic and kinetic resources underlined by the need to protect Indian energy security requirements back home. India’s Operation Sankalp may in the future transition into a more institutionalised presence in the region, with the ability for long-term docking at bases and expanding the scope of military cooperation with friendly states.

New Delhi’s participation in the

military exercise Cutlass Express 2021, organised by the US along the eastern African coastline, with others such as the UK, Djibouti, Sudan, Somalia, Seychelles, and so on taking part, showcases an increasing merge between India’s approach to the Arabian Sea, Indian Ocean, and the developing Indo-Pacific narrative. Asian states, particularly Asian economies importing oil as primary customers today, will see a demand for a significant increase in their military footprint in and around the waters of West Asia. India should realistically design and prepare for such a kinetic and political capacity increase over the next few years.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Over the past few years, the fallout of West Asian geopolitics has often played on the high seas, with tensions between the Gulf and Israel on one side and Iran on the other playing out in the Persian Gulf, the Gulf of Oman, and most notably the

Over the past few years, the fallout of West Asian geopolitics has often played on the high seas, with tensions between the Gulf and Israel on one side and Iran on the other playing out in the Persian Gulf, the Gulf of Oman, and most notably the

PREV

PREV